Abstract

Stickler syndrome is a genetically heterogeneous disorder that affects the ocular, auditory, and musculoskeletal systems. Ocular-only variant of Stickler syndrome type 1 (OSTL1) is characterized by high risk of retinal detachment without systemic involvement and is caused by alternatively spliced exon 2 mutation of COL2A1. We report the cases of two Korean families with OSTL1 carrying likely pathogenic variants of COL2A1. All patients presented with membranous vitreous anomaly, peripheral retinal degeneration, and/or rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, but no systemic manifestations. By genetic analysis, two likely pathogenic non-exon 2 variants, c.2678dupC (p.Ala895Serfs*49) and c.3327+ 1G>C, were identified in COL2A1. Our results demonstrate that COL2A1 defects in OSTL1 are not confined to mutations in exon 2. Together with molecular data, ophthalmologists should consider genetic diagnosis of Stickler syndrome in patients with vitreous anomaly to prevent blindness from retinal detachment. To our knowledge, this is the first report of genetically confirmed OSTL1 in Korea.

Keywords: COL2A1, Mutation, Ocular-only variant, Stickler syndrome, Retinal detachment

INTRODUCTION

Stickler syndrome is a hereditary connective tissue disorder of collagen associated with ocular, orofacial, auditory, and musculoskeletal manifestations [1]. Patients with Stickler syndrome have a high risk (50-70%) of developing rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) because of retinal breaks [2,3]. Therefore, early diagnosis is important to prevent visual loss from RRD.

Stickler syndrome type 1 (STL1; MIM 108300) is caused by mutations in COL2A1, which is located on 12q13.11 and encodes type II collagen found in cartilaginous tissue and vitreous humor [1]. STL1 has characteristic membranous vitreous anomaly and presents with multi-system abnormalities [4]. Recently, the ocular-only variant of STL1 (OSTL1; MIM 609508) has been reported to have a high risk of RRD, but with minimal or absence of systemic involvement [1,5]. Mutations involving exon 2 of COL2A1 are characteristic of OSTL1 [2,5,6]. We report the first genetically confirmed cases of OSTL1 in Korea with two novel mutations in COL2A1.

CASE REPORT

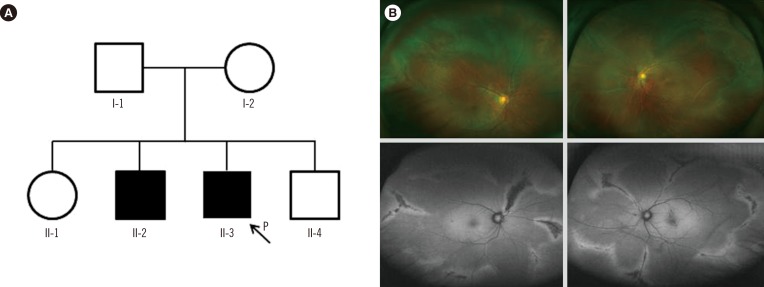

In family A, the proband (II-3, Fig. 1A) was a 39-yr-old man who visited the retina clinic for a regular check-up. His uncorrected visual acuity was 20/20 (right) and 20/25 (left). The fundus displayed radial perivascular atrophy, peripheral vitreous condensation, and a vitreous membrane (Fig. 1B). His older brother (II-2) had a history of retinal surgeries due to RRD in both eyes. His parents could not be examined but had no history of ocular disease, including retinal detachment, and there were no remarkable findings in other systems. The proband received prophylactic cryotherapy in both eyes to prevent RRD.

Fig. 1. (A) Pedigree of family A, harboring the c.2678dupC (p.Ala895Serfs*49) variant of COL2A1. (B) Wide-field fundus photographs (upper left and right) and fundus autofluorescence photographs (lower left and right) of individual II-3. Bilateral vitreous membrane and radial perivascular retinal degeneration are shown.

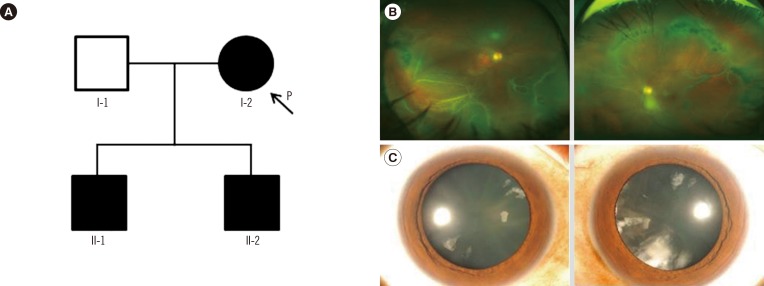

In family B, the proband (I-2, Fig. 2A) was a 57-yr-old woman who presented with sudden visual loss in the right eye. Her best-corrected visual acuity was finger counting in the right eye, and 20/20 in the left eye. Fundus examination revealed RRD with multiple retinal tears in the right eye (Fig. 2B). Vitreous membrane and radial perivascular atrophy were observed in both eyes. No systemic abnormalities were seen. Her first son (II-1; 35-yr) was myopic and had quadrantic lamellar cortical opacity (Fig. 2C). Radial perivascular atrophy was also seen; however, there were no retinal breaks. The second son (II-2) had history of retinal surgeries due to bilateral RRD. Prophylactic cryotherapy was performed in the non-detached eyes of the proband (I-2) and her first son (II-1).

Fig. 2. (A) Pedigree of family B, harboring the c.3327+1G>C variant of COL2A1. (B) Wide-field fundus photographs (upper left and right) of individual I-2. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with multiple retinal tears is shown in the right eye. Vitreous veil and peripheral perivascular atrophy were found in both eyes. (C) Anterior segment photographs (lower left and right) of individual II-1. Quadrantic lamellar cataract is shown in both eyes.

After obtaining informed consent, genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes of probands and their available family members. PCR and sequencing were performed by amplifying all coding exons of COL2A1 on the ABI 3730xl analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were analyzed by comparison with the reference sequence of COL2A1, NM_001844.4. In family B, the second son (II-2) of the proband refused the genetic test.

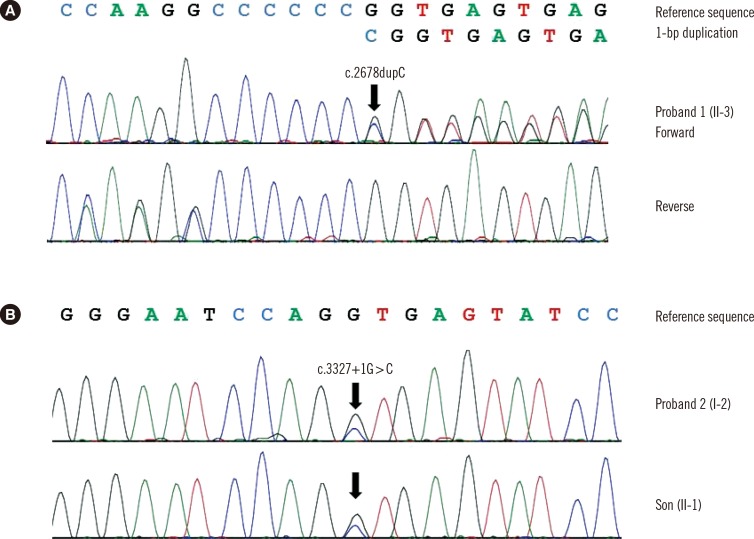

The proband of family A (II-3) was found to be heterozygous for a frameshift variant of COL2A1 (c.2678dupC; p.Ala895Serfs*49) with mutation in exon 40 (Fig. 3A). The other affected individual (II-2) refused the genetic test. In family B, the proband (I-2) was heterozygous for a novel variant (c.3327+ 1G>C) with mutation in intron 47 (Fig. 3B). The family study revealed that her first son (II-1) was heterozygous for the variant. Identified variants, c.2678dupC and c.3327+1G>C, were predicted to be truncating variants. These variants were absent from the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP), Exome Sequencing Project database, and in-house collection of 150 control exomes of Korean descent. We regarded them as likely pathogenic variants that may cause OSTL1 according to the standards and guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology [7].

Fig. 3. Molecular analyses of COL2A1 in two unrelated Korean families with ocular-only variant of Stickler syndrome type 1. (A) Individual II-3 of family A was heterozygous for 1-bp duplication of coding nucleotide 2678, which was predicted to result in frameshift at codon 895 and premature termination at the 49th amino acid in the new reading frame (c.2678dupC; p.Ala895Serfs*49). (B) Individual I-2 of family B and her son II-1 were heterozygous for the canonical +1 splice site variant (c.3327+1G>C) of COL2A1.

DISCUSSION

Here we present two cases of OSTL1 carrying two likely pathogenic variants of COL2A1. Although several Korean STL1 cases with COL2A1 mutations have been reported [8,9,10], these are all typical STL1 with musculoskeletal anomalies. In this study, all patients had ocular characteristics consistent with STL1, but systemic features were absent. This is the first genetically confirmed case of OSTL1 with non-exon 2 mutations in COL2A1 in the Korean population.

Most COL2A1 mutations in STL1 are spread throughout the gene and are predictive of premature termination, suggesting that the phenotype usually results from a quantitative defect in type II collagen synthesis because of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay [11]. Two different COL2A1 transcripts resulting from alternative splicing of exon 2 have been reported [12]. NM_001844.4 is the longer transcript, and it contains a large cysteine-rich domain in the amino-propeptide encoded by exon 2, which is predominantly expressed in the vitreous body [13]. In contrast, the shorter transcript in which exon 2 is spliced out is predominantly expressed in adult cartilage. Therefore, mutations in exon 2 of COL2A1 have been considered to cause more damage in the eye than in other tissues.

However, we demonstrated that the OSTL1 is not confined to mutations in the alternative spliced exon 2. The first variant, c.2678dupC, is located in exon 40; it has been previously reported in one Caucasian patient with STL1 [11]. Although clinical information was not provided in that study, c.2678dupC could contribute to the ocular phenotype on the basis of our case report. The second variant, c.3327+1G>C, is located within the consensus splice site in intron 47. Richards et al. [14] also reported a COL2A1 splicing mutation involving intron 51 in an OSTL1 patient, suggesting that tissue-specific missplicing could be a mechanism.

Recent studies showed that preventive treatment can significantly reduce the risk of RRD [15,16]; patients who did not receive prophylaxis had a 5-fold increased risk of RRD compared with those who received cryotherapy [16]. Therefore, high suspicion and genetic diagnosis for Stickler syndrome is important, given the emerging subgroup of OSTL1 with a high risk of RRD.

In conclusion, we identified two likely pathogenic variants of COL2A1, resulting from non-exon 2 mutations, which cause OSTL1. Clinicians should consider genetic diagnosis of OSTL1 in patients with vitreous anomaly to prevent blindness.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families for participation in this study. This work was supported by a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI13C1826) and Collaborative Genome Program for Fostering New Post-Genome industry through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (NRF-2014M3C9A 2064620).

Footnotes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Snead MP, McNinch AM, Poulson AV, Bearcroft P, Silverman B, Gomersall P, et al. Stickler syndrome, ocular-only variants and a key diagnostic role for the ophthalmologist. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:1389–1400. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards AJ, Martin S, Yates JR, Scott JD, Baguley DM, Pope FM, et al. COL2A1 exon 2 mutations: relevance to the Stickler and Wagner syndromes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:364–371. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stickler GB, Hughes W, Houchin P. Clinical features of hereditary progressive arthro-ophthalmopathy (Stickler syndrome): a survey. Genet Med. 2001;3:192–196. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liberfarb RM, Levy HP, Rose PS, Wilkin DJ, Davis J, Balog JZ, et al. The Stickler syndrome: genotype/phenotype correlation in 10 families with Stickler syndrome resulting from seven mutations in the type II collagen gene locus COL2A1. Genet Med. 2003;5:21–27. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parma ES, Körkkö J, Hagler WS, Ala-Kokko L. Radial perivascular retinal degeneration: a key to the clinical diagnosis of an ocular variant of Stickler syndrome with minimal or no systemic manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:728–734. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01646-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAlinden A, Majava M, Bishop PN, Perveen R, Black GC, Pierpont ME, et al. Missense and nonsense mutations in the alternatively-spliced exon 2 of COL2A1 cause the ocular variant of Stickler syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:83–90. doi: 10.1002/humu.20603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HY, Choi MS, Seong MW, Park SS, Park SK. A case of familial Stickler Syndrome in a newborn with COL2A1 gene mutation. Korean J Perinatol. 2014;25:100–104. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J, Jung CW, Kim GH, Lee BH, Choi JH, Yoo HW. A case of Stickler syndrome type I caused by a novel variant of COL2A1 gene. J Genet Med. 2011;8:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park DK, Kim SH, Lee BH, Kim GH, Yoo HW, Park MJ. A case of type 1 Stickler syndrome caused by a novel mutation in COL2A1. Korean J Med. 2014;87:738–742. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoornaert KP, Vereecke I, Dewinter C, Rosenberg T, Beemer FA, Leroy JG, et al. Stickler syndrome caused by COL2A1 mutations: genotype-phenotype correlation in a series of 100 patients. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:872–880. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan MC, Sandell LJ. Differential expression of a cysteine-rich domain in the amino-terminal propeptide of type II (cartilage) procollagen by alternative splicing of mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10334–10339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishop PN, Reardon AJ, McLeod D, Ayad S. Identification of alternatively spliced variants of type II procollagen in vitreous. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:289–295. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards AJ, Laidlaw M, Whittaker J, Treacy B, Rai H, Bearcroft P, et al. High efficiency of mutation detection in type 1 stickler syndrome using a two-stage approach: vitreoretinal assessment coupled with exon sequencing for screening COL2A1. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:696–704. doi: 10.1002/humu.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ang A, Poulson AV, Goodburn SF, Richards AJ, Scott JD, Snead MP. Retinal detachment and prophylaxis in type 1 Stickler syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fincham GS, Pasea L, Carroll C, McNinch AM, Poulson AV, Richards AJ, et al. Prevention of retinal detachment in Stickler syndrome: the Cambridge prophylactic cryotherapy protocol. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1588–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]