Abstract

We performed a literature review of existing benchmarking projects of health facilities to explore (1) the rationales for those projects, (2) the motivation for health facilities to participate, (3) the indicators used and (4) the success and threat factors linked to those projects. We studied both peer-reviewed and grey literature. We examined 23 benchmarking projects of different medical specialities. The majority of projects used a mix of structure, process and outcome indicators. For some projects, participants had a direct or indirect financial incentive to participate (such as reimbursement by Medicaid/Medicare or litigation costs related to quality of care). A positive impact was reported for most projects, mainly in terms of improvement of practice and adoption of guidelines and, to a lesser extent, improvement in communication. Only 1 project reported positive impact in terms of clinical outcomes. Success factors and threats are linked to both the benchmarking process (such as organisation of meetings, link with existing projects) and indicators used (such as adjustment for diagnostic-related groups). The results of this review will help coordinators of a benchmarking project to set it up successfully.

Keywords: Health-care benchmarking, quality improvement, hospitals, health facilities, quality indicators

Introduction

In an operating environment where funding for health care and research is both more insecure and competitive, health-care quality has become increasingly important.1 One possible way of helping health facilities to maintain and improve high-quality health care is by benchmarking their services.

Benchmarking in health care is defined as a process of comparative evaluation and identification of the underlying causes leading to high levels of performance.2 One important point in the definition of benchmarking is that it is not intended to be only a general measurement of one organisation (or part of an organisation) against another, but it also includes the study and transfer of exemplary practice.3 According to Stanford,4 a benchmarking process is described as the process of identifying leaders in the field so that the practice of these leaders may be understood and emulated. The benchmark is considered as the point of comparison. Another important point in benchmarking is to understand the processes by which performance can be enhanced, rather than simply to copy another process, as what is best for one organisation may be disastrous for another.5

Benchmarking was first developed for use by industries in the 1930s. In the health-care sector, comparison of outcome indicators dates back to the 17th century with the comparison of mortality in hospitals. Its utilisation as a structured method began only in the mid-1990s. It emerged in the United States and United Kingdom with the imperative of comparing hospitals outcomes to rationalise their funding.6 Van Lent et al. report the following definition of health-care benchmarking provided by Gift and Mosel:

Benchmarking is the continual and collaborative discipline of measuring and comparing the results of key work processes with those of the best performers. It is learning how to adapt these best practices to achieve breakthrough process improvements and build healthier communities.7

The rationale for health-care benchmarking is that institutions with excellent performance for a given outcome apply specific clinical practices that are most effective. They may also display structural or cultural organisational features that contribute to excellent outcomes.8 By visiting these centres and reviewing the evidence in the literature, teams from other institutions can identify these practices and organisational features. Then, by applying methods learned in quality improvement training, the teams should be able to implement the identified practices and to modify their organisations in ways that lead to better outcomes.8

Benchmarking in health care has also undergone several modifications: initially, benchmarking was essentially the comparison of performance outcomes to identify disparities. Then it expanded to include the analysis of processes and success factors for producing higher levels of performance. The most recent modifications to the concept of benchmarking relates to the need to meet patients’ expectations.6 Benchmarking can be extremely useful in supporting the development of good clinical practice because of its structure of assessment and reflection.9 In essence, benchmarking is a collaborative rather than a competitive enterprise that initially involves the sharing of relevant information on the delivery of care with other organisations. The findings are shared, and elements of best practice are adopted with the aim of improving performance. That said, good practice in one health-care provider cannot often be transferred to another health-care provider in the same country or across borders. Different factors will affect performance and need to be identified and addressed as part of action to achieve improvements.

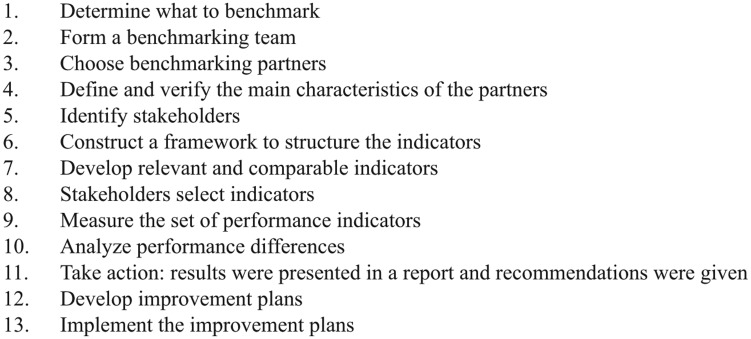

According to the Joint Commission Resources, there are two types of benchmarking: external and internal. Internal benchmarking compares different services in the same organisation. External benchmarking compares performance targets between different organisations. There are common activities to Benchmarking projects: determining what to study, forming a benchmarking team, identifying benchmarking partners, collecting data, analysing data and taking action.10 Van Lent et al. gave a detailed description of how a benchmarking process is conducted in health services. This 13-step process is detailed in Figure 1.7

Figure 1.

Description of the 13 steps of a benchmarking project according to Van Lent et al.7

In order to develop effective benchmarking of cancer hospitals, there is a need to fully understand the functioning of a benchmarking process and learn lessons from previously successful benchmarking projects. A critical review of existing or past benchmarking project can give a valuable insight. Examining the motivations for the development of a benchmarking project and for health facilities to participate can inform benchmarking coordinators on how to design a benchmarking project that is relevant and that the participants will subscribe to. Analysing the factors that contribute to the success of a benchmarking project and its threats can help coordinators in avoiding those pitfalls for their own benchmarking projects and in increasing their chances of successfully developing such projects. Listing the indicators used in benchmarking projects, and feedback on their use can avoid duplication of work and prevent the use of indicators that are not pertinent or not feasible in practice.

So far we have encountered no detailed review of existing benchmarking projects. One study11 reviewed literature on previous benchmarking of health care. However, this study, dating from 1997, reviews only 10 articles and is focused on health-care practices, not on the global benchmarking of health facilities. Thus, we have conducted this review of existing and past benchmarking projects of health facilities with the aim of learning lessons to apply in the design of a new benchmarking project. Specifically, we wanted to explore: the rationale for the development of those benchmarking projects, the motivation for health facilities to participate, the indicators used in those projects, their validity and how they influence the benchmarking process and the success factors and threats to those projects.

Methodology

We reviewed peer-reviewed and grey literature describing a benchmarking project for health facilities. We chose to also include grey literature related to the same projects, such as technical reports, user manual, or presentation of projects to stakeholders in order to gain more in-depth information on the process of the projects.

Search strategy

As our review is focused on health benchmarking, we operated our search from the PubMed database only and did not expand it to databases containing non-health journals. We initially searched for articles using the following keywords: [benchmark*] AND ([health facilit*] OR [Hospital*]). We undertook a subsequent search using the following keywords [Benchmark*] AND [Europe*] OR [international] in order to include European and International Benchmarking projects. Through snowballing, we included relevant articles found in the references. After enlisting the projects mentioned in the articles, we searched for grey literature related to those projects using the website of the benchmarking organisations listed or through a general Internet search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We defined the scope of our analysis to include all benchmarking projects conducted in health facilities. A health facility is a place that provides health care. It can include a hospital, a clinic, an outpatient care centre or a specialised care centre (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/healthfacilities.html). In our analysis, we chose to include literature related to projects that were defined by the author or the organisation managing it as a benchmarking project and that focused on either the entire health facility, or on one or more specialised unit or service within this health facility. In order to be included, a publication had to explain the development of a benchmarking project (including indicators selection) and/or give critical feedback on the benchmarking project, such as assess its impact, identify success factors or threats, or draw lessons. We encountered one article referring to a project that aimed to measure health-care systems, included but not limited to hospital care.12 We chose to include this article because it was relevant to the review.

Data collection

For each benchmarking project, we collected general information about the project, analytical data and indicators used in those projects. The general information was extracted in order to be able to draw a general picture of the benchmarking projects and be able to describe them. It included the following:

The domain of application of the project (such as palliative care, oncology, emergency care …), and its setting (general hospital, cancer centre …);

The geographical area;

The scope of the project (is it a regional, national, international project?);

The number of facilities benchmarked;

The dates of the project.

The analytical data were chosen according to our review objective. They included the following:

The rationale for the development of this project (why was it developed?);

Data on the participation of facilities in this project (what were the incentives to participate, did the participation rate increase or decline over time?);

If and how identification of leaders and sharing of best practices was organised;

The practice of the benchmarking project regarding data sharing and anonymity;

The impact of the benchmarking project;

The success factors and threats to the completion of the project.

Finally, we listed indicators used in each project whether the projects used existing indicators or developed new ones as part of the benchmarking project and if so, how.

The data extraction for each study was carried out by one author (F.T.) after the data extraction methodology was tested among a sample of six studies by two authors (F.T., M.S.). The data extraction forms can be found in Appendix 1 in supplementary material.

Results

Literature found

We found 38 peer-reviewed articles and 11 documents from the grey literature. From these 38 research articles, 33 reported the outcome of one or several benchmarking projects and 5 related the development of a benchmarking project or indicators to use for benchmarking projects. Of the 11 documents from the grey literature, 4 presented the results of benchmarking projects for stakeholders and 6 were practical manuals for users. One project (Believe) was referred to in a peer-reviewed article that did not report on its implementation or development. Therefore, we included only the grey literature and not the peer-reviewed article related to that project.

Description of the benchmarking projects

We found a total of 23 benchmarking projects reported, including 4 that were only in the development phase at the time the articles were published (see Table 1). Most of the projects (N = 12) had a national scope, followed by international (N = 5), regional (N = 4) or European (N = 2) projects. The benchmarking projects applied either to the whole hospital, or to a care specialty (usually oncology) or a service (such as palliative care or emergency care). The complete overview of benchmarking projects is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the benchmarking projects retrieved.

| Benchmarking project number | References (peer-reviewed articles) | References (grey literature) | Name of the project | Domain of application | Geographical area(s) | Scope | Nr of health-care facilities benchmarked | Dates/period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP1 | 13–15 | National Oncology Practice Benchmark | Oncology | USA | National | 187 | 2007–2014 | |

| BMP2 | 16 | Benchmarking Lombardy | General hospitals | Lombardy (Italy) | Regional | 150 | 2011 | |

| BMP3 | 17 | Benchmarking for length of stay | General hospitals (length of stay) | Netherlands | National | 69 | 2006 | |

| BMP4 | 18–20 | Benchmarking of breast cancer units | Breast cancer | Germany | National | 220 (in 2007) | 2003–present | |

| BMP5 | 21, 22 | Benchmarking trauma centre | Trauma centres | UK and Australia | International | 2 | 2001–2002 | |

| BMP6 | 23–27 | 28 | National Mental Health Benchmarking Project | Mental health in 4 domains | Australia | National | 23 | 2005–2008 |

| General adult | ||||||||

| Child and adolescent | ||||||||

| Older person | ||||||||

| Forensic | ||||||||

| BMP7 | 9 | 29 | National Care of the Dying Audit of Hospitals (NCDAH) | Palliative care | UK | National | 40 | 2006–2007 |

| BMP8 | 30, 31 | 32–34 | Performance Assessment Tool for Quality Improvement in Hospitals (PATH) | General hospitals | Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Slovakia, South Africa | International | 51 | 2005–2006 |

| BMP9 | 35 | Danish Indicator Project | General Health care | Denmark | National | 5 | 2003–2008 | |

| BMP10 | 36 | Nordic Indicator Project | Generic and disease-specific indicators, plus other general health service | Denmark, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden | European | Not specified | 2005 | |

| BMP11 | 37 | 38 | Cancer Network Management Benchmarking | Cancer care | UK | National | 7 | 2007 |

| BMP12 | 39 | Emerge | Emergency care | Switzerland | National | 12 | 2000 | |

| BMP13 | 40 | Benchmarking by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) | Clinical productivity in cancer care | USA | National | 13 | 2003 | |

| BMP14 | 41–43 | 44 | Benchmarking Collaborative Alliance for Nursing Outcomes (CALNOC) | General hospitals | California, Washington, Oregon, Arizona, Nevada, Hawaii | Regional | 196 | Since 1996 |

| BMP15 | 7 | Benchmarking of comprehensive cancer centres | Cancer care (comprehensive cancer centre) | Not specified | International | 3 | 2009 | |

| BMP16 | 7 | Benchmarking of radiotherapy departments | Cancer care (radiotherapy departments) | Not specified | International | 4 | 2009 | |

| BMP17 | 7, 45 | Benchmarking of chemotherapy day units | Cancer care (chemotherapy day units) | USA and Europe | International | 3 | 2005 | |

| BMP18 | 46–50 | 51–53 | Essence of Care | Nursing care | UK | National | Not specified | 2001–2010 |

| BMP19 | 54 | BELIEVE | General hospitals (pain control) | Aquitaine (France) | Regional | 32 | 2009–2012 | |

| BMID1 | 55 | Consumer Quality Index | Cancer care | Netherlands | National | – | – | |

| BMID2 | 56 | Hospital Information System (HIS) | Hospital Information System | Austria | National | – | – | |

| BMID3 | 12 | OECD Health-Care Quality Indicators | General health service | EU countries | European | – | – | |

| BMID4 | 57 | Benchmarking patient satisfaction | Patient satisfaction in general hospital | Lombardy (Italy) | Regional | – | – |

BMP: Benchmarking Project number; BMID: Benchmarking Indicators Development; OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; EU: European Union.

Indicators used in benchmarking projects

According to Donabedian,58 indicators can be classified into three categories: structure indicators (measuring all factors that affect the context in which the health care is delivered), process indicators (the sum of actions that make health care) and outcome indicators (effects of health care on patients or population). Most of the projects use a mix of process, structure and outcome indicators (N = 6) or a mix of process and outcomes (N = 9). Four projects use process indicators only, two used a mix of process and structure indicators and two used outcome indicators only. Two projects used unusual indicators: one about Hospital Information System and one about clinical productivity. One benchmarking project (National Oncology Practice) used two levels of indicators with ‘core’ data and ‘additional’ data. Many indicators focus on patients/user satisfaction. The complete list of indicators used in those projects, including the methodology used to select or develop those indicators can be found in Appendix 2 in supplementary material.

For most projects (N = 15), benchmarks were developed as part of the project and for others (N = 4) the project coordinators used established benchmarks such as national or international standards. The organisations used classical methods to develop and select indicators, such as expert consultation (including Delphi surveys or other consensus methods), literature search, and interviews or clinical guidelines in place. Only 1 project (the Essence of Care project) included patients and carers in the definition of best practices for benchmarks.

Analysis of the benchmarking projects

A summary analysis of the benchmarking projects can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the analysis of benchmarking projects.

| Benchmarking project number | Project | Rationale for the benchmarking project | Participation of centres in the programme | What impact did the benchmarking project have? | Success factors | Failure factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP1 | National Practice Benchmarking | To promote measurement of clinical activity. | Decrease of participation after 8 years. | – | To make the survey more accessible, it was stratified into 2 sections (minimum data set and extra). | – |

| BMP2 | Benchmarking Lombardy | To give feedback to hospitals about their performance and create a culture of evaluation. Few existing analysis of performance. | – | It helped directors draw plans to improve critical areas. | Adjustment for diagnostic-related groups. | Public disclosure of results might promote risk-averse behaviour by providers (discourage them from accepting high-risk patients). This is subject to debate. |

| Use of regional administrative data so employees more likely to accept the results. | ||||||

| BMP3 | Benchmarking for length of stay | To determine the potential for reduction in length of stay. | At the beginning: full participation rate, then more hospitals stopped participation because engaged in other compulsory registration projects. | It has helped to identify the medical specialties for which the decrease of length of stay is the most possible. | – | – |

| BMP4 | Benchmarking of breast cancer units | To ensure that care provided to breast cancer patients was based on clinical guidelines and quality assurance. | Participation is voluntary. Increase in specialist breast centres participating in the programme from 2003 to 2009. | Improvement on many clinical indicators and indicators of use of clinical guidelines. | The project was voluntary and used anonymised data. | – |

| BMP5 | Benchmarking of trauma centres | To improve outcomes of the trauma centres. | – | Highlighted the need for greater cooperation between trauma registry programme coordinators to ensure standardisation of data collection. | – | Crude hospital mortality is not a robust indicator for trauma centres as it does not take into account mortality after discharge. |

| BMP6 | National Mental Health Benchmarking Project | Part of the National Mental Health Strategy. | Selection criteria set for the candidate organisations. | Modification of practices. | Commitment of the management and securing resources. | Data quality and variability in information systems/data interpretation. |

| Feeding back benchmarking data to clinical staff to maintain their motivation to the project. | ||||||

| Forums for participants provided them the opportunity to discuss the performance of their organisation and draw lessons from other organisations. | ||||||

| BMP7 | NCDAH | Measuring quality in palliative care is challenging. | There was a 13% increase in programme participation between round 2 and round 3. | Improvement in practices and in communications between health professionals. | Holding a workshop for participants to reflect on data, enhance understanding and learn from others. | The feedback report should not have too heavy data or contain too complex information. |

| Participants found exercise was useful and improved care in the organisation. | ||||||

| BMP8 | PATH | In Europe, hospital performance assessment is a priority for WHO Regional Office for Europe. There are few initiatives to compare hospital performance internationally. | 66 hospitals initially registered for participation but a total of 51 hospitals actually participated. | Participation in the project facilitated the integration of different quality assessment activities and data collection. | If the project focuses much more strongly on international comparisons and improved validity. | Lack of personnel, expertise and time for participating hospitals to collect data. |

| In some countries it was a stepping stone for starting quality implementation projects (when there was none). | Some issues addressed by the indicators felt too vague and difficult to put in place. | |||||

| Competing priorities and reorganisation of hospitals. | ||||||

| Competing or overlapping projects. | ||||||

| BMP9 | Danish Indicator Project | There is no systematic outcome assessment of patient care. | Participation was mandatory for all hospitals and relevant clinical departments and units treating patients with the 8 diseases. | Increase in the percentage of patients receiving recommended care and interventions according to national practice guidelines. | Easy data collection: in the participating hospitals, data are collected electronically and transmitted safely via the Internet to the project national database. | – |

| Improvement in waiting time. | In Denmark it is possible to assign a unique patient identifier, thus facilitating data collection. | |||||

| For lung cancer patients, a concerted action has been set up in order to improve this area. | ||||||

| BMP10 | Nordic Indicator Project | Need to document and monitor the quality of health service performance. | – | It has allowed us to gather evidence about differences in survival rate from prostate cancer. | – | Not all countries are equally able to track patients after hospital discharge (some countries assign unique patient identifiers, others not). |

| Desire for transparency and accountability. | ||||||

| BMP11 | Cancer Network Management Benchmarking | The United Kingdom has the worst cancer survival rate in Europe. Benchmarking project set up to support a quality improvement strategy. | – | – | Using a mix of structure, process and outcome indicators. | – |

| BMP12 | Emerge | To improve the quality of care in hospitals. | Participation was voluntary. | Quality improvement between the two cycles of benchmarking. | Interpretation of results should be guided by a culture of organisational learning rather than individual blame. | In emergency department, there is a selection bias in patients’ survey. |

| BMP13 | Benchmarking NCCN | There is no information on clinical productivity. | Participating centres are members of the NCCN. | – | – | – |

| BMP14 | Benchmarking CALNOC | Nurses comprise the largest group of professionals employed in hospitals, and are thus uniquely positioned to significantly influence patient safety and quality of care. | Low attrition rate (fewer than 3% hospitals withdrawing from project since 1998). | Participating CALNOC hospitals reduced their Hospital Acquired Pressure Ulcer rates from 10% to 2.8% with half of the hospitals achieving 0%. | Outcome measures include not only injuries but also near-misses, allowing us to correct the system. | – |

| Measures are tied to reimbursement possibly providing financial incentives for hospitals to participate. | CALNOC also offers educational and consultancy service in best practices, possibly contributing to success of the project. | |||||

| BMP15 | Benchmarking of Comprehensive Cancer Centres | – | Centres selected by a case study. | – | Internal stakeholders must be convinced that others might have developed solutions for problems that can be translated to their own settings. | Due to different reimbursement mechanisms in different countries the use of financial indicators is complex. |

| Management must reserve sufficient resources for the total benchmarks. | ||||||

| Limit the scope to a well-defined problem. | ||||||

| Define criteria to verify the comparability of benchmarking partners based on subjects and process. | ||||||

| Construct a format that enables a structured comparison. | ||||||

| Use both quantitative and qualitative data for measurement. | ||||||

| Involve stakeholders to gain consensus about the indicators. | ||||||

| Keep indicators simple so that enough time can be spent on the analysis of the underlying processes. | ||||||

| For indicators showing a large annual variation in outcomes, measurement over a number of years should be considered. | ||||||

| Adapt the identified better working methods so that they comply with other practices in the organisation. | When the CCC is in a middle of a complex merger. | |||||

| BMP16 | Benchmarking of radiotherapy department | – | Centres selected by a case study. | – | Measuring the percentage of patients in clinical trials not useful for radiotherapy. | |

| As some indicators were subject to large yearly variations, measuring indicators over a 1-year period does not always give a good impression of performance. | ||||||

| BMP17 | Benchmarking of chemotherapy units | It is part of applying a business approach to improve the efficiency of chemotherapy by identifying best practices. | Centres selected by a case study. | Best practices from benchmarking were used in discussion about the planning system. | Benchmarking should not only be used for comparison of performance, but also to gain insight into underlying organisational principles. | Using business jargon can make medical and care professional left out. |

| Benchmarking made the partners aware that other organisations with similar problems were able to achieve better outcomes. | ||||||

| BMP18 | Essence of Care | There are unacceptable variations in the standards of care across the countries and reports showed a decline in the quality of care. | No information. | Many improvements were reported at the local level rather than institutional level. | High awareness of the project among nurses. | Although the definition of standards was detailed, the process for measuring them was not. |

| Issues of costs associated with litigation for negligence might be a factor for the development of quality initiatives. | Improved motivation of staff after receiving positive feedback. | The project is seen as a top priority at the clinical governance level. | Lack of dedicated funding. | |||

| In one area the experience of the benchmarking process itself has brought together sections of the division that would not normally meet. | Lack of interest by physicians (seen as a nurse initiative). | |||||

| The benchmarking process has given more power and authority to matrons. | ||||||

| BMP19 | BELIEVE | To improve pain control. | Mix of public and private health facilities. Medical and surgical services. | 52 action plans written including training, adaptation of patient record, protocols, development of pain measurement tools. | Project piloted by the CCECQA, an organisation that most hospitals are familiar with, and that has a good reputation for its work. | When questions are difficult to interpret. |

| Pain control put higher on the agenda and staff more aware of it. | Benchmarking process was transparent. | Too heavy workload. | ||||

| Improvement of practices. | Before audit visits, a meeting was organised to share experiences. |

BMP: Benchmarking Project number; CALNOC: Collaborative Alliance for Nursing Outcomes; CCC: Comprehensive Cancer Centre; CCECQA: Committee for Coordination of Evaluation and Quality in Aquitaine; WHO: World Health Organisation; PATH: Performance Assessment Tool for Quality Improvement in Hospitals; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

List of indicators used in projects in Appendix 2 in supplementary material and full table on the website http://www.oeci.eu/benchcan

Rationale for the development of benchmarking projects

Improving quality of care, fighting inequalities in care delivery and measuring quality were presented as the main reasons for developing a benchmarking project. Most of the projects were the results of a ‘top-down’ approach to quality of care improvement. Indeed, 12 projects were initiated by an official health body, such as a health agency or administration and 4 projects were reported as being the initiative of the network of facilities (for the remaining 3 projects, it was not specified). Three projects were developed to measure care specialties not usually measured, or not in-depth, such as clinical productivity, trauma care or palliative care. For 1 project (the benchmarking of chemotherapy units), the benchmarking was part of a business approach to improve their efficiency.45 One article discussing the ‘Essence of Care’ project mentioned the rise in litigation costs for negligence (in the case of pressure ulcers) as one of the reasons for developing quality control initiatives.46

Incentives of hospitals to participate in benchmarking

We found little information about the participation of hospitals or health facilities in the benchmarking process. For 11 projects, the participation was noted as voluntary and for only 1 project (the Danish Indicator Project), participation was mandatory.35 For 7 projects, it was not documented whether participation was mandatory or voluntary. An increase in the participation in benchmarking projects was noted for the benchmarking by the German Cancer Society/German Senology Society (Deutschen Krebsgesellschaft (DKG)/Deutschen Gesellschaft für Senologie (DGS)) and the National Care of the Dying Audit of Hospitals (NCDAH) project. A decrease in participation was noted for 2 projects: the National Practice Benchmark after the project has been running annually for 8 years,15 and the Benchmarking of length of stay in hospitals by the National Medical Registration. In the latter case, the decrease in participation was explained by the fact that more hospitals became engaged in another compulsory registration project.17

Little information was available about the incentives for centres to participate in benchmarking projects. For the Collaborative Alliance for Nursing Outcomes (CALNOC) project, a financial incentive was mentioned. Indeed, the measure of quality indicators is tied to reimbursement from Medicaid and Medicare. From 2009 onward, Medicaid and Medicare services withheld reimbursements for treatments related to hospital-acquired pressure ulcers, one of the indicators measured by the project: hence a need to improve quality in those areas.

Impact of the benchmarking projects

A positive impact was reported for 14 projects. Two benchmarking projects resulted in changes at the institutional level, such as the setting up of action plans in critical areas.16,54 Improvements in clinical outcome indicators are reported for the benchmarking of a breast cancer unit in Germany and the CALNOC project, while improvement in practices or use of guidelines are also reported for the Benchmarking of breast cancer units in Germany, NCDAH project, Danish Indicator Project, Essence of Care and BELIEVE projects. Three projects have resulted in increased communication or collaboration between health professionals or different services in a hospital that did not communicate well (Benchmarking of trauma centres, NCDAH, Essence of Care). Two benchmarking projects resulted solely in the validation (or invalidation) of a method or indicators. This is the case for the benchmarking project conducted by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, which developed and tested a methodology to measure clinical productivity of oncology physicians, without measuring changes in this productivity induced by the project; or a second Benchmarking of trauma centres project. Similarly, the Benchmarking for length of stay17 or the Nordic Indicator36 projects have enabled to gather data and draw policy conclusions but no impact of the project on those indicators is reported.

Success factors or threats linked to the benchmarking process

One article exploring the benchmarking of Comprehensive Cancer Centres7 produced a detailed list of success factors for benchmarking project (see Table 2).

One of the factors mentioned – management’s dedication to the benchmarking project – was also mentioned as a critical determinant for success or failure in three projects such as the Performance Assessment Tool for Quality Improvement in Hospitals (PATH) project,30 the Essence of Care project49 and the Australian National Mental Health Benchmarking Project.25 Whether results should be made public or not was debated. Literature about the Benchmarking project by the DKG/DGS mentioned the anonymity of centres as one success factor for participation of centres.20 But Berta et al.16 argued that public disclosure of results might promote risk-averse behaviour from providers, discouraging them from accepting high-risk patients, while acknowledging that it can drive quality improvement.

Organising a meeting for participants, either before or after the audit visits, was mentioned as a success factor in three projects.9,25,54 Those workshops or forums provided the opportunity for participants to network with other organisations, discuss the meaning of data and share ideas for quality improvements and best practices.

The existence of other competing or overlapping projects was mentioned as a threat for two projects. It is reported that this co-existence sometimes provided benefits, sometimes threatened the PATH project,30 but regarding the Benchmarking project for length of stay, the fact that some hospitals engaged in other compulsory registration project explained a drop of participation after few years.

Finally, only for seven projects did the literature mention the identification of leader health facilities and sharing of best practices. This was organised either through tools or databases developed to that effect, or through meetings, workshop or networking events between hospitals. For the remaining projects, no mention of sharing best practices is made.

Success factors and threats linked to indicators or data collection

One recurring issue from the benchmarking projects concerns the crucial importance of the complexity and amount of data. In the NCDAH project, while most participants agreed that the feedback report contained the right amount of information, some participants felt that the data were too complex and the reports contained too much information. Participants in the BELIEVE benchmarking project felt the burden of participating in the project was too heavy or not properly evaluated beforehand. An evaluation of the PATH project reported that there was a major agreement that the burden of data collection was too important for the following indicators: prophylactic antibiotic use, surgical theatre use, training expenditure and absenteeism.

In addition to a data collection burden, definition and methodology is of crucial importance. The feedback of the PATH project reported major disagreements regarding the definition of three indicators: training expenditure, health promotion budget and patient-centredness. Those indicators were later abandoned for the project.31,30 Participants in the BELIEVE project also reported difficulties in interpreting the questions (that were resolved during training sessions).

Adjusting indicators for diagnostic-related groups was mentioned as one success factor of the Benchmarking project in Lombardy.16 Indeed, this adjustment allowed for fairer comparison and enabled to identify the areas that need improvement the most.

Using a combination of process and outcome indicators, rather than outcome only measures was considered as beneficial. The advantage of process indicators over outcome indicators is that they reflect true variations in care delivery, while outcome indicators can be influenced by other factors.57 Including process indicators in the benchmarking projects allows us to identify the remedial actions. This finding is similar to one of the conclusions related to the CALNOC project: outcome measures include near-misses, which allows us to correct the system.43

Different projects had different policies regarding public release of data. Two projects (the National Practice Benchmark project and the NCDAH project) released only anonymised data or average results, or no data at all, even for the project participants. Two projects disclosed nominative data but only for the benchmarking participants while releasing only anonymised data to the public (CALNOC project and Australia’s mental health project). Six projects disclosed hospital data publicly but anonymously. The Lombardy Benchmarking project shared the results with health-care providers outside the benchmarking project and sharing data with patients was under discussion. And two projects (Nordic and Danish Indicator projects) publicly disclosed nominative hospital data. For the remaining projects, data release or sharing between participants was not mentioned.

Finally, other lessons mentioned in the articles are: the use of regional data might be more acceptable;16 crude mortality rate might not be a valid indicator as it does not take into account mortality after discharge,22 due to different reimbursement mechanisms (in different countries) the use of financial indicators is especially complex,7 and as some indicators were subject to large year-to-year variations, measuring indicators over a 1-year period does not always give a good impression of performance.7

Discussion

The aim of our review was to analyse different European or international benchmarking projects of hospitals or health-care facilities in order to draw important lessons, avoid duplication of work and identify the success factors and threats to benchmarking of hospitals. We analysed the peer-reviewed and grey literature related to 18 benchmarking projects and 4 indicator development projects for benchmarking.

Improving quality of care was mentioned as the most important motivation for health authorities to develop benchmarking projects, showing a rising demand for accountability and transparency of care.36 In some cases, it seems that this demand has financial consequences. Indeed, a rise in litigation costs linked to care negligence and withheld reimbursement for treatment of conditions preventable by improved care are mentioned as reasons for the development of or participation in, respectively, the Essence of Care and CALNOC projects. This issue has been more often documented in the United States. Indeed, the rise of the performance measurement and comparisons by the Health Care Financing Administration (the agency responsible for administering the Medicaid and Medicare programmes) has also been noted in a previous article discussing quality measuring in US nursing homes.59 Those aspects could be viewed as direct (in the case of the CALNOC project) or indirect (for the Essence of Care project) incentives. The effect of financial incentives for performance on hospitals is a controversial subject. A recent review of Pay for Performance initiatives summarised that individuals tend to respond more strongly to negative incentives than to positive incentives of equivalent size, but negative incentives are likely to be perceived as unfair and may result in negative reactions.60

As explained earlier, the decision to initiate a benchmarking project was most often a top-down one; but the participation of facilities was voluntary for all projects except one. For only two projects, a possible financial motive for facilities was mentioned (costs of litigation or withheld Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement due to poor outcomes). But we did not find other information about the incentives of hospitals to participate in such projects. The increase in participation of the Benchmarking of breast cancer units by the DKG/DGS and the NCDAH possibly reflect a growing adhesion and popularity of those projects. However, we did not find an analysis of the reasons for that increasing success. On the other hand, some projects have seen their participation decline over time. This could be due to difficulties in maintaining interest in participants, or due to the appearance of concurrent quality improvement projects. Indeed, the existence of competing or overlapping projects was mentioned as one threat for the implementation of the PATH project. We did not observe any apparent link between the number of facilities participating in the project and the outcome of the project or the success factors and threats.

In most documented cases, the impact of the project was reported as positive, resulting in either change at the institutional level, improvement in clinical outcomes, increased use of guidelines or improvements in communication. It is interesting to note that, while most projects used a mix of structure, process and outcome indicators or process and outcome indicators, most of the reported positive impact of the benchmarking projects are linked to process measures. Only one benchmarking project reports an impact in terms of outcomes. Some of the success factors for the conduct of a benchmarking project include the necessity to use comparable data (adjusted for case mix or other factors). Unsurprisingly, this information is consistent with the findings of a previous literature review, as is the recommendation to organise a meeting for participants.11 Indeed, it reports from previous studies that focus group meetings and interviews are a central component of benchmarking, providing information that serves to identify problems, issues, concerns and possible unmet needs from the perspective of the users of the service and service providers. This dynamic of comparing and learning from each other distinguishes benchmarking from other quality improvement processes.

The issue of making data public or not is one point of controversy between different articles. In one study,20 it was noted that the anonymity of centres was a success factor, while another article argued that the public disclosure of results was suspected of promoting risk-averse behaviour from providers but acknowledged that such disclosure could drive quality improvement. In our review, the practice of public disclosure of nominative data was rare but some projects only shared anonymised or average data, even within the benchmarking participants. This controversy is not limited to the articles included in our review. Advocates of report cards believe that publicly releasing performance data on hospitals will stimulate hospitals and clinicians to engage in quality improvement activities and increase the accountability and transparency of the health-care system. Critics argue that publicly released report cards may contain data that are misleading or inaccurate and may unfairly harm the reputations of hospitals and clinicians. They also are concerned that report card initiatives may divert resources away from other important needs.61 Although there is evidence that public reports do not affect patients’ choice of hospital,62 the impact on quality is unclear. It appears that hospitals who are subject to public reporting have engaged in quality improvement initiatives,61,63 but the evidence on process and outcome indicators is mixed.61,62

Projects have used a wide range of approaches to define and select indicators to be used in the projects, such as interviews, focus groups, literature reviews and consensus surveys. We have noted that one project (Essence of Care) included patients’ feedback when defining best practices measured by indicators. This project was the only one that used this approach. It appears that the involvement of patients in the quality policy of a health facility is highly encouraged.64 However, it seems that this practice is still not widely implemented.64 The implication of patients in the definition of quality indicators and research on this subject seems very scarce: a systematic review conducted in 2013 found only 11 scientific articles describing how patients are involved in quality indicators development.65 None of those studies compared different approaches or explained how their contribution led to changes in the resulting quality indicators. Our review confirms those results as the literature related to the ‘Essence of Care’ project did not detail precisely how the patients and carers were involved in the definition of best practices. More research is needed on this subject.

Other projects, while not involving patients in indicators selection, used patients’ satisfaction surveys as part of the indicators measuring the quality of their hospital. The literature on this subject confirms that patient experience measures are an appropriate complement to clinical quality measure. Patient satisfaction is linked with better patients’ adherence to treatment protocol, best practice clinical processes, better safety culture and better clinical outcome.66

Policy implications

Policy makers or programme coordinators who want to develop benchmarking projects of hospitals or health facilities should learn lessons from previous projects. First and foremost, ensuring the commitment to the project by the management team of hospitals participating and the allocation of sufficient resources for the completion of the project is paramount to the development of a benchmarking exercise. Given the time and efforts that are requested for participation in a benchmarking project, developers of benchmarking projects should reflect on incentives for health facilities to participate continuously over time.

One important challenge to the development of a benchmarking project is the issue linked to data sharing. On one hand, sharing data between partners of a benchmarking project is essential for hospitals to learn best practices; on the other hand, the request to share confidential data could deter health facilities to participate in such a project and therefore jeopardise its success. The benchmarking projects reviewed adopted diverse policies in the project reviewed, but perhaps anonymising or clustering data could be a suitable option. Project coordinators should develop clear guidelines on this subject in consensus with the partners and participating health facilities.

In terms of indicators, using a mix of process, structure and outcome indicators seems the most effective, and adjusting the clinical outcome indicators for diagnostic-related-groups is more appropriate and accepted, as it leads to fairer comparisons between hospitals. Lack of clarity around the calculation indicators has been reported as a problem and can lead to invalid results and unfair comparisons. It needs to be ensured that the methodology for indicators is very clear and as less a burden as possible and is feasible for all participants. Finally, coordinators of benchmarking programmes should provide opportunities for participants to meet and exchange with other participants in order to promote the dissemination of good practices.

Strength and limitations of the review

Our review has analysed different benchmarking projects in the world. To our knowledge, this is the first in-depth and global analysis of the benchmarking projects of health-care facilities performed. We were able to collect relevant information to be used for the development of future benchmarking projects. One of the strengths of our review is that we have included material from the grey literature, as well as peer-reviewed articles. However, our review is not without limitations. While we have tried to include a diversity of benchmarking projects, it should be noted that our review was not meant to be exhaustive or systematic. We might have missed national projects with material written in languages other than French or English. We started from a search of scientific literature and, by snowballing, included grey literature related to a benchmarking project. However, many projects were not reported in any peer-reviewed articles, so we did not include them. This is justified by our objective to retrieve in-depth analysis and feedback from project, which might be missing in grey literature publications.

We should note also limitations about the data we encountered. As the evidence on the impact of benchmarking project and on sharing data to yield best practices was limited, we were not able to perform a strong analytical comparison between studies. However, we were able to describe how benchmarking studies report on those projects.

Conclusion

We reviewed the peer-reviewed and grey literature about benchmarking projects in order to draw lessons that can be applied when developing new benchmarking projects, avoid duplication of work and identify the success factors and threats to the benchmarking of hospitals. We hope that this review and the related material that we present will be of interest to those who plan to participate in or coordinate a benchmarking project, or research on benchmarking in health care.

Although the literature we studied reported a positive impact for most of the benchmarking projects, this impact is mainly at the structure and process level. There is a lack of evidence about the impact of benchmarking on patients’ benefit. Future research on benchmarking should investigate the long-term impact of benchmarking health facilities, particularly in terms of patient’s outcomes and the learning of best practices.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Edit Sebestyén for her comments in the interim version of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency of the European Commission under the grant number 2012-1211. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the article.

Reference

- 1. Timmermans S. The Gold Standard: the challenge of evidence-based medicine and standardization in health care. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2003, 269 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ellis J. All inclusive benchmarking. J Nurs Manag 2006; 14(5): 377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jones CS. Towards benchmarking in British acute hospitals. Health Serv Manag Res 2001; 14(2): 125–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stanford RE. A frontier analysis approach for benchmarking hospital performance in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. Health Care Manag Sci 2004; 7(2): 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bayney R. Benchmarking in mental health: an introduction for psychiatrists. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2005; 11(4): 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ettorchi-Tardy A, Levif M, Michel P. Benchmarking: a method for continuous quality improvement in health. Healthc Policy 2012; 7(4): e101–e119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van Lent WAM, de Beer RD, van Harten WH. International benchmarking of specialty hospitals. A series of case studies on comprehensive cancer centres. BMC Health Serv Res 2010; 10: 253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walsh M, Laptook A, Kazzi SN, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of benchmarking and multimodal quality improvement to improve rates of survival free of bronchopulmonary dysplasia for infants with birth weights of less than 1250 grams. Pediatrics 2007; 119(5): 876–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ellershaw J, Gambles M, McGlinchey T. Benchmarking: a useful tool for informing and improving care of the dying? Support Care Cancer 2008; 16(7): 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Joint Commission Resources. Benchmarking in health care. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources, 2011, 212 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higgins I. Benchmarking in health care: a review of the literature. Aust Health Rev 1997; 20(4): 60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klazinga N, Fischer C, ten Asbroek A. Health services research related to performance indicators and benchmarking in Europe. J Health Serv Res Policy 2011; 16(Suppl. 2): 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barr TR, Towle EL. Oncology practice trends from the National Practice Benchmark, 2005 through 2010. J Oncol Pract 2011; 7(5): 286–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barr TR, Towle EL. National oncology practice benchmark: an annual assessment of financial and operational parameters-2010 report on 2009 data. J Oncol Pract 2011; 7(2 Suppl.): 2s–15s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Towle EL, Barr TR, Senese JL. The national practice benchmark for oncology, 2013 report on 2012 data. J Oncol Pract 2013; 9(6S): 20s–38s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berta P, Seghieri C, Vittadini G. Comparing health outcomes among hospitals: the experience of the Lombardy Region. Health Care Manag Sci 2013; 16(3): 245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borghans I, Heijink R, Kool T, et al. Benchmarking and reducing length of stay in Dutch hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 2008; 8: 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brucker SY, Schumacher C, Sohn C, et al. Benchmarking the quality of breast cancer care in a nationwide voluntary system: the first five-year results (2003-2007) from Germany as a proof of concept. BMC Cancer 2008; 2(8): 358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brucker SY, Wallwiener M, Kreienberg R, et al. Optimizing the quality of breast cancer care at certified German breast centers: a benchmarking analysis for 2003-2009 with a particular focus on the interdisciplinary specialty of radiation oncology. Strahlenther Onkol 2011; 187(2): 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wallwiener M, Brucker SY, Wallwiener D, et al. Multidisciplinary breast centres in Germany: a review and update of quality assurance through benchmarking and certification. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012; 285(6): 1671–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Budd HR, Almond LM, Oakley PA, et al. A benchmarking study of two trauma centres highlighting limitations when standardising mortality for comorbidity. World J Emerg Surg 2008; 3: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Templeton J, Oakley PA, MacKenzie G, et al. A comparison of patient characteristics and survival in two trauma centres located in different countries. Injury 2000; 31(7): 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coombs T, Geyer T, Pirkis J. Benchmarking adult mental health organizations. Australas Psychiatry 2011; 19(3): 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coombs T, Taylor M, Pirkis J. Benchmarking forensic mental health organizations. Australas Psychiatry 2011; 19(2): 133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coombs T, Walter G, Brann P. Overview of the national mental health benchmarking project. Australas Psychiatry 2011; 19(1): 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brann P, Walter G, Coombs T. Benchmarking child and adolescent mental health organizations. Australas Psychiatry 2011; 19(2): 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McKay R, McDonald R, Coombs T. Benchmarking older persons mental health organizations. Australas Psychiatry 2011; 19(1): 45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Mental Health Performance Subcommittee (NMHPSC). National Mental Health Benchmarking Project manual – part 1 general information for participating organisations, 2006, http://amhocn.org/static/files/assets/1859992b/Benchmarking_Manual_Part_1.pdf (accessed 15 May 2015).

- 29. Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute Liverpool (MCPCIL) and the Royal College of Physicians (RCP). National Care of the Dying Audit-Hospitals. Generic Report 2011-2012, 2012, http://www.mcpcil.org.uk/media/16537/ncdah%20generic%20report%202011-2012%20final.doc%2017.11.11.pdf (accessed 2 January 2015).

- 30. Groene O, Klazinga N, Kazandjian V, et al. The World Health Organization Performance Assessment Tool for Quality Improvement in Hospitals (PATH): an analysis of the pilot implementation in 37 hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care 2008; 20(3): 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Veillard J, Champagne F, Klazinga N, et al. A performance assessment framework for hospitals: the WHO regional office for Europe PATH project. Int J Qual Health Care 2005; 17(6): 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization (WHO). Division of Country Health Systems: performance assessment tool for quality improvement in hospitals-indicators description, Core Set, 2007, http://www.pathqualityproject.eu/upLoad/file/path_indicator_descriptions.pdf (accessed 15 December 2014).

- 33. World Health Organization (WHO). Division of Country Health Systems. Performance Assessment Tool for Quality Improvement in Hospitals-information brochure, 2007, http://www.pathqualityproject.eu/upLoad/file/brochure_providing_overview_of_the_who_path_tool.pdf (accessed 15 January 2015).

- 34. World Health Organization (WHO). Division of Country Health Systems. Performance Assessment Tool for Quality Improvement in Hospitals-Implementation Manual, http://www.pathqualityproject.eu/upLoad/file/path_implementation_manual_2006_.pdf (accessed 15 December 2015).

- 35. Mainz J, Hansen A-M, Palshof T, et al. National quality measurement using clinical indicators: the Danish National Indicator Project. J Surg Oncol 2009; 99(8): 500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mainz J, Hjulsager M, Og MTE, et al. National benchmarking between the Nordic countries on the quality of care. J Surg Oncol 2009; 99(8): 505–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCarthy M, Gonzalez-Izquierdo A, Sherlaw-Johnson C, et al. Comparative indicators for cancer network management in England: availability, characteristics and presentation. BMC Health Serv Res 2008; 8(1): 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McCarthy M, Wilkinson D, Gonzalez-Izquierdo A, et al. Measuring quality in cancer services-report for the national co-ordinating centre for NHS service delivery and organisation R&D, 2007, http://www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/64482/FR-08-1318-65.pdf (accessed 23 November 2014).

- 39. Schwappach DLB, Blaudszun A, Conen D, et al. ‘Emerge’: benchmarking of clinical performance and patients’ experiences with emergency care in Switzerland. Int J Qual Health Care 2003; 15(6): 473–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stewart FM, Wasserman RL, Bloomfield CD, et al. Benchmarks in clinical productivity: a national comprehensive cancer network survey. J Oncol Pract 2007; 3(1): 2–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gunningberg L, Donaldson N, Aydin C, et al. Exploring variation in pressure ulcer prevalence in Sweden and the USA: benchmarking in action. J Eval Clin Pract 2012; 18(4): 904–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brown DS, Aydin CE, Donaldson N, et al. Benchmarking for small hospitals: size didn’t matter! J Healthc Qual 2010; 32(4): 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brown DS, Donaldson N, Burnes Bolton L, et al. Nursing-sensitive benchmarks for hospitals to gauge high-reliability performance. J Healthc Qual 2010; 32(6): 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Collaborative Alliance for Nursing Outcomes (CALNOC). Codebook part II: data capture and submission, 2010, http://www.readbag.com/scientificplanningcommittee-wikispaces-file-view-codebook-2010partiisitev-1 (accessed 15 December 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 45. Van Lent WAM, Goedbloed N, van Harten WH. Improving the efficiency of a chemotherapy day unit: applying a business approach to oncology. Eur J Cancer 1990; 45(5): 800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Butler F. Essence of care and the pressure ulcer benchmark–an evaluation. J Tissue Viability 2008; 17(2): 44–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mello M, Cummings J. Are nurses engaged in quality initiatives? Nurs Times 2011; 107(37): 18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rogers V, Mossé P. Nursing managers between ‘governmentality’ and ‘governance’; lessons from the English experience. J Econ Med 2012; 30(6): 379–393. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Denner L. Benchmarking patient privacy to improve essence of care. Nurs Times 2004; 100(30): 36–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gibbins A, Butler J. Developing a booklet to share best practice in implementing essence of care benchmarks. Nurs Times 2010; 106(12): 10–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. National Health Service (NHS). Essence of care – complete document, 2010, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216691/dh_119978.pdf (accessed 10 January 2014).

- 52. National Health Service (NHS). How to use essence of care 2010, 2010, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216690/dh_119970.pdf (accessed 10 January 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 53. National Health Service (NHS) Modernisation Agency. Essence of care: patient-focused benchmarks for clinical governance, 2003, http://www.dignityincare.org.uk/Resources/Respecting_dignity/Autonomy/?parent=3619&;child=3561 (accessed 10 January 2014).

- 54. Comité de Coordination de l’Evaluation & de la Qualité en Aquitaine (CCECQA). Believe-restitution régionale, 2011, http://www.ccecqa.asso.fr/

- 55. Booij JC, Zegers M, Evers PMPJ, et al. Improving cancer patient care: development of a generic cancer consumer quality index questionnaire for cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2013; 13: 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hübner-Bloder G, Ammenwerth E. Key performance indicators to benchmark hospital information systems – a Delphi study. Methods Inf Med 2009; 48(6): 508–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lovaglio PG. Benchmarking strategies for measuring the quality of healthcare: problems and prospects. ScientificWorldJournal 2012; 2012: 606154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q 1966; 44(3): 166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mor V, Angelelli J, Gifford D, et al. Benchmarking and quality in residential and nursing homes: lessons from the US. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 18(3): 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Eijkenaar F. Pay for performance in health care: an international overview of initiatives. Med Care Res Rev 2012; 69(3): 251–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tu JV, Donovan LR, Lee DS, et al. Effectiveness of public report cards for improving the quality of cardiac care: the EFFECT study: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009; 302(21): 2330–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Carlisle RT. Internet report cards on quality: what exists and the evidence on impact. W V Med J 2007; 103(4): 17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M. Hospital performance reports: impact on quality, market share, and reputation. Health Aff 2005; 24(4): 1150–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wiig S, Storm M, Aase K, et al. Investigating the use of patient involvement and patient experience in quality improvement in Norway: rhetoric or reality? BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kötter T, Schaefer FA, Scherer M, et al. Involving patients in quality indicator development – a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013; 7: 259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev 2014; 71(5): 522–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]