Abstract

Background and Aims

Gambling and gaming activities have become increasingly recognised as sharing many common features at a structural and aesthetic level. Both have also been implicated as contributing to harm through excessive involvement. Despite this, relatively little attention has been given to the fundamental characteristics that differentiate these two classes of activity, especially in situations where the boundaries between them may be particularly hard to distinguish. This is evident, for example, in digital games that incorporate free and paid virtual currencies or items, as well as the capacity for wagering. Such overlaps create problems for regulatory classifications, screening, diagnosis and treatment. Is the problem related to the gambling or gaming content?

Methods

In this paper, we review the principal sources of overlap between the activity classes in terms of several dimensions: interactivity, monetisation, betting and wagering, types of outcomes, structural fidelity, context and centrality of content, and advertising.

Results

We argue that gaming is principally defined by its interactivity, skill-based play, and contextual indicators of progression and success. In contrast, gambling is defined by betting and wagering mechanics, predominantly chance-determined outcomes, and monetisation features that involve risk and payout to the player. A checklist measure is provided, with practical examples, to examine activities according to features of design and function, which may inform guidelines for policy makers, researchers and treatment providers.

Discussion and conclusions

We suggest that, in some instances, using category-based nomenclature (e.g., “gambling-like game”) may be too vague or cumbersome to adequately organise our understanding of new gaming/gambling hybrid activities.

Keywords: gambling, gaming, convergence, structural features, behavioural addictions

Introduction

Gaming and gambling activities and industries are changing constantly. This has been largely driven by increasing technological capabilities that afford users a greater ability to access online activities with ease and affordability. One consequence of the rapid advent and uptake of digital technologies has been the capacity for digital media content and functionality previously available only on a singular device to now span, influence, and to be shared across multiple devices and networks. Sometimes referred to as ‘digital convergence’ (Griffiths, 2013; King, Delfabbro & Griffiths, 2010), this phenomenon has also been observed in the crossover of some gambling and gaming products, platforms, and networks. These developments have led to growing concerns that the structural boundaries between gaming and gambling may potentially become indistinguishable, such that ‘hybrid’ gambling activities adopt features of gaming (and vice-versa) (King & Delfabbro, 2016). This overlap is compounded by the fact that some gambling activities, such as electronic gambling machines, are already internally referred to and publicly promoted as ‘gaming’ by the gambling industry, a discursive shift toward emphasizing the ‘entertainment’ component of gambling. The convergence of gaming and gambling is particularly notable in the rise of ‘social casino games’ (e.g., Zynga Poker, DoubleDown Casino) that feature on online social networking sites and as apps on smartphones. These games simulate many features and opportunities within gambling activities, such as card games and electronic gaming machines, while also providing the option for players to spend money in order to play. The aim of this review was to discuss the key features of gaming and gambling, and their overlap, to promote further critical discussion of the terminology employed across a diverse range of technology-based addictive behaviours.

Convergence of Gaming and Gambling

Psychological research suggests that there are increasing opportunities for digital gambling and gambling-themed games and activities (Gainsbury, Russell & Hing, 2014; King, Delfabbro, Kaptsis & Zwaans, 2014). However, such research provides only a limited analysis of the scope and types of activities, opportunities, and promotions associated with convergence. This may be attributed to academics’ relative lack of access to up-to-date information on the market and gambling/gaming intellectual property (as well as time lag in publication); the changing nature of the market; difficulties associated with asking research participants to recognise, recall, and report a wide range of activities; and, experiences for which there may be no established consensus on terminology (Gainsbury, Hing, Delfabbro & King, 2014). Industry reports can provide a useful resource to fill this gap in the knowledge base. For example, a recent Morgan Stanley Research report (2012) stated there are five primary types of convergence between gambling and gaming: (1) the introduction of gambling elements to games on social media; (2) the cross-selling and marketing of online gambling sites or land-based venues to social gaming customers; (3) the introduction of social gaming features to online gambling sites; (4) the consolidation of similar games on non-monetary social gaming and online gambling sites owned by the same operator; and (5) the ‘gamblification’ of non-gambling games, in which customers can win items of value. These types of convergence between gambling and gaming suggest that there is significant potential for new products to be developed and introduced in the market, and therefore a range of different activities for which vulnerable individuals may develop problematic habits of play.

Practical Problems for Addiction Research

One conceptual dilemma in addiction research is that two activities, each referred to as a ‘game’, may have very different structural properties that offer different playing experiences. Similarly, some activities referred to as games may in fact have more in common with gambling. It was recently acknowledged that, in developing the diagnostic guidelines for Internet gaming disorder in the DSM-5, there were limitations in terminology that prevented adequate encapsulation of those activities that involved gaming but were not gambling-related. Ultimately, the term ‘Internet game’ was employed, rather than ‘video game’ or ‘digital game’, but the DSM-5 Working Group recognised that no single term was ideal and that additional qualifiers were needed.

The identification of critical points of difference in digital forms of gambling and gaming has a history of academic discussion over the last decade (Bramley & Gainsbury, 2014; Griffiths, King & Delfabbro, 2012; King, Delfabbro, Derevensky & Griffiths, 2012; King, et al., 2010; Wood, Griffiths, Chappell & Davies, 2004). Both activities may provide large rewards (‘jackpots’) delivered on a random or fixed-interval basis, employ similar on-screen audio-visual cues, provide social spaces for interaction and competition, and offer opportunities for advancement and progression. However, despite these commonalities in features of design, gambling and gaming products are not technically or legally equivalent, raising concern that many activities could be misclassified (Gainsbury, Hing et al., 2014; Owens, 2010; Parke, Wardle, Rigbye & Parke, 2013). This presents a number of practical problems both in terms of the public understanding of these activities (Humphries & Latour, 2013) and the ways in which societies respond to technology-based addictions. Epidemiological studies that use loose terminology, for example, may mislabel or conflate gambling and gaming and therefore fail to accurately detect problematic behaviour, potentially leading to inaccurate estimations of prevalence rates of problems in the community. Flawed data may then lead to improper allocation of health and treatment resources to certain subtypes of problems, and/or provide misguided or inappropriate measures that fail to reach the relevant populations at risk (e.g., gambling help services for gaming problems).

Common Intersecting Features of Gambling and Gaming

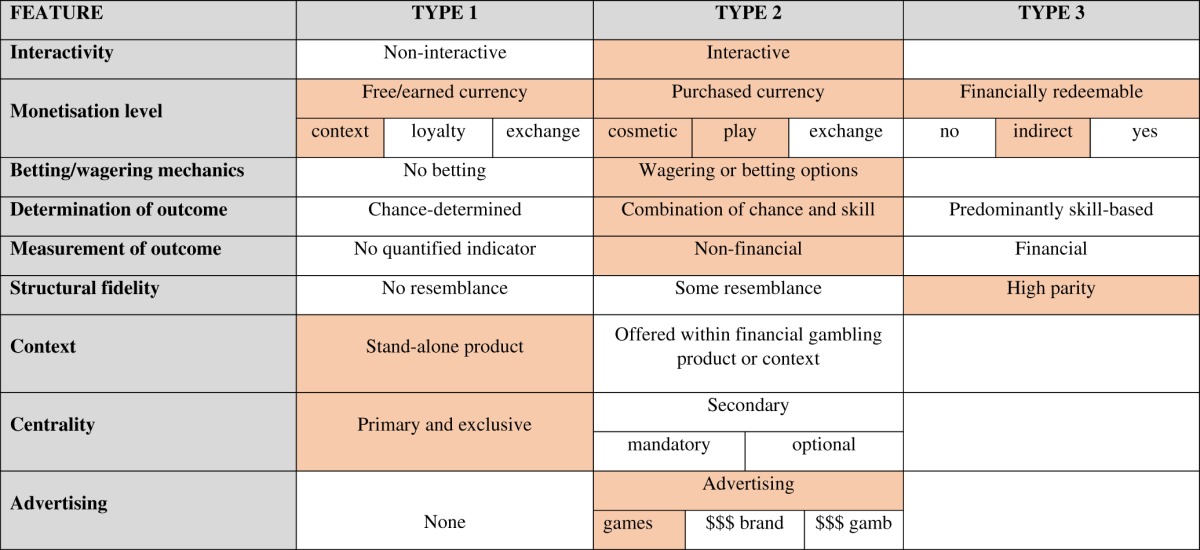

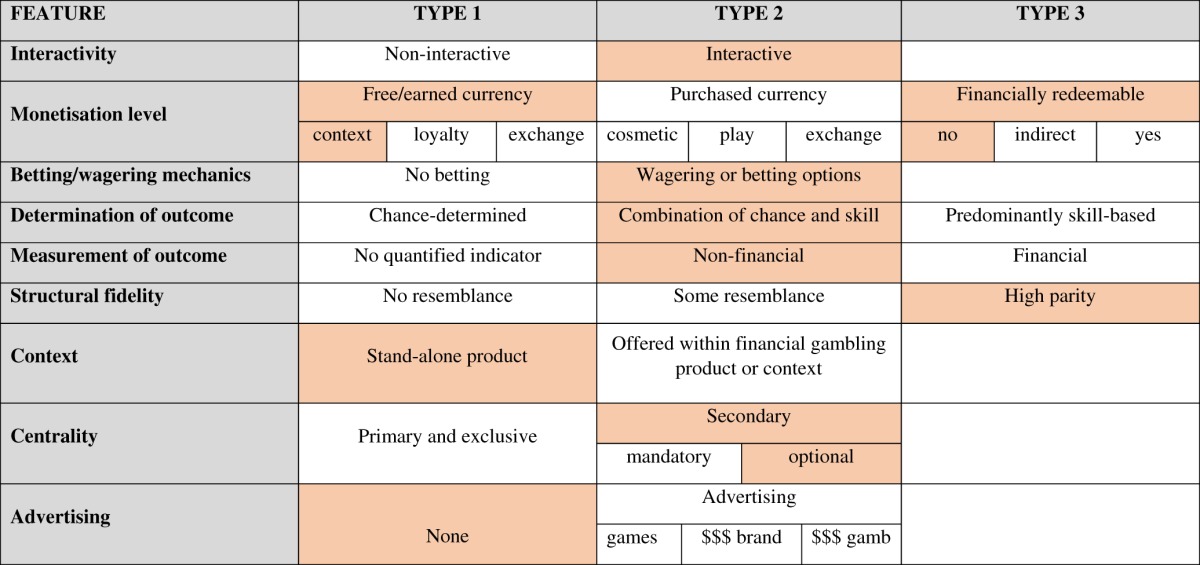

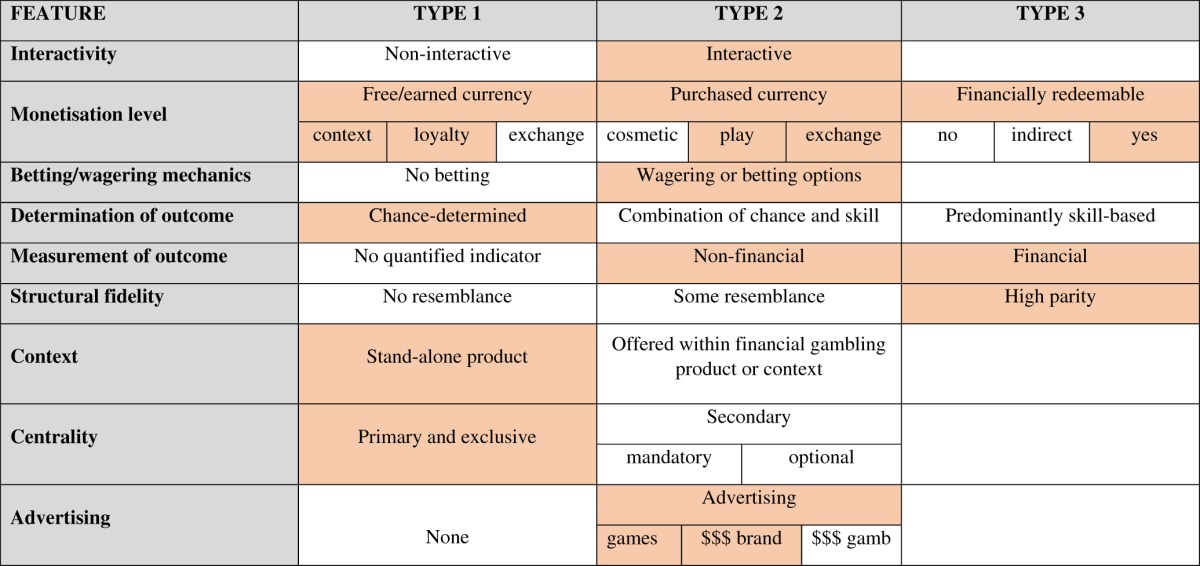

This paper proposes a set of key features likely to be present in gambling and gaming activities. After reviewing the literature on gaming and gambling convergence, including legal and academic taxonomies, the authors of this paper independently suggested features that they felt best captured the common structural properties of gaming and gambling. This process of deliberation led to two central propositions: (1) that gaming is principally defined by its interactivity, predominantly skill-based play, and contextual indicators of progression and success, and (2) that gambling is defined by betting and wagering mechanics, predominantly chance-determined outcomes, and monetisation features that involve risk and payout to the player. The element of financial payout was viewed as particularly important to the concept of gambling. We then considered these characteristics separately and in isolation of their contextual components (e.g., ‘betting mechanics’ and ‘financial expenditure’ were considered separately), and attempted to identify the broad range of permutations of structural designs using this framework. This process may not have been comprehensive in capturing all possible features and activities, but represents a preliminary attempt to summarise known features and activities. Table 1 presents all identified characteristics as a checklist, which may be used as a practical measure to evaluate digital activities. Three examples of completed checklists are provided, to demonstrate how certain activities may differ in their structural profile despite being generally referred to as ‘games’. Additional examples are available upon request.

Table 1.

A checklist for conceptualising gambling and gambling-like features in gaming activities

| FEATURE | TYPE 1 | TYPE 2 | TYPE 3 | ||||||

| Interactivity | Non-interactive | Interactive | |||||||

| Monetisation level | Free/earned currency | Purchased currency | Financially redeemable | ||||||

| context | loyalty | exchange | cosmetic | play | exchange | no | indirect | yes | |

| Betting/wagering mechanics | No betting | Wagering or betting options | |||||||

| Determination of outcome | Chance-determined | Combination of chance and skill | Predominantly skill-based | ||||||

| Measurement of outcome | No quantified indicator | Non-financial (currency, points, XP, unlocks) | Financial | ||||||

| Structural fidelity | No resemblance | Some resemblance | High parity | ||||||

| Context | Stand-alone product | Offered within financial gambling product or context | |||||||

| Centrality | Primary and exclusive | Secondary | |||||||

| mandatory | optional | ||||||||

| Advertising | None | Advertising | |||||||

| games | $$$ brand | $$$ gamb | |||||||

Interactivity

This refers to the notion that the action and stimuli in the activity changes based on the input or behaviour of the player. An activity that involves active player involvement and interaction may be considered interactive, whereas non-interactive activities involve passive viewing of an activity or viewing others, wherein the participant does not directly influence the outcome. All video games predominantly feature interactive elements, whereas this is not essential to gambling.

Monetisation

This category refers to the financial elements of play, including: (1) free/earned currency of game contextual value only (e.g., progression, completion), (2) free/earned currency that yields loyalty points exchangeable for credit, gifts or items of monetary value, (3) optional purchasable “vanity”/cosmetic items that do not impact the game mechanics, (4) optional purchasable currency for playing purposes (e.g., progression, completion), (5) optional purchasable currency that can be exchanged for gifts or other items, and (6) mandatory payment, entry fee or subscription to play. A useful qualifier in considering these types is whether the currency is redeemable for money or an equivalent (e.g., Bitcoin), including goods or services from the activity provider. The legal definition of gambling in many contexts typically refers to monetary payout to the player.

Betting/wagering mechanics

This category refers to the player’s option to stake something in their possession on the outcome of an event. It was recognised that, in some activities, players are able to engage in betting using virtual currencies and items that do not have any recognised financial value. It was therefore important to distinguish the mechanics of betting from its outcome in order to appropriately identify forms of simulated gambling.

Role of skill versus luck in determining outcomes

This refers to the way in which outcomes are determined in the activity, including (1) entirely determined by skill (e.g., competition); (2) entirely determined by chance or algorithms (i.e., draw, lottery), and (3) a combination of randomly generated or predetermined outcomes and skill-based outcomes.

The nature of outcomes

This refers to the outcome of player input and interactions, including betting and wagering mechanics. This may include (1) no indicator of outcome or progression, (2) non-financial indicators (e.g., virtual currency, points, unlocks, ranks, declaration of a winner), and (3) financial outcome (i.e., a payout). It was recognised that a typical requirement of gambling was financial outcomes.

Structural fidelity

This category refers to the degree of realism and structural resemblance of an activity to an established gambling (e.g., blackjack) activity. This includes: (1) minimal or no resemblance of a recognised activity, (2) some resemblance to a known activity, and (3) high level of parity to known activity.

Context

This category refers to the structural and situational positioning of an activity, either as (1) an activity is a stand-alone activity (e.g., a console game), (2) an activity is positioned within a larger activity (e.g., a mini-game within a console game), or (3) an activity linked to an external activity or service (e.g., a free-play game in an online casino).

Centrality

This refers to the proportion of gaming or gambling experiences within the typical experience of the activity, including with respect to gambling whether (1) gambling activity is the primary and exclusive activity, (2) gambling activity is secondary and mandatory, or (3) gambling activity is secondary and optional.

Advertising

This category refers to the presence of linked advertising material, particularly in relation to gambling activities. Some activities may not include features of gambling (e.g., betting) but nevertheless function as promotional material for financial gambling activities. Types include: (1) no advertising material, (2) presence of advertising for simulated gambling activities, (3) presence of brand-only advertising for gambling operators (online or land-based), and (4) presence of advertising for specific gambling activities and products (online or land-based). This category was included on the basis that some digital activities may feature links to recognised gambling, thereby enabling exposure to gambling and fluidity of transition between gaming and gambling.

Practical Use of the Checklist

Three examples of the completed practical checklist are presented to highlight the similarities and differences in digital activities that feature aspects of gambling. Table 2 presents a completed checklist for the social casino game Zynga Poker. This activity is a social media platform-based simulator of a poker variant. The game is interactive, incorporates purchasable virtual currency in addition to its free virtual currency, and involves an element of skill comparable to casino card games (i.e., there are optimal choices under certain conditions). Players may be prompted to spend money on virtual currency. There is no direct option for players to cash out their winnings; however, it is possible for players wanting to sell their currency to other players to join private game lobbies and deliberately lose hands in order to ‘gift’ currency (i.e., “chip dumping”). This process is slow and unregulated and offers no player protections. The game developer has reported that chip-dumping will result in player bans. The game has a high structural fidelity to casino card games, and also includes a series of mini-games (additional activities) that can be engaged in concurrently. In summary, the game involves betting and chance but lacks a complete monetisation cycle (i.e., player expenditure and associated return of financial currency) that defines legal gambling.

Table 2.

Conceptualising gambling-related content in the game, Zynga Poker

|

Table 3 presents a completed checklist for the stand-alone console video game, Red Dead Redemption, which is a Western-themed violent action story-based game that offers a side activity involving gambling with other players. All currency is virtual in nature and there is no ability to purchase additional currency. The game involves a realistic simulation of play, decision-making, and outcomes of standard poker card games. This content is considered a ‘side activity’ (i.e., not required for game progress) and has no connection to the wider playing community, such as via social media. The primary incentive to play is to earn virtual currency that can be spent in other areas of the game, as well as the competitive element of rising up the leaderboards.

Table 3.

Conceptualising gambling-related content in the game, Red Dead Redemption

|

Table 4 presents a completed checklist for the social game myVegas Slots, which is a casino-style game hosted on a social media platform. The activity’s promotional by-line is ‘Play casino games. Win real rewards’. The activity is interactive, incorporates purchasable virtual currency in addition to its free virtual currency, and involves chance-determined outcomes like an electronic gaming machine. Players are prompted to spend money on currency. There is no direct option for players to cash out their winnings, however, it is possible for players to earn loyalty points through playing that can then be redeemed for hotel rooms or other gifts or items, including special discounts and free play real money casino promotions (e.g., a coupon that is brought to the casino cashier and exchanged for $10 in chips that can be used to gamble for real money rewards). The game contains advertising for real world casinos. In summary, the game involves betting and chance and includes a loyalty point system to earn financial rewards. The game is integrated with social media and therefore players receive notifications and advertising for casino products.

Table 4.

Conceptualising gambling-related content in the game, MyVegas Slots

|

Summary and Challenges

This review highlights a number of common features in gambling and gambling activities, demonstrating that there are many possible permutations of digital activities. As shown, it is possible for activities identified and marketed as ‘games’ to feature many of the essential elements of gambling. Some digital games feature betting mechanics with purchasable virtual currency but with no option for financial payout, within a realistic simulated gambling environment. Although the play experience in these activities may be considered prima facie to be psychologically similar in many respects to a form of legalised gambling, an activity may nevertheless fail to meet one of the essential legal criteria of gambling (financial payout). One task for regulators may be to determine when certain game rewards are considered equivalent to money due to online trading systems (e.g., Zynga Poker) or special redemption offers (e.g., MyVegas Slots) that grant value to virtual items outside of the context in which they are situated. Another implication of this review is that players who are problematically involved in so-called ‘simulated’ gambling activities may be difficult to classify using diagnostic categories such as ‘gambling disorder’ given that financial harm may not be present or clinically meaningful. Classifying ‘non-gambling’ digital activities simply as ‘games’ may be a broad oversimplification that could compromise research agendas on Internet gaming disorder, given the heterogeneity of gaming populations. Looking forward, addiction researchers may need to consider certain hybrid or converging activities not only as types but also according to specific features of interest (e.g., financial expenditure), on the basis that some terms alone (e.g., “gambling game”) may not capture their complexity and associated risk.

Authors’ contribution

DK was responsible for preparing the manuscript, with feedback from all authors. All authors developed and provided feedback on the typology in this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: This work received financial support from the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation via a tender for a gambling and gaming review.

REFERENCES

- Bramley S., Gainsbury S. M. (2014). The role of auditory features within slot-themed social casino games and online slot machine games. Journal of Gambling Studies, DOI: 10.1007/s10899-014-9506-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainsbury S., Russell A., Hing N. (2014). An investigation of social casino gaming among land-based and Internet gamblers: A comparison of socio-demographic characteristics, gambling and co-morbidities. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Gainsbury S. M., Hing N., Delfabbro P. H., King D. L. (2014). A taxonomy of gambling and casino games via social media and online technologies. International Gambling Studies, 14, 196–213. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. (2013). Social gambling via Facebook: Further observations and concerns. Gaming Law Review and Economics, 17, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D., King D. L., Delfabbro P. H. (2012). Simulated gambling in video gaming: What are the implications for adolescents? Education and Health, 30, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the Classification of Computer Games 2012 within the Classification (Publications, Films and Computer Games) Act 1995.

- Humphries A., Latour K. A. (2013). Framing the game: Assessing the impact of cultural representations on perceptions of legitimacy. Journal of Consumer Research, 40, 773–795. [Google Scholar]

- King D. L., Delfabbro P. H. (2016). Early exposure to digital simulated gambling: A review and conceptual model. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 198–206. [Google Scholar]

- King D. L., Delfabbro P. H., Derevensky J. L., Griffiths M. D. (2012). A review of Australian classification practices for commercial video games featuring simulated gambling. International Gambling Studies, 12, 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- King D. L., Delfabbro P. H., Griffiths M. D. (2010). The convergence of gambling and digital media: Implications for gambling in young people. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26, 175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D. L., Delfabbro P. H., Kaptsis D., Zwaans T. (2014). Adolescent simulated gambling via digital and social media: An emerging problem. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Stanley. (2012). Social gambling: Click here to play. Morgan Stanley Research: Global. Retrieved from the Morgan Stanley website: http://linkback.morganstanley.com/web/sendlink/webapp/f/u4a8mcp4-3ohe-g001-b7cd-002655210101?store=0&d=UwBSZXNlYXJjaAA0NzE3NTY%3D&user=2t7a7p40q5buy-2365&_gda_=1479106416_6a55cefa848830ece67e9f0e40d5607a

- National Classification Code as amended under section 6 of the Classification (Publications, Films and Computer Games) Act 1995

- Owens M. D. (2010). If you can’t tweet’em, join’em: The new media, hybrid games, and gambling law. Gaming Law Review and Economics, 14, 669–672. [Google Scholar]

- Parke J., Wardle H., Rigbye J., Parke A. (2013). Exploring social gambling: Scoping, classification and evidence review. Final report submitted to the UK Gambling Commission. Retrieved from the Gambling Commission website: http://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/Gambling-data-analysis/Social-media/Exploring-social-gambling.aspx

- Wood R. T, Griffiths M. D., Chappell D., Davies M. N. (2004). The structural characteristics of video games: A psycho-structural analysis. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 7, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]