Abstract

The Social Information Processing (SIP) model postulates that parents undergo a series of stages in implementing physical discipline that can escalate into physical child abuse. The current study utilized a multimethod approach to investigate whether SIP factors can predict risk of parent-child aggression (PCA) in a diverse sample of expectant mothers and fathers. SIP factors of PCA attitudes, negative child attributions, reactivity, and empathy were considered as potential predictors of PCA risk; additionally, analyses considered whether personal history of PCA predicted participants’ own PCA risk through its influence on their attitudes and attributions. Findings indicate that, for both mothers and fathers, history influenced attitudes but not attributions in predicting PCA risk, and attitudes and attributions predicted PCA risk; empathy and reactivity predicted negative child attributions for expectant mothers, but only reactivity significantly predicted attributions for expectant fathers. Path models for expectant mothers and fathers were remarkably similar. Overall, the findings provide support for major aspects of the SIP model. Continued work is needed in studying the progression of these factors across time for both mothers and fathers as well as the inclusion of other relevant ecological factors to the SIP model.

Keywords: child abuse potential, social information processing model, history of abuse, cognitive risk factors, transition to parenting

Child physical maltreatment constituted 18% of cases substantiated by child protective services in 2013, second only to neglect (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2015). Yet concerns about false negatives in child protective services permeate the field, with DHHS estimates widely viewed as capturing the proverbial “tip of the iceberg” (e.g., Sedlak et al., 2010). Compelling evidence supports that DHHS statistics consistently underestimate the scope of maltreatment, particularly with respect to physical abuse (Sedlak et al., 2010). Moreover, outcomes for children who are not substantiated in maltreatment investigations do not differ from those who are substantiated (Hussey et al., 2005). Therefore, substantially more harmful parent-child aggression appears to damage the lives of more children than solely what protective services agencies identify and substantiate.

Physical child abuse can thrive within an atmosphere that accepts, and largely condones, varying levels of physical aggression implemented by parents toward children. Parental physical discipline toward children remains virtually ubiquitous in this country (e.g., nearly two-thirds of parents report recently spanking their 3-year-old; Taylor, Lee, Guterman, & Rice, 2010). Parents who spank are nearly three times more likely to engage in harsh discipline analogous to physical abuse (Zolotor, Theodore, Chang, Berkoff, & Runyan, 2008), and parental spanking of children at age one predicts later child protective services involvement (Lee, Grogan-Kaylor, & Berger, 2014). Maltreatment often transpires when parents inadvertently intensify physical discipline (Whipple & Richey, 1997). The spectrum of physical parent-child aggression (PCA) behavior can thus be viewed as occurring along a physical discipline-child abuse continuum, wherein physical abuse differs quantitatively, not qualitatively, from physical discipline (e.g., Greenwald, Bank, Reid, & Knutson, 1997; Rodriguez, 2010a; Straus, 2001). On such a physical discipline-abuse continuum, excessive “sub-abusive” physical discipline intensifies and escalates into abuse at some point along this continuum, potentially including tactics that constitute some of those unsubstantiated reports of abuse. Such a conceptualization underscores the need to clarify the full span of PCA behaviors as well as the evolution of PCA before it progresses to physically abusive behavior.

To estimate the probability one will approach or cross into the abusive end of such a continuum, risk assessment tools approximate the likelihood of abuse, termed child abuse potential (Milner, 1994). Child abuse potential assesses interpersonal and intrapersonal difficulties observed in parents who physically maltreat their children (Milner, 1986). Child abuse potential has been linked to more severe physical aggression toward children (Rodriguez, 2010a) and more coercive and authoritarian parenting approaches (Haskett, Scott, & Fann, 1995; Margolin, Gordis, Medina, & Oliver, 2003; Rodriguez, 2010a). Consistent with a PCA continuum perspective, the evidence suggests that parents who engage in harsher, more frequent physical discipline are more likely to exhibit greater abuse potential and accelerate to abusive parenting. This inclusive conceptualization of PCA was adopted in this study to try to capture, as broadly as possible, the range of parent-child aggression that could culminate in elevated child abuse risk.

Theoretical Approach

To understand how physical discipline may spiral into abuse, we must consider a range of complex processes and factors. One model focusing on the cognitive components is Social Information Processing (SIP) theory, delineated by Milner (1993, 2000). Although SIP has been utilized to describe a number of interpersonal processes, SIP as applied to PCA risk focuses on the potential processes whereby parents’ cognitions may guide their decision to engage in PCA that could become abusive. SIP proposes that pre-existing cognitive schemas (e.g., a parent’s child- and discipline-related beliefs) exist prior to a parent processing information from any given new parent-child interaction, setting the stage for how he or she may approach discipline events when they occur. Then, when encountering a new discipline situation, four processing stages begin. The parent must first accurately perceive the situation; factors that distract and interfere with a parent’s ability to attend accurately to the situation would increase PCA risk (Stage 1). In Stage 2, the parent interprets and evaluates the child’s behavior in the situation; if a parent has inaccurately perceived the situation, she or he may evaluate the child’s behavior harshly, adopting negative biases toward the child in the situation. In the third stage, at-risk parents may then fail to integrate potentially mitigating information that could explain the child’s behavior and mollify such negative biases, thereby influencing the options they consider appropriate for disciplining the child. Finally, parents who then select PCA would encounter difficulty monitoring their administration of physical discipline in the final cognitive-behavioral stage (Stage 4). This SIP model thus hypothesizes parents proceed through a series of cognitive stages that lead them to engage in PCA. The SIP model fits well with cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches, rendering this approach applicable to intervention.

Relatively few studies have considered elements of the SIP model as a whole, although findings to date provide support for the model with mothers (e.g., McElroy & Rodriguez, 2008; Rodriguez, 2010b), with virtually no consideration of the model with fathers (Rodriguez & Richardson, 2007 included a small sample of fathers). One study of mothers considered several SIP elements independently but not collectively (Montes, DePaul, & Milner, 2001). However, various elements of the model have been implicated in a number of studies. In terms of pre-existing schema, which typically include PCA and discipline beliefs that can predate parenthood, those who approve of more severe forms of discipline would theoretically be at higher risk to become physically abusive during a parent-child disciplinary exchange (Bower-Russa, 2005). Research highlights the importance of the acceptability of physical discipline in predicting its use by mothers (Ateah & Durrant, 2005).

With regard to Stage 1, processes that interfere with accurate perceptions are involved, which has been construed to include overreactivity that interferes with careful consideration of the discipline situation (Milner, 2000). High reactivity is associated with abuse risk (Stith et al., 2009). Consistent with the classic hypothesis that frustration promotes aggression (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939), those who overreact to frustrating events and cannot manage their negative affect may be at increased risk to engage in PCA (Robyn & Fremouw, 1996). The most well-researched aspect of the SIP model involves Stage 2 processes, such as interpreting the situation negatively in terms of biases toward the child. Abusive mothers tend to make negative hostile-intent attributions about children’s behavior (Haskett, Scott, Willoughby, Ahern, & Nears, 2006), as do high abuse-risk mothers (Montes et al., 2001). Pregnant women’s hostile attributions about children were also later associated with increased odds of harsh parenting and later maltreatment (Berlin, Dodge, & Reznick, 2013). Stage 2 thus includes negative attributions that impact a parent’s potential justification for their discipline decision. Recent research also suggests that high PCA-risk parents not only make such negative attributions but are also less likely to incorporate mitigating information that would reduce the likelihood of PCA (Irwin, Skowronski, Crouch, Milner, & Zengel, 2014), which reflects Stage 3. Such mitigating information may be more accessible when parents empathize with what their child is experiencing. Empathy with the child’s perspective can facilitate modifying negative attributions ascribed to the child, allowing a parent to integrate situation-specific information that could mitigate a child’s perceived culpability (Jones, 2006; Milner, 2000). The capacity to experience empathy for others inhibits aggression (Richardson, Hammock, Smith, Gardner, & Signo, 1994) and low empathy toward children has been observed in abusive mothers (Mennen & Trickett, 2011) as well as high-risk parents (Perez-Albeniz & De Paul, 2004).

Role of History

Aside from the SIP model factors, a significant aspect that has long been viewed to elevate abuse risk involves a personal history of PCA. Despite widespread acceptance of the classic phenomenon referred to as the intergenerational transmission of violence hypothesis (Curtis, 1963; Straus, 1983), researchers caution against an immutable cycle of violence claim because the majority of parents with harsh discipline histories do not become harsh disciplinarians (e.g., Kaufman & Zigler, 1987; Widom, 1989). Being a recipient of childhood physical abuse is no longer considered necessary or sufficient to becoming physically abusive as a parent. Nonetheless, several studies support a connection between abuse as a child and becoming abusive as a parent (see Stith et al., 2009, for review). A history of trauma has been associated with increased child abuse potential (Craig & Sprang, 2007), and adverse childhood experiences have been linked to mothers’ later abuse-risk attitudes and infant spanking (Chung et al., 2009). This cycle of violence may arise from mothers’ bias toward aggressive solutions (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011). Similarly, a poor relationship with one’s parents is a related risk factor for abuse (Stith et al., 2009), wherein low parental nurturance experienced during childhood may also increase risk. Thus, in the present study, family history is conceptualized inclusively to reflect the experience of abusive experiences in childhood as well as harsh versus nurturant parenting.

However, family history itself may not directly predict PCA but through its influence on other processes. Historical factors, such as abuse, parenting style, and support, must operate in some manner to escalate parents’ risk of PCA. Potentially the mechanisms underlying this connection in part reflect how history affects the development of cognitions, particularly attributions (Kolko et al., 2002) and familiarity with harsh techniques (Rodriguez & Sutherland, 1999) that might foster approval of those approaches. For example, although mothers’ history of abuse was related to later use of abuse as a parent, this same study did not identify hostile attributions towards adults as a mediator (Berlin et al., 2011); this study did not consider negative attributions specific to children and thus contradicts the substantive research that does identify negative attributions as characteristic of PCA risk. Another study did not identify personal abuse history to be a risk factor for abuse among pregnant or recently delivered adolescents, but did find abuse risk elevated for those who value corporal punishment (Haskett, Johnson, & Miller, 1994).

Overall, research has yet to pinpoint mechanisms whereby history confers elevated risk. For example, attitudes regarding PCA may be learned in childhood from one’s own discipline, pre-existing schema activated proximally when a parent faces a disciplinary decision. Because they received the discipline themselves, parents may justify their harsh treatment by adopting negative attributions to warrant their punishment use. Consequently, the current study considered whether a history of childhood abuse, harsh parenting style, and low childhood support elevate later abuse risk by allowing parents to view PCA as acceptable and by judging the child harshly with negative attributions.

Sample Considerations

Prior research has considered abuse risk in expectant parents in an effort to understand processes prior to parenting (e.g., Cerny & Inouye, 2001; Moore & Florsheim, 2008). Yet much remains unanswered in predicting PCA, particularly in samples that are not very high risk (e.g., Erickson & Tonigan, 2008); none have yet considered the SIP processes collectively. Targeting first-time parents is critical in evaluating the cognitive schemas that are “pre-existing,” predating parenthood. If specific elements are identified as critical to increasing risk, altering such cognitions preventatively, prior to childbirth, becomes urgent.

In addition, research continues to overlook the call of many who have long urged researchers to include fathers (e.g., Milner & Dopke, 1997; Stith et al., 2009). The field has yet to identify factors relevant to fathers specifically (Guterman & Lee, 2005), often even relying on mothers to provide insight into fathers (e.g., Lee, Kim, Taylor, & Perron, 2011). Indeed, fathers appear particularly likely to engage in the most serious PCA (Brewster et al., 1998) and constitute a significant percentage of substantiated abusers (DHHS, 2015). But minimal literature guides what constitutes paternal abuse risk. Preliminary evidence suggests fathers demonstrate risk profiles comparable to mothers, with minor differences (e.g., Schaeffer, Alexander, Bethke, & Kretz, 2005; Sidebotham et al., 2001), although the role of historical variables in paternal abuse risk is unclear (Guterman & Lee, 2005). High abuse-risk fathers, but not high-risk mothers, reported less empathic perspective-taking ability (Perez-Albeniz & De Paul, 2004). One study included some SIP-relevant components to predict mother’s and father’s PCA independently, with reasonable consistency between mothers’ and fathers’ SEM models, including negative child attributions and PCA approval (Smith Slep & O’Leary, 2007). Overall, the limited findings speculate fathers might share some features in common with mothers, although few direct, comprehensive comparisons have been drawn.

Methodological Issues

Methodological limitations have historically hampered researchers who have relied on the child abuse reporting system, with its high false negatives, or on self-report methods, with their potential for participant bias. Parents may represent themselves, intentionally or subconsciously, in a favorable way. Direct self-report is an explicit assessment of a variable of interest, whereas analogs are implicit means designed to minimize response bias (Fazio & Olson, 2003). The variable is assessed in a manner analogous to the construct but the participant is not explicitly aware of the intent of the task or its scoring. Analogs represent a promising means to assess variables most susceptible to misrepresentation (like PCA risk and its predictors; DeGarmo, Knutson, & Reid, 2006). Analog tasks vary in the extent to which the participant is aware of how and what is being assessed (Fazio & Olson, 2003), varying on the degree to which automatic, unconscious processing is tapped. The more conscious the level of processing required in the task, the greater the risk responses could be misrepresented. Analog strategies were incorporated in this study to strengthen our understanding of the role of selected model components in predicting PCA risk.

Current Investigation

The current study applies SIP theory to predict PCA risk in a diverse sample of expectant mothers and fathers using a rigorous, multimethod approach. A comprehensive approach combining multiple SIP factors across stages was adopted. Attitudes accepting of harsh physical discipline (pre-existing schema) and reactivity that can interfere with accurate perceptions (Stage 1) were expected to predict negative child attributions (Stage 2), with greater empathy (Stage 3) potentially influencing such negative attributions; negative attributions then would lead to increased PCA risk, which was considered higher child abuse potential, more expected authoritarian parenting, and inclination to punish expected noncompliant child behavior. Thus, the current study examines a comprehensive theoretically-grounded model for expectant mothers and begins the development of sorely needed, theoretically-driven models for fathers. Given preliminary evidence of consistency in parent models (Smith Slep & O’Leary, 2007), no specific gender differences were proposed. The study also considered the role of personal history of abusive and harsh parenting in exacerbating PCA risk. History was hypothesized to exert primarily indirect effects on PCA risk via its impact on SIP components, namely on its effect on the emergence of attitudes endorsing PCA and on negative child attributions. The direct effect of history was considered to evaluate whether history’s effect on abuse risk was significant apart from these hypothesized indirect paths.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 108 primiparous women and 84 male partners. These fathers represented 90.3% of the 93 identified fathers who were available to participate (e.g., other fathers were deployed, out-of-state, incarcerated, or otherwise not available before the child’s birth); all but one were biological fathers of the child. Average age for expectant mothers was 25.38 years (SD = 5.73, range 17–39) and 28.11 years for expectant fathers (SD = 5.95, range 18–48). For racial/ethnic identification, 51.9% of expectant mothers identified as African-American, 45.4% as Caucasian, 2% as Native American/Alaskan, 1% as Asian; an additional 2% of the sample of mothers indicated considering themselves Hispanic/Latina. For expectant fathers, 51.2% identified as African-American and 48.8% as Caucasian, with 2.4% of the total also identifying as Hispanic/Latino. Of the 108 mothers, 86% were currently in a relationship with the father of the expected child. For educational level, 36% of expectant mothers had a high school diploma or less, with 18.5% having some college or vocational training, another 18.5% having a college degree, with the remainder having degrees beyond a bachelor’s degree. For expectant fathers, 31% had a high school diploma or less, with 20.2% with some college or vocational training, 26% with a college degree, and the remainder earning beyond a college degree. Over 48% of expectant mothers were receiving federal public assistance, with 50% reporting a median annual household income below $30,000. Over half of the mothers indicated they were unemployed, but most expectant fathers (83.3%) reported they were employed.

Measures

Multiple measures and scores were identified for each model component, as specified below; all internal consistencies appear in Table 1 for both mothers and fathers separately.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Sample Internal Consistencies for Measures for Mothers and Fathers

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | α | Mean | SD | α | |

|

| ||||||

| History | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| PAQ History Maternal Authoritarian | 35.22 | 6.68 | .85 | 36.26 | 6.75 | .84 |

| PAQ History Maternal Authoritative | 34.82 | 8.35 | .75 | 34.70 | 8.45 | .73 |

| CTSPC History Physical Assault | 37.87 | 46.44 | .84 | 45.59 | 43.09 | .78 |

| CTSPC History Psychological | 32.13 | 29.80 | .75 | 37.36 | 28.87 | .67 |

|

| ||||||

| PCA Attitudes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| AAPI Corporal Punishment Attitudes | 31.37 | 8.63 | .83 | 31.87 | 9.06 | .82 |

| Physical Abuse Vignettes Severity | 24.03 | 3.63 | .63 | 23.48 | 4.33 | .68 |

| Physical Abuse Vignettes Definition | 5.64 | 1.39 | .53 | 5.41 | 1.67 | .78 |

| Physical Abuse Vignettes Reporting | 4.75 | 1.40 | .51 | 4.57 | 1.73 | .71 |

| PCA Acceptability Movie Task | 18.17 | 10.61 | .76 | 18.13 | 12.38 | .81 |

|

| ||||||

| Attributions | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Video Rating Minimization | 3.09 | .79 | .94 | 3.15 | .71 | .79 |

| Video Rating Negative Attribution | 3.59 | .42 | .83 | 3.61 | .41 | .89 |

| Infant Cry Quest Minimization | 2.37 | .62 | .73 | 2.44 | .69 | .79 |

| Infant Cry Quest Directive Control | 3.35 | .79 | .84 | 3.31 | .79 | .83 |

| Plotkin Vignettes Attribution Total | 40.57 | 16.71 | .85 | 37.07 | 16.28 | .87 |

|

| ||||||

| Reactivity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Negative Mood Regulation Scale | 64.37 | 17.15 | .87 | 64.37 | 17.21 | .85 |

| Frustration Discomfort Scale | 18.36 | 5.42 | .84 | 17.04 | 5.51 | .86 |

| PASAT b | 80.91 | 70.93 | 84.01 | 72.71 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Empathy | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| IRI Empathic Concern | 29.18 | 4.28 | .71 | 26.94 | 4.31 | .63 |

| IRI Perspective Taking | 26.56 | 4.77 | .77 | 26.24 | 4.88 | .75 |

|

| ||||||

| PCA Risk | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Child Abuse Potential Inventory a | 97.97 | 76.09 | 89.49 | 57.84 | ||

| Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory | 101.88 | 18.38 | .87 | 109.32 | 20.52 | .90 |

| ReACCT Intentional Noncompliance | 3.84 | 9.73 | .75 | 4.94 | 9.98 | .77 |

| PAQ Expected Authoritarian Parenting | 34.08 | 6.62 | .80 | 34.35 | 7.24 | .84 |

Note. PAQ = Parental Authority Questionnaire; CTSPC = Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale; AAPI = Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory; IRI = Interpersonal Reactivity Index; ReACCT = Response Analog to Child Compliance Task

The Child Abuse Potential Inventory items are variably weighted thus alpha was not computed.

No alpha because the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task value is a single value, the number of trials attempted.

Historical background

The Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTSPC; Straus et al., 1998) was administered retrospectively, asking respondents to indicate the frequency with which they personally experienced 22 items (response categories: 0 = this has never happened; 1 = once; 2 = twice; 3 = 3–5 times; 4 = 6–10 times; 5 = 11–20 times; 6 = more than 20 times). Responses are scored based on the frequency range reported by the parent: responses of 0, 1, and 2 correspond to scores of 0, 1, and 2, respectively; a score of 4 (the midpoint) is assigned for a parent selecting the 3–5 times category; a score of 8 is assigned to the 6–10 times category; a score of 15 is assigned for the 11–20 times category; and a score of 25 is given for the final category, 20 or more times. Thirteen of the CTSPC items directly address varying levels of physical tactics applied toward children, comprising a subscale entitled Physical Assault (with subcategories of minor assault/corporal punishment, severe assault/physical maltreatment, and very severe assault/severe physical maltreatment, which range from spanking to beating up or burning). Five additional items contribute to the Psychological Aggression subscale (involving such behaviors as verbal threats and yelling). Thus, for both tactic categories, higher scores indicate greater frequency.

The Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ; Buri, 1991) is a 30-item measure of parenting style in which the participant reports on how they were raised by their caregiver. Ten items for each style were presented in a Likert format from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. For this study, the respondents’ reports on maternal authoritarian parenting as well as more supportive maternal authoritative parenting were extracted for analysis. Scores were oriented such that higher scores indicate the participant believed they received more of that parenting style from their maternal caregiver.

PCA attitudes

The Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory-2 (AAPI; Bavolek & Keene, 2001), Form A (a different version than used for PCA Risk below), includes a Value of Corporal Punishment scale, with 11 items to provide an assessment of parents’ beliefs regarding the acceptability of physical discipline. Questions are posed in a 5-point Likert format, from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree, with scores oriented such that higher scores suggest greater endorsement of physical discipline of children.

The Physical Abuse Vignettes (PAV; Shanalingigwa, 2009) include eight different vignettes of parent-child behavior depicting various levels of PCA, ranging from hitting a child without bruising to burning with a cigarette. Participants are asked to indicate: (1) whether they view the parental response as maltreatment (Yes/No), summed across the 8 vignettes for a Definition score; (2) how serious they rate the parental behavior on a 4-point Likert scale, summed across the 8 vignettes for a Severity Rating score; and (3) whether they would report the event to child protection (Yes/No), summed across the 8 vignettes for a Reporting scale. For all three scales, higher scores indicate less acceptance of PCA.

The Parent-Child Aggression Acceptability Movie Task (Parent-CAAM Task; Rodriguez, Russa, & Harmon, 2011) is an analog task to implicitly assess attitudes, consisting of eight 90-sec movie clips depicting varying levels of PCA (five physical abuse, three physical discipline). Participants are asked, based only on that scene, to stop the video if and when they believe the scene has become physically abusive. Scores are derived from the number of seconds until the parent makes a decision to halt the video. Because time spent processing socially desirable responses would delay response time, slower response time in judging a scene as abusive was conceptualized as indicating greater acceptability of PCA.

Reactivity

The Negative Mood Regulation Scale (NMRS; Catanzaro & Mearns, 1990) is a 30-item measure of emotion regulation emphasizing one’s ability to restore emotional balance after experiencing distress. Items are presented in a 5-point Likert scale format from (1) strongly agree to (5) strongly disagree; higher scores indicate poorer emotion regulation ability.

The Frustration Discomfort Scale (FDS; Harrington, 2005) includes seven items relating to intolerance of discomfort and frustration, rated on a 5-point Likert scale from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Items were summed such that higher scores indicate poorer frustration tolerance.

The computerized Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT; Schloss & Haaga, 2011) is based on a cognitive test that can also be conceptualized/scored as an implicit measure of frustration tolerance. Participants were presented with a series of numbers one at a time for 3.5 seconds; they add each new number to the previous number and click the sum displayed on the screen. They then must ignore the sum and add a new number to the previous number. Participants are notified if they select the correct sum but an aversive sound blasts occurs for slow or incorrect sums. After a practice phase, participants proceed with test trials. Cognitive performance was not of interest to this study. Instead, a prominent “QUIT” button is on display; they are instructed at the outset that they can discontinue trials by selecting the button. Scores are thus the number of trials attempted (possible total number 172, for ten minutes).

Negative child attributions

The Plotkin Child Vignettes (PCV; Plotkin, 1983) measure perceptions of the intentional misbehavior of children (Haskett et al., 2006); for 18 vignettes, respondents indicate how much they believe the child in the scene behaved to intentionally annoy the parent on a 9-point Likert scale, from (1) did not mean to annoy me at all to (9) the only reason the child did this was to annoy me, where higher scores suggest more negative child attributions.

The Infant Crying Questionnaire (Haltigan et al., 2012) is a measure of global beliefs about infant crying in which parents are asked to indicate what they believe about infant crying and what they want to achieve when an infant cries, including both infant-oriented and parent-oriented items. The ICQ contains 43 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from (1) never to (5) always. Two subscales were extracted for this study: the Minimization scale (nine items that include thinking of crying as manipulation or nuisance), and the Directive Control scale (eight items on their responses to crying, such as teaching them not to “throw a fit”), with both scales scored such that higher scores indicate more negative crying attributions.

The Video Ratings (Leerkes & Siepak, 2006) involve respondents viewing two 1-minute videos of babies in distress while playing with a toy; each video was followed by 18 questions on a 4-point Likert scale regarding their attributions for the baby’s crying. Two scales were extracted: Negative Internal Attributions (six items each video, including perception of the baby as spoiled or unreasonable) and Minimizing Attributions (five items for each video, such as the child having a bad day). Scores on both subscales were oriented such that higher total scores suggest less negative crying attributions.

Empathy

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1980, 1983) is an assessment of empathic abilities with two relevant subscales: an Empathic Concern scale, the ability to affectively connect and sympathize, and a Perspective Taking scale, assuming the psychological perspective of others. Each subscale includes seven items rated from (1) does not describe me well to (5) describes me very well, such that higher scores indicate greater empathy.

PCA risk dependent variable

The Child Abuse Potential Inventory (CAPI; Milner, 1986), a leading abuse risk instrument, consists of 160 items posed in an Agree/Disagree format. Only 77 of these items are variably weighted to contribute to the Abuse Scale score, with higher scores indicative of greater abuse risk. The Abuse Scale involves characteristics identified in parents with substantiated physical abuse, including the following subscales: Distress, Rigidity, Unhappiness, Problems with Child and Self, Problems with Family, and Problems with others. The CAPI has been extensively used to screen abusive parents, with scores correctly classifying 89.2% of abusers and 96.3% of controls (Milner et al., 1986).

Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory-2 (AAPI; Bavolek & Keene, 2001) Form B was used as an additional measure of abuse potential, assessing the beliefs and behaviors regarding child-rearing that characterize abusive parenting, with scores significantly discriminating abusive from comparison parents. This measure includes 40-items on a 5-point Likert scale from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree, with total scores oriented such that higher scores suggest greater abuse risk.

An Expected Parental Authority Questionnaire (a modified PAQ; see above) was administered in future tense, asking expectant parents to indicate how they expect to raise their impending child. Participants received comparable questions to the retrospectively worded PAQ, with the 30 items covering the three parenting styles. For this study, Expected Authoritarian parenting was selected for inclusion in the dependent variable, with higher scores indicative of more authoritarian parenting.

The Response Analog to Child Compliance Task (ReACCT; Author citation) is an analog selected to contribute to the PCA risk construct. This computerized task simulates a realistic parent-child situation and prompts the respondent for decisions they might implement for child compliance and non-compliance. Parents are asked to imagine in the future, they are running late one morning and need to guide their child to get ready to leave home for preschool. The task involves 12 scenes in which the parent reads an instruction they presumably provided to the child to complete an activity (e.g., get out of bed) and the child is depicted as either complying or not complying (some scenes, multiple non-compliances). The participant hears and sees a ticking clock to simulate time urgency of how late they now are; each time the child complies, the parent receives a game bonus of 50 cents. After reading the child response (compliance or noncompliance) to the hypothetical parent instruction, the parent selects from 16 possible response options, some of which are adaptive (e.g., praise for compliance) whereas others involve PCA (e.g., spanking, hitting with an object). Adaptive responses receive positive weights whereas non-adaptive responses receive negative weights. Scores of interest are the total number of non-adaptive/physical strategies used in intentional noncompliance scenes (nine items), where higher scores are harsher.

Procedure

Participants were families drawn from an ongoing longitudinal study—“Following First Families: Triple-F”—that investigates the development of PCA risk in first-time families, conducted in a large, urban city in the Southeast. This sample represents the first set of families enrolled in the first wave of the study. Participants were recruited from flyers distributed at local hospitals’ obstetric/gynecological clinics and affiliated childbirth courses. Interested primiparous expectant mothers in the final trimester of their pregnancy contacted the lab to arrange a 2-2 ½ hour session for themselves, and wherever possible, their partner. For inclusion in the sample, the expectant father was required (based on mother and father report) to expect to be involved in the child’s upbringing, but the mother was not required to be in an ongoing relationship with the father. Sessions were conducted in-home whenever possible to maximize participant convenience unless the participant expressed a preference for a lab session or there was insufficient space for completion of the protocol in their home. Separate, private rooms were required to ensure that mothers completed the protocol independently of their partner. All measures were delivered electronically on laptop computers and were completed with headphones. Upon completion of the protocol, each participant (mother and father separately) was compensated with a $60 gift card. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all procedures in the longitudinal study.

Analytic Plan

We evaluated the SIP model’s predictions using dyadic path analysis. These models were estimated using Mplus 7.3, using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. Three sets of path models were estimated: one for mothers, one for fathers, and a dyadic model incorporating both mothers and fathers. The dyadic path models can accommodate the nesting introduced by having both members of the couple in the model (Peugh, DiLillo, & Panuzio, 2013; Wendorf, 2002). For each SIP factor, composites were created by standardizing each variable and then averaging the standardized scores; the variables for mothers and fathers were standardized separately. Composites were comprised of the following scores: PCA Risk (CAPI Abuse Scale, AAPI Total, ReACCT Noncompliance, Expected PAQ Authoritarian); History (CTSPC Physical Assault and Psychological Aggression, PAQ Authoritarian, PAQ Authoritative); Attitudes (Abuse Vignettes Definition, Reporting, and Severity; AAPI Corporal Punishment, Parent-CAAM); Reactivity (Frustration Discomfort, PASAT, NMRS); Empathy (IRI Empathic Concern and Perspective Taking); Attributions (Video Rating Minimization and Directive Control, ICQ Negative Attribution and Minimization, Plotkin Attribution).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Participant means and standard deviations are displayed in Table 1. Notably, the sample as a whole obtained mean CAPI Abuse Scale scores and AAPI-2 Total scores within normal limits. Although not the focus of our research questions, the correlations for all measures, separately for both mothers and fathers, are in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlations between Measures for Mothers and Fathers

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. | 18. | 19. | 20. | 21. | 22. | 23. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | −.07 | .30** | .38*** | .37*** | −.04 | −.13 | −.13 | .16 | −.08 | −.07 | .23* | .21* | .15 | −.09 | −.08 | .24* | .09 | .04 | .22* | .44*** | .32** | .64*** | |

| 2. | −.27** | −.23* | −.08 | .01 | .15 | −.01 | .04 | .05 | −.01 | −.01 | .06 | .28** | −.01 | −.17 | −.23* | −.11 | .29** | .24* | −.17 | .01 | −.02 | .11 | |

| 3. | .30** | −.49*** | .71*** | .42*** | −.25* | −.25* | −.30** | .18 | .02 | −.07 | −.15 | .09 | .07 | −.24* | −.08 | .04 | −.09 | −.05 | .15 | .09 | .16 | .33** | |

| 4. | .18 | −.43*** | .74*** | .34** | −.08 | −.23* | −.23* | .18 | .00 | −.10 | −.01 | .15 | .01 | −.15 | −.08 | .02 | −.04 | −.16 | .20 | .13 | .11 | .34** | |

| 5. | .29** | −.12 | .23* | .04 | −.34** | −.55*** | −.26* | .36*** | .02 | −.21* | .16 | .12 | .19 | −.01 | .03 | −.14 | −.06 | −.06 | .09 | .54*** | .54*** | .63*** | |

| 6. | −.07 | .06 | −.14 | −.06 | −.17 | .61*** | .60*** | −.36*** | .00 | .15 | .02 | .12 | .01 | .17 | −.07 | .00 | −.03 | −.17 | −.18 | −.07 | −.22* | −.22* | |

| 7. | −.21* | .17 | −.14 | .07 | −.29** | .51** | .59** | −.48*** | .02 | .12 | .03 | −.02 | .10 | .07 | −.01 | .06 | .03 | −.05 | −.12 | −.31** | −.39*** | −.34** | |

| 8. | −.13 | .11 | −.15 | −.05 | −.19* | .77** | .56*** | −.37*** | .07 | .07 | .07 | −.07 | −.07 | .24* | .11 | −.06 | −.12 | −.10 | −.09 | −.10 | −.15 | −.27* | |

| 9. | −.08 | .00 | .10 | .13 | .18 | −.30** | −.24** | −.20* | .03 | .02 | −.00 | −.06 | .10 | −.14 | .10 | .02 | .06 | .03 | −.01 | .23* | .18 | .34** | |

| 10. | −.07 | −.06 | .10 | .22* | −.10 | −.17 | −.09 | −.17 | .14 | .62*** | −.26* | .11 | −.10 | −.25* | −.28** | −.09 | .10 | .06 | −.23* | −.12 | .00 | −.05 | |

| 11. | −.04 | −.02 | .12 | .16 | −.24** | .01 | .22* | .01 | −.09 | .54*** | −.40*** | −.15 | −.16 | −.27* | −.21 | .13 | .28** | .20 | −.44*** | −.36*** | −.21* | −.16 | |

| 12. | .22* | −.12 | −.07 | −.11 | .10 | .20* | .01 | .13 | .01 | −.33*** | −.33*** | .15 | .34** | .32** | .23* | −.12 | −.13 | −.16 | .36*** | .45*** | .15 | .16 | |

| 13. | .28** | −.05 | .17 | .05 | .21* | .07 | −.08 | .09 | −.07 | −.24** | −.25** | .41*** | .06 | −.06 | −.41*** | −.12 | .09 | .17 | .12 | .24* | .17 | .31** | |

| 14. | .19* | −.01 | .08 | .06 | .41** | −.01 | −.05 | −.07 | .03 | −.18 | −.38*** | .26*** | .32*** | .14 | .18 | −.12 | .02 | −.06 | .20 | .22* | .05 | .23* | |

| 15. | .09 | −.05 | −.09 | .03 | .05 | −.04 | −.05 | .01 | .06 | −.17 | −.15 | .35** | .17 | .07 | .39*** | −.13 | −.32** | −.14 | .37*** | .17 | .07 | −.17 | |

| 16. | .10 | −.13 | −.02 | −.06 | .14 | −.04 | −.04 | −.06 | .13 | −.34** | −.36*** | .34*** | .24* | .19* | .41*** | .08 | −.15 | −.26* | .25* | .16 | .01 | −.01 | |

| 17. | −.23* | −.08 | −.05 | −.01 | −.11 | −.14 | −.08 | −.15 | .11 | .12 | .09 | .24* | −.36*** | −.14 | −.04 | −.24* | .33** | .22* | .20 | −.30** | −.29** | −.26* | |

| 18. | −.08 | .02 | −.03 | .10 | −.12 | −.14 | .08 | −.07 | .03 | .27** | .40*** | −.36*** | −.19* | −.27** | −.33*** | −.40*** | .18 | .56*** | −.22* | −.22* | −.08 | .05 | |

| 19. | −.02 | .07 | −.12 | −.04 | −.17 | .08 | .18 | .14 | −.17 | .11 | .29** | −.29** | −.11 | −.29** | −.28** | −.32*** | .14 | .64*** | −.19 | −.12 | −.11 | −.05 | |

| 20. | .27** | −.39*** | .29** | .40*** | .11 | .10 | −.10 | .10 | .01 | −.26** | −.29** | .42*** | .31** | .24** | .34*** | .31*** | −.35*** | −.28** | −.32*** | .42** | .18 | .26* | |

| 21. | .35*** | −.09 | .14 | .06 | .54*** | −.07 | −.39*** | −.13 | .12 | −.15 | −.29** | .32*** | .39*** | .47*** | .15 | .21* | −.46*** | −.39*** | −.28** | .39*** | .45*** | .59*** | |

| 22. | .22* | −.11 | .22* | .12 | .53*** | −.01 | −.25** | −.04 | .14 | .03 | −.28** | .14 | .30** | .40*** | −.16 | −.01 | −.13 | −.12 | −.24** | .21* | .42** | .45*** | |

| 23. | .53*** | −.04 | .07 | .00 | .54*** | −.04 | .07 | −.11 | .10 | −.10 | −.19* | .29** | .36*** | .28** | −.01 | .29** | −.39*** | −.12 | −.08 | .24** | .46** | .25** |

Note. Below the diagonal, mothers; above the diagonal, fathers. 1 = Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ) History Maternal Authoritarian; 2 = PAQ History Maternal Authoritative; 3 = Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTSPC) History Physical Assault; 4 = CTSPC History Psychological; 5 = Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory Corporal Punishment Attitudes; 6 = Physical Abuse Vignettes Severity Rating; 7 = Physical Abuse Vignettes Definition; 8 = Physical Abuse Vignettes Reporting; 9 = Parent-Child Aggression Acceptability Movie Task; 10 = Video Rating Minimization; 11 = Video Rating Negative Attribution; 12 = Infant Cry Questionnaire (ICQ) Minimization; 13 = ICQ Direct Control; 14 = Plotkin Vignettes Attribution Total; 15 = Negative Mood Regulation Scale Total; 16 = Frustration Discomfort Scale Total; 17= Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task; 18 = Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) Empathic Concern; 19 = IRI Perspective Taking; 20 = Child Abuse Potential Inventory Abuse Scale; 21 = Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory; 22 = Response Analog to Child Compliance Task Intentional Noncompliance Total; 23 = PAQ Expected Authoritarian Parenting.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p < .001

The path models were estimated with and without demographic covariates of PCA risk. Preliminary analyses were used to identify worthwhile covariates in predicting PCA risk. Specifically, younger expectant mothers obtained higher CAPI Abuse Scale scores (r =− .39, p < .001), AAPI Total scores (r = −.37, p < .001) and ReACCT Noncompliance scores (r = −.34, p < .001). Similarly, younger expectant fathers also scored higher CAPI Abuse Scale scores (r = −.45, p < .001) and AAPI Total scores (r = −.35, p < .001). In addition, lower-income expectant mothers obtained higher CAPI Abuse Scale scores (r = −.44, p < 001), higher AAPI scores (r = −.33, p < .001), and ReACCT Noncompliance scores (r = −.30, p < .01). Lower-income expectant fathers also had higher scores on the CAPI Abuse scale (r = −.46, p < .001) and AAPI (r = −.49, p < .001). With respect to educational level, mothers with lower educational attainment had higher scores on the CAPI Abuse Scale (r = .48, p < .001), AAPI Total (r = −.38, p < .001), ReACCT Noncompliance (r = −.22, p < .05), as well as their predicted Authoritarian parenting style on the PAQ (r = −.23, p < .05). Fathers with lower educational levels also obtained higher CAPI Abuse Scale scores (r = −.39, p < .001), AAPI Total scores (r = −.49, p < .001), and predicted PAQ Authoritarian parenting style (r = −.27, p < .01).

Participants were classified as Minority versus Non-Minority based on their responses to race and ethnicity. Minority expectant mothers obtained significantly higher CAPI Abuse Scale scores (t (105) = −3.87, p < .001), AAPI Total scores (t (105) = −4.34, p < .001), and ReACCT Noncompliance scores (t (105) = −2.78, p < .01) than Non-Minority expectant mothers. Expectant fathers showed a similar pattern, with minority fathers obtaining significantly higher CAPI Abuse Scale scores (t (82) = −3.71, p < .001), AAPI Total scores (t (82) = −5.45, p < .001), ReACCT Noncompliance scores (t (82) = 2.75, p < .01), and predicted PAQ Authoritarian scores (t (81) = −2.29, p < .05). Based on these analyses, minority status, age, educational level, and household income were included as covariates in the path analyses. Because educational level and income were substantively collinear, and because educational level demonstrated stronger effects when entered simultaneously with the other potential covariates, income was omitted as a covariate.

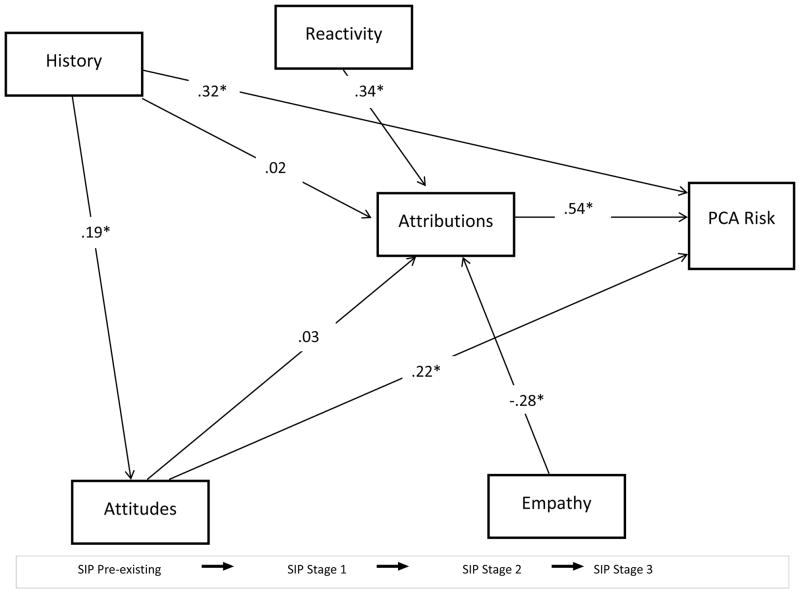

Mothers’ PCA Risk

For mothers, the SIP path model is depicted in Figure 1; the standardized coefficients are displayed. History significantly predicted attitudes (β = .19 [.01, .38], p < .05) but not attributions (β = .02 [−.14, .18], p = .801); history had a significant direct effect on PCA risk (β = .32 [.18, .47], p < .001) as well. Both attitudes (β = .22 [.10, .35], p < .001) and attributions (β = .54 [.41,.67], p < .001), in turn, significantly predicted PCA risk. Finally, as expected, reactivity (β = .34 [.12, .57], p < .01) and empathy (β = −.28 [−.49, −.08], p < .01) both significantly predicted attributions. The model R2 for PCA risk was 48.9%.

Figure 1.

SIP Path Models for Expectant Mothers (Top) and Fathers (Bottom)

Next, we estimated the three indirect effects from history to abuse risk: one from history via attitudes, one from history via attributions, and one from history via attributions and attitudes. Indirect effects were estimated using bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004), which have higher power than traditional tests of mediation (Cheung, 2007). If the indirect effect’s confidence interval excludes zero, then the indirect effect is significant. The analyses revealed that the indirect effect involving attitudes was significant (b = .04 [.00, .10]), but the indirect effects involving attributions (b = .01 [−.08, .08]) and both attitudes and attributions (b = .00 [−.02, .04]) were not. Finally, we evaluated this SIP path model using the demographic covariates for PCA risk. Including the demographic covariates, however, did not make any significant paths non-significant, and the pattern of effects was not appreciably changed. The model R2 for PCA risk did increase to 57.7%.

Fathers’ PCA Risk

For fathers, the SIP path model is depicted in Figure 1; the standardized coefficients are displayed. History significantly predicted attitudes (β = .33 [.11, .55], p < .01) but not attributions (β = .06 [−.13, .24], p = .54); history had a significant direct effect on PCA risk (β = .26 [.11, .41], p < .001) as well. Both attitudes (β = .31 [.15, .48], p < .001) and attributions (β = .42 [.28, .56], p < .001), in turn, significantly predicted PCA risk. Finally, reactivity (β = .35 [.13, .58], p < .01) significantly predicted attributions, but empathy did not (β = −.02 [−.22, .17], p = .81). In short, the fathers’ pattern of path coefficients was the same as the mothers’, with the exception of empathy, which was significant for mothers but not fathers. The model R2 for PCA risk was 44.9%.

Next, we estimated the indirect effects from history to abuse risk, using bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals. As before, the model has three indirect effects: one from history via attitudes, one from history via attributions, and one from history via attributions and attitudes. The indirect effect involving attitudes was significant (b = .11 [.03, .24]), but the indirect effects involving attributions (b = .03 [−.06, .12]) and both attitudes and attributions (b = .02 [−.01, .07]) were not. Finally, we evaluated the SIP path model using the demographic covariates for PCA risk, described earlier. As with the model for mothers, including the demographic covariates for fathers did not make any significant paths non-significant, and the pattern of effects was not appreciably changed. The model R2 for PCA risk increased to 55.1%.

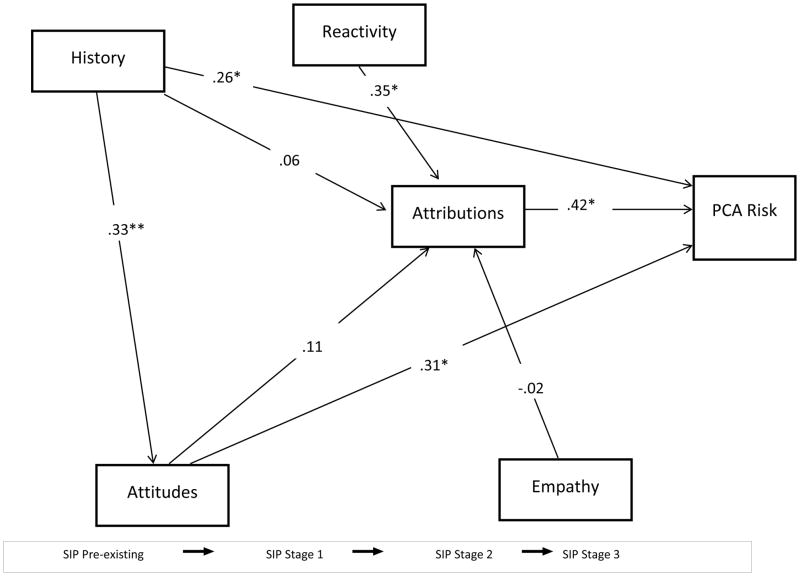

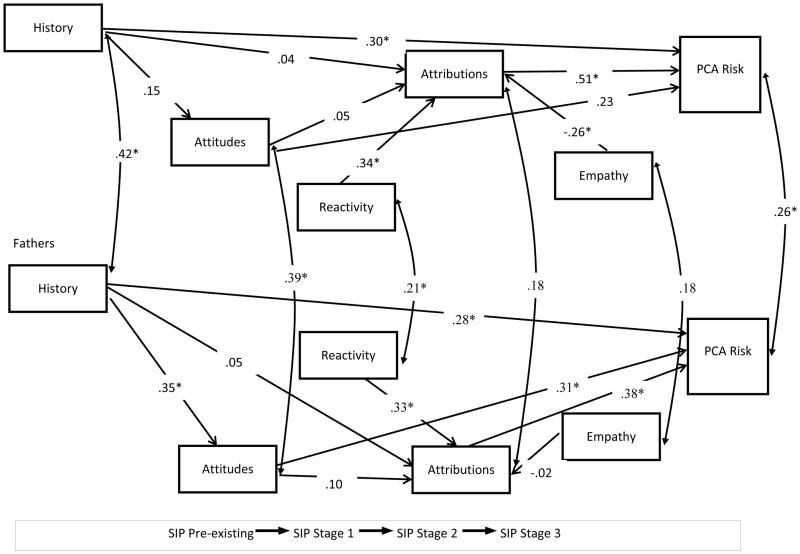

Dyadic PCA Risk

Our final model was a dyadic model that included both members of a couple in the model simultaneously. The dyadic path model thus estimates the effects for mothers and fathers in light of their nesting within the same couple and thus greater-than-chance resemblance.

Figure 2 depicts the model and its effects. The effects for mothers and for fathers were broadly similar. Regarding history’s direct paths, history only marginally predicted attitudes for mothers (β = .15 [−.03, .33], p = .11) but significantly for fathers (β = .35 [.16, .54], p < .001); history did not predict attributions for either mothers (β = .04 [−.12, .20], p > .05) or fathers (β = .05 [−.14, .23], p > .05). Finally, history had significant direct effects on abuse risk for both mothers (β = .30 [.16, .45], p < .001) and fathers (β = .28 [.13, .43], p < .001). Attitudes predicted abuse risk for both mothers (β = .23 [.09, .36], p < .001) and fathers (β = .31 [.14, .48], p < .001); attributions predicted abuse risk for mothers (β = .51 [.36, .65], p < .001) and fathers (β = .38 [.22, .54], p < .001) as well. Reactivity predicted attributions for both mothers (β = .34 [.12, .55], p < .01) and fathers (β = .33 [.09, .57], p < .01), but empathy predicted attributions for only mothers (β = −.26 [−.47, −.04], p < .05) but not fathers (β = −.02 [−.21, .18], p > .05). Overall, the joint dyadic model revealed essentially similar effects as the individual models for mothers and fathers. The model R2 for PCA risk was 45.0% for mothers and 42.7% for fathers. The one notable difference was that the mother’s effect of history on attitudes shrank in size and shifted from significant to marginal. As before, a model that included demographic covariates did not change the pattern of significant effects; the model R2 for PCA risk increased to 55.8% for mothers and 52.4% for fathers. Finally, we evaluated the indirect effects from history to abuse risk for mothers and fathers. For mothers, none of the three indirect effects—via attitudes (b = .03 [−.01, .09]), attributions (b = .02 [−.07, .10]), or both (b = .00 [−.01, .03])—was significant. For fathers, the indirect effect via attitudes was significant (b = .12 [.04, .23]), but the indirect effects via attributions (b = .02 [−.07, .11]) and both attitudes and attributions were not significant (b = .02 [−.01, .07]).

Figure 2.

Dyadic SIP Path Model Mothers

Discussion

This study utilized factors across potential stages of SIP theory to predict PCA risk in expectant mothers and fathers. Furthermore, mothers’ and fathers’ personal history of abusive and harsh parenting was hypothesized to indirectly affect their PCA risk through SIP components of approval of PCA and negative child attributions. SIP components were applied to a mother model, a father model, and a dyadic model, with results providing support for major elements of the SIP theory across models.

Interestingly, mother and father PCA risk models did not markedly differ. Both PCA risk models demonstrate that experiencing more PCA during childhood fosters parents’ approval of PCA yet still directly accounted for increased PCA risk; however, their personal history did not appear to shape the development of negative child attributions to indirectly contribute to PCA risk. When the dyadic PCA risk model was examined, history was notably stronger in predicting PCA attitudes for fathers than mothers. Childhood experiences of PCA affects the development of parents’ cognitions (Kolko et al., 2002), leading the parent to accept familiar harsh parenting practices (Rodriguez & Sutherland, 1999). The observation that personal history was more influential in PCA acceptance for fathers is intriguing and worth pursuing in future research given that others have speculated about the role of historical variables in abuse risk among fathers (Guterman & Lee, 2005), but such indirect influences also need clarification for mothers. Additionally, the finding that history did not influence negative attributions for either parent offers preliminary evidence that this may not be one of the mechanisms whereby personal history elevates risk.

For SIP Stage 1, reactivity was observed to influence negative attributions for both expectant parents. Parents who easily overreact and become frustrated may be more prone to aggression, and indeed, such qualities have been observed to escalate abuse risk (e.g., Stith et al., 2009). SIP Stage 2 follows a similar pattern wherein, for both mothers and fathers, negative child attributions were predictive of PCA risk, also observed in the dyadic PCA risk model. Research has previously noted the importance of negative attributions among at-risk and abusive parents (e.g., Berlin et al., 2013; Haskett et al., 2006). However, Stage 3 introduces another difference between mothers and fathers. For mothers, lower empathy related to negative child attributions, but this effect was not observed for fathers. In contrast, one small sample found empathic perspective-taking was compromised for high-risk fathers but not mothers (Perez-Albeniz & De Paul, 2004). Because empathy can reduce aggression (Richardson et al., 1994), whether mothers and fathers in fact display empathy differentially should be considered further, particularly because this suggests that enhancing empathy might not be able to alter father’s attributions.

Overall, the SIP model worked fairly well for both mothers and fathers, but some factors seem to carry more weight for mothers versus fathers, such as empathy relating to attributions for mothers only and father’s personal history more clearly predicting negative PCA attitudes. Our findings parallel speculations in the literature that fathers and mothers demonstrate similar risk profiles (e.g., Schaeffer et al., 2005; Smith Slep & O’Leary, 2007), which could be directly compared in our study. Future studies should continue such research with fathers, identifying other factors that could differentially contribute to fathers’ PCA risk, such as qualities of the partner relationship or psychopathology.

Several strengths and limitations are apparent in this study. First, the inclusion of fathers adds to the literature, including direct comparisons between mothers and fathers, and second, the mulitmethod approach provides a more comprehensive assessment of critical variables to reduce biases. Testing multiple components of the SIP model simultaneously is also relatively rare, particularly while also considering the role of personal history. However, the current study findings are based on a cross-sectional design, similar to models that have considered multiple components simultaneously (e.g., Smith Slep & O’Leary, 2007). Thus, the current models permit a consideration of how these variables are interconnected, but not causally linked. This study also involved expectant parents who are not yet parenting. To better appreciate the development of PCA risk and how influential factors predict changes over time, a longitudinal design is warranted, which the Triple-F study aims to perform. Additionally, larger samples would facilitate more sophistication using SEM analyses. Other risk factors that may reflect different ecological predictors of PCA (e.g., social support, neighborhood characteristics, cultural norms) could also be incorporated in future research to enrich the picture of what shapes parents’ propensity to maltreat children. The demographic finding that income was displaced by educational attainment would be interesting to replicate with a larger sample that could incorporate other ecological variables. Finally, although some of the analog measures are fairly ambiguous in their intent, they were presented in tandem with the explicit self-report measures, which may have diminished their implicit nature.

Collectively, the current findings provide promising support for a cognitive approach to how parents’ decision making may culminate in PCA. Cognitive-behavioral approaches could be applied to components in such theoretical models. For example, given the current findings, helping parents adjust their PCA acceptance and modify their negative attribution biases toward children could prove a fruitful approach to abate the risk for physical child maltreatment. For example, an enhanced home-visiting prevention program has included shifting attributions of children’s control and negative intent to reduce physical child abuse (Bugental et al., 2002). Likewise, parents could receive training in augmenting their frustration tolerance, decreasing their reactivity to negative events. Such efforts to enhance frustration tolerance have long been incorporated into cognitive-behavioral strategies such as Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (Harrington, 2011). Rehearsing such cognitive-behavioral strategies might encourage parents to become more aware of some of the cognitions they access during discipline encounters, perhaps by incorporating some of these SIP elements into such interventions as the Nurturing Parenting Program (Bavolek, 2000). Thus, given the current findings, more explicitly integrating some of these SIP elements to enrich home-visiting programs in an effort to address some of the modest or mixed success currently observed in those approaches (Green, Tarte, Harrison, Nygren, & Sanders, 2014). Whether some of the cognitive adjustments could be achieved with media campaigns remains an interesting, non-traditional venue for public policy efforts with wider audiences (e.g., Barlow & Calam, 2011). In sum, research using such theoretically-grounded approaches is imperative in delineating important targets in prevention and intervention efforts. These findings reinforce that cognitive processes are significant components related to PCA that should be considered in such programs.

Acknowledgments

We thank our participating families and participating Obstetrics/Gynecology clinics that facilitated recruitment. This research was supported by award number R15HD071431 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Christina M. Rodriguez, University of Alabama at Birmingham

Tamika L. Smith, University of Alabama at Birmingham

Paul J. Silvia, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

References

- Ateah CA, Durrant JE. Maternal use of physical punishment in response to child misbehavior: Implications for child abuse prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:169–185. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Calam R. A public health approach to safeguarding in the 21st century. Child Abuse Review. 2011;20:238–255. [Google Scholar]

- Bavolek SJ. The Nurturing Parenting Programs. 2000 Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/html/ojjdp/2000_11_1/contents.html.

- Bavolek SJ, Keene RG. Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory (AAPI-2): Administration and Development Handbook. Park City, UT: Family Development Resources, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development. 2011;82:162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Reznick JS. Examining pregnant women’s hostile attributions about infants as a predictor of offspring maltreatment. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:549–553. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower-Russa M. Attitudes Mediate the Association Between Childhood Disciplinary History and Disciplinary Responses. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:272–282. doi: 10.1177/1077559505277531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster AL, Nelson JP, Hymel KP, Colby DR, Lucas DR, McCanne TR, Milner JS. Victim, perpetrator, family, and incident characteristics of 32 infant maltreatment deaths in the United States Air Force. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:91–101. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Ellerson PC, Lin EK, Rainey B, Kokotovic A, O’Hara N. A cognitive approach to child abuse prevention. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:243–258. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buri JR. Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Assessment. 1991;57:110–119. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro SJ, Mearns J. Measuring generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation: Initial scale development and implications. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;54:546–563. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerny JE, Inouye J. Utilizing the child abuse inventory in a community health nursing prevention program for child abuse. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2001;18:199–211. doi: 10.1207/S15327655JCHN1804_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung MWL. Comparison of approaches to constructing confidence intervals for mediating effects using structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:227–246. [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Mathew L, Rothkopf AC, Elo IT, Coyne JC, Culhane JF. Parenting attitudes and infant spanking: The influence of childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2009;124:278–286. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig CD, Sprang G. Trauma exposure and child abuse potential: Investigating the cycle of violence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:296–305. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis GC. Does violence breed violence-Perhaps? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1963;120:386–387. doi: 10.1176/ajp.120.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology. 1980;10:85. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. The effects of dispositional empathy on emotional reactions and helping: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality. 1983;51:167–184. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Reid JB, Knutson JF. Direct laboratory observations and analog measures in research definitions of child maltreatment. In: Feerick M, Knutson JF, Trickett P, Flanzier S, editors. Child abuse and neglect: Definitions, classifications, and a framework for research. Baltimore, MD: Brooks; 2006. pp. 293–328. [Google Scholar]

- Dollard J, Doob L, Miller N, Mowrer O, Sears R. Frustration and aggression. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SJ, Tonican JS. Trauma and intravenous drug use among pregnant alcohol/other drug abusing women: Factors in predicting child abuse potential. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2008;26:313–332. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH, Olson MA. Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and use. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:297–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Tarte JM, Harrison PM, Nygren M, Sanders MB. Results from a randomized trial of the Health Families Oregon accredited statewide program: Early program impacts on parenting. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;44:288–298. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald RL, Bank L, Reid JB, Knutson JF. A discipline-mediated model of excessively punitive parenting. Aggressive Behavior. 1997;23:259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Guterman NB, Lee Y. The role of fathers in risk for physical child abuse and neglect: Possible pathways and unanswered questions. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:136–149. doi: 10.1177/1077559505274623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltigan JD, Leerkes EL, Burney RV, O’Brien M, Supple AJ, Calkins SD. The infant crying questionnaire: Initial factor structure and validation. Infant Behavior and Development. 2012;35:876–883. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington N. The Frustration Discomfort Scale: Development and psychometric properties. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2005;12:374–387. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington N. Frustration Intolerance: Therapy issues and strategies. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2011;29:4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Haskett ME, Johnson CA, Miller JW. Individual differences in risk of child abuse by adolescent mothers: Assessment in the perinatal period. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1994;35:461–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskett ME, Scott SS, Fann KD. Child Abuse Potential Inventory and parenting behavior: Relationships with high-risk correlates. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19:1483–1495. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskett ME, Scott SS, Willoughby M, Ahern L, Nears K. The Parent Opinion Questionnaire and child vignettes for use with abusive parents: Assessment of psychometric properties. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21:137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, Knight ED, Lau AS, Dubowitz H, Kotch JB. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: Distinction without a difference? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin LM, Skowronsi JJ, Crouch JL, Milner JS, Zengel B. Reactions to children’s transgressions in at-risk caregivers: Does mitigating information, type of transgression, or caregiver directive matter? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38:917–927. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Deakin University; Australia: 2006. Child-related information processing in step-parents: Investigating the Cinderella effect. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Zigler E. Do abused children become abusive parents? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:186–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Brown EJ, Berliner L. Children’s perceptions of their abusive experience: Measurement and preliminary findings. Child Maltreatment. 2002;7:42–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Grogan-Kaylor A, Berger LM. Parental spanking of 1-year-old children and subsequent child protective services involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38:875–883. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Kim J, Taylor CA, Perron BE. Profiles of disciplinary behaviors among biological fathers. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16:51–62. doi: 10.1177/1077559510385841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EL, Siepak K. Attachment linked predictors of women’s emotional and cognitive responses to infant distress. Attachment & Human Development. 2006;8:11–32. doi: 10.1080/14616730600594450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, Medina AM, Oliver PH. The co-occurrence of husband-to-wife aggression, family-of-origin aggression, and child abuse potential in a community sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:413–440. [Google Scholar]

- McElroy EM, Rodriguez CM. Mothers of children with externalizing behavior problems: Cognitive risk factors for abuse potential and discipline style and practices. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:774–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennen FE, Trickett PK. Parenting attitudes, family environments, depression, and anxiety in caregivers of maltreated children. Family Relations. 2011;60:259–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS. The Child Abuse Potential Inventory: Manual. 2. Webster, NC: Psyctec; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS. Social information processing and physical child abuse. Clinical Psychology Review. 1993;13:275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS. Assessing physical child abuse risk: The Child Abuse Potential Inventory. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14:547–583. [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS. Social information processing and child physical abuse: Theory and research. In: Hansen DJ, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation, Vo. 46, 1998: Motivation and child maltreatment. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2000. pp. 39–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS, Dopke C. Child physical abuse: Review of offender characteristics. In: Wolfe DA, McMahon RJ, Peters RD, editors. Child Abuse: New directions in prevention and treatment across the lifespan. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Montes MP, de Paul J, Milner JS. Evaluations, attributions, affect, and disciplinary choices in mothers at high and low risk for child physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1015–1036. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DR, Florsheim P. Interpartner conflict and child abuse risk among African American and Latino adolescent parenting couples. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Albeniz A, De Paul J. Gender differences in empathy in parents at high- and low-risk of child physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peugh JL, DiLillo D, Panuzio J. Analyzing mixed-dyadic data using structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2013;20:314–337. [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin R. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Rochester; 1983. Cognitive mediation in disciplinary actions among mothers who have abused or neglected their children: Dispositional and environmental factors. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D, Hammock G, Smith S, Gardner W, Signo M. Empathy as a cognitive inhibitor of interpersonal aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 1994;20:275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Robyn S, Fremouw WJ. Cognitive and affective styles of parents who physically abuse their children. American Journal of Forensic Psychology. 1996;14:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM. Parent-child aggression: Association with child abuse potential and parenting styles. Violence and Victims. 2010a;25:728–741. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM. Personal contextual characteristics and cognitions: Predicting child abuse potential and disciplinary style. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010b;25:315–335. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Bower-Russa M, Harmon N. Assessing abuse risk beyond self-report: Analog task of acceptability of parent-child aggression. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Richardson MJ. Stress and anger as contextual factors and pre-existing cognitive schemas: Predicting parental child maltreatment risk. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:325–337. doi: 10.1177/1077559507305993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CM, Sutherland D. Predictors of parents’ physical disciplinary practices. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:651–657. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer CM, Alexander PC, Bethke K, Kretz LS. Predictors of child abuse potential among military parents: comparing mothers and fathers. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20:123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Schloss HM, Haaga DAF. Interrelating behavioral measures of distress tolerance with self-reported experiential avoidance. Journal of Rational-Emotive Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. 2011;29:53–63. doi: 10.1007/s10942-011-0127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, Li S. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, Executive Summary. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/nis4_report_congress_full_pdf_jan2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Shanalingigwa OA. Doctoral dissertation. University of Minnesota; 2009. Understanding social and cultural differences in perceiving child maltreatment. Dissertation Abstracts International. [Google Scholar]

- Sidebotham P, Golding J The ALSPAC Study Team. Child maltreatment in the “Children of the Nineties”: A longitudinal study of parental risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1177–1200. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Slep AM, O’Leary SG. Multivariate models of mothers’ and fathers’ aggression toward their children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:739–751. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Liu T, Davies C, Boykin EL, Alder MC, Harris JM, Dees JEMEG. Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. New evidence for the benefits of never spanking. Society. 2001;38:52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Ordinary violence, child abuse, and wife beating: What do they have in common? In: Finkelhor D, Gelles RJ, Hotaling GT, Straus MA, editors. The dark side of families: Current family violence research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1983. pp. 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Lee SJ, Guterman NB, Rice JC. Use of spanking for 3-year-old children and associated intimate partner aggression or violence. Pediatrics. 2010;126:415–424. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Child Maltreatment 2013. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2013.

- Wendorf CA. Comparisons of structural equation modeling and hierarchical linear modeling approaches to couples’ data. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Whipple EE, Richey CA. Crossing the line from physical discipline to child abuse: How much is too much? Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;5:431–444. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Does Violence Beget Violence? Psychological Bulletin. 1989;106:3–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotor AJ, Theodore AD, Chang JJ, Berkoff MC, Runyan DK. Speak softly—and forget the stick: Corporal punishment and child physical abuse. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2008;35:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]