Abstract

The Korean Society of Nephrology (KSN) launched the official end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patient registry in 1985, and an Internet online registry program was opened in 2001 and revised in 2013. The ESRD Registry Committee of KSN has collected data on dialysis therapy in Korea through the online registry program in the KSN Internet website. The status of renal replacement therapy in Korea at the end of 2012 is described in the following. The total number of ESRD patients was 70,211 at the end of 2012, which included 48,531 hemodialysis (HD) patients, 7,552 peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients, and 14,128 functioning kidney transplant (KT) patients. The prevalence of ESRD was 1,353.3 patients per million population (PMP), and the distribution of renal replacement therapy among ESRD patients was as follows: HD, 69.1%; PD, 10.8%; and KT, 20.2%. The number of new ESRD patients in 2012 was 11,742 (HD, 8,811; PD, 923; and KT, 1,738; the incidence rate was 221.1 PMP). The primary causes of ESRD were diabetic nephropathy (50.6%), hypertensive nephrosclerosis (18.5%), and chronic glomerulonephritis (18.1%). The mean urea reduction ratio was 67.9% in male and 74.1% in female HD patients. The mean Kt/V was 1.382 in male and 1.652 in female HD patients. The 5-year survival rates of male and female dialysis patients were 70.6% and 73.5%, respectively.

Keywords: End-stage renal disease, Hemodialysis, Korea, Peritoneal dialysis

Introduction

The Korean Society of Nephrology (KSN) has the largest continuous end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patient registry, established in 1985, in which all KSN members are participating voluntarily: the “Insan Prof. Min Memorial ESRD Patient Registry.”

The objectives and importance of the patient registry and statistical evaluation of ESRD can be summarized as follows: (1) to estimate the numbers and distributions of target therapy patients by a dialysis specialist group (KSN); (2) to know the characteristics of ESRD and dialysis therapy, and its complications or results based on scientific evidence; and (3) to improve the quality of dialysis therapy, and provide information on socioeconomic health administration and the future health plan.

In 2013, because vascular access and dialysis quality became more important, KSN ESRD Committee has revised the online registry program. Newly included items were vascular access, dialysate components, calcium and phosphorous control, and rehabilitation status [1].

Data collection method

The ESRD Registry Committee of KSN has collected data on dialysis centers and patients through an online registry program on the KSN Internet website (http://www.ksn.or.kr) launched in 2001 and revised the program in 2013. The program also has a graphic evaluation function of dialysis adequacy [Kt/V and normalized protein catabolic rate (nPCR)] and a peritoneal equilibrium test. For ensuring the security of patients’ personal information, the program was accessible only to designated dialysis staff with a hospital code and password. Information on nonresponding dialysis centers was collected through questionnaires sent by mail.

Data on dialysis therapy in Korea

Prevalence and incidence of ESRD in Korea

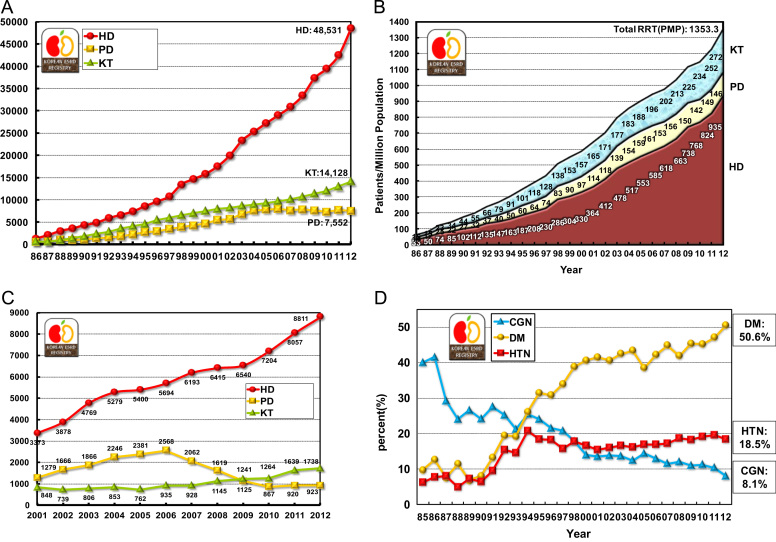

At the end of 2012, in Korea, the number of overall ESRD patients was 70,211, and that of ESRD patients under maintenance hemodialysis (HD), peritoneal dialysis (PD), and with functioning transplanted kidney were 48,531, 7,552, and 14,128, respectively. The prevalence per million population (PMP) was 935.4 for HD, 145.6 for PD, 272.3 for kidney transplantation (KT), and 1,353.3 for overall ESRD (Figs. 1A, 1B). These ESRD prevalence rates are slightly higher than those in most European countries, but about 60% of those in the United States and about 40% of those in Japan, according to the international comparison data of the annual United States renal data report [2], [3], [4]. The annual increase in the prevalence rate was about 10% during 2000–2012.

Figure 1.

Prevalence and incidence of end-stage renal replacement therapy in Korea. The number of patients with renal replacement therapy at the end of each year (A); point prevalence of renal replacement therapy (B); patients starting renal replacement therapy each year (C); and three major causes of end-stage renal disease (D). CGN, chronic glomerulonephritis; DM, diabetic nephropathy; HD, hemodialysis; HTN, hypertensive nephrosclerosis; KT, kidney transplantation; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PMP, patient numbers per million population; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

The number of new patients undergoing renal replacement therapy in 2012 was 11,472 (221.1 PMP). The number of new ESRD patients with HD, PD, and KT were 8,811 (169.8 PMP), 923 (17.8 PMP), and 1,738 (33.5 PMP), respectively (Fig. 1C). The number of new patients with PD has been decreasing since 2007, whereas those with HD and KT have been increasing continuously; this is consistent with the trend observed in the United States [2].

The most common causes of ESRD in new patients were diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive nephrosclerosis, and chronic glomerulonephritis (50.6%, 18.5%, and 8.1%, respectively; Table 1). Among these three underlying diseases, the incidence of diabetic nephropathy increased rapidly during 1990–2000 (Fig. 1D). The proportion of diabetic nephropathy in ESRD patients in Korea was one of the highest in the world, which was similar to some Asian countries and the United States [2].

Table 1.

Causes of end-stage renal diseases in new patients

| Causes | % |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1994 | 1996 | 1998 | 2000 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 25.3 | 25.5 | 21.6 | 17.9 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 12.5 | 13.0 | 12.1 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 10.4 | 8.1 |

| Not histologically confirmed | 19.7 | 20.4 | 16.7 | 13.6 | 10.6 | 10.0 | 8.6 | 9.0 | 8.2 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 4.5 |

| Histologically confirmed | 5.6 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 19.5 | 26.1 | 30.8 | 38.9 | 40.7 | 40.7 | 43.4 | 42.3 | 41.9 | 45.4 | 45.2 | 47.1 | 50.6 |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 15.4 | 20.8 | 18.3 | 17.8 | 16.6 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 16.9 | 18.7 | 18.3 | 19.2 | 19.6 | 18.5 |

| Cystic kidney disease | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Renal tuberculosis | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Pyelo/interstitial nephritis | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Drugs or nephrotoxic agents | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Lupus nephritis | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Gouty nephropathy | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Hereditary nephropathy | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Kidney tumor | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Other | 4.1 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 6.8 |

| Uncertain | 28.6 | 17.8 | 15.9 | 16.6 | 20.2 | 19.0 | 17.8 | 17.5 | 17.6 | 16.0 | 15.3 | 14.3 | 11.4 |

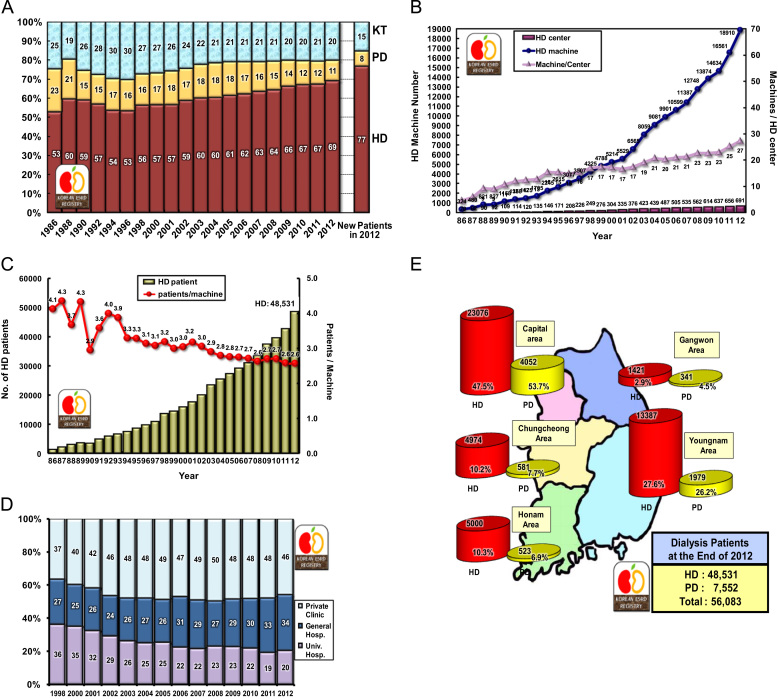

Renal replacement therapy modalities

Approximately 77% of new ESRD patients in 2012 started HD as their initial renal replacement therapy, whereas approximately 8% started PD. The prevalence rates of HD, PD, and KT were 69%, 11%, and 20%, respectively (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Renal replacement therapy modalities. Proportion of renal replacement modalities (annual prevalence and incidence in 2012) (A); the numbers of hemodialysis centers and hemodialysis machines (B), and hemodialysis patients and hemodialysis patients per hemodialysis machine (C); percent distribution of hemodialysis patients according to dialysis center classification (D); and regional distribution of dialysis patients in Korea (E). HD, hemodialysis; KT, kidney transplantation; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

The numbers of HD centers and HD machines have also been increasing rapidly in Korea. At the end of 2012, Korea had 691 HD centers and 18,901 HD machines (Fig. 2B). The ratio of machines per center was about 27, and that of patients per machine was 2.6 (Fig. 2C). Approximately one-third of maintenance HD patients were admitted to university hospitals in the late 1990s, but currently, about 46% of HD patients are treated in private dialysis clinics (Fig. 2D).

An analysis of the distribution of ESRD patients according to the zones in Korea showed that approximately 50% of HD patients and more than 50% of PD patients were located in the capital area (Fig. 2E).

Dialysis patient demographics

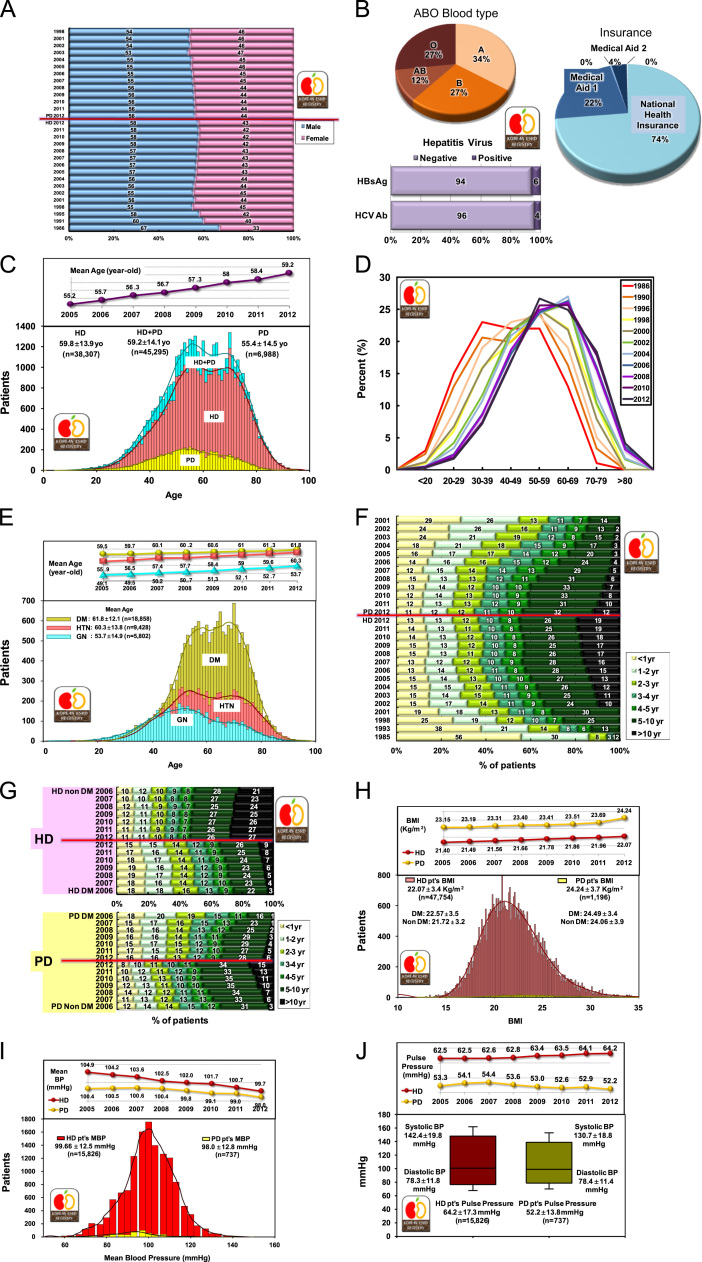

The gender ratio of dialysis patients was 57.5% male and 42.5% female in HD therapy and 56.1% male and 43.9% female in PD therapy (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Dialysis patient demographics. Gender ratio of HD and PD patients according to year (A); ABO blood type and hepatitis virus of HD and PD patients (B); age distribution of dialysis patients according to dialysis modalities (C), years (D), and underlying diseases (E); duration of maintenance HD and PD versus percent of estimated patient number according to year (F); duration of dialysis maintenance in diabetic and nondiabetic patients (G); distribution of BMI (H) and mean blood pressure (I) in HD and PD patients (blood pressure is higher in HD patients than in PD patients); and systolic and diastolic blood pressures with pulse pressure in HD and PD patients (J). BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; DM, diabetic patients; HD, hemodialysis; HTN, hypertensive nephrosclerosis; GN, glomerulonephritis; MBP, mean blood pressure; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

The ABO blood type distribution of dialysis patients was type A, 34%; type B, 27%; type AB, 12%; type O, 27%, which was not different from the general population. Hepatitis B virus antigen was positive in 6% of dialysis patients and hepatitis C virus antibody in 4% (Fig. 3B).

The mean age of dialysis patients was 59.2±14.1 years. The age distribution of dialysis patients showed two peaks, one at the age of 50 years and the other at the age of 65 years (Fig. 3C), indicating that at least two or more different disease groups are present among ESRD patients. The age distribution according to year since 1986 showed that the peak age has been shifting to older age and the current peak age is in the 60s (Fig. 3D). The percentage of dialysis patients aged more than 65 years increased to up to 37.5% of overall dialysis patients in 2012.

The age distribution according to underlying diseases showed that the peak age of chronic glomerulonephritis was 53.7 years and that of diabetic nephropathy was 61.8 years (Fig. 3E).

About 45% of HD patients and 44% of PD patients had been undergoing dialysis for more than 5 years; these percentages had increased from 30% and 14%, respectively, in 2001 (Fig. 3F).

Approximately 53% of nondiabetic HD patients had been undergoing dialysis for more than 5 years, whereas only 35% of diabetic HD patients had been undergoing dialysis for the same period. Similarly, approximately 49% of nondiabetic PD patients and 34% of diabetic PD patients had been undergoing dialysis for more than 5 years (Fig. 3G).

The mean body mass index was 22.1±3.4 kg/m2 in HD patients and 24.2±3.7 kg/m2 in PD patients; this showed a steady increase in both HD and PD groups. In HD patients, the mean body mass index was 22.6±3.5 kg/m2 in diabetic patients and 21.7±3.2 kg/m2 in nondiabetic patients (Fig. 3H).

The mean blood pressures were similar between HD and PD patients (99.7±12.5 mmHg and 98.0±12.8 mmHg, respectively; Fig. 3I), but the pulse pressure was much higher in HD patients than in PD patients (64.2 mmHg vs. 52.2 mmHg, Fig. 3J). Although the blood pressure of dialysis patients is decreasing, the pulse pressure of HD patients is increasing; this might be associated with the risk of cardiovascular morbidity.

Characteristics of HD, PD, and erythropoietin therapy

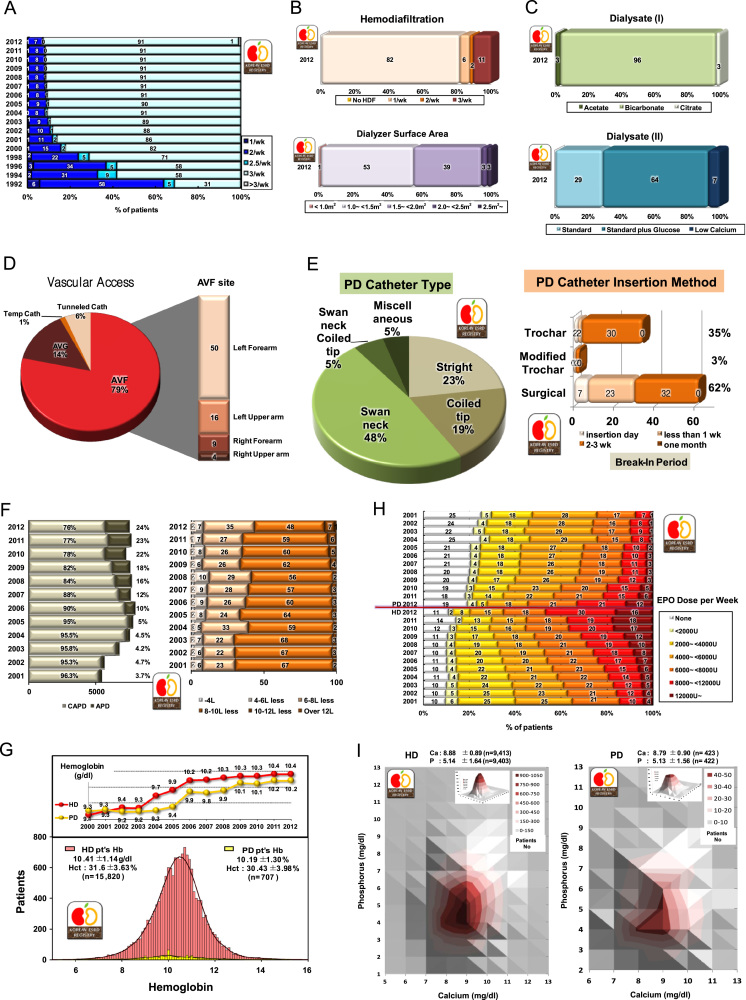

HD frequency, dialyzer, and dialysate

Most HD patients received dialysis three times per week (Fig. 4A) since 2000 (91.3% in 2012). Hemodiafiltration therapy was performed in 11% of HD patients, but 53% of HD patients received dialysis with a dialyzer having a surface area of less than 1.5 m2 (Fig. 4B). Mostly bicarbonate and standard calcium (3.0 mEq/L) with glucose dialysate were used (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Characteristics of HD, PD, and erythropoietin therapy. Frequency of hemodialysis per week (A); percent of HDF-applied patients and dialyzer membrane surface area (B); hemodialysis dialysate (C); vascular access for HD (D); PD catheter type and PD catheter insertion methods (E); Distribution of peritoneal dialysis types and doses (percentage) (F); changes in hemoglobin level in dialysis patients, HD versus PD (note the increase of hemoglobin in HD patients) (G); percent distribution of erythropoietin doses prescribed for HD and PD patients (H); distribution of patients numbers according to calcium and phosphorous levels (I); PTH levels of HD and PD patients (x-axis is on nature logarithmic scale) (J); phosphate binders and PTH control medications (K); distribution of URR in hemodialysis patients (L); dialysis adequacy parameters (nPCR and spKT/V) in HD patients (M); dialysis adequacy parameters (spKt/V) in diabetic and nondiabetic HD patients (N); and distribution of patient numbers according to nPCR and spKt/V in HD patients (O) and according to nPNA and Kt/V in PD patients (P). APD, automated peritoneal dialysis; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; EPO, erythropoietin; Hct, hematocrit; HD, hemodialysis; HDF, hemodiafiltration; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate; nPNA, normalized protein nitrogen appearance; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PTH, parathyroid hormone; spKt, single-pool Kt/V; URR, urea reduction ratio.

Vascular access for HD

Of the HD patients, 79% had autologous arteriovenous fistula, of which 50% was in the left forearm, and 14% had graft fistula (Fig. 4D).

PD catheter and dialysate dose

Of the PD patients, 48% had swan neck PD catheters and 23% had straight PD catheters. The PD catheter was inserted surgically in 62% of PD patients. The break-in period after catheter insertion was mostly 2–3 weeks, for both surgical and trochar insertions (Fig. 4E). Automated PD therapy was applied to 24% of PD patients, and a PD dialysate volume of 10–12 L/day was used in 48% of PD patients (Fig. 4F).

Anemia and erythropoietin therapy

In 2012, the mean hemoglobin level of HD patients was 10.4±1.1 g/dL and that of PD patients was 10.2±1.3 g/dL (Fig. 4G). Although, theoretically, PD patients have a lower prevalence of anemia than HD patients, the recent use of erythropoietin therapy has increased hemoglobin levels in HD patients more than in PD patients. This therapeutic result is shown clearly in Figs. 4G and 4H: Of the HD patients, 46% were injected with 8,000 or more units of erythropoietin per week, whereas only 33% of PD patients were injected with this level of erythropoietin and 19% of PD patients were not injected with erythropoietin. The significant increase in the hemoglobin level of both dialysis patients in 2004 and 2005 was due to an increase in the reimbursement level of hemoglobin by the National Health Insurance.

Laboratory data and medications

The distribution of patient numbers according to calcium and phosphorous levels is shown in Fig. 4I; the mean total calcium and phosphorous levels in HD patients were 8.88±0.89 mg/dL and 5.14±1.64 mg/dL, respectively. Serum intact parathyroid hormone level of dialysis patients has been shown as a nature logarithmic scale distribution (Fig. 4J).

Calcium bicarbonate or acetate was used in 67% HD patients as a phosphate binder, and 24% of HD patients received vitamin D therapy (Fig. 4K).

The mean serum albumin, creatinine, cholesterol, uric acid, and HbA1c levels in HD patients were 3.9 g/dL, 9.68 mg/dL, 144.0 mg/dL, 7.22 mg/dL, and 6.92%, respectively.

Dialysis adequacy

The mean urea reduction ratio was 67.9% in male and 74.1% in female HD patients (Fig. 4L). This gender difference of dialysis adequacy resulted from the use of similar dialysis doses in men and women despite a body mass difference between the genders. The overall mean urea reduction ratio was 70.5±7.1%; which showed a steady increase.

The average nPCR and single-pool Kt/V were 0.98±0.28 and 1.49±0.29, respectively. Similar to the urea reduction ratio, both these values were higher in women than in men (Fig. 4M). Single-pool Kt/V was higher in nondiabetic patients than in diabetic patients, presumably because of the quality of vascular access for dialysis (Fig. 4N). The recent protein catabolic rate showed a slight decrease, presumably because of the increase in the proportion of elderly dialysis patients.

Distribution of patient numbers according to nPCR and single-pool Kt/V in case of HD patients and that according to nPNA and PD Kt/V in case of PD patients are shown in Figs. 4O and 4P.

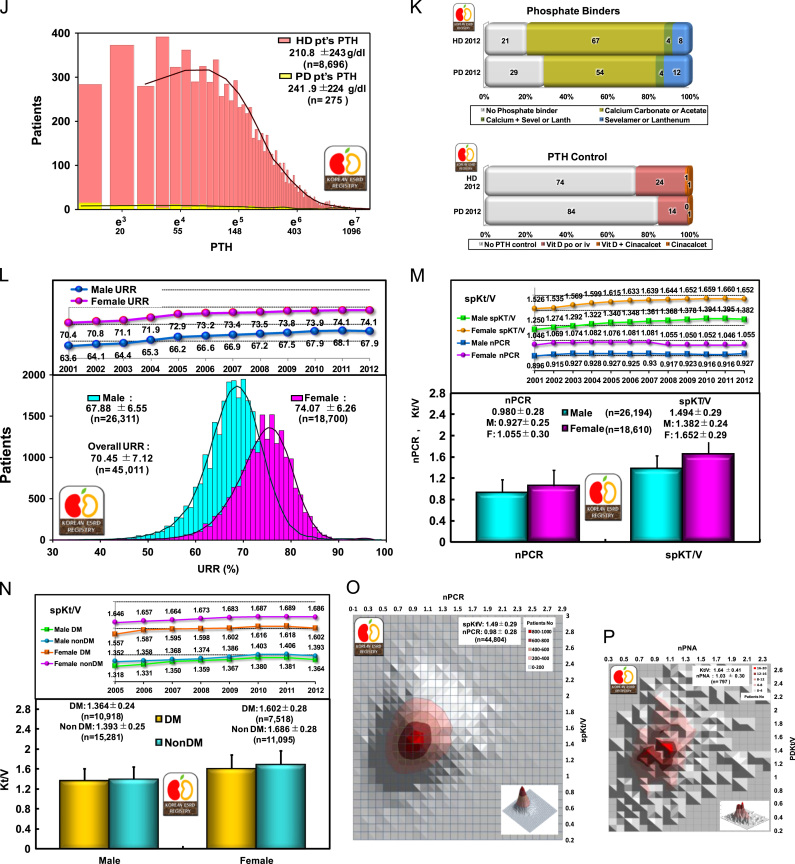

Rehabilitation, morbidities, causes of death, and survival rates of dialysis patients

Rehabilitation

Of the PD patients, 33% had full-time jobs and 24% part-time jobs, but only 24% of HD patients had full-time jobs in 2012 (Fig. 5A). This means that a higher rehabilitation rate was achieved in PD patients.

Figure 5.

Rehabilitation, morbidities, causes of death, and survival rates of dialysis patients. Rehabilitation status of HD and PD patients in 2012 (A); comparison of causes of death in HD versus PD patients in 2001–2012 (B); overall survival of dialysis patients registered since 2001 (C); survival of HD and PD patients since 2001 (D); and patient survival according to underlying diseases since 2001 (E). DM, diabetic nephropathy; GN, glomerulonephritis; HD, hemodialysis; HTN, hypertensive nephrosclerosis; Misc, miscellaneous; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Comorbidity

The most common complications (51.2%) in HD patients were vascular diseases, which included hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, and other vascular diseases (Table 2). Furthermore, 60.7% of PD patients had vascular diseases, and the infectious complication rate was higher in PD patients (8.5%) than in HD patients (5.0%).

Table 2.

Comorbidities of dialysis patients in 2012

| Variables | Hemodialysis patients (%) | Peritoneal dialysis patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | 18.0 | 14.2 |

| Coronary artery disease | 9.3 | 7.6 |

| Congestive heart failure | 4.3 | 5.0 |

| Pericardial effusion | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Arrhythmia | 3.8 | 1.1 |

| Vascular | 51.2 | 60.7 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 3.7 | 4.2 |

| Hypertension | 45.9 | 55.3 |

| Other vascular disease | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Infection | 5.0 | 8.5 |

| Pneumonia | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Tuberculosis | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| Peritonitis | 0.4 | 3.1 |

| Herpes zoster | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Access/exit site infection | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Other infections | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Liver disease | 7.9 | 4.6 |

| Hepatitis B | 4.6 | 3.4 |

| Hepatitis C | 2.9 | 0.8 |

| Congestive liver | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Hemochromatosis | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other liver diseases | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Gastrointestinal | 10.8 | 6.4 |

| Gastric ulcer | 2.3 | 1.0 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Constipation | 1.7 | 0.2 |

| Other gastrointestinal diseases | 6.3 | 4.9 |

| Miscellaneous | 7.0 | 5.6 |

| Malnutrition (Alb < 2.5 g/dL) | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Malignancy | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Hypertensive retinopathy | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Uremic dermatitis | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| Uremic neuritis | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| Uremic dementia | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Uremic ascites/pleural effusion | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Osteodystrophy | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| COPD and other pulmonary diseases | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Decubitus ulcer/DM foot | 1.0 | 0.9 |

Alb, serum albumin; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Causes of death

The causes of death in dialysis patients in a descending order of frequency were cardiac causes, infection, and vascular disease. The cause of death was unknown or miscellaneous in one-quarter of dialysis patients (Table 3, Fig. 5B). Some year-to-year variation was observed because of limitations in death reports.

Table 3.

Causes of death (%) in dialysis patients, 1994–2012⁎

| 1994–1996 | 1998 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | 27.4 | 27.4 | 26.9 | 31.7 | 30.7 | 33.7 | 31.7 | 35.1 | 29.5 | 31.1 | 32.7 | 33.9 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6.4 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 7.4 | 8 | 9.1 | 7.5 | 9.7 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 6.6 | 6.8 |

| Cardiac arrest, uremia associated | 13.7 | 13.7 | 11.2 | 11.7 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 10.8 | 11 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 11.0 | 11.1 |

| Cardiac arrest, other causes | 7.2 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 14.4 | 13 | 14.2 | 15.0 | 16.0 |

| Vascular | 17.2 | 17.2 | 22.7 | 19.5 | 17 | 16.5 | 17.8 | 16 | 15.9 | 13.3 | 14.1 | 13.0 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 14.3 | 14.3 | 15.1 | 14.5 | 12.3 | 11.5 | 13 | 12.2 | 11 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 7.9 |

| Pulmonary embolus | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| Gastrointestinal embolism | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Other vascular diseases | 0.9 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 1.9 |

| Infection | 13.5 | 13.5 | 17.8 | 20.5 | 20.1 | 18.8 | 20.2 | 19.5 | 21.9 | 22.6 | 23.1 | 24.5 |

| Pulmonary infection | 2.5 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 5.9 | 7.5 | 8.4 | 10.8 |

| Septicemia | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.9 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 8.9 | 11.7 | 9 | 10.4 | 10.7 | 9.7 | 8.9 |

| Tuberculosis | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Peritonitis | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Other infections | 2 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 2.9 | 4 | 4.5 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 3.0 |

| Liver disease | 3.4 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.8 |

| Liver failure due to hepatitis B | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| Liver failure due to other cause | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1 | 1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| Social | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 4.4 | 5.4 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 2.2 |

| Patient refused further treatment | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Suicide | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 3 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Therapy ceased for other reasons | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.3 |

| Miscellaneous | 32 | 32 | 23.7 | 21.3 | 24 | 24.2 | 24.8 | 24.3 | 27.1 | 27.3 | 24.7 | 23.6 |

| Cachexia | 2.9 | 2.9 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 4 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.1 |

| Malignant diseases | 2.1 | 2.1 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 6.4 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.7 |

| Accident | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| Uncertain | 25.8 | 25.8 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 12.3 | 13.2 | 13.4 | 14.9 | 16.8 | 18 | 14.5 | 13.3 |

Number of patients: 1994–1996, 981; 1998, 911; 2001, 761; 2003, 894; 2005, 1,256; 2006, 1,248; 2007, 1,531; 2008, 1,563; 2009, 1,727; 2010, 1,802; 2011, 1,828; 2012, 1,745.

Patient survival

The overall 1- and 5-year survival rates of dialysis patients were 95% and 72%, respectively (Fig. 5C). These survival rates were higher than those observed in the United States and Japan [2], [3], but the Korean survival rate was calculated only from the data of dialysis patients registered since 2001. The Korean ESRD Registry covers only about two-thirds of all dialysis patients in Korea because registry enrollment is voluntary.

The 5-year survival rate was higher in HD patients than in PD patients (72.6% vs. 68.3%; Fig. 5D), and the 5-year survival rate was higher for chronic glomerulonephritis patients than for diabetic patients (86.4% vs. 61.4%; Fig. 5E).

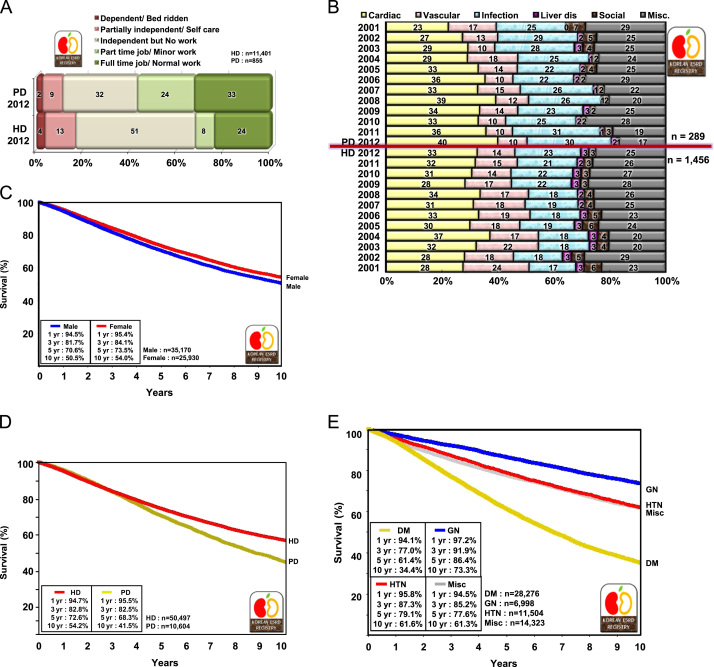

Kidney transplantation

In 2012, KT was performed in 1,783 cases, which included 768 deceased donors (Fig. 6). The KT rate was 37 cases per 1,000 dialysis patients, which was below the world average [2]. However, the waiting number has been increasing sharply, and 12,463 surviving dialysis patients were enrolled in the Korean Network of Organ Sharing waiting list at the end of 2012.

Figure 6.

Annual number of KTs in Korea (including data from the KONOS). Surviving KT waiting patient number at the end of each year. KONOS, Korean Network for Organ Sharing; KT, kidney transplantation.

Conclusion

The increasing proportion of elderly and diabetic patients in the Korean population has resulted in a rapid increase in the number of ESRD patients, which reached 1,353 PMP at the end of 2012. A high proportion of diabetic ESRD patients (50.6%) and a decrease in the proportion of PD patients were observed recently. Among ESRD patients, the proportion of HD has increased to 69%, PD decreased to 11%, and KT has remained at 20%. The adequacies of dialysis and anemia therapy have been improving steadily in Korea.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgments

The ESRD Registry Committee of the KSN thank all the medical doctors and nurses of dialysis centers in Korea for participating in this survey. We also thank FMC Korea, Boryung Pharm, Baxter Korea and Gambro Korea for sharing the data.

Footnotes

Most data in this article were presented at the 33rd autumn meeting of Korean Society of Nephrology, October 2013. Data from the Insan Memorial Dialysis Patient Registry by ESRD Registry Committee of Korean Society of Nephrology: Dong Chan Jin, Nam Ho Kim (Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea), Seoung Woo Lee (Inha University, Inchon, Korea), Jong Soo Lee (Ulsan University, Ulsan, Korea), Sung Ro Yoon (Kunyang University, Daejeon, Korea), and Byung Su Kim (The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea).

References

- 1.ESRD Registry Committee, Korean Society of Nephrology: Current renal replacement therapy in Korea 2012. Available at: http://www.ksn.or.kr [Date accessed: 1 October 2013]

- 2.United States' Renal Data System: Annual report of United States’ Renal Data System 2013. Available at: http://www.usrds.org/adr.htm [Date accessed: 1 October 2013]

- 3.Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy: An overview of regular dialysis treatment in Japan. Available at: http://www.jsdt.or.jp/ [Date accessed: 1 October 2013] (Japanese)

- 4.European Renal Association: European Dialysis and Transplantation Association Registry 2011. Available at: http://www.era-edta-reg.org/index.jsp [Date accessed: 1 October 2013]