Abstract

Objective:

The first year of college is an important transitional period for young adults; it is also a period associated with elevated risk of incapacitated rape (IR) for female students. The goal of this study was to identify prospective risk factors associated with experiencing attempted or completed IR during the first year of college.

Method:

Using a prospective cohort design, we recruited 483 incoming first-year female students. Participants completed a baseline survey and three follow-up surveys over the next year. At baseline, we assessed precollege alcohol use, marijuana use, sexual behavior, and, for the subset of sexually experienced participants, sex-related alcohol expectancies. At the baseline and all follow-ups, we assessed sexual victimization.

Results:

Approximately 1 in 6 women (18%) reported IR before entering college, and 15% reported IR during their first year of college. In bivariate analyses, precollege IR history, precollege heavy episodic drinking, number of precollege sexual partners, and sex-related alcohol expectancies (enhancement and disinhibition) predicted first-year IR. In multivariate analyses with the entire sample, only precollege IR (odds ratio = 4.98, p < .001) remained a significant predictor. However, among the subset of sexually experienced participants, both enhancement expectancies and precollege IR predicted IR during the study year.

Conclusions:

IR during the first year of college is independently associated with a history of IR and with expectancies about alcohol’s enhancement of sexual experience. Alcohol expectancies are a modifiable risk factor that may be a promising target for prevention efforts.

Sexual assault on college campuses is increasingly recognized as a major social and health problem (White House Council on Women and Girls, 2014). Sexual assault refers to any unconsented sexual contact, ranging in severity from kissing and touching to intercourse (Krebs et al., 2007). Estimates suggest that one in five women will experience some form of sexual assault during her college years (Krebs et al., 2009). An extreme form of sexual assault is rape, defined as unwanted completed or attempted sexual penetration. Incapacitated rape (IR) refers to completed or attempted penetration that occurs while a victim is incapacitated because of consumption of alcohol or other drugs. Cross-sectional studies indicate that IR is more prevalent than forcible rape (i.e., involving the threat or actual use of physical force) in college samples (Krebs et al., 2009; Lawyer et al., 2010; Mohler-Kuo et al., 2004).

Sexual assault can lead to physical injury, sexually transmitted infections, and unplanned pregnancy as well as anxiety, depression, and other mental health problems (Choudhary et al., 2008). Sexual assaults that follow alcohol use (e.g., IR) are associated with significant emotional distress (Brown et al., 2009) and can lead female victims to blame themselves and to feel stigmatized by peers (Littleton et al., 2009).

Given the prevalence and impact of IR in the context of college, its prevention must become a high priority. Accumulating data suggest that the risk of IR is highest in the first year of college (Krebs et al., 2009; White & Smith, 2004) and may peak in the early months of the first semester (Kimble et al., 2008). Although comprehensive sexual assault prevention must address the behavior of perpetrators and engage peer bystanders in actively changing campus norms, continued development of prevention programs for women is also needed (Gidycz et al., 2011b; Senn et al., 2015). Therefore, to optimize the efficacy of early prevention programming for college students, it is essential to determine if precollege factors that increase the risk of experiencing IR can be identified.

Most prior research has studied predictors of sexual assault broadly, rather than IR in particular, and sampled adult women in general or female students across all years of college. Nonetheless, existing research on sexual assault suggests five potential predictors of IR.

Prior sexual victimization is strongly related to the risk of future victimization. Women raped as minors were twice as likely to be raped again as adults when compared with women who had no such history (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). One study indicated that 35% of women raped before age 18 experienced a subsequent rape as an adult, compared with 14% of those with no rape history (Black et al., 2011). The more recent and severe a sexual assault, the more it increases revictimization risk; thus, adolescent sexual assault carries a greater risk for revictimization than does childhood sexual assault (Classen et al., 2005). Female college students with a history of incapacitated sexual assault are at substantially higher risk of being revictimized than women without such a history (Messman-Moore et al., 2013b). Therefore, we expect that precollege IR will increase risk for IR during the first year of college.

Alcohol use has been consistently linked to risk of sexual assault (Abbey, 2002; Testa & Livingston, 2009). The pattern referred to as heavy episodic drinking appears to be the most relevant risk factor for IR among college students. For women, a heavy drinking episode is defined as consuming four or more drinks within 2 hours (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2004). Among female students graduating from high school, heavy episodic drinking was associated with experiencing IR as an adolescent: 5% of light drinkers, 21% of occasional heavy drinkers, and 36% of monthly heavy drinkers had a history of IR (Testa & Hoffman, 2012). As freshmen in college, women’s risk of IR during the semester increased with the maximum number of drinks consumed on a single occasion during the same period (Testa & Hoffman, 2012). Alcohol use predicts IR, but not forcible rape, in both community-dwelling women (Testa et al., 2003) and residential college students (McCauley et al., 2009). Thus, consistent with our aim to identify prospective predictors, we predict that engaging in heavy episodic drinking episodes before starting college will increase subsequent risk for IR during the first year of college.

Marijuana use has been associated with increased risk of sexual assault. In one study, 50% of college rape victims used marijuana, compared with 24% of college women overall (Messman-Moore et al., 2008). In two studies examining urine samples collected at hospitals and rape crisis centers, one in five samples contained marijuana (ElSohly & Salamone, 1999; Slaughter, 2000). Krebs and colleagues (2007) reported that 65% of IR victims used marijuana, compared with 39% of forcible rape victims and 30% of nonvictims. These data suggest that marijuana use may be more strongly associated with IR than with other forms of sexual assault. Therefore, precollege marijuana use may be an additional prospective predictor of IR.

The number of lifetime sexual partners has been associated with sexual assault risk (Abbey et al., 2004; Benson et al., 2007; Messman-Moore et al., 2013a). A recent crosssectional study of college women found that increased number of consensual sexual partners increased the risk for IR, forcible rape, and verbally coerced assaults (Franklin, 2010). Prospective research also supports the association between number of partners and risk of sexual victimization (Testa et al., 2007). Because having had more sexual partners in the past predicts having more partners in the future, which may increase a woman’s chances of encountering a risky situation or potential perpetrator, we predict that more precollege sexual partners will increase subsequent risk for IR in the first year of college.

Sexual assault victims generally hold stronger positive alcohol expectancies regarding social enhancement and sexual activity than nonvictims (Benson et al., 2007; Corbin et al., 2001). Limited research suggests that victims of alcohol-involved sexual assaults hold stronger positive alcohol expectancies than either nonvictims or victims of assaults that do not involve alcohol (Bedard-Gilligan et al., 2011; Marx et al., 2000). More positive alcohol–sex expectancies may lead to more drinking in situations likely to lead to sexual activity (Messman-Moore et al., 2013a). Thus, we predict that women endorsing stronger sex-related alcohol expectancies may be at higher risk of experiencing IR during the first year of college than women with weaker expectancies.

In summary, research strongly suggests that behavioral and cognitive factors that predate the start of college may increase risk of IR. However, most prior research has addressed sexual assault in general, not IR specifically, and has not used a prospective design to measure prevalence during the first year of college. The purpose of this study was to identify prospective predictors of IR experienced during the first year of college to inform targeted and tailored prevention programs in the first year. Based on prior research, we hypothesized that IR would be more likely among those women with pre-college histories of (a) IR, (b) heavy episodic drinking, (c) marijuana use, and (d) more sexual partners. We also hypothesized that (e) women holding stronger sex-related alcohol expectancies at baseline would be at higher risk of experiencing IR.

Method

Participants

Participants were 483 first-year female undergraduates at a private university in the Northeast who were participating in a larger study of health behaviors and relationships specific to first-year women, called the Women’s Health Project (Fielder et al., 2014). Our participants consisted of 26% of the incoming female class. At baseline, 94% of participants were 18 years old (range: 18–21); 69% identified as White, 11% as Asian, 8% as Black, 13% as other or multiple races, and 8% as Hispanic; 36% were in a committed relationship, and 96% reported their sexual orientation as heterosexual. Participants did not differ from the larger student body on racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variables (see Fielder et al., 2014).

Measures

Demographics.

Participants provided information about their age, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation at baseline. They indicated their relationship status (single or in a committed relationship) at every assessment.

Sexual victimization.

At baseline and every 4 months thereafter, participants completed a set of items based on the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss et al., 2007) and adapted by Testa to use tactics as item stems and include the tactic of incapacitation (Testa et al., 2010a). The 20-item measure crossed four perpetrator tactics with five types of sexual contact and asked participants to report the number of times (0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4) each type of event had happened since age 14 (at baseline), since the start of school (end of first semester), since January 1st (end of second semester), and since May 1st (end of summer). The four perpetrator tactics were “overwhelm you with arguments about sex or continual pressure for sex,” “use physical force,” “threaten to harm you or someone close to you,” and “perform sexual acts while you were incapacitated by drugs or alcohol and unable to object or consent.” The five types of sexual contact were “fondle, kiss, or touch sexually,” “oral sex,” “try to have sexual intercourse, but it did not happen,” “succeed in making you have sexual intercourse,” and “anal sex or penetration with a finger or objects.”

We defined IR as any of the four penetrative acts (oral sex, attempted intercourse, completed intercourse, or anal sex) that occurred because of the perpetrator tactic of victim incapacitation. Participants were considered to have experienced IR during the study year if they met these criteria at one or more assessment occasions (first semester, second semester, summer).

Alcohol use.

At the baseline assessment, participants reported the number of heavy drinking episodes they had engaged in during the previous month. A heavy drinking episode was defined using a gender-specific measure of four or more drinks on one occasion, and a standard drink was defined as 12 oz. of beer, 5 oz. of wine, or a shot of distilled spirits. A dichotomous variable was created representing heavy drinking (yes/no) in the last month.

Marijuana use.

At baseline, participants reported the number of days in the last month they had used marijuana. A dichotomous variable was created representing marijuana use (yes/no) in the last month.

Number of sexual partners.

At baseline, participants indicated the number of romantic and casual partners with whom they had vaginal sex in their lifetime. A summary score representing total number of precollege vaginal sex partners was used.

Sex-related alcohol expectancies.

For participants who reported at least one oral or vaginal sex partner, we assessed sex-related alcohol expectancies at baseline. Three 3-item subscales derived from Dermen and Cooper’s 12-item scale (Dermen & Cooper, 1994) measured (a) enhancement, (b) sexual risk taking, and (c) disinhibition. Participants rated their agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Procedure

The university’s institutional review board approved all research procedures. Participants were recruited through a mass mailing sent in August to matriculating first-year female students, as well as through campus flyers, word of mouth, and a department research pool during the first few weeks of the semester, which started August 30. Interested students attended an orientation meeting, after which they provided written informed consent and completed the first survey (Time [T] 1) that covered behavior in the month of August. Subsequently, participants completed 12 monthly online surveys (T2–T13) in the first week of each month about the events of the previous month. Data for the current study come from the surveys administered at baseline (T1), January/end of first semester (T5), May/end of second semester (T9), and September/end of summer (T13). Response rates for the T5, T9, and T13 assessments were 91%, 85%, and 88%, respectively. Participants received $10–$20 for each completed survey.

Data analysis

Nonresponses on the sexual assault items were assumed to be a negative response; available responses across T5, T9, and T13 contributed to estimates of incidence of IR across the study year. Hypothesized predictors were described, and outcomes were tested using chi-square analyses and t tests. Bivariate associations between predictors and study year IR were tested using logistic regression. Variables identified as significant predictors in bivariate models were included in multivariable logistic regression models.

Results

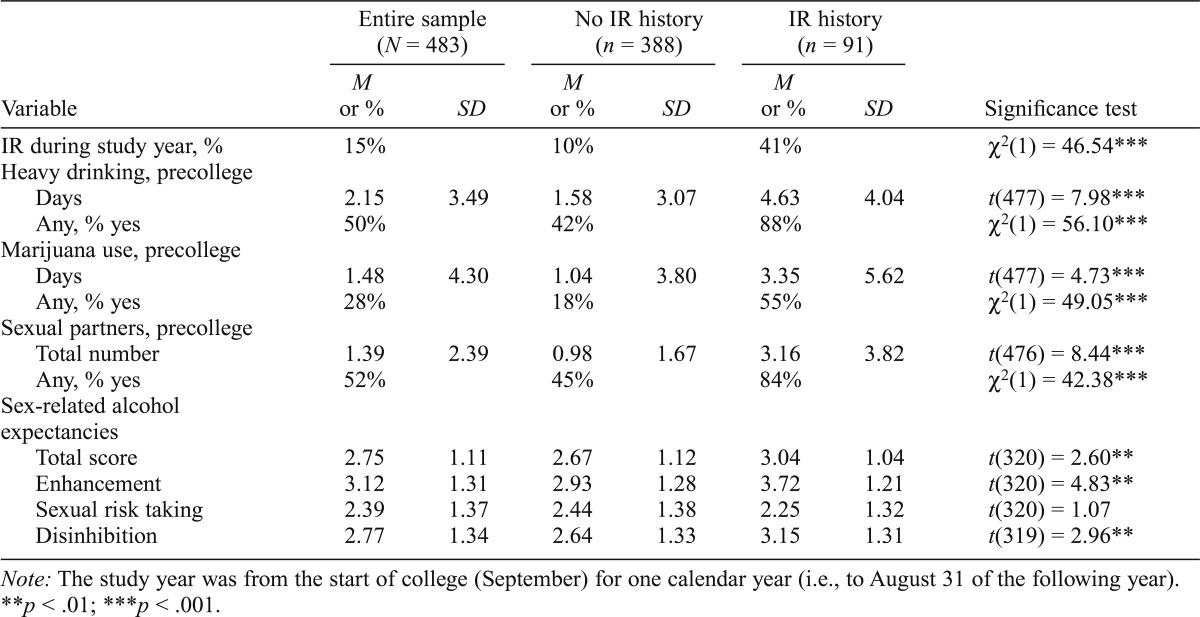

At the start of college, 17.5% of participants reported experiencing IR since age 14. Over the course of the first year of college, 15.4% reported IR. By the end of the study year, 25.7% had experienced lifetime IR. Because history of IR was significantly associated with most of the other predictor variables, Table 1 displays baseline values for all predictors for the whole sample and separately by IR history.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for incapacitated rape (IR) and its predictors for the entire sample and separately among participants with and without a history of IR

| Entire sample (N = 483) |

No IR history (n = 388) |

IR history (n = 91) |

|||||

| Variable | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | Significance test |

| IR during study year, % | 15% | 10% | 41% | χ2(1) = 46.54*** | |||

| Heavy drinking, precollege | |||||||

| Days | 2.15 | 3.49 | 1.58 | 3.07 | 4.63 | 4.04 | t(477) = 7.98*** |

| Any, % yes | 50% | 42% | 88% | χ2(1) = 56.10*** | |||

| Marijuana use, precollege | |||||||

| Days | 1.48 | 4.30 | 1.04 | 3.80 | 3.35 | 5.62 | t(477) = 4.73*** |

| Any, % yes | 28% | 18% | 55% | χ2(1) = 49.05*** | |||

| Sexual partners, precollege | |||||||

| Total number | 1.39 | 2.39 | 0.98 | 1.67 | 3.16 | 3.82 | t(476) = 8.44*** |

| Any, % yes | 52% | 45% | 84% | χ2(1) = 42.38*** | |||

| Sex-related alcohol expectancies | |||||||

| Total score | 2.75 | 1.11 | 2.67 | 1.12 | 3.04 | 1.04 | t(320) = 2.60** |

| Enhancement | 3.12 | 1.31 | 2.93 | 1.28 | 3.72 | 1.21 | t(320) = 4.83** |

| Sexual risk taking | 2.39 | 1.37 | 2.44 | 1.38 | 2.25 | 1.32 | t(320) = 1.07 |

| Disinhibition | 2.77 | 1.34 | 2.64 | 1.33 | 3.15 | 1.31 | t(319) = 2.96** |

Note: The study year was from the start of college (September) for one calendar year (i.e., to August 31 of the following year).

p < .01;

p < .001.

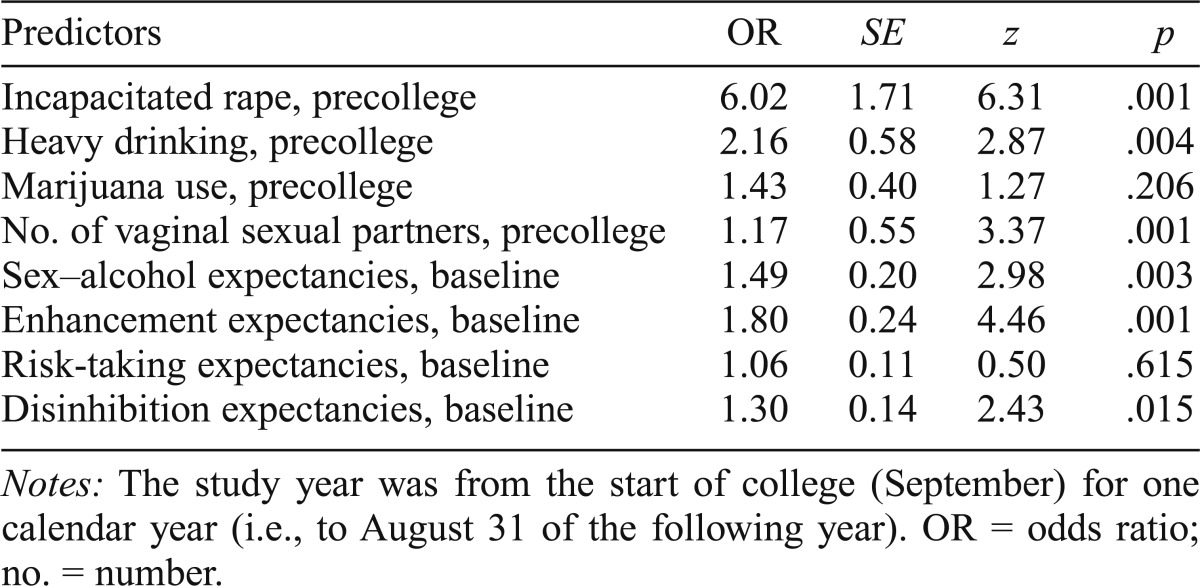

Predictors of incapacitated rape: Bivariate analyses

Table 2 displays the results of bivariate regression analyses between the hypothesized predictors and IR during the first year of college.

Table 2.

Predictors of incapacitated rape during the study year (bivariate relationships)

| Predictors | OR | SE | z | p |

| Incapacitated rape, precollege | 6.02 | 1.71 | 6.31 | .001 |

| Heavy drinking, precollege | 2.16 | 0.58 | 2.87 | .004 |

| Marijuana use, precollege | 1.43 | 0.40 | 1.27 | .206 |

| No. of vaginal sexual partners, precollege | 1.17 | 0.55 | 3.37 | .001 |

| Sex-alcohol expectancies, baseline | 1.49 | 0.20 | 2.98 | .003 |

| Enhancement expectancies, baseline | 1.80 | 0.24 | 4.46 | .001 |

| Risk-taking expectancies, baseline | 1.06 | 0.11 | 0.50 | .615 |

| Disinhibition expectancies, baseline | 1.30 | 0.14 | 2.43 | .015 |

Notes: The study year was from the start of college (September) for one calendar year (i.e., to August 31 of the following year). OR = odds ratio; no. = number.

Precollege history.

Revictimization was common. Among women who entered college with a precollege history of IR, 41% experienced IR again during the study year; in comparison, only 10% of women reporting no precollege IR experienced IR. History of IR increased the odds of IR in the year after starting college six-fold.

Alcohol use.

During the baseline month of August, 66% of participants reported drinking alcohol, and 50% reported an episode of heavy drinking. The dichotomized variable of any heavy drinking was used in logistic regression analyses. As shown in Table 2, the odds of experiencing IR during the study year more than doubled if a participant engaged in heavy episodic drinking in the month before starting college.

Marijuana use.

At baseline, 28% of participants reported using marijuana during the previous month. In bivariate analyses, marijuana use during the month before starting college did not predict IR risk during the study year.

Number of sexual partners.

At baseline, 52% of participants reported ever having had a vaginal sex partner. The number of precollege vaginal sexual partners was a significant predictor of IR during the study year.

Sex-related alcohol expectancies.

Among the 325 participants who reported at least one oral or vaginal sexual partner at baseline and completed the expectancy measure, the mean composite expectancy score was 2.75 (SD = 1.11; higher scores indicate stronger held expectancies). Participants who had experienced precollege IR held significantly stronger sex-related alcohol expectancies at baseline (M = 3.04) than those who did not (M = 2.67; Table 1). Considering the individual scales, this pattern held for expectancies for enhancement (M = 3.72 vs. 2.93) and disinhibition (M = 3.15 vs. 2.64) but not for sexual risk taking (M = 2.25 vs. 2.44). As shown in Table 2, bivariate logistic regression found an association between positive expectancies and IR risk. Specifically, higher enhancement and disinhibition expectancies at baseline significantly increased the odds of IR during the study year.

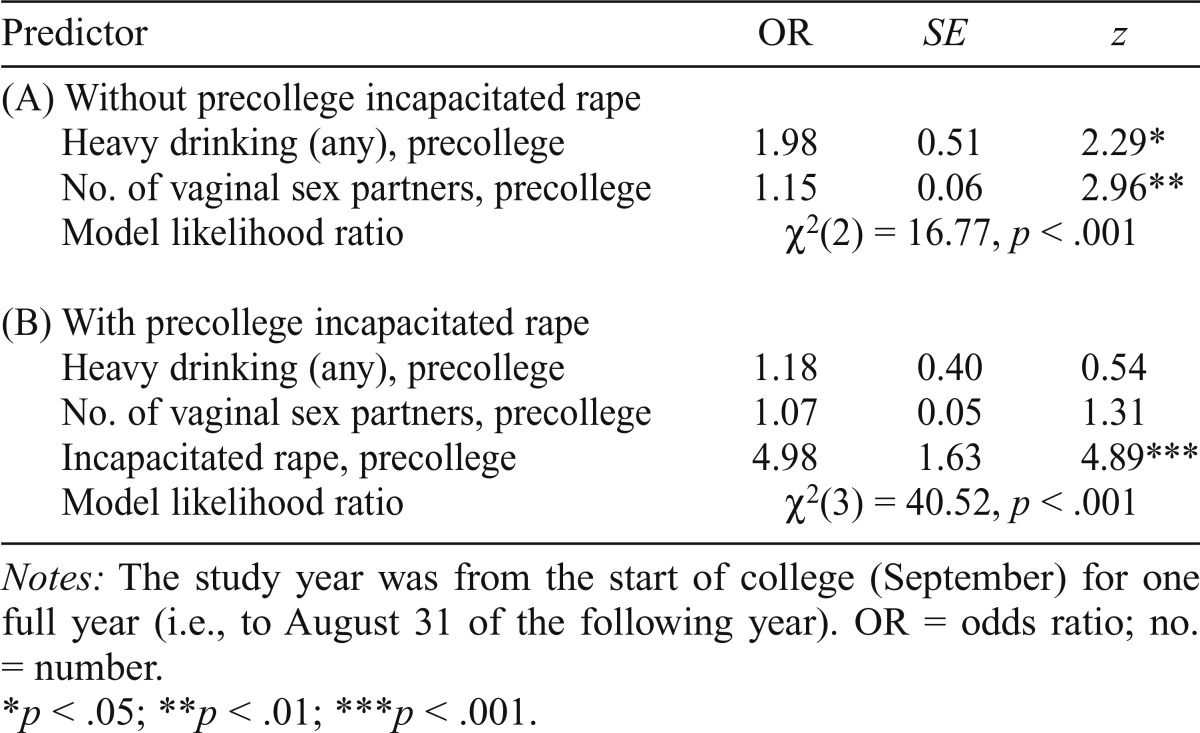

Predictors of incapacitated rape: Multivariate analyses

The significant bivariate predictors were entered into multivariate logistic regression models to predict study year IR. Because precollege IR was expected to remain a strong predictor of subsequent IR, multivariate models were conducted first without and then with precollege IR in order to more thoroughly examine the relative strength of other predictors. Because the sex-related alcohol expectancy questions were asked only of the subset of participants who reported prior sexual experience at baseline, regression models were run both without expectancies (full sample) and with expectancies (reduced sample).

Both baseline heavy drinking and precollege sexual partners predicted study year IR in a two-predictor model (Table 3, Section A). When precollege IR was added to this model (Table 3, Section B), precollege IR emerged as the only significant predictor of IR (OR = 4.89, p < .001).

Table 3.

Multivariate models predicting incapacitated rape during the study year (full sample)

| Predictor | OR | SE | z |

| (A) Without precollege incapacitated rape | |||

| Heavy drinking (any), precollege | 1.98 | 0.51 | 2.29* |

| No. of vaginal sex partners, precollege | 1.15 | 0.06 | 2.96** |

| Model likelihood ratio | χ2(2) = 16.77, p < .001 | ||

| (B) With precollege incapacitated rape | |||

| Heavy drinking (any), precollege | 1.18 | 0.40 | 0.54 |

| No. of vaginal sex partners, precollege | 1.07 | 0.05 | 1.31 |

| Incapacitated rape, precollege | 4.98 | 1.63 | 4.89*** |

| Model likelihood ratio | χ2(3) = 40.52, p < .001 | ||

Notes: The study year was from the start of college (September) for one full year (i.e., to August 31 of the following year). OR = odds ratio; no. = number.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

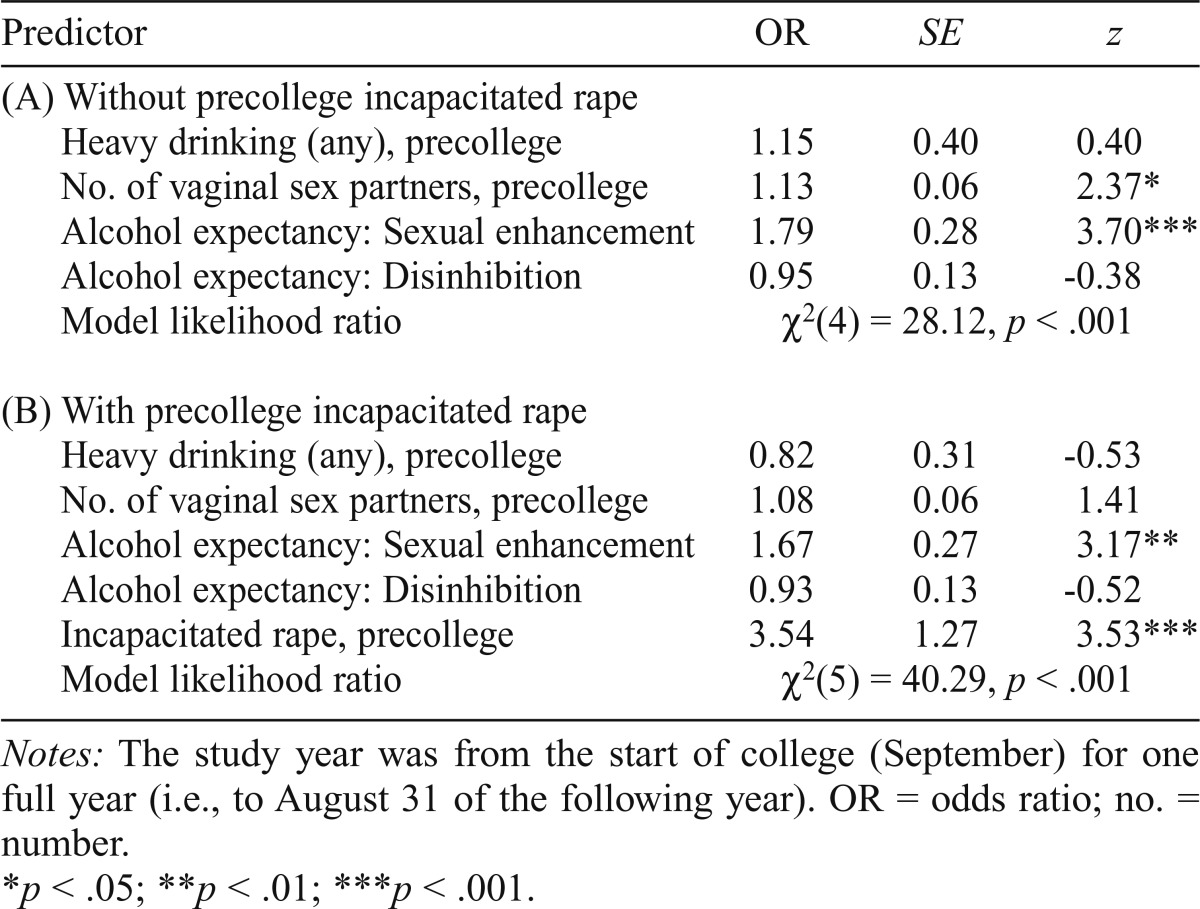

To explore the multivariate role of sex-related alcohol expectancies, we built a model with the reduced sample of 325 participants who had completed the expectancy measure. When expectancies were added to the initial two-predictor model, precollege sex partners and sexual enhancement expectancies remained significant predictors of IR (Table 4, Section A). When precollege IR was introduced into this four-predictor model (Table 4, Section B), sexual enhancement expectancies (OR = 1.67) and precollege IR (OR = 3.54) remained significant predictors.

Table 4.

Multivariable models predicting incapacitated rape during the study year, including sex-related alcohol expectancies (reduced sample, n = 325)

| Predictor | OR | SE | z |

| (A) Without precollege incapacitated rape | |||

| Heavy drinking (any), precollege | 1.15 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| No. of vaginal sex partners, precollege | 1.13 | 0.06 | 2.37* |

| Alcohol expectancy: Sexual enhancement | 1.79 | 0.28 | 3.70*** |

| Alcohol expectancy: Disinhibition | 0.95 | 0.13 | -0.38 |

| Model likelihood ratio | χ2(4) = 28.12, p < .001 | ||

| (B) With precollege incapacitated rape | |||

| Heavy drinking (any), precollege | 0.82 | 0.31 | -0.53 |

| No. of vaginal sex partners, precollege | 1.08 | 0.06 | 1.41 |

| Alcohol expectancy: Sexual enhancement | 1.67 | 0.27 | 3.17** |

| Alcohol expectancy: Disinhibition | 0.93 | 0.13 | -0.52 |

| Incapacitated rape, precollege | 3.54 | 1.27 | 3.53*** |

| Model likelihood ratio | χ2(5) = 40.29, p < .001 | ||

Notes: The study year was from the start of college (September) for one full year (i.e., to August 31 of the following year). OR = odds ratio; no. = number.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Given the strong effect of precollege IR, we conducted exploratory analyses among the larger subset of first-year women with no precollege history of IR. The final four-predictor model (including precollege heavy drinking status, number of sexual partners, sexual enhancement, and disinhibition expectancies) was used to predict likelihood of first-year IR among women who had not previously experienced IR. The overall model likelihood ratio was significant, χ2(4) = 11.36, p = .02, and the only significant predictor was sexual enhancement expectancies (OR = 1.83, SE = 0.36; z = 3.02, p = .003).

Discussion

This study contributes to understanding risk for IR during the first year of college, the year in which female students face the highest risk of rape and sexual assault (Humphrey & White, 2000; Krebs et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2003). We focused on precollege risk factors to guide early prevention efforts before college behavioral patterns are established. Three key findings emerged.

First, precollege history of IR was strongly associated with all of the hypothesized predictors of first-year college IR. Women entering college with a history of IR drank more heavily, used marijuana more often, and had more sex partners than did women with no history of IR. Thus, even though significant prospective associations emerged between (a) precollege heavy drinking and IR and (b) precollege sex partners and IR, these relationships became nonsignificant when precollege IR was included in the model. These data show that before young women arrive on campus, multiple risk factors that contribute to the future likelihood of IR are in place. The observation that multiple risk factors covary highlights the challenges of disentangling these relationships.

Second, the strongest predictor of IR during the first year of college was having a history of IR; 41% of women with a precollege history of IR re-experienced IR in their first year. This finding is consistent with other studies of the transition from high school to college (Parks et al., 2008b; Testa et al., 2010a). A primary explanation for the link between prior and future victimization is the continuation of risk behaviors over time. Individuals who were previously sexually assaulted may continue to have more sexual partners or engage in other risky behaviors such as hookups (Testa et al., 2010a) or heavy drinking (Parks et al., 2008a). A related explanation relates to the potential of sexual assault history to maintain or even increase subsequent heavy drinking. A recent longitudinal study confirms that severe sexual victimization predicts subsequent levels of drinking (and not vice versa), consistent with the view that drinking may serve as a way of coping with the victimization experience(s) (Parks et al., 2014). Early identification of IR victims, beginning in high school, is apriority for (secondary) sexual assault prevention.

Third, sex-related alcohol expectancies increased IR risk in prospective analyses. Students who had experienced IR before college held stronger expectancies for alcohol-related sexual enhancement and disinhibition than those who had not. This finding replicates prior research (Benson et al., 2007; Corbin et al., 2001). Women with precollege sexual experience who started college holding beliefs that alcohol enhances sexual pleasure were more likely to experience IR than women without either characteristic, a prospective relationship that held even when controlling for precollege IR. Importantly, it was sexual enhancement expectancies, rather than precollege heavy drinking, that increased women’s risk for IR in the first year of college, independent of IR history. Sexual enhancement expectancies, when activated by contextual cues, can motivate drinking to achieve valued outcomes and bias attention toward expectancy-related information (Moss & Albery, 2009). The dual-process model of the effect of alcohol on behavior suggests that expectancies, operating largely out of conscious awareness, can influence approach behavior that can ultimately lead to cognitive and behavioral impairment because of the pharmacological effects of alcohol (Cooper, 2006; Moss & Albery, 2009).

The association of alcohol–sex expectancies with the occurrence of IR during the first year of college identifies a new target for sexual assault prevention. Event-level studies of college drinkers establish that more drinking on a given day is associated with increased chances of sexual activity, and that this association is augmented when an individual holds stronger alcohol–sex expectancies (Patrick et al., 2015). Alcohol–sex expectancies predict both engaging in casual sex (outside of a committed relationship) and alcohol-involved rape, each mediated through drinking alcohol before sex (Messman-Moore et al., 2013a; White et al., 2009). How much one drinks is important, given that heavy drinking days (not just any drinking) predict the likelihood of experiencing sexual aggression (Parks et al., 2008a). Our findings add to this growing knowledge base by showing that stronger expectancies of sexual enhancement prospectively predict the likelihood of IR. Importantly, expectancies predate the onset of college drinking patterns.

The observed associations between history of IR, alcohol use, and alcohol expectancies are important given that alcohol use can function both as a risk factor for, and a consequence of, sexual victimization (Griffin et al., 2013; Testa et al., 2010a). Ample research shows that the reasons or motives for drinking predict the likelihood of negative alcohol-related consequences such as IR (Kuntsche et al., 2005). Although IR necessarily involves drinking to incapacitation, contributing factors can be both intrapersonal and interpersonal. Indeed, some perpetrators encourage potential victims to become intoxicated to lessen their ability to resist sexually coercive behavior (Abbey & Jacques-Tiura, 2011; Abbey et al., 2004; Testa & Livingston, 2009). Awareness of the manipulative use of alcohol is also an important element of self-defense (Senn et al., 2015). Therefore, understanding the factors promoting extreme intoxication may be important to preventing IR.

Strengths and limitations of the research

Strengths of the current study include use of a longitudinal prospective design in which precollege predictors were measured before IR outcomes, sampling a large and representative group of first-year women (i.e., one fourth of all incoming female students), use of established and reliable measures, and strong follow-up return rates throughout the study year. To our knowledge, this is one of few longitudinal studies to examine first-year IR, one of few to assess the outcome at more than two time points, and the first prospective study of the impact of alcohol expectancies on IR risk. These strengths enhance confidence in the findings, which significantly build on previous research in highlighting the importance of sex-related alcohol expectancies for IR (Bedard-Gilligan et al., 2011; Marx et al., 2000; Messman-Moore et al., 2013a).

These results should also be considered in light of study limitations. First, as with any study using self-report, the data are subject to inaccuracies because of cognitive and social biases (Schroder et al., 2003). Second, our assessment strategy did not distinguish between incapacitation due to voluntary consumption of alcohol or other drugs and nonconsensual use of date rape or predator drugs such as Rohypnol (Kilpatrick et al., 2007; Testa & Livingston, 2009). Prior research indicates that incapacitation because of voluntary consumption is more common (Lawyer et al., 2010; Littleton et al., 2009), but our data do not allow us to distinguish these two forms. Third, the baseline assessment took place in the first few weeks of the semester, referring back to the month of August. Thus, some students may have arrived on campus during the final few days of the baseline period. Last, our study did not examine risk factors in the college setting. By definition, IR cannot occur without drinking to incapacitation, an acute state with both distal and proximal determinants. It is likely that both precollege and concurrent factors increase the risk of IR.

Implications for sexual assault risk reduction and prevention

This study’s focus on precollege predictors of IR should not be taken to imply that female students are responsible for being raped. However, until perpetration of sexual assault becomes universally unacceptable and rare, development and implementation of strategies under the direct control of potential victims will be needed to reduce women’s risk. Universal prevention programs could include targets suggested by our findings. Specifically, the observation that sex-related alcohol enhancement expectancies predict IR, independent of IR history and heavy drinking, reveals a target for prevention programming. Whereas history of IR cannot be changed, alcohol–sex expectancies can be altered using expectancy challenge interventions (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2012). Furthermore, expectancy challenge protocols can successfully target specific expectancies (Lau-Barraco & Dunn, 2008). Sexual enhancement expectancies may be a promising target for sexual assault prevention. Expectancy challenge interventions could help college students to reduce the association between heavy drinking and sex by weakening expectancies about the “benefits” of alcohol use (Labbe & Maisto, 2011; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2012).

Risk-reduction programming should also address the consistently observed relationship between heavy episodic drinking and sexual assault in general, and IR in particular. Heavy drinking can lead to incapacitation by mobilizing expectancies that promote excessive drinking and/or by reducing ability to recognize intrapersonal and interpersonal risk signals over the course of a drinking episode. Thus, extreme intoxication increases risk for many adverse physical and social outcomes (Barnett et al., 2014; Hingson et al., 2009), including compromising one’s ability to consent to sex and to resist unwanted sex. Emerging evidence suggests that interventions and programs that reduce heavy drinking episodes may also reduce rates of IR (Clinton-Sherrod et al., 2011; Testa et al., 2010b). It is important for health educators and providers to collaborate on alcohol, other drug, and sexual assault risk-reduction programming rather than “siloing” these problems.

Another intervention target that emerges from our research is sexual behavior itself. Alcohol–sex expectancies are associated with more frequently engaging in sex outside of a committed relationship (White et al., 2009), and having more sexual partners increases the odds of encountering a risky situation or a potential perpetrator (Franklin, 2010). Interventions that address sexual practices such as hookups, which often involve ambiguous cues regarding behavioral intentions and situational features that increase risk (Fielder et al., 2013) and have been linked to sexual victimization in prospective analyses (Fielder et al., 2014), are warranted.

The strong relationship between victimization and revictimization suggests the value of targeted interventions for those with a history of IR. To assist women with a history of sexual assault, research needs to refine our understanding of the mechanisms that link prior victimization to revictimization (Classen et al., 2005; Finkelhor & Browne, 1985). Findings from this research can be used to develop interventions. Such efforts must be done carefully and sensitively so that we do not “blame the victim.”

The development and implementation of a suite of complementary interventions can provide the most immediate, powerful, and enduring benefits. Reviews of sexual assault prevention programs suggest that more than a single session is needed to provide sufficient dose and intensity to affect behavioral outcomes (DeGue et al., 2014). Instead, programs offered throughout the college years (Vladutiu et al., 2011) are needed that include (a) preventive interventions for men (Gidycz et al., 2011a), (b) campus-wide interventions to reduce the conditions that support perpetration of sexual assault (Casey & Lindhorst, 2009), and (c) bystander intervention training, which has already been found to be a promising strategy for the prevention of IR (Banyard et al., 2009). Such a comprehensive approach may prove most effective for reducing the unacceptable incidence of sexual assault.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annelise Sullivan for assistance with data collection and the anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R21-AA018257 (to Michael P. Carey). The funding source had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. doi:10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A., Jacques-Tiura A. J. Sexual assault perpetrators’ tactics: Associations with their personal characteristics and aspects of the incident. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:2866–2889. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390955. doi:10.1177/0886260510390955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A., Zawacki T., Buck P. O., Clinton A. M., McAuslan P. Sexual assault and alcohol consumption: What do we know about their relationship and what types of research are still needed? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9:271–303. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00011-9. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard V. L., Moynihan M. M., Crossman M. T. Reducing sexual violence on campus: The role of student leaders as empowered bystanders. Journal of College Student Development. 2009;50:446–457. doi:10.1353/csd.0.0083. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett N. P., Clerkin E. M., Wood M., Monti P. M., O’Leary Tevyaw T., Corriveau D., Kahler C. W. Description and predictors of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences in the first year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:103–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.103. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard-Gilligan M., Kaysen D., Desai S., Lee C. M. Alcohol-involved assault: Associations with posttrauma alcohol use, consequences, and expectancies. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1076–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.001. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson B. J., Gohm C. L., Gross A. M. College women and sexual assault: The role of sex-related alcohol expectancies. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:341–351. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9085-z. [Google Scholar]

- Black M. C., Basile K. C., Breiding M. J., Smith S. G., Walters M. L., Merrick M. T., Stevens M. R. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_report2010-a.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. L., Testa M., Messman-Moore T. L. Psychological consequences of sexual victimization resulting from force, incapacitation, or verbal coercion. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:898–919. doi: 10.1177/1077801209335491. doi:10.1177/1077801209335491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey E. A., Lindhorst T. P. Toward a multi-level, ecological approach to the primary prevention of sexual assault: Prevention in peer and community contexts. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2009;10:91–114. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334129. doi:10.1177/1524838009334129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary E., Coben J. H., Bossarte R. M. Gender and time differences in the associations between sexual violence victimization, health outcomes, and risk behaviors. American Journal of Men's Health. 2008;2:254–259. doi: 10.1177/1557988307313819. doi:10.1177/1557988307313819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen C. C., Palesh O. G., Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2005;6:103–129. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087. doi:10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton-Sherrod M., Morgan-Lopez A. A., Brown J. M., McMillen B. A., Cowell A. Incapacitated sexual violence involving alcohol among college women: The impact of a brief drinking intervention. Violence Against Women. 2011;17:135–154. doi: 10.1177/1077801210394272. doi:10.1177/1077801210394272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. L. Does drinking promote risky sexual behavior? A complex answer to a simple question. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:19–23. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00385.x. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin W. R., Bernat J. A., Calhoun K. S., McNair L. D., Seals K. L. The role of alcohol expectancies and alcohol consumption among sexually victimized and nonvictimized college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:297–311. doi:10.1177/088626001016004002. [Google Scholar]

- DeGue S., Valle L. A., Holt M. K., Massetti G. M., Matjasko J. L., Tharp A. T. A systematic review of primary prevention strategies for sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2014;19:346–362. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.05.004. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermen K. H., Cooper M. L. Sex-related alcohol expectancies among adolescents: I. Scale development. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8:152–160. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.8.3.152. [Google Scholar]

- ElSohly M. A., Salamone S. J. Prevalence of drugs used in cases of alleged sexual assault. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 1999;23:141–146. doi: 10.1093/jat/23.3.141. doi:10.1093/jat/23.3.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder R. L., Walsh J. L., Carey K. B., Carey M. P. Predictors of sexual hookups: A theory-based, prospective study of first-year college women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:1425–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0106-0. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0106-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder R. L., Walsh J. L., Carey K. B., Carey M. P. Sexual hookups and adverse health outcomes: A longitudinal study of first-year college women. Journal of Sex Research. 2014;51:131–144. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.848255. doi:10.1080/00224499.2013.848255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin C. A. Physically forced, alcohol-induced, and verbally coerced sexual victimization: Assessing risk factors among university women. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2010;38:149–159. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.02.004. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz C. A., Orchowski L. M., Berkowitz A. D. Preventing sexual aggression among college men: An evaluation of a social norms and bystander intervention program. Violence Against Women. 2011a;17:720–742. doi: 10.1177/1077801211409727. doi:10.1177/1077801211409727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz C. A., Orchowski L. M., Edwards K. M. Primary prevention of sexual violence. In: Koss M. P., White J. W., Kazdin A. E., editors. Violence against women and children: Navigating solutions. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2011b. pp. 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin M. J., Wardell J. D., Read J. P. Recent sexual victimization and drinking behavior in newly matriculated college students: A latent growth analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:966–973. doi: 10.1037/a0031831. doi:10.1037/a0031831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R. W., Zha W., Weitzman E. R. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. doi:10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey J. A., White J. W. Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00168-3. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D. G., Resnick H. S., Ruggierio K. J., Conoscenti M. A., McCauley J. Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study. Charleston, SC: Medical University of South Carolina; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kimble M., Neacsiu A. D., Flack W. F., Horner J. Risk of unwanted sex for college women: evidence for a red zone. Journal of American College Health. 2008;57:331–338. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.3.331-338. doi:10.3200/JACH.57.3.331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss M. P., Abbey A., Campbell R., Cook S., Norris J., Testa M., White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs C. P., Lindgren K. P., Warner T. D., Fisher B. S., Martin S. L. The Campus Sexual Assault (CSA) study: Final report. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs C. P., Lindquist C. H., Warner T. D., Fisher B. S., Martin S. L. College women’s experiences with physically forced, alcohol- or other drug-enabled, and drug-facilitated sexual assault before and since entering college. Journal of American College Health. 2009;57:639–649. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.6.639-649. doi:10.3200/JACH.57.6.639-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Knibbe R., Gmel G., Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe A. K., Maisto S. A. Alcohol expectancy challenges for college students: A narrative review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:673–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.007. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Barraco C., Dunn M. E. Evaluation of a single-session expectancy challenge intervention to reduce alcohol use among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:168–175. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.168. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer S., Resnick H., Bakanic V, Burkett T., Kilpatrick D. Forcible, drug-facilitated, and incapacitated rape and sexual assault among undergraduate women. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58:453–460. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540515. doi:10.1080/07448480903540515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H., Grills-Taquechel A., Axsom D. Impaired and incapacitated rape victims: Assault characteristics and post-assault experiences. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:439–457. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.4.439. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.24.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx B. P., Nichols-Anderson C., Messman-Moore T., Miranda R., Jr., Porter C. Alcohol consumption, outcome expectancies, and victimization status among female college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30:1056–1070. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02510.x. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J., Ruggiero K. J., Resnick H. S., Conoscenti L. M., Kilpatrick D. G. Forcible, drug-facilitated, and incapacitated rape in relation to substance use problems: Results from a national sample of college women. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:458–462. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore T. L., Coates A. A., Gaffey K. J., Johnson C. F. Sexuality, substance use, and susceptibility to victimization: Risk for rape and sexual coercion in a prospective study of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1730–1746. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314336. doi:10.1177/0886260508314336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore T. L., Ward R. M., DeNardi K. A. The impact of sexual enhancement alcohol expectancies and risky behavior on alcohol-involved rape among college women. Violence Against Women. 2013a;19:449–464. doi: 10.1177/1077801213487058. doi:10.1177/1077801213487058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore T. L., Ward R. M., Zerubavel N. The role of substance use and emotion dysregulation in predicting risk for incapacitated sexual revictimization in women: Results of a prospective investigation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013b;27:125–132. doi: 10.1037/a0031073. doi:10.1037/a0031073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler-Kuo M., Dowdall G. W., Koss M. P., Wechsler H. Correlates of rape while intoxicated in a national sample of college women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:37–45. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.37. doi:10.15288/jsa.2004.65.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss A. C., Albery I. P. A dual-process model of the alcohol-behavior link for social drinking. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:516–530. doi: 10.1037/a0015991. doi:10.1037/a0015991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA Newsletter. Rockville, MD: Author; 2004. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking; p. 3. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/winter2004/Newsletter_Number3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Parks K. A., Hsieh Y.-P., Bradizza C. M., Romosz A. M. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008a;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks K. A., Hsieh Y.-P., Taggart C., Bradizza C. M. A longitudinal analysis of drinking and victimization in college women: Is there a reciprocal relationship? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:943–951. doi: 10.1037/a0036283. doi:10.1037/a0036283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks K. A., Romosz A. M., Bradizza C. M., Hsieh Y.-P. A dangerous transition: Women’s drinking and related victimization from high school to the first year at college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008b;69:65–74. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.65. doi:10.15288/jsad.2008.69.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick M. E., Maggs J. L., Lefkowitz E. S. Daily associations between drinking and sex among college students: A longitudinal measurement burst design. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2015;25:377–386. doi: 10.1111/jora.12135. doi:10.1111/jora.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K. E., Carey M. P., Vanable P. A. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:104–123. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon L. A., Terry D. L., Carey K. B., Garey L., Carey M. P. Efficacy of expectancy challenge interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:393–405. doi: 10.1037/a0027565. doi:10.1037/a0027565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn C. Y., Eliasziw M., Barata P. C., Thurston W. E., Newby-Clark I. R., Radtke H. L., Hobden K. L. Efficacy of a sexual assault resistance program for university women. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:2326–2335. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1411131. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1411131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter L. Involvement of drugs in sexual assault. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2000;45:425–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. H., White J. W., Holland L. J. A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college-age women. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1104–1109. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1104. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Hoffman J. H. Naturally occurring changes in women’s drinking from high school to college and implications for sexual victimization. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:26–33. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.26. doi:10.15288/jsad.2012.73.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Hoffman J. H., Livingston J. A. Alcohol and sexual risk behaviors as mediators of the sexual victimization-revictimization relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010a;78:249–259. doi: 10.1037/a0018914. doi:10.1037/a0018914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Hoffman J. H., Livingston J. A., Turrisi R. Preventing college women’s sexual victimization through parent based intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science. 2010b;11:308–318. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0168-3. doi:10.1007/s11121-010-0168-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Livingston J. A. Alcohol consumption and women’s vulnerability to sexual victimization: Can reducing women’s drinking prevent rape? Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:1349–1376. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961468. doi:10.1080/10826080902961468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Livingston J. A., Vanzile-Tamsen C., Frone M. R. The role of women’s substance use in vulnerability to forcible and incapacitated rape. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:756–764. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.756. doi:10.15288/jsa.2003.64.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., VanZile-Tamsen C., Livingston J. A. Prospective prediction of women’s sexual victimization by intimate and nonintimate male perpetrators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:52–60. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.52. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P., Thoennes N. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2006. Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Vladutiu C. J., Martin S. L., Macy R. J. College- or university-based sexual assault prevention programs: A review of program outcomes, characteristics, and recommendations. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2011;12:67–86. doi: 10.1177/1524838010390708. doi:10.1177/1524838010390708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White House Council on Women and Girls. Rape and sexual assault: A renewed call to action. Washington, DC: Author; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- White H. R., Fleming C. B., Catalano R. F., Bailey J. A. Prospective associations among alcohol use-related sexual enhancement expectancies, sex after alcohol use, and casual sex. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:702–707. doi: 10.1037/a0016630. doi:10.1037/a0016630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. W., Smith P. H. Sexual assault perpetration and reperpetration: From adolescence to young adulthood. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2004;31:182–202. doi:10.1177/0093854803261342. [Google Scholar]