Abstract

Background

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is the most expensive birth defect managed in the United States, with a 5-year survival rate below 70%. Increasing evidence suggests that hospital volumes are inversely associated with mortality for infants with single ventricles undergoing stage 1 surgical palliation. Our aim was to examine the relative effects of surgeon and institutional volumes on outcomes and resource utilization for these children.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted using the Pediatric Health Information System database to examine the effects of the number of procedures performed per surgeon and per center on mortality, costs, and postoperative length of stay for infants undergoing RACHS-1 risk category six operations at tertiary pediatric hospitals, 1/1/2004–12/31/13. Multivariable modeling was used, adjusting for patient and institutional characteristics. Gaussian kernel densities were constructed to show the relative distributions of the effects of individual institutions and surgeons, before and after adjusting for the number of cases performed.

Results

2,880 infants from 35 institutions met inclusion criteria. Mortality was 15.0%. Median postoperative length of stay was 24 days (IQR 14–41). Median standardized inpatient hospital costs were $156,000 (IQR $108,000–$248,000) in 2013 dollars. In multivariable analyses, higher institutional volume was inversely associated with mortality (p=0.001), postoperative length of stay (p=0.004), and costs (p=0.001). Surgeon volume was associated with none of the measured outcomes. Neither institutional nor surgeon volume explained much of the wide variation in outcomes and resource utilization observed between institutions and between surgeons.

Conclusions

Increased institutional—but not surgeon—volumes are associated with reduced mortality, postoperative length of stay, and costs for infants undergoing stage 1 palliation.

Keywords: Hypoplastic left heart syndrome, Norwood, institutional volume, surgeon volume, outcomes, costs

Introduction

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is the most expensive birth defect managed in the United States; during the first hospitalization, an average child with hypoplastic left heart syndrome accumulates approximately $200,000 in direct medical charges,1 a figure which has risen by more than 50 percent in the last 10 years.2 Despite rapidly rising costs, our understanding of what drives costs for these children, and the association between changes in costs and changes in outcomes, remains limited.

Previous studies have generally described an inverse relationship between center volume and mortality for children undergoing congenital heart surgery3–8, and, in particular, for those undergoing higher risk procedures, such as stage-one single ventricle palliation.8–10 Limited data exist regarding the relative effects of institution and surgeon volumes on clinical outcomes for these children.11–15 To the best of our knowledge, no data exist regarding the effects of surgeon volumes on costs. This study was undertaken to elucidate the relative effects of surgeon and institutional volumes on resource utilization for infants with single ventricles undergoing stage 1 surgical palliation—Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS-1) score six—at tertiary pediatric hospitals in the United States.

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective study to determine the relative effects of surgeon and institutional volumes on hospital mortality, post-operative length of stay, and inpatient standardized direct medical costs for infants undergoing stage1palliation. This study was classified as non-human subjects research by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board, under 45 CFR 46.102(f), and was exempted from further review.

Data source

Data for this study were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, an administrative database that contains inpatient, emergency department, ambulatory surgery and observation data from 44 not-for-profit, tertiary care pediatric hospitals in the United States. These hospitals are affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Overland Park, KS). Data quality and reliability are assured through a joint effort between the Children’s Hospital Association and participating hospitals. The data warehouse function for the PHIS database is managed by Truven Health Analytics (Ann Arbor, MI). For the purposes of external benchmarking, participating hospitals provide discharge/encounter data including demographics, diagnoses, and procedures. Forty of these hospitals submit billing data, including cost-to-charge ratios, to the database, allowing for the estimation of costs. All data are de-identified at the time of data submission, and data are subjected to a number of reliability and validity checks before being included in the database.

Study Population

The database was queried for all infants discharged between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2013 undergoing stage 1 single ventricle palliation. Subjects were considered to have undergone stage 1 palliation based on a Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS-1) score of six (Stage 1 repair of hypoplastic left heart syndrome—Norwood operation, Stage 1 repair of nonhypoplastic left heart syndrome conditions, and the Damus-Kaye-Stansel procedure).16 Patients were excluded if the procedure was performed after 90 days of age (n=9 patients). Centers performing fewer than ten RACHS-1 risk category six procedures during the entire nine-year study period (n=1 centers) and those with >15% missing data for any pre-operative variable (n=4 centers) were excluded. Three centers submit clinical, but not charge data; these centers were excluded from cost analyses.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were: 1) Hospital mortality (not limited to 30 days), 2) postoperative length of stay, and 3) total inpatient standardized costs. Postoperative length of stay was defined as the total length of hospital stay after stage 1 palliation, not limited to the intensive care unit. Date of surgery was missing for two subjects (0.7%); these subjects were eliminated from analyses of postoperative length of stay. We sought to use hospitalization costs as a surrogate for the volume of resources expended. Therefore, we used standardized costs, available through the PHIS database, to account for the high inter-hospital variability in item costs.17 In brief, line-item charges and the number of billed units were tabulated for every resource in the PHIS database (classified using Truven Health Analytics’ Clinical Transaction Classification (CTC) system). The median costs were then computed per CTC code, using hospital- and department-specific cost-to-charge ratios. The charges listed in the database already adjust for costs of living by hospital location, using the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Wage Index (http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Wage-Index-Files.html). The median cost for each CTC code for each hospital was then calculated, and the medians of hospital median unit costs were used to define standardized costs. These standardized costs were used to calculate total hospitalization costs for each admission.17 Costs were adjusted for inflation (to US 2013 dollars), using the Medical Consumer Price Index (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/#tables). In exploratory analyses, costs per day were also considered, calculated by dividing total inpatient hospital costs by the total length of hospital stay.

Predictors of Interest

The primary predictors of interest were surgeon and institutional volumes. Surgeon volumes were defined as the total number of operations in the database performed by a provider or at an institution each year. This was used as a proxy for total case volume. The average numbers of operation performed over the entire study period (per surgeon and per institution) were also tested, with similar results. Coding methodology for surgeons in the database changed partway through our study period. Under both sets of coding, unique identifiers were used, but only using the second set of coding could these identifiers be linked to National Provider Index (NPI) numbers, allowing us to track surgeon movement across institutions within the database. Insufficient data existed to link the surgeon codes for 16.5% of subjects to an NPI number. Subjects for whom there was either no coded surgeon, or for whom the billing physician performed fewer than three operations over two or fewer years and who could not be reliably linked to the NPI number of a cardiothoracic surgeon operating at a given institution during the study period, were considered to have missing surgeon data and the subjects were excluded from multivariable analyses (n=56, 1.9%, distributed evenly across 22 hospitals). Although the subjects were excluded, their contribution to the institutional volumes was retained. For the estimates of the number of cases performed per surgeon, a portion of the number of operations each year for whom surgeon was not defined was added to the number of operations known to have been performed by each surgeon each year. This portion was assigned proportionate to the known number of operations performed by each surgeon, at each institution. In multivariable models including both institutional volume and surgeon volume, institutional volume was defined as the total, annual institutional volume less the annual volume of the operating surgeon, to account for collinearity between surgeon and institutional volumes. All but two institutions contributed data for the entire study period; these institutions contributed six and eight years respectively.

Data was also collected on sex, birth weight, prematurity, the presence of major non-cardiac comorbid conditions (as previously defined by Feudtner et al.18), hypoplastic left heart syndrome, year of admission (to reflect surgical era), age on admission, prolonged preoperative length of stay (>75%ile), insurance type (Medicaid versus non-Medicaid), and institution.

Missing data were rare. Data were only missing for sex (n=1, <0.1%), insurance type (n=5, 0.2%), and birth weight (n=102, 3.5%). Subjects for whom data were missing were excluded from multivariable analyses. Neither the risk of mortality, nor postoperative length of stay, nor costs, differed significantly between subjects with known versus missing sex, insurance type, or birth weight.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata software, version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Clinical and demographic variables were described with standard summary statistics, using means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. After carefully considering different transformations and assessing the relationships between surgeon and institution volumes and the outcomes of interest via nonparametric regression techniques, it was determined that, for all three outcomes of interest, both institutional and surgeon volumes were best modeled as continuous, linear, variables. For descriptive purposes, volumes were also considered as categorical variables, divided into low, medium, and high by tertile. Institutional volume tertiles were defined as ≤10, 10–19, and >19 cases per year; Surgeon volume tertiles were defined as ≤5, 5–8.7, and >8.7 cases per year.

To assess the magnitude of the associations between the primary predictors of interest and the measured outcomes, univariable and multivariable regression techniques were used. Logistic regression was used to estimate the relationships between the primary predictors of interest and mortality. Linear regression was used to estimate the relationships between the primary predictors of interest and the log of postoperative length of stay and the log of standardized total inpatient hospital costs. Institutional and surgeon volumes were first entered into the models in isolation, to assess their unadjusted effects on the measured outcomes. Covariates for patient characteristics considered in previous studies to be significantly associated with clinical outcomes (sex, birth weight, prematurity, major comorbid condition, dominant right ventricle, year of admission, long preoperative time, and insurance type) were then added to these models. Lastly, institutional and surgeon volumes were entered into the models jointly, along with the aforementioned patient characteristics. Model-based confidence intervals were constructed and hypothesis tests were performed using robust standard errors, with clusters corresponding to institutions.19 A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Because some children undergoing stage 1 palliation die prior to discharge, and because neither postoperative days nor costs accrue post mortem, standard linear regression can incompletely capture sources of variation in these two measures of resource utilization. Therefore, Tobit (censored regression) models were also fit.20 Tobit models retain information about all subjects, while simultaneously accounting for the fact that the outcomes of interest are artificially truncated in subjects who die.

Uncensored models that included multi-level clustering (institution and surgeon) were also tested. Multi-level clustering had minimal effect on our standard errors. To allow for the inclusion of censoring, therefore, clustering was included only on the highest level—institution.21, 22

To test the possibility that a small number of outliers might be driving our results, models were also tested excluding first patients with costs or lengths of stay greater than the 95 percentile and then excluding surgeons and institutions with mortality rates, costs, or lengths of stay greater than the 95th percentile. Given that some patients are transferred postoperatively to other institutions and that these data do not account for mortality, costs, or hospital days accumulated post transfer, models were also tested excluding transferred patients. We also tested for interaction and effect modification.

To better understand the degree to which hospital volumes explain variation in outcomes and resource utilization between institutions, linear probability models were fit for mortality and censored linear regression models were fit for the log of postoperative length of stay and log of standardized total inpatient hospital costs, in which we included institutions as fixed effects, as well as important clinical characteristics (as above). These models were fit with and without institutional and surgeon volumes as covariates. Gaussian kernel densities were constructed to show the relative distributions of the regression coefficients for the fixed institutional and surgeon effects from these models with and institutional and surgeon volumes. A kernel density plot is essentially a smoothed version of a histogram. Such plots are sometimes preferred over their histogram counterparts because their construction does not depend upon a user-specified number of bins or upon the end points of those bins. Kernel density plots do require the selection of a bandwidth parameter, but can allow for easier visualization of important features of the distribution of a variable. In our plots, we take the magnitude of the fixed effects (regression coefficients) of either the centers or surgeons from each of our multivariable models as the as the variables of interest.

Results

Patient, Surgeon, and Institutional Characteristics

A total of 2,880 infants at 35 institutions underwent stage 1 palliation, during the nine-year study period. Cost data was available for 2,724 subjects from 32 institutions. The median surgeon had an annual stage 1 palliation case volume of three procedures per year (IQR 2–6, range 1–32) and the median institution had an annual case volume of eight procedures per year (IQR 4–14, range 1–45). The total number of procedures performed per year for the entire cohort was relatively constant across the nine-year study period. Sex, birth weight, and prematurity were similar across both institutional and surgeon volumes. Patients operated on at higher volume institutions were less likely to have major non-cardiac comorbid conditions than those operated on at lower volume institutions (p = 0.024). The prevalence of a major non-cardiac comorbid condition did not differ by surgeon volume (p = 0.946), though patients operated on by higher volume surgeons were more likely to have hypoplastic left ventricles (p < 0.001). The median age on admission was zero for all surgeon and institutional volume tertiles, but children at lower volume hospitals and children operated on by lower volume surgeons were more likely to have prolonged preoperative lengths of stay (p < 0.001 and p = 0.010, respectively). Median age at operation was 6 days (IQR 4–9, 95%ile 21 days). The proportion of patients on Medicaid insurance was also inversely associated with institutional volume (p = 0.011), with a greater proportion of patients at low volume centers covered by Medicaid than at medium or high volume centers (p = 0.001 and < 0.001, respectively). There was no difference in Medicaid coverage by surgeon volume. More detailed patient characteristics are described in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics overall and by institution and surgeon volumes (n = 2,889)

| Institution | Surgeon | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Low Volume (≤10 cases/yr) |

Medium Volume (10–19 cases/yr) |

High Volume (>19 cases/yr) |

p value | Low Volume (<5 cases/yr) |

Medium Volume (5–8.7 cases/yr) |

High Volume (>8.7 cases/yr) |

p value | |

| Male sex | 1,754 (60.9%) | 567 (59.6%) | 607 (62.6%) | 580 (60.5%) | 0.574 | 716 (61.5%) | 441 (61.4%) | 597 (59.9%) | 0.861 |

| Birth weight in kg | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.5) | 0.623 | 3.1 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.5) | 0.618 |

| Prematurity | 350 (12.1%) | 122 (12.8%) | 125 (12.9%) | 103 (10.7%) | 0.116 | 138 (11.9%) | 105 (14.6%) | 107 (10.7%) | 0.119 |

| Major comorbid condition | 657 (22.8%) | 237 (24.9%) | 214 (22.1%) | 206 (21.5%) | 0.024* | 265 (22.8%) | 153 (21.3%) | 239 (24.0%) | 0.946 |

| Hypoplastic left heart | 2,091 (72.6%) | 663 (69.7%) | 725 (74.7%) | 703 (73.3%) | 0.053 | 794 (68.2%) | 546 (76.0%) | 751 (75.3%) | <0.001* |

| Admit age (days) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | <0.001* | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 0.001* |

| Long preoperative time§ | 654 (22.7%) | 265 (27.9%) | 219 (22.6%) | 170 (17.7%) | <0.001* | 278 (23.9%) | 172 (24.0%) | 204 (20.5%) | 0.010* |

| Medicaid insurance | 1,361 (47.3%) | 476 (50.3%) | 454 (46.9%) | 431 (44.9%) | 0.011* | 554 (47.7%) | 334 (46.6%) | 473 (47.4%) | 0.584 |

| Institutional volume by year | 14 (9–21) | --- | --- | --- | --- | 9 (5–14) | 13 (10–17) | 21 (17–28) | <0.001* |

| Surgeon volume by year | 7 (4–11) | 4 (2–6) | 7 (5–9) | 12 (7–15) | <0.001* | --- | --- | --- | --- |

Values are n (%), mean ± SD, or median (IQR). Volumes are divided by tertile into low, medium, and high. p values reflect associations with volumes, when volumes are considered as continuous variables.

Denotes p < 0.05.

Long preoperative time is defined as >75%ile (> 9 days).

Table 2.

Unadjusted mortality, lengths of stay, and costs, by institution and surgeon volume tertiles.

| Institution | Surgeon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Volume (<10 cases/yr) |

Medium Volume (10–19 cases/yr) |

High Volume (>19 cases/yr) |

p value | Low Volume (<5 cases/yr) |

Medium Volume (5–8.7 cases/yr) |

High Volume (>8.7 cases/yr) |

p value | |

| Mortality | 15.7% | 17.0% | 12.3% | 0.001* | 14.9% | 14.4% | 15.7% | |

| 0.624 | ||||||||

| LOS | 32 (21–54) |

30 (20–47) |

27 (17–45) |

<0.001* | 29 (20–49) |

33 (22–52) |

28 (17–47) |

0.267 |

| LOS for Survivors | 32 (22–52) |

31 (22–46) |

27 (17–43) |

<0.001* | 29 (21–48) |

33 (23–51) |

29 (18–47) |

0.248 |

| Postoperative LOS | 25 (15–46) |

24 (15–40) |

22 (13–39) |

0.005* | 23 (14–40) |

26 (16–44) |

23 (13–41) |

0.423 |

| Postoperative LOS for Survivors | 25 (16–45) |

25 (16–40) |

22 (14–37) |

0.003* | 23 (15–40) |

26 (16–42) |

24 (14–40) |

0.493 |

| Costs | $175K ($119K – $288K) |

$153K ($112K – $244K) |

$137K ($93K – $218K) |

0.003* | $158K ($108K – $254K) |

$164K ($112K – $258K) |

$152K ($100K – $237K) |

0.327 |

| Costs for Survivors | $166K ($116K – $263K) |

$153K ($112K – $224K) |

$134K ($91K – $198K) |

0.005* | $150K ($107K – $233K) |

$155K ($111K – $242K) |

$146K ($96K – $220K) |

0.228 |

| Costs / day | $5,300 ($4,300 – $6,500) |

$5,100 ($4,300 – $6,500) |

$5,000 ($4,200 – $6,300) |

0.410 | $5,200 ($4,200 – $6,600) |

$5,100 ($4,200 – $6,200) |

$5,100 ($4,300 – $6,400) |

0.739 |

| Costs / day for Survivors | $5,000 ($4,200 – $6,000) |

$4,900 ($4,200 – $5,800) |

$4,800 ($4,100 – $5,800) |

0.439 | $5,000 ($4,200 – $6,000) |

$4,900 ($4,100 – $5,800) |

$4,800 ($4,200 – $5,800) |

0.947 |

Values are percentages or medians (IQRs). Volumes are divided by tertile into low, medium, and high. All costs are reported in 2013 dollars.

LOS = length of stay.

p values reflect associations with volumes, when volumes are considered as continuous variables, clustering standard errors on institution.

Denotes p < 0.05.

Mortality

Overall mortality was 15.0% (n=432). In unadjusted analyses, for every 10 additional stage 1 palliation procedure performed per institution per year, the odds of mortality decreased by 16% (95% CI 6–24%; p = 0.001). A similar effect was observed after adjusting for patient characteristics (18% decrease, 95% CI 10–26%; p < 0.001). Surgeon volumes were not themselves significantly associated with the odds of mortality in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses. These results were insensitive to the presence of outliers or transferred patients. There was an interaction between the effects of surgeon and center volumes, with slightly greater center volume effects observed among higher volume surgeons.

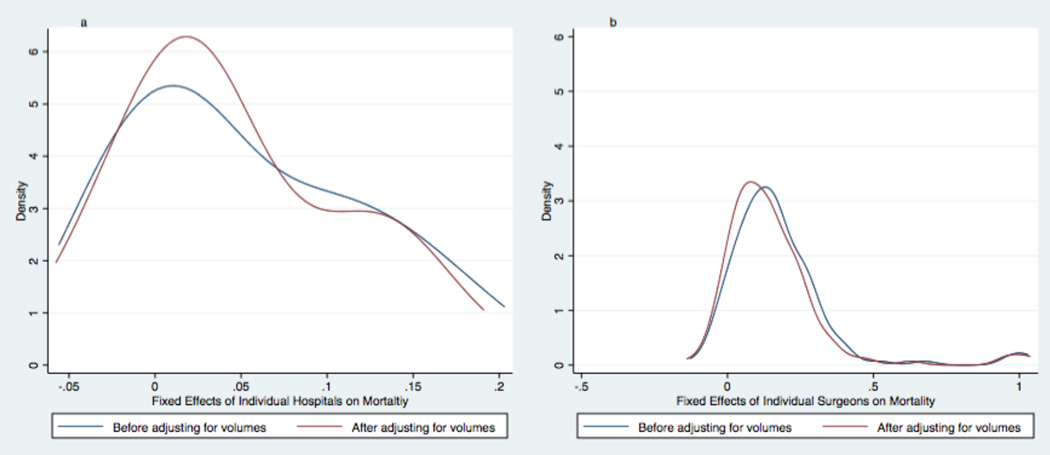

There was marked variation in mortality observed between institutions and between surgeons. Mortality rates per institution ranged from 7.2% to 29.6% (5th and 95th percentiles). Mortality rates per surgeon ranged from 0.0% to 40.0% (5th and 95th percentiles). This variation was similar before and after adjusting for either institutional or surgeon volumes. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Effects of Volumes on the Variation in Mortality between Institutions and between Surgeons.

Kernel density plots graphically display differences in the distribution of hospital (Fig. 1a) and surgeon (Fig. 1b) fixed effects on mortality for infants undergoing stage 1 palliation. Blue lines show the distribution of fixed effects before adjusting multivariable models for institutional or surgeon volumes. Red lines show the distribution of fixed effects before adjusting multivariable models for institutional or surgeon volumes. Neither the variation between institutions nor the variation between surgeons changed substantially after adjusting for volumes.

Postoperative length of stay

The median overall length of stay was 30 days (IQR 19–50), with a median overall postoperative length of stay of 24 days (IQR 14–41). Both total length of stay and postoperative length of stay were significantly longer for survivors (medians 30 and 24 days, respectively) than for those patients who died prior to discharge (medians 27 and 18 days, respectively; p = 0.002 and p < 0.001). Surgeon volume was not associated with postoperative length of stay in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses.

In unadjusted analyses, for every 10 additional stage 1 palliation procedures performed per institution per year postoperative length of stay decreased by 8% (95% CI 3–13%; p = 0.005). The magnitude of the association between institutional volume and postoperative length of stay was similar after adjusting for patient characteristics and surgeon volumes and after censoring for death. In adjusted analyses, for every 10 additional stage 1 palliation procedures performed per institution per year postoperative length of stay decreased by 11% (95% CI 4–18%; p = 0.004). These results were insensitive to the presence of outliers or transferred patients. There was no significant interaction between the effects of center and surgeon volumes on postoperative length of stay.

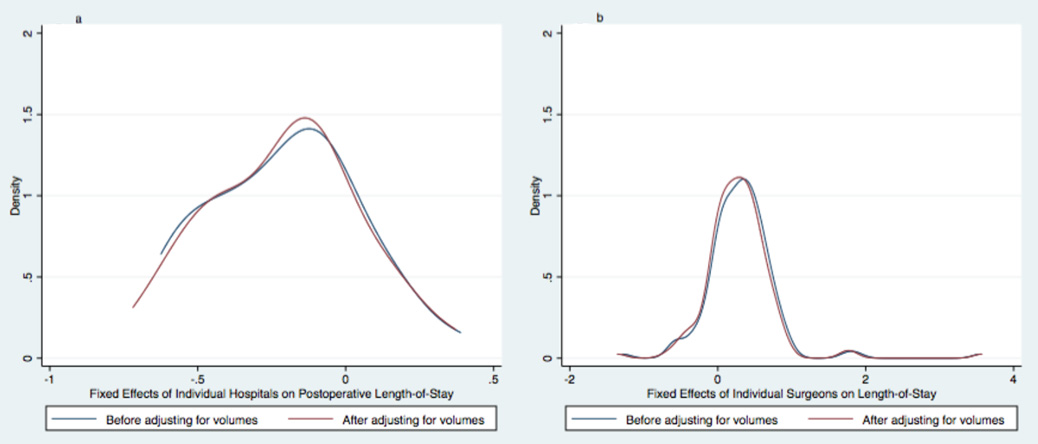

There was marked variation in postoperative length of stay observed between institutions and between surgeons. Median postoperative length of stay per institution ranged from 16 to 39 days (5th and 95th percentiles). Median postoperative length of stay per surgeon ranged from 12 and 49 days (5th and 95th percentiles). This variation was similar before and after adjusting for either institutional or surgeon volumes. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Effects of Volumes on the Variation in Postoperative Length of stay between Institutions and between Surgeons.

Kernel density plots graphically display differences in the distribution of hospital (Fig. 2a) and surgeon (Fig. 2b) fixed effects on postoperative length of stay for infants undergoing stage 1 palliation. Blue lines show the distribution of fixed effects before adjusting multivariable models for institutional or surgeon volumes. Red lines show the distribution of fixed effects before adjusting multivariable models for institutional or surgeon volumes. Neither the variation between institutions nor the variation between surgeons changed substantially after adjusting for volumes.

Costs

Median total, adjusted standardized costs per patient were $156,000 (IQR $108,000–$248,000), in 2013 dollars. In unadjusted analyses, for every 10 additional stage 1 palliation procedures performed per institution per year total hospital costs decreased by 13% (5–21%; p = 0.003). The magnitude of this association was similar after adjusting for patient characteristics. The point estimates for the magnitude of the association was slightly more pronounced after adjusting for surgeon volume (16%, 95% CI 6–25%; p = 0.004) and censoring for death (19%, 95% CI 8–28%; p = 0.001). Surgeon volume was not significantly associated with hospital costs in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses. See Table 3. These results were insensitive to the presence of outliers or transferred patients. There was no significant interaction between the effects of center and surgeon volumes on costs.

Table 3.

The relative effects of surgeon and institutional volumes on mortality, postoperative length of stay, and costs.

| Institution Volume§, Unadjusted |

Institution Volume§, Adjusted for Patient Characteristics |

Institution Volume§, Adjusted for Patient Characteristics & Surgeon Volume |

Surgeon Volume‡, Unadjusted |

Surgeon Volume‡ Adjusted for Patient Characteristics |

Surgeon Volume‡ Adjusted for Patient Characteristics & Institution Volume |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR or eβ (95% CI) p value |

OR or eβ (95% CI) p value |

|||||

| Mortality | 0.84 (0.76–0.94) 0.001* |

0.82 (0.74–0.90) <0.001* |

0.70 (0.56–0.89) 0.001* |

1.05 (0.87–1.25) 0.624 |

1.02 (0.84–1.24) 0.877 |

1.02 (0.87–1.20) 0.819 |

| Postoperative Length of stay† | ||||||

| Uncensored | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) 0.005* |

0.95 (0.90–1.00) 0.055 |

0.93 (0.86–1.00) 0.060 |

0.98 (0.92–1.03) 0423 |

0.99 (0.95–1.03) 0.608 |

0.99 (0.95–1.03) 0.544 |

| Censored | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) 0.001* |

0.92 (0.86–0.98) 0.006* |

0.89 (0.82–0.96) 0.004* |

0.99 (0.91–1.06) 0.699 |

0.99 (0.92–1.06) 0.737 |

0.99 (0.93–1.05) 0.698 |

| Standardized Costs† | ||||||

| Uncensored | 0.87 (0.79–0.95) 0.032* |

0.87 (0.78–0.96) 0.010* |

0.84 (0.75–0.94) 0.004* |

0.97 (0.92–1.02) 0.221 |

0.96 (0.90–1.03) 0.243 |

0.97 (0.92–1.02) 0.221 |

| Censored | 0.85 (0.78–0.94) 0.001* |

0.85 (0.76–0.95) 0.003* |

0.81 (0.72–0.92) 0.001* |

0.97 (0.91–1.03) 0.257 |

0.96 (0.89–1.04) 0.283 |

0.97 (0.91–1.03) 0.257 |

| Costs per day | ||||||

| Uncensored |

0.96 (0.88–1.05) 0.410 |

0.94 (0.85–1.03) 0.201 |

0.92 (0.82–1.03) 0.136 |

1.01 (0.96–1.06) 0.739 |

0.99 (0.94–1.04) 0.698 |

0.99 (0.95–1.04) 0.784 |

| Censored |

0.95 (0.87–1.05) 0.321 |

0.93 (0.84–1.03) 0.157 |

0.91 (0.81–1.02) 0.099 |

1.01 (0.96–1.06) 0.700 |

0.99 (0.94–1.04) 0.700 |

0.99 (0.95–1.04) 0.790 |

Models for mortality were constructed using logistic regression, clustering standard errors on institution; odds ratios (OR) are presented.

Models for length of stay and costs were constructed using linear or censored linear regression, clustering standard errors on institution. Models were built using the natural log of length of stay and standardized costs, adjusted to 2013 dollars; for ease of interpretation, back-transformed coefficients (eβ) are presented.

Institution volume was considered as a continuous variable, with units of 10 operations per year.

Surgeon volume was considered as a continuous variable, with units of 5 operations per year.

Denotes p < 0.05

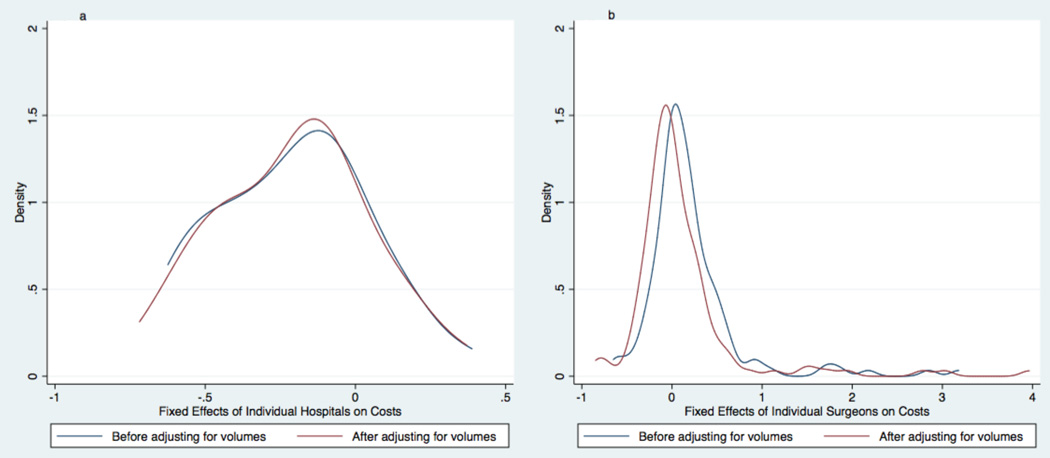

There was marked variation in total hospital costs observed between institutions and between surgeons. Median hospital costs per institution ranged from $111,000 to $292,000 (5th and 95th percentiles). Median hospital costs per surgeon ranged from $97,000 and $416,000 (5th and 95th percentiles). This variation also was similar before and after adjusting for either institutional or surgeon volumes. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. The Effects of Volumes on the Variation in Total Inpatient Hospital Costs between Institutions and between Surgeons.

Kernel density plots graphically display differences in the distribution of hospital (Fig. 3a) and surgeon (Fig. 3b) fixed effects on costs for infants undergoing stage 1 palliation. Blue lines show the distribution of fixed effects before adjusting multivariable models for institutional or surgeon volumes. Red lines show the distribution of fixed effects before adjusting multivariable models for institutional or surgeon volumes. Neither the variation between institutions nor the variation between surgeons changed substantially after adjusting for volumes.

Discussion

In this retrospective study of almost 3,000 infants undergoing stage 1 palliation at tertiary pediatric hospitals (defined as a RACHS-1 risk category six operation), we found that institutional volume was inversely associated with mortality, postoperative length of stay, and costs, but that surgeon volume was not. We further found that neither institutional nor surgeon volumes explained much of the wide variation in outcomes and resource utilization that exists between institutions and between surgeons.

Institutional volume has consistently been shown to be inversely associated with mortality after congenital heart surgery, particularly for the most complex procedures.3–10 It stands to reason that there might also be institutional economies of scale and other improvements in efficiency that result in shorter lengths of stay and reduced costs for these institutions. Exploratory analyses of costs per day suggest that the majority of the cost savings is derived from the shortened hospital stays.

Under a practice-makes-perfect theory, it has often been hypothesized that patients of higher volume surgeons have better clinical outcomes and require fewer resources. Our findings do not support this hypothesis. The effects of individual surgeon volume vis-à-vis institutional volume for stage 1 palliation in our study might make sense when considered in light of the physiologic effect of this operation. Procedures such as the arterial switch and interrupted aortic arch repair are operations that restore normal physiology if done correctly. On the other hand, even a perfectly executed stage 1 palliation is vulnerable to post-operative changes (both iatrogenic and physiologic) that might impact outcomes more than the (admittedly necessary) perfect technical execution of a stage 1 repair. Consequently, institutional factors such as the breadth of experience of nurses and cardiac intensivists might come to play in more significant ways for stage 1 palliation than for other biventricular repairs, where surgical expertise (and volume) might exhibit comparatively larger roles in determining outcomes.

The existing literature on the surgeon-volume to mortality relationship for stage 1 palliation is somewhat inconsistent. In 2012, using The Society of Thoracic Surgeons-Congenital Heart Surgery Database, Hornik et al. found an inverse association between surgeon volume and mortality for neonates with single ventricles undergoing the Norwood operation.13 Other studies have found no such association. In 2005, Checchia et al., using the PHIS database, found no association between surgeon volumes and outcomes in the late 1990s (1998–2001).11 In 2010, Karamlou et al., using a dataset derived from Congenital Heart Surgeons Society multi-institutional studies, found significant associations between surgeon volumes and mortality for infants with either transposition of the great arteries or interrupted aortic arch, but no significant association between surgeon volumes and mortality for children with single ventricles undergoing stage 1 palliation.14 Finally, in 2012, Tabbutt et al., in a secondary analysis of the Single Ventricle Reconstruction Trial (a prospective randomized trial assessing the effects of shunt type on stage 1 palliation outcomes), found that, while surgeon volume was significantly associated with mortality in univariable analyses, it was not associated with mortality after adjusting for institutional volume.15 There are no previous data regarding the effects of surgeon volume on resource utilization.

One of the concerns of using administrative data for this type of study is that one is only able to control for a limited set of patient characteristics. Details on anatomic complexity are typically not available. We, therefore, conducted extensive secondary analyses to assess the possibility of incomplete risk adjustment. More specifically, we wanted to assess the possibility that higher volume surgeons might routinely select (or be assigned) more challenging cases, whose differences are not captured by the variables available in the PHIS database; failure to adjust for these differences, could make the outcomes of surgeons performing these more complex cases appear worse than their peers. Our analyses suggest that it is unlikely that unmeasured differences in surgeon-specific case-mix exert significant effects on our results. First, when adding incrementally all of the patient characteristics measurable within the dataset, minimal change was seen in the point estimates for the magnitude of the associations between volumes and any of the measured outcomes. Second, in exploratory analyses individual surgeons were added as fixed effects to our models, which also generated minimal change in the point estimates for the effects of institutional and surgeon volumes on outcomes (data not shown). This statistical technique controls for unmeasured differences in surgeon-specific case-mix not included in the measured covariates. Third, the addition of surgeon volumes to our models explained almost none of the wide variation observed between surgeons.

The PHIS database, the Congenital Heart Surgeons Society dataset, and the Single Ventricle Reconstruction Trial include primarily tertiary pediatric hospitals. In contrast, The Society of Thoracic Surgeons-Congenital Heart Surgery Database also captures data from non-tertiary care centers. We hypothesize, therefore, that the differences in the existing literature might be the result of differences in the individual institutions captured within the databases, rather than differences in database structure. While surgeon volumes might predict outcomes for some procedures at some institutions, they might be less important than differences in perioperative care for children at tertiary children’s hospitals undergoing stage 1 palliation.

Also of note, repeating our analyses using methodology similar to that employed by Hornik et al., and including only patients operated in or before 2009 (as was done in their study), resulted in point estimates for the magnitude of the coefficients for surgeon volumes that were similar to those in their paper (although, in our data, these estimates still did not meet statistical significance). This raises the possibility that surgeon volume might have been a more important factor for children undergoing stage 1 palliation in a previous era, with institutional factors taking precedence as cumulative experience with this procedure has grown.

Conclusions

In summary, increased institutional—but not surgeon—volumes are associated with reduced mortality, postoperative length of stay, and costs for infants undergoing stage 1 palliation at tertiary pediatric hospitals. Neither significantly explains the wide variation in both clinical outcomes and resource utilization between institutions and between surgeons. As we strive to improve care for this high-risk population, further investigations are needed to determine more accurate markers of quality and to identify appropriate targets for future improvement.

Acknowledgements

None

Financial Support

Dr. Anderson received grant support for this study from the Andrew King Research Award from Colin’s Kids, Inc. This publication was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1 TR000040, formerly the National Center for Research Resources, Grant Number UL1 RR024156. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of Colin’s Kids or the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None

References

- 1.Robbins JM, Bird TM, Tilford JM, et al. Hospital Stays, Hospital Charges, and In-Hospital Deaths Among Infants with Selected Birth Defects--United States, 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean PN, Hillman DG, McHugh KE, et al. Inpatient costs and charges for surgical treatment of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1181–e1186. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazzani LG, Marcin JP. Case volume and mortality in pediatric cardiac surgery patients in California, 1998–2003. Circulation. 2007;115:2652–2659. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins KJ, Newburger JW, Lock JE, et al. In-hospital mortality for surgical repair of congenital heart defects: preliminary observations of variation by hospital caseload. Pediatrics. 1995;95:323–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasquali SK, Li JS, Burstein DS, et al. Association of center volume with mortality and complications in pediatric heart surgery. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e370–e376. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sollano JA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Volume-outcome relationships in cardiovascular operations: New York State, 1990–1995. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:419–428. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70320-x. discussion 428–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welke KF, Diggs BS, Karamlou T, et al. The relationship between hospital surgical case volumes and mortality rates in pediatric cardiac surgery: a national sample, 1988–2005. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:889–896. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.077. discussion 889–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welke KF, O'Brien SM, Peterson ED, et al. The complex relationship between pediatric cardiac surgical case volumes and mortality rates in a national clinical database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:1133–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch JC, Gurney JG, Donohue JE, et al. Hospital mortality for Norwood and arterial switch operations as a function of institutional volume. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:713–717. doi: 10.1007/s00246-007-9171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasquali SK, Jacobs JP, He X, et al. The complex relationship between center volume and outcome in patients undergoing the Norwood operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1556–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.07.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Checchia PA, McCollegan J, Daher N, et al. The effect of surgical case volume on outcome after the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannan EL, Racz M, Kavey RE, et al. Pediatric cardiac surgery: the effect of hospital and surgeon volume on in-hospital mortality. Pediatrics. 1998;101:963–969. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hornik CP, He X, Jacobs JP, et al. Relative impact of surgeon and center volume on early mortality after the Norwood operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1992–1997. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karamlou T, McCrindle BW, Blackstone EH, et al. Lesion-specific outcomes in neonates undergoing congenital heart surgery are related predominantly to patient and management factors rather than institution or surgeon experience: A Congenital Heart Surgeons Society Study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:569–577. e561. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabbutt S, Ghanayem N, Ravishankar C, et al. Risk factors for hospital morbidity and mortality after the Norwood procedure: A report from the Pediatric Heart Network Single Ventricle Reconstruction trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:882–895. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K, Newburger JW, et al. Consensus-based method for risk adjustment for surgery for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:110–118. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.119064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keren R, Luan X, Localio R, et al. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:1155–1164. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, et al. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E99. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics using Stata. Stata Press, College Station, Tex. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobin J. Estimation of Relationships for Limited Dependent Variables. Econometrica. 1958;26:24–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miglioretti DL, Heagerty PJ. Marginal modeling of nonnested multilevel data using standard software. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:453–463. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neidell MJ, Cohen B, Furuya Y, et al. Costs of healthcare- and community-associated infections with antimicrobial-resistant versus antimicrobial-susceptible organisms. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:807–815. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]