Abstract

Background

Identifying cohorts of Caribbean women with HIV infection rates sufficient for inclusion in HIV vaccine efficacy trials has been challenging. HVTN 907 determined the feasibility of identifying and retaining a cohort of women at high risk for HIV acquisition by focusing recruitment on female sex workers (FSW).

Methods

HIV uninfected FSWs, residing in Haiti, Dominican Republic (DR) and Puerto Rico (PR), who reported unprotected sex and met previously described more stringent site-specific eligibility criteria14, were eligible. Behavioral risk assessment, HIV counseling and testing and pregnancy testing were done at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months.

Results

Among 799 FSWs (264 from DR, 334 from Haiti, 201 from PR), the median age was 26 years, with 54% having less than a high school education and 45% having a monthly household income of less than $US100. Median number of male partners six months prior to screening was 200. Retention at 18 months was 93%. Twelve women became HIV infected, nine from Haiti. The annualized HIV incidence was 1.07 % (95% CI 0.55%, 1.87%). Pregnancy incidence was 22.5% (95% CI 21.9, 29.5%). Statistically significant declines in risk behaviors occurred between screening and the 18 month visit assessment.

Discussion

The HVTN 907 study identified a high risk cohort of women with excellent retention for all 3 sites, despite major challenges especially in Haiti. These results show that a bridging study of a vaccine shown to be efficacious in other clade settings would be possible among FSW in the region, particularly in Haiti.

Keywords: HIV, vaccine trial, women, commercial sex workers, Caribbean

INTRODUCTION

Testing experimental vaccines and other biomedical interventions to prevent HIV infection require study participants at high risk of HIV infection who can comply with a vaccination schedule, adhere to treatments, and complete study follow-up visits to ensure assessments of safety and efficacy1. Women continue to be an important population for participation in studies of HIV biomedical prevention interventions. The HIV prevalence among adults in the Caribbean is about 1.0%, higher than in all other regions outside sub-Saharan Africa2. On the island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic (DR), the combined number of people infected with HIV is 182,000, accounting for approximately 70% of those infected in the Caribbean2,3. The Caribbean is also the only region outside of Africa where the proportion of females living with HIV is higher (53%) than males (47%)3,4. Unprotected heterosexual sex, especially paid or transactional sex, is believed to be the main mode of HIV transmission in the Caribbean. Evidence suggests that the rate of new HIV infections has stabilized in the Caribbean. In 2007, the estimated prevalence of adult HIV infection in the Caribbean was 1.1%, compared with 0.6% in North America and 0.5% in Latin America5,6,7. From 2006-2008, HIV prevalence among female sex workers (FSWs) varied from 2.7-4% in the DR, 8.4% in Haiti, to 27% in Guyana,,8,9,10. In Bermuda and Puerto Rico (PR), unsafe injection drug use (IDU) also contributed significantly to the spread of HIV10,11.

To date, longitudinal cohort studies and HIV vaccine efficacy trials have observed relatively low HIV incidence rates among enrolled women. The vaccine preparedness study, HVTN 903, conducted in 2003-2007, enrolled 453 Caribbean women (252 FSWs from the DR, Jamaica, and PR and 201 high-risk heterosexual women from Haiti, Jamaica, and PR), and over the 12 months of follow-up only 1 FSW from the DR became infected12. The low annualized HIV incidence (0.4%) among Caribbean and South American women in the Step Study, a phase 2b HIV vaccine efficacy trial conducted 2005-2009, pointed to the need to better identify cohorts of women at high risk of HIV-1 infection13,14,15. In these trials, eligibility criteria for women were based predominately on individual-level risk behaviors, including IDU, crack cocaine use, exchanging sex for money or drugs, multiple partners or on limited male partner characteristics such as being HIV-infected or an injection drug user.13

HVTN 907 was an observational cohort study designed to determine the feasibility of recruiting a high incidence cohort of Caribbean women for HIV vaccine efficacy trials using recruitment and eligibility criteria based on sex work and knowledge of local site-specific risk behaviors associated with HIV incidence. The baseline data from this cohort have been previously described14. In this manuscript, we present an analysis of retention, HIV and pregnancy incidence, changes in sexual risk behaviors over time, and concerns regarding HIV vaccine trial participation.

METHODS

Study conduct

HVTN 907 was a prospective observational study of FSWs conducted in Haiti, DR, and PR between 2009 and 2012. Minimum eligibility criteria included exchange of sex for goods, services, or money and unprotected vaginal or anal sex with a man in the previous 6 months. Sites used local epidemiology to develop more stringent criteria as described previously14. Participants had to be females between the ages of 18 to 45, willing to receive HIV test results and risk reduction counseling, not pregnant or intending to become pregnant for 18 months, and provided informed consent. The protocol and informed consent documents were approved by local Independent Ethics Committees.

Study procedures included HIV testing and counseling, pregnancy testing, and assessments of HIV risk at screening and at visits scheduled every 6 months for 18 months. The HIV risk assessment was staff-administered and asked about behaviors in the previous 6 months. Risk reduction counseling was based on CDC guidelines for HIV pre/post-test counseling, and condoms were provided at each visit. A risk assessment tool was used to ensure that appropriate risk assessment, risk reduction counseling, and participant education were provided. At enrollment and the 18-month follow-up visit, staff administered a questionnaire about attitudes regarding HIV/AIDS and concerns regarding and willingness to participate in future HIV preventative vaccine trials. Women who became HIV-infected were terminated from the study and referred for care.

Statistical analysis

The aim of the study regarding HIV incidence was to rule out, with high probability, that the incidence rate was less than 1%. With a sample size of 800, if 18 or more infections were observed, we could conclude with 97.5% confidence that the true incidence was at least 1.0% per year (lower bound of 95% CI for 18 infections). If the observed number of infections was 8 or fewer, we could conclude with 97.5% confidence that the true incidence was no more than 1.5% per year (upper bound of 95% CI for 8 infections).

Person-years for HIV incidence rates were measured from enrollment to the date of the first positive HIV test for infected women or to the date of the last negative test for uninfected women. For pregnancy rates among non-sterilized women, person-years were calculated from enrollment to last pregnancy assessment with the time women were pregnant, subtracted. The date of conception was estimated as 266 days (average full-term pregnancy) prior to the estimated delivery date.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess predictors of time to HIV infection, and logistic regression models used to assess predictors of retention at 18 months among HIV-uninfected women and pregnancy among non-sterilized women. Predictors assessed included: study site, demographics, housing, incarceration history, sex work history, and baseline HIV risk behaviors (substance use, STIs, sexual risk, and male partner risk factors). We evaluated baseline risk behaviors as these would be the most informative for future recruitment of high risk cohorts. Additionally, we assessed not using birth control reported at the enrollment visit in the pregnancy models. A best subset model selection approach was used to identify the best fit model based on the Aikaike information criterion. Since this method can result in non-significant predictors in the model, the effect of deleting the non-significant variables was assessed to obtain a final model containing only significant predictors. A predictor was considered statistically significant if the Wald p-value was < 0.05 or the confidence interval for the hazard ratio (infection model) or odds ratio (retention, pregnancy models) excluded 1.

Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were used to assess changes in the average number of partners and percentages of women reporting risk behaviors over time, adjusting for predictors of dropout. GEE modeling was selected since it accounts for the within subject correlation between assessment times in reporting a behavior. Changes between baseline and 18 months, baseline and 6 months, and 6 and 18 months were assessed, with score test p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant. McNemar tests were used to test for change in the items of concern regarding vaccine trial participation and willingness to participate between the enrollment and 18-month visit for women who completed both questionnaires. For statistical testing, the item of concern were dichotomized as very/somewhat concerned and not concerned at all and willingness as definitely/probably willing and probably not/definitely not willing.

RESULTS

Cohort characteristics

The study enrolled a total of 799 FSWs at the 3 study sites between May 2009 and July 2010. The median age of the cohort was 26, with more than half (54%) having less than a high school education and 45% having a monthly household income of less than $US 100 (Table 1). The median number of male partners in the 6 months prior to screening was 200, with all except 4 women reporting unprotected vaginal sex and 25% reporting unprotected anal sex. Almost a third (30%) had been forced to have sex, mostly by a client (28%). IDU was reported by 26 of the women primarily in PR, whereas non-IDU (30%) and heavy drinking (42%) were more common. Only 9 women knew they had an HIV-positive partner and 70% reported having an at-risk partner (injection drug user, incarcerated, had sex with men, exchanged sex, or had concurrent women partners).

Table 1.

Demographics and HIV risk behaviors within the 6 months preceding screening for enrolled participants

| Dominican Republic (N=264) | Haiti (N=334) | Puerto Rico (N=201) | All Sites (N=799) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median(IQR) | 26 (21, 32) | 23 (20, 27) | 30 (26, 35) | 26 (21, 30) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 211 (79.9%) | 186 (55.7%) | 36 (17.9%) | 433 (54.2%) |

| High School | 53 (20.1%) | 148 (44.3%) | 138 (68.7%) | 339 (42.4%) |

| Undergraduate | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 27 (13.4%) | 27 (3.4%) |

| Monthly household income | ||||

| < $100 | 2 (0.8%) | 327 (99.4%) | 19 (10.0%) | 348 (45.1%) |

| $100 - <$500 | 125 (49.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 113 (59.5%) | 240 (31.1%) |

| ≥ $500 | 125 (49.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 58 (30.5%) | 183 (23.7%) |

| Missing | 12 | 5 | 11 | 28 |

| Household income supports children | 242 (91.7%) | 289 (86.5%) | 127 (63.2%) | 658 (82.4%) |

| Housing | ||||

| Homeless | 10 (3.8%) | 28 (8.4%) | 50 (24.9%) | 88 (11.0%) |

| Not likely to be living in the same place within 6 months | 64 (24.2%) | 120 (35.9%) | 24 (11.9%) | 208 (26.0%) |

| Ever spent time in jail/prison | 66 (25.0%) | 5 (1.5%) | 67 (33.3%) | 138 (17.3%) |

| Number of male partners | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 113 (60, 188) | 780 (520, 1008) | 10 (6, 26) | 200 (31, 690) |

| 10 or more clients per week | 37 (14.0%) | 322 (96.4%) | 6 (3.0%) | 365 (45.7%) |

| Exchanged sex on the street | 52 (19.7%) | 183 (55.0%) | 60 (29.9%) | 295 (37.0%) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Had a main partner | 85 (32.2%) | 96 (28.7%) | 120 (59.7%) | 301 (37.7%) |

| Unprotected vaginal sex | 263 (99.6%) | 332 (99.4%) | 200 (99.5%) | 795 (99.5%) |

| Unprotected anal sex | 59 (22.3%) | 55 (16.5%) | 83 (41.3%) | 197 (24.7%) |

| Had a partner who forced the participants to have sex | 57 (21.6%) | 165 (49.4%) | 20 (10.0%) | 242 (30.3%) |

| Heavy drinkingb | 223 (84.8%) | 9 (2.7%) | 100 (49.8%) | 332 (41.7%) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Non-injection drug use | 63 (23.9%) | 19 (5.7%) | 154 (76.6%) | 236 (29.5%) |

| Had an HIV+ partner | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.5%) | 4 (2.0%) | 9 (1.1%) |

| No | 6 (2.3%) | 19 (5.7%) | 74 (36.8%) | 99 (12.4%) |

| Don't Know | 258 (97.7%) | 310 (92.8%) | 123 (61.2%) | 691 (86.5%) |

| Had a partner who had been in jail/prison | ||||

| Yes | 105 (39.8%) | 33 (9.9%) | 61 (30.3%) | 199 (24.9%) |

| No | 3 (1.1%) | 93 (27.8%) | 88 (43.8%) | 184 (23.0%) |

| Don't Know | 156 (59.1%) | 208 (62.3%) | 52 (25.9%) | 416 (52.1%) |

| Had a partner who injected drugs | ||||

| Yes | 12 (4.5%) | 66 (19.8%) | 34 (16.9%) | 112 (14.0%) |

| No | 15 (5.7%) | 94 (28.1%) | 125 (62.2%) | 234 (29.3%) |

| Don't Know | 237 (89.8%) | 174 (52.1%) | 42 (20.9%) | 453 (56.7%) |

| Had a partner who had concurrent women partners | ||||

| Yes | 155 (58.7%) | 199 (59.9%) | 142 (70.6%) | 496 (62.2%) |

| No | 1 (0.4%) | 19 (5.7%) | 8 (4.0%) | 28 (3.5%) |

| Don't Know | 108 (40.9%) | 114 (34.3%) | 51 (25.4%) | 273 (34.3%) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Had a partner who exchanged sex with other women | ||||

| Yes | 122 (46.2%) | 119 (35.8%) | 77 (38.3%) | 318 (39.9%) |

| No | 2 (0.8%) | 45 (13.6%) | 24 (11.9%) | 71 (8.9%) |

| Don't Know | 140 (53.0%) | 168 (50.6%) | 100 (49.8%) | 408 (51.2%) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Had an partner who had sex with men | ||||

| Yes | 13 (4.9%) | 11 (3.3%) | 13 (6.5%) | 37 (4.6%) |

| No | 10 (3.8%) | 63 (18.9%) | 82 (40.8%) | 155 (19.4%) |

| Don't Know | 241 (91.3%) | 259 (77.8%) | 106 (52.7%) | 606 (75.9%) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

IQR = interquartile range

a Differences between sites were statistically significant for all items at p ≤ 0.0001 except unprotected vaginal sex.

Heavy drinking was defined as ≥ 6 drinks per day or 4-5 drinks every day on average.

Retention

Overall, 93% (n=742) of women completed the 6-month visit, 92% (n=739) completed the 12-month visit, and 93% (n=747) completed the 18-month visit or were diagnosed as HIV infected prior to the visit. Retention rates were similar for the DR (97%) and Haiti (96%), and lower for PR (84%). The major reasons for drop-out were unable to contact the woman (26 out of 52 drop-outs), unable to adhere to the visit schedule (12) or the woman relocated (9). In logistic regression modeling, the only significant predictor of drop-out among HIV non-infected women, after adjusting for enrollment at PR, was whether the woman reported at screening that she was not likely to be living in the same place in 6 months (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=2.2, 95% CI 1.1, 4.3).

HIV infections

Twelve women became infected on-study, 9 from Haiti, 2 from DR, and 1 from PR. With 1119 person-years of follow-up, the annualized HIV incidence rate was 1.07% (95% CI 0.55%, 1.87%, Table 2). One infection was detected at the 6-month visit, 7 at the 12-month visit, and 4 and the 18-month visit. Because of the small number of infections, Cox proportional hazard models were limited to assessing risk behaviors individually while adjusting for site. Exchanging sex on the street was the only statistically significant predictor of HIV infection [hazard ratio (HR)=4.3, 95% CI 1.1, 17.1)]. Forced to have sex was of borderline significance [HR=3.2, 95% CI 0.9, 11.3].

Table 2.

HIV incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals

| HIV incidence |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | # enrolled | # with post-enrollment test | # infections | Observed person-years | Annualized rate | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Dominican Republic | 264 | 262 | 2 | 398.4 | 0.50% | (0.06%, 1.81%) |

| Haiti | 334 | 330 | 9 | 466.5 | 1.93% | (0.88%, 3.66%) |

| Puerto Rico | 201 | 189 | 1 | 254.3 | 0.39% | (0.01%, 2.19%) |

| All Sites | 799 | 781 | 12 | 1119 | 1.07% | (0.55%, 1.87%) |

Pregnancy

Among the 634 women who reported not being surgically sterilized at baseline, the incidence of pregnancy was 22.5% (95% CI 21.9%, 29.5%), with 171 women reporting a total of 181 pregnancies (Table 3). The DR had the highest incidence, 40.0%, followed by Haiti 21.4% and PR 13.8%. The median time to first pregnancy was 231 days (Table 3). Two-thirds (67%) of pregnancies with a known outcome (n=129) resulted in a full-term live birth (Table 3). Haiti had a higher percentage of pregnancies terminated by therapeutic or elective abortion, 27%, compared to the DR 5% and none reported for PR. None of the women who became HIV-infected had a pregnancy on study.

Table 3.

Pregnancy rates among non-sterilized women, timing and outcomes

| Dominican Republic | Haiti | Puerto Rico | All Sites | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women enrolled | 264 | 334 | 201 | 799 |

| Non-sterilized women at enrollment | 206 | 332 | 96 | 634 |

| # Women who became pregnant | 73 | 86 | 12 | 171 |

| # of Pregnancies | 78 | 90 | 13 | 181 |

| Annualized pregnancy rate | 40.0% | 21.4% | 13.8% | 25.5% |

| (95% confidence interval) | (31.6%, 49.9%) | (17.2%, 26.3%) | (7.3%, 23.6%) | (21.9%, 29.5%) |

| Timing of first pregnancy following enrollment | ||||

| 0-6 months | 25 (34.2%) | 34 (39.5%) | 4 (33.3%) | 63 (36.8%) |

| >6 - 12 months | 29 (39.7%) | 33 (38.4%) | 6 (50.0%) | 68 (39.8%) |

| >12 months | 19 (26.0%) | 19 (22.1%) | 2 (16.7%) | 40 (23.4%) |

| Median (days) | 247 | 213 | 242 | 231 |

| 25th, 75th percentile | 144, 372 | 111, 335 | 81, 324 | 125, 364 |

| Known outcomes | ||||

| Full-term live birth | 45 (71.4%) | 38 (64.4%) | 4 (57.1%) | 87 (67.4%) |

| Premature live birth | 8 (12.7%) | 2 (3.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | 12 (9.3%) |

| Fetal death/still born | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Spontaneous abortion | 7 (11.1%) | 3 (5.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (7.8%) |

| Ectopic pregnancy | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Therapeutic/elective abortion | 3 (4.8%) | 16 (27.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 19 (14.7%) |

| Unknown outcome | 15 | 31 | 6 | 52 |

Factors identified as positively associated with pregnancy in a multivariable logistic regression model were: enrolled at the DR (aOR=1.9, 95% CI 1.3, 2.8), having a household income that supported children (aOR=1.9, 95% CI 1.1, 3.4), having a main partner (aOR=1.6, 95% CI 1.0, 2.4), and having an MSM partner (aOR=2.9, 95% CI 1.1, 7.4). Factors having a negative association were older age (aOR=0.9 per 1 year increase, 95% CI 0.9, 1.0), recreational drug use (aOR=0.6, 95% CI 0.3, 1.0) and having a partner who had concurrent women partners (aOR=0.5, 95% CI 0.3, 0.7).

Risk behaviors

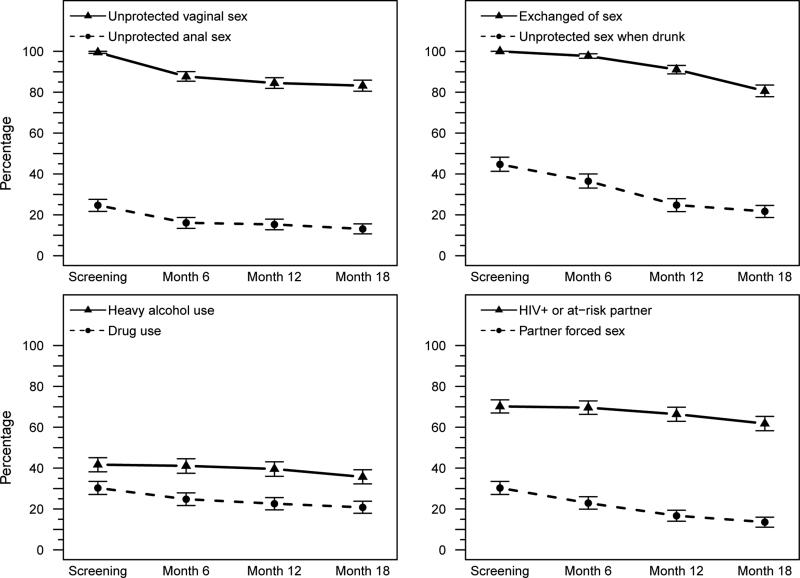

The median number of male partners declined significantly from 200 at screening, 121 at 6 months, 70 at 12 months and 17 at 18 months (p < 0.001 screening to 18 months). Statistically significant declines in sexual risk behaviors of the women and heavy alcohol and drug use were observed between the screening and the 18 month visit assessment (Fig 1). Except for exchange of sex and heavy alcohol use, changes occurred within the first 6 months on study as well as from 6 to 18 months. The majority of women (86% at baseline to 77% at 18 months) did not know if they had an HIV-positive partner. The percentages of women having an HIV-positive or an at-risk partner were the same at screening and 6 months (70%) and declined at 12 (66%) and 18 months (62%) (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Risk behaviors by assessment time.

4 panels showing risk behaviors in the cohort (not broken down by site). Panel descriptions include p-values for differences between screening visit to 18 months, screening visit to 6 months and 6 to 18 months. Panel A: unprotected vaginal sex (<0.001, <0.001, .003) and unprotected anal sex (<0.001, <0.001, 0.02). Panel B: Exchange of sex (--, --, <0.001) and unprotected sex when drunk (<0.001, <0.001, <0.001). Panel C: Heavy alcohol use (<0.001, not significant, <0.001) and drug use (<0.001, <0.001, <0.001). Panel D: HIV positive/at-risk partner (<0.001, not significant, <0.001) and partner forced sex (<0.001, <0.001, <0.001). p-values were from GEE model score test statistics testing the null hypothesis that the behavior is the same at the two time points. The GEE models used a logit link (logistic regression) and an exchangeable correlation structure. Non- significant p-value were greater than 0.05.

Future HIV vaccine trial participation

At enrollment, 85% (680/799) of women and at 18 months, 88% (648/737) cited being very concerned about at least 1 of the 11 items regarding HIV vaccine trial participation. For all items, women from Haiti had the least degree of concern. The items of most concern at both visits were permanent injury or death, testing positive on standard HIV tests, and long-term side-effects (Table 4). Concern over these increased between enrollment and month 18 for women with data from both visits (permanent injury/death p <0.0001, testing positive p=0001, long-term side effects p=0.002). Concern regarding short-term side effects and a partner wanting to have unprotected sex decreased over time (p=0.02 and 0.005, respectively).

Table 4.

Items of concern regarding HIV vaccine trial participation and willingness to participate in a future triala

| Items of Concern Regarding Vaccine Trial Participation | Enrollment (N=799) | 18 Months (N=737) |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term side effects from the injection, such as fever, aches and pains, and pain or infection at the injection site | ||

| Very concerned | 122 (15.3%) | 93 (12.6%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 251 (31.4%) | 208 (28.2%) |

| Not concerned at all | 426 (53.3%) | 436 (59.2%) |

| Long-term side effects | ||

| Very concerned | 332 (41.6%) | 339 (46.0%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 229 (28.7%) | 222 (30.1%) |

| Not concerned at all | 238 (29.8%) | 176 (23.9%) |

| Having multiple HIV tests during the study | ||

| Very concerned | 58 (7.3%) | 32 (4.3%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 87 (10.9%) | 71 (9.6%) |

| Not concerned at all | 652 (81.8%) | 634 (86.0%) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 |

| Testing positive on standard HIV test because of receipt of the vaccine | ||

| Very concerned | 382 (47.8%) | 415 (56.3%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 219 (27.4%) | 193 (26.2%) |

| Not concerned at all | 198 (24.8%) | 129 (17.5%) |

| Spouse/Partner not wanting to have sexual relations | ||

| Very concerned | 220 (27.5%) | 189 (25.6%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 196 (24.5%) | 184 (25.0%) |

| Not concerned at all | 383 (47.9%) | 364 (49.4%) |

| Spouse/partner feels you are protected against HIV and insists on intercourse without a condom | ||

| Very concerned | 208 (26.0%) | 171 (23.2%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 297 (37.2%) | 241 (32.7%) |

| Not concerned at all | 294 (36.8%) | 325 (44.1%) |

| Other Negative reactions of family/friends | ||

| Very concerned | 172 (21.5%) | 146 (19.9%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 177 (22.2%) | 148 (20.1%) |

| Not concerned at all | 449 (56.3%) | 441 (60.0%) |

| Missing | 1 | 2 |

| Not being able to donate/sell blood while in the study | ||

| Very concerned | 116 (14.5%) | 128 (17.4%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 124 (15.5%) | 111 (15.1%) |

| Not concerned at all | 558 (69.9%) | 498 (67.6%) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Job discrimination | ||

| Very concerned | 214 (26.8%) | 200 (27.1%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 162 (20.3%) | 140 (19.0%) |

| Not concerned at all | 422 (52.9%) | 396 (53.8%) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 |

| Permanent injury or death | ||

| Very concerned | 562 (70.4%) | 584 (79.2%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 72 (9.0%) | 79 (10.7%) |

| Not concerned at all | 164 (20.5%) | 74 (10.0%) |

| Missing | 1 | |

| Avoiding pregnancy during the study | ||

| Very concerned | 81 (10.1%) | 80 (10.9%) |

| Somewhat concerned | 57 (7.1%) | 58 (7.9%) |

| Not concerned at all | 661 (82.7%) | 599 (81.3%) |

| Willingness to participate in an HIV vaccine trial | ||

| definitely willing | 461 (57.7%) | 288 (39.1%) |

| probably willing | 249 (31.2%) | 338 (45.9%) |

| probably not willing | 45 (5.6%) | 70 (9.5%) |

| definitely not willing | 44 (5.5%) | 41 (5.6%) |

Site staff administered a questionnnaire that asked women, “if you were thinking of joining an HIV vaccine study, how concerned would you be about the following?” Specific items of concern are listed in the table in the same order as the questionnaire.

Despite concerns about certain aspects of HIV vaccine trial participation, the majority of women (78%, n=573) said at both enrollment and month 18 that they were definitely or probably willing to participate in a future HIV vaccine trial, whereas only 4% (n=30) said they were probably or definitely not willing at both visits. However, more women changed from being willing at enrollment to not willing at month 18 (11%, n=81) than those who changed from unwilling to willing (7%, n=53, p=0.02).

DISCUSSION

Our study identified a high-risk population of women with an annualized HIV incidence rate >1% (1.07%) in the context of ongoing risk-reduction counseling and prevention resources, with 93% retention over the 18-months of follow-up. Although an incidence rate of 0.55% (lower bound of 95% CI) could not be ruled out, our HIV incidence rate was higher than that seen for women in HVTN 903 (0.5% for the DR and 0% for Haiti, Jamaica and PR)12 and in the Step HIV vaccine efficacy trial among Caribbean and South American women (0.4%)15, which used less stringent eligibility criteria. Our incidence was also higher than that seen in 2 recent cohort studies conducted in the US among at-risk women in high HIV prevalence areas; both observed annual incidence rates of 0.3%16,17. The low incidence observed in the US studies makes the possibility of conducting a preventative HIV vaccine trial with sufficient sample size to assess vaccine efficacy in a clade B setting among at-risk women unlikely16,17,18,19. However, once an HIV vaccine is shown to be safe and efficacious for women in another clade setting, conducting a bridging study, based on correlates of protection, to support licensure of that vaccine for at-risk women in a clade B setting, would be possible among FSWs in the Caribbean, particularly in Haiti.

Haiti had the highest HIV incidence (1.9%) of the 3 sites and also used the most stringent eligibility criteria including exchanging sex for money in the past 6 months and unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse with at least 10 male clients per week for the past 8 weeks. Co-factors associated with an increase of HIV infection were exchanging sex on the street and with borderline significance, having a partner who forced sex, both of which were more prevalent in the Haitian cohort. The feasibility of applying the stringent eligibility criteria used by Haiti in HIV prevention trials conducted in other clade B locations should be assessed. It is possible, however, that the use of these stringent criteria and HIV prevalence observed in Haiti are not feasible in some other clade B countries due to differing levels of interventions to and other characteristics of female sex workers20,21,22,23.

From a public health perspective, the incidence rate seen in HVTN 907 is of concern and suggests the need for urgent intervention in the region. Preventing new HIV infections in the Caribbean is essential as it constitutes the region with the most intense clade B epidemic in women4.

This study indicated that recruitment strategies that took into account local epidemiological, behavioral and geographical considerations were successful with good retention of participants. These results are encouraging, because HIV vaccine trials generally require multiple clinic visits over 1-3 years of active follow-up. A significant predictor of study dropout was a participant reporting at screening that she was not likely to be living in the same place during the 6 months following screening. This finding highlights the importance of collecting data on living arrangements in future trials and providing additional retention messaging and assistance to women who are more mobile.

All sites used extensive peer street outreach, confirmed contact information throughout the study, and provided medical and other services specific to the local population and individuals. The PR site retention strategies included distribution of prevention kits with condoms, identification cards, lubricants and other items, transportation fees to attend the clinic, and monetary compensation approved by the IRB. In addition, free gynecologic, family planning, medical, and social services were provided.

The DR site provided calendar cards for visits, made reminder calls, and accommodated participants’ schedule for clinic visits, including irregular clinic hours and a space for and help with their children while in the clinic. Special dates were celebrated such as Day of Voluntary Service, Vaccine Awareness Day, World AIDS Day, mother's day, and Christmas. Education sessions were key factors for building strong relationships and helping participants strengthen their self-esteem. Psychologists and fieldworkers also visited volunteers during crises such as recent positive HIV result, intra-familiar violence, loss of a relative, and natural disasters.

Haiti experienced major challenges during this study due to the catastrophic January 2010 earthquake. The resilience and determination of GHESKIO staff was demonstrated by providing acute care to refugees24 while conducting research and delivering usual HIV-related services. Participants were contacted by cell phone or through active contact by the experienced fieldworkers and peer educators (mainly former FSWs). The site provided cell phones with pre-paid cards and snacks at each visit and social activities and health services to family members when necessary. Immediately following the earthquake, the GHESKIO team developed contingency plans with weekly group meetings to reinforce support sessions and retention, and gave FSWs the opportunity to discuss the tragedy and express problems in their daily life. Interim contacts were conducted on the streets at night to maintain adherence and follow-up at the clinic. Although the earthquake was an exceptional occurrence, HIV prevention studies are often conducted in regions lacking good infrastructure back-up and/or subject to political instability. Careful thought needs to be given when planning a trial as to how to maintain communication with staff, participants, and trial sponsors during an emergency and if administration of study products would be possible outside of the clinic setting. If a disaster occurs, site staff need to take quick, innovative action to develop a specific contingency plan24.

Self-reported high- risk behavior decreased over time among our cohort, possibly suggesting social desirability bias or that the counseling provided during the trial was effective at reducing HIV risk. The reduction in risk may be due to more risky women dropping out of the trial, although this is an unlikely explanation given the high retention rates and no baseline risk behaviors were predictive of retention. The pattern of risk decreasing in a trial cohort has been seen in previous studies among at-risk women where percentages reporting 1 or more episodes of unprotected anal or vaginal sex declined between baseline and the month 6 assessments and then plateau12,13,16. Efficacy trials require close monitoring to ensure that observed HIV incidence is high enough to evaluate vaccine efficacy when risk is decreasing in part of the cohort.

Despite reductions in risk behaviors and lower HIV incidence at the DR and PR sites, these cohorts of women were having unprotected sex as demonstrated by the high annualized pregnancy rate of 22.5%. This finding has been observed previously in the Step Study and in US cohort of at-risk womenError! Reference source not found.16. In our study, having a main partner and having a household income that supported children were associated with subsequent pregnancy. Perhaps these indicators represent more stable conditions. Although asking women to forgo pregnancy for 18 months may have been unrealistic, it is worrisome for future HIV vaccine trials that over a third of the pregnancies occurred within the first 6 months of the study. The risks of experimental HIV vaccines on fetal development are unknown and may be greatest during the most intensive vaccinations periods, which typically occur early in a trial. Also, pregnancy would be a reason for stopping vaccinations on an HIV vaccine trial, diminishing the ability to assess vaccine efficacy. Understanding both regional and individual factors associated with pregnancy are important for future HIV vaccine trials. In an HIV vaccine trial, the importance of avoiding pregnancy during the vaccination phase for safety should be made clear prior to enrollment. Effective pregnancy prevention counseling messages and access to effective contraception are needed during vaccine trials.

Despite the concerns about certain aspects of HIV vaccine trial participation, the majority of participants indicated willingness to participate in an HIV vaccine study. The high concern expressed about long-term side effects/permanent injury indicates that these are areas that will need to be adequately addressed in the informed consent process. Testing HIV positive on standard HIV tests was also of high concern.

In conclusion, recruitment and retention of FSWs was feasible and successful with eligibility criteria, especially in Haiti, resulting in a cohort with sufficient HIV incidence for HIV vaccine bridging trials in the region.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This research was supported by the HIV Vaccine Trials Network, which is funded through a cooperative agreement with the Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health, grants UO1AI068614, UO1AI068635, UO1AI068618, U01AI069415, 5U01AI069421, and 5U01AI069486.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the AIDS Vaccine Conference, Barcelona, Spain, October, 2013.

Conflicts of Interest: No conflicts were declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson MI, Fauci AS. An HIV vaccine- Challenges and prospects. N Engl J Medicine. 2008;389:888–890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0806162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [June 26, 2014];How to get to zero: Faster. Smarter. Better. UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report, 2011. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/JC2216_WorldAIDSday_report_2011_en.pdf.

- 3.The status of HIV in the Caribbean. UNAIDS; 2010. Available at http://www.unaidscaribbean.org. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaughan HE, Cane P, Pillay D, et al. Charaterization of HIV type 1 clades in the Carribean using pol gene sequences. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19(10):929–932. doi: 10.1089/088922203322493120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 09 Aids epidemic update. http//data.unaids.org/pubReport/2009/JC1700_Epi_Update_2009_en pdf. [PubMed]

- 6.Halperin DT, de Moya EA, Perez-Then E, Pappas G, Calleja J. Understanding the HIV epidemic in the Dominican Republic : a prevention success story in the Craibbean. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune deficiency Syndromes. 51:S52–S59. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a267e4. >M>G 92009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW. HIV Disease in the Caribbean, Topics Antiviral Medicine 2011. IAS-USA; [Google Scholar]

- 8.PSI Research & Metrics HIV Prévalence VIH et utilisation de condom parmi les travailleuses du sexe Haïtiennes. Rapport sommaire TRaC Summary. 2012 Available at : < http://www.psi.org/resources/publications>.

- 9.Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2011, HIV Surveillance Report. 23 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/2011/surveillance_Report_vol_23.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diagnoses of HIV infection among adult and adolescent Hispanics/Latinos, by transmission category and place of birth, 2011—United States and 6 dependent areas. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2011_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_23.pdf#Page=36.

- 11.Stage 3 (AIDS) among adult and adolescent Hispanics/Latinos, by transmission category and place of birth, 2011—United States and 6 dependent areas. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2011_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_23.pdf Pag=37.

- 12.Djomand G, Metch B, Zorilla C, et al. The HVTN Protocol 903 vaccine preparedness Study: LessonS learned in preparation for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. AIDS. 2008;48:82–89. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817236ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novak RM, Metch B, Buchbinder S, et al. Risk behavior among women enrolled in a randomized controlled efficacy trial of an adenoviral vector vaccine to prevent HIV acquisition. AIDS. 2013;27:1763–70. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328360c83e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deschamps MM, Zorilla CD, Morgan CA, et al. Recruitment of Caribbean female commercial sex workers at high risk of HIV infection. Pan American Journal of Public Health. 2013;34(2):92–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Fitzgerald D, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine – The STEP study: a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, test of concept trial. The Lancet. 2008:1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koblin BA, Metch B, Novack RM, et al. Feasibility of identifying a cohort of US women at high risk for HIV infection for HIV vaccine efficacy trials:longitudinal results of HVTN 906. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:239–244. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828ded1a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodder SL, Justman J, Hughes JP, et al. HIV acquisition among women from selected areas of the United States a cohort study. Ann Intern Medi. 2013;158:10–18. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–29. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harmers FF, Downs AM. The changing face of the HIV epidemic in western Europe: What are the implications for public health policies? The Lancet. 2004;364:83–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16594-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy C, Barrington C, Donastory Y, et al. Exploring the positive health, dignity and prevention needs of female sex workers, men who have sex with men and transgender women in the Dominican Republic and Swaziland. USAID | Project Search: Research to Prevention; Baltimore: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerrigan D, Barrington C, Sweat M, et al. Environmental-structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(1):120–125. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerrigan D, Moreno L, Rosario S, Sweat M. Adapting the Thai 100% condom programme: developing a culturally appropriate model for the Dominican Republic. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2001;3(2):221–240. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrington C, Moreno L, Kerrigan D. Local understanding of an HIV vaccine and its relationship with HIV-related stigma in the Dominican Republic. AIDS Care. 2007 Aug;19(7):871–7. doi: 10.1080/09540120701203295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pape JW, Deschamps MM, Ford H, et al. The GHESKIO refugee camp after the earthquake in Haiti-dispatch 2 from Port Au Prince. NEJM. 2010;362:e34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMpv1001785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]