Abstract

Various hypertensive stimuli lead to exuberant adventitial collagen deposition in large arteries, exacerbating blood pressure elevation and end-organ damage. Collagen production is generally attributed to resident fibroblasts, however other cells, including resident and bone marrow derived Stem Cell Antigen positive (Sca1+) cells, endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, can produce collagen and contribute to vascular stiffening. Using flow cytometry and immunofluorescence, we found that adventitial Sca-1+ progenitor cells begin to produce collagen and acquire a fibroblast-like phenotype in hypertension. We also found that bone marrow derived cells represent more than half of the matrix producing cells in hypertension, and that one-third of these are Sca-1+. Cell sorting and lineage tracing studies showed that cells of endothelial origin contribute to no more than one-fourth of adventitial collagen I+ cells while those of vascular smooth muscle lineage do not contribute. Our findings indicate that Sca-1+ progenitor cells and bone marrow-derived infiltrating fibrocytes are major sources of arterial fibrosis in hypertension. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition likely also contributes, albeit to a lesser extent and pre-existing resident fibroblasts represent a minority of aortic collagen-producing cells in hypertension. This study shows that vascular stiffening represents a complex process involving recruitment and transformation of multiple cells types that ultimately elaborate adventitial extracellular matrix.

Keywords: Sca-1+ progenitors, endothelial to mesenchymal transition, circulating fibrocytes, Masson’s stain, adventitia and collagen deposition

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension induces a striking deposition of collagen in the aortic adventitia. This fibrotic process results in loss of the “Windkessel function” of the proximal aorta and worsens systolic hypertension and target organ damage. Increased pulse wave velocity, which reflects aortic stiffening, is associated with higher cardiovascular risk.1 Recently pulse forward wave amplitude, which likewise reflects aortic stiffness, was also found to associated with elevated risk of cardiovascular events.2

Resident fibroblasts have been traditionally been thought to be a major source of tissue fibrosis in wound healing, atherosclerosis and vascular fibrosis. We have previously shown that T cell cytokine IL-17A and increased mechanical stretch, which are commonly encountered in hypertension, drive expression of multiple collagen subtypes in primary mouse aortic fibroblasts. This is mediated by activation of the p38 MAP kinase and inhibition of this enzyme prevents collagen deposition both in vitro and in vivo.3 Hypertensive stimuli such as reactive oxygen species also activate fibroblasts, promoting fibrogenesis and tissue remodeling.4, 5

Stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1, alternatively known as lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus A or Ly-6A) positive progenitor cells reside in the vascular adventitia which is a major site of collagen deposition in hypertension.3, 6 These pluripotent cells emerge during embryogenesis, persist into adulthood and represent roughly 20% of aortic adventitial cells.7, 8 In mouse aortas, they express several hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) markers, including Lin, c-kit and CD34.9, 10 Sca-1 cells are maintained by sonic hedgehog signaling (Shh) in the aortic adventitia, and in Shh−/− mice these cells are either absent or diminished in number.7 In healthy arteries of adult mice, Sca-1+ progenitors maintain endothelial and smooth muscles cells and generate vascular-like branching structures when cultured on matrigel.10 However, under disease conditions such as atherosclerosis and vascular injury, these cells have the capacity to differentiate into mesenchymal phenotype and might contribute to tissue fibrosis.8

Circulating fibrocytes are considered a specialized population of leukocytes that express collagen I and CD45.11–14 These cells migrate to inflamed or injured tissues via chemotactic ligand-receptor interactions, and have been shown to play a role in wound healing and fibrosis of the heart, lung and kidney.11–14 Once recruited to sites of inflammation, fibrocytes secrete additional chemokines that attract more fibrocytes and other leukocytes, including T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells.11, 15, 16 Fibrocytes also promote tissue remodeling by depositing fibrotic proteins including collagen. In addition, by secreting TGF-beta1, they may also induce transformation of endothelial cells to a fibroblast-like phenotype, a phenomenon known as endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EndoMT).11, 17

Thus, collagen-forming cells of the vessel can include resident fibroblasts, endothelial to mesenchymal transition, Sca-1 cells and recruitment of circulating fibrocytes. It is unclear however whether and how these different populations are involved the pathogenesis of aortic stiffening in hypertension. In the present study, we found that adventitial Sca-1+ progenitor cells acquire a collagen I-producing phenotype in hypertension, potentially contributing to collagen deposition and aortic stiffening. We also found that bone marrow-derived collagen I+CD45+ circulating fibrocytes infiltrate the large vessels and further promote arterial fibrosis in hypertension. These findings provide a new paradigm to support the roles of vascular and bone marrow origins of fibroblasts in response to vascular injury and inflammation.

METHODS

Animals

C57Bl/6, tgLy-6A/EGFP and tgCAG-EGFP male mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories at 12 weeks of age. Tie1-cre×ROSA26-STOPfl/fl-EYFP mice and tgmyh11-cre×ROSA26-STOPfl/fl-EYFP mice received with tamoxifen injections at 8 weeks of age and were used for lineage tracing studies at 12 weeks of age as previously described.18, 19 Hypertension was induced by infusion of angiotensin II (490 ng/kg/min) via osmotic minipumps for two weeks. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Vanderbilt approved all experimental protocols.

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT)

Two weeks prior to BMT, 12 week old WT mice were transferred to sterile cages and fed sterile chow and acidified water (pH 2.0) containing 1 mg/ml of sulfamethazine-Na+ (Sigma) and 0.2 mg/ml of trimethoprim (Sigma) for prophylaxis. On the day of BMT, mice were lethally irradiated with a dose of 10 Gy 4 hrs prior to BMT via a 137Cs irradiator (J. L. Shepherd and Associates, Glendale, CA). Bone marrow cells (2 × 107 cells) were obtained from femurs and tibias of tgCAG-EGFP mouse mice and were injected by the tail vein into recipient mice. The mice were then housed for 6 weeks to allow engraftment of the bone marrow. Successful engraftment was confirmed upon sacrifice by flow cytometry of peripheral blood mononuclear cells for EGFP expression.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared from aortas as previously described.3, 20 Briefly, the entire aorta with surrounding perivascular fat was minced with fine scissors and digested with 1 mg/mL collagenase A, 1 mg/ml collagenase B, and 100 µg/ml DNase I in phenol-free RPMI 1640 medium with 5% FBS for 30 min at 37°C, with intermittent agitation. Fc receptors were blocked with anti-mouse CD16/CD32 for 20 min at 4°C (BD Biosciences, clone 2.4G2) prior to the staining of surface markers. The antibodies used were: PerCP-Cy5 anti-CD45; PE anti-CD34; APC anti-CD34, APC-Cy7 anti-Sca-1/Ly-6A; PE-Cy7 anti-c-kit/CD117; Amcyan anti-CD31. All aortic cells were incubated with 1.5 µl of each antibody in 100 µl of FACS buffer for 35 minutes. The cells were then washed twice with FACS buffer and immediately analyzed on a FACSCanto flow cytometer with DIVA software (Becton Dickinson). Dead cells were excluded from analysis with a fixable Violet dead cell stain. Intracellular staining was then performed with the Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Plus fixation/permeabilization solution kit (BD Biosciences) using a mouse monoclonal antibody (Abcam) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or 647 (Molecular Probes). For each experiment, we performed flow minus one (FMO) controls for each fluorophore to establish gates. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence

Aortic collagen was visualized by Masson’s trichrome staining as previously described.3 Immunofluorescence staining was performed on fix-perfused mouse aortas embedded in OCT. Six micron sections were sliced in a serial sequence. Samples were permeabilized with Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). Antigen blocking was performed with 10% donkey serum (Abcam) prior to incubation with primary antibodies. These include monoclonal rat anti-Sca-1, monoclonal mouse anti-collagen I, polyclonal rabbit anti-collagen III, poly clonal rabbit anti-collagen V, polyclonal goat anti-EGFP, polyclonal goat anti-GFP and rabbit anti-Fsp-1 antibodies. Donkey polyclonal antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, 555 or 647 were used for binding 1st antibodies. DAPI (Invitrogen) was added in the last wash following incubation with secondary antibodies. All slides were mounted with Prolong Anti-fade media (Life Technologies). Isotype and no antibody controls for collagen I staining revealed no immunofluorescence (Figure S1A).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Student’s t tests were used to compare the effects of sham and angiotensin II. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the effect of angiotensin II infusion on the gene expression of aortic cells as well as the density of circulating fibrocytes followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test when significance was indicated. P values are reported in the figures.

RESULTS

Multiple cell types produce collagen in hypertension

To identify cell types that produce matrix proteins, we employed cell sorting as shown in Figure 1A and examined mRNA levels for collagen 1a1, 3a1 and 5a1 and fibronectin-1. Chronic angiotensin II infusion increased collagen mRNAs by 2-fold and fibronectin-1 mRNA by 4-fold in CD31+ cells (Figure 1B–E). Of note, the increases in mRNA for collagen subtypes were even greater in CD31−Sca-1+ cells and in CD31−Sca-1− cells.

Figure 1.

Subsets of aortic cells that express matrix protein mRNAs in hypertension. A) CD31+, CD31−Sca-1+ and CD31−Sca-1− cells were isolated using magnetic-activated cell sorting. B–E) Real-time PCR analysis of expression of collagen 1a1, 3a1, 5a1 and fibronectin-1 in cells fractions isolated from the aorta of sham and angiotensin II-treated mice (n=6).

To confirm our PCR results and to further examine cells that produce collagen, we employed multicolor flow cytometry on single cell suspensions of the aorta. We found that hypertension induced a 2.6-fold increase of aortic CD31−Sca1+ progenitor cells (Figure 2A, 2B and 2F) compared to sham-infused mice. The number of these CD31−Sca1+ cells that produced collagen I more than doubled in response to angiotensin II (Figure 2E and 2G). Of note, a majority of CD31+ cells were Sca-1+. In keeping with the PCR results, angiotensin II infusion also increased aortic CD31+Col I+ cells, although the absolute number of these cells was small compared the Sca-1+Col I+ cells (Figure 2C and 2H). CD31−Sca-1−Col I+ cells were also increased in the aortas of angiotensin II-infused mice (Figure 2D and 2I).

Figure 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of aortic collagen producing cells. Mice received angiotensin II or sham treatment for 14 days and flow cytometry was performed on single cells suspensions of the aorta. Panel A shows the gating strategy employed. Panels B–E show subsets of vascular cells that stain positively for intracellular collagen. Mean data are shown in panels F–I. Comparisons were made with Student’s t test (n=6–8).

Role of Sca-1 positive cells in aortic fibrosis

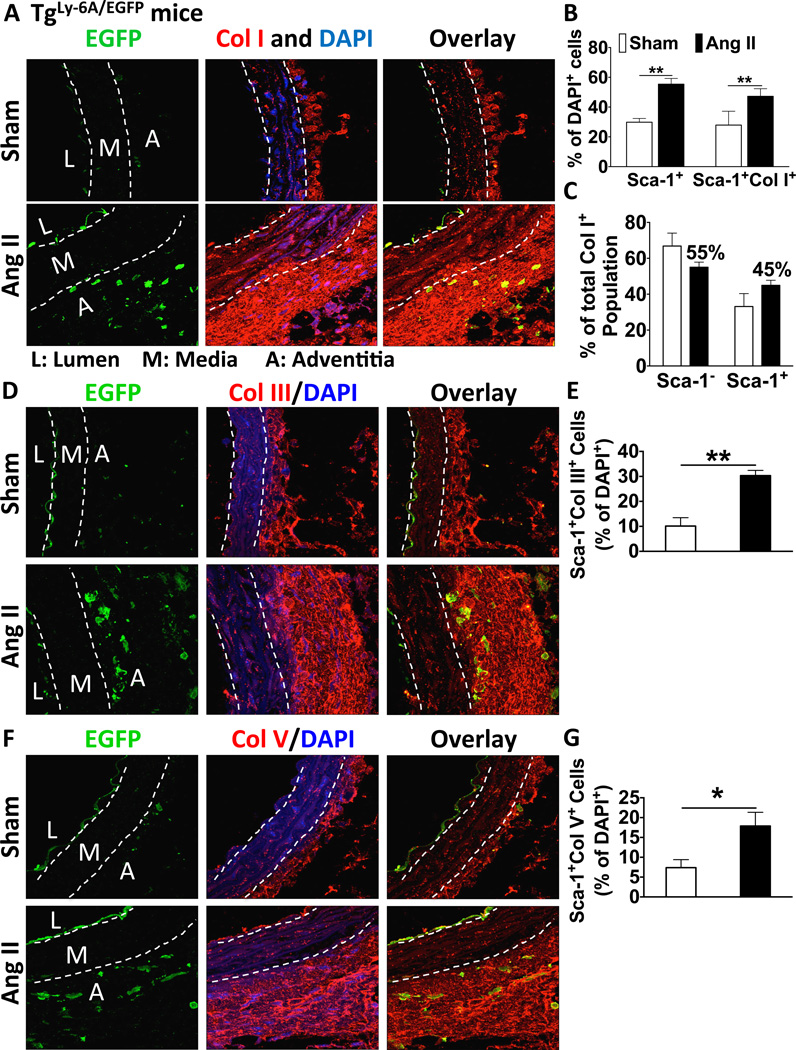

To confirm the participation of Sca-1+ cells in aortic fibrosis we studied transgenic mice expressing a Sca-1-EGFP construct (tgLy-6A/EGFP). These animals developed collagen deposition identical to that observed in wild-type mice in response to angiotensin II infusion (Figure S1B). In addition angiotensin II increased EGFP+ cells in the aortic adventitia (Figure 3A–B). Of note, these cells were closely associated with the region of adventitial collagen deposition and some of them also contained collagen I, as indicated by yellow co-localization. The number of Sca-1+Col I+ cells was increased 2-fold with hypertension and represented 45% of total adventitial collagen I+ cells (Figure 3B–C). Of note, collagen III and V were also deposited in the adventitia and co-localized with EGFP+ cells (Figure 3D–G).

Figure 3.

The role of Sca-1+ cells in adventitial collagen deposition. TgLy-6A/EGFP mice received angiotensin II or sham treatment for 14 days. Frozen sections of mouse aortas were used for staining. A–C) Immunofluorescence showing co-localization of Sca-1 driven EGFP and collagen I in the aorta adventitia (n=6). D–G) Immunofluorescence showing co-localization of Sca-1 driven EGFP and collagen III and V in the aorta adventitia (n=6). Data in panels B, E and G represent percentages of DAPI+ cells.

Role of endothelial and smooth muscle lineage cells in aortic fibrosis

To examine the possibility that Sca-1+Col I+ cells are of endothelial origin, we employed Tie1-cre × Rosa26-STOPfl/fl-EYFP mice for lineage tracing studies. Angiotensin II infusion raised blood pressure to a similar extent in these animals as in wild-type mice (Figure S2A and S2B). The degree of collagen deposition caused by angiotensin II, as detected by Masson’s Trichrome staining was also similar in these mice as to that observed in wild-type mice (Figure S2C). In addition angiotensin II increased EYFP+/collagen+ cells as detected by immunofluorescence (Figure 4A and B, and Figure S3). This analysis revealed that 24% of total collagen I+ cells in the adventitia were positive for EYFP+ (Figure 4C). Co-staining revealed that 20% of adventitial Sca-1+ cells were also positive for this endothelial lineage tracer (Figure 4A and B). Using flow cytometry, we confirmed that about 1/5th of collagen I+ cells were EYFP+ (Figure S4C and S4D). While Tie1 is expressed in endothelial cells, some bone marrow-derived cells also express this marker. Thus, at most, only about one-fourth of collagen I-producing cells are of endothelial lineage.

Figure 4.

The roles of cells derived from endothelial lineage or smooth muscle cell lineages. A–C) Lineage tracing studies using Tie1-cre × ROSA26-STOPfl/fl-EYFP mice to identify cells of endothelial origin that produce collagen I (n=6). D–E) Lineage tracing using tgmyh11-cre × ROSA26-STOPfl/fl-EYFP mice showing absence of collagen I producing cells of smooth muscle origin. Cre−/− × ROSA26-STOPfl/fl-EYFP littermates served as a negative control of EYFP expression.

We also examined the role of smooth muscle lineage cells in collagen deposition. In both sham and angiotensin II-infused tgmyh11-cre × Rosa26-STOPfl/fl-EYFP mice, smooth muscle lineage cells were primarily identified between the elastic laminae layers of the media, not in the adventitia (Figure 4D–E) and did not co-localize with collagen positive cells. Moreover, smooth muscle cells did not appear to significantly contribute to adventitial Sca-1+ cells (Figure S5).

Role of bone marrow-derived cells in aortic fibrosis

We performed bone marrow transplantation of EGFP+ cells into wild-type mice and subsequently subjected these mice to sham or angiotensin II infusion (Figures S6A and S6B). Bone marrow recipients developed a similar degree of aortic collagen deposition in response to angiotensin II infusion (Figure S6C). Of note, angiotensin II infusion also raised blood pressure in these animals to the same degree as observed in wild-type mice (Figures S7A and S7B). Preliminary studies identified EGFP+/Collagen I+ cells in the circulation, but angiotensin II infusion did not affect the prevalence of these (data not shown). Few bone marrow-derived cells were present in the adventitia of sham-treated mice (Figure 5A and B); however, hypertension caused a 2-fold increase of EGFP+ cells in the aortic adventitia. The number of cells positive for both EGFP and the fibroblast marker Fsp-1 was increased by 4-fold by angiotensin II infusion (Figure S8), indicating that many fibroblast-like cells are bone marrow-derived. In sham mice, only 10% of EGFP+ cells were Fsp-1+, but this fraction increased 4-fold in hypertensive mice (Figure 5C), suggesting differentiation of these cells into a fibroblast phenotype. These EGFP+ cells were predominantly found in the adventitia and almost one-half co-localized with collagen I (Figure 5C). These cells also co-localized with collagen III, but not with collagen V (Figure S9).

Figure 5.

Role of bone marrow derived cells in vascular fibrosis and summary. Mice underwent bone marrow transplant with EGFP+ cells and subsequently received sham or angiotensin II infusion. A–C) Co-localization of bone marrow derived cells with collagen and Fsp-1+ cells. D–I) Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow derived cells in the aorta that produce collagen and express Sca-1. Gating strategy is shown in panel D.

To further quantify the contribution of bone marrow-derived cells, we performed flow cytometry of vessels from these bone marrow chimeric mice (Figure 5D). In angiotensin II-infused mice, 62% of collagen I-producing cells were EGFP positive while 38% were EGFP negative (Figure 5E–F and I). EGFP+ cells were almost all CD45+Col I+ and were more than doubled in hypertension.

Sca-1+ cells can exist as vascular resident progenitor cells, or can arise from the bone marrow, and the bone marrow may serve as a repository for tissue resident Sca-1+ cells. We found in sham infused mice that 16% of the aortic Sca-1+ cells were EGFP+ and thus were derived from the bone marrow. Importantly, hypertension tripled this contribution of bone marrow-derived Sca-1+ cells (Figure 5G–H). Thus, a majority of collagen I-producing cells in the aortic adventitia in hypertension are either bone-marrow derived or are Sca-1+, and at least half of the latter are also bone marrow-derived.

DISCUSSION

The present study reveals three previously unidentified cell types as sources of vascular fibrosis in hypertension. These include resident Sca-1+ cells, bone marrow-derived cells and to a lesser extent, cells of endothelial origin. As illustrated in Figure 6A and 6B, bone marrow-derived cells and Sca-1+ cells account for the majority of collagen producing cells of the aorta in hypertension. In addition, 24% of the collagen-producing cells were of Tie1-lineage. Given that some bone marrow-derived cells can also express Tie1, this indicates that EndoMT accounts at most for only about one-fourth of collagen producing cells. By exclusion, our data indicate that pre-differentiated resident fibroblasts represent only a small fraction of the vascular-fibrosing cells in hypertension. Aortic stiffening is thus a highly dynamic process involving differentiation of resident Sca-1+ cells, recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells and to a lesser extent EndoMT and resident fibroblasts.

Figure 6.

Working hypothesis showing the contributions of Sca-1+ progenitors, bone marrow derived and cells of endothelial origin in aortic collagen deposition. The Venn diagram shows the relative contributions of various sources of collagen I-producing cells in the bone marrow chimeric mice.

Sca-1 is expressed in all embryonic and adult mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Sca-1+c-kit+CD41+ hematopoietic cells first emerge from the endothelium of the dorsal aorta at embryonic day 10.5.21 Adventitial Sca-1+ cells appear in the perivascular space between the ascending aorta and the pulmonary trunk between E15.5 and E18.5 and persist in this position until after birth.7 As adventitial Sca-1+ cells emerge well after development of the tunica media, they likely represent embryonic hematopoietic stem cells that have arrived by the vasa vasorum. These cells remain in the vascular adventitia thereafter and expand in number during postnatal growth. These Sca1+ cells are known to give rise to other vascular cells, including vascular smooth muscle cells and can contribute to pathological processes including atherosclerosis and perivascular cardiac fibrosis in Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy.7, 8, 22 Our current findings show that Sca-1+ cells in the adult can also give rise to collagen-producing cells and contribute to vascular fibrosis in hypertension.

We also found that more than half of collagen I-producing cells of the aorta are bone marrow-derived, and some of these are Sca-1+. This is in keeping with the concept that CD45+Col I+ bone marrow-derived fibrocytes circulate and can be recruited to areas of inflammation via chemoattractant signals such as the CCL-21/CCR7 axis.11 We found such fibrocyte-like cells in the blood of mice, but their prevalence was unaffected by angiotensin II infusion. A similar role of circulating fibrocytes has been identified in pulmonary and cardiac fibrosis.23

Inflammatory molecules associated with hypertension, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-1β, can promote EndoMT by suppressing expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR), an inhibitor of TGF-β/TGF-βR1 signaling.24 While immune cells that produce these cytokines accumulate in the adventitia in hypertension, we found that a minority of collagen producing cells is of endothelial origin. This was established by showing that CD31+ cells in the aorta of hypertensive mice express much less mRNA for collagen 1a1, 3a1, 5a1 and fibronectin-1 than did CD31− cells. Moreover, only about one fourth of collagen producing cells is of endothelial origin as estimated by Tie1 lineage tracing.

Perspectives

The present studies show that aortic fibrosis is a highly dynamic process involving transformation and recruitment at least three sources of matrix-producing cells. These studies refute the traditional concept that adventitial fibrosis is solely caused by activation of pre-existing fibroblasts in the aorta. Moreover, our studies emphasize the complexity of the vascular adventitia and its capacity to respond to a pathological stimulus such as hypertension. Prevention of vascular stiffening will likely require interventions that target each of these sources of fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What is new?

We demonstrate that at least 3 sources of cells contribute to aortic adventitial collagen deposition in hypertension. These include Sca-1+ cells, bone marrow-derived cells and transformed endothelial cells.

These cells produce collagens I, III and V and fibronectin 1.

Resident fibroblasts likely represent only a small fraction of aortic collagen-producing cells in hypertension.

What is relevant?

Aortic stiffening occurs in hypertension and promotes end-organ damage and worsens blood pressure elevation.

The present study confirms the dynamic nature of the adventitia as a site of vascular remodeling and inflammation.

Adventitial cells of several types are sources of collagen, and likely contribute to aortic stiffening in other conditions.

Summary

In the present study, we identified three previously unidentified cellular sources of collagen that contribute to aortic fibrosis in hypertension. Resident fibroblasts, which are traditionally thought to contribute to this process, represent only a minority of these cells. Future studies of aortic stiffening should consider the individual roles of Sca-1+ cells, bone marrow-derived cells and transformed endothelial cells in this process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Vanderbilt University Translational Pathology Shared Resources and Digital Histology Shared Resources for their service of embedding and sectioning of tissues. The confocal imaging was performed with the assistance of the Cell Imaging Shared Resources (CISR) at Vanderbilt University. We also thank Dr. Olga A. Cherepanova and Mr. Alexander Young at the Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center, University of Virginia for their assistance in harvesting tissues from the smooth muscle lineage-tracing mice.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

NIH R01 Grants HL105294 and HL039006, HL057353, HL123650 and RO1-HL121877U01, HL100398 and Program Project Grants P01 HL58000 and GM015431, an American Heart Association pre-doctoral fellowship to Jing Wu and a post-doctoral fellowship award to Drs. Kirabo and Saleh. David Paik received support from T32 HL007411.

Jing Wu: Recipient of American Heart Association Pre-doctoral support

Kim Ramil C. Montaniel: Recipient of American Heart Association Pre-doctoral support

Mohamed A. Saleh: Recipient of American Heart Association Post-doctoral support

Gary K. Owens: Recipient of funding from the National Institutes of Health

Jay D. Humphrey: Recipient of funding from the National Institutes of Health

Mark W. Majesky: Recipient of funding from the National Institutes of Health

David T. Paik: Recipient of funding from the National Institutes of Health

Antonis K. Hatzopoulos: Recipient of funding from the National Institutes of Health

Meena S. Madhur: Recipient of funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association and Gilead Corporation

David G. Harrison: Recipient of funding from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Sca-1

Stem cell antigen 1

- EGFP

Enhanced green fluorescence protein

- EndoMT

Endothelial to mesenchymal transition

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Liang Xiao: Nothing to disclose

Wei Chen: Nothing to Disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitchell GF, Hwang SJ, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Pencina MJ, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Levy D, Benjamin EJ. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 2010;121:505–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper LL, Rong J, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Vita JA, Hamburg NM, Vasan RS, Mitchell GF. Components of hemodynamic load and cardiovascular events: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 2015;131:354–361. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011357. discussion 361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Trott DW, Saleh MA, Xiao L, Madhur MS, Chen W, Harrison DG. Inflammation and mechanical stretch promote aortic stiffening in hypertension through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Circ Res. 2014;114:616–625. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecker L, Vittal R, Jones T, Jagirdar R, Luckhardt TR, Horowitz JC, Pennathur S, Martinez FJ, Thannickal VJ. Nadph oxidase-4 mediates myofibroblast activation and fibrogenic responses to lung injury. Nat Med. 2009;15:1077–1081. doi: 10.1038/nm.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrakasan G, Bhatnagar RS. Stimulation of collagen synthesis in fibroblast cultures by superoxide. Cell Mol Biol. 1991;37:751–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majesky MW, Dong XR, Hoglund V, Mahoney WM, Jr, Daum G. The adventitia: A dynamic interface containing resident progenitor cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1530–1539. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Passman JN, Dong XR, Wu SP, Maguire CT, Hogan KA, Bautch VL, Majesky MW. A sonic hedgehog signaling domain in the arterial adventitia supports resident sca1+ smooth muscle progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9349–9354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711382105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu Y, Zhang Z, Torsney E, Afzal AR, Davison F, Metzler B, Xu Q. Abundant progenitor cells in the adventitia contribute to atherosclerosis of vein grafts in apoe-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1258–1265. doi: 10.1172/JCI19628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Psaltis PJ, Harbuzariu A, Delacroix S, Witt TA, Holroyd EW, Spoon DB, Hoffman SJ, Pan S, Kleppe LS, Mueske CS, Gulati R, Sandhu GS, Simari RD. Identification of a monocyte-predisposed hierarchy of hematopoietic progenitor cells in the adventitia of postnatal murine aorta. Circulation. 2012;125:592–603. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.059360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sainz J, Al Haj Zen A, Caligiuri G, Demerens C, Urbain D, Lemitre M, Lafont A. Isolation of "side population" progenitor cells from healthy arteries of adult mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:281–286. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000197793.83391.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakai N, Wada T, Yokoyama H, Lipp M, Ueha S, Matsushima K, Kaneko S. Secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (slc/ccl21)/ccr7 signaling regulates fibrocytes in renal fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14098–14103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia Y, Jin X, Yan J, Entman ML, Wang Y. Cxcr6 plays a critical role in angiotensin ii-induced renal injury and fibrosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1422–1428. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.303172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosin NL, Sopel M, Falkenham A, Myers TL, Legare JF. Myocardial migration by fibroblast progenitor cells is blood pressure dependent in a model of angii myocardial fibrosis. Hypertension research : official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension. 2012;35:449–456. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Molecular medicine. 1994;1:71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell JJ, Bowman EP, Murphy K, Youngman KR, Siani MA, Thompson DA, Wu L, Zlotnik A, Butcher EC. 6-c-kine (slc), a lymphocyte adhesion-triggering chemokine expressed by high endothelium, is an agonist for the mip-3beta receptor ccr7. The Journal of cell biology. 1998;141:1053–1059. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riol-Blanco L, Sanchez-Sanchez N, Torres A, Tejedor A, Narumiya S, Corbi AL, Sanchez-Mateos P, Rodriguez-Fernandez JL. The chemokine receptor ccr7 activates in dendritic cells two signaling modules that independently regulate chemotaxis and migratory speed. J Immunol. 2005;174:4070–4080. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeBleu VS, Taduri G, O'Connell J, Teng Y, Cooke VG, Woda C, Sugimoto H, Kalluri R. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/nm.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fioret BA, Heimfeld JD, Paik DT, Hatzopoulos AK. Endothelial cells contribute to generation of adult ventricular myocytes during cardiac homeostasis. Cell reports. 2014;8:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shankman LS, Gomez D, Cherepanova OA, Salmon M, Alencar GF, Haskins RM, Swiatlowska P, Newman AA, Greene ES, Straub AC, Isakson B, Randolph GJ, Owens GK. Klf4-dependent phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells has a key role in atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis. Nature medicine. 2015;21:628–637. doi: 10.1038/nm.3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinh A, Chen W, Blinder Y, Weiss D, Taylor WR, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM, Harrison DG, Guzik TJ. Inhibition and genetic ablation of the b7/cd28 t-cell costimulation axis prevents experimental hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:2529–2537. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boisset JC, van Cappellen W, Andrieu-Soler C, Galjart N, Dzierzak E, Robin C. In vivo imaging of haematopoietic cells emerging from the mouse aortic endothelium. Nature. 2010;464:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature08764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ieronimakis N, Hays AL, Janebodin K, Mahoney WM, Jr, Duffield JS, Majesky MW, Reyes M. Coronary adventitial cells are linked to perivascular cardiac fibrosis via tgfbeta1 signaling in the mdx mouse model of duchenne muscular dystrophy. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2013;63:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to cxcl12 and mediate fibrosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;114:438–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI20997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen PY, Qin L, Barnes C, Charisse K, Yi T, Zhang X, Ali R, Medina PP, Yu J, Slack FJ, Anderson DG, Kotelianski V, Wang F, Tellides G, Simons M. Fgf regulates tgf-beta signaling and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via control of let-7 mirna expression. Cell reports. 2012;2:1684–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.