Abstract

Background

Although modern combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) regimens are better tolerated and less complex than earlier treatments, regimen modification or discontinuation remains a concern.

Methods

We studied HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) participants who initiated first or second cART regimens during: 1996–1999, 2000–2003, 2004–2007 and 2008–2011. We analyzed regimen durability (time to regimen modification) and success (achieving undetectable plasma HIV RNA) for first and second cART regimens using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests, and examined factors associated with durability and success of first cART regimen using proportional hazards models.

Results

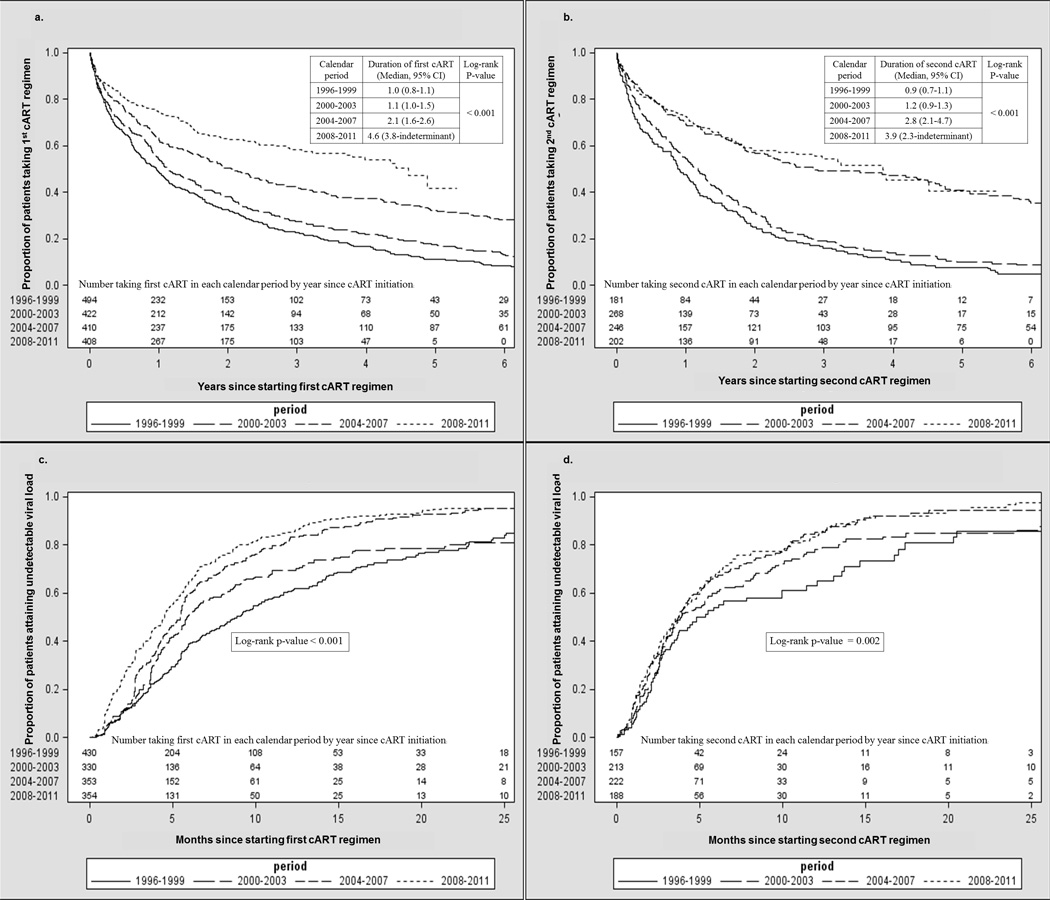

Durability of cART was progressively longer for cART regimens initiated in more recent periods: median first cART regimen durations were 1.0, 1.1, 2.1 and 4.6 years in 1996–1999, 2000–2003, 2004–2007 and 2008–2011, and median second cART durations were 0.9, 1.2, 2.8 and 3.9 years, respectively (both p<0.001). Comparing 1996–1999 and 2008–2011, the percentage of patients who achieved an undetectable HIV RNA within 6 months of first cART initiation increased from 65% to 81%, and from 63% to 80% on second cART (both p<0.001). Among patients initiating first cART during 2008–2011, black non-Hispanic/Latino race/ethnicity and ≥twice daily dosing were significantly associated with higher rates of regimen modification (p<0.05), and higher baseline HIV RNA levels were associated with failure to achieve an undetectable HIV RNA (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Among HIV-infected U.S. adults in routine HIV care, durability of first and second cART regimens and the likelihood of prompt virologic suppression increased during 1996–2011, coincident with the availability of more tolerable, less complex cART options.

Keywords: Antiretroviral therapy, durability, cohort study

Introduction

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has resulted in marked and sustained reductions in morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected persons.1 Although newer drug combinations allow for reduced pill burden and improved toxicity profiles, remaining concerns that may account for regimen discontinuation or modification include drug resistance, tolerability, regimen complexity, financial cost, and concerns over potential medication interactions. The risk of cART treatment failure decreases with increased duration of HIV RNA suppression and increases with successive cART regimens.2,3 Maximizing the durability of first and subsequent effective cART regimens remains crucial for optimizing long-term management for HIV-infected patients.

Reports from U.S. studies early in the cART era indicated that initial cART regimen duration ranged from a median of 11.8 months to 2.8 years, depending on year of treatment initiation.2,4–7 Previously, we reported that patients in the HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) seen in 1994–2002 received a mean 1.8 cART regimens per person over a 39-month follow-up period and spent progressively less time on subsequent regimens.2 Factors associated with shorter duration of initial regimens included not receiving a protease inhibitor-(PI) containing regimen and higher baseline HIV RNA levels (>100,000 copies/mL). A single-center study of HIV-infected patients initiating cART in 2000–2007 indicated that the median duration of first cART lengthened from about 2.1 years to 2.9 years after the introduction of once-daily, fixed-dose combination regimens in 2004,5 suggesting improved regimen durability as a result of regimen simplification. A recent analysis of data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study found that median duration of first cART regimens for antiretroviral-naïve men initiating cART in 2006–2009 was over 3 years, a substantial improvement since earlier years.7

We examined how cART regimen use, duration, and factors associated with regimen modification have evolved in the HOPS during 1996–2011. Given changing trends in antiretroviral toxicities, regimen complexity, and resultant challenges in medication adherence,8–10 we sought to determine whether regimen duration and rates of virologic suppression have increased over this 15-year period among patients who initiated first and/or second cART regimens.

Methods

The HIV Outpatient Study

The HOPS is an ongoing, prospective observational cohort study that has continuously recruited and followed HIV-infected patients since 1993. In the timeframe of this analysis, study sites included 12 clinics (6 university, 4 public, and 2 private) in eight U.S. cities, with a total enrollment of over 10,000 patients (approximately 2,500 actively seen in any given year). We analyzed data from HOPS participants seen at clinic sites located in: Tampa, FL (2 sites); Washington, DC; Denver, CO (2 sites); Chicago, IL (2 sites); Portland, OR; Walnut Creek, CA; Oakland, CA; Stony Brook, NY; and Philadelphia, PA. HOPS clinicians have extensive experience treating HIV-infected patients. The study protocol is approved and renewed annually by each participating institution's ethical review board. All study participants provide written, informed consent.

Trained staff at each site abstract outpatient medical record information, electronically enter these data, and submit them to the data management center to be compiled centrally, reviewed and edited before analysis. Abstracted information includes demographic characteristics and risk factors for HIV infection; diagnoses; prescribed medications, including dose and duration; laboratory values, including CD4+ cell counts and plasma HIV RNA levels (viral loads); causes of mortality and hospitalizations; and primary medical care payment source.

Study population

We limited analysis to patients who were ART-naïve before starting their first cART regimen, had complete documentation of ART history, and initiated either first or second cART regimen during one of four calendar periods: 1996–1999, 2000–2003, 2004–2007 or 2008–2011 while under the observation in the HOPS. We used the HOPS dataset updated as of 31 December 2013; data from patients receiving ongoing cART regimens were censored for analysis on 30 June 2013 to allow for lag in data entry. In this way, we ensured that patients who initiated cART through the end of 2011 had an opportunity to be observed while receiving cART for at least one year.

Definitions of predictor and outcome variables

For this analysis, we defined cART as three or more antiretroviral drugs. “Baseline” was defined as the date of first or second cART regimen initiation, as appropriate. Baseline viral load and CD4+ cell counts were measurements obtained closest to cART regimen start, and within 183 days before and up to 7 days after regimen start. We analyzed two outcomes: cART regimen modification and virologic suppression after baseline. Regimen modification was defined as a change in at least one antiretroviral drug in the regimen not including dose changes, switches to a fixed dose combination of the same drugs, or switches between lamivudine and emtricitabine, and could include regimen discontinuation (temporary or permanent) defined as discontinuation of all drugs in the regimen for at least 14 days. Since discontinuations accounted for a minority of such events, we henceforth refer to regimen modification as encompassing modification/discontinuation. We characterized first cART regimens by whether they contained non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), low-dose ritonavir (RTV)-boosted or non-boosted PIs, or integrase or entry inhibitors, creating exclusive categories in the following order: NNRTI, integrase or entry inhibitor, RTV-boosted PI, and non-boosted PI. Virologic suppression was defined as achieving an undetectable plasma HIV viral load (per manufacturer’s assay-specific lower limit of detection cut-off), and calculated for HIV viral load tests with lower limit of detection < 400 copies/mL (n=1,652 or 15% of viral load measurements using assays with a lower limit of detection of 400 copies/mL or higher in earlier calendar years were excluded from analysis).

Statistical analyses

To compare distinct subgroups of patients across the four calendar periods, we used a likelihood ratio chi-square or a Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test. For treatment-naïve persons who initiated first cART regimen during one of the calendar periods (1996–1999, 2000–2003, 2004–2007, and 2008–2011), we used Kaplan-Meier survival curves that incorporate the censoring to estimate time to regimen modification and time to virologic suppression, and log-rank tests to compare curves among calendar periods. We similarly analyzed cART treatment-experienced persons who initiated second cART regimen during these periods. Because some patients were included in both the first and second cART regimen analyses (see Results for details), outcomes for first and second regimen durations for these patients are correlated; thus, first versus second regimen durations for the same calendar period were not directly compared statistically in our analysis. Furthermore, for treatment-naïve patients who initiated first cART regimens, we used multivariable proportional hazards regression models to identify factors independently associated with regimen modification and with virologic suppression for regimens initiated in each calendar period. We adjusted for sociodemographic variables (e.g., sex, race/ethnicity, insurance) and HIV-related measures (e.g., baseline CD4+ cell count, class of cART regimen) that we considered as potentially associated with achieving a more durable response and virologic suppression while on cART. All variables were included in each of the models regardless of significance, with the exception of variables that were not relevant in the time period of interest, i.e., integrase/entry inhibitor use prior to 2008. In the analysis of time to virologic suppression, for patients with missing baseline viral load values we used the Markov chain Monte Carlo method for multiple imputations11,12 to estimate baseline viral loads using demographic and baseline CD4+ cell count data. This process involves using information from patients with known baseline viral loads to estimate baseline viral loads for patients with unknown information. Assuming that patients with similar baseline CD4+ cell counts and demographic characteristics are also likely to have similar baseline viral loads, we created new data sets that included baseline viral load information statistically “imputed” for patients previously missing these data. Five imputations, the default quantity, were created by the statistical software. The results of the five analyses were then combined to obtain a measure of the error produced by this imputation process. Statistical analyses were done using SAS v9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Among 8,910 HOPS patients with ≥2 visits during 1996–2011, we identified 1,734 patients who met inclusion criteria for first cART regimen analyses; we excluded 6,827 patients who were ART-experienced at start of HOPS observation or before 1996, 204 patients with an incomplete ART history recorded, and 145 patients who initiated cART after 2011 (i.e., outside of the timeframe for this analysis).

In a separate selection process, among 3,068 HOPS patients with ≥2 visits during 1996–2011, complete ART histories, and whose only antiretroviral experience was a single cART regimen (initiated before or after start of HOPS observation), we identified 897 patients meeting inclusion criteria for second cART regimen analyses; we excluded 2,104 patients who did not start a second cART regimen during HOPS observation, and 67 who started second cART after 2011 (i.e., outside of the timeframe for this analysis).

Thus we analyzed 1,734 persons who initiated first cART regimens (494 in 1996–1999, 422 in 2000–2003, 410 in 2004–2007, and 408 in 2008–2011) and 897 who initiated second cART regimens (181 in 1996–1999, 268 in 2000–2003, 246 in 2004–2007, and 202 during 2008–2011) during the study period. Of the 897 patients included in the analysis of second cART, 579 were included in the analyses of first cART (122 in 1996–1999, 149 in 2000–2003, 172 in 2004–2007, and 136 in 2008–2011). Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients starting first and second cART regimens are shown in Table 1. Of the 1,734 and 897 who initiated first and second cART regimens, there were 212 (12.2%) and 30 (3.3%), respectively, with no pre-cART viral load recorded whose values were therefore imputed.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients initiating first and second cART, the HIV Outpatient Study, 1996–2011.

| Initiating first cART regimen | Initiating second cART regimen | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristics | Overall | 1996–1999 | 2000–2003 | 2004–2007 | 2008–2011 | p- | Overall | 1996–1999 | 2000–2003 | 2004–2007 | 2008–2011 | p- |

| Number(%) or median (IQR) | (n=1,734) | (n=494) | (n=422) | (n=410) | (n=408) | value* | (n=897) | (n=181) | (n=268) | (n=246) | (n=202) | value* |

| Age, years | 38 (31–45) | 36 (32–43) | 38 (32–44) | 38 (31–46) | 40 (90–47) | 0.004 | 40 (34–47) | 38 (34–45) | 40 (34–45) | 40 (34–47) | 44 (36–51) | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 1,330 (76.7) | 393 (79.6) | 297 (70.4) | 320 (78.1) | 320 (78.4) | 0.006 | 735 (81.9) | 157 (86.7) | 218 (81.3) | 208 (84.6) | 152 (75.3) | 0.019 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.001 | 0.33 | ||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic/Latino | 767 (44.2) | 258 (52.2) | 165 (39.1) | 185 (45.1) | 159 (39.0) | 452 (50.4) | 89 (49.2) | 136 (50.8) | 133 (54.1) | 94 (46.5) | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic/Latino | 672 (38.8) | 162 (32.8) | 181 (42.9) | 151 (36.8) | 178 (43.6) | 309 (34.5) | 70 (38.7) | 93 (34.7) | 74 (30.1) | 72 (35.6) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 223 (12.9) | 54 (10.9) | 58 (13.7) | 52 (12.7) | 59 (14.5) | 110 (12.3) | 19 (10.5) | 34 (12.7) | 32 (13.0) | 25 (12.4) | ||

| Other race/ethnicity | 72 (4.2) | 20 (4.1) | 18 (4.3) | 22 (5.4) | 12 (2.9) | 26 (2.9) | 3 (1.7) | 5 (1.9) | 7 (2.9) | 11 (5.5) | ||

| HIV transmission risk category | < 0.001 | 0.54 | ||||||||||

| Men who have sex with men | 923 (53.2) | 281 (56.9) | 184 (43.6) | 225 (54.9) | 233 (57.1) | 531 (59.2) | 104 (57.5) | 161 (60.1) | 157 (63.8) | 109 (54.0) | ||

| Heterosexual sex | 571 (32.9) | 146 (29.6) | 170 (40.3) | 125 (30.5) | 130 (31.9) | 258 (28.8) | 52 (28.7) | 77 (28.7) | 64 (26.0) | 65 (32.2) | ||

| Intravenous drug use | 123 (7.1) | 45 (9.1) | 35 (8.3) | 28 (6.8) | 15 (3.7) | 56 (6.2) | 16 (8.8) | 16 (6.0) | 12 (4.9) | 12 (5.9) | ||

| Other/unknown | 117 (6.8) | 22 (4.5) | 33 (7.8) | 32 (7.8) | 30 (7.4) | 52 (5.8) | 9 (5.0) | 14 (5.2) | 13 (5.3) | 16 (7.9) | ||

| Insurance | 0.011 | 0.07 | ||||||||||

| Private | 919 (53.0) | 276 (55.9) | 206 (48.8) | 240 (58.5) | 197 (48.3) | 590 (65.8) | 122 (67.4) | 173 (64.6) | 177 (72.0) | 118 (58.4) | ||

| Public | 533 (30.7) | 135 (27.3) | 141 (33.4) | 120 (29.3) | 137 (33.6) | 223 (24.9) | 44 (24.3) | 68 (25.4) | 46 (18.7) | 65 (32.2) | ||

| Other/unknown | 282 (16.3) | 83 (16.8) | 75 (17.8) | 50 (12.2) | 74 (18.1) | 84 (9.4) | 15 (8.3) | 27 (10.1) | 23 (9.4) | 19 (9.4) | ||

| HIV viral load, log10 c/mL | 4.8 (4.2–5.3) | 4.7 (4.2–5.3) | 4.8 (4.3–5.4) | 5.0 (4.5–5.4) | 4.5 (4.0–5.0) | 0.002 | 2.0 (1.4–3.5) | 3.0 (1.9–4.4) | 2.3 (1.4–3.6) | 1.6 (1.4–3.0) | 1.7 (1.4–2.6) | < 0.001 |

| CD4+ count, cells/mm3 | 260 (102–407) | 262 (98–458) | 220 (53–379) | 246 (103–349) | 318 (186–440) | 0.010 | 397 (219–639) | 294 (150–552) | 409 (232–668) | 380 (237–596) | 480 (284–728) | < 0.001 |

| Regimen dosing | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Once daily | 607 (35.0) | 0 (0.0) | 56 (13.3) | 256 (62.4) | 295 (72.3) | 412 (45.9) | 20 (11.1) | 77 (28.7) | 187 (76.0) | 128 (63.4) | ||

| Twice daily | 867 (50.0) | 249 (50.4) | 353 (83.7) | 153 (37.3) | 112 (27.5) | 436 (48.6) | 117 (64.6) | 187 (69.8) | 59 (24.0) | 73 (36.1) | ||

| Thrice daily | 260 (15.0) | 245 (49.6) | 13 (3.1) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 49 (5.5) | 44 (24.3) | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| cART regimen components | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| NNRTI | 676 (39.0) | 120 (24.3) | 206 (48.8) | 175 (42.7) | 175 (42.9) | 335 (37.4) | 55 (30.4) | 124 (46.3) | 110 (44.7) | 46 (22.8) | ||

| NRTI's only | 55 (3.2) | 11 (2.2) | 40 (9.5) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (3.0) | 2 (1.1) | 23 (8.6) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| PI and NNRTI | 51 (5.9) | 26 (5.3) | 15 (3.6) | 8 (2.0) | 2 (0.5) | 52 (5.8) | 21 (11.6) | 18 (6.7) | 7 (2.9) | 6 (3.0) | ||

| Boosted PI | 401 (23.1) | 12 (2.4) | 73 (17.3) | 198 (48.3) | 118 (28.9) | 212 (23.6) | 4 (2.2) | 56 (20.9) | 95 (38.6) | 57 (28.2) | ||

| Non-boosted PI | 452 (26.1) | 325 (65.8) | 88 (20.9) | 24 (5.9) | 15 (3.7) | 190 (21.2) | 99 (54.7) | 47 (17.5) | 31 (12.6) | 13 (6.4) | ||

| Integrase or entry inhibitor | 99 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 98 (24.0) | 81 (9.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 79 (39.1) | ||

| ZDV or d4T-containing cART | 892 (51.4) | 478 (96.8) | 328 (77.7) | 76 (18.5) | 10 (2.5) | < 0.001 | 421 (46.9) | 167 (92.3) | 193 (72.0) | 47 (19.1) | 14 (6.9) | < 0.001 |

| ABC or TDF-containing cART | 908 (52.4) | 20 (4.1) | 161 (38.2) | 334 (81.5) | 393 (96.3) | < 0.001 | 559 (62.3) | 20 (11.1) | 122 (45.5) | 224 (91.1) | 193 (95.5) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; c/mL, copies per milliliter; IQR, interquartile range; NNRTI, non-nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; ZDV, zidovudine; d4T, stavudine; ABC, abacavir; TDF, tenofovir disoproxyl fumarate

Jonckheere-Terpstra test of trend from earlier to later time periods or likelihood ratio chi-square test

Among first cART initiators, median age was 38 years (interquartile range [IQR] 31–45), and the majority were male (77%), many were white non-Hispanic/Latino (44%), in the risk group of men who have sex with men (MSM) (53%), and had private insurance (53%). Among patients who initiated second cART, median age was 40 years (IQR 34–47), and the majority were male (82%), white non-Hispanic/Latino (50%), MSM (59%), and had private insurance (66%). Most demographic characteristics did significantly change over time among patients who initiated first cART: median age increased slightly, the percentage of black non-Hispanic/Latinos and Hispanic/Latinos increased, and the percentage who reported a history of injection drug use (IDU) or who received cART regimens dosed more often than once daily decreased across the calendar periods; for second cART, median age increased, and the proportion who reported a history of injection drug use (IDU) or who received cART regimens dosed more often than once daily decreased across the calendar periods (see Table 1). These demographic trends were comparable to those observed across these calendar periods in the overall HOPS cohort (data not shown).13,14

Among first cART initiators, median baseline plasma viral load was 4.8 log10 copies/mL (IQR 4.2–5.3) and median baseline CD4+ cell count was 260 cells/mm3 (IQR 102–407); median baseline viral load decreased among patients initiating cART over the four calendar periods, ranging from 4.7 to 4.5 log10 copies/mL (p=0.002 for trend), and median CD4+ cell count increased over time from 262 to 318 cells/mm3 (p=0.001 for trend). For second cART initiators, median baseline plasma viral load was 2.0 log10 copies/mL (IQR 1.4–3.5) and median baseline CD4+ cell count was 397 cells/mm3 (IQR 219–639); median baseline viral load was progressively lower over the four calendar periods, ranging from 3.0 to 1.7 log10 copies/mL, and median CD4+ cell count increased over time from 294 to 480 cells/mm3 (both p<0.001).

The most commonly prescribed first cART regimens included a non-boosted PI in calendar period 1996–1999, an NNRTI cART in 2000–2003 and 2008–2011, and a RTV-boosted-PI in 2004–2007 (Table 1). Second cART regimen types were most likely to include a non-boosted PI in 1996–1999, and an NNRTI in 2000–2003 and 2004–2007, and an integrase or entry inhibitor in 2008–2011. Over time, the daily dosing frequency of first and second cART diminished; for example, 50% of first cART regimens were dosed three times daily in 1996–1999 compared with less than 1% in 2008–2011. First and second cART regimens were more likely to involve once daily dosing in more recent periods (p<0.001). Among regimens prescribed during 2008–2011, 72% of first cART and 63% of second cART were once-daily regimens.

cART regimen duration and success

Combination ART regimens were modified for 1,231 (71%) of 1,734 patients initiating a first cART regimen and 641 (71%) of 897 patients initiating a second cART regimen; observation time was censored for the remaining patients who continued cART regimens past the end of the follow-up period (Table 2). These regimen modifications included 318 regimen discontinuations (of at least 2 weeks) for first cART regimens and 109 regimen discontinuations for second cART regimens. Estimated median durations of first and second cART regimens were 1.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.4–1.7) and 1.6 (95% CI 1.4–1.8) years, respectively, and each increased significantly across calendar periods (Figures 1a and 1b, p<0.001). Median first cART regimen durations increased over calendar time; they were 1.0 (95% CI 0.8–1.1), 1.1 (95% CI 1.0–1.5), 2.1 (95% CI 1.6–2.6), and 4.6 (3.8- indeterminate upper confidence limit) years for regimens initiated in 1996–1999, 2000–2003, 2004–2007, and 2008–2011, respectively. The percentage of patients remaining on first cART regimens at 24 months after initiation was 45% overall; this percentage was 32%, 38%, 51%, and 63%, respectively, for patients starting first cART during each of the four calendar periods (Table 2). Median second cART regimen durations also increased over calendar time; they were 0.9 (95% CI 0.7–1.1), 1.2 (95% CI 0.9–1.3), 2.8 (95% CI 2.1–4.7) and 3.9 (95% CI 2.3–indeterminate upper confidence limit) years, respectively. The percentage of patients remaining on second cART regimens at 24 months after initiation was 43% overall, and 25%, 31%, 57%, and 58%, respectively, for the four calendar periods (Table 2).

Table 2.

First and second cART regimen modifications and discontinuations by calendar period of regimen initiation, the HIV Outpatient Study, 1996–2011.

| First cART regimen | Second cART regimen | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall (n=1,734) |

1996–1999 (n=494) |

2000–2003 (n=422) |

2004–2007 (n=410) |

2008–2011 (n=408) |

p- value*** |

Overall (n=897) |

1996–1999 (n=181) |

2000–2003 (n=268) |

2004–2007 (n=246) |

2008–2011 (n=202) |

p- value*** |

| Observed to modify/discontinue cART regimen, n (%)* |

1,231 (71.0) | 453 (91.7) | 349 (82.7) | 271 (66.1) | 158 (38.7) | < 0.001 | 641 (71.5) | 170 (93.9) | 232 (86.6) | 149 (60.6) | 90 (44.6) | < 0.001 |

| Without recorded viral load | 306 (24.9) | 105 (23.2) | 82 (23.5) | 64 (23.6) | 55 (34.8) | 164 (25.6) | 49 (28.8) | 50 (21.6) | 31 (20.8) | 34 (37.8) | ||

| With undetectable viral load at last measurement |

521 (42.3) | 188 (41.5) | 142 (40.7) | 133 (49.1) | 58 (36.7) | 286 (44.6) | 65 (38.2) | 101 (43.5) | 78 (52.4) | 42 (46.7) | 0.002 | |

| With detectable viral load at last measurement |

404 (32.8) | 160 (35.3) | 125 (35.8) | 74 (27.3) | 45 (28.5) | 0.11 | 191 (29.8) | 56 (32.9) | 81 (34.9) | 40 (26.9) | 14 (15.6) | |

| Pre-cART viral load, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| No pre-cART viral load recorded | 212 (12.2) | 76 (15.4) | 64 (15.2) | 39 (9.5) | 33 (8.1) | 30 (3.3) | 8 (4.4) | 8 (3.0) | 7 (2.9) | 7 (3.5) | ||

| Pre-cART viral load ≤1000 c/mL | 55 (3.2) | 8 (1.6) | 21 (5.0) | 7 (1.7) | 19 (4.7) | 594 (66.2) | 86 (47.5) | 176 (65.7) | 179 (72.8) | 153 (75.7) | < 0.001 | |

| Pre-cART viral load >1000 c/mL | 1,467 (84.6) | 410 (83.0) | 337 (79.9) | 364 (88.8) | 356 (87.3) | 0.16 | 273 (30.4) | 87 (48.1) | 84 (31.3) | 60 (24.4) | 42 (20.8) | |

| Remained on cART regimen at 6m** | 72.3 (70.1–74.3) | 65.4 (61.0–69.5) | 68.8 (64.1–73.0) | 75.6 (71.1–79.5) | 81.0 (76.8–84.5) | < 0.001 | 73.6 (70.5–76.4) | 63.1 (55.5–69.7) | 69.3 (63.3–74.5) | 80.8 (75.2–85.3) | 80.1 (73.8–85.0) | < 0.001 |

| Remained on cART regimen at 12m** | 59.2 (56.8–61.5) | 48.5 (44.0–52.9) | 54.0 (49.1–58.7) | 62.7 (57.8–67.3) | 74.6 (69.9–78.6) | < 0.001 | 61.3 (58.0–64.4) | 47.8 (40.3–54.9) | 54.9 (48.6–60.7) | 69.0 (62.6–74.5) | 72.8 (66.0–78.4) | < 0.001 |

| Remained on cART regimen at 24m** | 44.9 (42.5–47.3) | 32.5 (28.3–36.7) | 38.0 (33.3–42.8) | 50.5 (45.4–55.4) | 63.1 (58.0–67.9) | < 0.001 | 42.8 (39.4–46.1) | 25.0 (18.9–31.6) | 31.3 (25.6–37.1) | 56.7 (50.0–62.9) | 58.1 (50.6–64.8) | < 0.001 |

| Viral load undetectable by 6m of cART initiation** |

53.5 (50.6–56.4) | 38.8 (33.6–44.5) | 51.2 (45.1–57.7) | 59.8 (54.2–65.5) | 64.6 (59.2–70.1) | < 0.001 | 63.1 (59.3–67.0) | 53.9 (44.6–63.8) | 60.1 (52.7–67.6) | 66.9 (60.1–73.5) | 67.9 (60.5–75.1) | 0.002 |

| Viral load undetectable by 12m of cART initiation** |

74.6 (71.9–77.2) | 60.7 (54.9–66.5) | 69.5 (63.4–75.5) | 81.9 (77.0–86.3) | 85.4 (81.1–89.3) | < 0.001 | 79.7 (76.1–83.0) | 61.3 (51.4–71.3) | 78.1 (70.7–84.7) | 85.4 (79.5–90.3) | 83.5 (76.9–89.0) | 0.002 |

| Viral load undetectable by 6m of cART initiation, among those with baseline viral load >1,000 c/mL** |

55.4 (52.3–58.5) | 41.3 (35.6–47.5) | 54.9 (48.0–62.0) | 61.2 (55.4–67.2) | 64.3 (58.6–70.1) | < 0.001 | 44.0 (36.2–52.7) | 32.6 (20.0–50.2) | 35.4 (23.3–51.4) | 48.9 (33.8–66.5) | 66.9 (49.0–83.8) | < 0.001 |

| Viral load undetectable by 12m of cART initiation, among those with baseline viral load >1,000 c/mL** |

77.6 (74.8–80.3) | 63.3 (57.2–69.5) | 74.8 (68.2–81.0) | 84.4 (79.4–88.7) | 86.5 (81.9–90.4) | < 0.001 | 61.7 (52.7–70.8) | 42.6 (26.8–62.6) | 58.5 (41.9–75.9) | 69.8 (53.2–84.9) | 79.3 (62.0–92.3) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; c/mL, copies per milliliter; CI, confidence interval; m, months. Note: Only viral load tests with lower limit of detection < 400 copies/ml are included in estimates of time to reach viral load goal

Percentage of patients observed to discontinue cART regimen as of December 31, 2013 (the remainder of patients remained on regimen and their observation was censored)

%, 95% confidence interval, based on the Kaplan-Meier estimate; p-value represents log-rank p-value

p-value represents test of trend except where noted

Figure 1.

Years to first (a) and second (b) regimen discontinuation and months to attaining undetectable viral load for first (c) and second (d) cART regimen, by cART initiation calendar period (Kaplan-Meier curves), the HIV Outpatient Study, 1996–2011. Baseline characteristics listed in the table were included in all models except where noted.

The percentage of patients who achieved virologic suppression within 6 months of cART initiation significantly increased over the four calendar periods, from 65% to 81% for first cART, and from 63% to 80% for second cART (Figures 1c and 1d, p<0.001 for each). Among patients with baseline HIV viral loads >1,000 copies/mL, the percentage who achieved virologic suppression within 6 months of regimen initiation also increased over time, from 41% to 64% on first cART (p<0.001) and from 33% to 67% on the second cART (p<0.001).

Factors associated with first cART regimen duration and success

For first cART regimens initiated during the first calendar period (1996–1999), factors independently associated with higher rates of regimen modification were: being of black non-Hispanic/Latino race/ethnicity, having public or no insurance, having a baseline CD4+ cell count < 200 cells/mm3, and receiving non-boosted PI-containing regimens (adjusted hazard ratios [aHRs] 1.30, 1.32, 1.25, and 1.27, respectively, Table 3). For first cART regimens initiated during 2000–2003, twice or more daily dosing was associated with higher rates of first cART modification (aHR 1.50). For first cART regimens initiated during 2004–2007, age < 40 years (aHR 1.35, 95% CI 1.05–1.73), IDU HIV transmission risk, twice or more daily dosing, and receiving a regimen containing RTV-boosted PI were associated with higher rates of first cART modification (aHRs 1.35, 1.59, 1.58, and 1.57, respectively). For first cART regimens initiated during 2008–2011, black non-Hispanic/Latino race/ethnicity (aHR 1.64) and twice or more daily dosing (aHR 1.72) were associated with higher rates of first cART modification.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models by calendar period of cART initiation for factors associated with time to first cART regimen modification/discontinuation, the HIV Outpatient Study, 1996–2011 (N = 1,734; n = 1,231 [71%] observed to discontinue first ART regimen during follow-up period). Baseline characteristics listed in the table were included in all models except where noted.

| Calendar period of first cART initiation Number observed to modify/discontinue first cART regimen (%) |

1996–1999, N = 494 n = 453 (91.7%) |

2000–2003, N = 422 n = 349 (82.7%) |

2004–2007, N = 410 n = 271 (66.1%) |

2008–2011, N = 408 n = 158 (38.7%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristic | aHR (95% CI) | p-value | aHR (95% CI) | p-value | aHR (95% CI) | p-value | aHR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Age in years < 40 (vs. ≥ 40 years) | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) | 0.15 | 0.99 (0.79–1.23) | 0.91 | 1.35 (1.05–1.73) | 0.020 | 1.07 (0.78–1.47) | 0.69 |

| Female sex (vs. male sex) | 0.92 (0.71–1.18) | 0.50 | 1.02 (0.80–1.30) | 0.89 | 1.06 (0.77–1.48) | 0.71 | 1.27 (0.86–1.87) | 0.23 |

| Black, non-Hispanic/Latino race/ethnicity (vs. other race/ethnicities) | 1.30 (1.06–1.60) | 0.012 | 1.25 (0.99–1.58) | 0.06 | 1.31 (0.99–1.72) | 0.06 | 1.64 (1.16–2.33) | 0.006 |

| IDU HIV transmission risk (vs. other HIV transmission risks) | 1.08 (0.78–1.49) | 0.66 | 1.00 (0.67–1.50) | 0.99 | 1.59 (1.01–2.52) | 0.047 | 0.97 (0.39–2.43) | 0.95 |

| Public/no insurance (vs. private insurance) | 1.32 (1.08–1.62) | 0.007 | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.33 | 0.95 (0.72–1.26) | 0.72 | 0.82 (0.57–1.17) | 0.28 |

| Baseline CD4+ cell count < 200 cells/mm3 (vs. ≥ 200 cells/mm3) | 1.25 (1.03–1.51) | 0.022 | 1.10 (0.89–1.37) | 0.38 | 0.78 (0.61–1.01) | 0.06 | 0.81 (0.58–1.14) | 0.23 |

| Twice or more daily dosing (vs. once daily dosing) | n/a | 1.50 (1.07–2.10) | 0.020 | 1.58 (1.21–2.06) | < 0.001 | 1.72 (1.05–2.81) | 0.032 | |

| Boosted PI-containing cART (vs. NNRTI cART) | 1.01 (0.55–1.85) | 0.97 | 1.22 (0.91–1.63) | 0.19 | 1.57 (1.19–2.08) | 0.002 | 1.40 (0.96–2.05) | 0.08 |

| Unboosted PI-containing cART (vs. NNRTI cART) | 1.27 (1.03–1.56) | 0.026 | 1.23 (0.94–1.62) | 0.13 | 1.12 (0.65–1.92) | 0.69 | 1.38 (0.59–3.24) | 0.46 |

| Integrase or entry inhibitor-containing cART (vs. NNRTI cART) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.56 (0.30–1.02) | 0.06 | |||

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; IDU, injection drug use; PI, protease inhibitor, NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; n/a, not applicable (variable not included in the model because not relevant in the specific calendar period of interest).

For first cART regimens initiated during 1996–1999, factors independently associated with lower rates of achieving virologic suppression included IDU HIV transmission risk (aHR 0.32), and having public or no insurance (aHR 0.66, Table 4). For first cART regimens initiated during 2000–2003, black non-Hispanic/Latino race/ethnicity was associated with not achieving virologic suppression (aHR 0.57). For first cART regimens initiated during 2004–2007, black non-Hispanic/Latino race/ethnicity, higher baseline viral load (per log10 copies/mL increase), twice or more daily dosing, and receiving non-boosted PI-containing regimens were associated with not achieving virologic suppression (aHR 0.69, 0.75 per 1 log10 copies/mL, 0.71, and 0.46, respectively). For first cART regimens initiated during 2008–2011, higher baseline viral load was associated with not achieving virologic suppression (aHR 0.73 per 1 log10 copies/mL).

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models by calendar period of cART initiation for factors associated with achieving an undetectable HIV viral load test result* with the first cART regimen, the HIV Outpatient Study, 1996–2011 (N = 1,467; n = 996 [66%] achieved an undetectable viral load with the first cART regimen). Baseline characteristics listed in the table were included in all models except where noted.

| Calendar period of first cART initiation Number achieving undetectable viral load with first cART (%) |

1996–1999, N = 430 n = 227 (52.8%) |

2000–2003, N = 330 n = 190 (57.6%) |

2004–2007, N = 353 n = 265 (75.1%) |

2008–2011, N = 354 n = 284 (80.2%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristic | aHR (95% CI) | p-value | aHR (95% CI) | p-value | aHR (95% CI) | p-value | aHR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Age in years < 40 (vs. ≥ 40 years) | 0.86 (0.65–1.12) | 0.26 | 0.98 (0.73–1.33) | 0.90 | 1.01 (0.79–1.31) | 0.92 | 1.05 (0.82–1.33) | 0.72 |

| Female sex (vs. male sex) | 0.88 (0.58–1.34) | 0.55 | 0.74 (0.51–1.09) | 0.13 | 1.11 (0.76–1.61) | 0.60 | 1.08 (0.79–1.49) | 0.62 |

| Black, non-Hispanic/Latino race/ethnicity (vs. other race/ethnicities) | 0.88 (0.63–1.23) | 0.44 | 0.57 (0.40–0.81) | 0.002 | 0.69 (0.49–0.95) | 0.024 | 1.22 (0.93–1.59) | 0.15 |

| IDU HIV transmission risk (vs. other HIV transmission risks) | 0.32 (0.17–0.62) | < 0.001 | 1.24 (0.68–2.24) | 0.48 | 1.58 (0.93–2.69) | 0.09 | 2.18 (0.98–4.86) | 0.06 |

| Public/no insurance (vs. private insurance) | 0.66 (0.49–0.89) | 0.006 | 0.95 (0.69–1.29) | 0.72 | 0.88 (0.65–1.20) | 0.42 | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) | 0.25 |

| Viral load (per 1 log10 c/ml)** | 0.91 (0.75–1.12) | 0.37 | 0.88 (0.72–1.09) | 0.24 | 0.75 (0.61–0.91) | 0.005 | 0.73 (0.61–0.87) | < 0.001 |

| Baseline CD4+ cell count < 200 cells/mm3 (vs. ≥ 200 cells/mm3) | 0.79 (0.59–1.08) | 0.14 | 0.74 (0.53–1.03) | 0.07 | 0.89 (0.67–1.17) | 0.39 | 0.78 (0.58–1.04) | 0.09 |

| Twice or more daily dosing (vs. once daily dosing) | n/a | n/a | 0.71 (0.53–0.95) | 0.022 | 1.23 (0.83–1.82) | 0.30 | ||

| Boosted PI-containing cART (vs. NNRTI cART) | 0.95 (0.45–2.00) | 0.89 | 0.82 (0.55–1.21) | 0.32 | 1.09 (0.83–1.42) | 0.55 | 1.04 (0.77–1.42) | 0.79 |

| Unboosted PI-containing cART (vs. NNRTI cART) | 0.77 (0.58–1.02) | 0.06 | 0.84 (0.56–1.27) | 0.42 | 0.46 (0.24–0.87) | 0.017 | 1.38 (0.69–2.76) | 0.36 |

| Integrase or entry inhibitor-containing cART (vs. NNRTI cART) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1.17 (0.76–1.78) | 0.48 | |||

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; c/mL, copies per milliliter; CI, confidence interval; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; IDU, injection drug use; PI, protease inhibitor, NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; n/a, not applicable (variable not included in the model because not relevant in the specific calendar period of interest).

Undetectable viral load was defined as one below the limit of detection for each given viral load assay

Values were imputed for patients with missing pre-cART viral load (also see Table 2).

Discussion

In the HOPS, median durations of first and second cART regimens have increased significantly over time during the 15-year period represented in this analysis, corroborating reports from earlier cohorts that included regimens initiated up to 2009.5–7,15,16 These changes in cART regimen duration were temporally coincident with the availability of more tolerable, less complex cART regimens that required less frequent dosing. While median regimen durations were only approximately one year for both first and second cART among HOPS patients who initiated these regimens during the first two calendar periods of our study (1996–2003), they exceeded a median of two years in the latter two calendar periods (2004–2011), and approached 5 years for first cART in the most recent calendar period ending in 2011. For the earlier time periods, first cART regimen durations were similar to those recently reported for other U.S. cohorts4–6 but, with the 4.6 year median duration of first cART that we observed during the most recent calendar period (2008–2011), exceeded cART regimen durations recently reported from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study.7 As the duration of the first and second cART regimens increased over time, the percentage of persons who achieved viral suppression within 6 months of regimen initiation likewise increased markedly over time, corroborating randomized clinical trial-generated data that report improved potency, tolerability, and adherence associated with more contemporary regimens.17

Understanding cART regimen characteristics that were associated with increased rates of first cART modification and viral non-suppression in the most recent calendar period may inform regimen selection for contemporary patients. As in reports from other cohorts,5 we found that twice or more daily dosing was associated with increased rates of cART regimen modification and decreased rates of achieving viral suppression. Once-daily cART regimens are preferred in current HIV treatment guidelines for initial therapy.17 Furthermore, our findings concur with those from other cohorts suggesting that the use of NNRTI-containing regimens has been associated with decreased rates of cART modification compared with the use of some RTV-boosted PI-containing regimens.5,7,15,18

We found that black non-Hispanic race/ethnicity was a demographic associated with discontinuing or modifying cART for regimens initiated during 2008–2011. This could reflect lower regimen adherence among this patient group19–22 or other ART-related factors such as financial cost, tolerability, or toxicity. Notably, during this same time, black non-Hispanic race/ethnicity was not associated with diminished likelihood of achieving viral suppression.

There are important methodological issues relevant to the interpretation of our results. Earlier analysis from the HOPS cohort demonstrated that first cART regimens tend to be more durable than subsequent ones,2 which is consistent with clinical experience. However, no such trend emerged in our present multi-year study. We could not perform direct statistical comparisons of first and second cART regimen durations because many patients included the analyses of first cART were not included in the analyses of second cART and, by definition, observation on second cART follows observation on first cART, resulting in correlated data for some patients. Our analysis nonetheless indicates that effective and tolerable cART treatment options exist for treatment-experienced patients. In the most contemporary time period evaluated, the likelihood of achieving treatment success (i.e., remaining on durable, virally suppressive and tolerable cART) did not appear to differ substantially for cART-treated patients compared with patients newly initiating cART.

The findings from our study are subject to additional limitations and caveats. First, we analyzed data abstracted from medical records of patients in routine HIV care; specific reasons for regimen modification or discontinuation were not uniformly charted or were missing for many patients, and cART adherence data, which may have impacted regimen duration, were not systematically gathered. Second, because of patient aging and other demographic shifts occuring over time among HOPS participants initiating cART, it is possible that changes in cART regimen durations could be influenced by these shifts and were not due solely to improvements in cART potency, tolerability and regimen dosing during the timeframe of the study. Third, because we assessed percentages of patients who achieved viral suppression based on prevailing lower thresholds of detection for viral load, which were relatively higher in earlier calendar years, our findings related to temporal improvements in virologic suppression may be conservative. Fourth, despite the fact that the HOPS includes a large number of patients drawn from multiple and diverse HIV specialty clinics, our findings may not be generalizable to HIV-infected persons receiving cART in other care settings in the U.S. A recent analysis comparing characteristics of HOPS patients to all HIV-infected persons included in the national HIV Surveillance System revealed that HOPS patients tended to be older, and more frequently non-Hispanic white, non-injection drug using, and diagnosed with AIDS.23

In summary, among HOPS participants the duration of first and second cART regimens has increased substantially over time, particularly in the most recent (2008–2011) calendar period studied. Likewise, time to achievement of viral suppression after cART initiation decreased over time for both first and second cART recipients. Our findings likely reflect the benefits of newer cART regimens in terms of improved efficacy, tolerability, and simplicity (with once-daily dosing for many regimens). We identified a patient group for whom regimen modification was more likely during the most recent calendar period (i.e., persons of black non-Hispanic/Latino race/ethnicity), suggesting that interventions aimed at improving ART adherence and tolerability in this patient group are justified in order to extend cART regimen longevity. Trends in cART regimen use, regimen durability, and reasons for regimen modification warrant ongoing surveillance in order to better inform regimen selection for persons receiving initial and subsequent cART.

Acknowledgements

The HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) Investigators include the following persons and sites: John T. Brooks, Kate Buchacz, Marcus D. Durham, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV, Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA; Harlen Hays, Kathleen C. Wood, Darlene Hankerson, Rachel Hart, Thilakavathy Subramanian, Carl Armon, Bonnie Dean, and Sam Bozzette, Cerner Corporation, Vienna, VA; Frank J. Palella, Joan S. Chmiel, Carolyn Studney, Saira Jahangir, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL; Kenneth A. Lichtenstein and Cheryl Stewart, National Jewish Medical and Research Center Denver, CO; John Hammer, Kenneth S. Greenberg, Barbara Widick, and Rosa Franklin, Rose Medical Center, Denver, CO; Bienvenido G. Yangco and Kalliope Chagaris, Infectious Disease Research Institute, Tampa, FL; Doug Ward and Troy Thomas, Dupont Circle Physicians Group, Washington, DC; Jack Fuhrer, Linda Ording-Bauer, Rita Kelly, and Jane Esteves, State University of New York (SUNY), Stony Brook, NY; Ellen M. Tedaldi, Ramona A. Christian, Faye Ruley, Dania Beadle and Princess Graham, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA; Richard M. Novak, Andrea Wendrow and Renata Smith, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL; Benjamin Young, Barbara Widick, Mia Scott, APEX Family Medicine, Denver, CO. We also thank the HOPS participants and research staff.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: Financial support was received from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (contracts 200-2001-00133, 200-2006-18797, and 200-2011-41872) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (KL2TR000455 and UL1TR000454).

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: Presented in part as a poster at the XIX International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2012), Washington, DC, July 22–27, 2012 (poster number TUPE031).

Author contributions: A.N.S. wrote the manuscript and contributed to study design and data analysis. I.O., K.B., C.A., J.S.C., R.H., J.T.B., and F.J.P. contributed to study design, data analysis, and manuscript editing. R.B. contributed to data analysis and manuscript editing.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N.Engl.J Med. 1998;338(13):853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palella FJ, Jr, Chmiel JS, Moorman AC, Holmberg SD. Durability and predictors of success of highly active antiretroviral therapy for ambulatory HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2002;16(12):1617–1626. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200208160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips AN, Miller V, Sabin C, et al. Durability of HIV-1 viral suppression over 3.3 years with multi-drug antiretroviral therapy in previously drug-naive individuals. AIDS. 2001;15(18):2379–2384. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200112070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen RY, Westfall AO, Mugavero MJ, et al. Duration of highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens. Clin.Infect.Dis. 2003;37(5):714–722. doi: 10.1086/377271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willig JH, Abroms S, Westfall AO, et al. Increased regimen durability in the era of once-daily fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2008;22(15):1951–1960. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830efd79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juday T, Grimm K, Zoe-Powers A, Willig J, Kim E. A retrospective study of HIV antiretroviral treatment persistence in a commercially insured population in the United States. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1154–1162. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.543884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slama L, Li X, Brown T, et al. Increases in duration of first highly active antiretroviral therapy over time (1996–2009) and associated factors in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2014;65(1):57–64. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a99a0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gratacos L, Tuset M, Codina C, et al. [Antiretroviral therapy of HIV infection: duration and reasons for changing the first therapeutic regimen in 518 patients] Med.Clin.(Barc.) 2006;126(7):241–245. doi: 10.1157/13085280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mocroft A, Youle M, Moore A, et al. Reasons for modification and discontinuation of antiretrovirals: results from a single treatment centre. AIDS. 2001;15(2):185–194. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101260-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan Y, L'italien G, Mukherjee J, Iloeje UH. Determinants of discontinuation of initial highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens in a US HIV-infected patient cohort. HIV.Med. 2006;7(3):156–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackinnon A. The use and reporting of multiple imputation in medical research - a review. Journal of internal medicine. 2010;268(6):586–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Moorman AC, et al. Rates of hospitalizations and associated diagnoses in a large multisite cohort of HIV patients in the United States, 1994–2005. AIDS. 2008;22(11):1345–1354. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328304b38b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ, Jr, et al. Disparities in prevalence of key chronic diseases by gender and race/ethnicity among antiretroviral-treated HIV-infected adults in the US. Antiviral therapy. 2013;18(1):65–75. doi: 10.3851/IMP2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helleberg M, Kronborg G, Larsen CS, et al. Decreasing rate of multiple treatment modifications among individuals who initiated antiretroviral therapy in 1997–2009 in the Danish HIV Cohort Study. Antivir.Ther. 2012 doi: 10.3851/IMP2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abgrall S, Ingle SM, May MT, et al. Durability of first ART regimen and risk factors for modification, interruption or death in HIV-positive patients starting ART in Europe and North America 2002–2009. AIDS. 2013;27(5):803–813. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cb997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. [Accessed 10/20/2014];Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2014 http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf.

- 18.Cesar C, Shepherd BE, Krolewiecki AJ, et al. Rates and reasons for early change of first HAART in HIV-1-infected patients in 7 sites throughout the Caribbean and Latin America. PLoS.One. 2010;5(6):e10490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halkitis P, Palamar J, Mukherjee P. Analysis of HIV medication adherence in relation to person and treatment characteristics using hierarchical linear modeling. AIDS Patient.Care STDS. 2008;22(4):323–335. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyser M, Buchacz K, Bush TJ, et al. Factors associated with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the SUN study. AIDS Care. 2011;23(5):601–611. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh DL, Sarafian F, Silvestre A, et al. Evaluation of adherence and factors affecting adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among White, Hispanic, and Black men in the MACS Cohort. J Acquir.Immune.Defic.Syndr. 2009;52(2):290–293. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6d48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan PS, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV, Begley EB, Schulden J, Nakashima AK. Patient and regimen characteristics associated with self-reported nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy. PLoS.One. 2007;2(6):e552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchacz K, Hall I, Frazier E, Bryant D, Debes R, Huang P, Hu X, Brooks JT, Skarbinski J. A matter of perspective: comparison of the characteristics of HIV-infected persons in the United States from the HIV outpatient study, the medical monitoring project, and the National HIV Surveillance System. International AIDS Society Meeting; July 2015; Abstract WEPEC663. [Google Scholar]