Abstract

Background

Approximately 50 % of heart failure cases are due to diastolic failure. Generally, it is thought that asymptomatic diastolic dysfunction precedes the development of diastolic heart failure, representing an ideal time for intervention. Previous studies have examined progression rates in non-minority populations only.

Objective

To determine the rate of diastolic dysfunction progression and the associated risk factors in a predominately ethnic minority population.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study of participants drawn from the echocardiogram database and Electronic Health Record (EHR) for an academic medical center. Individuals with 2 or more echo-cardiograms showing diastolic dysfunction during a six-year study period (2006–2012) were selected.

Main Outcome Measures

Change in diastolic function grade over time and risk factors associated with this change.

Results

During the six-year retrospective study period, 154 patients with 2 or more echocardiograms demonstrating diastolic dysfunction were reviewed; these represented 496 echocardiograms. The mean time between echocardiograms was 1.9 years. Mean age was 64.6 (±10.1) years, 81 % were female, and average BMI was 30.5(±7.4). The majority of subjects had Grade I diastolic dysfunction at the initial examination (87.7 % (n = 135)); 9 % (n = 14) had Grade II, and 3 % (n = 5) had Grade III. Approximately 27.9 % (n = 43) of the study cohort demonstrated overall worsening grade of diastolic dysfunction over time. Diastolic dysfunction grade was unchanged in 62 % (n = 96), improved in 9.7 % (n = 14), and worsened then improved in 0.7 % (n = 1).

Conclusions

Our study showed a slightly higher rate of diastolic dysfunction progression in this predominately ethnic minority population. This is consistent with a previous study in a non-minority population demonstrating the progressive nature of diastolic dysfunction over time. Understanding the role of cardiovascular disease risk factors in accelerating progression rates from asymptomatic diastolic dysfunction to symptomatic stages is paramount to optimize intervention strategies.

Keywords: Diastolic dysfunction, Ethnic minorities, Progression

1 Introduction

Heart failure is a major public health challenge in the United States, representing one of the leading causes of hospital admissions [1, 2]. Among patients with the clinical syndrome of heart failure (HF), approximately half have preserved systolic function, also referred to as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) or diastolic heart failure [3]. The pathophysiology involving diastolic heart failure is complex and not fully delineated [4]; however diastolic heart failure has been associated with diabetes, smoking, and obesity [5]. In ethnic minorities, heart failure appears to have an earlier age onset [6]. In the United States, African Americans have the highest prevalence of heart failure than persons of other races, present with heart failure at younger ages, and are less likely to have coronary artery disease as the primary etiology [6]. Similarly Hispanics and South Asians also demonstrate earlier age onset of heart failure [6].

Generally, it is thought that asymptomatic diastolic dysfunction precedes overt heart failure, thus representing an ideal time for intervention [5]. A recent report from a population-based cohort of predominately Caucasian individuals showed that diastolic dysfunction was associated with development of heart failure within a 6-year follow-up period [7]. Nevertheless, little is known about progression of diastolic dysfunction over time in a predominately ethnic minority population with multiple cardiovascular risk factors to establish the proper window for intervention.

This study aimed to determine the rate of diastolic dysfunction progression over time and to identify factors predictive of changes in diastolic function using data from a retrospective cohort of predominately ethnic minority individuals.

2 Methods

A retrospective cohort was established from the echocardiogram database and the Electronic Health Record (EHR) system at the University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System. Individuals with echocardiograms positive for diastolic dysfunction during the study period (2006–2012) were selected; echocardiogram data was cross-referenced by medical record number to existing health records. The University of Illinois Institutional Review Board approved the study.

2.1 Participants

2.1.1 Inclusion Criteria

Any patient with two or more echocardiograms reporting diastolic dysfunction at anytime during the review period were eligible for inclusion in the study cohort to allow examination of progression rates (n = 154). Since the inclusion criteria were based upon presence of diastolic dysfunction on two or more echocardiograms during the study period, individuals with no evidence of diastolic dysfunction at time zero but who developed diastolic dysfunction on subsequent echocardiograms were included in the study cohort.

2.1.2 Exclusion Criteria

Only patients without echocardiogram evidence of diastolic dysfunction as well as those with only a single echocardiogram reporting diastolic dysfunction in the database during the review period were excluded from the cohort. Patients were not excluded on the basis of echocardiogram indication, inpatient or outpatient status, or presence of absence of cardiovascular risk factors including coronary artery disease. A random sample of 10 % of patients (n = 240) with only one echocardiogram in the database was drawn to assess potential selection bias. Based upon that sampling, our study cohort had a higher percentage of females (81 vs. 52 %), were smokers (76 vs. 38 %), and were older (31 vs. 2 % age >70). However the rates of diabetes were similar (61 vs. 62 %).

2.1.3 Cohort Study Variables

Baseline demographics, primary indication for the echocardiogram, co morbidities, clinical data (blood pressure, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and hemoglobin) and echocardiography parameters (left atrial size (LA), diastolic dysfunction grade, and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)) were recorded. Ethnic minorities were defined using the United States Census Bureau classification and included African Americans (62 %), Latinos (21 %), and Native American (0.7 %).

2.2 Echocardiograms

The study cohort was identified from the University of Illinois echocardiogram database and consisted of both inpatient and outpatient diagnostic studies. Diastolic function was assessed in a standardized method and in accordance to published guidelines using standard spectral Doppler and Tissue Doppler assessment. Individual echocardiograms were interpreted by the clinical cardiology attending assigned to the echocardiogram lab at the time of the study. Board certified cardiologists interpreted all echocardiograms and were subject to departmental quality review standards and procedures. Diastolic left ventricular function was reported as normal or abnormal. Primary measurements of mitral inflow included the peak early filling (E-wave) and the late diastolic filling (A-wave) velocities and the E/A ratio. Mitral inflow patterns were identified by the E/A ratio and included the following grading classification: (1) mild diastolic dysfunction (Grade 1, impaired relaxation with an E/A ratio >1); (2) moderate diastolic dysfunction (Grade 2, pseudo-normal LV filling with an E/A ratio >1 but less than 2); and (3) severe diastolic dysfunction (Grade 3, restrictive LV filling with an E/A ratio ≥2). Due to the retrospective nature of the study no intra and inter-observer reproducibility of echocardiographic measurements were available.

2.2.1 Echocardiogram Study Eligibility

Eligible was defined as the number of subjects with at least one follow- up echocardiogram after the baseline study in that time period. The study cohort was observed over a period ranging from 1.0 to 5.5 years per patient with an average of 2.6 years. Each patient had a mean (SD) of 4.4 (1.4) visits during that time. The number of visits ranged from 3 to 10. Patients’ diastolic dysfunction grade was abstracted from the echocardiogram data at the first assessment by the cardiologist and then recorded over subsequent echocardiograms reports.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Description of the cohort at their initial visit was done with respect to demographics, physical measures, medication use, medical history and echocardiogram parameters. Comparison of the patients whose diastolic dysfunction progressed to those who did not progress was done for continuous variables via t-tests or Wilcoxon two-sample tests, as appropriate; and for categorical variables via Pearson’s chi-square test of Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

Thirteen risk factors were considered for multivariate analysis: age, gender, body mass index, past medical history of diabetes, current tobacco use, use of Beta Blockers, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE Inhibitors), Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), calcium channel blockers (CCB), diuretics, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and left atrial (LA) size. Risk factors were selected based up the reviewed medical literature [8]. A backward stepwise elimination logistic regression procedure was performed with the criteria that a risk factor’s p-value be <0.20 to remain in the model to determine a multivariate model. A patient’s time to observation of progression, or if no progression occurred, the total time of observation was controlled for at each step. Both Likelihood-ratio and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests were used to assess model fit. For analysis all risk factors were dichotomized. Age was dichotomized at ≥65 (vs.<65) and BMI was dichotomized at BMI ≥25 (overweight or obese, vs. <25).

3 Results

3.1 Cohort Characteristics

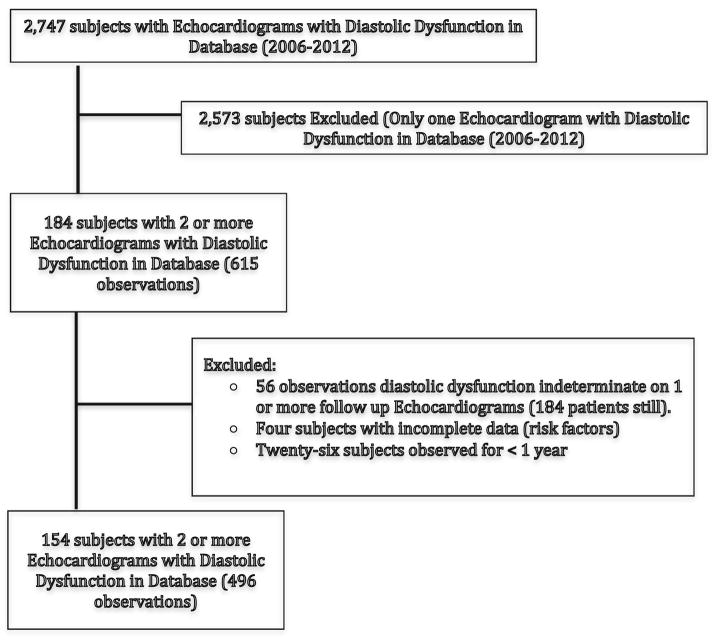

A retrospective cohort was established with 154 patients representing 496 echocardiograms performed within the study timeframe (Fig. 1). Analysis for potential selection bias between those selected for inclusion in the cohort and those excluded found that the study cohort was older, female and had a higher percentage of smokers as compared to those excluded from the cohort for having only one echocardiogram in the database. The primary indication for echocardiogram was chest pain followed by dyspnea and included both inpatient and outpatient studies. The study cohort was observed over a period ranging from 1.0 to 5.5 years per patient with an average of 2.6 years. Each patient had a mean (SD) of 4.4 (1.4) visits during that time. The number of visits ranged from 3 to 10. At the time of the initial echocardiogram, the mean age of the 154 study participants was 64.6 (SD, 10.1) years with a mean BMI 30.5 (SD, 7.4). There was a preponderance of females (124, 80.5 %) and ethnic minorities represented 83.7 % (n = 129) of the cohort. Significant percentages of participants were smokers and had diabetes respectively (n = 118, 76.6 %; n = 94, 61.0 %) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Selection criteria for retrospective cohort and study flow

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of retrospective cohort (2+ echo-cardiograms over a 6-year period)

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean(SD) | 64.6 (10.1) |

| Female, N (%) | 124 (80.5) |

| Race, N (%) | |

| African American | 96 (62.3) |

| Asian | 7 (4.6) |

| Caucasian | 18 (11.7) |

| Latino | 32 (20.7) |

| Native American | 1 (0.7) |

| Physical measures | |

| BMI, mean(SD) | 30.5 (7.4) |

| Systolic BP, mean (SD) | 136.1 (20.9) |

| Diastolic BP, mean(SD) | 74.8 (12.1) |

| BUN, mean (SD) | 18.6 (12.8) |

| Creatinine, mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.4) |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD) | 12.6 (1.6) |

| Medical history | |

| Smoker, N(%) | 118 (76.6) |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 94 (61.0) |

| Medication use | |

| Beta blockers, N (%) | 60 (39.0) |

| ACEI, N (%) | 99 (64.3) |

| ARB, N (%) | 94 (61.0) |

| Calcium channel blocker, N (%) | 107 (69.5) |

| Diuretics, N (%) | 73 (47.4) |

| Diastolic descriptors | |

| Emergency room use, N (%) | 75 (48.7) |

| LA size, N (%) | |

| Normal | 84 (54.6) |

| Mild | 49 (31.8) |

| Moderate | 21 (13.6) |

| Diastolic dysfunction, N (%) | |

| Grade 1 | 135 (87.7) |

| Grade 2 | 14 (9.1) |

| Grade 3 | 5 (3.3) |

| LVH, N (%) | 85 (55.1) |

| LVH Degree, N (%) | |

| Mild | 57 (37.0) |

| Moderate | 24 (15.6) |

| Severe | 4 (2.6) |

3.2 Changes in Diastolic Function

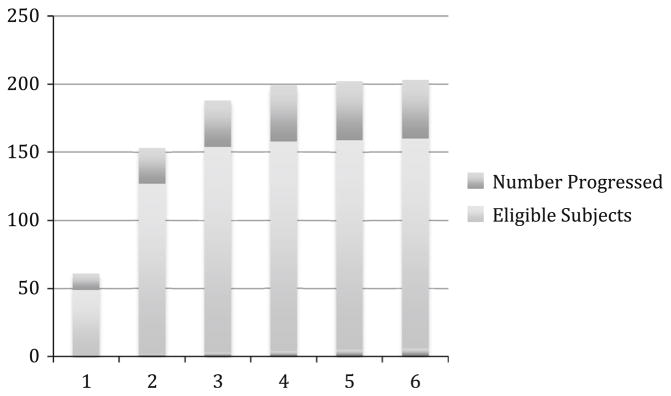

Diastolic function grade was reported in all subjects in the cohort. The majority of subjects had Grade I (mild) diastolic dysfunction at baseline; (n = 135, 87.7 %). Five percent of the cohort had normal diastolic dysfunction at the initial onset of the study observation period (n = 7). Approximately 9 % (n = 14) had Grade II diastolic dysfunction, and 3 % (n = 5) had Grade III diastolic dysfunction. Approximately 27.3 % (n = 42) of the study cohort demonstrated worsening grade of diastolic dysfunction in the study period (Fig. 2). Diastolic dysfunction grade was unchanged in 62.3 % (n = 96), improved in 9.7 % (n = 15), and worsened then improved in 0.7 % (n = 1). Any participant who demonstrated a worsening grade (42 who worsened only, 1 who worsened then improved) was considered to have progressed. Of the study cohort, 2.6 % (n = 4) developed echocardiographic evidence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) The highest percentage of diastolic dysfunction progression was noted in patients that were initially at Grade 1 at the start of the study observation period (26.6 % n = 34). There were 16 participants in the study cohort who regressed. All variables that were analyzed by progression status were analyzed by regression status and there was a significant age difference. Those who regressed had a mean (SD) age of 61.5 (8.8), whereas those who did not regress had a mean age of 67.8 (10.2), p = 0.0249.

Fig. 2.

Graph demonstrating progression rates among eligible patients by year. Eligible was defined as the number of subjects with at least one follow-up echocardiogram after the baseline study in that time period

3.3 Risk Factors Associated with Worsening Diastolic Function

Among these 154 participants, none of the risk factors examined were found to differ significantly between individuals who experienced progression of diastolic dysfunction and those without in a univariate risk factor analysis (Table 2). As no risk factor was significant in the univariate analysis, a multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess significant risk factors upon controlling for other risk factors, as we suspected confounding in the data. Using a stepwise backward elimination logistic regression, baseline use of calcium channel blockers (marginally significant, p < 0.10) and being African American (p < 0.05) appeared to be protective against diastolic dysfunction progression (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with and without diastolic dysfunction. P-values reflect either t-tests or chi-square tests, where appropriate, unless otherwise noted

| Progression N = 43 |

No Progression N = 111 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean(SD) | 62.8 (11.6) | 65.3 (9.4) | 0.1822 |

| Female, N (%) | 32 (74.4) | 92 (82.9) | 0.2341 |

| Race1, N(%) | 0.2307 | ||

| African American | 22 (51.2) | 74 (66.7) | |

| Asian | 3 (7.0) | 4 (3.6) | |

| Caucasian | 7 (16.3) | 11 (9.9) | |

| Latino | 10 (23.3) | 22 (19.8) | |

| Native American | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Physical measures | |||

| BMI, mean(SD) | 30.3 (6.6) | 30.6 (7.8) | 0.7917 |

| Systolic BP, mean(SD) | 137.6 (24.8) | 135.6 (19.3) | 0.6353 |

| Diastolic BP, mean (SD) | 73.1 (12.4) | 75.5 (11.9) | 0.2775 |

| BUN, mean (SD) | 18.5 (16.0) | 18.6 (11.3) | 0.993 |

| Creatinine, mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.2) | 0.7109 |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD) | 12.3 (1.3) | 12.8 (1.7) | 0.0603 |

| Medication use | |||

| Beta blockers, N (%) | 18 (41.9) | 42 (37.8) | 0.6461 |

| ACEI, N (%) | 29 (67.4) | 70 (63.1) | 0.6109 |

| ARB, N (%) | 26 (60.5) | 68 (61.3) | 0.9276 |

| Calcium channel blockers, N (%) | 27 (62.8) | 80 (72.1) | 0.2618 |

| Diuretics, N (%) | 18 (41.9) | 55 (49.6) | 0.3913 |

| Medical history | |||

| Smoker, N (%) | 33 (76.7) | 85 (76.6) | 0.9824 |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 24 (55.8) | 70 (63.1) | 0.4079 |

| Echocardiogram parameters | |||

| LA size, N (%) | 0.2156 | ||

| Normal | 23 (53.5) | 61 (55.0) | |

| Mild | 11 (25.6) | 38 (34.2) | |

| Moderate | 9 (20.9) | 12 (10.8) | |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy, N (%) | 19 (44.2) | 35 (61.5) | 0.1398 |

Fisher’s exact test

Table 3.

Results of multivariate modeling for risk factors for diastolic dysfunction progression

| Effect | p-value | Odds ratio reference | Odds ratio | 95 % Wald CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to progression observation or total observation time | 0.0058 | Each additional year of observation | 0.567 | (0.379, 0.849) |

| Gender | 0.1090 | Female vs. male | 0.454 | (0.173, 1.192) |

| CCB use | 0.1045 | Users vs. non users | 0.497 | (0.173, 1.192) |

| Diuretic use | 0.1945 | Users vs. non users | 0.599 | (0.276, 1.300) |

| African American | 0.0370 | AA vs. non-AA | 0.411 | (0.178, 0.948) |

| LVH | 0.0874 | LVH vs. non LVH | 2.054 | (0.900, 4.690) |

4 Discussion

Our study found a diastolic dysfunction grade progression rate of 27.9 % among this study cohort with significant percentages of tobacco use, obesity, and diabetes mellitus. Despite the presence of significant cardiovascular risk factor burden among this study cohort, the overall rate of diastolic dysfunction progression among the study cohort was similar to that observed in non-minority groups. Yet we found interesting racial/ethnic differences with African American race being protective against progression of diastolic dysfunction. This may explain while despite an overabundance of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, such as diabetes, obesity, and tobacco use in the study cohort, the progression rates were not higher. Nonetheless, the association between cardiovascular risk factor burden and development of diastolic dysfunction has been well established and prospective studies are needed to determine the impact of the presence of multiple cardiovascular risk factors on progression of diastolic dysfunction in different racial/ethnic groups.

A recent study by Paneni et al. [9] investigated the relationship between Type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndromes (defined as an insulin-resistant state resulting from a cluster of cardiovascular risk factors), and the overall impact on progression of biventricular dysfunction using tissue doppler. Findings suggest that patients with both diabetes and metabolic syndrome were at the highest risk for progression of chamber dysfunction towards heart failure and thus recommend that higher-risk individuals receive earlier and more aggressive treatment/management options to delay progression of chamber dysfunction.

A population-based cohort study in a predominately Caucasian population found that diastolic function grade worsened in 23.4 % of study participants during a four-year observation period, and diastolic dysfunction was associated with development of heart failure during 6 years of subsequent follow up [7]. Similar to this study, our study found significant diastolic dysfunction progression rates in the study cohort over a 4-year time frame with a mean time between repeated echocardiograms of 1.9 years. Nevertheless, this is first study to evaluate progression in a predominately minority population consisting largely of African Americans and Latinos.

Recent data have shown that diastolic function is a dynamic process with corresponding prognostic value [10]. Whereas worsening of diastolic function is associated with worse outcomes, improvement in diastolic dysfunction is associated with better survival [10]. Our study also found that 9.7 % of the study cohort had improvement in their diastolic dysfunction grade. In addition those with diastolic dysfunction regression were statistically significant younger than those without regression suggesting a role for early and aggressive intervention. Prospective studies are needed to determine the clinical relevance of improvement between grades of diastolic dysfunction.

Fischer et al. [11] reported that independent predictors of diastolic dysfunction included arterial hypertension, evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), obesity, diabetes, and coronary artery disease; however earlier studies have not evaluated risk factors associated with progression of diastolic dysfunction. Several studies have concluded that diastolic heart failure may be prevented by targeting selected cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, and obesity [10–12]. Our study cohort had significant percentages of tobacco use and obesity, thus representing a significant opportunity for cardiovascular risk factor modification. Similarly, a recent study by de Simone et al. [13] in a cohort of hypertensive individuals without prevalent cardiovascular disease found that the presence of LVH was associated with a higher risk of diastolic dysfunction than individuals with normal left ventricular mass. Our study found in multivariate modeling that having LVH marginally increased the odds of diastolic dysfunction progression. Left ventricular hypertrophy is one of the strongest predictors of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in a hypertensive population and treatment of hypertension greatly attenuates the development of LVH [13, 14]. Studies have shown that in patients with established LVH, disease regression is possible thus providing an objective target for monitoring the effectiveness of clinical interventions [14].

Based upon current literature, diastolic dysfunction appears to represent an early marker of subclinical cardiovascular disease [5, 15]. There is increasing evidence demonstrating the independent predictive value of diastolic dysfunction [15]. Further studies should replicate this in other minority populations and then prospectively study whether any of these risk factors can be modified and if so does that slow the progression of diastolic dysfunction.

5 Limitations

Limitations in this study include a retrospective study design specifically the variability in the timing of repeated echocardiograms. There were a significant number of subjects excluded from the final analysis due to lack of a repeat echocardiogram in the database. Due to differences in selected cardiovascular risk factors, and the demographics of the cohorts, we cannot exclude sample bias created as a result of those subjects excluded. The small number of subjects that had more than one echocardiogram and the increased numbers of females and older age of the study cohort limits the generalizability of these findings.

6 Conclusion

Our study showed sizable rates of diastolic dysfunction progression in this predominately ethnic minority population, similar to findings of previous study in a non-minority population. Further studies to examine the role of cardiovascular disease risk factors in accelerating progression rates from asymptomatic diastolic dysfunction to symptomatic stages is paramount for optimizing intervention strategies.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR000050. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Contributor Information

Heather M. Prendergast, Email: hprender@uic.edu, University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, IL, USA. Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Room 471-H College of Medicine East, 808 South Wood Street, Chicago, IL 60612-7354, USA

Samuel Dudley, Brown University Section of Cardiology, Providence, RI, USA.

John Kane, Rush Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Martha Daviglus, University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, IL, USA.

Jared Marcucci, University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, IL, USA.

Anthony Acosta, Resurrection Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

E. Bradshaw Bunney, University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, IL, USA.

Dejuran Richardson, Rush Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Tamara O’Neal, University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

- 1.Joynt K, Oray E, Jha A. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305:675–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barretto A, Del Carlo C, Cardoso J. Hospital readmissions and death from Heart Failure-rates still alarming. Arg Bras Cardiol. 2008;91:335–41. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2008001700009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borlaug B, Redfield M. Diastolic and systolic heart failure are distinct phenotypes within the heart failure spectrum. Circulation. 2011;123:2006–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.954388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood P, Piran S, Liu P. Diastolic heart failure: progress, treatment challenges, and prevention. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:302–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogel M, Slusser J, Hodge D, et al. The natural history of pre-clinical diastolic dysfunction. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:144–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moe G, Tu J. Heart failure in the ethnic minorities. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25:124–40. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328335fea4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane G, Karon B, Mahoney D, et al. Progression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and risk of heart failure. JAMA. 2011;306:856–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo C, Jin Z, Homma S, et al. Race/ethnic disparities in left ventricular diastolic function in a triethnic community cohort. Am Heart J. 2010;160:152–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paneni F, Gregori M, Tocci G, et al. Do diabetes, metabolic syndrome or their association equally affect biventricular function? A tissue Doppler study. Hypertension Res. 2013;36:36–42. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alijaroudi W, Alraises M, Halley C, et al. Impact of progression of diastolic dysfunction on mortality in patients with normal ejection fraction. Circulation. 2012;125:782–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer M, Baessler A, Hense H, et al. Prevalence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in the community. Results from a Doppler echocardiographic-based survey of a population sample. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:320–8. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Lainchbury J, Senni M, et al. Diastolic heart failure in the community: clinical profile, natural history, therapy, and impact of proposed diagnostic criteria. J Cardiac Fail. 2002;8:279–87. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.128871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Simone G, Kitzman D, Chinali M, et al. Left ventricular concentric geometry is associated with impaired relaxation in hypertension: the HyperGEN study. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1039–45. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gradman A, Alfayoumi F. From left ventricular hypertrophy to congestive heart failure: management of hypertensive heart disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;48:326–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aljaroudi W, Thomas J, Rodriguez L, et al. Prognostic value of diastolic dysfunction: a state of the art review. Cardiol Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e31829cf733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]