Abstract

People affected by substance use disorders often experience sub-optimal employment outcomes. The role of drug use in processes that produce and entrench labour market precarity among people who inject drugs (PWID) have not, however, been fully described. We recruited 22 PWID from ongoing prospective cohort studies in Vancouver, Canada and conducted semi-structured retrospective interviews and employed a thematic analysis that draws on concepts from life course theory to explore mechanisms and pathways linking drug use and labour market trajectories. Narratives identified processes corresponding to: causation, whereby suboptimal employment outcomes led to harmful drug use; direct selection, where impairment, health complications or drug seeking activities selected individuals out of employment; and indirect selection, where external factors, such as catastrophic events, marked the initiation or intensification of substance use concurrent with sudden changes in capacities for employment. Catastrophic events linking negative transitions in both drug use and labour market trajectories were of primary importance, demarcating critical initiation and transitional events in individual risk trajectories. These results challenge conventional assumptions about the primacy of drug use in determining employment outcomes among PWID, and suggest the importance of multi-dimensional supports to mitigate the initiation, accumulation and entrenchment of labour market and drug-related disadvantage.

Keywords: Life course, drug use, employment, causality, catastrophic events

Background

People living with substance use disorders commonly experience socio-economic vulnerability in the form of income or material insecurity (Ompad et al 2012; Long et al 2014) or unemployment (Henkel 2011). Poverty and poor health among people who use drugs represent longstanding, intractable and overlapping syndemics crossing biological, social and structural conditions (Singer, & Clair 2003). The dynamics of such syndemics link interrelated domains in which vulnerability and marginalization manifest, recognizing that “drug abuse is related to housing is related to health care is related to joblessness is related to poverty” (Shavelson 2001). That is, socio-economic vulnerability impacts and is impacted by drug use and drug-related harm in a complex intertwining of health, social and economic trajectories. Disentangling these relationships is theoretically and empirically relevant because of their role in pathways into and out of harmful drug use and their significant implications for public health and labour market policy as well as programmatic interventions.

Among the harms resulting from substances use, lost productivity is cited as one of the most significant substance use-related costs (Heien, & Pittman 1989; Reuter 1999). Lost productivity includes: (1) foregone economic contributions because of premature mortality and disability; (2) absenteeism; (3) impaired productivity because of substance related illness, treatment, injury or disability; and (4) crime-related costs, including the incarceration of perpetrators, or the costs to victims of substance-related crime (Bouchery et al 2011; National Drug Intelligence Center [NDIC] 2011). These costs have been estimated at $120.3 billion (USD) in the United States and $24.3 billion (CAD) in Canada, or 62.3% and 61% of the total costs attributed to drug use respectively (NDIC 2011; Rehm et al 2007). Consistent with previous research that explores the relationship between drug use and work (Draus et al 2010; Kaestner 1998; Platt 1995; McCoy et al 2007), these figures implicate drug use in suboptimal employment outcomes. In contrast, other research has suggested that unemployment may elevate levels of problematic substance use (Henkel 2011; Pearson 1987; Bourgois & Schonberg 2009). Such analyses reveal expectations of causal direction, anticipating that drug use produces decreased labour market participation or vice versa. However, given equivocal conclusions from previous quantitative research (Kaestner 1998), the aim of the current study is to examine the relationship between drug use and work by exploring the trajectories and mechanisms linking these two domains.

Examinations of such patterning are usefully informed by research on labour market participation as a social determinant of health, which examines how socio-economic status, labour market outcomes and unemployment relate to health inequities (Bambra 2011; Bartley 1994; van der Wel 2011). There is considerable debate whether this relationship is characterised by causation, whereby unemployment produces poorer health outcomes, the direct health selection of individuals in poorer health out of employment, or the indirect selection effect of a third factor or interrelated factors that produce suboptimal outcomes in both areas (Blane et al 1993; Ross, & Mirowsky 1995). There is a growing consensus that processes of both selection and causation are applicable to the consistent association found between employment and health (Bartley 1988; McDonough, & Amick 2001).

Heterogeneous pathways inferred from previous research suggest the analytical utility of an approach that considers the health, social and economic pathways implicated in both work and drug use. In the case of drug use trajectories, which have been previously characterised as drug use “careers” (Anglin et al 1997), these pathways may include initiation, experimentation, escalation, habituation, problematic experiences, treatment, temporary abstinence, relapse, maturing out, retirement, disability, premature mortality or total abstinence (Shaw 2002). Life course perspectives on drug use focus on identifying factors, critical events and turning points contributing to persistence or change in drug use pathways (Hser et al 2007). Labour market trajectories may include similarly complex processes of capital accumulation, labour market entry, transitions into work, the maintenance of employment, job transitions, job losses and labour market exits (Rigg, & Sefton 2006; Virtanen et al 2005). Life course approaches to employment similarly focus on turning points, the accumulation of advantage and disadvantage and the importance of both proximal and distal individual, social and structural forces in the production of inequality along life course trajectories (Elder et al 2003). In both cases, processes of transition, accumulation and reinforcement are seen as critical in the production and maintenance of disadvantage.

While the current study does not involve cohort approaches common to life course analyses, it adopts key components of life course theory to retrospectively explore the relationship between drug use and work trajectories, with three specific objectives. First, it seeks to examine the underlying mechanisms through which this relationship is experienced, perceived and understood by PWID. Second, it aims to understand the implications of transitions, accumulation and mutual reinforcement in the production and maintenance of drug- and health-related disadvantage over time. Third, it seeks to complement existing quantitative research on the relationship between drug use and labour market outcomes through an improved understanding of the pathways that characterise this relationship.

Research Context

Deprived neighbourhoods, subject to concentrations of individual, social and structural vulnerabilities (Diez Roux 2001) are locales where labour market-, drug- and health-related disadvantage may accumulate in spatially defined urban environments (Browning, & Cagney 2002). Vancouver, Canada’s Downtown Eastside (DTES), an area of fifteen blocks directly east of Vancouver’s downtown core, is often identified as a site where dynamics of neighbourhood deprivation have had highly visible and harmful consequences (Smith 2003). High levels substance use increasingly characterised the area alongside concurrent economic decline in the mid to latter half of the 20th century (Campbell et al 2009). The emergence of HIV/AIDS in the injection drug using community in the 1990s resulted in an explosive HIV outbreak among PWID and their sexual partners, with HIV incidence among the highest in the developed world (Strathdee et al 1997). While rates of HIV incidence have decreased considerably, it remains a locus of open drug use and sales, endemic poverty, unstable housing, crime, high HIV prevalence and widespread mental illness (Wood et al 2007).

Labour market outcomes in the DTES are further indicative of significant localised disadvantage. While census data from 2006 indicate that the 11.3% unemployment rate among those 15 years and older in the DTES was higher than the Vancouver and national rates of 7.2% and 6.6% (Brethour 2009; City of Vancouver 2006) the rate of labour market participation in the DTES was 38.2%, just over half the Vancouver and Canadian national averages of 67.0% (Brethour 2009). Statistics Canada has identified a 2006 median income of $13,691 CAD compared to the Vancouver ($47,299) and national ($63,600) medians. The co-occurrence of drug use, labour market and health disadvantage in the DTES make it an appropriate milieu to explore individual labour market and drug use trajectories among PWID.

Data and methods

Participants for the current study were recruited from the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) and the AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS), long-running community recruited prospective cohort studies of HIV seronegative and seropositive people who use illicit drugs. The majority of participants reside in Vancouver’s DTES. Individuals were eligible for the current study if they were of adult working age (between 18–65 years old), had a history of injection drug use and provided written informed consent. Recruitment efforts selected individuals whose income generation and drug use trajectories could provide information on a broad range of experiences such as employment in different sectors of the economy, alternative income generation strategies and different types of drug use and drug use intensity. This recruitment strategy sought participants who could elucidate our research objectives from multiple perspectives (Creswell 2012). Individuals were informed of the study by VIDUS and ACCESS research staff, the study involved an informed consent process separate from that of the parent studies, and standard measures (e.g., the de-identification of data, use of pseudonyms, encryption of data files, etc.) were taken to ensure participant confidentiality and assure participants about the security of their study data. This study received ethics approval from the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board and the University of Oxford Central University Research Ethics Committee.

Semi-structured interviews explored current and past experiences of income generation and work among PWID, views and experiences related to the relationship between drug use and work, and perceptions and experiences of practices, behaviour and circumstances that operate as either barriers or facilitators to labour market engagement. Consistent with previous studies (Draus et al 2010) and concepts from life course theory described above, interviews focused on identifying linkages between drug use and employment within personal social histories. Individuals were paid $20CAD honoraria for their participation, consistent with previous research in this setting (Small et al 2007). No individual declined the invitation to participate. Interviews lasted between 30 and 120 minutes and were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were verified against interview recordings for accuracy and read several times to develop familiarity with the data. Interview data were sorted, labeled and coded using a word processing computer program.

The coding framework made use of themes derived from the pre-existing literature as well as emergent codes that arose from the content of the interviews. This blending of deductive and inductive analytical methods positioned this analysis in relation to points of reference identified by previous studies (Miles, & Huberman 1994), while extending our understanding of drug use and labour market pathways in the narrative construction of participant trajectories in previous research (Abell et al 2004). Coding focused specifically on the connections between events, sequences and consequences in the formulation of biographical events and individual life situations (Taylor, & Littleton 2006; Bruner 1987), paying particular attention to how these shaped work and drug use experiences, and the interactions between the two. This approach positioned respondents’ descriptions of their situations as the cumulative outcome of practices, decisions, circumstances and events that impacted drug use and labour market trajectories. All content related to each individual code was compiled, and the coded text segments were analyzed thematically to develop interpretations of the complex relationship between employment, income generation, drug use and related aspects of respondents’ lives.

Results

Descriptive Information

A total of 22 individuals participated in interviews for the current study, of whom the median age was 48 (interquartile range: 42–50). Eight participants were women (36.4%), 12 (54.5%) individuals were White, seven (31.8%) self-identified as having Aboriginal (i.e., Métis, Aboriginal, First Nations or Inuit) ancestry, and single (4.5%) individuals reported Southeast Asian, Latin American, or Black-Caribbean ethnicity. Drug use patterns at the time of interview were heterogeneous across participants. Only two (9.1%) participants reported no current illegal drug use; both had extensive drug use histories and one was currently enrolled in methadone maintenance therapy. The most common current illegal substance that participants reported using was smoked crack-cocaine (12 or 54.5% of participants). This was followed by injection heroin (40.9%), injection cocaine (31.8%), injection methamphetamine, speedball injection (i.e., combined heroin and cocaine) and use of cocaine powder (5.4% for each). Sixteen participants (72.7%) used multiple substances.

Four (18.2%) participants were engaged in the labour market at the time of interview. Seven (31.8%) individuals held formal stipendiary volunteering positions. Only three (13.6%) participants were not receiving some form of government assistance. Most supplemented government income with unreported, informal work doing construction, manual labour or odd jobs (36.4%), sex work (18.2%), drug dealing (18.2%), street-based income generation in the form of recycling cans, panhandling or windshield washing (13.6%), or other informal economic activity such as selling their artwork or goods on the street (5.4%). All but two participants (90.9%) had formal employment histories of reported economic activity. These roles traversed the socio-economic spectrum; while most reported employment in manual labour, construction, trades, or resource-based industries, employment roles also included senior administration, business ownership as well as professional and senior managerial positions.

Labour market impacts of drug use

Participants described multiple patterns of experiences and understandings of the relationship between drug use and work. Some participants described drug use as having direct, significant and deleterious impacts on labour market outcomes. Nearly one third of respondents indicated that for them, “it’s gotta be one or the other. You can’t have your cake and eat it too. It doesn’t happen” (Participant #2, male). This was not universally the case, however, as some participants conversely suggested that “I never missed work due to it [drugs]. That kind of thing, you know, last one out, first one in and all that stuff” (Participant #19, male). Participants that directly linked drug use as affecting their employment outcomes described instances where drug use rendered vocational responsibilities impossible to execute.

Why would I hire somebody who’s been a crackhead? He comes to work fried out of his face all the time. Why would you hire me like this when I wouldn’t hire me, I wouldn’t hire myself like this? (Participant #17, male)

I’d go in there all fucked right up and I would fuck everybody up, right? You have to be on the ball and you have to be really there, and when you’re not there, it totally shows. (Participant #2, male)

Consistent with the common hypothesis of an inverse relationship between drug use and work as a result of drug-related impairment, many participants identified high-intensity drug use in particular as interfering with their labour market participation.

The interplay between trajectories of drug use and labour market involvement was by no means limited to physical impairment. Drug seeking activities and the avoidance or management of withdrawal produced daily routines that many found inimical to the requirements of being a “nine-to-fiver” (Participant #11, female). One individual described, for example, how gathering empty bottles for recycling was the first activity of her day: “I start binning to make sure that I have enough empties at nine thirty to get my beer” (Respondent #12, female). The economic instability associated with drug seeking was perceived as directly consequential to upholding the expectations of employers. As one participant described:

If you work past a certain hour, you can get the company vehicle, company credit card to get you home, right? I come down to play in the sandbox [drug scene] and get some dope and, you know, I was sick [going through withdrawal]. Cigarettes can contribute to the dope, so I just put [them] on my company card. My boss called me up and said, “It says here there was cigarettes purchased. You remember buying this?” I said, “You know, what? What happened was I paid for the gas but I had a hundred dollar bill and it was three in the morning and they didn’t have change for this thing so I just put it on my company card.” So it sounded believable. They got the tape [video recording] about how it all went down. They said, “we have reason to believe it that didn’t go down that way, so here’s the short: you can resign, and we’ll get you a letter of recommendation because you’re a hell of a tradesman.” I lied, I took a credit card and abused it, there’s no denying that. They gave me a chance to get honest about it, you know, and I chose not to. (Participant #23, male)

In this case, drug seeking behaviour and the avoidance of withdrawal resulted in the inappropriate use of resources, subsequent evasion of responsibility and termination. The need to secure drugs constituted a competing interest that runs counter to the requirements of employment. Multiple participants identified drug access as a critical reason for being unable to undertake employment, as demonstrated by the following participant:

I was a heroin addict and when you’re a heroin addict you can’t make a dentist appointment because you don’t know if you’re going to have heroin that day to go and function. And same for work. You can’t say you’ll be there because you just don’t know. (Participant #21, female)

While drug use significantly interfered with many individuals’ capacity to work, this inability was linked to ongoing drug use as well the capacity to ensure access to drugs, rather than avoid them.

Participants further positioned changes in the intensity or type of drug as strongly influencing long-term trajectories. One individual, for example, identified her initiation into injection drug use as a key change in her personal trajectory that began a chain of events that included losing her job and initiating sex work, which she perceived as significantly impacting her health and capacity to avoid risk and harm.

And it’s a lot of shit, like, I wouldn’t of gotten raped and ended up with HIV. You know what I mean? Like, all these things that wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t of started using. And [my HIV] wasn’t from a needle but it still was, you know, down the long run. Now it’s very hard to crawl out of the hole. (Participant #11, female)

The positioning of her drug use trajectory within a long-term chain of risk points to individuals’ awareness of the accumulation of disadvantage, across which the consequences of drug use can influence pathways in multiple domains. This awareness is consistent with life course approaches emphasizing the importance of transitions and the accumulation of disadvantage over the long term.

Also consistent with these concepts was the identification of the short and long-term health consequences of drug use as disrupting their ability to engage in the labour market. For multiple study participants, their health was “the only thing that impacts if I work or not” (Participant #22, female). Drug-related health concerns included a wide range of conditions, including cirrhosis of the liver, pulmonary diseases such as pneumonia and asthma, as well as infectious diseases commonly attributed to receptive syringe sharing including hepatitis C (HCV) and HIV, infective endocarditis and related complications such as stroke. Some participants described the implications of these drug-related health problems on their daily functionality.

There were times where I just wasn’t physically capable of working and doing the job I do. I mean, I go to work for eight or ten hours, go up and down stairs and ladders and carry materials, working with your hands over your head for hours. So living a lifestyle that’s not healthy, you know, it’s just mentally, physically, it really takes you out of the game. (Participant #5, male)

Others described long term or permanent impacts on their capacity to work.

I also got a bad heart from endocarditis. I’ve got degenerative arthritis in my neck up here. They want to take the vertebrae out which kills the nerves. My arms go numb, I can’t work. If I carry something my arms go numb. I’ll drop it. It sucks. (Participant #16, male)

The treatment of health conditions associated with drug use further had the capacity to operate as a barrier to employment. One respondent noted the potentially debilitating effects of undergoing treatment for HCV:

I had hepatitis and I was sick. I had already been diagnosed but I had no idea that I was really sick. Within a matter of weeks I was on interferon [HCV treatment] and I stayed on interferon for one year and it has an incredible amount of side effects, my hair fell out, I went crazy, and you’re sick, as a dog. With hepatitis [and taking interferon] I didn’t have the stamina to do my nine to five. (Participant #21, female)

Thus, both drug-related health complications and their management often interrupted or changed the course of labour market trajectories.

The influence of labour market (non) participation on drug use

While the experience of a directional relationship linking drug use and associated health conditions to suboptimal employment outcomes was common among participants, the inverse was also reported: suboptimal labour market outcomes also influenced drug use trajectories. Participants connecting non-, un-, or under-employment to drug use often emphasised how employment, as a structured activity, distances individuals from their propensity to use drugs. Discussing her work, one participant who used crack on a daily basis said, “I’m doing something that I like to do and it keeps me busy and it keeps me off other drugs. It’s a good thing to be doing” (Participant #22, female). Another respondent connected his lack of employment as a young man to his long-term pathway: “Yeah I should’ve been kept busy being a young guy and, yeah, I wouldn’t have steered myself the way I went” (Participant #1, male). His attribution of earlier unemployment as a significant determinant of his labour market trajectory is demonstrable of how labour market interruptions at sensitive developmental periods can have significant effects on future outcomes. While others did not link their employment status to their drug use, stating, “I don’t think it matters if I work or not, or if I work a lot, or anything. It’s just how I’m [doing]” (Participant #4, male), a prominent theme in participants’ understanding of the relationship between drug use and work was tied to its ability to shape their daily routines and to provide alternatives to drug use and drug-related activity.

This included spatial considerations where employment was seen as a way of avoiding drug scene involvement. One respondent considered avoiding the local drug scene to be a crucial component of her strategy to not use drugs.

I try and keep myself busy. It’s very hard sometimes, but I know that I have to. Otherwise it’s too easy to just walk down the street and get picked up [by sex work clients] and make money and go use drugs and just get swept right back into that again. (Participant #11, female)

Similarly, the following participant identified access to paid employment as intimately connected to her ability to decrease drug use or maintain abstinence, by distancing her from street-based income generation activities.

I cleaned myself up ‘cause I got really bad into the powder and stuff and I was telling my friend, you know, “I’m just, I’m sick of that life, you know, I’m sick of jumping in garbage bins.” The only way I was gonna maintain straightening out was to have a real job. (Participant #12, female)

Another participant suggested that their work shifts provided a sanctuary, where they were able to avoid using and exposure to periods of heightened drug scene activity.

I do volunteer work. I do 8 hours a week. I don’t use and abuse the place. I use that place for…It’s my safety zone. I won’t go in there drunk, I don’t go in there high. If I wanted to go stay clean for a day or two, I go hang around down there. That’s a useful place. If you believe this, I actually picked a Friday night to be in there volunteering. I’ll tell you why. Because Friday night everyone goes out and parties. (Respondent #13, male)

In the absence of time structure or a means to avoid the local drug scene, individuals’ with a history of high-intensity substance use would have to manage periods of unstructured time that were seen by participants as potentially fostering drug use. Respondent narratives therefore identified work as crucial parts of both achieving and maintaining less harmful drug use patterns.

The reduction of drug use vis-à-vis employment activity was also linked to employment as an inherently meaningful activity.

I want to do something that I get a sense of purpose out of, I don’t wanna just get a paycheck. You know I’d rather just get by and be doing something that I love doing and that I get that sense of purpose from then making a lot of money and being miserable. Or even just making a lot of money and not being miserable but not really feeling like I’m adding anything to life, right? And I believe that that’s an important part of my sobriety that I do that. (Participant #20, male)

The ability of employment to mitigate exposure to drug-scene related risk, structure time or provide meaning was therefore considered an important influence on addiction trajectories, predominantly, though not exclusively, in beneficial ways.

Exogenous influences on drug use and employment

Participants also described circumstances external to both their drug use and labour market pathways that were nevertheless crucially influential on both. A predominant experience was that of a catastrophic event, defined here as a significant and highly stressful life event that was self-described as impacting labour market participation. Such events were reported by 14 of the 22 respondents (63.6%), and generally demarcated a sudden change in individuals’ capacity to work, socio-economic position, social relationships or access to resources. Accidents resulting in significant injury, for example, commonly prompted the initiation or intensification of opiate use as self-medication for pain, as exemplified by the following respondent:

[I was] walking and they hit me twice [with a car]. And then I start using, [thinking I would] only use one time, with the pain and [me] wanting to get good sleep. I got back on welfare, then day after day, month after month and year after year I keep using. If I’m not using, I [would] enjoy going to work, get a family or whatever. People they can come back with injury [after] one year, right? But I got [into an] accident and using, now [it’s] hard to say. (Participant #10, male)

The initiation of heroin use was linked not only to changes in substance use for the self-medication of physical pain. Event-driven emotional distress also impacted individuals’ substance use patterns. The following participant described how her initiation into heroin use coincided with distress from a cancer diagnosis.

And that’s when I found out that I ended up with cancer. Stomach cancer. And the doctor had given me the actual date that I’m supposed to die. That shouldn’t be allowed, and that’s what made me begin to use heroin, was because of that. (Participant #14, female)

Also common among participants were depictions of initiated, re-initiated or intensified use in close succession to the death of a loved one.

I restarted after she died. It’s not even getting high, or forget[ting] or anything, it’s just that you need a break [to] stop my brain. After she died I got wired real quick. It took three days and I got wired again. (Participant #4, male)

The idea that “grief is disabling” (Participant #21, female) was reflected in the comments of individuals who experienced some form of family dissolution, either through relationship failure, divorce, or involuntary separation from children because of lost custody or seizure by government authorities.

As soon as my separation happened I was over with the project. I was so screwed up and depressed and stressed and, you know, my husband ran away with my son. (Participant #14, female)

Study participants demonstrated a clear awareness of the long-term impacts of the events they described. They connected, for example, childhood events with decreased adult functionality.

It’s just I can’t maintain stuff, right? I just can’t. Like, I was abused, horrifically, as a child. And I don’t use that as an excuse but the way it has in the long term affected me is that I just don’t have it within me to be responsible for that long. You know, I can’t explain it. I just know that’s the way it is. (Participant #12, female)

Additionally, individuals noted how long-term consequences of catastrophic events were commonly related to the criminalization of their drug use. These events, beginning with apprehension by police and leading to incarceration or other custodial arrangements within the criminal justice system, interrupted their employment trajectories. They further and indefinitely affected their ability to reengage with the labour market through the acquisition of a criminal record. One participant stated, “Cause of my criminal record you don’t want me. Hire me I might steal something” (Participant #1, male). The considerable and negative potential consequences of labour market interruption and ongoing labour market scarring resulting from criminalization were common. Many participants perceived the catastrophic events they experienced as having significant long-term effects.

Participants repeatedly referred to catastrophic events that adversely affected multiple domains of their lives. These compound events, where, for example, an individual “lost my marriage, got shot and I was in a hospital all in one night” (Participant #17, male) or “lost my daughter, my home, my home-based business all in one day” (Participant #12, female) invariably influenced individuals’ ability to generate income. Any loss in productive capacity would in turn impact their ability to endure catastrophic events.

I got served custody papers one day at work and I came home, and my husband and daughter were gone. Everything was gone. I lost my job. Things went downhill. I lost everything. I was literally more homeless than I was when I first moved onto the streets in Toronto. And so he got custody. (Participant #11, female)

Catastrophic events were positioned by respondents in relation to broader psychological, social, economic, cultural, environmental and structural processes. Regardless of their origin, the consequences of these events were real and often irreversible. These effects involved changes to physical and mental health, the initiation or intensification of drug use, relationship and family composition, the capacity to generate income through incarceration or other negative impacts on labour market and drug use trajectories.

Discussion

Descriptions of the relationship between drug use and labor market trajectories in the current analysis emphasise the complex intermingling of multiple pathways in the production, reproduction and entrenchment of social-, economic-, and health-related vulnerabilities among people who use drugs. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative exploration of the relationship between drug use and labour market trajectories identifying the complex mechanisms linking the two domains, offering an explanatory alternative to deterministic portrayals of the impact of drug use on employment or vice versa. Thematic analyses of individual narratives emphasised three broad themes. First, they identified how drug use interfered with their ability to acquire, maintain, and perform formal employment. Second, respondents focused on how labour market participation had direct bearing on individual drug use patterns, which was for the most part positive. Third, individuals identified external forces that negatively influenced both drug use and labour market trajectories. Exposure to exogenous catastrophic events, in particular, resulted in both considerable reductions in individuals’ perceived and real capacity to participate in the labour market, as well as the initiation or intensification of harmful drug use practices.

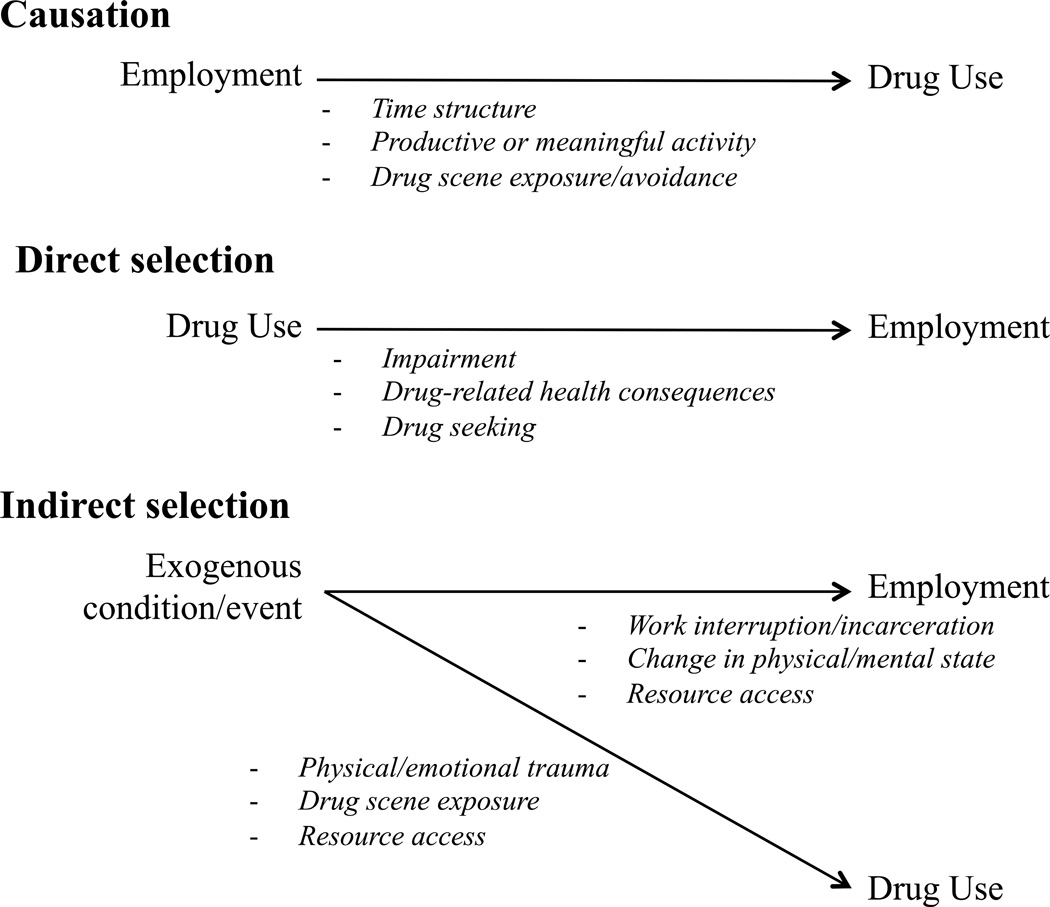

As depicted in Figure 1, these three themes correspond to the theoretical pathways of causation, direct selection and indirect selection at issue in the broader debate surrounding the relationship between employment and health (Bartley et al 2006). Of particular note are the mechanisms specific to each of these patterns. In the case of the direct selection effects of drug use on employment, these include immediate physiological effects, drug-related health outcomes that mediated the relationship between drug use and employment, and drug seeking activities, which often interfered with participants’ ability to reliably fulfill expectations of employer-employee relationships. Additionally, drug-related health conditions may produce acute or chronic illnesses impacting labour market participation that, as in the general population, are significant, negative, and differentially experienced by different demographic groups (Bambra 2011; Ross, & Mirowsky 1995) through their effect on functionality, side effects or treatment burden (Treloar, & Rhodes 2009). The importance of drug seeking behaviour demonstrated in the current study in shaping the daily activity of PWID has been described in earlier research (Preble & Casey 1965; Draus et al 2010). Indeed, drug seeking was described as “work” by many participants, and as something that was time consuming and that structured their daily activities. These results are consistent with longstanding characterisations that the avoidance of withdrawal from opioids in particular leads to drug seeking behavior as a defining characteristic of daily routines and the maintenance of functionality (Draus et al 2010; Lindesmith 1947).

Figure 1.

Theoretical pathways and mechanisms linking labour market and substance use trajectories among people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada

Mechanisms specific to processes of causation that link suboptimal employment to subsequent ill health were also identified in the current study. The presence or absence of time structure, productive or meaningful activity, and drug scene exposure are in line with literature on employment in the general population that points to non-material functions of work that strongly influence health and well-being (Jahoda 1982; Warr 1994). Psychosocial factors identified in this literature, which include time structure, stress, purposeful activity and positive social interactions in the workplace (Cutler 2008; Matthews et al 2010) are important mediating processes linking work and individual drug use trajectories. Additionally, the identification of unemployment as an experience that can be formative to both drug use and labour market trajectories is consistent with research in the general population demonstrating sustained consequences through labour market and health scarring (Hammarström & Janlert 2002; Burgess et al 2003).

Finally, external events, processes or conditions were described as important and often principal drivers of negative transitions in both labour market and drug use trajectories. Participants’ attributions correspond to processes of indirect selection (Bartley et al 2006). Of particular relevance for the majority of participants in the current study was the experience of catastrophic events, described by participants as including accidents and injuries, family breakup, bereavement, loss of child custody, and criminal convictions. The mechanisms connecting catastrophic events to labour market outcomes included displacement, the cutting of social ties, abrupt decreases in access to social, economic, human or other resources, acute emotional trauma or decreased physical capacity. Mechanisms linking these events to drug use trajectories included medication or self-medication for physical or emotional pain management, as well as changes to individual exposure to drugs or drug scenes. Consistent with concepts used in life course approaches to both drug use and employment, these events and their consequences marked transitions in individuals’ ability to participate in the labour market as well as the initiation, re-initiation, or intensification of harmful substances use. While processes of indirect selection have been previously identified among the general population (Bartley et al 2006), the current analysis newly identifies the central role of exogenous events as drivers of indirect selection that negatively impact both labour market and drug use trajectories among PWID.

The narratives of participants further demonstrate that catastrophic events are phenomena where drug use and labour market trajectories intersect. As critical initiation and transitional events among PWID, these catastrophic events were key turning points that are further implicated in processes of accumulation, entrenchment or reinforcement in broader risk trajectories and disadvantage in multiple domains (Ben-Shlomo, & Kuh 2002; Virtanen et al 2005). The findings of the current study therefore underscore how trajectories of disadvantage are analytically inseparable across different domains and can be multiplicative in their effects, shaping opportunities and constraints, conditioning both exposure to risk and the ability to mitigate the impacts of that risk. For example, the health-specific consequences of catastrophic events follow from both proximal, direct health effects from the event itself as well as subsequent, distal health impacts resulting from longer-term changes to socio-economic security and drug use patterns. Following a catastrophic event, the increase in vulnerability to socio-economic marginalization and drug-related harm may be amplified, for example, by increased challenges to meet basic needs, the intensification of drug use and pressure towards engagement in high risk income generating activity such as sex work or drug dealing produced by income scarcity or material insecurity (Debeck et al 2011; DeBeck et al 2007). Over the life course, these burdens may significantly shape prospects for future employment, increase exposures that perpetuate drug use and decrease individuals’ ability to avoid drug-related and other health harm, including HIV infection, extreme violence, treatment failure and death (Shannon et al 2008; Small et al 2013; Richardson et al 2014). Catastrophic events are therefore a juncture characterised by the intersection of multiple trajectories as markers of accumulated disadvantage and critical drivers of health and labour market inequality.

Through its examination of the pathways and associated mechanisms that link drug use and labour market trajectories, the current analysis further suggests intervention strategies that could potentially mitigate the long-term health and labour market impacts of harmful exposures, transitions, and turning points. These findings reinforce previous calls for addiction treatment and harm reduction providers to consider the potential impacts of services on the social and economic functioning of individuals (Richardson et al 2012). Designing and delivering services that facilitate the maintenance or resumption of labour market activity and avoid punitive measures for drug use or relapse are key considerations given the complex interrelationship between drug use and labour market trajectories identified here. Further, a sustained focus on multifaceted supports to facilitate positive labour market involvement may significantly and beneficially alter life course trajectories. These supports could involve different forms of employment protection, the creation of adaptive economic opportunities such as low-threshold employment, the accommodation of episodic labour market absences and increased economic, psychological and social support for individuals who experience catastrophic events. The implications of study findings for public health and related social policy particularly point to multifaceted approaches that recognise the symbiotic benefits of improvements to drug use and labour market outcomes.

Like all qualitative studies, this research is limited by the potential for various forms of response bias, such as recall or social desirability bias (McElrath et al 1994). This may be particularly the case given that participants offered long term retrospective narratives about their drug use and employment histories and that discussions about employment may be accompanied by perceptions that labour market engagement was expected or valued. Findings are also specific to the individuals who participated in the study; others may have different experiences or perspectives. While the current analysis focuses on trajectories along dimensions of drug use and labour market participation, this relationship may be further shaped by factors not examined here. These include, but are not limited to, early experiences of social and economic exclusion such as poverty, homelessness or other features of structural vulnerability such as variations in human capital accumulation, or broader labour market conditions that influence the quality and qualities of drug use and labour market activities. Lastly, individuals were recruited into the study in many cases because of current or past experiences with formal and informal labour market activity that may be atypical among the larger injection drug using population in Vancouver. More research is required to determine if the experiences described here are more broadly applicable to inner-city PWID in this and other contexts.

The current study drew on concepts from life course approaches to explore the relationship between drug use and labour market trajectories among a sample of 22 people who inject drugs. Focused on individuals who were current or recent residents of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, analyses outlining processes of causation, direct selection and indirect selection provide considerable insight into the specific relationship between employment and drug use trajectories. The identification of underlying mechanisms associated with each causal process emphasises the importance of understanding the relationship between drug use and work as complex, multifaceted, and conditioned by the accumulation of risk and disadvantage through mechanism that are endogenous and exogenous to these domains. Of particular note, the importance of catastrophic events as critical to initiation and transitional points linking labour market and drug use trajectories among PWID engenders an approach that considers how cross-domain linkages significantly impact longer chains of risk accumulation and entrenched disadvantage. The subsequent implications of these cross-domain linkages for health and social policy and programmatic interventions emphasise the need to develop multi-faceted approaches that facilitate mutually reinforcing improvements in both drug use and labour market outcomes to reduce labour market and health inequalities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff, including Steve Cain and Caitlin Johnston. The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP–81171) and the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA033147). Lindsey Richardson and Will Small hold Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Awards. Lindsey Richardson is also supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award. At the time the research was conducted Lindsey Richardson held a Doctoral Award from the Pierre Elliot Trudeau Foundation.

Funding Sources:

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP– 81171) and the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA033147). Lindsey Richardson and Will Small hold Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Awards, and Lindsey Richardson is also supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award.

References

- Abell J, Stokoe EH, Billig M. Narrative and the discursive (re)construction of events. In: Andrews M, DAy Sclater S, Squire C, Treacher A, editors. The Uses of Narrative: Explorations in Sociology, Psychology, and Cultural Studies. London: Transaction Publishers; 2004. p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- Anglin MD, Hser Y-I, Grella CE. Drug addiction and treatment careers among clients in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11(4):308–323. [Google Scholar]

- Bambra C. Work, Worklessness, and the Political Economy of Health. Oxford: OUP; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley M. Unemployment and health: selection or causation-a false antithesis? Sociology of Health & Illness. 1988;10(1):41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley M. Unemployment and ill health: understanding the relationship. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1994;48(4):333–337. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.4.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley M, Ferrie J, Montgomery SM. Health and labour market disadvantage: unemployment, non-employment, and job insecurity. In: Wilkinson RG, Marmot MM, editors. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford: OUP; 2006. pp. 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31(2):285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blane D, Smith GD, Bartley M. Social selection: what does it contribute to social class differences in health? Sociology of Health & Illness. 1993;15(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41(5):516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Schonberg J. Righteous Dopefiend. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brethour P. Globe and Mail. 2009. Feb 13, Exclusive demographic picture: A comparison of key statistics in the DTES, Vancouver, B.C. and Canada. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Cagney KA. Neighborhood structural disadvantage, collective efficacy, and self-rated physical health in an urban setting. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43(4):383–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J. Life as narrative. Social Research. 1987;54(1):11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess S, Propper C, Rees H, Shearer A. The class of 1981: the effects of early career unemployment on subsequent unemployment experiences. Labour Economics. 2003;10(3):291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Boyd N, Culbert L. A Thousand Dreams: Vancouver's Downtown Eastside and the Fight for Its Future. Greystone, Toronto: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- City of Vancouver. 2005/06 Downtown Eastside Community Monitoring Report. Vancouver: City of Vancouver; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. 3rd ed. London: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A, Vogl T. NBER working paper 14333. Cambridge, MA: 2008. Socioeconomic status and health: dimensions and mechanisms. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w1433. [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Shannon K, Wood E, Li K, Montaner J, Kerr T. Income generating activities of people who inject drugs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debeck K, Wood E, Qi J, Fu E, McArthur D, Montaner J, Kerr T. Interest in low-threshold employment among people who inject illicit drugs: implications for street disorder. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2011;22(5):376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–1789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draus PJ, Roddy J, Greenwald M. "I always kept a job”: Income generation, heroin use and economic uncertainty in the 21st century Detroit. Journal of Drug Issues. 2010;40(4):841–869. doi: 10.1177/002204261004000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Johnson MK, Crosnoe R. The emergence and development of life course theory. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the Life Course. New York: Springer; 2003. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hammarström A, Janlert U. Early unemployment can contribute to adult health problems: results from a longitudinal study of school leavers. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2002;56(8):624–630. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.8.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heien DM, Pittman DJ. The economic costs of alcohol abuse: an assessment of current methods and estimates. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(6):567–579. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990–2010) Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2011;4(1):4–27. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104010004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Longshore D, Anglin MD. The life course perspective on drug use: a conceptual framework for understanding drug use trajectories. Evaluation Review. 2007;31(6):515–547. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07307316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda M. Employment and Unemployment: A Social-Psychological Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestner R. Illicit drug use and labor market outcomes: a review of economic theory and its empirical implications. Journal of Drug Issues. 1998;28(3):663–680. [Google Scholar]

- Lindesmith AR. Opiate Addiction. Bloomington, IN: Principia Press; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Gallo LC, Taylor SE. Are psychosocial factors mediators of socioeconomic status and health connections? A progress report and blueprint for the future. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:146–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy CB, Comerford M, Metsch LR. Employment among chronic drug users at baseline and 6-month follow-up. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42(7):1055–1067. doi: 10.1080/10826080701409982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough P, Amick BC. The social context of health selection: a longitudinal study of health and employment. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53(1):135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00318-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElrath K, Chitwood DD, Griffin DK, Comerford M. The consistency of self-reported HIV risk behavior among injection drug users. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(12):1965–1970. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Source Book. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- National Drug Intelligence Center. The Economic Impact of Illicit Drug Use on American Society. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ompad DC, Nandi V, Cerdá M, Crawford N, Galea S, Vlahov D. Beyond income: material resources among drug users in economically-disadvantaged New York City neighborhoods. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;120(1–3):127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson G. Deprivation, unemployment and heroin use. In: Dorn N, South N, editors. A Land Fit for Heroin?: Drug Policies, Prevention and Practice. London: MacMillan Education; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Platt JJ. Vocational Rehabilitation of Drug Abusers. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):416–433. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preble E, Casey JJ. Taking care of business-the heroin user's life on the street. Substance Use & Misuse. 1969;4(1):1–24. doi: 10.3109/10826089709027307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Gnam W, Popova S, Baliunas D, Brochu S, Fischer B, Patra J, Sarnocinska-Hart A, Taylor B. The costs of alcohol, illegal drugs, and tobacco in Canada, 2002. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(6):886–895. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter P. Are calculations of the economic costs of drug abuse either possible or useful? Addiction. 1999;94(5):635–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L, Wood E, Montaner J, Kerr T. Addiction treatment-related employment barriers: The impact of methadone maintenance. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;43(3):276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LA, Milloy MJ, Kerr TH, Parashar S, Montaner JS, Wood E. Employment predicts decreased mortality among HIV-seropositive illicit drug users in a setting of universal HIV care. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2014;68(1):93–96. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigg J, Sefton T. Income Dynamics and the Life Cycle. Journal of Social Policy. 2006;35(03):411–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Does employment affect health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(3):230–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(4):911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavelson L. Hooked: Five Addicts Challenge our Misguided Drug Rehab System. New York: The New Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw VN. Substance Use and Abuse: Sociological Perspectives. Praeger, London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and Public Health: Reconceptualizing Disease in Bio-Social Context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2003;17(4):423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Maher L, Lawlor J, Wood E, Shannon K, Kerr T. Injection drug users' involvement in drug dealing in the downtown eastside of Vancouver: social organization and systemic violence. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2013;24(5):479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Rhodes T, Wood E, Kerr T. Public injection settings in Vancouver: physical environment, social context and risk. International Journal on Drug Policy. 2007;18(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HA. Planning, policy and polarisation in Vancouver's downtown eastside. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie. 2003;94(4):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, Cornelisse PGA, Rekart ML, Montaner JSG, Schechter MT, O'Shaughnessy MV. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11(8):F59–F65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Littleton K. Biographies in talk: A narrative-discursive research approach. Qualitative Sociology Review. 2006;2(1):22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Treloar C, Rhodes T. The lived experience of hepatitis C and its treatment among injecting drug users: qualitative synthesis. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19(9):1321–1334. doi: 10.1177/1049732309341656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wel KA. Long-term effects of poor health on employment: the significance of life stage and educational level. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2011;33(7):1096–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr P. A conceptual framework for the study of work and mental health. Work & Stress. 1994;8(2):84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Schachar J, Li K, Stoltz J-A, Shannon K, Miller C, Lloyd-Smith E, Tyndall MW, Kerr T. Sex trade involvement is associated with elevated HIV incidence among injection drug users in Vancouver. Addiction Research & Theory. 2007;15(3):321–325. [Google Scholar]