Summary

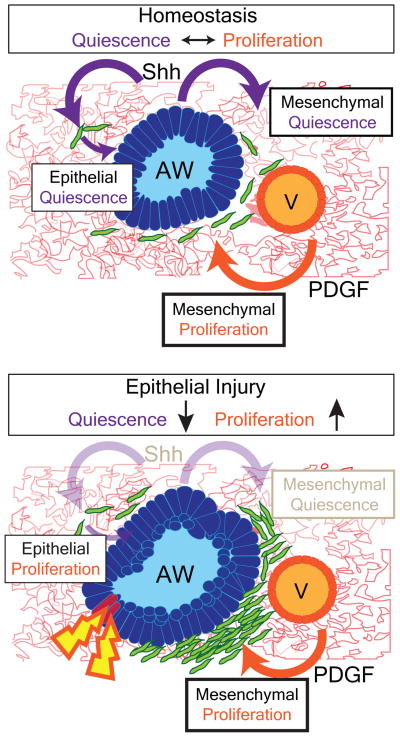

Postnatal tissue quiescence is thought to be a default state in the absence of a proliferative stimulus such as injury. Previous studies have demonstrated that certain embryonic development programs are reactivated aberrantly in adult organs to drive repair and regeneration1–3, it is not well understood how quiescence is maintained in organs such as the lung which displays a remarkably low level of cellular turnover4,5. We now demonstrate that quiescence in the adult lung is an actively maintained state and is regulated by hedgehog signaling. Epithelial-specific deletion of sonic hedgehog during postnatal homeostasis in the lung results in a proliferative expansion of the adjacent lung mesenchyme. Hedgehog signaling is initially down-regulated during the acute phase of epithelial injury as the mesenchyme proliferates in response, but returns to baseline during injury resolution as quiescence is restored. Activation of hedgehog during acute epithelial injury attenuates the proliferative expansion of the lung mesenchyme, whereas inactivation of hedgehog signaling prevents the restoration of quiescence during injury resolution. Finally, we show that hedgehog also regulates epithelial quiescence and regeneration in response to injury via a mesenchymal feedback mechanism. These results demonstrate that epithelial-mesenchymal interactions coordinated by hedgehog actively maintains postnatal tissue homeostasis, and deregulation of hedgehog during injury leads to aberrant repair and regeneration in the lung.

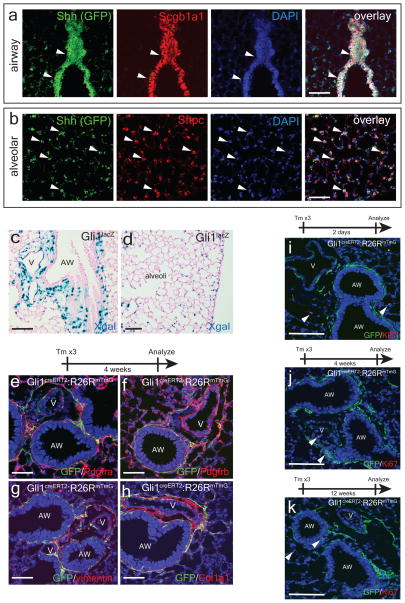

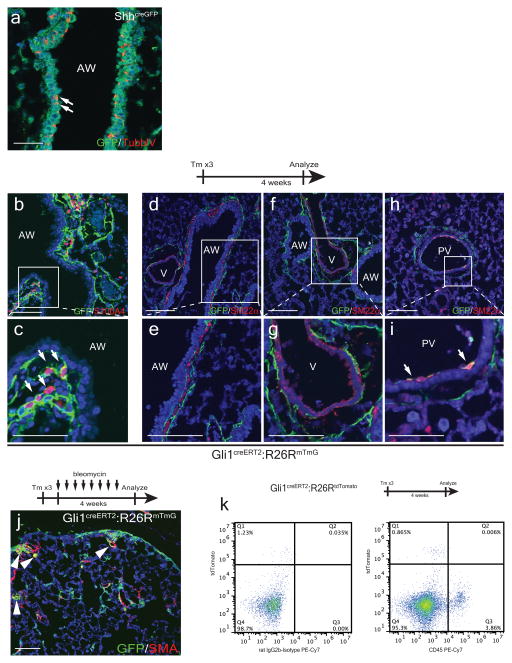

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway coordinates tissue-tissue interactions in multiple organs during embryonic development through paracrine activation of smoothened (Smo)-mediated downstream signaling events6,7. We have previously demonstrated that Shh expressed by nascent lung endoderm progenitors coordinates cardiopulmonary mesoderm progenitor differentiation into various cardiac and lung mesenchymal cell lineages8. To determine whether Hh signaling continues to be active in the postnatal adult lung, we utilized the ShhcreGFP reporter9 and our data show that Shh is expressed in the adult lung epithelium predominantly in the Scgb1a1+ club epithelial cells in the proximal airway (Fig. 1a), with scattered expression in ciliated epithelium (Extended Data Fig. 1a) and the Sftpc+ alveolar type II epithelial cells (Fig. 1b). The downstream transcriptional effector and target of hedgehog Gli110, is expressed predominantly in mesenchymal cells adjacent to the proximal airway and pulmonary artery (Fig. 1c), with scattered expression in the alveolar interstitium as previously reported (Fig. 1d)11. Lineage tracing in the adult lung with Gli1creERT2:R26RmTmG animals12, showed that Gli1+ Hh responsive cells express several mesenchymal markers including Pdgfrα, Pdgfrβ, vimentin, S100A4, and Col1a1 (Fig. 1e–h, ED Fig. 1b,c). Gli1+ Hh responsive mesenchymal cells do not contribute significantly to the smooth muscle lineage under homeostatic conditions, with the exception of rare venous smooth muscle within the proximal pulmonary venous myocardium (ED Fig. 1d–i) and myofibroblasts during fibrotic injury (ED Fig. 1j). Gli1+ cells do not contribute to cells of the hematopoietic lineage in the lung (ED Fig. 1k). Gli1+ cells remain quiescent up to 12 weeks after lineage labeling, with little to no significant expansion or Ki67 labeling (Fig. 1i–k).

Figure 1. The lung epithelium signals to the adjacent mesenchyme via paracrine Hh signaling during normal homeostasis.

The Shh ligand is expressed in airway epithelium marked by Scgb1a1 (a), with scattered expression in the Sftpc+ alveolar epithelium (b). The Gli1LacZ reporter is expressed in the mesenchyme adjacent to the airway and pulmonary artery (c) with scattered activation in the alveolar interstitium (d). Lineage traced Gli1+ cells express Pdgfrα+ and β+, vimentin, and Col1a1 (e–h). Lineage-traced Gli1+ cells do not expand in the adult lung after chase periods of 2 days-12 weeks, with negligible expression of the cell cycle marker Ki67 (i-k, arrowheads). AW= airway, V=blood vessel. Scale bars= 100 microns. Images representative of 3 animals with 5 sections examined per animal.

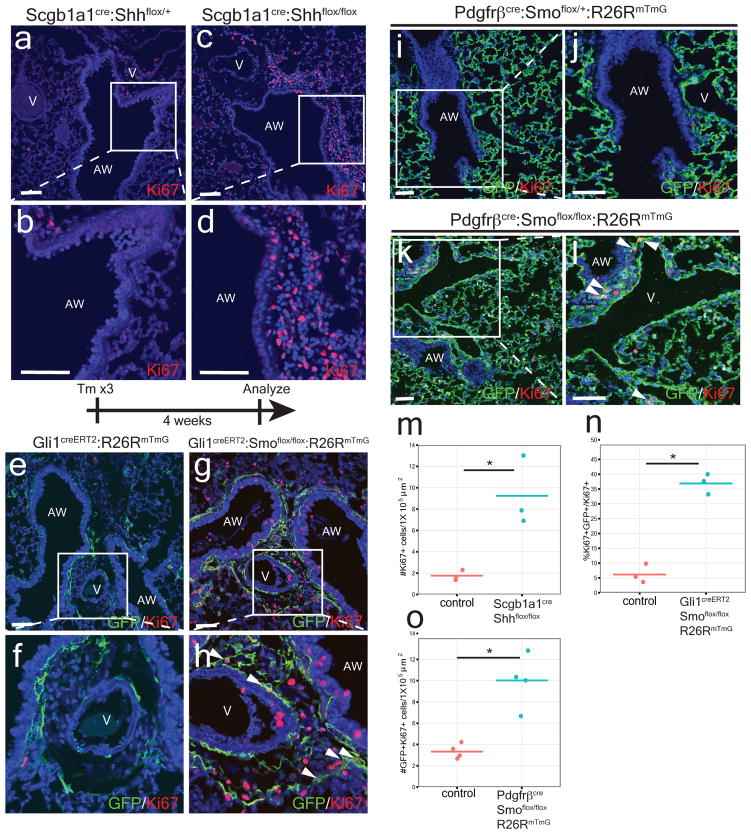

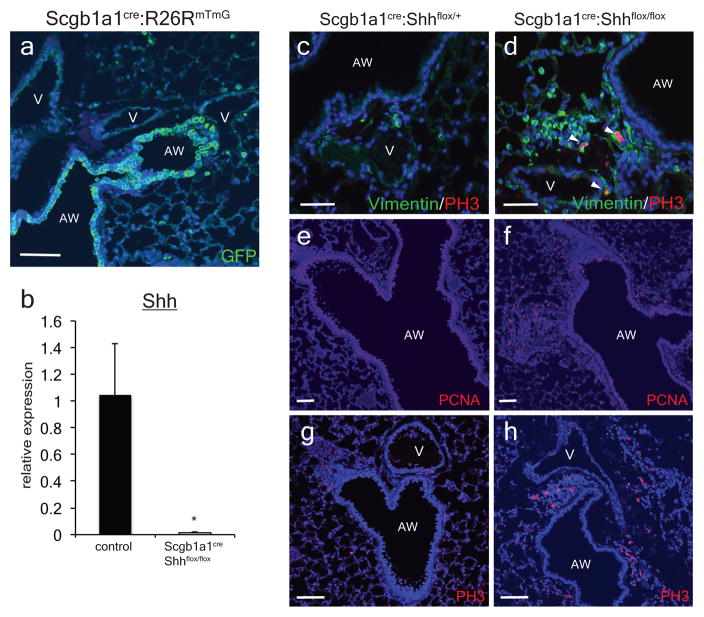

We deleted Shh using the Scgb1a1cre driver which is active in the airway epithelium to define the importance of Hh signaling in the postnatal lung (ED Fig. 2a–b)13. Examination of Scgb1a1cre:Shhflox/flox adult lungs reveals mesenchymal expansion and increased mesenchymal cell proliferation surrounding the airway epithelium (Fig. 2a–d,m and ED Fig. 2c–h). Thus, epithelial-specific loss of Shh in the postnatal lung is sufficient to induce cellular proliferation in the adjacent mesenchyme.

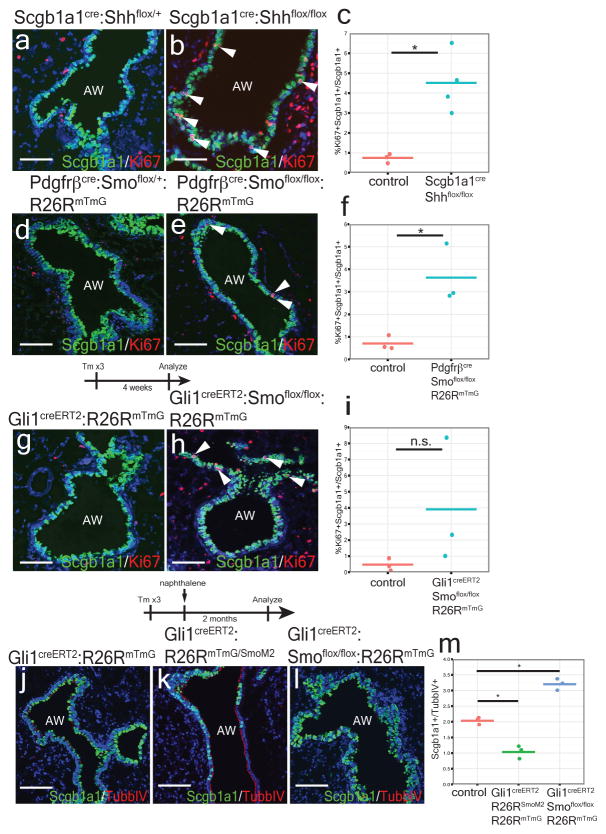

Figure 2. Postnatal activation of Hh signaling is required to maintain lung mesenchymal quiescence.

Deletion of Shh from airway epithelium increases proliferation in the mesenchyme surrounding the airway (a–d, m). Deletion of Smo within Gli1+ cells causes proliferation and mesenchymal expansion as noted by increased Ki67 expression (e–h, n). Deletion of Smo within Pdgfrβ+ mesenchyme shows increased mesenchymal proliferation in the adult lung (i–l,o). AW= airway, V=blood vessel, CKO=conditional knockout, blue represents DAPI counterstaining, Scale bars= 100 microns, * p<0.05. Data represent n=3 animals per group with 5 sections analyzed per animal. In vitro lung mesenchyme studies represent technical triplicates, with BrdU assay representative of three separate experiments. One sided t-test used to determine statistical significance with center value representing the mean and error bar representing s.d..

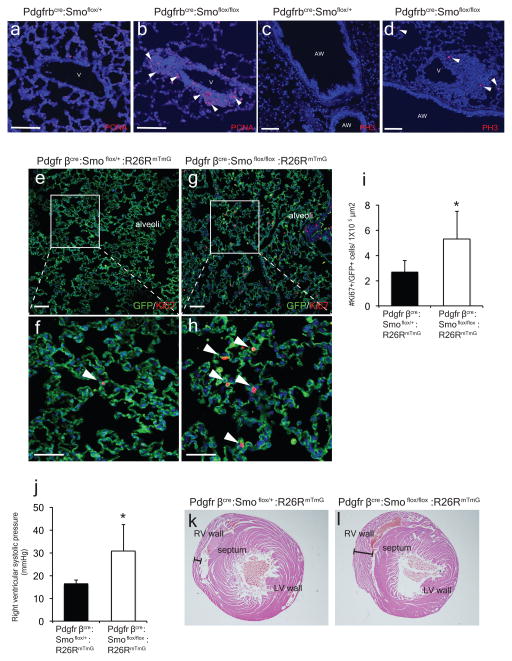

To address the cell-autonomous role of Hh signaling in adult lung mesenchyme, we deleted Smo within Gli1+ Hh responsive cells in the adult lung and followed their proliferative response. Four weeks after Smo deletion, lineage traced Gli1+ mesenchymal cells expanded relative to controls and exhibited increased cell proliferation (Fig. 2e–h,n). We also deleted Smo using the mesenchyme-specific Pdgfrβcre driver14, and PdgfβCre:Smoflox/flox:R26RmTmG adult mutants exhibit increased cell proliferation and expansion of the Pdgfrβ-derived population surrounding the airways and in the alveolar interstitium (Fig. 2i–l, o and ED Fig. 3a–i). Adult Pdgfrβcre:Smoflox/flox:R26RmTmG mutants older than 6 months exhibit elevated pulmonary arterial pressures, indicating that loss of Hh signaling at the bronchovascular interface causes pulmonary hypertension (ED Fig 3j–l).

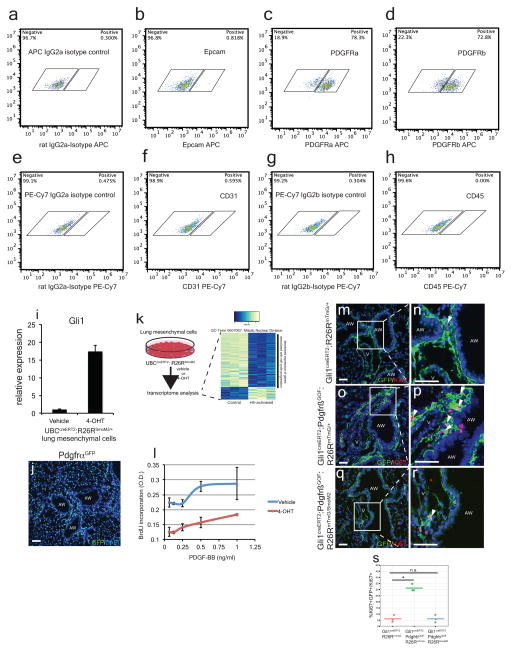

We then assessed the transcriptome of isolated adult lung mesenchymal cells expressing the activated SmoM2 mutant form of smoothened resulting in increased Gli1 expression (ED Fig. 4a–i)15. Unbiased gene ontology (GO) analysis showed highest enrichment in the subset of genes involved in “mitotic nuclear division,” with most of these transcripts down-regulated in Hh-activated fibroblasts (ED Fig. 4j, ED Tables 1 and 2), suggesting that Hh activation attenuates cell cycle progression in the adult lung mesenchyme.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Pdgfr signaling promotes postnatal mesenchymal proliferation16,17, and Pdgfr isoforms are expressed in the adult lung mesenchyme (Fig. 1, ED Fig. 4c, d, j). Therefore, we assessed the interaction between Hh and Pdgf signaling utilizing a gain-of-function mutant of Pdgfrβ (Pdgfrβ(S)K, hereafter referred to as PdgfrβGOF)17. Activation of Pdgfrβ within Hh responsive Gli1+ lung mesenchymal cells results in their proliferative expansion (ED Fig. 4m–p, s). However, concurrent expression of SmoM2 attenuates the Pdgfrβ-induced expansion of Gli1+ Hh responsive mesenchyme (Fig. 2q–r, s). Activation of Hh signaling in isolated lung mesenchymal cells in vitro (derived from UBCcreERT2:R26RSmoM2 animals) attenuates the proliferation induced by exogenous Pdgf-BB (ED Fig. 4l).

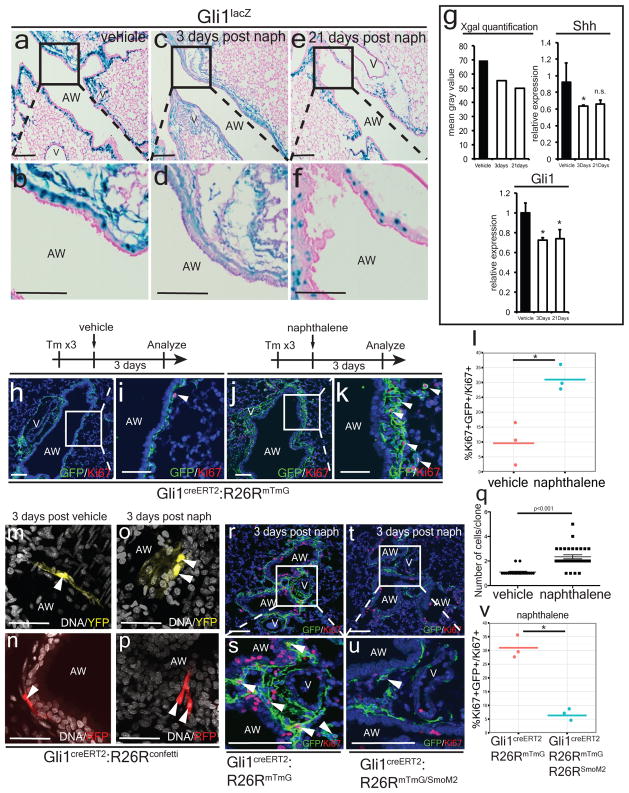

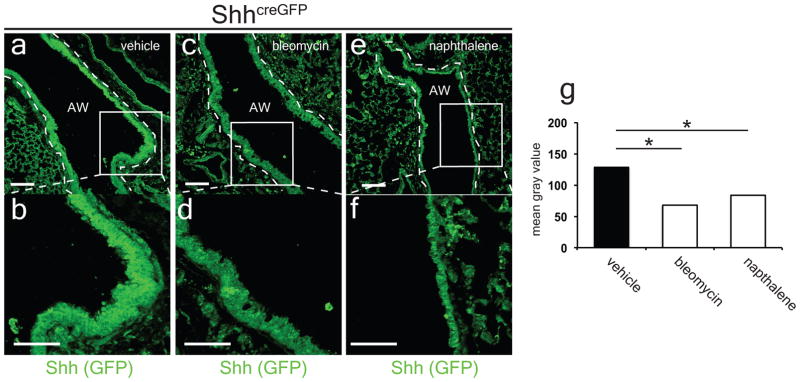

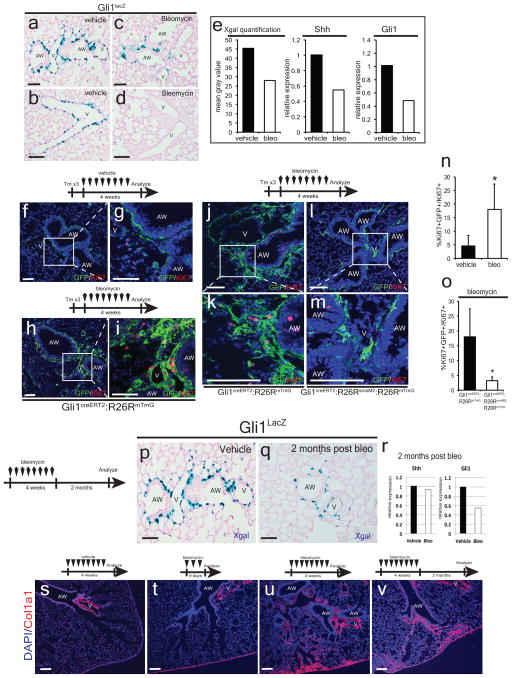

Next, we assessed the expression of Hh signaling components during airway epithelial injury with naphthalene18. Acute naphthalene injury caused a reduction in Hh activation as assessed by decreased Gli1LacZ reporter activity in the mesenchyme surrounding the airway, reduced expression of Shh and Gli1 transcripts, and decreased expression of GFP in the ShhcreGFP reporter (Fig. 3a–g, ED Fig. 5). Chronic repetitive bleomycin caused a similar reduction in Hh activation following injury (ED Figs. 5 and 6). Thus, Hh signaling is down-regulated in response to epithelial injury in the lung, and is not up-regulated as has been previously reported19,20. Of note, these results correlate with the loss of Shh expressing epithelium after injury.

Figure 3. Hh signaling modulates the acute mesenchymal response to epithelial injury.

Naphthalene injury down-regulates Gli1lacZ expression (a–f, n=2 animals per group) and Shh and Gli1 expression noted by Q-PCR (g, n=3 animals per group). Gli1+ lung cells undergo proliferative expansion shortly after naphthalene injury as measured by Ki67+ expression (h–l). Clonal analysis of Gli1+ lung cells at single cell resolution demonstrates clonal expansion three days after injury (m–q). Conditional activation of Smo (SmoM2) within lineage traced Gli1+ lung cells attenuates the proliferative expansion that follows epithelial injury with naphthalene (r–v). AW= airway, V=blood vessel, Scale bars= 100 microns, * p<0.05. Blue staining represents DAPI (H-K, Q-T) except in confetti experiments where white represent TO-PRO-3 DNA counterstaining. Data represent n=3 animals per group with 5 sections analyzed per animal. Clonal analysis represent >50 clones analyzed in 4 animals.

To assess the behavior of Gli1+ lung cells after epithelial injury, we exposed Gli1creERT2:R26RmTmG adult animals to tamoxifen followed by a one week washout period before inducing lung epithelial injury with naphthalene. Hh-activated Gli1+ lung cells rapidly undergo proliferative expansion after naphthalene injury (Fig. 3h–l). Similar experiments using the Gli1creERT2:R26Rconfetti mice demonstrate that individual Gli1+ cells clonally expand after naphthalene injury (Fig. 3m–q). Reconstitution of Hh activation with SmoM2 during acute epithelial injury attenuates the normal expansion of mesenchyme following injury (Fig. 3r–v). In the bleomycin injury model, Hh signaling is also down-regulated with Gli1+ mesenchymal cells after injury, which is similarly attenuated by the expression of activated SmoM2 (ED Fig. 6).

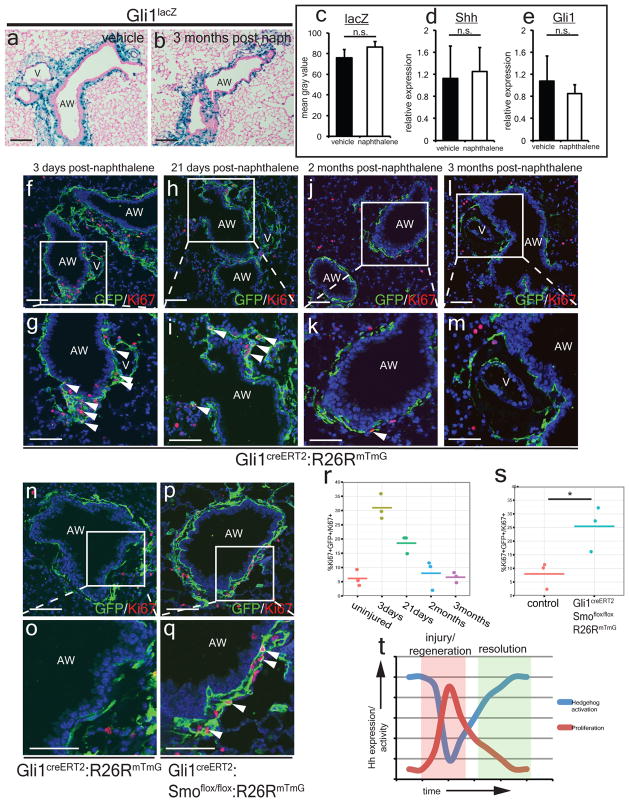

Despite an initial reduction in Hh activation during naphthalene injury, Shh and Gli1 expression return to homeostatic levels three months following injury (Fig 4a–e) as the Shh-expressing bronchial epithelium is reconstituted (ED Fig. 7a–d). Mesenchymal quiescence is also gradually restored after 2–3 months (Fig. 4f–m, r). Deletion of Smo within Gli1+ Hh responsive cells prevented the restoration of mesenchymal quiescence as these Gli1+ mesenchymal cells surrounding the airways continue to proliferate 2 months after naphthalene injury (Fig. 4n–q,s). These data show that Hh activation is dynamically regulated after epithelial injury and is inversely correlated with mesenchymal proliferation as injury repair and regeneration progresses (Fig. 4t).

Figure 4. Hh signaling modulates restoration of quiescence during injury resolution in the lung.

Hh activation returns to homeostatic levels three months after naphthalene injury in Gli1lacZ lungs (a–c, n=3 animals per group, 5 sections analyzed per animal) and Shh and Gli1 expression returns to normal as noted by Q-PCR (d,e, n=3 animals per group). Gli1+ lung cells undergo proliferative expansion shortly after naphthalene injury but return to quiescence by 2–3 months after injury (f–m, r). Conditional deletion of Smo in lineage traced Gli1+ lung cells prevents the restoration of mesenchymal quiescence (n–q, s). Relationship between Hh expression and activation and lung mesenchymal proliferation as plotted over time during injury and resolution (t). AW= airway, V=blood vessel, Scale bars= 100 microns, * p<0.05. Data represent n=3 animals per group with 5 sections analyzed per animal unless otherwise noted.

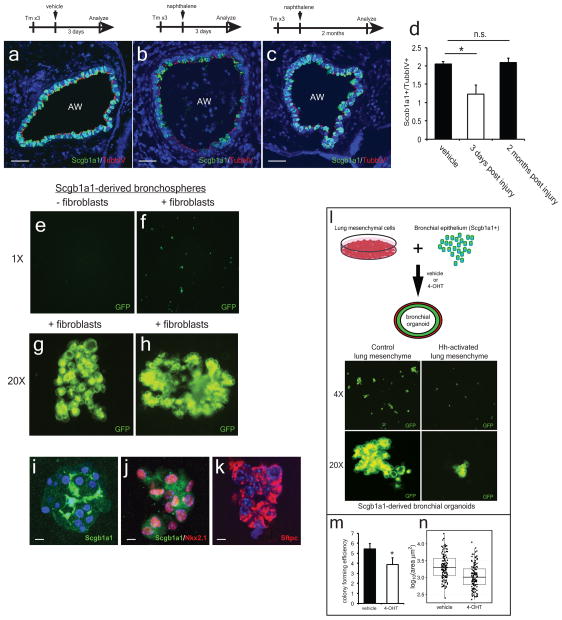

Bronchial Scgb1a1+ secretory cells have tremendous proliferative capacity to regenerate damaged epithelial airways after injury21,22 (ED Fig. 7a–d). Therefore, we assessed whether Hh activation in the mesenchyme alters secretory epithelial proliferation and regeneration in conditional Hh loss and gain of function mutants. Scgb1a1cre:Shhflox/flox and Pdgfrβcre:Smoflox/flox:R26RmTmG mutants demonstrate a significant increase in bronchial epithelial proliferation (Fig. 6a–f), while the Gli1creERT2:Smoflox/flox:R26RmTmG mutants show a trend towards increased epithelial proliferation during normal homeostasis (Fig. 6g–i). To determine whether mesenchymal activation of Hh signaling affects epithelial proliferation and regeneration after injury, we activated and deleted Smo within Gli1+ mesenchyme during naphthalene induced epithelial injury. Activation of Hh results in a dramatic loss of Scgb1a1+ secretory epithelium two months after naphthalene injury relative to multi-ciliated epithelium (TubbIV+) (Fig. 6k,m), which does not undergo cellular turnover with naphthalene injury23. In contrast, inactivation of Hh signaling promotes excessive Scgb1a1+ club cell regeneration leading to bronchial hyperplasia (Fig. 6l,m). Next, we generated lung organoids from Scgb1a1-derived epithelium cultured it in the presence or absence of isolated lung mesenchyme (ED Fig. 7e–n). These organoids predominantly formed colonies expressing markers of the secretory lineage with a small fraction generating alveolar epithelial cells, while those without mesenchyme failed to form colonies (ED Fig. 7e–k). Activation of SmoM2 in the co-cultured lung mesenchyme reduced the number and size of the epithelial colonies (ED Fig. 7l–n). These data show that Hh promotes epithelial quiescence via a mesenchymal feedback mechanism, possibly by down-regulating stromal factors necessary for epithelial proliferation.

In this study, we have demonstrated that the lung epithelium actively maintains mesenchymal quiescence through paracrine Hh signaling, which also regulates a feedback loop to maintain epithelial quiescence. This finding stands in contrast to the known role of Shh in promoting cell proliferation during tissue development as well as its role in promoting tumorgenesis in adults. While previous reports have suggested that Hh signaling is pro-mitogenic in the adult lung11,19,20, our study is the first report to utilize multiple genetic models to assess Hh function in the adult lung in vivo and in vitro. Our data indicates that certain signaling pathways such as Hh maintain a balance between proliferation and quiescence during lung homeostasis and regeneration. Our studies reveal that disruption of this balance upon injury can lead to changes in expansion of the mesenchyme, which may disrupt epithelial regeneration after injury or in disease (ED Fig. 8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Generation and genotyping of the ShhcreGFP 9, Gli1LacZ 10 Gli1creERT212, Scgb1a1cre13, Pdgfrβcre14, R26Rconfetti24, Smoflox/flox25, Shhflox/flox26, R26RmTmG27, R26RSmoM215, Pdgfrβ(S)K 17, UBCCreERT2 28 lines have been previously described. The animals were housed and treated in accordance with the IACUC protocol approved at the University of Pennsylvania. Animals between the ages of 8–12 weeks old were used for the experiments with balance of gender between groups. Tamoxifen (Sigma) was dissolved in corn oil and administered intraperitoneally at 200mg/kg per day × 3 days for lineage tracing studies, with the exception of clonal analysis studies with the R26Rconfetti reporter, where only one dose of tamoxifen was given at 200mg/kg.

Histological analysis

Mouse lungs were inflated and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in a series of increasing ethanol concentration washes, embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Antibodies used were anti-sm22α (goat anti-SM22α 1:200 Abcam), GFP (goat anti-GFP 1:100 Abcam, rabbit anti-GFP 1:100 Molecular Probe), Scgb1a1 (goat anti-Scgb1a1 1:20 Santa Cruz), SPC (rabbit-anti SPC 1:500 Chemicon), Pdgfrα (rabbit anti-Pdgfrα 1:50 Cell Signaling), Pdgfrβ (rabbit anti-Pdgfrβ 1:100 Cell Signaling), vimentin (rabbit anti-vimentin 1:100 Santa Crux), collagen type1 (rabbit anti-Col1 1:500 Abcam), Ki67 (rabbit anti-Ki67 1:50 Abcam), PCNA (mouse anti-PCNA 1:50 Biocare), PO4-Histone H3 (mouse anti-PO4-Histone H3 1:200 Cell Signaling), TubbIV (mouse anti-TubbIV 1:20 Biogenex), S100A4 (rabbit anti-S100A4 1:200 Abcam). LacZ staining of lungs was performed as previously described8. The slide was imaged on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope and analyzed in ImageJ software.

Animal injury experiments

For acute naphthalene injury, mice were given 300mg/kg of naphthalene (Sigma) dissolved in corn oil via intraperitoneal injection. For chronic bleomycin injury, mice were given 50 U/kg of pharmaceutical grade bleomycin (Hospira) dissolved in PBS via intraperitoneal injection twice a week for four weeks.

Measurement of pulmonary artery pressure

Following anesthetization with Avertin, the trachea was cannulated, and mice were ventilated using a MiniVent Type 845 (Harvard Apparatus). The chest cavity was opened to expose the heart, and a Micro-Tip Catheter Transducer SPR-1000 (Millar Instruments) was inserted into the RV. Systolic right ventricle pressure was measured as a surrogate for systolic pulmonary artery pressure, recorded on a PowerLab 4/30 instrument (ADInstruments), and analyzed using Chart 5 Pro software (ADInstruments). Pressure measurements associated with heart rates outside the range of 300–500 bpm were excluded from analysis. For each mouse, 2–4 measurements were analyzed, each corresponding to the average of 10–20 individual data points. Operator was blinded to the mouse genotype and three mice of genotype were examined.

Clonal analysis of Gli1creERT2:R26Rconfetti lungs

For clonal analysis of Gli1creERT2:R26Rconfetti mice, lungs were inflated and fixed in 2% PFA overnight, washed with cold PBS four times, and then cleared using the Scale reagent as reported29. Clarified lung specimen was then counterstained with TO-PRO3 (Life Technologies) for nuclear counterstaining and dissected into slices ~1mm thick and mounted on a Fastwell with coverslip and sealed. Sections were imaged on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope and analyzed in ImageJ software. Thick sections were randomly sampled for single-colored clones with identical-color labeled cells within 50 microns of each other considered as derived from the same clone. Color and spatially-segregated clones of 1–5 cells were identified and plotted in a box plot according to experimental conditions (vehicle vs. naphthalene).

Cell counting and image analysis

Sections included in cell count analysis were acquired using confocal microscopy. At least four animals per genotype were used. Cell counts were performed on ImageJ using the “Cell Counter” plug-in and performer was blinded to the specimen genotype and condition. Results were averaged between each specimen and standard deviations were calculated per genotype. 1-tailed paired t-tests were used to determine the p value. Quantification of X-gal positive or GFP+ pixels in lung sections was performed using ImageJ. Lung sections were captured on a Nikon Eclipse light microscope under identical exposures and converted to monochrome 8-bit images, inverted, and the mean gray value was quantified over the X-gal or GFP positive area surrounding the airway and vasculature.

Q-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from whole lung or cultured primary lung fibroblasts using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and following the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the SuperScript Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen).

Quantitative PCR was performed using the SYBR Green system (Applied Biosystems) with the following primers: Shh F′ 5′-AAGTACGGCATGCTGGCTCGC-3′ Shh R′ 5′-QCCACGGAGTTCTCTGCTTTCACAG-3′ Gli1 F′ 5′-GTGCACGTTTGAAGGCTGTC-3′ Gli1 R′ 5′-TAAAGGCCTTGCTGCAACCT-3′ GAPDH F′ 5′-CCCCAGCAAGGACACTGAGCAAGAG-3′ GAPDH R′ 5′-GGCCCCTCCTGTTATTATGGGGGGT-3′ GAPDH expression values were used to control for RNA quantity. Data are shown as the average of a minimum of three biological replicates for each genotype/condition ± SD.

Isolation and culture of lung mesenchymal cells

Whole lung is dissected from C57BL6 male adult animal and tracheally perfused with a digestion cocktail of Collagenase Type I (450U/ml, Gibco), elastase (4U/ml, Worthington) and Dispase (1:10 BD Bioscience) and removed from the chest. The lung is further diced with razor blades and the mixture is incubated at 37 degrees Celsius for 25 minutes and vortexed intermittently. The mixture is then washed with DMEM-F12 and incubated with 0.1%Trypsin-EDTA for 20 minutes and vortexed intermittently. The mixture is passed through a 100 micron cell strainer and resuspended in RBC lysis buffer, before passing through a 40 micron cell strainer. The resuspended cells are cultured on gelatin-treated tissue culture plates with DMEM-F12 plus 10% fetal calf serum. Media is refreshed every other day and primary lung mesenchymal cells are maintained for no more than three passages.

Microarray

Primary lung mesenchymal cells were isolated from UBCcreERT2:R26RSmoM2 adult mice and grown in DMEM-F12 plus 10% fetal calf serum. The cells were treated with vehicle or 1μg/ml of 4-OH-tamoxifen in DMEM F12 without serum and total RNA was isolated after 48 hours. Biotinylated cRNA probe libraries were generated from these RNA samples and assayed with the Affymetrix Mouse Gene 2.0ST genechip. Microarray data were analyzed using the Oligo package available at the Bioconductor Web site (http://www.bioconductor.org). The raw data were background-corrected by the robust multichip average (RMA) method and then normalized by an invariant set method. Genes with 80% of samples with an expression signal above the negative control probes were considered detectable or present. Differential gene expression analysis between control and mutant mice was analyzed by the Limma package available at the Bioconductor Web site. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparison using a false discovery rate. GO enrichment analysis was performed using the Bioconductor package topGO. The Gene Expression Omnibus accession number for the microarray data produced in these studies is GSE68201.

Cell proliferation assay

Lung mesenchymal cells were isolated from UBCcreERT2:R26RSmoM2 animals and plated at 1×104 cells/well in 96 well plates and grown for 3 days with vehicle or 1ug/ml of 4-OH-tamoxifen until cells are confluent. Cells are then incubated in serum free DMEM F12 for 24 hours before Pdgf-BB (mouse, R&D) was added and cultured for another 24 hours. BrdU was then added to the media after 24 hours of Pdgf-BB incubation and BrdU incorporation was assayed after four hours according to manufacturer instructions (Cell Signaling Technology, BrdU cell proliferation assay kit).

Bronchial organoid formation assay

GFP+ bronchial epithelium were FACS sorted from Scgb1a1cre:R26RmTmG lungs and co-cultured with lung mesenchyme isolated from UBCcreERT2:R26RSmoM2 animals (5×103 epithelial cells:5×104 mesenchymal cells/well) in a modified MTEC media diluted 1:1 in growth factor reduced Matrigel (Corning). Modified MTEC culture media is comprised of small airway basal media (SABM) (Lonza) with selected components from SAGM bullet kit (Lonza) including insulin, transferrin, bovine pituitary extract, retinoic acid, and gentamicin/amphotericin B. Additional components include 25 ng/mL mEGF (Sigma), 0.1 ug/mL cholera toxin (Sigma), and 5% FBS (Life Technologies). Cell suspension-Matrigel mixture is placed in a transwell and incubated in growth media with 10 uM ROCK inhibitor (Sigma) in a 24 well plate with vehicle or 1ug/ml 4-OH-tamoxifen for 48 hours, after which the media was replenished every 48 hours (lacking tamoxifen). Colonies are assayed after 14 days. Each experimental condition is performed in quadruplicates and counted blinded to the experimental condition. Colony forming efficiency = (number of GFP+ colonies/number GFP+ epithelial cells cultured per well) × 100. Areas of individual colonies are assayed on ImageJ and over 140 colonies are randomly sized per experimental condition.

Extended Data

ED Figure 1. Characterization of Hh signaling in the lung.

A small number of TubbIV+ ciliated cells express GFP in the ShhcreGFP reporter (a,). Gli1+ Hh activated cells co-label with S100A4 (b and c), a fibroblast marker. Lineage tracing of Gli1+ Hh activated cells shows little to no co-localization of GFP+ cells with the airway smooth muscle (d,e) or the vascular smooth muscle of the adjacent pulmonary artery (f,g). The rare exception occurs in the pulmonary vein where Gli1+ Hh activated cells contribute to the venous smooth muscle that is surrounded by the venous myocardium of the proximal pulmonary vein (h,i). Gli1+ cells also generates myofibroblasts after fibrotic injury such as that induced by bleomycin (j). Lung Gli1+ cells do not contributes to cells of hematopoietic lineage as marked by CD45 (k). AW= airway, V=blood vessel, PV=pulmonary vein. Scale bars= 100 microns. Images representative of 3 animals with 5 sections examined per animal.

ED Figure 2. Conditional deletion of Shh from the adult airway epithelium increases proliferation in the adjacent mesenchyme.

The Scgb1a1cre driver predominantly marks the airway epithelium in the adult lung when crossed with the R26RmTmG reporter (a). Whole lung mRNA transcript analysis reveals efficient deletion of Shh transcripts in the Scgb1a1cre:Shhflox/flox animals compared to controls (Shhflox/flox) (b, n=4 animals). Deletion of Shh from the airway epithelium resulted in an increased expression of proliferative markers, PCNA and phospho-Histone H3 (PH3) in the mesenchyme surrounding the airways in Scgb1a1cre:Shhflox/flox mutants (d,f,h, n=4 animals) versus controls (Scgb1a1Cre:Shhflox/+) (c,e,g, n=3 animals). AW= airway, V=blood vessel. Scale bars= 100 microns. *p<0.05.

ED Figure 3. Conditional deletion of Smo from Pdgfrβ-derived mesenchyme increases mesenchymal proliferation at the epithelial-mesenchymal interface and vascular remodeling.

Deletion of Smo from Pdgfrβ-derived mesenchyme resulted in increased expression of proliferative markers, PCNA and PH3 in the mesenchyme at the epithelial-mesenchymal interface of Pdgfrβcre:Smoflox/flox mutants (b,d) versus controls (Pdgfrβ Cre:Smoflox/+)(a,c). Pdgfrβcre:Smoflox/flox:R26RmTmG/+ mutants exhibit increased Ki67+ cells within lineage traced GFP+ cells in the alveoli compared to controls (e–i, n=4 animals per group). Aged Pdgfrβcre:Smoflox/flox:R26RmTmG/+ mutants (>6 months old) spontaneously develop pulmonary hypertension with increased right ventricular systolic pressure (j, n=3 animals per group) and RV wall thickness (k,l). Scale bars= 100 microns. *p<0.05.

ED Figure 4. Characterization of isolated lung mesenchyme.

Isolated mesenchymal cells in vitro predominantly express Pdgfrα and β (c,d, compared to isotype control a), but not epithelial marker, Epcam (b, compared to isotype control a), nor endothelial marker, CD31 (f, compared to isotype control e), nor hematopoietic marker, CD45 (h, compared to isotype control g). Expression of the constitutively active form of Smo (SmoM2) by 4OH-tamoxifen induction significantly up-regulates Gli1 expression in the isolated lung mesenchyme after 48 hours (i). GFP staining of the PdgfrαGFP reporter demonstrates that Pdgfrα+ cells are expressed broadly in the lung (j). Activation of Smo in isolated lung mesenchymal cells leads to reduced expression of cell cycle progression genes (k). Hh activation of lung mesenchyme with SmoM2 attenuated the proliferation induced by Pdgf-BB ligand in vitro as assayed by BrdU incorporation (l). Expression of activated Pdgfrβ(PdgfrβGOF) within Gli1+ cells resulted in their proliferative expansion (m-p, s). Concurrent activation of SmoM2 attenuated the proliferative expansion induced by PdgfrβGOF (q–r, s, n=3 animals per group). Scale bars=100 microns.

ED Figure 5. Shh expression is decreased with bleomycin and naphthalene injury to the airway.

Repetitive bleomycin injury after one month or single-dose naphthalene injury after three days reduced GFP expression in the airways of the ShhcreGFP reporter compared to controls (a–g). Data represent n=2 animals per group with 5 sections analyzed per animal, AW= airway. Scale bars= 100 microns. *p<0.05.

ED Figure 6. Hedgehog modulates mesenchymal response to bleomycin injury.

Chronic repetitive injury to the lung epithelium with bleomycin over 4 weeks down-regulates Gli1 expression in the mesenchyme adjacent to the airways in Gli1lacZ lungs as noted by histochemical staining for β-galactosidase activity (a–d) and as noted using X-gal quantification and Q-PCR analysis of Shh and Gli1 expression after four weeks of repetitive injury (e, n=2 animals per group). Lineage-traced, Gli1+ Hh activated lung mesenchymal cells undergo proliferative expansion after repetitive bleomycin injury with an increase in Ki67+ mesenchymal cells (f–i,n, n=4 animals per group). Expression of SmoM2 within lineage traced Gli1+ lung mesenchymal cells attenuates the proliferative expansion that normally follows repetitive bleomycin injury (j–m,o, n=3 animals per group). Gli1 expression remain reduced 2 months after the end of bleomycin treatment (p–r, n=2 animals per group), which might be due to the persistent scarring that is observed after repetitive bleomycin injury (s–v). AW= airway, V=blood vessel, Scale bars= 100 microns, * p<0.05.

ED Figure 7. Airway epithelium is able to regenerate in vitro and in vivo.

Scgb1a1+ secretory epithelium is initially depleted 3 days following naphthalene injury while TubbIV+ ciliated epithelium remains relatively intact (a–b,d, n=3 animals per group). However, 2 months after the initial naphthalene injury, Scgb1a1+ secretory epithelium repopulates the airway and the ratio of secretory/ciliated cells is restored to levels prior to injury (c,d). GFP+ bronchial epithelial cells isolated from Scgb1a1cre:R26RmTmG animals were cultured in the presence or absence of isolated lung mesenchymal cells, and only those co-cultured with lung mesenchymal cells were able to form organoids (e–f). Examples of the 3-dimensional structures formed by the bronchial organoids in the presence of lung mesenchyme (g–h). Scgb1a1-derived organoids predominantly express markers of secretory airway differentiation, including Scgb1a1 and Nkx2.1 (i and j), while a minority expresses markers of alveolar epithelial lineage including Sftpc (k). Co-culture of lung mesenchyme and bronchial epithelium induces organoid formation (l), which is inhibited in number (m) and colony size (n) with activation of Hh in the mesenchyme. AW= airway. Scale bars= 100 microns. * p<0.05. n = 3 animals per group for injury time points. In vitro organoid studies represent technical quadruplicates, with >140 randomly selected clones analyzed for size per group.

ED 8. Hh signaling mediates both mesenchymal and epithelial quiescence during homeostasis and injury repair in the lung.

The lung epithelium actively maintains mesenchymal quiescence through paracrine Hh signaling, which also regulates a feedback loop to maintain epithelial quiescence. Epithelial injury leads to down-regulation of Hh signaling and loss of mesenchymal quiescence, which in turn stimulates epithelial regeneration to replete the airway epithelium until homeostasis is re-established.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5. Hh signaling regulates epithelial quiescence via mesenchymal feedback.

Deletion of Shh from the proximal secretory epithelium and deletion of Smo within cells derived from Pdgfrβ+ mesenchyme increase proliferation of Scgb1a1+ club cells during homeostasis (a–f). Inducible deletion of Smo within Gli1+ lung mesenchymal cells results in a non-significant trend towards increased Scgb1a1+ club cell proliferation (g–i). Activation of SmoM2 in Gli1+ mesenchyme results in impaired regeneration of Scgb1a1+ cells after naphthalene injury, whereas deletion of Smo in the mesenchyme induces excessive expansion of Scgb1a1+ cells resulting in bronchial hyperplasia (j–m). AW= airway., Scale bars= 100 microns, * p<0.05. Data represent n=3 animals per group with 5 sections analyzed per animal.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the input of Mark Kahn, Michael Beers, and Rupal Shah in these studies. The authors are grateful to Andrea Stout and the Department of Cell and Developmental Biology Microscopy Core for help in imaging. These studies were supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (HL110942, HL100405, HL087825 to E.E.M). T.P. is supported by the American Heart Association Fellow-to-Faculty Transition Award, Actelion ENTELLIGENCE Award, and K08-HL121146.

Footnotes

T.P. and E.E.M. designed the overall experimental strategy. T.P. and R.S.K. performed lineage tracing and animal injury experiments. T.P. and D.B.F. performed in vitro BrdU and organoid experiments. T.W. performed right heart catheterization on the animals. S.Z., L.C., and M.M.L. performed histology and immunohistochemistry. T.P., D.B.F., K.S.R. M.P.M. and E.E.M. analyzed the data. T.P. and E.E.M. wrote and edited the manuscript with input from all authors.

The Gene Expression Omnibus accession number for the microarray data produced in these studies is GSE68201.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Beers MF, Morrisey EE. The three R’s of lung health and disease: repair, remodeling, and regeneration. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:2065–2073. doi: 10.1172/JCI45961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herriges M, Morrisey EE. Lung development: orchestrating the generation and regeneration of a complex organ. Development. 2014;141:502–513. doi: 10.1242/dev.098186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogan BL, et al. Repair and Regeneration of the Respiratory System: Complexity, Plasticity, and Mechanisms of Lung Stem Cell Function. Cell stem cell. 2014;15:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blenkinsopp WK. Proliferation of respiratory tract epithelium in the rat. Experimental cell research. 1967;46:144–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(67)90416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breuer R, Zajicek G, Christensen TG, Lucey EC, Snider GL. Cell kinetics of normal adult hamster bronchial epithelium in the steady state. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 1990;2:51–58. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/2.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMahon AP, Ingham PW, Tabin CJ. Developmental roles and clinical significance of hedgehog signaling. Current topics in developmental biology. 2003;53:1–114. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(03)53002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lum L, Beachy PA. The Hedgehog response network: sensors, switches, and routers. Science. 2004;304:1755–1759. doi: 10.1126/science.1098020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng T, et al. Coordination of heart and lung co-development by a multipotent cardiopulmonary progenitor. Nature. 2013;500:589–592. doi: 10.1038/nature12358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harfe BD, et al. Evidence for an expansion-based temporal Shh gradient in specifying vertebrate digit identities. Cell. 2004;118:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai CB, Auerbach W, Lee JS, Stephen D, Joyner AL. Gli2, but not Gli1, is required for initial Shh signaling and ectopic activation of the Shh pathway. Development. 2002;129:4753–4761. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.20.4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, et al. Hedgehog signaling in neonatal and adult lung. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2013;48:703–710. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0347OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn S, Joyner AL. In vivo analysis of quiescent adult neural stem cells responding to Sonic hedgehog. Nature. 2005;437:894–897. doi: 10.1038/nature03994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, et al. Cre-mediated recombination in mouse Clara cells. Genesis. 2008;46:300–307. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foo SS, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls cell motility and adhesion during blood-vessel-wall assembly. Cell. 2006;124:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong J, Mao J, Tenzen T, Kottmann AH, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signaling in the neural crest cells regulates the patterning and growth of facial primordia. Genes & development. 2004;18:937–951. doi: 10.1101/gad.1190304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olson LE, Soriano P. Increased PDGFRalpha activation disrupts connective tissue development and drives systemic fibrosis. Developmental cell. 2009;16:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson LE, Soriano P. PDGFRbeta signaling regulates mural cell plasticity and inhibits fat development. Developmental cell. 2011;20:815–826. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckpitt AR, Bahnson LS, Franklin RB. Comparison of the arachidonic acid and NADPH-dependent microsomal metabolism of naphthalene and 2-methylnaphthalene and the effect of indomethacin on the bronchiolar necrosis. Biochemical pharmacology. 1986;35:645–650. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolanos AL, et al. Role of Sonic Hedgehog in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2012;303:L978–990. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00184.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watkins DN, et al. Hedgehog signalling within airway epithelial progenitors and in small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2003;422:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature01493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zemke AC, et al. beta-Catenin is not necessary for maintenance or repair of the bronchiolar epithelium. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2009;41:535–543. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0407OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, et al. Development and regeneration of Sox2+ endoderm progenitors are regulated by a Hdac1/2-Bmp4/Rb1 regulatory pathway. Developmental cell. 2013;24:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rawlins EL, Ostrowski LE, Randell SH, Hogan BL. Lung development and repair: contribution of the ciliated lineage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:410–417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610770104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snippert HJ, et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long F, Zhang XM, Karp S, Yang Y, McMahon AP. Genetic manipulation of hedgehog signaling in the endochondral skeleton reveals a direct role in the regulation of chondrocyte proliferation. Development. 2001;128:5099–5108. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis PM, et al. Cholesterol modification of sonic hedgehog is required for long-range signaling activity and effective modulation of signaling by Ptc1. Cell. 2001;105:599–612. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruzankina Y, et al. Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell stem cell. 2007;1:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hama H, et al. Scale: a chemical approach for fluorescence imaging and reconstruction of transparent mouse brain. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:1481–1488. doi: 10.1038/nn.2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.