Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gay and HIV-related stigma and discrimination are major barriers to accessing HIV prevention services among MSM worldwide. We aimed to identify modifiable factors that mediate the relationships between gay and HIV-related stigma and discrimination and HIV testing uptake among Chinese MSM.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional survey study of 523 HIV-uninfected or unknown MSM in Jiangsu Province, China between November 2013 and January 2014. Multivariable analyses were conducted to examine the associations among experienced homophobia, HIV stigma, and recent HIV testing. Causal mediation parametric analyses were conducted to assess whether depression and social norms mediated hypothesized associations.

RESULTS

Stronger subjective norms toward testing was associated with higher odds of recent HIV testing (AOR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.21) while increasing levels of depression and HIV stigma were both associated with lower odds of recent testing (AOR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.92, 0.99; and AOR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.84, 0.99, respectively). There was an indirect relationship (natural indirect effect) of experienced homophobia on recent testing (ORNIE: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.93, 0.98) mediated (35.0%) through depression. Furthermore, there was an indirect relationship of HIV stigma on recent testing (ORNIE: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.95, 0.99) mediated (19.2%) through subjective norms.

CONCLUSIONS

Depression and social norms are important mediators of HIV testing uptake among stigmatized Chinese MSM. Therefore, in addition to advocacy efforts and policies that address social-level stigma and discrimination, HIV prevention programs should also address mental health issues and incorporate community-based approaches to changing social norms toward HIV testing.

Keywords: HIV, homophobia, stigma, men who have sex with men, mediation, HIV testing

INTRODUCTION

Social stigma and discrimination, based on and directed at an individual’s behavioral characteristics or identity (e.g., same-sex behavior; gay or bisexual identity) and HIV-positive status, are major barriers to accessing HIV prevention and care services, including HIV testing and counseling, among men who have sex with men (MSM) worldwide.1–4 The HIV epidemic in China is now largely concentrated among MSM, who account for a third of new HIV infections.5 Many of these men do not access or cannot be reached by HIV prevention services. For instance, a meta-analysis reported that just 47% and 38% of Chinese MSM received HIV testing and counseling in their lifetime and in the past 12 months, respectively.6

Although same-sex behavior is not illegal in China, being MSM has significant negative social and cultural ramifications, which may include rejection by family and loss of employment.7 As a result, a majority of MSM do not disclose their same-sex behavior to others including health care providers. They also do not access HIV prevention services in fear that their sexual minority status would be exposed or they would encounter discrimination from health care workers.4,8 A global online survey reported that internalized homophobia was negatively associated with having ever tested for HIV among Chinese MSM.9 In addition to identity and/or behavior-related stigma, HIV-related stigma also discourages Chinese MSM from accessing HIV prevention and care services. While anti-HIV stigma campaigns have been implemented nationally, HIV stigma and discrimination are still highly prevalent among the general public as well as within MSM communities.10,11 A recent study found that higher levels of HIV-related stigmatizing and discriminatory attitudes were independently associated with lower uptake of recent HIV testing among MSM in Beijing.12 While it is important to document the effects of social stigma and discrimination on negative health outcomes, intervening at the level of stigma and discrimination may be the most difficult. Interventions usually require significant social actions, structural changes, and cultural shifts, all of which can be incremental. For example, a US study found that MSM living in more stigmatizing environments had decreased use of antiretroviral-based HIV prevention strategies compared to those in less stigmatizing environments, suggesting that legal reforms protecting sexual minorities might be necessary to reduce HIV risk among MSM.13 In the context of an expanding HIV epidemic among Chinese MSM, it is critical to identify modifiable factors that mediate the relationships between social stigma and discrimination and HIV risk and/or protective behaviors, upon which short- and medium-term interventions can be developed.

Increasing HIV testing uptake among MSM is a priority in the Chinese national HIV/AIDS strategic plan and there is a growing body of literature on this topic, however, few studies of Chinese MSM have assessed the effects of multiple psychosocial conditions on HIV testing or examined the impact of stigma on HIV testing through mediation models.9,14,15 A study of MSM in Hong Kong reported that subjective norms and perceived control were independently associated with lifetime and 12-month uptake of testing.15 In this paper, we examined the associations among experiences of homophobia, HIV stigma, and recent HIV testing among MSM in Jiangsu Province, China. In addition, we assessed whether depression and subjective norms toward HIV testing mediated hypothesized associations. Specifically, we examined whether: 1) Experiences of homophobia, HIV stigma, depression, and lack of subjective norms would each be negatively associated with recent HIV testing; 2) Depression would mediate the association between experiences of homophobia and recent HIV testing; and 3) Subjective norms would mediate the association between HIV stigma and recent HIV testing.

METHODS

Study Design and Recruitment

This is an analysis of baseline data of a longitudinal cohort study designed to evaluate the effects of an intervention in increasing HIV testing uptake among MSM in Jiangsu province, China. We conducted a cross-sectional survey study of MSM between November 2013 and January 2014. To be eligible to participate in the study, participants had to: 1) be biologically male; 2) age 18 or older; 3) be a resident in Jiangsu province; 4) have had oral or anal sex with another male in the past year; and 5) self-report being HIV uninfected or unknown. Furthermore, in order to track participants for follow-up surveys, we asked eligible participants to provide their contact information. As the intervention was implemented at MSM venues and on the Internet, we employed time-location sampling (TLS) and online convenience sampling to recruit a diverse sample of participants.

Time-location sampling (TLS) methodology has been described in detail elsewhere.16 It is used to sample MSM populations through creation of a sampling frame that comprises the universe of venues, days, and time periods where and when the population can be found to congregate. First, a formative phase constructed an up-to-date sampling frame of venues frequented by MSM and the days and time periods of attendance in Nanjing. From the roster of all possible venue-day-time (VDT) periods, a random sample of VDT was drawn. At the randomly selected VDT, the attendance of all potentially eligible subjects was counted and men entering or exiting the venue or crossing a predetermined line are intercepted, assessed for eligibility, and invited to participate.

During assessment, recruiters briefly described the study to men and asked if they were willing to participate. Men who had not previously participated were referred to an interviewer who administered the eligibility screener. Eligibility screening occurred in a private area of the venue or in a designated interviewing space near the venue. In addition to the above eligibility criteria, participants recruited through TLS also had to be consecutively approached by the staff at the randomly selected VDT (i.e., they could not approach staff on their own or at a later time). Once participants were determined eligible, staff reviewed informed consent with them using a tablet computer and addressed questions. To consent to the study, participants had to click the “Agree” button on the electronic informed consent. Staff then oriented participants to the tablet computer-assisted interview. Once participants were familiar with the operation of the tablet computer, they completed the self-administered survey and received an incentive for their participation. From November to December 2013, participants were recruited during 23 randomly selected venue-day-time periods. Staff enumerated 777 men from 10 venues, consecutively approached 478, screened 342 (71.5% eligibility determination), found 290 to be eligible (84.8% eligibility), and 261 (90.0% participation) consented to the study.

In addition to recruiting men from venues, we also posted our study advertisement on a popular provincial gay-oriented website to invite participation in our survey. By clicking on the advertisement, interested MSM were taken to the Internet-based survey webpage. The same eligibility screening and informed consent procedures were implemented for the online survey as the TLS. To prevent duplicate participation, a feature within the survey software program (www.qualtrics.com), which would not allow potential participants to access the survey more than once from the same IP address, was enabled. Furthermore, our staff double-checked the contact information provided by participants before giving out incentives for completing the survey. From mid November 2013 to mid January 2014, 985 potential participants clicked on our online survey advertisement or link. Of these, 941 entered the eligibility screening page and 823 answered all eligibility questions (87.5% eligibility determination), 592 met the eligibility criteria (71.9% eligibility), and 271 (45.8% participation) consented to the study.

The study was approved by the University of California – San Francisco’s Committee on Human Research and Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Socio-demographics

Participants were asked about their age, educational level, legal marital status, if they were cohabiting with a man or woman, official residential status (hukou), if they were living in the Nanjing Metropolitan Area (capital of the province), employment status, monthly gross income (1 USD ≈ 6 RMB), and sexual orientation.

Sexual behaviors

Participants reported on the number of male anal sex partners in the past six months, and whether or not condoms were used consistently with these male partners when engaging in insertive and / or receptive anal sex.

History of HIV testing

Participants were asked if they have ever been tested for HIV. Those who responded “Yes” were further asked about the number of HIV tests they had in the past year (“None,” “Once,” “Twice or more”). In the analysis, we dichotomized this outcome variable into having had versus having not had an HIV test in the past year. Participants who reported having never been tested were categorized as having not had an HIV test in the past year.

Experiences of homophobia

A 9-item scale was adapted to measure experiences of homophobia that happened to participants when they were growing up and during their adulthood because they were, or were thought to be, gay or bisexual (e.g., “Have you lost friends because of your sexual orientation?” “Have you been rejected by your family due to your sexual orientation?”).17 Response options were either “Yes” or “No.” Scores of the 9-item scale ranged from 0 to 9, with higher scores indicating greater experiences of homophobia (Cronbach’s α = 0.766).

Depression (CES-D 10)

A 10-item short form of the original CES-D scale was translated and adapted to screen for depressive symptomatology within the past week.18 Scores of CES-D 10 ranged from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s α = 0.811).

HIV stigma

The AIDS-related Stigma Scale was adapted to measure HIV stigma.19 The scale consists of 9 items that tap a broad range of stigmatizing beliefs including beliefs about negative qualities of people living with HIV/AIDS (e.g., dirty, cursed). In addition, based on our formative work with Chinese MSM, we added two items: “HIV-infected individuals must have been promiscuous,” and “I would distant myself from a friend who became infected with HIV.” Scores of this 11-item scale ranged from 0 to 11, with higher scores indicating more stigmatizing beliefs (Cronbach’s α = 0.805).

Subjective norm

A 4-item scale measured subjective norms toward HIV testing: “Most of your MSM friends think it is important to get tested for HIV;” “Most of your MSM friends get tested for HIV after having had unprotected sex;” “Most of your MSM friends get tested for HIV when they have new boyfriends or sex partners;” and “Most of your MSM friends think it is important to receive routine HIV testing.” Response options were measured using 4-point Likert scale, from “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree”. Scores ranged from 4 to 16, with higher scores indicating stronger norms toward testing (Cronbach’s α = 0.881).

Statistical Analysis

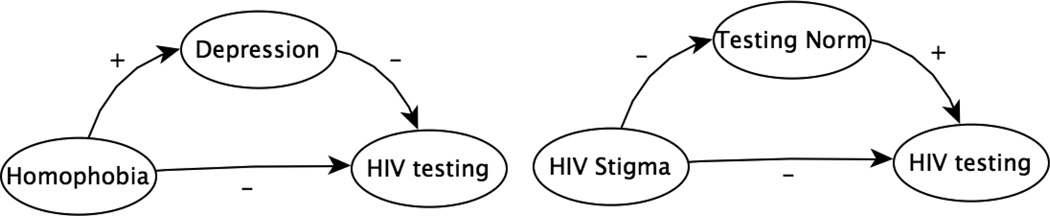

After cross-checking contact information provided by TLS and online participants, 7 duplicate records were excluded from analysis. In addition, 9 participants did not respond to questions regarding history of HIV testing, leaving a final sample size of 523 MSM participants. We conducted all analyses in STATA/SE 11 (College Station, Texas) with level of significance set at a 0.05 p-value. The univariate distribution of each variable on HIV testing behavior was assessed using chi-square tests for categorical variables or Mann-Whitney-U tests for continuous variables. To assess the conditional effects of variables on recent HIV testing, we fitted 3 separate multivariable logistic regression models, where inclusion of covariates was guided by Poundstone et al’s socio-epidemiological framework, literature review and causal diagrams (Figure 1).20–22 The first model assessed socio-demographic correlates of HIV testing behavior, variables with a p-value higher than 0.3 and did not have a priori research interest were excluded in subsequent models. Then a second model, restricted to those who reported ever having anal sex with a man, was fitted to assess the conditional effects of sexual behavioral risk factors associated with recent HIV testing. A third model was fitted to assess psychosocial factors associated with recent HIV testing. Prior to modeling, we multiply imputed the missing values (n=188, 35%) on subjective norm toward HIV testing, otherwise complete case analyses were used for all other variables and models.

Figure 1.

Causal mediation diagrams

To assess whether depression would mediate the association between experiences of homophobia and recent HIV testing, and whether subjective norms would mediate the relationship between HIV stigma and recent HIV testing, we conducted causal mediation parametric analysis with a counterfactual framework which is robust against more modeling misspecifications such as interaction and non-linearity.23 Using the STATA command (paramed) developed by Valeri and VanderWeele,23 we estimated the natural direct effect and the natural indirect effect by fitting a logistic regression for HIV testing conditional on experiences of homophobia and a set of covariates including age, marital status, employment status, hukou, place of residence and reported condomless receptive anal sex. We then fitted a linear regression model for depression conditional on experiences of homophobia and the same set of covariates.23 The same procedure was used for subjective norms and HIV stigma. However, since imputation procedures do not support the mediation analysis, we used complete case analysis and conducted sensitivity analyses on each imputed dataset to evaluate deviation of effect estimates across the complete-case and imputed datasets..

RESULTS

Of 523 participants, almost a third (156/523, 29.8%) had not been tested for HIV in the past year. Compared to participants who had been recently tested, those who had not been were significantly more likely to be married (17.2% vs. 28.2%, p = 0.001), and resided outside of Nanjing metropolitan area (32.7% vs. 43.6%, p = 0.018) (Table 1). Condomless receptive anal sex was more prevalent among those who reported no recent HIV testing compared to those who did (35.3% vs. 23.7%, p = 0.007). Stronger subjective norm toward testing was significantly and positively associated with recent testing (13.5 vs. 12.4, p = 0.005) while higher levels of HIV stigma and depressive symptoms were significantly and negatively associated with recent testing (2.5 vs. 1.9, p = 0.012; and 11.7 vs. 10.1, p = 0.012, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Frequencies of socio-demographic and sexual behavioral characteristics comparing MSM participants who have tested for HIV to those who have not in the past year, Jiangsu Province, China (N=523).

| HIV testing in the past year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No (N=156) | Yes (N=367) | |||||

| Explanatory variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | p |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–25 | 156 | 29.9 | 51 | 32.7 | 105 | 28.9 | 0.382 |

| 26–35 | 191 | 37.1 | 60 | 38.5 | 131 | 36.1 | |

| 36 or older | 172 | 33.0 | 45 | 28.9 | 127 | 35.0 | |

| Education | |||||||

| Middle school or less | 76 | 14.5 | 22 | 14.1 | 54 | 14.7 | 0.907 |

| High school or technical school | 227 | 43.4 | 70 | 44.9 | 157 | 42.8 | |

| College or higher | 220 | 42.1 | 64 | 41.0 | 156 | 42.5 | |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Single | 299 | 57.3 | 91 | 58.3 | 208 | 56.8 | 0.001 |

| Married | 107 | 20.5 | 44 | 28.2 | 63 | 17.2 | |

| Divorced/Separated | 116 | 22.2 | 21 | 13.5 | 95 | 26.0 | |

| Co-habitation | |||||||

| With a woman | 100 | 19.6 | 36 | 23.5 | 64 | 17.9 | 0.226 |

| With a man | 104 | 20.4 | 26 | 17.0 | 78 | 21.8 | |

| No | 307 | 60.1 | 91 | 59.5 | 216 | 60.3 | |

| Employment | |||||||

| Full time | 434 | 83.0 | 125 | 80.1 | 309 | 84.2 | 0.257 |

| Other | 89 | 17.0 | 31 | 19.8 | 58 | 15.8 | |

| Hukou | |||||||

| Nanjing/Jiangsu | 108 | 20.6 | 26 | 16.7 | 82 | 22.3 | 0.142 |

| Other province | 415 | 79.4 | 130 | 83.3 | 285 | 77.7 | |

| Location of residence | |||||||

| Nanjing metropolitan area | 335 | 64.1 | 88 | 56.4 | 247 | 67.3 | 0.018 |

| Outside of Nanjing | 188 | 35.9 | 68 | 43.6 | 120 | 32.7 | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | |||||||

| 2,999 or less | 177 | 33.8 | 57 | 36.5 | 120 | 32.7 | 0.695 |

| 3,000–4,999 | 198 | 37.9 | 57 | 36.5 | 141 | 38.4 | |

| 5,000 or higher | 148 | 28.3 | 42 | 26.9 | 106 | 28.9 | |

| Sexual orientation | |||||||

| Gay | 352 | 67.3 | 98 | 62.8 | 254 | 69.2 | 0.154 |

| Bisexual/Heterosexual/Not sure | 171 | 32.7 | 58 | 37.2 | 113 | 30.8 | |

| Number of male sex partners (past 6 months) | |||||||

| 0–1 | 195 | 39.2 | 58 | 38.9 | 137 | 39.4 | 0.493 |

| 2–5 | 226 | 45.5 | 64 | 43.0 | 162 | 46.6 | |

| 6 or above | 76 | 15.3 | 27 | 18.1 | 49 | 14.1 | |

| Condomless receptive anal sex (past 6 months) | |||||||

| Yes | 142 | 27.1 | 55 | 35.3 | 87 | 23.7 | 0.007 |

| No | 381 | 72.9 | 101 | 64.7 | 280 | 76.3 | |

| Condomless insertive anal sex (past 6 months) | |||||||

| Yes | 178 | 34.0 | 58 | 37.2 | 120 | 32.7 | 0.322 |

| No | 345 | 66.0 | 98 | 62.8 | 247 | 67.3 | |

Table 2.

Mean scores of psychosocial factors comparing MSM participants who have tested for HIV to those who have not in the past year, Jiangsu Province, China.

| HIV testing in the past year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| Cronbach’s α | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | pa | |

| Subjective norm (N=344) | .881 | 84 | 12.4 (3.1) | 260 | 13.5 (2.4) | 0.005 |

| HIV Stigma (N=517) | .805 | 153 | 2.5 (2.7) | 364 | 1.9 (2.3) | 0.012 |

| Experienced homophobia (N=514) | .766 | 151 | 4.5 (2.3) | 363 | 4.2 (2.6) | 0.227 |

| Depression (N=508) | .811 | 148 | 11.7 (5.8) | 360 | 10.1 (5.5) | 0.012 |

Note:

Mann-Whitney-U tests

Table 3 presents factors independently associated with recent HIV testing in three separate models. Model 1 included socio-demographic factors associated with recent testing. Compared to MSM who were between the ages of 18 and 25 and those who lived outside of Nanjing metropolitan area, MSM who were 36 or older and those who lived within Nanjing metropolitan area had higher odds of being recently tested (adjusted odds ratio (AOR): 2.00, 95% CI: 1.10, 3.67; and AOR: 1.71, 95% CI: 1.12, 2.61, respectively). After including sexual risk behaviors in Model 2, only those who reported condomless anal sex had lower odds of recent HIV testing compared to those who did not have any condomless anal sex (AOR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.93). Model 3 included psychosocial factors, where stronger subjective norm toward testing was associated with higher odds of recent HIV testing (AOR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.21) while increasing levels of depression and HIV stigma were both associated with lower odds of recent HIV testing (AOR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.92, 0.99; and AOR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.84, 0.99, respectively).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression models to determine socio-demographic, sexual behavioral and psychosocial factors independently associated with recent HIV testing among MSM participants in Jiangsu Province, China.

| Model 1 N=506 AOR (95% CI) |

p | Model 2 N=493* AOR (95% CI) |

p | Model 3a N=503 AOR (95% CI) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| 26–35 vs. 18–25 | 1.20 (0.72,1.99) | 0.480 | 1.17 (0.69, 1.97) | 0.532 | 1.17 (0.69, 1.97) | 0.557 |

| 36 or older vs. 18–25 | 2.00 (1.10, 3.67) | 0.025 | 1.70 (0.93, 3.12) | 0.086 | 1.67 (0.90, 3.10) | 0.105 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married vs. single | 0.66 (0.33, 1.33) | 0.247 | 0.49 (0.29, 0.86) | 0.015 | 0.62 (0.34, 1.12) | 0.116 |

| Divorced/Separated vs. single | 1.59 (0.88, 2.88) | 0.128 | 1.68 (0.92, 3.06) | 0.092 | 1.72 (0.96, 3.16) | 0.069 |

| Co-habitation | ||||||

| With a man vs. with a women | 1.37 (0.63, 2.98) | 0.425 | ||||

| No vs. with a women | 1.31 (0.67, 2.61) | 0.427 | ||||

| Employment | ||||||

| Other vs. Fulltime | 0.64 (0.37, 1.11) | 0.115 | 0.68 (0.38, 1.20) | 0.184 | 0.68 (0.38,1.18) | 0.171 |

| Hukou | ||||||

| Nanjing/Jiangsu vs. other | 1.66 (0.98, 2.79) | 0.058 | 1.48 (0.87, 2.52) | 0.148 | 1.51 (0.89, 2.58) | 0.129 |

| Location of residence | ||||||

| Nanjing Metro vs. outside | 1.71 (1.12, 2.61) | 0.013 | 1.60 (1.03, 2.48) | 0.036 | 1.44 (0.92, 3.16) | 0.069 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Gay vs. other | 0.80 (0.52, 1.24) | 0.315 | ||||

| Number of sex partners (past 6 months) | ||||||

| 2–5 vs. 0–1 | 1.35 (0.87, 2.13) | 0.187 | ||||

| 6 or above vs. 0–1 | 0.82 (0.45, 1.49) | 0.521 | ||||

| Condomless anal sex (past 6 months) | ||||||

| Receptive Yes vs. No | 0.56 (0.34, 0.93) | 0.030 | ||||

| Insertive Yes vs. No | 0.97 (0.60, 1.60) | 0.926 | ||||

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||

| Subjective norma | 1.10 (1.01 1.21) | 0.034 | ||||

| Depression | 0.96 (0.92, 0.99) | 0.041 | ||||

| HIV stigma | 0.91 (0.84, 0.99) | 0.036 | ||||

| Experienced homophobia | 1.03 (0.93, 1.12) | 0.385 |

Note:

Model 2 excluded those who had never had anal sex;

Parameter estimates were based on univariate imputation (10 copies) of missing values (N=188)

Table 4 presents estimated natural direct, indirect and total effects of the respective mediation pathways. Consistent with model 3 in Table 3, there was no evidence of a direct relationship (natural direct effect) between increasing level of experienced homophobia and recent HIV testing (OR natural direct effect (NDE): 0.96, 95% CI: 0.79, 1.00), however, there was evidence of an indirect relationship (natural indirect effect) of experienced homophobia on recent testing (OR natural indirect effect (NIE): 0.96, 95% CI: 0.93, 0.98) mediated (35.0%) through depression. In addition, there was evidence of a direct relationship between increasing level of HIV stigma and recent testing (ORNDE: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.83, 0.99) and an indirect relationship (ORNIE: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.95, 0.99) mediated (19.2%) through subjective norm toward testing. Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any notable differences in effect estimates across each imputed copies.

Table 4.

Estimates of direct and indirect effects of homophobia and HIV stigma on recent HIV testing behavior among MSM participants in Jiangsu Province, China with adjustment for age, employment, marital status, place of residence and condomless receptive anal sex.

| Natural direct effect | Natural indirect effect | Total effect | % Mediatedb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORNDE | 95% CIa | ORNIE | 95% CIa | ORTE | 95% CIa | ||

| Experienced homophobia -Depression | 0.96 | 0.79, 1.00 | 0.96* | 0.93, 0.98 | 0.89* | 0.73, 0.99 | 35.0% |

| HIV stigma- Subjective norm | 0.92* | 0.83, 0.99 | 0.98* | 0.95, 0.99 | 0.90* | 0.82, 0.98 | 19.2% |

Note:

significant at 0.05 critical value;

bootstrapped confidence interval with 1000 replications;

Calculated as log(ORnatural indirect effect)/log(ORtotal effect)

DISCUSSION

Consistent with findings from previous studies,4,12 our study found that HIV stigma was a significant barrier to HIV testing among Chinese MSM. While internalized homophobia has been found to deter Chinese MSM from seeking HIV testing,9 our results showed that experiences of homophobia was not significantly associated with recent HIV testing among MSM participants. This finding suggests that experiences of homophobia, which occurred during adolescence and early adulthood and were not directly related to encounters with health professionals, may be too distal to have an effect on recent health-seeking behaviors. However, the role of homophobia in negatively affecting sexual minorities’ HIV and non-HIV related health outcomes has been widely documented.24–26

Our study, more importantly, has demonstrated that not only did depression and community norms directly affect HIV testing uptake among Chinese MSM, they also mediated the effects of experienced homophobia and HIV stigma respectively on HIV testing behavior among this population. Depression has been consistently linked to HIV risks as well as HIV infection in the MSM literature.24,27,28 As the social environment for gays, bisexuals and other MSM in China is not likely to improve drastically in the near future, one can reasonably expect that mental health problems such as depression may play a key role in the HIV epidemic among Chinese MSM. Lessons learned from the West suggest that comprehensive HIV prevention for MSM should adopt a holistic approach to addressing these men’s overall health including mental health.29,30 However, at present, HIV programming for MSM in China is heavily focused on promoting condom use and HIV testing. But in order to improve these behavioral outcomes and ultimately reduce HIV infections, HIV prevention programs should strengthen their efforts in screening depressive symptoms among Chinese MSM and referring men with depression to appropriate mental health services.

In addition to individual-focused screening and treatment of depression, community-level interventions that are designed to change community norms toward HIV testing also need to be strengthened and scaled up. First, this will require continued and expanded support for community-based organizations to conduct outreach activities and peer-led education. Second, health communication campaigns that appeal to and resonate with the MSM communities should be implemented at larger scales. Existing and emerging models (e.g., social marketing and crowdsourcing) of health communication and marketing can guide the development of such campaigns.31,32 Finally, innovative strategies to harness the power of technologies should be developed and utilized to reach members of the virtual communities whom otherwise would not be reached through traditional outreach efforts.

This study has several limitations. First, our findings may not be generalizable to MSM who did not frequent MSM venues and those who did not visit the recruitment website. These men might be more “hidden” and less “out.” However, by using both TLS and online sampling, we believe our sample of participants was more diverse than a single sampling strategy could have achieved. Furthermore, the demographic and risk profiles of our online MSM sample were similar to those recruited through other methods such as respondent-driven sampling.33 Second, our data was cross-sectional and therefore causal inferences could not be made. In particular, depression was measured within the past week while HIV testing behavior measured within the past year. Hence, the depression measure was likely serving as a proxy for previous depression. However, results from the mediation analysis are similar to findings from a few longitudinal cohort studies.34,35 Third, participants’ responses were subject to recall and social desirability biases, although the mode of survey administration might have mitigated these biases.

In summary, our study showed that depression and community norms are important mediators of HIV testing uptake among stigmatized MSM in China. Therefore, HIV prevention programs should address mental health issues and incorporate community-based approaches to changing social norms toward HIV testing. Finally, MSM community-based advocacy efforts and government enforced policies that address overarching social-level stigma and discrimination against sexual minorities and MSM living with HIV should be supported and implemented.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was funded by a grant from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (grant number: R00MH093201).

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18640. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gari S, Doig-Acuna C, Smail T, et al. Access to HIV/AIDS care: a systematic review of socio-cultural determinants in low and high income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:198. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi KH, Lui H, Guo Y, et al. Lack of HIV testing and awareness of HIV infection among men who have sex with men, Beijing, China. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:33–43. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.China Ministry of Healht, UNAIDS, World Health Organization (WHO) 2009 estimates for the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China. Beijing, China: China Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou H, Hu N, Xin Q, et al. HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1717–1728. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0225-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Y, Wu Z, Detels R. Evolution of men who have sex with men community and experienced stigma among men who have sex with men in Chengdu, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(Suppl 1):S98–S103. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c7df71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei C, Yan H, Yang C, et al. Accessing HIV testing and treatment among men who have sex with men in China: a qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2014;26:372–378. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.824538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyun T, Santos GM, Arreola S, et al. Internalized homophobia and reduced HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2014;26:118–125. doi: 10.1177/1010539514524434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou YR. Homosexuality, seropositivity, and family obligations: perspectives of HIV-infected men who have sex with men in China. Cul Health Sex. 2006;8:487–500. doi: 10.1080/13691050600847455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He N, Detels R. The HIV epidemic in China: history, response, and challenge. Cell Res. 2005;15:825–832. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Lu H, Ma X, et al. HIV/AIDS-related stigmatizing and discriminatory attitudes and recent HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Beijing. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:499–507. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0161-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. State-level structural sexual stigma and HIV prevention in a national online sample of HIV-uninfected MSM in the United States. AIDS. 2015;29:837–845. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for AIDS/STDs Control and Prevention. Plan for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control among Men Who Have Sex with Men in China, 2007 – 2010. Beijing, China: Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu J, Lau JTF, Tsui H. Psychological factors in association with uptake of voluntary counseling and testing for HIV among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. Public Health. 2011;125:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacKellar D, Gallagher K, Finelayson T, et al. Surveillance of HIV risk and prevention behaviors of men who have sex with men-a national application of venue based, time-space sampling. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 1):S39–S47. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, et al. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: findings from 3 US cities. Am J Public Health. 91:927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, et al. Tow shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, et al. Development of a brief scale to measure AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-3895-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poundstone KE, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD. The social epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004;26:22–35. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glass TA, Goodman SN, Hernan MA, et al. Causal inference in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:61–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knuppel S. GAGitty: A graphical tool for analyzing casual diagrams. Epidemiology. 2011;22:745. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318225c2be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valeri L, VanderWeele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and casual interpretation: Theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods. 2013;18:137–150. doi: 10.1037/a0031034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrick AL, Lim SH, Plankey MW, et al. Adversity and syndemic production among men participating in the multicenter AIDS cohort study: a life-course approach. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:79–85. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatzenbuehler ML, Bellatorre A, Lee Y, et al. Structural stigma and all-cause mortality in sexual minority populations. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duncan DT, Hatzenbuehler ML. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender hate crimes and suicidality among a population-based sample of sexual-minority adolescents in Boston. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:272–278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos GM, Do T, Beck J, et al. Syndemic conditions associated with increased HIV risk in a global sample of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:250–253. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guadamuz TE, McCarthy K, Wimonsate W, et al. Psychosocial health conditions and HIV prevalence and incidence in a cohort of men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand: evidence of a syndemic effect. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:2089–2096. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0826-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safren SA, Reisner SL, Herrick A, et al. Mental health and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S74–S77. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbc939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayer KH, Bekker LG, Stall R, et al. Comprehensive clinical care for men who have sex with men: an integrated approach. Lancet. 2012;380:378–387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60835-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andreasen A. Marketing social change: Changing behavior to promote health, social development, and the environment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howe J. The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired Magazine. 2006;14:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang W, Huan X, Mahapatra T, et al. Factors associated with unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men: results from a respondent-driven sampling survey in Nanjing, China, 2008. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1415–1422. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mimiaga MJ, O’Cleirigh C, Biello KB, et al. The effect of psychosocial syndemic production on 4-year HIV incidence and risk behavior in a large cohort of sexually active men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:329–336. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halkitis PN, Kapadia F, Bub KL, et al. A longitudinal investigation of syndemic conditions among young gay, bisexual, and other MSM: The P18 cohort study. AIDS Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0892-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]