Abstract

Background

Advanced age and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are associated with increased pneumococcal disease risk. The impact of these factors on cellular responses to vaccination is unknown.

Methods

HIV-infected (HIV+) individuals 50–65 years old with CD4+ T cells/μl (CD4) >200 on antiretroviral therapy (ART) 1 year received either the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine followed by the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PCV/PPV) or PPV only. HIV-uninfected (HIV−) controls received PCV/PPV. Phenotype distribution and surface expression of complement receptor CD21 and tumor necrosis factor superfamily receptors were compared on serotype-specific B cells postvaccination.

Results

Postvaccination serotype-specific B cell percentages were significantly lower in HIV+ PCV/PPV compared to PPV groups, but similar between HIV+ or HIV− PCV/PPV groups. Transmembrane activator and calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI)+ serotype-specific B cell percentages were significantly decreased in HIV+ PCV/PPV compared to PPV groups. CD21+ serotype-specific B cells were significantly higher in HIV− compared to HIV+ PCV/PPV groups.

Conclusions

An initial dose of PCV reduced the frequency, but not phenotype distribution, of serotype-specific B cells and also lowered TACI expression in aging HIV+ subjects postvaccination with PPV. These findings suggest that PCV does not enhance cellular responses to revaccination with PPV.

Keywords: HIV infection, aging, B cells, Streptococcus pneumoniae, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine

1. Introduction

The success of ART has led to a substantial increase in life expectancy for HIV+ individuals [1]. Approximately one-half of HIV+ individuals living in the United States are estimated to be ≥50 years old [2]. Aging and HIV infection both result in profound immunological changes due to chronic antigenic stress [2–5]. Similarities and differences, as well as the synergism, between these processes remain poorly understood.

PPV immunization generates impaired antibody responses in both elderly and HIV+ individuals, and effectiveness in preventing pneumococcal disease is controversial [6–9]. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) currently recommends that HIV+ adults receive a single dose of PCV followed by a dose of PPV 8 weeks later (PCV/PPV) [10]. Superiority of PCV, however, is also questionable, as immunogenicity studies comparing single doses or combined regimens of PCV and PPV have yielded variable results [11–16].

Further investigation into the underlying cellular mechanisms responsible for pneumococcal vaccine responses is urgently needed. In humans, evidence suggests that both IgM and switched memory B cells generate antibodies to pneumococcal antigens [17]. Several studies have reported an association between reduced memory B cell subsets and impaired responses to vaccination in elderly and HIV+ individuals [18–21]. However, these analyses were performed on total rather than antigen-specific B cell populations.

We have previously characterized the phenotype of B cells responding to PPV in young adults, elderly, and HIV+ [22–25]. The majority of serotype-specific B cells are IgM memory B cells in young, immunocompetent adults [22, 23]. Both elderly and HIV+ adults exhibit significant reductions in this subset that may contribute to decreased vaccine responsiveness [23–25]. However, unlike the elderly, HIV+ adults lack an increase in the proportion of serotype-specific switched memory B cells. Our data suggest that elderly and HIV+ individuals exhibit distinct perturbations in B cell subsets critical for protection against pneumococcal disease.

Older HIV+ individuals may possess a unique cellular response to vaccination reflecting the combined effects of aging and HIV infection. In the present study, we assessed the phenotype of B cells responding to the recommended PCV/PPV regimen compared to a single dose of PPV in HIV+ adults aged 50–65 years. We also sought to identify differences in surface expression of B cell receptors, including complement receptor CD21 and tumor necrosis factor superfamily receptors (TNFRs) CD40, TACI, and B cell-activating factor receptor (BAFF-R), on serotype-specific B cells that may contribute to vaccine responses.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Volunteers 50–65 years old were recruited between April 2012 and January 2015 in this University of Toledo Institutional Review Board-approved study. Written, informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Exclusion criteria included: active infection (except HIV), PPV <5 years prior, pregnancy, immunosuppressive medications, and prior history of splenectomy or other immunocompromising conditions as defined by ACIP vaccination recommendations [10]. Volunteers were questioned about any past hospitalizations. Eligibility criteria for HIV+ participants were further defined as current CD4>200, HIV viral load ≤400 copies/ml, and ART for ≥1 year. HIV– controls received a single dose of PCV (Prevnar 13®; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) at enrollment followed by one dose of PPV (Pneumovax 23®; Merck & Co., Inc.) 8 weeks later (PCV/PPV). HIV+ individuals received either PCV/PPV or a single dose of PPV.

2.2. Characterization of serotype-specific B cells

Blood samples were obtained from participants at enrollment and 1 week postvaccination (post-PPV or post-PCV). Total lymphocyte counts were determined using complete blood counts (CBC) with differential. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated and stained as previously described [22–25]. Fluorescently-labeled pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPS) or monoclonal antibodies (BD Biosciences or eBioscience) to the following antigens were used: PPS14-CB, PPS23F-DTAF, CD19 (SJ25C1, APC-Cy7), CD27 (323, PerCP-Cy5.5), IgM (SA-DA4, APC), BAFF-R (8A7, PE), TACI (11H3, PE), CD40 (5C3, PeCy7), and CD21 (B-Iy4, BV421). Total and serotype-specific IgM memory B cells (CD19+CD27+IgM+) and switched memory B cells (CD19+CD27+IgM−) were identified as previously described by our laboratory [22–25]. Total and serotype-specific B cells were further characterized for expression of CD21, CD40, BAFF-R, and TACI. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a FACSAria with FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) and data files were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 7.6.5, Tree Star).

2.3. Serotype-specific antibody responses

Quantitative and functional antibody responses at baseline and 1 month post-PPV in study subjects were assessed in a separate study (manuscript submitted). Serotype-specific IgM and IgG serum levels and opsonophagocytic killing assay (OPA) titers were determined as previously described [22–25].

2.4. Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics are represented as median (interquartile range, IQR) for numerical values and number (percentage) for categorical values. Summary statistics for B cell percentages and counts are expressed as median (IQR). Absolute numbers of total CD19+ B cells (cells/μl) for each subject were calculated by multiplying the percentage as determined by flow cytometry with the lymphocyte count. Baseline comparisons between groups were analyzed by Kruskal Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction. Comparisons of pre- to postvaccination serotype-specific B cell percentages were performed using the paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Postvaccination comparisons between groups (HIV+ PPV and HIV+ PCV/PPV or HIV+ PCV/PPV and HIV− PCV/PPV) were analyzed using pair-wise multiple comparison. Correlations between serotype-specific B cell subsets and antibody responses were determined by Spearman’s correlation coefficient. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software package (version 9.3; SAS Institute). P values <0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. Differences in the distribution of sex and race in HIV− compared to HIV+ subjects were noted. Clinical characteristics, including CD4 count at enrollment and use of ART, were similar between HIV+ groups. A larger proportion of HIV+ participants had been immunized with PPV ≥5 years prior (85%) compared to HIV− (7%). Quantitative and qualitative antibody responses to pneumococcal vaccination were assessed in a separate study (submitted manuscript). Total median B cell percentages and counts were significantly higher in the HIV+ PCV/PPV group compared to HIV+ PPV or HIV−PCV/PPV groups at baseline (P<0.006).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | HIV-infected

|

HIV-uninfected PCV/PPV (n = 14) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPV (n = 19) | PCV/PPV (n = 15) | ||

| Demographic | |||

| Median age (IQR) | 55.0 (51–59) | 54.0 (52–58) | 55.5 (52–58) |

| Male (%) | 17 (90) | 12 (80) | 6 (43) |

| Race (%) | |||

| Black | 7 (37) | 8 (53) | 1 (7) |

| White | 12 (63) | 5 (33) | 12 (86) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 1 (7) |

| Clinical History | |||

| Prior PPV ≥5 years (%) | 16 (84) | 13 (87) | 1 (7) |

| Receiving ART ≥1 year (%) | 19 (100) | 15 (100) | N/A |

| Nadir CD4+ T cell count | |||

| >200 (%) | 9 (47) | 5 (33) | N/A |

| ≤200 (%) | 10 (53) | 10 (67) | N/A |

| Immunological parameters | |||

| HIV viral load (copies/ml) | |||

| ≤400 (%) | 19 (100) | 15 (100) | N/A |

| CD4+ T cells (cells/μl) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 525 (336–976) | 576 (503–990) | N/A |

| CD19+ B cells (cells/μl) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 165 (76–242)* | 297 (216–382) | 137 (85–185)* |

| CD19+ B cells (%) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (5–13)* | 13 (10–17) | 8 (6–11)* |

PCV/PPV groups received PCV followed by PPV 8 weeks later. Data are no. (%) of subjects, unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PPV, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; PCV, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; IQR, interquartile range.

P <0.05 compared to HIV-infected PCV/PPV.

3.2. Serotype-specific B cell percentages are lower after PCV/PPV

Using fluorescently-labeled PPS, we evaluated circulating median serotype-specific B cell percentages in subjects pre- and 1 week post-PCV or -PPV (Table 2) as previously described [22–25]. No significant differences in prevaccination serotype-specific B cell percentages were observed between groups. Serotype-specific B cell percentages significantly increased post-PPV for both serotypes in the HIV+ PPV group (P<0.0001). In the HIV+ PCV/PPV group, significant increases in serotype-specific B cells were observed for serotype 23F only post-PCV (P = 0.02) and for both serotypes post-PPV (P<0.01) compared to prevaccination levels. In the HIV group, serotype-specific B cells increased significantly post-PCV for serotype 23F only (P = 0.03) and post-PPV for both serotypes (P<0.02). No significant differences between post-PCV and post-PPV serotype-specific B cell percentages were observed within HIV+ or HIV−PCV/PPV groups.

Table 2.

Pneumococcal polysaccharide-specific CD19+ B cell percentages to the indicated serotypes in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected subjects.

| Serotype 14 Median (IQR) | Serotype 23F Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| HIV-infected PPV (%) | ||

| Prevaccination | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) |

| 1 week post-PPV | 2.8 (1.5–4.0)* | 2.8 (1.5–3.9)* |

|

| ||

| HIV-infected PCV/PPV (%) | ||

| Prevaccination PCV | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 0.6 (0.4–0.7) |

| 1 week post-PCV | 0.7 (0.6–1.2) # | 0.7 (0.6–1.0)*, # |

| Prevaccination PPV | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.6 (0.3–0.8) |

| 1 week post-PPV | 1.1 (0.9–1.5)*, # | 1.1 (0.7–1.4)*, # |

|

| ||

| HIV-uninfected PCV/PPV (%) | ||

| Prevaccination PCV | 0.9 (0.8–1.4) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) |

| 1 week post-PCV | 1.9 (0.8–2.3) | 1.0 (0.6–1.1)* |

| Prevaccination PPV | 0.7 (0.6–1.0) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) |

| 1 week post-PPV | 1.7 (1.3–2.0)* | 1.1 (0.7–1.6)* |

PCV/PPV groups received PCV followed by PPV 8 weeks later.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PPV, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; PCV, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; IQR, interquartile range.

P <0.05 compared to prevaccination level within group.

P <0.05 compared to postvaccination HIV-infected PPV level between groups.

Comparisons of postvaccination serotype-specific B cell percentages were evaluated between HIV+ PPV and PCV/PPV groups or HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups. Both post-PCV and post-PPV serotype-specific B cell percentages were significantly lower in the HIV+ PCV/PPV group compared to the HIV+ PPV group post-PPV (P<0.007). In contrast, post-PCV and post-PPV serotype-specific B cell percentages were similar between HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups.

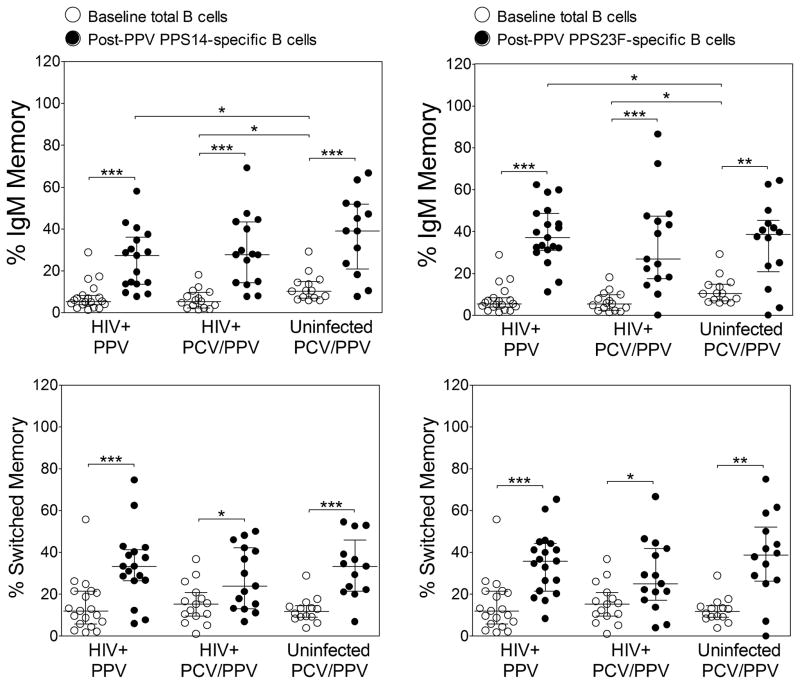

3.3. Serotype-specific memory B cell subset percentages are similar after PPV or PCV/PPV

We assessed median frequencies of total B cell memory subsets at baseline by flow cytometry (Figure 1). IgM memory B cell percentages in HIV+ PPV and PCV/PPV groups were significantly lower compared to the HIV− PCV/PPV group (P = 0.01). Switched memory B cell percentages were similar between groups.

Figure 1. Total and pneumococcal polysaccharide-specific memory CD19+ B cell subset percentages to the indicated serotypes in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected subjects.

Percentages of total and serotype-specific IgM memory (CD19+CD27+IgM+, upper panels) and switched memory (CD19+CD27+IgM−, lower panels) B cell subsets were measured by flow cytometry in HIV-infected PPV (PPS14, n=17; PPS23F, n=19), HIV-infected PCV/PPV (PPS14 and PPS23F, n=15), and HIV-uninfected PCV/PPV (PPS14, n=13; PPS23F, n=14) groups. PCV/PPV groups received PCV followed by PPV 8 weeks later. Graphs represent total B cell percentages at baseline and serotype-specific B cell percentages 1 week after vaccination with PPV (post-PPV). Left panels represent PPS14-specific B cell percentages and right panels represent PPS23F-specific B cell percentages. Scatter dot plots include median (horizontal black line) with interquartile range. Abbreviations: PPS, pneumococcal polysaccharide; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PPV, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; PCV, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

We compared the phenotypic distribution of serotype-specific B cells between HIV+ PPV and PCV/PPV groups and between HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups 1 week post-PPV (Figure 1). Serotype-specific B cells were subdivided into IgM memory and switched memory subsets as previously described [22–25]. No significant differences in median serotype-specific IgM and switched memory B cell percentages were observed between HIV+ PPV and HIV+ PCV/PPV groups. Serotype-specific IgM and switched memory B cell percentages were also similar post-PPV in HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups. Serotype-specific IgM memory and switched memory B cell percentages were evenly distributed within study groups for both serotype 14 (HIV+ PPV, 27.3% and 33.3%; HIV+ PCV/PPV, 27.7% and 24.0%; HIV− PCV/PPV, 39.0% and 33.3%) and serotype 23F (HIV+ PPV, 37.1% and 35.8%; HIV+ PCV/PPV, 26.8% and 25.0%; HIV− PCV/PPV, 38.6% and 38.8%) post-PPV. A similar pattern was observed in serotype-specific B cell memory subsets post-PCV in HIV+ and HIV−PCV/PPV groups (data not shown). For all study groups, median percentages of post-PPV serotype-specific memory B cells were significantly higher than baseline total B memory cells (P<0.02, Figure 1).

There were significant correlations between post-PPV serotype-specific IgM memory B cell percentages and post-PPV antibody responses in the HIV+ PPV group. PPS14-specific IgM memory B cells correlated with serotype 14 OPA titers (r = 0.75, P = 0.0006), and PPS23F-specific IgM memory B cells correlated with PPS23F-specific IgM levels (r = 0.52, P = 0.02). No significant correlations were observed in HIV+ or HIV− PCV/PPV groups between post-PPV or post-PCV serotype-specific memory B cells and post-PPV antibody responses.

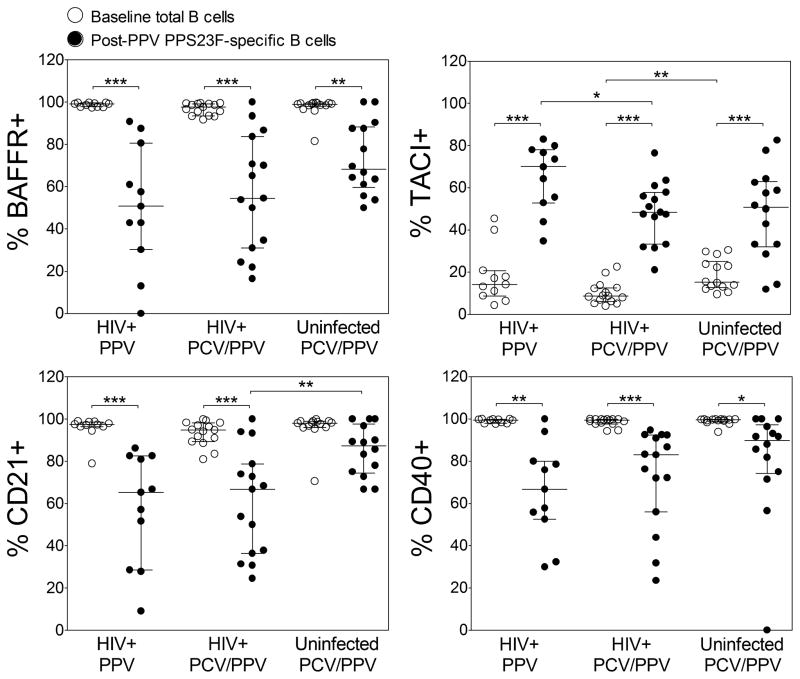

3.4. Serotype-specific TACI+ B cell percentages are lower after PCV/PPV

Surface expression of complement receptor CD21 and TNFRs CD40, BAFF-R, and TACI on total B cells were assessed at baseline (Figure 2). Median percentages of total BAFF-R+, CD21+, and CD40+ B cells were similar between study groups. Total TACI+ B cells percentages were also similar between HIV+ groups. However, TACI+ B cell percentages were decreased in HIV+ compared to HIV− PCV/PPV groups (P = 0.003).

Figure 2. Surface expression of B cell receptors on total and pneumococcal polysaccharide-specific CD19+ B cells in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected subjects.

Percentages of BAFF-R, TACI, CD21, and CD40 positive total and PPS23F-specific CD19+ B cells were determined by flow cytometry in HIV+ PPV (n=11), HIV+ PCV/PPV (n=15), and HIV− PCV/PPV (n=16) subjects. PCV/PPV groups received PCV followed by PPV 8 weeks later. Graphs represent total B cell percentages at baseline and serotype-specific B cell percentages 1 week after vaccination with PPV (post-PPV). Scatter dot plots include median (horizontal black line) with interquartile range. Abbreviations: PPS, pneumococcal polysaccharide; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PPV, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; PCV, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

We compared the expression of these receptors on serotype-specific B cells between HIV+ PPV and PCV/PPV groups and between HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups 1 week post-PPV (Figure 2). Median percentages of PPS23F-specific CD21+, CD40+, and BAFF-R+ B cells post-PPV were similar between HIV+ PPV and HIV+ PCV/PPV groups. In contrast, PPS23F-specific TACI+ B cell percentages were significantly higher in HIV+ PPV compared to HIV+ PCV/PPV groups (P = 0.03). PPS23F-specific TACI+ B cell percentages were similar in HIV+ compared to HIV− PCV/PPV groups. No significant differences in PPS23F-specific BAFF-R+ and CD40+ B cell percentages were observed between HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups. PPS23F-specific CD21+ B cell percentages were significantly lower in HIV+ compared to HIV−PCV/PPV groups (P = 0.02). No significant differences in these receptors were observed on post-PCV PPS23F-specific B cells in HIV+ compared to HIV− PCV/PPV groups (data not shown). Overall, significant differences in receptor expression were observed between post-PPV PPS23F-specific B cells and baseline total B cells in all study groups (P<0.01, Figure 2).

4. Discussion

In the current study, we assessed B cells responding to the recommended PCV/PPV regimen compared to a single dose of PPV in HIV+ adults 50–65 years old. We identified serotype-specific B cells using fluorescently-labeled PPS as previously described by our laboratory [22–25]. Serotype-specific B cell percentages post-PPV were significantly lower in the HIV+ PCV/PPV group compared to the HIV+ PPV group, suggesting that an initial dose of PCV limits the frequency of responding B cells after revaccination with PPV. In contrast, PPV or PCV/PPV in HIV+ subjects generated antibody responses of similar magnitudes (submitted manuscript). No significant differences in serotype-specific B cell percentages were observed between HIV+ and HIV− PCV+ PPV groups. However, post-PPV IgG levels and OPA titers were significantly reduced in the HIV+ PCV/PPV group, further emphasizing a discrepancy between serotype-specific cellular and antibody responses. We assessed peripheral blood samples 1 week postvaccination when the frequency of antigen-specific B cells is highest [22, 23, 26]. Analysis of circulating B cell populations excludes other B cell compartments, such as lymph node or spleen, where antigen-specific B cells may be located. PPS contained in PPV, due to their repetitive nature, activate B cells without direct T cell interactions and promote extrafollicular proliferation. Conjugation of PPS to an immunogenic carrier protein, as in PCV, is thought to preferentially drive antigen-specific B cells towards germinal center responses [27]. Thus, assessment of circulating serotype-specific B cells after PCV may not accurately represent the total population of responding B cells.

The phenotypic distribution of serotype-specific B cells was similar in HIV+ subjects regardless of whether they received PPV or PCV/PPV. Significant variations in serotype-specific antibody titers and antibody-secreting cells still occur with conjugate vaccines [28] despite induction of strong carrier-protein specific memory T cell responses [28, 29]. Therefore, the phenotype of serotype-specific B cells generated in response to PCV or PPV may be influenced by the existing B cell repertoire more so than the presence of T cell responses. In addition, no significant differences were observed in serotype-specific IgM and switched memory B cell percentages between HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups post-PCV or -PPV. Further investigation is needed to determine if alternative vaccination regimens including multiple doses of PCV will have the same impact on circulating serotype-specific B cells subsets.

Other studies have assessed B cell populations after conjugate vaccination in HIV+ or elderly subjects [30–32]. Reduced frequencies of circulating serotype-specific B cells in PCV/PPV participants observed in our study contrasts the findings of Baxendale et al. [31] and Clutterbuck et al. [32] who reported no change or increases in antigen-specific B cell populations with PCV compared to PPV, respectively. Marked differences in study design and time points, methodologies, vaccination regimens, and subjects render these studies incomparable. However, collectively these findings suggest memory B cell subsets are important for humoral responses to pneumococcal vaccination.

Evidence suggests IgM memory B cells in humans are critical for defense against pneumococcal infection [33]. We have previously observed significant correlations between serotype-specific IgM memory B cells and OPA titers in both HIV− and ART-treated HIV+ adults post-PPV [22, 24]. In the current study, post-PPV PPS14-specific IgM memory B cell percentages also significantly correlated with post-PPV serotype 14 OPA titers in the HIV+ PPV group. In contrast, serotype-specific IgM memory B cells poorly correlated with antibody responses in the HIV+ PCV/PPV group. This lack of correlation may be associated with the lower frequency of circulating serotype-specific B cells post-PCV and post-PPV. Postvaccination serotype-specific memory B cell subsets also poorly correlated with antibody responses in the HIV− PCV/PPV group. It remains to be determined whether testing total or serotype-specific memory B cell populations in high risk individuals, such as the elderly or HIV+, can be used to predict vaccine responses. Our findings suggest that associations between post-PPV serotype-specific B cells and antibody responses may be difficult to determine after an initial dose of PCV.

Complement receptor CD21 and TNFRs, including CD40, BAFF-R, and TACI, are critical in the generation of antibody responses to T cell-dependent (TD) and/or –independent (TI) antigens. BAFF-R and TACI are innate mediators of B cell differentiation, activation, and class switching [34]. We evaluated whether an initial dose of PCV alters surface expression of these receptors on PPS23F-specific B cells after revaccination with PPV. No significant differences in PPS23F-specific CD21+, CD40+, or BAFF-R+ B cell percentages were observed between HIV+ PPV or PCV/PPV groups. In contrast, PPS23F-specific TACI+ B cells percentages post-PPV were significantly higher in HIV+ PPV compared to HIV+ PCV/PPV groups, suggesting that PCV influences TACI expression after subsequent vaccination with PPV. Moreover, no significant differences were observed in TACI+ PPS23F-specific B cells percentages post-PPV in HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups.

TACI is essential for humoral responses to TI antigens including PPS [34, 35]. Individuals at high risk for pneumococcal disease, including infants and subgroups of common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) patients, exhibit decreased antibody secretion due to reduced [36] or mutated [37] TACI expression. Higher percentages of PPS23F-specific TACI+ B cells post-PPV observed in the HIV+ PPV group further support a role for TACI in TI responses. TACI is also thought to be a negative regulator of CD40-mediated antibody production [34, 38]. We observed a significant, negative correlation between TACI+ and CD40+ PPS23F-specific B cells in the HIV+ PPV group (r = −0.63, P = 0.04), but not PCV/PPV group (r = −0.17, P = 0.54). The molecular mechanisms responsible for differential expression remain to be investigated. Alternatively, our findings may represent PPS-induced hyporesponsiveness to PPV and not a direct effect of prior PCV. However, this is unlikely as PPS23F-specific TACI+ B cell percentages post-PCV were similar to post-PPV in both HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups (data not shown).

CD21 provides a critical secondary signal for B cell activation in response to TI antigens, and reduced expression is associated with impaired antibody responses to PPS [39, 40]. HIV viremia results in expansion of abnormal peripheral CD21lo B cells associated with exhaustion and increased cell turnover [41, 42]. Control of viremia with ART appears to significantly reduce these populations [43]. Consistent with this finding, no difference was observed in CD21 expression on total B cells between HIV+ and HIV− PCV/PPV groups. However, PPS23F-specific CD21+ B cell percentages post-PPV were significantly lower in HIV+ compared to HIV− PCV/PPV groups and may contribute to the diminished antibody responses generated in our HIV+ subjects (submitted manuscript).

We recognize that the current study has limitations. Although our sample size was limited, we observed distinct differences in serotype-specific B cell responses to PPV compared to PCV/PPV. It is unclear whether PCV has a similar impact on other vaccine serotypes. In addition, we were unable to evaluate TNFR expression on serotype-specific IgM and switched memory B cell subpopulations due to the low frequency of cells available for analysis. It thus remains to be determined whether TNFR expression is differentially regulated on serotype-specific B cell memory subsets.

Collectively, our findings indicate that an initial dose of PCV alters the overall frequency and surface TACI expression of serotype-specific B cells after revaccination with PPV. It remains unclear whether the alterations due to prior PCV confer any immunological advantage, as postvaccination antibody responses in HIV+ PPV and PCV/PPV groups were similar (submitted manuscript). In contrast, PCV had no impact on the phenotypic distribution of serotype-specific B cells. Our study emphasizes the need for continued investigation into signaling mechanisms that regulate B cell responses. Utilization of TI and/or TD stimuli to enhance B cell responses may be the key to improving pneumococcal vaccination strategies in high risk adult populations, such as the aging HIV+, where vaccine responses are suboptimal. Evidence from murine studies indicates that Toll-like receptors (TLRs) can serve as effective adjuvants to both TI and TD components of encapsulated bacteria [34, 35]. In support of this concept, addition of a TLR9 agonist to the 7-valent conjugate vaccine increased the proportion of HIV+ patients with high antibody responses [44].

Acknowledgments

We thank all study volunteers for their participation and the Division of Infectious Diseases physicians and staff at the University of Toledo Medical Center in Toledo, Ohio for their assistance with recruitment.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [RO1A081558 and RO1AG045973 to M.A.J.W.].

Abbreviations

- ACIP

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- BAFF-R

B cell-activating factor receptor

- CBC

complete blood count

- CD4

CD4+ T cells/μl

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- IQR

interquartile range

- OPA

opsonophagocytic killing assay

- PCV

13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

- PPS

pneumococcal polysaccharide

- PPV

23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine

- TACI

calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligand interactor

- TNFR

tumor necrosis superfamily receptor

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, Modur SP, Althoff KN, Buchacz K, et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PloS one. 2013;8:e81355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, Halter JB, Hazzard WR, Horne FM, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008;47:542–53. doi: 10.1086/590150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB, Cohen MH, Currier J, Deeks SG, et al. HIV and aging: state of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2012;60(Suppl 1):S1–18. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825a3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Biasi S, Pinti M, Nasi M, Gibellini L, Bertoncelli L, Manzini S, et al. HIV-1 Infection and the Aging of the Immune System: Facts, Similarities and Perspectives. J Exp Clin Med. 2011;3:143–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annual review of medicine. 2011;62:141–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedersen RH, Lohse N, Ostergaard L, Sogaard OS. The effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in HIV-infected adults: a systematic review. HIV medicine. 2011;12:323–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dworkin MS, Ward JW, Hanson DL, Jones JL, Kaplan JE, Adult, et al. Pneumococcal disease among human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons: incidence, risk factors, and impact of vaccination. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2001;32:794–800. doi: 10.1086/319218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moberley S, Holden J, Tatham DP, Andrews RM. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;1:CD000422. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000422.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huss A, Scott P, Stuck AE, Trotter C, Egger M. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults: a meta-analysis. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. 2009;180:48–58. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2012;61:816–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feikin DR, Elie CM, Goetz MB, Lennox JL, Carlone GM, Romero-Steiner S, et al. Randomized trial of the quantitative and functional antibody responses to a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and/or 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine among HIV-infected adults. Vaccine. 2001;20:545–53. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crum-Cianflone NF, Huppler Hullsiek K, Roediger M, Ganesan A, Patel S, Landrum ML, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing revaccination with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to polysaccharide vaccine among HIV-infected adults. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;202:1114–25. doi: 10.1086/656147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho YL, Brandao AP, de Cunto Brandileone MC, Lopes MH. Immunogenicity and safety of pneumococcal conjugate polysaccharide and free polysaccharide vaccines alone or combined in HIV-infected adults in Brazil. Vaccine. 2013;31:4047–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lesprit P, Pedrono G, Molina JM, Goujard C, Girard PM, Sarrazin N, et al. Immunological efficacy of a prime-boost pneumococcal vaccination in HIV-infected adults. Aids. 2007;21:2425–34. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282887e91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu CL, Chang SY, Chuang YC, Liu WC, Su CT, Su YC, et al. Revaccination with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine elicits better serologic response than 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in HIV-infected adult patients who have undergone primary vaccination with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Vaccine. 2014;32:1031–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penaranda M, Payeras A, Cambra A, Mila J, Riera M Majorcan Pneumococcal Study G. Conjugate and polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccines do not improve initial response of the polysaccharide vaccine in HIV-infected adults. Aids. 2010;24:1226–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283389de5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moens L, Wuyts M, Meyts I, De Boeck K, Bossuyt X. Human memory B lymphocyte subsets fulfill distinct roles in the anti-polysaccharide and anti-protein immune response. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:5306–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Titanji K, De Milito A, Cagigi A, Thorstensson R, Grutzmeier S, Atlas A, et al. Loss of memory B cells impairs maintenance of long-term serologic memory during HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2006;108:1580–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-013383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hart M, Steel A, Clark SA, Moyle G, Nelson M, Henderson DC, et al. Loss of discrete memory B cell subsets is associated with impaired immunization responses in HIV-1 infection and may be a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease. Journal of immunology. 2007;178:8212–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Orsogna LJ, Krueger RG, McKinnon EJ, French MA. Circulating memory B-cell subpopulations are affected differently by HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2007;21:1747–52. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32828642c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Y, Yamazaki T, Okubo Y, Uehara Y, Sugane K, Agematsu K. Regulation of aged humoral immune defense against pneumococcal bacteria by IgM memory B cell. Journal of immunology. 2005;175:3262–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khaskhely N, Mosakowski J, Thompson RS, Khuder S, Smithson SL, Westerink MA. Phenotypic analysis of pneumococcal polysaccharide-specific B cells. Journal of immunology. 2012;188:2455–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leggat DJ, Thompson RS, Khaskhely NM, Iyer AS, Westerink MA. The immune response to pneumococcal polysaccharides 14 and 23F among elderly individuals consists predominantly of switched memory B cells. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;208:101–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyer AS, Leggat DJ, Ohtola JA, Duggan JM, Georgescu CA, Rizaiza AAA, et al. Response to Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccination in HIV-Positive Individuals on Long Term Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. J AIDS Clin Res. 2015;6 doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leggat DJ, Iyer AS, Ohtola JA, Kommoori S, Duggan JM, Georgescu CA, et al. Response to Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccination in Newly Diagnosed HIV-Positive Individuals. J AIDS Clin Res. 2015;6 doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odendahl M, Mei H, Hoyer BF, Jacobi AM, Hansen A, Muehlinghaus G, et al. Generation of migratory antigen-specific plasma blasts and mobilization of resident plasma cells in a secondary immune response. Blood. 2005;105:1614–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paus D, Phan TG, Chan TD, Gardam S, Basten A, Brink R. Antigen recognition strength regulates the choice between extrafollicular plasma cell and germinal center B cell differentiation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:1081–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamboj KK, Kirchner HL, Kimmel R, Greenspan NS, Schreiber JR. Significant variation in serotype-specific immunogenicity of the seven-valent Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide-CRM197 conjugate vaccine occurs despite vigorous T cell help induced by the carrier protein. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2003;187:1629–38. doi: 10.1086/374785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabian C, Tschope I, Lesprit P, Katlama C, Molina JM, Meynard JL, et al. Cellular CD4 T cell responses to the diphtheria-derived carrier protein of conjugated pneumococcal vaccine and antibody response to pneumococcal vaccination in HIV-infected adults. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;50:1174–83. doi: 10.1086/651418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johannesson TG, Sogaard OS, Tolstrup M, Petersen MS, Bernth-Jensen JM, Ostergaard L, et al. The impact of B-cell perturbations on pneumococcal conjugate vaccine response in HIV-infected adults. PloS one. 2012;7:e42307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baxendale HE, Keating SM, Johnson M, Southern J, Miller E, Goldblatt D. The early kinetics of circulating pneumococcal-specific memory B cells following pneumococcal conjugate and plain polysaccharide vaccines in the elderly. Vaccine. 2010;28:4763–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clutterbuck EA, Lazarus R, Yu LM, Bowman J, Bateman EA, Diggle L, et al. Pneumococcal conjugate and plain polysaccharide vaccines have divergent effects on antigen-specific B cells. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;205:1408–16. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kruetzmann S, Rosado MM, Weber H, Germing U, Tournilhac O, Peter HH, et al. Human immunoglobulin M memory B cells controlling Streptococcus pneumoniae infections are generated in the spleen. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;197:939–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerutti A, Puga I, Cols M. Innate control of B cell responses. Trends in immunology. 2011;32:202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schreiber JR. Role of Toll like receptors in the antibody response to encapsulated bacteria. Frontiers in bioscience. 2012;4:2638–46. doi: 10.2741/e571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaur K, Chowdhury S, Greenspan NS, Schreiber JR. Decreased expression of tumor necrosis factor family receptors involved in humoral immune responses in preterm neonates. Blood. 2007;110:2948–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castigli E, Wilson SA, Garibyan L, Rachid R, Bonilla F, Schneider L, et al. TACI is mutant in common variable immunodeficiency and IgA deficiency. Nature genetics. 2005;37:829–34. doi: 10.1038/ng1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakurai D, Kanno Y, Hase H, Kojima H, Okumura K, Kobata T. TACI attenuates antibody production costimulated by BAFF-R and CD40. European journal of immunology. 2007;37:110–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vos Q, Lees A, Wu ZQ, Snapper CM, Mond JJ. B-cell activation by T-cell-independent type 2 antigens as an integral part of the humoral immune response to pathogenic microorganisms. Immunological reviews. 2000;176:154–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeurissen A, Ceuppens JL, Bossuyt X. T lymphocyte dependence of the antibody response to ‘T lymphocyte independent type 2′ antigens. Immunology. 2004;111:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2003.01775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moir S, Fauci AS. B cells in HIV infection and disease. Nature reviews Immunology. 2009;9:235–45. doi: 10.1038/nri2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moir S, Malaspina A, Ho J, Wang W, Dipoto AC, O’Shea MA, et al. Normalization of B cell counts and subpopulations after antiretroviral therapy in chronic HIV disease. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2008;197:572–9. doi: 10.1086/526789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moir S, Buckner CM, Ho J, Wang W, Chen J, Waldner AJ, et al. B cells in early and chronic HIV infection: evidence for preservation of immune function associated with early initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Blood. 2010;116:5571–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-285528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sogaard OS, Lohse N, Harboe ZB, Offersen R, Bukh AR, Davis HL, et al. Improving the immunogenicity of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in HIV-infected adults with a toll-like receptor 9 agonist adjuvant: a randomized, controlled trial. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;51:42–50. doi: 10.1086/653112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]