Abstract

BACKGOUND & AIMS

Activation of Fas death receptor results in apoptosis in multiple organs, particularly liver, in a process dependent on Bid cleavage. Mice injected with an anti-Fas antibody die within hours of acute liver failure associated with massive apoptosis and hemorrhage. Our aim was to investigate the crosstalk of apoptotic and inflammatory pathways and the contribution of selective hepatocellular apoptosis during in vivo Fas activation.

METHODS

We generated hepatocytes-specific Bid deficient mice (hBid−/−). Acute liver injury was induced by Fas-activating antibody (Jo2) in a time-course study.

RESULTS

In contrast to controls, Jo2 injected hBid−/− nearly all survived. Their livers showed complete protection against hepatocellular apoptosis with minimal focal hemorrhagic changes and mainly non-parenchymal cell apoptosis. In agreement, the hepatocytes had no mitochondrial cytochrome c release in cytosol, or caspase 3 activation. hBid−/− livers showed marked increase in acute inflammatory foci composed of neutrophils and monocytes associated with the increased expression of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines, in the manner dependent on noncanonical interleukin-1β activation and amplified in the absence of caspase-3 activation. In addition, hBid−/− mice were completely protected from hepatotoxicity and the infiltrated cells were cleared 2 weeks post single Jo2 injection.

CONCLUSIONS

Hepatocyte Bid suppression is critical for the resistance to the lethal effects of Fas activation in vivo. Fas signaling induces differential activation of noncanonical interleukin-1β maturation, amplified in the absence of apoptotic Bid-mitochondrial loop, in hepatocytes. These findings may have important pathophysiological and therapeutic implications in a variety of liver disorders associated with Fas activation.

Keywords: hepatoprotection, inflammation, Fas-mediated hepatic apoptosis, acute liver failure, crosstalk of inflammatory and apoptotic pathways, noncanonical IL-1β maturation

INTRODUCTION

Fas (Apo-1/CD 95) is one of the death receptors belonging to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family that are potent inducers of apoptosis and constitutively expressed in multiple tissues including the liver, spleen, thymus, heart, and lungs [1, 2]. Injection of Jo2 agonistic anti-Fas antibody to mice results in death within few hours of acute liver failure associated with marked disruption of liver architecture, massive hepatic apoptosis and gross hemorrhage [3]. Although Fas activation by the anti-Fas antibody may result in apoptotic cell death in various tissues, the lethality of this treatment has been mainly thought to be the result of acute hepatic failure secondary to massive hepatocyte apoptosis in a process dependent on Bid cleavage, a BH3-only Bcl-2 family member [4–6]. Acute inflammation and apoptosis of non-parenchymal cells of the liver have also been described [7–9]. In particular, anti-Fas antibody induced injury and apoptosis of sinusoidal endothelial cells was observed leading to the peliosis and hemorrhage in the entire liver lobule [7] and also caused rapid, extensive and disseminated endothelial cell apoptosis throughout the body [8], when the 10 and 20 μg of Jo2 anti-Fas antibody, respectively, were delivered intravenously into mice. Faouzi et al. also showed a Jo2 dose-dependent induction in hepatic chemokine production, dependent on caspase 3 activation [9].

Fas was shown to function as a link between obesity associated fatty liver and increased susceptibility to liver damage. We have previously reported that in both diet induced obesity animal model and human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis there is a significantly increased abundance of hepatic Fas, leading to increased liver sensitivity to endogenous Fas ligand [10, 11]. Pharmacologically blocking Fas signaling with an inhibitory peptide (YLGA 12-mer) reverses liver damage in two established models of fatty liver [12]. Global Bid knockout is resistant to Fas-induced hepatocellular apoptosis, gross liver hemorrhage and lethality [13]. Studies to further characterize the histopathological changes in the liver of Jo2-treated mice have shown that in addition to the well-defined massive hepatocellular apoptosis and hemorrhage, there are also significant levels of apoptosis of non-parenchymal cells of the liver, mainly sinusoidal endothelial cells and inflammatory cells [8, 14]. Furthermore, these mice show the features of acute inflammation associated with neutrophilic infiltration and increased production of certain chemokines [9]. The relative contribution of hepatocyte apoptosis versus the other lesions, and the crosstalk of apoptotic and inflammatory pathways, observed in the liver during Fas-induced liver hemorrhage in vivo remain poorly understood.

In the present study, we aimed at addressing these issues by generating hepatocyte-specific Bid knockout mice - hBid−/−. Here, we demonstrate that hepatocyte Bid is crucial for Fas-induced liver hemorrhagic changes and lethality. Furthermore, our data suggest that Fas signaling induces differential activation of noncanonical inflammatory IL-1β, TNFα, and NF-κB pathways amplified in the absence of apoptotic Bid-mitochondrial loop in hepatocytes. This study has confirmed a crucial role of hepatocyte Bid activation in Fas induced liver failure and lethality and that hepatocyte Bid-inhibition in vivo facilitates nearly full hepatic protection and leads to the complete resolution of Fas-induced inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of hBid−/− mice

Six exons were identified with the ATG start codon in exon 2 and the TGA stop codon in exon 6. We selected exons 2–4 (encoding the N-terminal 121 amino acids) as our conditional knockout (cKO) region. In the targeting vector, the Neo cassette is flanked by Frt sites and the cKO region is flanked by LoxP sites. The final vector was confirmed by both restriction digestion and end sequencing analysis. NotI was used to linearize the vector prior to electroporation into mouse C57BL/6 embryonic stem cells. Cells that have undergone homologous recombination were identified and correctly targeted clones have been confirmed. Targeted deletion of Bid in hepatocytes was created by crossing the Bid cKO with Cre recombinase expression driven by the Albumin promoter. Mouse genotypes were determined by PCR approach and confirmed by Southern blotting of genomic DNA isolated from tail biopsies. The use of Alb-Cre promoter approach also partially deletes Bid from cholangiocytes and progenitor oval cells, thus their role, although unlikely, cannot be completely excluded in this model.

Animal studies

These experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Cleveland Clinic and University of California, San Diego. All efforts were made to minimize pain and distress during animal husbandry and experimental assessments. Six to 8 weeks old hBid−/− (n = 9), Bid flox/flox albumin-cre negative (Bidfl/fl; n = 12), and wild-type C57BL/6 (WT; n = 7) mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were injected once intraperitoneally (IP) with a single dose of 100 μg anti-Fas antibody (clone Jo2; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) or vehicle (physiological saline) control. Animals were observed over 12 h for mortality and sacrificed at a point near death or at 12 h for liver histology or biochemical studies. For the time-course study hBid−/− (n = 27) mice were injected IP with 100 μg anti-Fas antibody (or vehicle controls) and sacrificed at time = 0 h (baseline), 3 h, 12 h and 2 wk. Serum samples were collected to measure ALT and AST by using a linearity test kit Infinity ALT/AST kits (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. For the low-dose Jo2 time-course study, WT (n = 12) and hBid mice (n = 12) were IP injected with 0.25 μg/g body weight of Jo2 antibody and the assessments of pathology, apoptosis, and inflammation were made at 3 h and 12 h post Jo2-injection (n = 6 at each time point). Untreated mice (n = 6, each group) were used as baseline controls.

Cell Culture and Treatment

For primary hepatocytes, WT and hBid−/− mice were perfused with collagenase D (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), described in detail in the reference [15] and digested liver was filtered on 100 μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Primary hepatocytes were isolated at 500 g for 1 min with two washes, cultured in Collagenase I coated dish for 3 hours in William E medium-10% FBS and further cultured for 8 hours in serum free William E medium. Primary hepatocytes were treated with 10 ng Jo2 antibody/ml media and the assessments of cell death/apoptosis and inflammation were made at 1 h, 3 h, and 12 h post jo2-treatment (n = 6 at each time point). Untreated primary hepatocytes were used as baseline controls. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were cultured in DMEM-10% FBS. To initiate necrosis, MEFs were pre-incubated for 1 h in 20 μM Z-VAD-FMK (global caspase inhibitor) and 1 μg/ml cycloheximide, and treated with 100 ng/ml of TNFα for additional 5 h.

Histology, Apoptosis assessment, Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Livers were weighted, cut into small pieces and fixed in 10% formalin up to 24 h. After wash and dehydration, livers were paraffin embedded and cut (4 μm) by the UCSD Histology core. Haematoxylin and eosin stained sections were used for histopathological evaluation of hepatic injury. Assessment of apoptosis were performed by terminal desoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick and labeling (TUNEL) staining with ApopTag peroxidase in situ apoptosis detection kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) on paraffin-embedded liver specimens and DeadEnd Fluorometric System (Promega, Madison, WI) on frozen sections according to the manufacturer instructions. TUNEL positive nuclei were quantified by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). In primary hepatocyte, cell death/apoptosis was assessed by 1) measuring the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in cell culture media via CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega), 2) assessing caspase 3 activity via Apo-ONE® Homogenous Caspase 3/7 assay, and 3) LIVE/DEAD® Cell Viability Assay (Invitrogen/Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Immunostaining for cleaved caspase 3 (apoptosis; Cell Signaling; 1:250), CD31 (marker of endothelial cells; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 1:50), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2 (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC; 1:50), myeloperoxidase (MPO; marker of neutrophils; Abcam; 1:50), CD3 (marker of T-cells; Abcam; 1:50), and F4/80 (marker of mouse macrophages; AbD Serotec; 1:50) were performed according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Necrosis was assessed by co-localization of kinase receptor-interacting protein (RIP)-1 (BD Transduction Laboratories; 1:50) and RIP-3 (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA; 1:50) with Alexa Flour 488 and 594 (Life Technologies), as secondary antibodies, by immunofluorescence on frozen sections as previously described [16]. Treated MEFs were incubated with RIP-1 and RIP-3 antibodies as described above. All pictures were taken by NanoZoomer 2.0HT Slide Scanning System (Hamamatsu, Japan).

Western blots

Whole cell liver lysates were digested in RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tables (Roche). Liver lysates were continuously rotated for 30 min at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Liver lysates (80 μg) were resolved by Criterion™ TGX Any kD™ Precast Gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were transferred to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) and blocked for 1 h with 5% non-fat milk or bovine serum albumin in TBS, 0.05% Tween 20. Blots were then hybridized overnight using antibody specific for total caspase 8, cleaved caspase 8 (D387), total caspase 3, cleaved caspase 3 (D175), phospho-NF-κB, interleukin (IL)-6 (all: Cell Signaling; 1:1000), and Fas receptor/CD95 (GeneTex, Irvine, CA; 1:1000). Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractionation was performed by Mitochondrial Isolation kit for tissues (Thermo Scientific), proteins were transferred to membranes as above and hybridized overnight using anti-cytochrome c antibody (136F3; Cell Signaling; 1:1000). Nuclear and cytosolic fractionation was performed by NE-PER® Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Scientific). Actin (Santa Cruz; 1:1000), porin (VDAC1; Abcam; 1:1000), and p84 (GeneTex; 1:1000) were used as loading controls for the whole liver lysates/cytoplasmic fraction, mitochondrial fraction and nuclear fraction, respectively. For the time-course study (with the high Jo2 dose), cell lysates were made from isolated hepatocytes (or whole liver lysates at 2 wk) following the same protocol as above and proteins were hybridized using antibody specific for IL-1β (Abcam; 1:1000). Antibodies used to test selectivity and specificity of Bid absence were specific for mouse Bid, Bax and BAD (Cell Signaling) and Bcl-Xl (BD Biosciences). Secondary antibody used was anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling; 1:5000). Proteins were visualized by SuperSignal West chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce Biotechnology) and quantified by ImageJ software.

Gene expression

Liver tissue (or isolated hepatocytes for the time-course study) from WT and hBid−/− were homogenized using the FastPrep 24 bead homogenization system (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA). Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reverse transcribed by iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity of RNA was assessed by NanoDrop (Thermo scientific). Housekeeping genes GAPDH or B2M were used as an internal control. The PCR primers used to amplify each gene are listed in Supplement Table 1. Quantitative Real-time PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad Cycler (Bio-Rad) by using SYBRGreen real time PCR master mix (KapaBiosystems, Woburn, MA).

Flow cytometry

Livers were perfused with PBS and force filtered through a 100 μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences). Whole liver cell suspensions were incubated with RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), washed with PBS-3% FBS and a small fraction was first analyzed with CD45 (BD Biosciences) or Ly6G (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) antibodies by flow cytometry to assess the specificity of infiltrated cells in the entire liver. Next, to separate infiltrated cells, whole liver cell suspensions were centrifuged at 50 g for 1 min to remove hepatocytes. Infiltrated cells were further purified by Polymorphprep™ (CosmoBio USA, Carlsbad, CA) and layers of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells were recovered, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified infiltrated cells were incubated with RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience), washed with PBS-3% FBS, incubated with antibody cocktail, FITC-CD45 (BD Biosciences), Alexa405-CD11b (eBioscience), PEcy5.5-Ly6G (Biolegend), PE-ICAM (BD Biosciences) for 30 min on ice, and washed with PBS-3% FBS. For each time point the data obtained from Jo2-treated hBid−/− mice (n = 4) were corrected to data from saline-treated hBid−/− mice (n = 3). All cell suspensions were analyzed by Flow cytometer, BD LSR II (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed by FlowJo software.

Data analysis

Two-tailed Student t-test and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test were used for analyzing qPCR data and survival rate, respectively, when comparing two groups. For multiple-comparison tests, data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni Post-hoc test among groups at each time point. Data are reported as mean ± SEM, with significance at P < 0.05. GraphPad software (La Jolla, CA) was used to perform analyses and to construct graphs.

RESULTS

Hepatocyte-specific Bid-deficiency mediates in vivo resistance to Fas-induced mortality, hepatocyte apoptosis, gross liver hemorrhage, and marked neutrophilic infiltration in the livers of hBid−/− mice

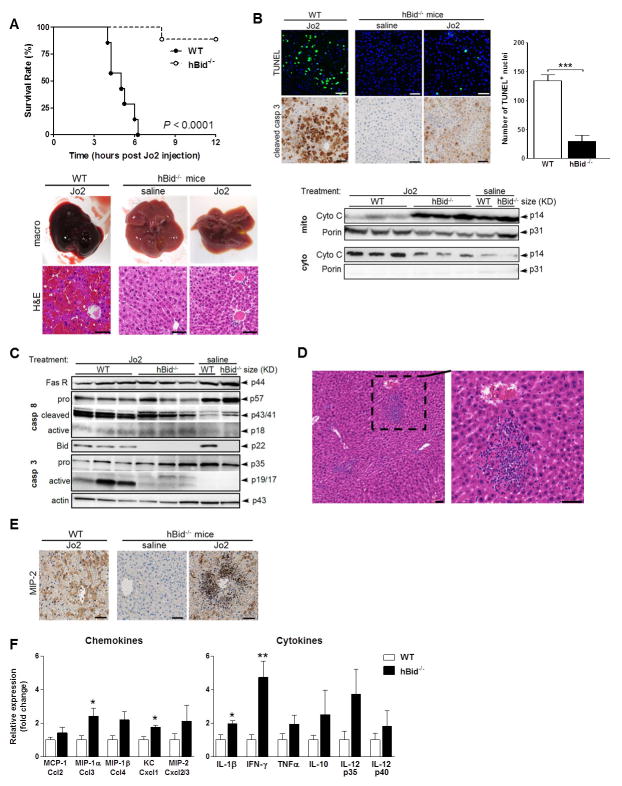

To assess the role of selective hepatocyte apoptosis during Fas activation in vivo, we generated a hepatocyte-specific cKO model of the mBid gene using the cre/loxP system (Supplement Fig. 1A). Bidfl/fl mice were born at the expected mendelian frequency, had no apparent developmental abnormalities, and had normal spleens, thymuses, brains, hearts, livers, lungs, kidneys and testes with respect to weight and histology. The selective and specific absence of Bid expression in hepatocytes in albumin-Cre Bid flox/flox (hBid−/−) was demonstrated by immunoblotting. No changes in the abundance of other pro- or anti-apoptotic proteins (Bax, Bad, or Bcl-Xl) in the liver, kidney, spleen, or thymus were detected (Supplement Fig. 1B). To investigate the role of Bid in hepatocyte apoptosis, hemorrhagic response, hepatic failure and lethality, mice were injected IP with 100 μg of anti-Fas antibody (clone Jo2), as it was done previously to challenge global Bid knockout [3]. All WT mice, as well as albumin-cre negative Bidfl/fl controls, died within the first 3 to 6 hours (mean survival time – 5 and 4.7 hours, respectively) of acute liver failure associated with marked disruption of liver architecture, massive hepatic apoptosis and gross hemorrhage (Fig. 1A; Supplement Fig. 1C). In sharp contrast, most hBid−/− mice (8 out of 9) survived the high-dose (100 μg) of anti-Fas antibody injection (Fig. 1A). Histopathological examination of hBid−/− livers demonstrated nearly complete protection against hepatocellular apoptosis with intact cell nuclei, minimal focal hemorrhagic changes, similarly to the phenotype of hBid−/− physiological saline (vehicle) injected controls (Fig. 1A). The low mortality in hBid−/− mice and the remaining hepatocyte apoptosis is likely due to variable penetrance of cre/loxP approach and/or the activation of alternative apoptotic mechanisms independent of Bid activation, as previously described [13].

Figure 1. hBid−/− mice are resistant to Fas-induced mortality, hepatocyte apoptosis and gross liver hemorrhage, but are prone to the formation of marked acute inflammatory foci and neutrophilic infiltration.

(A) Survival curve of wild-type (WT; filled circles, n = 7) and hBid−/− mice (circles, n = 9) in response to a single IP injection of 100 μg Jo2 over the period of 12 h post injection, P < 0.0001. Mice were sacrificed 12 h after Jo2-injection or shortly before death. Liver macro pictures and haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections of Jo2 injected WT mice and vehicle control (saline) or Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice, respectively. Note the marked disruption of liver architecture, massive hepatic apoptosis and gross hemorrhage due to Fas activation in WT mice. (B) DNA fragmentation by TUNEL assay and detection of apoptosis by immunohistochemical staining specific for cleaved caspase 3 in WT and vehicle control or Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice. Quantification of the representative 40x TUNEL fields of WT (n = 7) vs. hBid−/− (n = 5) mice. Assessment of cytochrome c distribution in mitochondria vs. cytosol of fractionated liver lysates in WT and hBid−/− mice. (C) Analysis of the activation of initiator caspase 8 and effector caspase 3 in livers by immunoblots after injection of Jo2 in WT and vehicle control or Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice. Representative blots show the activated fragments: p18 of caspase-8 and p17/19 of caspase-3, in addition to their pro-caspase counterparts. (D) Haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections of Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice, emphasizing neutrophilic infiltration; (E) immunohistochemical staining specific for MIP-2 in WT and vehicle control or Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice. Note the marked neutrophilic infiltration and the concomitant focal increase in the abundance of MIP-2 in hBid−/− compared to WT mice. (F) Expression profiling of chemokines and cytokines involved in Fas-mediated liver inflammation. All animals (n = 4, each group; WT, open bars; hBid−/−, black bars) were injected with Jo2. All gene expression levels are shown relative to the expression levels of WT mice. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to controls. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Acute liver failure in WT mice was associated with marked increase in cellular death coupled with activation of the initiator caspase 8 and the effector caspase 3, as evidenced by TUNEL assay, immunohistochemical staining, immunoblotting, and a notable redistribution of cytochrome c into the cytosol (Fig. 1B, C). In contrast, there was significantly less TUNEL-positive nuclei in hBid−/− livers and cytochrome c was mostly contained in mitochondria in hBid−/− mice compared to WT controls (Fig. 1B). Despite the similar level of caspase 8 activity in WT and hBid−/−, there was a significant absence of the active, cleaved fragment of caspase 3 in the livers of hBid−/− mice compared to WT (Fig. 1C). Moreover, massive apoptosis of both hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells with neutrophil infiltration was demonstrated in Bidfl/fl controls with immunohistochemical serial liver sections stained against antibody markers of endothelial cells (CD31), neutrophils (MPO) and TUNEL (Supplement Fig. 2B). In contrast, serial liver sections stained with the same set of markers showed that hBid−/− mice were protected from both hepatocyte and sinusoidal endothelial cell death, and that most of the TUNEL-positive nuclei co-localized with infiltrated neutrophil foci (Supplement Fig. 2B).

Despite diminished hepatocyte apoptosis, livers from anti-Fas antibody treated hBid−/− mice showed a plethora of marked acute inflammatory foci composed predominantly of neutrophils and monocytes, as demonstrated by MPO immunohistochemical staining and histopathological examination (Fig. 1D and Supplement Fig. 2A, B). In addition to the presence of apoptotic neutrophils, this pattern was also associated with increased focal abundance of MIP-2 (a murine IL-8 analog; Fig. 1E) and increased expression of other chemokines often associated with hepatic inflammation, such as MIP-1α and KC (P < 0.05), as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β (P < 0.05) and interferon (IFN)-γ (P < 0.01; Fig. 1F). There were no significant changes in expression of these genes between saline treated WT and hBid−/− controls (data not shown).

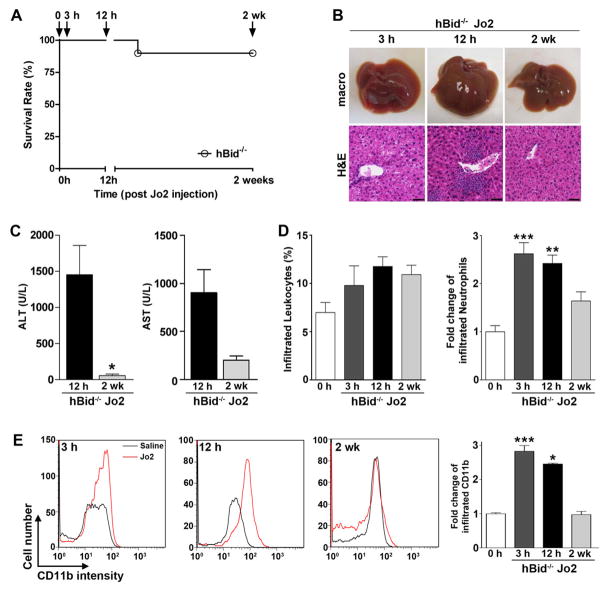

Bid-deficiency facilitates hepatic protection and leads to the complete resolution of inflammation two weeks post anti-Fas antibody injection

We performed a time-course study to assess the extent of protection resulting from hepatocyte-specific Bid-deficiency. This study showed almost complete protection from lethality (90% survival rate), hepatocyte apoptosis and liver hemorrhage over the two week period post single high-dose (100 μg) anti-Fas antibody injection in hBid−/− mice (Fig. 2A, B). While neutrophils have previously been described as playing a main role in acute inflammatory liver injury and leading to hepatocellular death [17], in Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice they remained confined to inflammatory foci in the acute phase (12 hours post injection) and ultimately returned to near normal levels two weeks post injection (Fig. 2B). Correspondingly, the serum levels of ALT and AST returned from supraphysiolocgical levels at 12 hours to normal levels two weeks post Jo2 injection (Fig. 2C). Flow cytometry analysis showed the percentages of infiltrated leukocytes, especially the fold increase of neutrophils, into the liver were acutely increased at 3 and 12 hours post Jo2 injection, with almost complete resolution of inflammation two weeks post injection (Fig. 2D). In detailed flow cytometry analysis using purified infiltrated cell population, monocyte infiltration was also shown to be dramatically increased at 3 and 12 hours post injection (Fig. 2E). Notably, monocyte infiltration was completely recovered to baseline levels at 2 weeks post Jo2 injection (Fig. 2E). Similar trend was observed with ICAM+ cells (a marker of eosinophils; Supplement Fig. 3A). There was no apparent difference in the abundance in T-lymphocytes (CD3+ cells) and mature macrophages (F4/80+) at any of the time points, as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry (Supplement Fig. 3B).

Figure 2. Time-course study: resistance of hBid−/− mice to Fas-induced mortality and the complete resolution of inflammation two weeks post anti-Fas antibody injection.

(A) Survival curve of hBid−/− mice (n = 10) in response to a single IP injection of 100 μg anti-Fas antibody (Jo2) over the period of 2 weeks. (B) Liver macro pictures and haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections of hBid−/− mice post Jo2-injection. (C) Plasma levels of ALT and AST of hBid−/− mice 12 h and 2 wk post Jo2-injection (hBid−/− n = 4). (D) Percent of leukocytes and fold change of neutrophils (respective to saline injections at each time point) infiltrated into the liver of hBid−/− post Jo2-injection by flow cytometry analysis. (E) Representative histograms of infiltrated monocytes (CD11b+). Red line: hBid−/− Jo2 injection, Black line: hBid−/− saline injection. Bar graph shows quantification of infiltrated cells as shown by fold change compared to saline injections at each time point. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to baseline controls. Scale bar, 50 μm.

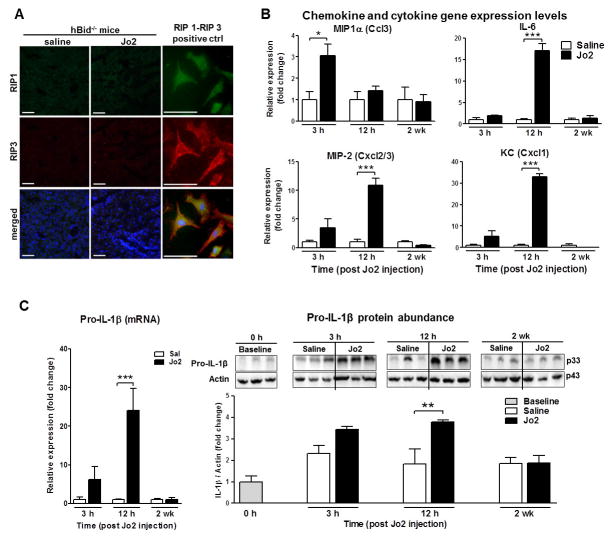

In hBid−/− mice Fas mediates inflammation via hepatocyte chemokine and IL-1β production in RIP-independent manner

In the time-course study we sought to characterize the mechanisms of Fas-induced inflammation and its resolution. We demonstrated by fluorescent immunohistochemical staining of hBid−/− liver sections that Fas stimulation does not induce activation of either RIP-1 or RIP-3, or does not lead to the in vivo formation RIP-1/RIP-3 complex 12 hours post Jo-2 injection (Fig. 3A), shown to be necessary for the initiation of programmed necrosis [18]. Positive control for immunofluorescent assay and the formation of RIP-1/RIP-3 complex was performed in mouse embryonic fibroblast cells, as described in the methods (Figure 3A). Furthermore, in isolated hepatocytes, we showed that there was a significant increase of MIP-1α expression levels (P < 0.05) 3 hours post Jo2 as compared to saline control treated hBid−/− mice, as well as MIP-2, IL-6, and KC (all P < 0.001) 12 hours post Jo2-treatment (Fig. 3B). It has recently been shown that these chemokines, in particular IL-8 (murine MIP-2), may serve as “find-me” signals for apoptotic cells and play essential role for migration of human neutrophils toward dying cells [19]. In addition, we showed that there is a significant increase in hepatocyte pro-IL-1β gene expression, followed by the increase in hepatocyte pro-IL-1β protein abundance at 12 hours post Jo2-injection (P < 0.01; Fig. 3C). Corresponding to the resolution of inflammation, levels of chemokines and cytokines were normalized at 2 weeks post Jo2-injection (Fig. 3B, C).

Figure 3. Time-course study: Fas mediates hepatocyte chemokine and IL-1β production in an RIP-independent manner.

(A) Hepatic Fas signaling does not induce RIP-1/RIP-3 complex required for programmed necrosis 12 h post Jo2-injection. Immunofluorescent staining specific for RIP-1 and RIP-3 kinases and merged image in vehicle and control Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice. Necrotic MEFs were used as a positive control for the formation of RIP-1/RIP-3 complex. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Hepatocyte (at 3 h and 12 h) and whole liver (at 2 wk) chemokine gene expression levels in Fas-mediated liver inflammation of hBid−/− mice. Gene expression was measured in hBid−/− mice (n = 3, each group; saline, open bars; Jo2 treated, black bars) 3 h, 12 h and 2 wk post Jo2 injection. All gene expression levels were normalized to housekeeping control and shown relative to the expression levels of saline treated mice. (C) Hepatocyte pro-IL-1β gene expression and protein levels post Jo2-injections in Fas-mediated liver inflammation of hBid−/− mice (saline, open bars; Jo2 treated, black bars). Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to controls.

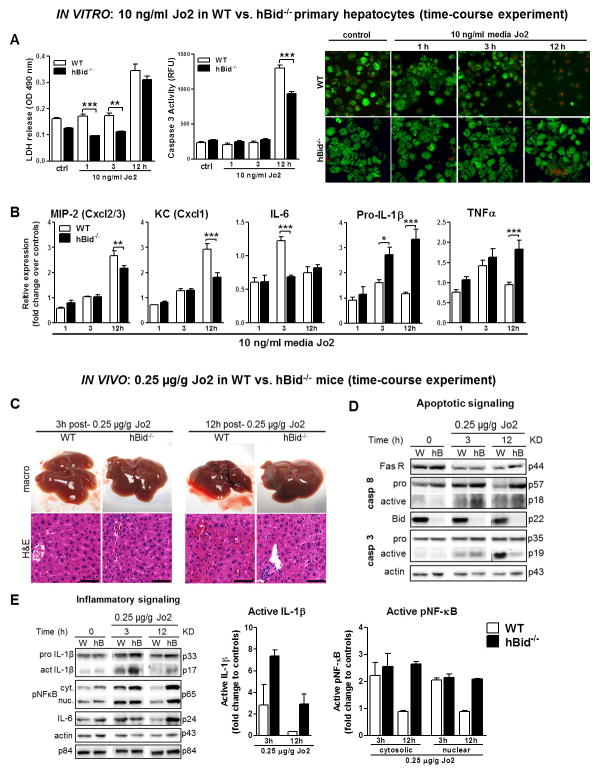

Low dose Jo2 treatment of hBid−/− primary hepatocytes and mice demonstrates that Fas mediates inflammation via the activation of noncanonical IL-1β/TNFα and NF-κB pathways amplified in the absence of apoptotic Bid-mitochondrial loop

By introducing a low-dose Jo2 time-course treatment in WT and hBid−/− primary hepatocytes and mice we aimed at determining the relationship between inflammation and apoptosis, the mechanisms involved, and the hepatocyte-specific contribution. In order to determine the lowest dose of Jo2 antibody to induce minimal apoptosis and still activate chemokine and cytokine production, we performed in vitro and in vivo Jo2 dose response experiments in primary WT hepatocytes (Supplement Fig. 4A, B) and WT mice (Supplement Fig. 4C, D). Based on these experiments, we decided to use a low-dose of 10 ng Jo2 antibody/ml cell media for the in vitro study and 0.25 μg Jo2/g mouse body weight for the in vivo study. The levels of apoptosis and inflammation were assessed at baseline (untreated controls), 1 h, 3 h and 12 h post Jo2-treatment in primary hepatocytes extracted from WT and hBid−/− mice. hBid−/− primary hepatocytes showed marked protection from apoptosis as shown by reduced lactate dehydrogenase release and caspase 3 activity, and live/dead cell viability assay as compared to WT primary hepatocytes treated with 10 ng Jo2 antibody/ml media (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, MIP-2 (P < 0.01 at 12 h), KC (P < 0.001 at 12 h), and IL-6 (P < 0.001 at 3 h) were significantly higher in WT primary hepatocytes parallel to the amount of apoptosis (Fig. 4B). Remarkably, the expression levels of IL-1β (P < 0.05 at 3 h and P < 0.001 at 12 h) and TNFα (P < 0.001 at 12 h) were significantly higher in hBid−/− primary hepatocytes, suggesting that these genes were up-regulated via Fas signaling in the absence of caspase-3 activation (Fig. 4B). The upregulation of these genes was concomitant to the increased NF-κB activation in hBid−/− as copared to WT primary hepatocytes (Supplement Fig. 5). To investigate the crosstalk of apoptotic and inflammatory pathways in vivo we exposed the WT and hBid−/− to a low dose of Jo2 antibody and monitored apoptotic and inflammatory signals at baseline (untreated controls), 3 h and 12 h post Jo2-injection. All mice lived to 12 h without apparent physiological trauma. Histopathological examination of livers demonstrated moderate levels of liver hemorrhage in WT mice at 12 h post Jo2 (but significantly less hemorrhage that was caused by a high dose of Jo2), and the formation of focal inflammatory points in hBid−/− mice at 12 h as previously shown with high Jo2 concentration (Fig. 4C). Similarly to mice treated with high dose of Jo2, there was a significant absence of the active, cleaved fragment of caspase 3 in the livers of hBid−/− mice compared to WT mice at 12 h (Fig. 4D). Remarkably, there was an increase in the active IL-1β fragment abundance especially at 3 h post Jo2-injection (7-fold over the control) and increased IL-6 levels at 12 h corresponding to the marked abundance of phosphorylated NF-κB in both nuclear and cytosolic fractions of the livers of hBid−/− mice (Fig. 4E). Both in vitro and in vivo data strongly suggest that Fas may induce differential activation of alternative inflammatory IL-1β, TNFα, and NF-κB pathways amplified in the absence of apoptotic Bid-mitochondrial loop (Supplement Fig. 6).

Figure 4. In vitro and in vivo low Jo2 dose time-course study dissociates apoptotic and inflammatory pathways.

(A) The assessment of apoptosis and cell death in WT (open bars) and hBid−/− (black bars) primary hepatocytes. From left to right, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assay, caspase 3 activity and live/dead cell viability assay (red stains nuclei of dead cells, green stains living cells). (B) Hepatocyte inflammatory chemokine and cytokine gene expression normalized to untreated controls (n=6 each group). (C) Liver macro pictures and haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections of Jo2 injected WT (open bars) and hBid−/− mice (black bars). Note the small levels of liver hemorrhage in WT and the formation of inflammatory foci hBid−/− mice at 12 h post Jo2 injection. (D) Representative immunoblots of select apoptotic signaling pathways in Jo2 injected WT and hBid−/− mice. (E) Representative immunoblots and protein levels of select inflammatory signaling pathways probed in cytosolic (cyt.) and nuclear (nuc.) fractions. Note the marked abundance of mature/active IL-1β at 3 h and sustained activation of NF-κB and the corresponding abundance of IL-6 through 12 h post Jo2-treatment in hBid−/− mice. W, WT; hB, hBid−/−. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to controls. Scale bar, 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Fas (Apo-1/CD 95), a death receptors belonging to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family, was shown to function as a link between steatohepatitis and hepatocellular damage. In our present study we generated hepatocyte-specific Bid deficient mouse to investigate the role of selective hepatocyte apoptosis during Fas activation in vivo, a model of acute liver injury. Here, we clearly demonstrate that hepatocyte Bid is crucial for Fas-induced liver hemorrhagic changes and lethality and show dissociation between hepatocyte apoptosis and inflammation. We also reveal that inflammatory cells by themselves cannot induce liver failure, even though abundant inflammatory cells acutely and focally infiltrated into the liver via Jo2 injection. When hepatocytes were protected from apoptosis, we found a near complete recovery of liver function and the resolution of inflammation two weeks post Jo2 injection.

Fas-induced apoptosis has been postulated as a model of pro-inflammatory apoptotic cell death [20–22]. However, the role the cell-specific and molecular mechanisms linking hepatic apoptosis and inflammation during systemic administration of an anti-Fas antibody has not been characterized, partially due to the lack of adequate in vivo models and specific caspase inhibitors. While Faouzi et al. showed that caspase 3 inhibition reduced chemokine induction and neutrophilic infiltration in Jo2-treated livers [9], it has later been shown that the caspase 3 inhibitor used in this study (Z-DEVD-FMK) was also partially inhibiting caspase 8 [23], as well as other caspases, thus bringing the conclusion that inflammatory response is dependent on caspase 3 activation and apoptosis into question. In hBid−/− mice we observed marked neutrophilic infiltration to the liver, suggesting that inflammatory pathway may be activated in parallel and differentially to apoptotic pathway.

As shown by Faouzi et al. [9] we confirmed that common neutrophilic chemokines, MIP-2 and KC, and cytokine IL-6, increased their expression level in parallel to the amount of apoptosis in primary WT hepatocytes. However, we identified that a noncanonical pathway for IL-1β and TNFα expression was significantly increased in hBid−/− compared to WT hepatocytes. Furthermore, our in vivo studies with a low dose of Jo2 demonstrated that there is a significant increase in the noncanonical IL-1β maturation and higher abundance of phosphorylated, active NF-κB with the sustained presence in both nuclear and cytosolic fraction in the livers of Jo2-injected hBid−/− compared to WT mice over a 12 h time-course. These data are supported by the findings of Bossaller et al., where it has recently been shown that Fas mediates noncanonical IL-1β maturation via caspase 8 in an RIP-3-independent manner in macrophages [24]. In agreement with these findings, we observed the similar alternate activation and maturation of IL-1β in the hepatocytes, in a manner dependent on caspase 8 activation, independent of RIP-1 and -3 activity and co-localization, and amplified in the absence of caspase 3 activation 12 hours post single Jo2-injection. Although RIP-1 kinase has been shown to be recruited to the Fas Death-inducing signaling complex and necessary for the optimal production of cytokines and chemokines in response to Fas receptor stimulations, its recruitment and role has been shown to be minimal in the cells with functioning caspase 8 [19], or cells stimulated with anti-Fas antibody [25]. In summary, these data suggest that Fas signaling induces differential activation of noncanonical inflammatory IL-1β, TNFα, and NF-κB pathways amplified in the absence of apoptotic Bid-mitochondrial loop in hepatocytes.

Most of the non-hepatocytes are the so-called type I cells, where Fas-induced death is not dependent on Bid signaling and mitochondrial amplification [13], and thus inhibiting Bid in these cells might not play a crucial protective role, but rather lead to delayed or attenuated apoptotic response. However, hepatocytes are generally considered to be type II cells (where Bid and mitochondria are necessary to amplify apoptotic signal) because global Bid knockout mice were reported to be resistant to hepatocyte apoptosis upon Fas activation [13, 26]. However, more recent studies have challenged this view. It has been shown that the high-dose of hexameric Fas ligand (a more potent activator of Fas receptor [27]) or double Bak/Bax deficiency [28] may lead to circumvention of mitochondrial apoptotic pathways and activation of type I pathway in the hepatocytes, where caspase 8 directly activates caspase 3 and induces apoptosis. However, while we used relatively high dose of Jo2 antibody in this study (~5 mg/kg), we have not seen a significant activation of apoptotic pathways in hBid−/−. In addition, in contrast to double Bak/Bax knockout mice, by specifically deleting Bid from hepatocytes there was no delayed-onset hepatocyte apoptosis as evidenced by our two week time-course study. Furthermore, although Liedtke et al. have previously reported that the hepatocyte-specific deletion of caspase 8 protected from Fas-induced lethality, this model also unexpectedly triggered increased non-apoptotic liver injury and oxidative stress [16]. Another group demonstrated that caspase 8 activation is crucial to inhibit the interaction of RIP-1 and -3 which complex formation has been shown to be required for initiation of programmed necrosis [18]. In agreement, we demonstrated that hepatocyte-specific deletion of Bid, which does not interfere with Fas-induced caspase 8 activation, did not induce programmed necrosis. Taken together, these results suggest that Bid, as opposed to its upstream (caspase 8) or downstream (Bak/Bax) counterparts, is the ideal target to inhibit apoptotic pathway and reduce hepatic stress.

The engagement of Fas leads to the activation of caspase 8 by cleaving the large cytosolic Bid to its active, truncated form, tBid, which in turn translocates into the mitochondrion as an integral membrane protein [29, 30]. tBid is a key component required for the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria [31, 32]. Cytosolic cytochrome c binds to apoptosis activating-factor 1, a scaffolding protein that facilitates activation of procaspase 9. Once activated, caspase 9 cleaves caspases 3 and 7, resulting in their activation and subsequent stereotypic apoptotic events [33, 34]. Our hepatocyte specific Bid-deficient mice demonstrate that activation of Bid in hepatocytes and selective hepatocellular apoptosis is a critical event leading to the lethality induced by Fas activation in vivo. Indeed, in striking contrast to WT animals or Bidfl/fl controls, hBid−/− mice were almost completely resistant to the mortality resulting from systemic anti-Fas antibody administration. Second, our data clearly demonstrate the importance of hepatocyte apoptosis in the hemorrhagic changes typically observed in the livers of anti-Fas antibody injected animals. In the past, these changes were proposed to be the consequence of apoptosis of sinusoidal endothelial cells of the liver which are known to express Fas and to be sensitive to Fas ligation in vivo. However, the fact that the lack of hepatocyte apoptosis in the hBid−/− mice led to marked protection from Fas-induced liver hemorrhage, suggests that the hemorrhage and lethality are the consequences of the massive distortion of the liver architecture resulting from the hepatocyte apoptosis, rather than the apoptosis of sinusoidal endothelial cells, and that sinusoidal endothelial cells entail stronger resistance to Fas-induced apoptosis. Current studies also showed that inhibition of hepatocyte apoptosis in the hBid−/− mice was in fact associated with marked increased in chemokine and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in the liver, in particular the activation of noncanonical IL-1β maturation, resulting in acute inflammatory infiltrates composed mainly of neutrophils and monocytes. These data strongly suggest that although hepatocyte apoptosis and liver inflammation occur in parallel during Fas engagement, they are differentially regulated. In summary, our results from hepatocyte specific deletion of Bid indicate that hepatocyte apoptosis is the crucial event for the lethal effects of Fas engagement in vivo. These results may have important pathophysiological and therapeutic implications in a variety of liver disorders associated with Fas activation.

Supplementary Material

Supplement Figure 1. Creation of hBid−/− mice by gene targeting and the comparable sensitivity to anti-Fas antibody in albumin cre negative Bid flox/flox control mice. (A) Vector construct strategy. Diagram of the Bid genomic locus and the homologues recombinant. Indicated are the restriction enzyme sites (B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII). Arrowheads labeled a, b and c indicate the positions of primers used in screening genotypes by PCR. (B) Western blot demonstrating the absence of Bid protein in hBid−/− albumin cre positive mice specifically in liver, but not in other organs. There were no changes in the abundance of other pro- or anti-apoptotic proteins belonging to the Bcl-2 family (Bcl-Xl, Bax and BAD). (C) Survival curve of WT mice (filled circles, n = 7) and albumin cre negative bid flox/flox mice (Bidfl/fl; triangles, n = 12) in response to a single IP injection of 100 μg anti-Fas antibody (Jo2) over the period of 12 hours post injection. Liver macro pictures and haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections of Jo2 injected WT and Bidfl/fl mice, respectively. Note the marked disruption of liver architecture, massive hepatic apoptosis and gross hemorrhage due to Fas activation in both WT and Bidfl/fl mice mice. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Supplement Figure 2. Hepatocyte-specific Bid deletion induces the formation of marked acute inflammatory foci and protects from both hepatocyte and sinusoidal endothelial cell death. (A) Haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections of Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice. Low magnification is emphasizing a number of inflammatory focal areas primarily consisting of infiltrated neutrophils. (B) Serial immunohistochemical staining specific for CD31 (endothelial cells), MPO (neutrophils), and TUNEL in control Bidfl/fl mice and vehicle control or Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Supplement Figure 3. Time-course study: hBid−/− mice show an increased trend for accumulation of eosinophils and no apparent differences in the quantity of total T-lymphocytes and mature macrophages over the period of 2 weeks post Jo2-injection. (A) Flow cytometry histograms of infiltrated eosinophils (ICAM+) at 3 h, 12 h, or 2 wk post Jo2-injection. Red line: hBid−/− Jo2 injection, Black line: hBid−/− saline injection. Bar graph shows quantification of infiltrated cells as shown by fold change compared to control saline injections at each time point. (B) Immunohistochemical staining specific for T-lymphocytes (CD3+) and mouse mature macrophages (F4/80+) in vehicle control and Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice at 3 h, 12 h, or 2 wk post injection.

Supplement Figure 4. In vitro and in vivo dose response experiments in WT hepatocytes and mice. These studies have been performed in order to determine best in vitro and in vivo concentrations of Jo2 for the main study. (A) Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assessment in the media and (B) inflammatory chemokine and cytokine gene expression in WT hepatocytes exposed to different concentrations of Jo2. (C) Liver macro pictures and haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections and (D) whole liver inflammatory chemokine and cytokine gene expression in WT mice exposed to different concentrations of Jo2. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to controls. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Supplement Figure 5. In vitro time-course study: hBid−/− hepatocytes have increased NF-kB activation over the period of 12 h post Jo2-treatment. Protein abundance of phosphorylated NF-κB is significantly increased in the whole lysates of hBid−/− as compared to WT hepatocytes at 1, 3 and 12 h post Jo2-treatment. WT hepatocytes show a modest increase in pNF-κB abundance at 1 and 3 h post Jo2-treatment as compared to untreated controls.

Supplement Figure 6. A schematic: Fas signaling induces differential activation of alternative inflammatory IL-1β, TNFα, and NF-κB pathways amplified in the absence of apoptotic Bid-mitochondrial loop. The low-dose Jo2 studies in WT and hBid−/− primary hepatocyte culture demonstrate that common neutrophilic chemokines, MIP-2 and KC, and cytokine IL-6, significantly increased their expression level in parallel to the amount of apoptosis in primary WT hepatocytes, while IL-1β and TNFα levels were significantly increased in hBid−/− compared to WT primary hepatocytes, thus being amplified in the absence of caspase-3 activation. In addition, the low-dose in vivo study demonstrated that there is an increase in the noncanonical IL-1β maturation 3 h post Jo2-injection and higher abundance of phosphorylated, active NF-κB with the sustained activation and presence in both nuclear and cytosolic fraction of the cells through a 12 h time-course in hBid−/− compared to WT mice. In summary, these data suggest that Fas signaling induces differential activation of alternative inflammatory IL-1β, TNFα, and NF-κB pathways amplified in the absence of apoptotic Bid-mitochondrial loop, dependent on capase-8 activation, but independent RIP-1/3 activity.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by NIH grants DK076852 and DK082451 to AEF.

We thank the UCSD Neuroscience Core and Jennifer Santini for microscopy assistance and their grant NS047101. We also thank Dr. Nissi Varki for the assistance with interpreting pathology slides and Dr. Ann Lin for assistance with apoptotic assays and image analysis.

Abbreviations used in this manuscript

- hBid−/−

hepatocyte-specific Bid knockout

- cKO

conditional knockout

- Bidfl/fl

albumin-cre negative Bid flox/flox control

- WT

wild-type

- TUNEL

terminal desoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick and labeling

- MIP

macrophage inflammatory protein

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- RIP

receptor-interacting protein

- IL

interleukin

- IFN

interferon

- IP

intraperitoneal

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Galle PR, Hofmann WJ, Walczak H, Schaller H, Otto G, Stremmel W, et al. Involvement of the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) receptor and ligand in liver damage. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1223–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suda T, Takahashi T, Golstein P, Nagata S. Molecular cloning and expression of the Fas ligand, a novel member of the tumor necrosis factor family. Cell. 1993;75:1169–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90326-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogasawara J, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Adachi M, Matsuzawa A, Kasugai T, Kitamura Y, et al. Lethal effect of the anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nature. 1993;364:806–9. doi: 10.1038/364806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itoh N, Yonehara S, Ishii A, Yonehara M, Mizushima S, Sameshima M, et al. The polypeptide encoded by the cDNA for human cell surface antigen Fas can mediate apoptosis. Cell. 1991;66:233–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 1997;88:355–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang K, Yin XM, Chao DT, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. BID: a novel BH3 domain-only death agonist. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2859–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacronique V, Mignon A, Fabre M, Viollet B, Rouquet N, Molina T, et al. Bcl-2 protects from lethal hepatic apoptosis induced by an anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nat Med. 1996;2:80–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janin A, Deschaumes C, Daneshpouy M, Estaquier J, Micic-Polianski J, Rajagopalan-Levasseur P, et al. CD95 engagement induces disseminated endothelial cell apoptosis in vivo: immunopathologic implications. Blood. 2002;99:2940–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faouzi S, Burckhardt BE, Hanson JC, Campe CB, Schrum LW, Rippe RA, et al. Anti-Fas induces hepatic chemokines and promotes inflammation by an NF-kappa B-independent, caspase-3-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:49077–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldstein AE, Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Higuchi H, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Diet associated hepatic steatosis sensitizes to Fas mediated liver injury in mice. J Hepatol. 2003;39:978–83. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldstein AE, Canbay A, Angulo P, Taniai M, Burgart LJ, Lindor KD, et al. Hepatocyte apoptosis and fas expression are prominent features of human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:437–43. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00907-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou C, Ma J, Wang X, Guo L, Zhu Z, Stoops J, et al. Lack of Fas antagonism by Met in human fatty liver disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:1078–85. doi: 10.1038/nm1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin XM, Wang K, Gross A, Zhao Y, Zinkel S, Klocke B, et al. Bid-deficient mice are resistant to Fas-induced hepatocellular apoptosis. Nature. 1999;400:886–91. doi: 10.1038/23730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croker BA, O’Donnell JA, Nowell CJ, Metcalf D, Dewson G, Campbell KJ, et al. Fas-mediated neutrophil apoptosis is accelerated by Bid, Bak, and Bax and inhibited by Bcl-2 and Mcl-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13135–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110358108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodama Y, Taura K, Miura K, Schnabl B, Osawa Y, Brenner DA. Antiapoptotic Effect of c-Jun N-terminal Kinase-1 through Mcl-1 Stabilization in TNF-Induced Hepatocyte Apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1423–34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liedtke C, Bangen JM, Freimuth J, Beraza N, Lambertz D, Cubero FJ, et al. Loss of caspase-8 protects mice against inflammation-related hepatocarcinogenesis but induces non-apoptotic liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2176–87. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramaiah SK, Jaeschke H. Hepatic neutrophil infiltration in the pathogenesis of alcohol-induced liver injury. Toxicol Mech Meth. 2007;17:431–40. doi: 10.1080/00952990701407702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, McQuade T, Siemer AB, Napetschnig J, Moriwaki K, Hsiao YS, et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell. 2012;150:339–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cullen SP, Henry CM, Kearney CJ, Logue SE, Feoktistova M, Tynan GA, et al. Fas/CD95-induced chemokines can serve as “find-me” signals fo apoptotic cells. Moll Cell. 2013;49:1034–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dosreis GA, Borges VM, Zin WA. The central role of Fas-ligand cell signaling in inflammatory lung diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:285–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strasser A, Jost PJ, Nagata S. The many roles of FAS receptor signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2009;30:180–92. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liedtke C, Trautwein C. The role of TNF and Fas dependent signaling in animal models of inflammatory liver injury and liver cancer. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:582–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang M, Ling Y, Yang CY, Liu H, Wang R, Wu X, et al. A novel Bcl-2 small molecule inhibitor 4-(3-methoxy-phenylsulfannyl)-7-nitro-benzofurazan-3-oxide (MNB)-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:471–81. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bossaller L, Chiang PI, Schmidt-Lauber C, Ganesan S, Kaiser WJ, Rathinam VA, et al. Cutting edge: FAS (CD95) mediates noncanonical IL-1beta and IL-18 maturation via caspase-8 in an RIP3-independent manner. J Immunol. 2012;189:5508–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan MJ, Kim Y, Liu Z. Membrane-bound Fas ligand requires RIP1 for efficient activation of caspase-8 within DISC. J Immunol. 2009;183(5):3278–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufmann T, Tai L, Ekert PG, Huang DC, Norris F, Lindemann RK, Johnstone RW, et al. The BH3-only protein bid is dispensable for DNA damage- and replicative stress-induced apoptosis or cell-cycle arrest. Cell. 2007;129:423–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schungel S, Buitrago-Molina LE, Nalapareddy P, Lebofsky M, Manns MP, Jaeschke H, et al. The strength of the Fas ligand signal determines whether hepatocytes act as type 1 or type 2 cells in murine livers. Hepatology. 2009;50:1558–66. doi: 10.1002/hep.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hikita H, Takehara T, Kodama T, Shimizu S, Shigekawa M, Hosui A, et al. Delayed-onset caspase-dependent massive hepatocyte apoptosis upon Fas activation in Bak/Bax-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2011;54:240–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.24305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boldin MP, Goncharov TM, Goltsev YV, Wallach D. Involvement of MACH, a novel MORT1/FADD-interacting protease, in Fas/APO-1- and TNF receptor-induced cell death. Cell. 1996;85:803–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muzio M, Chinnaiyan AM, Kischkel FC, O’Rourke K, Shevchenko A, Ni J, et al. FLICE, a novel FADD-homologous ICE/CED-3-like protease, is recruited to the CD95 (Fas/APO-1) death--inducing signaling complex. Cell. 1996;85:817–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo X, Budihardjo I, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Bid, a Bcl2 interacting protein, mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors. Cell. 1998;94:481–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross A, Yin XM, Wang K, Wei MC, Jockel J, Milliman C, et al. Caspase cleaved BID targets mitochondria and is required for cytochrome c release, while BCL-XL prevents this release but not tumor necrosis factor-R1/Fas death. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1156–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tait SW, Green DR. Mitochondria and cell death: outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:621–32. doi: 10.1038/nrm2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsujimoto Y. Cell death regulation by the Bcl-2 protein family in the mitochondria. J Cell Physio. 2003;195:158–67. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement Figure 1. Creation of hBid−/− mice by gene targeting and the comparable sensitivity to anti-Fas antibody in albumin cre negative Bid flox/flox control mice. (A) Vector construct strategy. Diagram of the Bid genomic locus and the homologues recombinant. Indicated are the restriction enzyme sites (B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII). Arrowheads labeled a, b and c indicate the positions of primers used in screening genotypes by PCR. (B) Western blot demonstrating the absence of Bid protein in hBid−/− albumin cre positive mice specifically in liver, but not in other organs. There were no changes in the abundance of other pro- or anti-apoptotic proteins belonging to the Bcl-2 family (Bcl-Xl, Bax and BAD). (C) Survival curve of WT mice (filled circles, n = 7) and albumin cre negative bid flox/flox mice (Bidfl/fl; triangles, n = 12) in response to a single IP injection of 100 μg anti-Fas antibody (Jo2) over the period of 12 hours post injection. Liver macro pictures and haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections of Jo2 injected WT and Bidfl/fl mice, respectively. Note the marked disruption of liver architecture, massive hepatic apoptosis and gross hemorrhage due to Fas activation in both WT and Bidfl/fl mice mice. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Supplement Figure 2. Hepatocyte-specific Bid deletion induces the formation of marked acute inflammatory foci and protects from both hepatocyte and sinusoidal endothelial cell death. (A) Haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections of Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice. Low magnification is emphasizing a number of inflammatory focal areas primarily consisting of infiltrated neutrophils. (B) Serial immunohistochemical staining specific for CD31 (endothelial cells), MPO (neutrophils), and TUNEL in control Bidfl/fl mice and vehicle control or Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Supplement Figure 3. Time-course study: hBid−/− mice show an increased trend for accumulation of eosinophils and no apparent differences in the quantity of total T-lymphocytes and mature macrophages over the period of 2 weeks post Jo2-injection. (A) Flow cytometry histograms of infiltrated eosinophils (ICAM+) at 3 h, 12 h, or 2 wk post Jo2-injection. Red line: hBid−/− Jo2 injection, Black line: hBid−/− saline injection. Bar graph shows quantification of infiltrated cells as shown by fold change compared to control saline injections at each time point. (B) Immunohistochemical staining specific for T-lymphocytes (CD3+) and mouse mature macrophages (F4/80+) in vehicle control and Jo2 injected hBid−/− mice at 3 h, 12 h, or 2 wk post injection.

Supplement Figure 4. In vitro and in vivo dose response experiments in WT hepatocytes and mice. These studies have been performed in order to determine best in vitro and in vivo concentrations of Jo2 for the main study. (A) Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assessment in the media and (B) inflammatory chemokine and cytokine gene expression in WT hepatocytes exposed to different concentrations of Jo2. (C) Liver macro pictures and haematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections and (D) whole liver inflammatory chemokine and cytokine gene expression in WT mice exposed to different concentrations of Jo2. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to controls. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Supplement Figure 5. In vitro time-course study: hBid−/− hepatocytes have increased NF-kB activation over the period of 12 h post Jo2-treatment. Protein abundance of phosphorylated NF-κB is significantly increased in the whole lysates of hBid−/− as compared to WT hepatocytes at 1, 3 and 12 h post Jo2-treatment. WT hepatocytes show a modest increase in pNF-κB abundance at 1 and 3 h post Jo2-treatment as compared to untreated controls.

Supplement Figure 6. A schematic: Fas signaling induces differential activation of alternative inflammatory IL-1β, TNFα, and NF-κB pathways amplified in the absence of apoptotic Bid-mitochondrial loop. The low-dose Jo2 studies in WT and hBid−/− primary hepatocyte culture demonstrate that common neutrophilic chemokines, MIP-2 and KC, and cytokine IL-6, significantly increased their expression level in parallel to the amount of apoptosis in primary WT hepatocytes, while IL-1β and TNFα levels were significantly increased in hBid−/− compared to WT primary hepatocytes, thus being amplified in the absence of caspase-3 activation. In addition, the low-dose in vivo study demonstrated that there is an increase in the noncanonical IL-1β maturation 3 h post Jo2-injection and higher abundance of phosphorylated, active NF-κB with the sustained activation and presence in both nuclear and cytosolic fraction of the cells through a 12 h time-course in hBid−/− compared to WT mice. In summary, these data suggest that Fas signaling induces differential activation of alternative inflammatory IL-1β, TNFα, and NF-κB pathways amplified in the absence of apoptotic Bid-mitochondrial loop, dependent on capase-8 activation, but independent RIP-1/3 activity.