Abstract

In methanogenic archaea, Sep-tRNA:Cys-tRNA synthase (SepCysS) converts Sep-tRNACys to Cys-tRNACys. The mechanism of tRNA-dependent cysteine formation remains unclear due to the lack of functional studies. In this work, we mutated 19 conserved residues in Methanocaldococcus jannaschii SepCysS, and employed an in vivo system to determine the activity of the resulting variants. Our results show that three active-site cysteines (Cys39, Cys42 and Cys247) are essential for SepCysS activity. In addition, combined with structural modeling, our mutational and functional analyses also reveal multiple residues that are important for the binding of PLP, Sep and tRNA. Our work thus represents the first systematic functional analysis of conserved residues in archaeal SepCysSs, providing insights into the catalytic and substrate binding mechanisms of this poorly characterized enzyme.

Keywords: SepCysS, aminoacyl-tRNA, protein synthesis

1. Introduction

Aminoacyl-tRNAs (aa-tRNAs) are utilized as substrates for protein synthesis by the ribosome [1]. Proteinogenic amino acids are normally directly attached to tRNAs by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs). However, four amino acids have been shown to lack corresponding aaRSs in certain organisms, and are thus synthesized on tRNAs via indirect pathways [2]. For example, no cognate aaRS has been found to attach selenocysteine (Sec) to tRNAs, and certain methanogenic archaea lack cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase [3,4]. In bacteria, Sec-tRNASec is converted from Ser-tRNASec (formed by seryl-tRNA synthetase) by selenocysteine synthase, while in archaea and eukaryotes, O-phosphoseryl-tRNA kinase (PSTK) first phosphorylates Ser-tRNASec to form Sep-tRNASec [5], which is then modified to Sec-tRNASec by Sep-tRNA:Sec-tRNA synthase (SepSecS) [6,7]. In methanogenic archaea, Cys-tRNACys is transformed by Sep-tRNA:Cys-tRNA synthase (SepCysS) from Sep-tRNACys, which is formed by phosphoseryl-tRNA synthetase (SepRS) [3].

SepCysS is a pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme that uses an unknown sulfur donor to convert Sep-tRNACys to Cys-tRNACys. The crystal structure of Archaeoglobus fulgidus SepCysS reveals that PLP is deeply bound at the active site near the dimer interface, and is covalently linked to Lys209 [8]. In addition, a sulfate ion is also bound at the active site, possibly mimicking the phosphate group of Sep attached to tRNACys. Functional analysis of SepCysS has been limited by the lack of a proper sulfur donor in vitro. Although it has been shown that sulfide, thiophosphate and cysteine can all be used as sulfur donors by purified SepCysS, the catalytic efficiencies using such sulfur donors are extremely low [9]. Further, in vitro purification and activity measurement of SepCysS requires stringent anaerobic conditions, making it inconvenient to employ enzymatic assays to study the function of SepCysS. Recently, an in vivo system was established to test SepCysS activity [10]. In this assay, SepCysS converts Sep-tRNASec to Cys-tRNASec in E. coli, resulting in cysteine incorporation at selenocysteine codons. This restores activity to formate dehydrogenase H (FDHH), an enzyme that requires a selenocysteine or cysteine in the active site. In this study, we combined mutational, functional, and structural modeling approaches to identify critical SepCysS residues, which is essential for understanding the substrate recognition and catalytic mechanisms of SepCysS.

2. Materials and methods

Clones and strains

Methanocaldococcus jannaschii SepCysS and PSTK were constructed into pET15b and pACYC, respectively, as previously described [6,10]. Construction of double deletion strain ΔSelA ΔSelD (MH1) was previously described [10]. M. jannaschii SepCysS mutants were obtained using site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent) and verified by DNA sequencing.

Complementation assay

The benzyl viologen assay was performed as previous reported [10]. Strains carrying SepCysS variants or empty plasmids were grown overnight in Luria Broth (LB) with 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol. 1 mL LB agar supplemented with 0.05M sodium formate, 1 μM Na2MoO4, 10 μM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside, 20 μg/mL ampicillin, and 5 μg/mL chloramphenicol, was allocated into each well of a 24-well plate. 5 μL of overnight culture were spotted at the center of each well and grown under anaerobic condition for 24–28 hours at 37 °C. Then 0.5 ml of 1% top agar with 1 mg/mL benzyl viologen, 0.25 M sodium formate, and 25 mM KH2PO4, was added on top of each well, and the purple color was developed under anaerobic condition for 1 hour. Plates were scanned and the color intensity was calculated using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc.).

Western blot of SepCysS variants

Strains carrying SepCysS variants or empty plasmids were grown in 5 ml LB for 16–18 hours. Cells were spun down, washed in 20 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.2 and lysed on ice using BugBuster protein extraction reagent (Novagen). Cell lysates were run on 12% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad), transferred to PVDF membranes by semi-dry blotting. His-tagged proteins were detected using the Amersham ECLTM Western blotting system (RPN2108).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Functional screening of conserved SepCysS residues

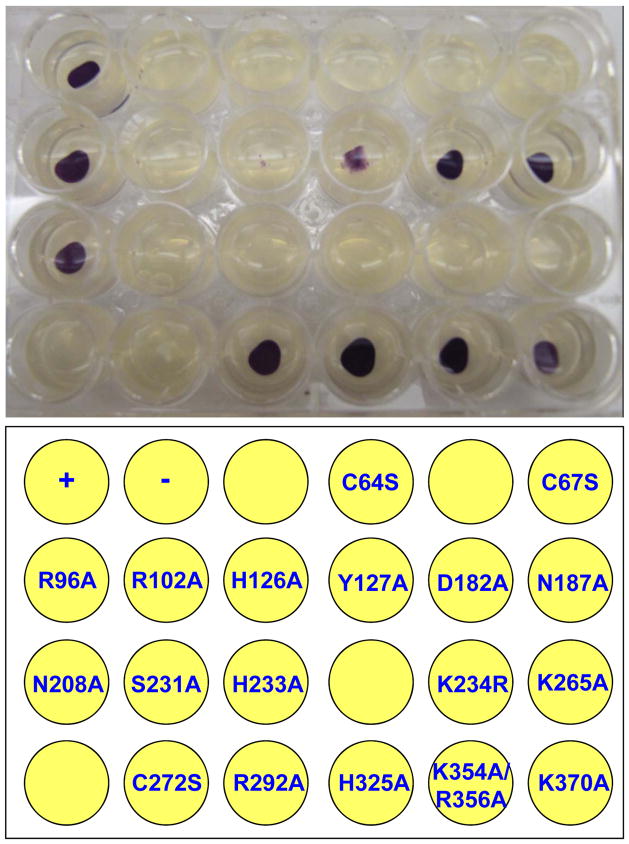

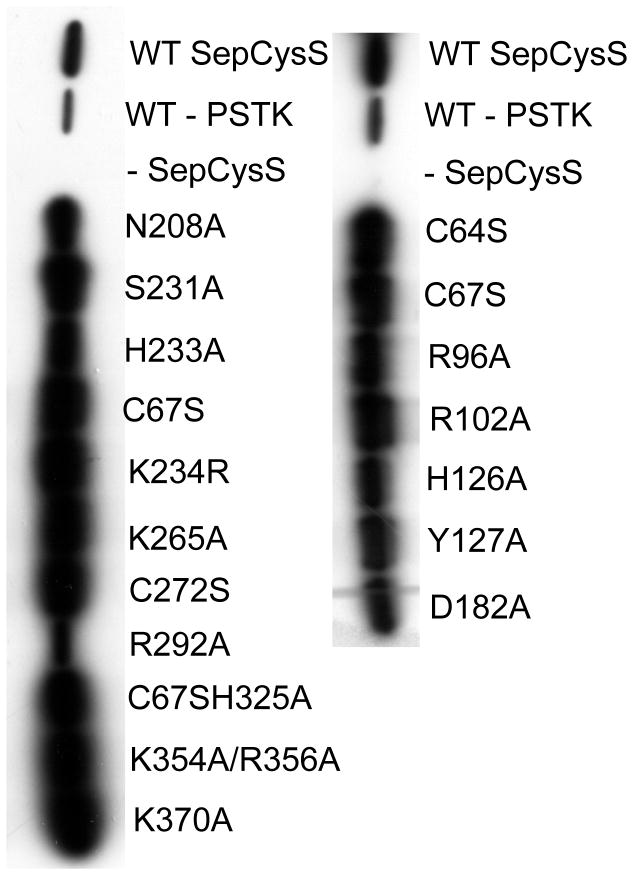

The crystal structure of AfSepCysS complexed with PLP has been solved at high resolution, yet the catalytic mechanism remains elusive due to the lack of functional studies [8]. To identify SepCysS residues that are critical for substrate binding or catalysis, we mutated 19 conserved residues located at the active site and the putative tRNA binding domain (Table 1, Fig. S1). The resulting mutants were tested in a benzyl viologen assay previously adapted to measure SepCysS activities in vivo [10]. Specifically, an E. coli ΔselA ΔselD strain, which was unable to synthesize Sec-tRNASec, was transformed with vectors expressing M. jannaschii PSTK and His-tagged SepCysS. MjPSTK recognizes E. coli tRNASec and forms Sep-tRNASec, which is then converted to Cys-tRNASec by SepCysS. In the ΔselA ΔselD strain, Cys-tRNASec restores the activity of a selenoprotein – FDHH, turning cells to purple in the benzyl viologen assay. Although this assay also requires the activity of PSTK, the SepCysS mutations are not expected to affect the production of Sep-tRNA as no interaction is required between PSTK and SepCysS. Of the 18 SepCysS variants tested, 9 showed no activity and 2 showed significantly reduced activities compared to the wild-type (WT) SepCysS (Fig. 1 and Table 1). To confirm that the SepCysS variants are expressed as soluble proteins under experimental conditions, we performed Western Blot on the cell lysate using an anti-His antibody. The WT and mutant proteins were all well expressed and soluble (Fig. 2), suggesting that the mutations introduced to SepCysS do not significantly induce protein misfolding that leads to protein degradation or aggregation. As expected, no His6-tagged SepCysS was detected in the negative control with an empty pET15b vector.

Table 1.

Activities of M. jannaschii SepCysS variants in E. coli

| Mj SepCysS | Af numbering | Relative activity | Mj SepCysS | Af numbering | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 100 ± 0 | S231A | S206 | 0 ± 0 | |

| C64S | C39 | 0 ± 0 | H233A | H208 | 0 ± 0 |

| C67S | C42 | 0 ± 0 | K234R | K209 | 0 ± 0 |

| R96A | R73 | 89 ± 27 | K265A | K240 | 0 ± 0 |

| R102A | R79 | 0 ± 0 | C272S | C247 | 0 ± 0 |

| H126A | H103 | 0 ± 0 | R292A | R267 | 99 ± 51 |

| Y127A | Y104 | 35 ± 17 | H325A | H300 | 124 ± 28 |

| D182A | D157 | 107 ± 22 | K354A/R356A | K329/R331 | 92 ± 47 |

| N187A | N162 | 85 ± 17 | K370A | K345 | 33 ± 22 |

| N208A | N183 | 101 ± 24 |

SepCysS activities were determined using a benzyl viologen assay. Relative activities were assigned to SepCysS variants based on the color intensity of three repeats with standard deviations indicated.

Figure 1. Benzyl viologen assay of M. jannaschii SepCysS variants.

The purple color indicates SepCysS activity in E. coli. +, WT SepCysS; −, no SepCysS. The experiment was repeated 3 times with a representative figure shown here.

Figure 2. Western blot analysis of SepCysS variants.

E. coli strain MH1 expressing His-tagged SepCysS variants were lysed, and SepCysS was detected with anti-His antibody.

3.2. Critical residues involved in PLP binding

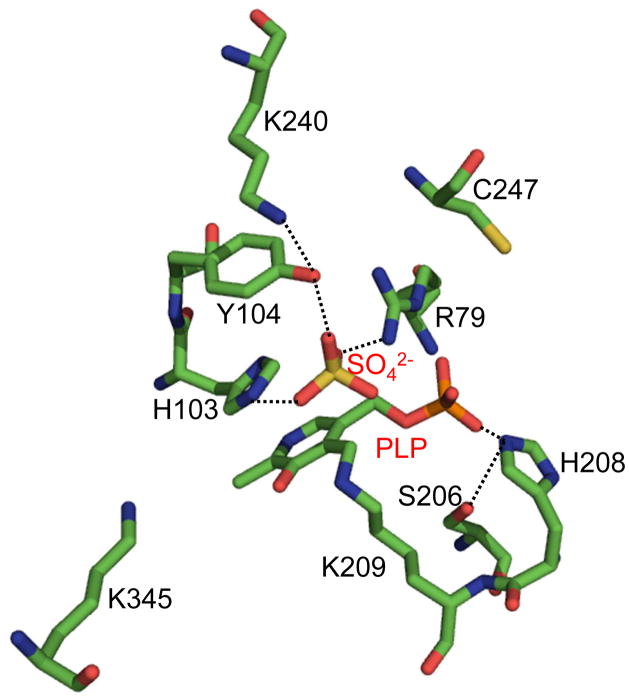

Conversion of Sep-tRNA to Cys-tRNA by SepCysS requires PLP as a cofactor. The structure of AfSepCysS [8] shows that PLP is covalently linked to Lys209 (equivalent to Lys234 in MjSepCysS, Af numbering is used below) via a Schiff base with the ε-amino group (Fig. 3). A conservative mutation of Lys209 to arginine abolished the SepCys activity in vivo (Fig. 1 and Table 1), suggesting that arginine is unable to form a Schiff base with PLP. The phosphate group of PLP forms a hydrogen bond with His208, which interacts with the hydroxyl group of Ser206. The H208A and S206A SepCysS variants showed no activity in E. coli. It is likely that His208 positions PLP in an orientation favoring Schiff base formation with Lys209.

Figure 3. Residues critical for SepCysS activity identified using in vivo screening.

The crystal structure of AfSepCysS (PDB: 2E7J) reveals that PLP is covalently linked to Lys209, and three residues coordinates a sulfate ion at the active site [8]. Our functional assay showed that Arg79, His103 and Tyr104 are all important for SepCysS activity, suggesting that these residues may interact with the phosphate group of Sep-tRNA, which is mimicked by the sulfate ion in the crystal structure. The region containing two critical residues Cys39 and Cys42 is disordered in the structure.

3.3. Role of Cys residues in sulfur donation

SepCysS contains three universally conserved cysteine residues at the active site: Cys39, Cys42, and Cys247. It has been proposed that one of these cysteines forms a persulfide intermediate that transfers a sulfur atom to the PLP-activated Sep-tRNA. Recent biochemical and mass spectrometric results suggest that the equivalent of Cys39 or Cys42 in MjSepCysS carries a persulfide group (Liu et al., manuscript submitted). Our data show that each of the conservative mutations C39S, C42S, and C247S abolishes the SepCysS activity, suggesting that all three cysteines are critical for either catalysis or substrate binding. The region containing Cys39 and Cys 42 in the AfSepCysS structure is disordered, limiting us from modeling these two residues relative to the substrate. Given the proximity of Cys39 and Cys42 in the primary structure, it is likely that both Cys residues play a role in catalysis, thus affecting the kcat value of tRNA-dependent Cys formation. The function of Cys247 remains unclear. One possibility is that Cys247 participates in the recruitment of an unknown sulfur donor; mutating Cys247 may thus affect the interaction between SepCysS and a protein sulfur donor and increase the Km level for the donor.

3.4. Binding of Sep moiety

A sulfate ion is bound to the active site in the AfSepCysS structure, likely mimicking the binding of the phosphate group of the Sep moiety. Arg79, His103, and Tyr104 all form interactions with the sulfate ion (Fig. 3). The R79A and H103A variants of SepCysS showed no activity, while the activity of Y104A reduced significantly compared with the WT. During the catalysis, the phosphate groups of PLP and Sep are simultaneously bound to the active site, accumulating substantial negative charges. The positively charged Arg79 is thus critical for neutralizing the negative charges of Sep. An unperturbed histidine side chain has a pKa of ~6.0, and is thus uncharged at neutral pH. Interestingly, the hydroxyl group of Ser105 interacts with His103, likely to increase the pKa of the imidazole ring and stabilize binding of the Sep moiety. Although we favor that Arg79, His103, and Tyr104 are required for Sep binding, we do not exclude the possibility that these residues might be involved in the binding of protein sulfur donors.

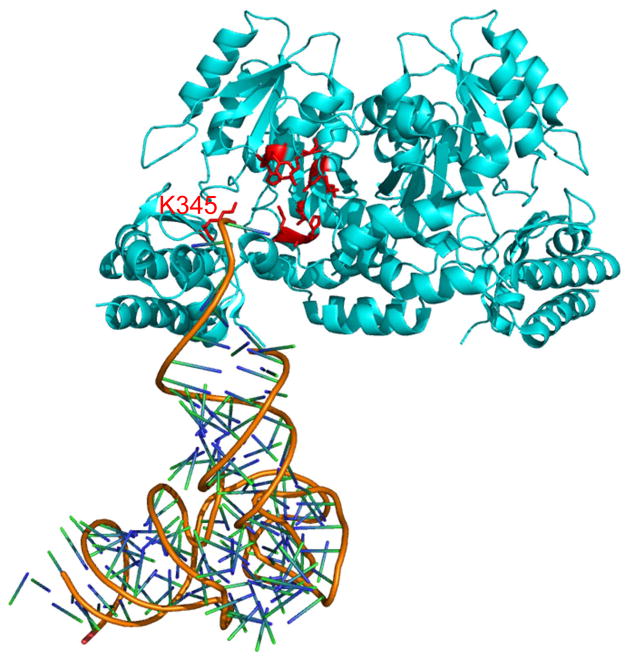

3.5. Model for tRNA binding

SepCysS recognizes three tRNACys isoacceptors and a distinct E. coli tRNASec, suggesting high plasticity in tRNA binding. To better understand substrate recognition, we constructed a docking model using the crystal structures of AfSepCysS and human SepSecS:tRNASec complex. SepCysS and SepSecS are both Fold Type I PLP-dependent enzymes, and share similar folding in tertiary structures. The docking model suggests that the 3′-CCA end, the discriminator base, and the acceptor stem of tRNASec form contacts with SepCysS, while the anticodon stem-loop and the long variable arm are distant from the enzyme. In line with this docking model, mutating Arg345 (close to the 3′-end of the tRNA) to alanine significantly decreased in vivo SepCysS activity (Table 1). It is thus likely that the major tRNA identity elements for SepCysS reside in the phosphate group of Sep and the acceptor stem. SepCysS has been shown to form a binary complex with SepRS, which improves its affinity for Sep-tRNACys [11]. SepRS recognizes the discriminator base and the anticodon loop of tRNACys [12], and thus likely discriminates against tRNASec. Nevertheless, the E. coli system we utilized does not contain SepRS, allowing tRNASec to be effectively used as a substrate by SepCysS.

3.6. Concluding remarks and future prospects

Our mutational and functional analyses in this work have revealed 11 SepCysS residues critical for catalysis and substrate binding, which is an important step for understanding the mechanism of tRNA-dependent Cys formation. Because the physiological sulfur donor remains unknown, current in vitro assays are not suitable for measuring the kinetics of SepCysS. Under our in vitro assay conditions, we are not able to detect Cys-tRNA formation by WT MjSepCysS using sodium sulfide, thiophosphate or cysteine as substrates (Fig. S2). To further dissect the roles of these residues, an efficient in vitro approach using the correct sulfur donor needs to be developed. A co-crystal structure of SepCysS complexed with Sep-tRNA is also needed to elucidate how SepCysS recognizes the substrate. Such work is expected to provide new insights into the mechanisms of Fold Type I PLP-dependent enzymes.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4. Binding model of tRNA to SepCysS.

The crystal structure of AfSepCysS (PDB: 2E7J [8]) was superimposed onto the structure of human SepSecS complexed with tRNASec (PDB: 3HL2 [13]) using PylMOL (Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.0, Schrödinger, LLC). Residue Lys345 is close to the phosphate backbone of the tRNA 3′-end and is critical for the activity of SepCysS. The Sep moiety and A76 of the tRNA are missing in the structure.

Highlights.

Mutational and functional studies identified 11 residues critical for SepCysS activity.

All three active site cysteines of SepCysS are essential for tRNA-dependent Cys formation.

The phosphate group of Sep is recognized by Arg79, His103 and Tyr104.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Michael Hohn, Yuchen Liu, Gregor Blaha, and Guđmundur Eggertsson for critical discussions and helpful insights. This project is supported by grants from the National Institute for General Medical Sciences and the Department of Energy Office of Basic Energy Sciences to DS, a Brown-Coxe Postdoctoral Fellowship to JL, and an EMBO Short Term Fellowship to SH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ibba M, Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheppard K, Yuan J, Hohn MJ, Jester B, Devine KM, Söll D. From one amino acid to another: tRNA-dependent amino acid biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1813–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauerwald A, et al. RNA-dependent cysteine biosynthesis in archaea. Science. 2005;307:1969–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1108329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambrogelly A, Palioura S, Söll D. Natural expansion of the genetic code. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:29–35. doi: 10.1038/nchembio847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bock A, Thanbichler M, Rother M, Resch A. Selenocysteine. In: Ibba M, Francklyn CS, Cusack S, editors. Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Landes Bioscience; Georgetown, TX: 2005. pp. 320–327. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan J, et al. RNA-dependent conversion of phosphoserine forms selenocysteine in eukaryotes and archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18923–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609703104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu XM, et al. Biosynthesis of selenocysteine on its tRNA in eukaryotes. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukunaga R, Yokoyama S. Structural insights into the second step of RNA-dependent cysteine biosynthesis in archaea: crystal structure of Sep-tRNA:Cys-tRNA synthase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:128–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauenstein SI, Perona JJ. Redundant synthesis of cysteinyl-tRNACys in Methanosarcina mazei. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22007–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801839200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan J, Hohn MJ, Sherrer RL, Palioura S, Su D, Söll D. A tRNA-dependent cysteine biosynthesis enzyme recognizes the selenocysteine-specific tRNA in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2857–61. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang CM, Liu C, Slater S, Hou YM. Aminoacylation of tRNA with phosphoserine for synthesis of cysteinyl-tRNA(Cys) Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:507–14. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohn MJ, Park HS, O’Donoghue P, Schnitzbauer M, Söll D. Emergence of the universal genetic code imprinted in an RNA record. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18095–100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608762103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palioura S, Sherrer RL, Steitz TA, Söll D, Simonovic M. The human SepSecS-tRNASec complex reveals the mechanism of selenocysteine formation. Science. 2009;325:321–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1173755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.