Abstract

Cohabitation is now the modal first union for young adults, and most marriages are preceded by cohabitation even as fewer cohabitations transition to marriage. These contrasting trends may be due to compositional shifts among cohabiting unions, which are increasingly heterogeneous in terms of cohabitation order, engagement, and the presence of children, as well as across socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. The author constructs 5-year cohabitation cohorts for 18- to 34-year-olds from the 2002 and 2006–2010 cycles of the National Survey of Family Growth (n = 17,890 premarital cohabitations) to examine the outcomes of cohabitations over time. Compared to earlier cohabitations, those formed after 1995 were more likely to dissolve, and those formed after 2000 were less likely to transition to marriage even after accounting for the compositional shifts among individuals in cohabiting unions. Higher instability and decreased chances of marriage occurred among both engaged and non-engaged individuals, suggesting society-wide changes in cohabitation over time.

Keywords: adolescence, cohabitation, demography, family structure, marriage, close relationships

The transition to adulthood now seem to includes at least one spell of cohabitation, given that the majority of adults in their 30s have cohabited (Chandra, Martinez, Mosher, Abma, & Jones, 2005; Manning, 2013). This reflects the fact that although young adults are delaying marriage, they are still forming romantic unions (Raley, 2001). However, fewer cohabitations are transitioning to marriage (Bumpass & Lu, 2000), and more individuals are experiencing multiple cohabitations (Lichter, Turner, & Sassler, 2010), suggesting that cohabitation is becoming de-linked from marriage. At the same time, though, most marriages are preceded by cohabitation (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008) even as fewer cohabitations are begun with marital intentions (Vespa, 2014). Thus, among young adults, marriage seems to be less of a part of the cohabitation process even as cohabitation has become more strongly linked to the marriage process.

Cohabitation is now a normative and acceptable union for young adults, in part because of delays in first marriage and the prolongation of young adulthood (Settersten & Ray, 2010). The proportion of women age 19–24 who had ever cohabited, for instance, increased by over 30% between the late 1980s and 2010 (Manning, 2013). Relationships early in adulthood, however, are highly unstable, and more young adults are forming higher order unions, as evidenced by the rise in serial cohabitation (Cohen & Manning, 2010; Lichter et al., 2010). Commitment to marriage at the start of cohabitation, too, seems to be waning among young adults (Vespa, 2014), with those entering their union with marriage plans perhaps an increasingly select group with the strongest chances of marriage. Shifts in the socioeconomic and demographic profiles of cohabitors, such as a growing proportion of minority cohabitors or more cohabitors with children, may also contribute to changes in the outcomes of cohabiting unions over time. Therefore, examining trends in cohabiting outcomes during young adulthood requires increased attention to the potential role of compositional differences.

In this research I explicitly examined, using the 2002 and 2006–2010 cycles of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg.htm), whether the link between cohabitation and marriage is changing among never-married young adults age 18–34. If the link between cohabitation and marriage has changed, we would expect that with each successive cohabitation cohort fewer cohabitations will transition to marriage as more cohabitations dissolve. Alternatively, if differences across cohorts are minimal after accounting for shifts in key relationship characteristics, such as initial marital intentions (proxied by engagement status), cohabitation order, and the presence of children, as well as socioeconomic and demographic shifts, this would suggest that compositional differences among cohabitors are primarily responsible for the observed changes in the outcomes of cohabiting unions, with a greater proportion of cohabitations over time composed of those with an elevated risk for dissolution and lower risk for marriage. In this research I also tested the possibility that having marital intentions at the start of cohabitation is becoming more selective of individuals likely to marry, by exploring whether trends in cohabitation outcomes differ by engagement status.

Background

Although the age at marriage has risen (Kawamura, 2009), young adults are still forming coresidential unions at roughly the same ages, with their first union increasingly likely to be cohabitation (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008; Raley, 2001). By 2009–2010, 60% of women age 19–44 had ever cohabited, nearly double the proportion of 33% in 1987 (Manning, 2013). As cohabitation has become more common, researchers have attempted to understand how it fits into the relationship spectrum (Guzzo, 2006; Smock, 2000), variously characterizing cohabitation as an alternative to being single, a stage in the marriage process (either as a precursor to marriage or a trial marriage), and as an alternative to marriage. Characterization attempts, however, are complicated by the heterogeneous nature of cohabitors, because cohabitation is common across racial/ethnic groups, socioeconomic statuses, prior parenthood and union experiences, and so on. In the late 1990s, cohabitation in the United States largely seemed to function as an alternative to being single (Heuveline & Timberlake, 2004), despite the fact that most cohabitors expected to marry their partners (Brown, 2000). However, the rapid pace of change in union and family behaviors suggests that “what we know about intimate sexual unions can quickly become outdated” (Raley, 2000, p. 36), warranting continued attention.

To understand whether, and how, cohabitation has changed, we must reconcile two trends. On the one hand, most marriages are now preceded by cohabitation. Among first marriages formed in 1980–1984, only 41% were preceded by cohabitation, a rate that rose to 56% for marriages formed in 1990–1994 and to 66% for marriages formed in 2005–2009 (Manning, 2013), suggesting that cohabitation is now clearly institutionalized as part of the pathway to marriage (Cherlin, 2009). On the other hand, fewer cohabitations are transitioning to marriage (Bumpass & Lu, 2000), a pattern that implies a de-linking of marriage and cohabitation. In 1995, 58% of first cohabitations had transitioned to marriage within 3 years (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002), a rate that fell to 51% in 2002 (Goodwin, Mosher, & Chandra, 2010) and to 40% in 2006–2010 (Copen, Daniels, & Mosher, 2013). On the surface, these trends appear to be conflicting; that is, how can marriage be more strongly linked to cohabitation while cohabitation has become less strongly linked to marriage? On further inspection, though, they can largely be explained by the fact that marriage has become more selective and rare during the transition to adulthood, whereas cohabitation has not (Vespa & Painter, 2011).

Cohabitation Outcomes

Although cohabitation seems to play a larger role in the marriage process (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008), marriage is not always viewed as the inevitable goal or outcome of cohabitation (Manning & Smock, 2002), and this seems especially true among more recent cohorts and younger adults (Manning, Longmore, & Giordano, 2007). This is likely related to both attitudinal changes toward marriage (Cherlin, 2005) and broader economic changes affecting the affordability of marriage and altering the economic prerequisites and incentives for cohabitation and marriage (Lichter, Qian, & Mellott, 2006). Furthermore, the emergence of higher order cohabitations in recent cohorts (Lichter et al., 2010) suggests that more cohabitations are dissolving, for likely the same reasons. And although cohabiting unions are lasting longer, evidence suggests that most union transitions (dissolution or marriage) continue to occur within 2 years, with dissolution occurring a few months earlier, on average, than marriage (Copen et al., 2013). As such, overall, we would expect that recently formed cohabitations are more likely to dissolve and less likely to transition to marriage than those formed in earlier time periods. Thus, I posed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1A: Over time, cohabitation has become more likely to dissolve and less likely to transition to marriage.

Compositional Shifts in Cohabitation

Cohabitation has grown in prevalence and now occurs for individuals just beginning the transition to adulthood as well as those who have largely completed the transition (and, indeed, cohabitation increasingly occurs throughout the life course, even among middle-age and older adults (Brown, Lee, & Bulanda, 2006). As Schoen, Landale, and Daniels (2007) noted, there are a variety of paths to, and in, young adulthood, and unions formed during this period are often quite unstable. Men and women in their late teens and early 20s are rarely considering marriage, yet they often cohabit for economic reasons or convenience (Raley, Crissey, & Muller, 2007). Individuals in their mid- to late 20s and early 30s might be considering marriage and want to test their relationship before marriage (Johnson et al., 2002), whereas others may decide to cohabit upon getting engaged (Oppenheimer, 2003). It is not surprising, then, that there is a fairly straightforward association between age and cohabitation outcomes, with younger cohabitors more likely to experience dissolution and less likely to transition to marriage than their older counterparts (Guzzo, 2009). There are few racial/ethnic differences in the proportion of individuals who have ever cohabited, but there are large educational differences (Manning, 2013). Both socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity are associated with stability and outcomes, with members of racial/ethnic minority groups and individuals with less education at a higher risk of dissolution and Whites and better educated individuals more likely to marry (Rose-Greenland & Smock, 2013). To the extent that cohabitations increasingly comprise younger adults, individuals with less education, or racial/ethnic minorities—those with a higher risk of dissolution and a lower risk of marriage—these compositional shifts may be partially responsible for changes over time in outcomes.

Beyond socioeconomic and demographic differences in regard to who is cohabiting, though, are what appear to be key differences in the characteristics of the unions themselves. Rates of serial cohabitation, whereby individuals experience more than one cohabitation, increased nearly 40% over the late 1990s and early 2000s (Lichter et al., 2010). Relative to those with only one cohabitation, far fewer serial cohabitors reported themselves as engaged at the start of any of their cohabitations, they were less likely to have ever married, and they began cohabiting at fairly young ages (Cohen & Manning, 2010). The limited work on serial cohabitors suggests that, overall, those with more than one cohabitation are more disadvantaged than single-instance cohabitors (Cohen & Manning, 2010; Lichter et al., 2010). Cohabitations today are increasingly the setting of childbearing and rearing, too (Kennedy & Fitch, 2012; Lichter, 2012). Much of the rise in nonmarital fertility, for instance, is due to high levels of childbearing within cohabiting unions (Lichter, 2012). Many cohabitations also include children from prior relationships and are thus stepfamilies, accompanied by the elevated risk of instability seen among stepfamilies in general (Sweeney, 2010). Part of the decline in stability and transitions to marriage are also likely due to shifts in how cohabitors view their union’s future in terms of marriage. Although there is a strong positive association between being engaged at the start of cohabitation and subsequent marriage (Guzzo, 2009), there is evidence that these initial marital intentions are declining over time, in particular among individuals who have cohabited in the past (Vespa, 2014). Overall, this suggests substantial variation in the composition of individuals in cohabiting unions over time. As such, changes in cohabitation outcomes over time could be due to compositional differences among cohabitors, such as a growing proportion of cohabitations among those who are otherwise at high risk for dissolution and/or low risk for marriage (i.e., those in higher order unions or cohabiting stepfamilies). This led me to another prediction:

Hypothesis 1B: Changes in outcomes over time among cohabiting unions are attenuated when accounting for compositional shifts in socioeconomic and demographic characteristics among cohabiting individuals as well as shifts in cohabitation order, the presence of children, and marital intentions.

Changes in Intentions to Marry and Cohabitation Outcomes

If cohabitors have become decreasingly likely to begin their union with plans to marry, it is possible that the signaling function of engagement has changed. To the extent that cohabitation has become more socially acceptable, beginning a cohabitation with an engagement may have become an increasingly selective mechanism over time, occurring only among the most committed individuals and couples. Therefore, it may be that only individuals without initial marriage plans are exhibiting increased instability and declining chances of marriage over time, leading me to Hypothesis 2:

Hypothesis 2: Changes in the outcomes of cohabitations over time are more pronounced among individuals who are not engaged.

This study contributes to the existing knowledge about trends in cohabitation because I explicitly considered whether the apparent increase in instability and the decoupling of cohabitation and marriage are driven primarily by compositional shifts along two dimensions: (a) socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of individuals in cohabiting unions and (b) union-specific factors (marital intentions, cohabitation order, and the presence of children). Furthermore, by disaggregating unions by engagement, I examined whether shifts in outcomes are occurring even among individuals who are, ostensibly, the most committed to marriage. If compositional shifts among those in unions explain the changes in cohabitation outcomes, this implies that unions themselves have not become unstable and de-linked from marriage and thus there is no movement away from stable unions. Conversely, if cohabitations are actually becoming less stable and less likely to transition to marriage—even among people who explicitly planned to marry their cohabiting partner—this suggests aggregate social changes are destabilizing one of the most common unions Americans experience.

Method

In my analyses I pooled the 2002 and 2006–2010 cycles of the NSFG, a nationally representative cross-sectional household-based survey of men and women ages 15–44. The data are cross-sectional but contain a detailed retrospective relationship history of coresidential unions, and the NSFG surveys are designed to ensure comparability across cycles to provide time trend information. The sample includes 22,980 first and higher order cohabiting unions formed 1980 or later to 16,081 individuals age 15 or older at the start of cohabitation with valid information on start and end dates of unions; there were too few observed cohabitations prior to 1980 to include in the analyses. The analyses were restricted to those with valid engagement information (excluding 79 individuals); engagement status at the start of cohabitation was based on the following question, asked for each cohabitation: “At the time you began living together, were you and [partner] engaged to be married or did you have definite plans to get married?” Six cases were missing information on one of the control variables (nativity), bringing the potential sample size to 20,687 cohabitations among 15,336 individuals.

When weights are used to account for the complex sampling design, the NSFG samples are representative of the U.S. population at the time of the survey. It is important to note, though, that as we look back further in time, the sample is increasingly less representative of the national population at that time; that is, the 40- to 44-year-olds sampled in 2002 are representative of all 40- to 44-year-olds living in households in the United States in 2002 but may not be representative of 20- to 24-year-olds in 1982 if the population has changed substantially over the past few decades. Furthermore, the observed age range increases over time; in 2002, the NSFG observed men and women ages 15–44 from the 2002 cycle, but if one goes back to 1985, for example, one sees that individuals from this cycle of the data were observed only up to age 27. Similarly, individuals interviewed in 2008 were observed only through age 21 in 1985. Cohabitations formed several years prior to the date of the survey disproportionately comprise unions formed at the youngest ages and are thus accompanied by the well-established negative association between early age at union formation and subsequent stability (Guzzo, 2009; Tzeng & Mare, 1995), whereas cohabitations formed in the years immediately before the survey, when a broader age range was observed, are more representative. Because of the age selectivity in the sample, the analysis was further limited to the age groups for which there were a sufficient time series of observations and large sample sizes—individuals ages 18–34, disaggregated into four age groups: (a) 18–19 (n = 3,976), (b) 20–24 (n = 8,245 cohabitations), (c) 25–29 (n = 3,985 cohabitations), and (d) 30–34 (n = 1,684 cohabitations). These age restrictions produced a sample of 17,890 cohabitations to 13,107 individuals, comprising 86.1% of all observed premarital cohabitations formed after 1980 among individuals age 15–44 at the time of survey. To analyze change over time, I created six cohabitation cohorts: (a) 1980–1984, (b) 1985–1989, (c) 1990–1994, (d) 1995–1999, (e) 2000–2004, and (f) 2005 and later.

The independent variables were grouped into two categories: (a) socioeconomic and demographic characteristics and (b) union and fertility characteristics. The socioeconomic and demographic measures included age (18–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34), gender, race/ethnicity/nativity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, foreign-born Hispanic, native-born Hispanic, other), respondent’s mother’s education (less than high school or missing, high school degree, some college, college degree or higher), whether the respondent’s mother had a birth prior to age 18, a time-varying indicator of whether the respondent had a high school degree, and family structure at age 14 (both biological parents, stepfamily, other). Union and fertility characteristics included engagement status, cohabitation order, whether the respondent had any children born prior to cohabitation (dichotomously measured because few respondents had more than one child prior to cohabitation), and a time-varying measure of whether a child was born during cohabitation.

Analytical Approach

I first briefly describe the socioeconomic, demographic, and union-specific characteristics of the analytical sample of individuals in cohabiting unions by cohabitation cohort. I then show graphs from multiple-decrement life tables, which explored whether dissolution and marriage risks have changed over time and vary by engagement status; these graphs show the hazard curves within 36 months of starting cohabiting, because most cohabitations are no longer intact after this point (Goodwin et al., 2010). Because neither descriptive statistics nor life tables can simultaneously account for socioeconomic, demographic, and union factors, I used multivariate analyses to more thoroughly examine trends over time in cohabitation using event history models accounting for exposure and duration to examine outcomes. The data are converted into person-months, with exposure beginning the month that the cohabitation began and ending when the union dissolved, transitioned to marriage, or at the time of interview. The dependent variable included three categories indicating the union (a) was still intact, (b) had dissolved, or (c) had transitioned to marriage, and the analyses used multinomial logistic regression. The models included a control for union duration, specified as a time-varying piecewise nonlinear spline (< 6 months, 7–12 months, 13–24 months [omitted], 25–48 months, and 49 or more months), as the association between union transition and duration is nonlinear.

These analyses followed a two-pronged approach. First, I ran four nested models, with Model 1 including only controls for cohabitation cohort (and duration), Model 2 adding socioeconomic and demographic characteristics to Model 1, and Model 3 adding union and family characteristics to Model 1, with Model 4 as the full model. These nested models tested Hypotheses 1A and 1B, examining whether compositional differences explained any changes in outcomes over time. Second, to test Hypothesis 2, I ran models stratified by engagement to explore whether changes in outcomes were driven by respondents without marital intentions.

Results

Descriptive Cohabitation Characteristics

In Table 1 are displayed the socioeconomic, demographic, and union characteristics of the analytical sample of cohabiting unions across cohorts; readers should recall that the sample in general is not representative of all cohabiting unions during the specified time period. In the earliest cohorts, younger individuals were overrepresented because of the age structure of the NSFG; thus, the earliest cohorts were less representative of the overall population of cohabiting unions than later cohorts. As a result, it is not surprising that the proportion of cohabitations that were first cohabitations declined across cohorts. Similarly, the widening age range across cohorts likely contributed to the increasing proportion across cohorts of respondents with children at the start of the union, although the proportion who reported having children born during cohabitation stayed fairly stable, at about one-fifth of cohabitations. In the analytical sample there was no clear downward trend in the proportion of cohabitations that were begun with an engagement, hovering between 40% to 45% across cohorts. There were also differences across the cohorts in the distribution of cohabitors by race/ethnicity/nativity, education, and family structure during adolescence.

Table 1.

Weighted Percentages for the Descriptive Characteristics of Cohabitations Formed 1980–2010 Among Never-Married Individuals Ages 18–34 (N = 17,890 Cohabitations and 13,107 Individuals)

| Characteristics | 1980–1984 (n = 831) | 1985–1989 (n = 2,034) | 1990–1994 (n = 3,473) | 1995–1999 (n = 4,576) | 2000–2004 (n = 4,295) | 2005 or later (n = 2,681) | Total (N = 17,890) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic and demographic | |||||||

| Age group | |||||||

| 18–19 | 37.1 | 25.3 | 18.4 | 18.6 | 18.0 | 18.9 | 20.7 |

| 20–24 | 58.2 | 52.0 | 47.9 | 40.2 | 44.8 | 42.2 | 45.9 |

| 25–29 | 4.7 | 21.1 | 24.4 | 26.2 | 22.5 | 28.4 | 23.0 |

| 30–34 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 9.4 | 15.1 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 10.4 |

| Female | 48.9 | 52.1 | 53.5 | 51.8 | 51.4 | 48.1 | 51.5 |

| Race/ethnicity/nativity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.1 | 70.5 | 69.9 | 64.3 | 63.7 | 61.6 | 66.4 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.3 | 13.5 | 12.7 | 14.0 | 14.1 | 15.5 | 13.6 |

| Native-born Hispanic | 4.4 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 10.2 | 7.1 |

| Foreign-born Hispanic | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 6.9 | 7.1 |

| Other | 7.2 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.8 |

| High school grad at start | 72.1 | 73.4 | 74.8 | 73.7 | 73.5 | 72.1 | 73.6 |

| Mother’s education | |||||||

| Less than high school/missing | 26.4 | 26.8 | 22.9 | 21.9 | 20.6 | 18.5 | 22.5 |

| High school | 44.8 | 43.8 | 42.2 | 38.0 | 35.4 | 34.1 | 39.2 |

| Some college | 15.7 | 15.8 | 19.0 | 21.9 | 24.9 | 27.3 | 21.2 |

| College or more | 13.2 | 13.6 | 15.9 | 18.2 | 19.1 | 20.1 | 17.1 |

| Mother had teen birth | 16.6 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 16.5 | 15.0 | 15.1 | 16.1 |

| Family structure at age 14 | |||||||

| Both biological parents | 71.2 | 68.5 | 57.2 | 63.3 | 61.3 | 56.0 | 64.2 |

| Stepfamily | 9.8 | 10.4 | 11.6 | 12.5 | 12.6 | 13.2 | 11.9 |

| Other | 19.0 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 24.2 | 26.1 | 30.8 | 23.4 |

| Union/family characteristics | |||||||

| Cohabitation order | |||||||

| 1st cohabitation | 88.0 | 80.0 | 74.0 | 69.0 | 70.0 | 66.5 | 72.9 |

| 2nd cohabitation | 10.3 | 16.5 | 21.4 | 23.5 | 24.1 | 28.5 | 21.8 |

| 3rd or higher cohabitation | 1.7 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 5.3 |

| Engaged | 40.2 | 45.5 | 40.9 | 42.5 | 39.8 | 40.3 | 41.6 |

| Any children born prior to cohabitation | 2.9 | 6.6 | 7.8 | 12.1 | 15.3 | 19.1 | 11.2 |

| Had child while cohabiting | 17.1 | 19.2 | 20.4 | 21.6 | 19.1 | 14.2 | 19.4 |

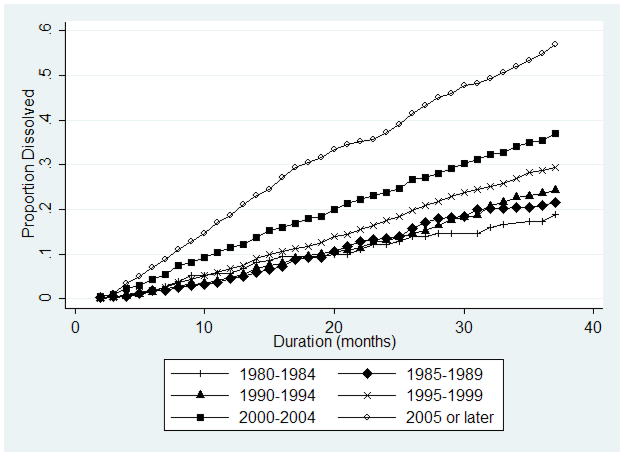

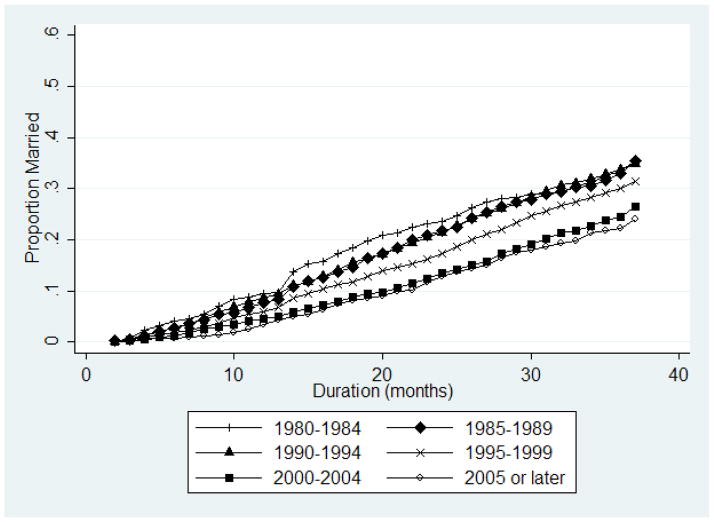

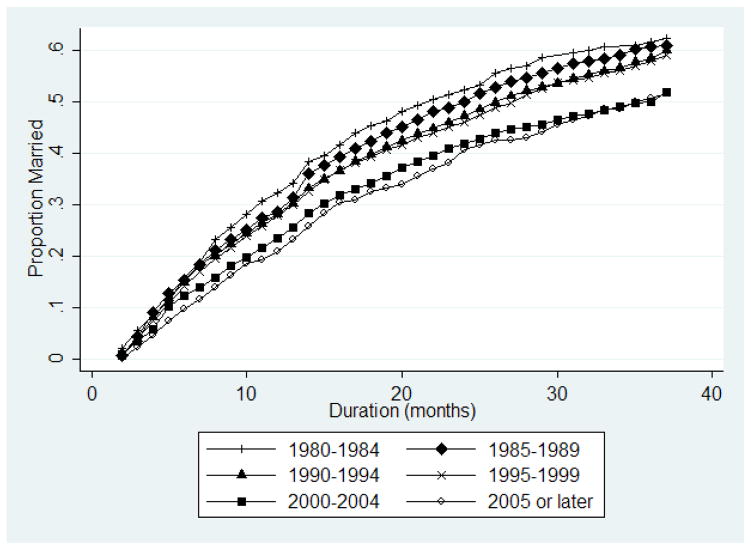

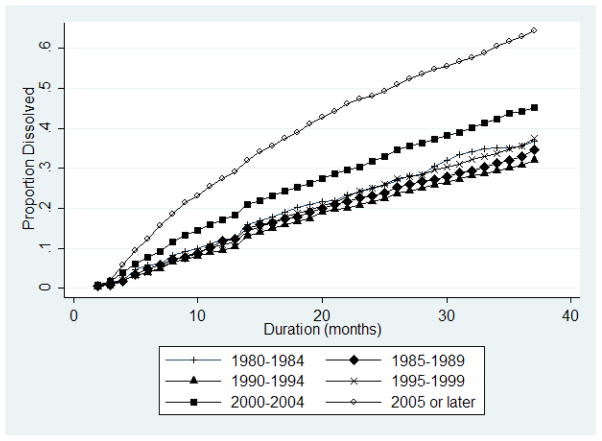

In Figures 1 through 4 I present hazard curves for the first 36 months of cohabitation by engagement status, looking at the risk of dissolution and the risk of marriage over time. As would be expected, dissolution risks were higher, and marriage risks lower, for engaged respondents compared to those who were not engaged at the start of cohabitation. This is neither surprising nor new. What is interesting, though, are the differences across cohabitation cohorts. Looking first at dissolution risks among the engaged, the first few cohorts—cohabitations formed in the 1980s and the early 1990s—were tightly clustered and largely exhibited the same general increase over time in the risk of dissolution. By the late 1990s, dissolution risks were noticeably higher at longer durations than the earlier cohorts. But the cohabitations formed after 2000 really stand out: Unions formed between 2000 and 2004 faced much higher dissolution risks at every duration compared to the earlier cohorts of cohabitations, and the cohabitations formed after 2005 were even more at risk of dissolution. The elevated risk of dissolution for more recent cohorts were also present for the non-engaged, although the level of risk was higher at every duration than for the engaged, and unions formed in the late 1990s were not noticeably different than those in the 1980s and early 1990s. The trends across cohorts were even more stark when one considers that the youngest age groups were overrepresented in the early cohorts. As such, the observed dissolution risks for the earlier cohorts were almost certainly overestimated, given that younger individuals are more likely to experience union dissolution (Guzzo, 2009; Tzeng & Mare, 1995). If the earliest cohorts had a more representative age distribution, the dissolution risks would likely have been lower, making the changes across cohorts more dramatic.

Figure 1.

Dissolution Within 36 Months, Engaged.

Figure 4.

Marriage Within 36 Months, Not Engaged.

In regard to marriage, the risks across cohorts were more tightly clustered and exhibited less variation over time compared to dissolution risks, and at every duration the risk of marriage was lower among the non-engaged respondents. Still, there were some appreciable differences across cohorts. Each successively more recent cohabitation cohort was less likely to transition to marriage through the early 1990s for engaged cohabitors, with minimal differences between cohabitations formed in the early and late 1990s. As with dissolution, more recent cohabitations stand out. There appeared to be a sharp decline in the risk of marriage between cohabitations formed prior to 2000 and those formed after 2000. By the end of the 36 months of duration shown here, there was a difference of roughly 10 percentage points in the proportion married among cohabitations formed prior to 2000 and those formed after 2000. For those who were not engaged at the start of cohabitation, risks were slightly less clustered together, but the same overall trends were present. The declining risk of marriage started with the 1995–1999 cohort but was still stronger for the 2000–2004 and 2005 and later cohabitation cohorts. Also, as before, because of the overrepresentation of younger adults in the earliest cohorts, who are less likely to marry than older cohabitors (Guzzo, 2009), the decline in marriage risks across cohorts was likely understated. Thus, there is support for Hypothesis 1A, that cohabitation outcomes have changed over time, with the increase in dissolution seemingly larger than the decrease in marriage.

Overall, then, although the hazard curves demonstrate increasing dissolution and decreasing marriage among cohabiting unions over time, the descriptive characteristics shown in Table 1 reveal that the analytical sample varied substantially across a range of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics as well as union and fertility indicators across cohorts. Thus, I turned to multivariate analyses to examine changes over time more thoroughly.

Predicting Outcomes Across Cohorts

The nested models for cohabitations among never-married men and women age 18–34 are presented in Table 2. These models tested Hypotheses 1A and 1B, which are competing hypotheses, and show the relative risk ratios (RRRs) in a series of nested models designed to demonstrate the extent to which compositional differences among those in unions contribute to changes in union stability and outcomes over time. Model 1 was a baseline model, including only cohort (1990–1994 as the reference category) and duration controls. Model 2 added socioeconomic and demographic factors to the baseline model, and Model 3 added union and fertility characteristics to the baseline model, with Model 4 containing the full set of covariates. The baseline model in Model 1 supported Hypothesis 1A: Cohabitations formed in later years were more likely to dissolve and less likely to transition to marriage than remain intact relative to cohabitations formed in 1990–1994, and the magnitude of the RRRs increased across cohorts, suggesting that cohabitations have become increasingly unstable and less connected to marriage over time. Relative to cohabitations formed between 1990 and 1994, cohabitations formed from 1995–1999, 2000–2004, and 2005 and later were 13%, 49%, and 87%, respectively, more likely to dissolve than remain intact. The lower risk of marriage over remaining intact occurred only for the last two cohabitation cohorts (2000–2004 and 2005 and later), which were about 18% and 31% less likely to marry than remain intact, respectively. Although Hypothesis 1A was largely supported, there was some evidence that the earliest cohort of cohabitations were also unstable; cohabitations formed in 1980–1984 were about 20% more likely to dissolve than remain intact compared to cohabitations formed a decade later. Duration largely worked as would be expected; cohabitations of 6 or fewer months were less likely to dissolve or transition to marriage than those 13–24 months in duration, with no differences between 7–12 months and 13–24 months. Cohabitations greater than 2 years in duration were less likely to either dissolve or marry, and the longer a cohabiting union lasted, the more likely it was to remain intact as a cohabiting union.

Table 2.

Relative Risk Ratios From Multinomial Logistic Regression of Cohabitation Outcomes Among Never-Married Adults Ages 18–34

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved vs. intact | Married vs. intact | Dissolved vs. intact | Married vs. intact | Dissolved vs. intact | Married vs. intact | Dissolved vs. intact | Married vs. intact | |

| Cohort (ref.: 1990–1994) | ||||||||

| 1980–1984 | 1.23* | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.27** | 1.19† | 1.20† | 1.10 | 1.28** |

| 1985–1989 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.13* | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.08 |

| 1995–1999 | 1.13* | 0.98 | 1.14* | 0.99 | 1.16* | 0.99 | 1.15* | 0.99 |

| 2000–2004 | 1.49*** | 0.82*** | 1.48*** | 0.84*** | 1.53*** | 0.83*** | 1.50*** | 0.84** |

| 2005 or later | 1.87*** | 0.69*** | 1.85*** | 0.70*** | 1.94*** | 0.70*** | 1.89*** | 0.69** |

| Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Age group (ref.: 25–29) | ||||||||

| 18–19 | 1.55*** | 0.64*** | 1.52*** | 0.64*** | ||||

| 20–24 | 1.36*** | 0.80*** | 1.35*** | 0.80*** | ||||

| 30–34 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.97 | ||||

| Female | 0.99 | 0.93* | 0.98 | 0.95 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity/nativity (ref.: non-Hispanic White | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.08 | 0.56*** | 1.17** | 0.51*** | ||||

| Native-born Hispanic | 0.92 | 0.62*** | 0.98 | 0.60*** | ||||

| Foreign-born Hispanic | 0.41*** | 0.58*** | 0.45*** | 0.53*** | ||||

| Other | 0.88 | 0.77* | 0.91 | 0.75*** | ||||

| High school graduate | 1.01 | 1.40*** | 0.99 | 1.35*** | ||||

| Mother’s education (ref.: high school) | ||||||||

| Less than high school/missing | 0.93 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 1.00 | ||||

| Some college | 1.18*** | 1.07 | 1.16** | 1.06 | ||||

| College or more | 1.23*** | 1.03 | 1.18** | 1.09 | ||||

| Mother had teen birth | 1.01 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.99 | ||||

| Family structure at age 14 (ref.: both biological parents) | ||||||||

| Stepfamily | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.01 | 0.92 | ||||

| Other | 1.03 | 0.79*** | 1.02 | 0.85*** | ||||

| Union/family characteristics | ||||||||

| Cohabitation order | ||||||||

| 1st cohabitation | 1.38*** | 0.86*** | 1.27*** | 0.94 | ||||

| 2nd cohabitation | — | — | — | — | ||||

| 3rd or higher cohabitation | 1.41*** | 0.99 | 1.49*** | 0.96 | ||||

| Engaged | 0.59*** | 2.34*** | 0.61*** | 2.47*** | ||||

| Any children born prior to cohabitation | 1.00 | 0.61*** | 1.09 | 0.74*** | ||||

| Had child while cohabiting | 0.72*** | 0.57*** | 0.79*** | 0.79*** | ||||

| Duration (ref.: 13–24 months) | ||||||||

| 6 months or less | 0.82** | 0.84* | 0.81*** | 0.81*** | 0.80* | 0.74*** | 0.81*** | 0.73*** |

| 7–12 months | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.89† | 0.95 | 0.85** | 0.95 | 0.84** |

| 25–48 months | 0.87* | 0.78** | 0.89* | 0.82*** | 0.91† | 0.86** | 0.91† | 0.87* |

| 49 or more months | 0.65*** | 0.43*** | 0.73*** | 0.51*** | 0.74*** | 0.54*** | 0.78*** | 0.57*** |

| Constant | 0.01*** | 0.02*** | 0.01*** | 0.03*** | 0.01*** | 0.02*** | 0.09*** | 0.02*** |

Note: Person-months = 541,062; number of cohabitations = 17,890. ref. = reference category.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Model 2 added in socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. As shown in Table 1, compared to cohabitations formed in earlier time periods in the analytical sample, more recent cohabitation cohorts included more individuals in their late 20s and early 30s, more non-White individuals, and more individuals who grew up in non-intact families but had more educated mothers. This model tested whether these compositional differences account for shifts in dissolution and marriage risks over time (Hypothesis 1B), and the short answer is that they do not. Although socioeconomic and demographic characteristics were associated with cohabitation outcomes, they did not explain the association with cohabitation cohort and outcomes; in fact, a positive association with marriage and early cohorts emerged. Changes in the risk of dissolution relative to remaining intact were largely the same, with cohabitations formed from 1995 onward increasingly likely to dissolve. Cohabitations formed in the early 1980s were no longer more likely to dissolve than those formed in the early 1990s, largely because of the presence of the control for age, given the overrepresentation of the very young in the early cohorts. In the presence of socioeconomic and demographic controls, cohabiting unions formed in 1980–1984 were 27% more likely, and unions formed in 1985–1989 were 13% more likely, to transition to marriage than remain intact relative to cohabitations formed in 1990–1994. Cohabitations formed in the late 1990s were not significantly different in the risk of marriage relative to those formed in the early 1990s, but those formed after 2000 were decreasingly likely to end in marriage, with a similar magnitude as seen in Model 1.

Although the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics did not account for the association between cohort and outcomes, they were significantly associated with outcomes in their own right. Younger cohabitors were more likely to experience dissolution and less likely to marry than those age 25–29, although those in their early 30s did not significantly differ from those in their late 20s. Women were slightly less likely to marry than remain cohabiting relative to men (RRR = 0.93). There were few racial/ethnic differences in dissolution risks, although foreign-born Hispanics were less likely to experience dissolution than Whites (RRR = 0.41). However, compared to Whites, all groups were less likely to transition to marriage than remain cohabiting; Blacks and Hispanics were about 40% less likely to marry than Whites, whereas those in the “other” category were about 25% less likely. Individuals whose mother had at least some college were more likely to dissolve their cohabiting unions relative to those with a high school degree, and those who lived in an “other” family type (primarily those in single-parent families) were about 20% less likely to marry over remaining in an intact cohabitation compared to their peers who lived with both biological parents at age 14. As with cohabitation cohort, the effects of duration changed only slightly with the inclusion of socioeconomic and demographic controls.

In Model 3, changes in the characteristics of cohabiting unions in terms of engagement, cohabitation order, and fertility were investigated as potential factors which may explain cohort differences in dissolution and marriage (Hypothesis 1B). Again, however, accounting for compositional shifts among the characteristics of the union did not attenuate the association between the time period in which a cohabitation was formed and its risk of dissolution or marriage, even though these factors were significantly and directly associated with cohabiting outcomes. Cohabitations formed after 1995 were still increasingly likely to dissolve relative to those formed between 1990–1994, and unions formed after 2000 remained decreasingly likely to transition to marriage. Unions formed in 1980–1984 were both more likely to dissolve and more likely to marry than those formed in 1990–1994, but the differences were only marginally significant.

The characteristics of the cohabiting union, however, were significant, as expected. First cohabitations differed from second cohabitations, being both more likely to dissolve (RRR = 1.38) and less likely to end in marriage (RRR = 0.86). Third cohabitations were about 40% more likely to dissolve than second cohabitations but did not differ in the risk of marriage (in fact, first and third cohabitations did not differ from each other, results not shown). Engagement was particularly important, as expected: Respondents who report being engaged or having marriage plans at the start of cohabitation were less likely to dissolve (RRR = 0.59) and substantially more likely to marry (RRR = 2.34) than their non-engaged counterparts. Cohabitors who had children prior to the union did not have higher risks of dissolution than those who were childless, but they were about 40% less likely to transition to marriage. Having a child during cohabitation reduced both dissolution and marriage risks. The association between duration and outcomes changed slightly with the inclusion of characteristics of the cohabiting union. Cohabitations between 2 and 4 years’ duration became only marginally less likely to dissolve than those between 1 and 2 years’ duration. Cohabitations of 6 months or less became even less likely to transition to marriage (moving from about 15% less likely to 25% less likely from Model 1 to Model 3), and cohabitations of 7–12 months became significantly less likely to transition to marriage as well (RRR = 0.85). Cohabitations of longer durations were still less likely to marry as well, but the magnitude of longer durations diminished in effect.

The last two columns of Table 2 present the full model, adding in both socioeconomic and demographic characteristics as well as characteristics of the cohabiting union. In the presence of all the covariates, cohabitation cohort remained a significant predictor of dissolution and marriage. Compared to unions formed in the early 1990s, cohabitations formed after 1995 were increasingly likely to dissolve. Cohabitations formed after 2000 were decreasingly likely to marry; conversely, a cohabiting union formed in the early 1980s was more likely to end in marriage than one formed in the early 1990s. Including various controls, though often significant in their own right, did little to change the magnitude of the cohort relative risk ratio. As such, Hypothesis 1A was supported, and Hypothesis 1B was rejected. The association between cohabitation outcomes and socioeconomic, demographic, and union characteristics changed little from Models 2 and 3 to Model 4. In the presence of controls for cohabitation characteristics, Blacks were more likely to experience dissolution than whites (RRR = 1.17), and women were no longer less likely to marry than men. In the presence of socioeconomic and demographic covariates there were no differences across cohabitation order in the risk of marriage, although first and third cohabitations remained more likely to dissolve than second cohabitations. The association between engagement and marriage strengthened slightly, and the negative association between children born prior to or during cohabitation and marriage risk diminished somewhat. The association between duration and outcomes did not change.

The above results confirm that cohabiting unions were increasingly unstable and disconnected from marriage over time. However, given some evidence that cohabitations were decreasingly likely to start with plans to marry (Vespa, 2014) combined with the findings here indicating that engagement was the biggest predictor of marriage, I tested whether the observed cohort differences masked differences across initial marriage plans (Hypothesis 2); that is, increasing instability and decreasing marital transitions over time may be concentrated among individuals without marriage plans, to the extent that marriage plans are increasingly selective of those who are committed to marriage. These analyses are shown in Table 3, in which Model 4 from Table 2 was re-run but with the results stratified by engagement status. Only the RRRs for cohort are included in this table, but the full models are available on request. These results did not support Hypothesis 2, that the observed changes in cohabiting outcomes over time are concentrated among those without marriage plans. Both engaged and non-engaged respondents had a higher risk of dissolution and a lower risk of marriage for cohabitations formed after 2000 relative to those formed in 1990–1994. Engaged cohabitations formed after 2005 had a particularly high risk of instability (RRR = 2.27), but Chow tests (not shown) that compared the coefficients across models did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the engaged and non-engaged in the cohort RRRs.

Discussion

Cohabitation has become quite common in the United States in recent decades, given that most people will cohabit outside of marriage at some point in their lives. The majority of today’s marriages are preceded by cohabitation even as fewer cohabitations are transitioning to marriage (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008) and marriage rates are declining (CDC/NCHS National Vital Statistics System, 2012). In this research I examined whether compositional shifts in the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of individuals in cohabiting unions, along with shifts in the characteristics of unions themselves (in terms of cohabitation order, engagement, and the presence of children), are partly responsible for observed changes in the outcomes of cohabitation over time. In general, I found support for the notion that cohabitation is indeed changing over time, as suggested in Hypothesis 1A. Since the late 1990s, the risk of dissolution has increased, with the most pronounced changes occurring for cohabitations formed most recently. The chances of marriage, too, have declined over time, with the earliest unions—those formed in the 1980s—more likely to transition to marriage and those formed since 2000 less likely to transition to marriage. Thus, the shifts in the outcomes of cohabiting unions have been strongest for the most recent cohorts of cohabitors, with less variation across cohabitations formed during the 1980s and early 1990s. In fact, the truncated age structure of the analytical sample means those most at risk of dissolution and least likely to marry are overrepresented in the earliest cohorts, which implies that the observed differences across cohorts are underestimated and thus the increased dissolution risks and decreased marriage risks over time are even greater. The elevated risk of dissolution seems to plays particularly big role in changes in cohabiting outcomes over the past few decades, whereas the changes in the risk of marriage have been smaller (but still significant). Although compositional shifts have indeed occurred, neither shifts in the socioeconomic and demographic profile of respondents in cohabiting unions nor shifts in the characteristics of unions account for the increased instability and declining risks of marriage in later cohorts, as suggested in Hypothesis 1B.

Furthermore, there is no evidence that increasing dissolution and decreasing marriage reflect declines in commitment at the start of cohabiting unions. Contrary to Hypothesis 2, the association between engagement and the outcomes of cohabiting unions does not seem to differ over time. As such, to the extent that engagement at the start of cohabitation is becoming more rare (Vespa, 2014), it is not becoming more selective of individuals whose unions will be more stable and more likely to transition to marriage, contrary to expectations. Engagement itself, though, remains strongly related to stability and marriage, as seen in other work (Guzzo, 2009).

Together, these findings add further evidence to the de-linking of cohabitation and marriage. Marriage is becoming, across the board, a more selective institution, in terms of who marries (and who marries directly), who benefits, and who stays married, among other factors (Lee & Payne, 2010; Kennedy & Ruggles,2014). Marriage rates are at an all-time low (Cruz, 2013). At the same time, cohabitation is on the rise and shows no signs of abating (Manning, 2013), and although many cohabitors enter their unions with plans to marry, a substantial proportion enter without explicit plans or expectations regarding marriage, often driven by financial and logistical concerns (Sassler, 2004; Smock, Manning, & Porter, 2005). Thus, even as marriage is becoming more selective, cohabitation is becoming less so. The declining selectivity of cohabitation, driven perhaps by a “lowering of the bar” to cohabit as cohabitation becomes increasingly acceptable (Popenoe, 2005; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001), likely contributes to the rising instability of cohabiting unions. As I suggested at the start of this article, then, the present results confirm the notion that marriage has become less a part of the cohabitation process over time.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to keep in mind. First, in this research, individuals in cohabiting unions, not individuals or cohabiting unions themselves, were used as the unit of analysis. Therefore, it cannot inform us about changes in individual union formation behavior over time and did not analyze trends in the likelihood of entering different types of unions. Second, the NSFG samples individuals, not cohabitations, so the cohabitations are not necessarily representative of all cohabitations but instead of the cohabiting unions of individuals ages 15–44 in 2002 and in 2006–2010. To limit the extent to which this affected the analysis, I restricted the sample by age, but this likely still affected generalizability to some degree. In particular, the earliest cohorts were disproportionately composed of younger adults, who in general exhibit higher union instability and lower chances of marriage (Guzzo, 2009; Tzeng & Mare, 1995). Third, some research suggests that short-term cohabitations are more likely to be underreported for cohabitations that occurred in periods more distal to the survey than for more recent unions (Hayford & Morgan, 2008). Qualitative evidence also shows that the exact start and end dates of cohabitation are often quite fluid (Manning & Smock, 2005), as is the accuracy of retrospective reports (Teitler, Reichman, & Koball, 2006). To the extent that retrospective recall issues might favor more well-defined and stable unions, then the results could overstate differences in cohabitation outcomes over time. However, if this were true, we would also expect that there would be more non-engaged cohabitations in recent cohorts, and there is no evidence that is occurring. Fourth, the measure of engagement was not ideal; the phrases “engaged to be married” and “definite plans to marry” are somewhat vague, and it is possible that engagement is subject to recall bias—that respondents whose relationship was intact were more likely to report their cohabitation as beginning with engagement or definite plans to marry as opposed to those who were engaged being more likely to have an intact relationship.

Conclusion

The compositional shifts of individuals in cohabiting unions over time reflect the growing diversity of the American population and the shifting role of cohabitation in the family landscape, clearly demonstrating that today’s cohabitations are not the same as those in the past. A growing proportion of cohabitors are likely those for whom dissolution risks are higher and marriage chances are lower: younger adults, those with children from a past union, those in higher order unions, and so on. As such, it would seem that part of the increase in cohabiting instability and decrease in transitions to marriage is compositional. In this study, however, I found little evidence that compositional shifts among individuals in cohabiting unions are primarily responsible for changes in outcomes, because cohort differences were found even after accounting for compositional shifts and even among respondents who reported that when they started living together they planned to marry their cohabiting partner. This suggests that other factors have contributed to increased instability and a weakening of the link between cohabitation and marriage.

Given that the analytical sample contained never-married young adults and that the differences were most pronounced for cohabitations formed since 2000, the results here may reflect the well-documented difficulties today’s young men and women are experiencing in the transition to adulthood (Settersten & Ray, 2010). Although the social and economic prerequisites for marriage have increased (Cherlin, 2005), Americans remain pro-marriage, and the majority of never-married men and women indicate they want to marry in the future (Manning et al., 2007; Pew Research Center, 2010; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001). These results—that cohabiting unions, even those begun with engagement, are more likely to dissolve and less likely to transition to marriage over time even after accounting for compositional shifts—is all the more troubling because it suggests that young adults are having trouble realizing their desires and intentions to form more permanent and stable unions, particularly marriages. For today’s young adults, achieving career and economic stability may be a real barrier to union stability and marriage (Smock et al., 2005).

Attitudinal changes toward union formation and stability cannot be ruled out either. Today’s young adults may simply view cohabitation differently than earlier cohorts. Cohabitations may be increasingly viewed as a matter of convenience and comfort—that is, as a way to be with one’s partner and simultaneously minimize economic and logistic costs (Sassler, 2004)—rather than as part of a relationship progression toward marriage. Pressures to marry one’s partner, too, may be declining, if the bar for marriage (emotionally, physically, and/or economically) is getting higher, such that people are increasingly likely to think it is better to end a cohabiting union (and an engagement) prior to marriage than to risk marrying and subsequently divorcing. Thus, it seems that cohabitation in the United States, at least among never-married young adults, remains best characterized as an alternative to being single.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the increased instability of cohabiting unions is likely responsible, in part, for the fairly stable divorce rate seen since the 1980s (Kennedy & Ruggles, 2014). One could argue that the dissolution of a cohabiting union is, in many ways, an averted divorce, to the extent that in earlier time periods the same couple would have married directly but experienced the same relationship problems that led to marital dissolution. If this is the case, then rising instability and the de-linking of cohabitation and marriage is not necessarily problematic. Conversely, if many of today’s cohabitations are just a variation of formal marriage—involving children, financial commitments, and so on—then rising rates of instability do indeed suggest some sort of large-scale issue affecting today’s unions, making more conventional measures of union formation and stability less meaningful (Kennedy & Ruggles, 2014).

Figure 2.

Marriage Within 36 Months, Engaged.

Figure 3.

Dissolution Within 36 Months, Not Engaged.

Table 3.

Relative Risk Ratios From Multinomial Logistic Regression of Cohabitation Outcomes Among Never-Married Adults Ages 18–34, Disaggregated by Engagement Status

| Predictor | Engageda | Not engagedb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved vs. intact | Married vs. intact | Dissolved vs. intact | Married vs. intact | |

| Cohort (ref.: 1990–1994) | ||||

| 1980–1984 | 0.82 | 1.36*** | 1.17 | 1.21 |

| 1985–1989 | 0.88 | 1.14† | 1.10 | 1.07 |

| 1995–1999 | 1.16 | 1.04 | 1.15† | 0.95 |

| 2000–2004 | 1.43* | 0.89† | 1.52*** | 0.76*** |

| 2005 or later | 2.27*** | 0.70*** | 1.76*** | 0.69** |

| Constant | 0.01*** | 0.04*** | 0.01*** | 0.03*** |

Note: Models control for age, gender, race/ethnicity/nativity, high school education, mother’s education, mother had a teen birth, family structure at age 14, cohabitation order, children born prior to cohabitation, children born during cohabitation, and duration. ref. = reference category.

Person-months = 198,963, number of cohabitations = 7,215.

Person-months = 342,099, number of cohabitations = 10,675.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Center for Family and Demographic Research at Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant R24HD050959-09).

Footnotes

An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2011 annual conference of the National Council on Family Relations, Orlando, FL.

References

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 23. 22. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_022.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL. Union transitions among cohabitors: The significance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:833–846. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Lee GR, Bulanda JR. Cohabitation among older adults: A national portrait. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61:S71–S79. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.s71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass L, Lu HH. Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies. 2000;54:29–41. doi: 10.1080/713779060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC/NCHS National Vital Statistics System. National marriage and divorce rates and trends. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/marriage_divorce_tables.htm.

- Chandra A, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Abma JC, Jones J. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 23. 25. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2005. Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of U.S. women: Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_025.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. American marriage in the early twenty-first century. The Future of Children. 2005;15:33–55. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. The marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and the family in America today. New York: Knopf; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Manning W. The relationship context of premarital serial cohabitation. Social Science Research. 2010;39:766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copen CE, Daniels K, Mosher WD. National Health Statistics Reports. 64. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. First premarital cohabitation in the United States: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz J. Marriage: More than a century of change. Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University; Bowling Green, OH: 2013. Family Profile FP-13-13. [Google Scholar]

- Hayford SR, Morgan SP. The quality of retrospective data on cohabitation. Demography. 2008;45:129–141. doi: 10.1353/dem.2008.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P, Timberlake JM. The role of cohabitation in family formation: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:1214–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin PY, Mosher WD, Chandra A. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 23. 25. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. Marriage and cohabitation in the United States: A statistical portrait based on Cycle 6 (2002) of the National Survey of Family Growth. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_028.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB. The relationship between life course events and union formation. Social Science Research. 2006;35:384–408. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB. Marital intentions and the stability of first cohabitations. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30:179–205. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CA, Stanley SM, Glenn ND, Amato PR, Nock SL, Markman HJ, Dion MR. Marriage in Oklahoma: 2001 baseline statewide survey on marriage and divorce. Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Department of Human Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura S. Median age at first marriage in the US, 2008. Center for Marriage & Family Research, Bowling Green State University; Bowling Green, OH: 2009. Family Profile FP-09-03. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Bumpass L. Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research. 2008;19:1663–1692. doi: 10.4054/demres.2008.19.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Fitch CA. Measuring cohabitation and family structure in the United States: Assessing the impact of new data from the Current Population Survey. Demography. 2012;49:1479–1498. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0126-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Ruggles S. Breaking up is hard to count: The rise of divorce in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography. 2014;51:587–598. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0270-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GL, Payne KK. Changing marriage patterns since 1970: What’s going on, and why? Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2010;41:537–555. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT. Childbearing among cohabiting women: Race, pregnancy, and union transitions. In: Booth A, Brown SL, Landale NS, Manning WD, McHale SM, editors. Early adulthood in a family context. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Qian Z, Mellott LM. Marriage or dissolution? Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography. 2006;43:223–240. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Turner RN, Sassler S. National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation. Social Science Research. 2010;39:754–765. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD. Trends in cohabitation: Over twenty years of change, 1987–2010. Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University; Bowling Green, OH: 2013. Family Profile FP-13-12. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Longmore MA, Giordano PC. The changing institution of marriage: Adolescents’ expectations to cohabit and to marry. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:559–575. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ. First comes cohabitation and then comes marriage? A research note. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:1065–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ. Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Cohabiting and marriage during young men’s career development process. Demography. 2003;40:127–149. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The decline of marriage and the rise of new families. Washington, DC: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Popenoe D. The state of unions 2005: The social health of marriage in America. Piscataway, NJ: National Marriage Project; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK. Recent trends and differentials in marriage and cohabitation: The United States. In: Waite LJ, editor. The ties that bind: Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2000. pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK. Increasing fertility in cohabiting unions: Evidence for the Second Demographic Transition in the United States? Demography. 2001;38:59–66. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Crissey S, Muller C. Of sex and romance: Late adolescent relationships and young adult union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1210–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Greenland F, Smock PJ. Living together unmarried: What do we know about cohabiting families? In: Peterson GW, Bush KR, editors. Handbook of marriage and family. 3. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S. The process of entering into cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen R, Landale NS, Daniels K. Family transitions in young adulthood. Demography. 2007;44:807–820. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA, Jr, Ray B. What’s going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. The Future of Children. 2010;20:19–41. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ. Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, Porter M. “Everything’s there except money”: How money shapes decisions to marry among cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:680–696. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney M. Remarriage and stepfamilies: Strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:667–684. [Google Scholar]

- Teitler JO, Reichman NE, Koball H. Contemporaneous versus retrospective reports of cohabitation in the Fragile Families survey. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:469–477. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Young-DeMarco L. Four decades of trends in attitudes toward family issues in the United States: The 1960s through the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1009–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng JM, Mare RD. Labor market and socioeconomic effects on marital stability. Social Science Research. 1995;24:329–351. [Google Scholar]

- Vespa J. Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014;76:207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Vespa J, Painter MA., II Cohabitation history, marriage, and wealth accumulation. Demography. 2011;48:983–1004. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]