Abstract

Oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP) exchanges cholesterol and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI-4P) at contact sites between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the trans-Golgi/trans-Golgi network. 25-Hydroxycholesterol (25OH) competitively inhibits this exchange reaction in vitro and causes the constitutive localization of OSBP at the ER/Golgi interface and PI-4P-dependent recruitment of ceramide transfer protein (CERT) for sphingomyelin synthesis. We used PI-4P probes and mass analysis to determine how OSBP controls the availability of PI-4P for this metabolic pathway. Treatment of fibroblasts or Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells with 25OH caused a 50–70% reduction in Golgi-associated immunoreactive PI-4P that correlated with Golgi localization of OSBP. In contrast, 25OH caused an OSBP-dependent enrichment in Golgi PI-4P that was detected with a pleckstrin homology domain probe. The cellular mass of phosphatidylinositol monophosphates and Golgi PI-4P measured with an unbiased PI-4P probe (P4M) was unaffected by 25OH and OSBP silencing, indicating that OSBP shifts the distribution of PI-4P upon localization to ER-Golgi contact sites. The PI-4P and sterol binding activities of OSBP were both required for 25OH activation of sphingomyelin synthesis, suggesting that 25OH must be exchanged for PI-4P to be concentrated at contact sites. We propose a model wherein 25OH activation of OSBP promotes the binding and retention of PI-4P at ER-Golgi contact sites. This pool of PI-4P specifically recruits pleckstrin homology domain-containing proteins involved in lipid transfer and metabolism, such as CERT.

Keywords: cholesterol, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), Golgi, lipid transport, 25-hydroxycholesterol, oxysterol binding protein, sphingomyelin

Introduction

The unique membrane composition of organelles is predicated on intrinsic lipid metabolism, as well as lipid trafficking to and from other membranes. In mammalian cells, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 is the primary but not exclusive site for de novo synthesis of lipid and sterols (1), which are then exported to other organelles. The limited aqueous solubility of lipids and sterols necessitates that transport from the ER and other organelles occurs in secretory vesicles or by lipid-binding proteins that mediate monomeric transfer by diffusional and/or membrane contact-site mechanisms (2). Unlike bulk transfer in secretory vesicles, binding proteins could mediate the site-specific transfer of their lipid cargo at opposing membranes. Alternatively, lipid-binding proteins may not be involved in transfer per se but instead regulate lipid-sensing or signaling pathways (3).

Approximately 0.2% of mammalian genomes encode proteins that are implicated in lipid transfer. A majority are proteins consisting of only a binding fold that accommodates a single hydrophobic ligand. A subset of lipid-binding proteins have additional protein- and lipid-interacting domains that mediate differential targeting to cellular organelles (4–6). The latter group is typified by the eukaryotic oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP) gene family whose 12 members share a conserved C-terminal OSBP-homology domain (OHD) that binds lipophilic ligands (7). The founding member of the family, OSBP, was identified in the 1980s based on high affinity binding of the side chain-hydroxylated sterol, 25-hydroxycholesterol (8). However, it is now apparent that OSBP and OSBP-related proteins (ORPs) bind a variety of ligands, including cholesterol, ergosterol, oxysterols, phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI-4P), and phosphatidylserine (PS) (9–12). Structural analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Osh4 and Osh3 complexed with PI-4P revealed ionic interactions between the phosphoinositol headgroup and two histidine residues at the entrance of the lipid binding pocket (13, 14). Because these histidine residues are conserved in all OSBP homologues, PI-4P binding is a core function. Most members of the OSBP family also have pleckstrin homology (PH) and two phenylalanines in an acidic tract domain that mediate interaction with phosphatidylinositol polyphosphate-enriched membranes and the ER, respectively. Thus OSBP/ORP transfer or signaling functions could occur at contact sites between closely apposed membranes.

Recent evidence suggests that OSBP/ORP and Osh proteins catalyze the exchange of cholesterol, ergosterol, PS, and PI-4P between membranes (14–17). In the case of OSBP, net transport of cholesterol from the ER to the Golgi apparatus is driven by exchange with PI-4P in the Golgi apparatus. PI-4P is then transported to the ER and dephosphorylated by the PI-4P phosphatase Sac1. The exchange of cholesterol and PI-4P by OSBP is a dynamic process that is envisioned to occur transiently at ER-Golgi contact sites through interaction of the PH domain with PI-4P and Arf1 and the two phenylalanines in an acidic tract domain with the ER-resident protein vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A (VAPA), respectively (18–20). In contrast, 25OH binding shifts OSBP from the ER or cytoplasm to Golgi-ER contact zones. Retention of OSBP at the ER-Golgi is interpreted as an inactive transport state caused by displacement of cholesterol or PI-4P by 25OH (9). However, when activated by 25OH at the ER-Golgi interface, 1) OSBP recruits ceramide transfer protein (CERT), leading to increased sphingomyelin synthesis in the Golgi apparatus (21); 2) OSBP recruits phosphatidylinositol/phosphatidylcholine transfer protein Nir2 (22); and 3) OSBP increases sterol-regulated PI4K IIα activity in a post-Golgi compartment, which is required for CERT recruitment and SM synthesis (23).

A feature of the countercurrent cholesterol transfer model is the displacement of PI-4P from OSBP by 25OH at the ER-Golgi membrane contact sites leading to increased PI-4P levels due to lack of transport to the ER for degradation (15). However, the relative affinity of OSBP for its ligands and the concentration of these ligands at contact sites are unknown, indicating the potential for more complex exchange reactions. With this in mind, exogenous PI-4P-specific probes and mass analysis were used to demonstrate that 25OH-dependent localization of OSBP at ER-Golgi contacts does not affect total PI-4P levels but causes a substantial redistribution of probe-accessible PI-4P pools. The establishment of a PH domain-accessible pool of PI-4P by OSBP would recruit proteins, such as CERT and Nir2, to the ER-Golgi interface.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture and Transfection

CHO-K1 cells stably expressing an OSBP-specific shRNA (CHO-shOSBP) or a non-targeting control shRNA (CHO-shNT) were cultured in DMEM with 5% FCS, proline (35 μg/ml), and blasticidin (1 μg/ml) (12). Routine monitoring by immunoblotting indicated >90% reduction in OSBP expression in CHO-shOSBP cells compared with the CHO-shNT controls (see Figs. 3 and 10). Primary human skin F8 fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM with 10% FCS. Recombinant OSBP, OSBP-H524A/H525A, OSBP-R109E/R110E, and OSBP-Δ432–435 (His-tagged on the C terminus) were expressed and purified from Sf21 cells by metal-affinity chromatography (12).

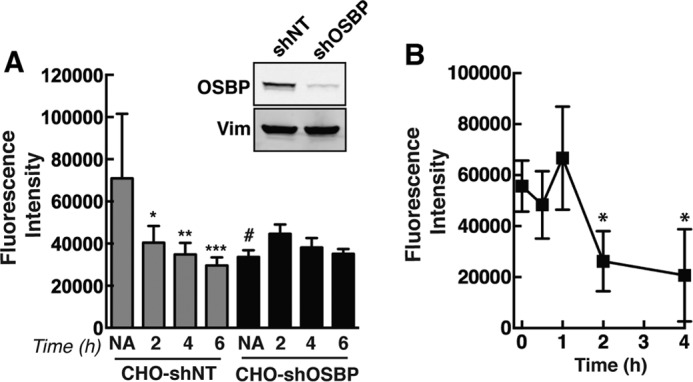

FIGURE 3.

PI-4P immunostaining is dependent on OSBP expression and cholesterol content. A, fluorescence intensity of PI-4P immunostaining was quantified in CHO-shNT and CHO-shOSBP cells that were treated with 25OH for up to 6 h. Results are the mean and S.D. of four experiments using 15–20 fields of cells (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.005; #, p < 0.05 compared with no addition (6-h solvent-treated) CHO-shNT cells). The inset shows an immunoblot of OSBP in control and knockdown CHO cells relative to vimentin (Vim) expression. NA, no addition. B, CHO-K1 cells were incubated with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (5 mm), and the fluorescence intensity of PI-4P immunostaining was quantified as described in A (*, p < 0.01 compared with untreated cells at 0 h).

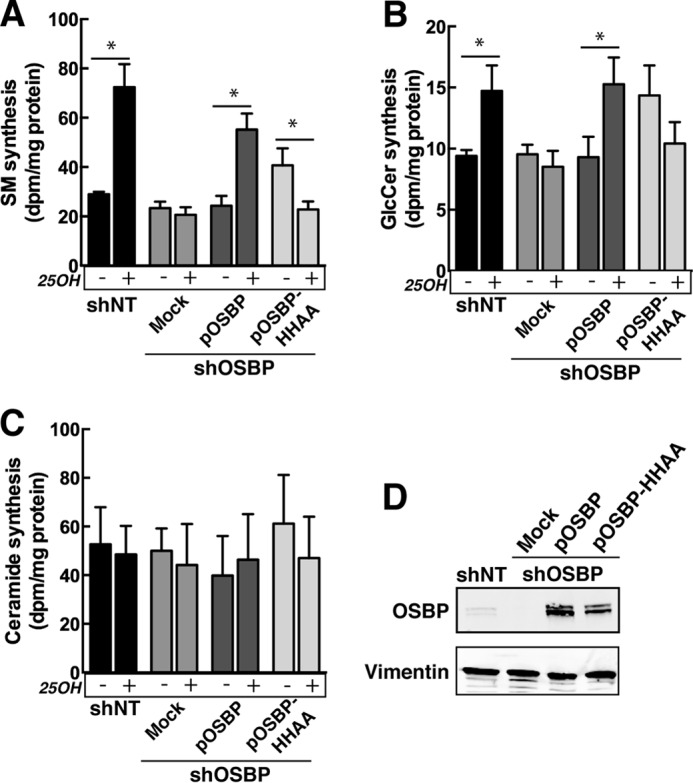

FIGURE 10.

Activation of SM and glucosylceramide synthesis by 25OH requires the PI-4P binding activity of OSBP. shOSBP cells were transiently transfected with empty vector (mock) or shRNA-resistant pOSBP or pOSBP-HH/AA for 48 h. Incorporation of [3H]serine into SM (A), GlcCer (B), and ceramide (C) was measured in solvent control and 25OH-treated cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Results are the mean and S.D. of three experiments. *, p < 0.05. D, immunoblot of OSBP expression in lysates of CHO-shNT and CHO-shOSBP cell expressing shRNA-resistant cDNAs.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Immunostaining of PI-4P was conducted as described (24). Briefly, cells cultured on glass coverslips were fixed with 2% (v/v) formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 150 mm NaCl and 10 mm phosphate, pH 7.4) for 10 min and permeabilized in PBS containing 12 μm digitonin and 100 mm glycine for 20 min. Coverslips were incubated with an anti-PI-4P IgM monoclonal antibody (Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City UT) in PBS containing 1% (w/v) BSA at 4 °C for 12–16 h, followed by an AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at 20 °C. Co-immunostaining for giantin, OSBP, or TGN46 was compatible with this method. PI-4P was detected on the plasma membrane by fixing cells in 4% (w/v) formaldehyde and 2% (w/v) glutaraldehyde and permeabilizing in 5% (v/v) goat serum and 0.5% (w/v) digitonin on ice. In experiments not involving PI-4P detection, cells were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100 at 4 °C prior to antibody incubation. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides with Mowiol 4-88. A Zeiss LSM510/Axiovert 200 M inverted microscope with a Plan-Apochromat ×100/1.40 NA oil immersion objective was used for confocal imaging. Wide field images were captured using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M fluorescence microscope with an Axiocam HRm CCD camera and a ×100/1.4 NA oil-immersion objective.

Fluorescent intensity of PI-4P immunostaining in cellular compartments was quantified using ImageJ software as described previously (25). Briefly, the “analyze particles” command was used to quantify intensity of 8-bit images of PI-4P-stained cells that were processed for background and threshold. To acquire Golgi and non-Golgi fluorescence intensity, a dilated mask was created from corresponding images of Golgi-specific markers (giantin or TGN46), overlaid on PI-4P images using the “image calculator” command, and quantified. Fluorescence intensity was normalized to the number of cells in each field.

mCherry-P4M (26) was used to visualize PI-4P in the Golgi apparatus of CHO cells by expression with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-Golgi (YFP fused to the N-terminal membrane domain of 1,4-glucosyltransferase, Clontech). Cells cultured in glass bottom dishes were mounted in the humidified temperature-controlled chamber of a Zeiss inverted microscope and imaged using a Yokogawa spinning disc confocal unit equipped with 488- and 561-nm laser/filter sets, an Axiocam Hrm CCD, and a ×63 (1.4 NA) oil immersion objective. For fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments (FRAP), cells were cultured and transfected as described above, and expression of YFP-Golgi was used to select Golgi-associated mCherry-P4M for bleaching. A region of interest in the Golgi was bleached with the 561-nm laser set at 80% intensity. Pre-and post-bleach images were acquired at 50-ms intervals with a 561-nm laser/filter sets and an Evolve Photonics CCD. Fluorescent recovery in the region of interest was corrected for background fluorescence and loss of total fluorescence, and the data were fit to a bottom-to-span single exponential association algorithm using GraphPad Prism (version 6.0).

The PH domain of OSBP-related protein (ORP4) fused to GFP (GFP-ORP4-PH) was used to detect Golgi PI-4P in transiently transfected CHO-shNT and CHO-shOSBP cells (27). Fluorescence intensity in the Golgi apparatus in fixed or living cells was quantified by ImageJ analysis as described above.

Quantitation of Phosphoinositides by Mass Spectrometry

Phosphoinositides in CHO cells and fibroblasts were quantified by the phosphate methylation method and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (28). Cells (1–2 × 105) were rinsed once with cold PBS and scraped in 0.5 ml of 1 m HCl into a polypropylene tube. A sample was removed for protein quantitation. Following centrifugation, cell pellets were resuspended in 170 μl of water, 750 μl of methanol/chloroform/water (0.5/0.25/0.25, v/v), and 1 ng of internal standard (C17:0/C20:4 PI-4P or C17:0/C20:4 PI-4,5P2 from Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) for 10 min at 20 °C. Chloroform (725 μl) and 2 m HCl (170 μl) were added, mixed, and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,500 × g. The lower phase was collected and washed once with upper phase mix (methanol, chloroform, 0.01 m HCl, 0.54:0.26:0.2, v/v). The organic phase was derivatized with 10 μl of 2 m trimethylsilyl diazomethane (Sigma) for 10 min at 20 °C and terminated with 6 μl of glacial acetic acid. Following two washes with 700 μl of methanol/chloroform/water (0.54:0.26:0.2, v/v), the organic phase was dried and redissolved in 80 μl of methanol and 20 μl of water. Lipid extracts were applied to a C4-reverse phase column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA), eluted with a 20–98% acetonitrile/water gradient (containing 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 15 μl/min, and infused into an ABSciex 4000 Qtrap mass spectrometer run in the positive ion mode. Multiple reaction monitoring was used to identify five different phosphatidylinositol monophosphate (PIP) and phosphatidylinositol diphosphate (PIP2) species based on fragmentation of selected parent ions into a characteristically charged diacylglycerol fragment and a second monoacylglycerol derivative that were used to identify the fatty acid composition of the parent ion. Response ratios were calculated from the integrated area ratios for the lipid species and internal standard and expressed relative to total cell protein.

[32P]Phosphate Labeling of PIP and PIP2

CHO-shNT and CHO-shOSBP cells were incubated for 2 h in phosphate-free DMEM containing 2% FCS, proline (35 μg/ml), with or without 25OH (6 μm). Cells then received [32P]phosphate (25 μCi/dish) to radiolabel phosphoinositides. After 6 h, cells were rinsed in PBS and scraped in 1 ml of 0.25 n HCl into a Teflon-sealed tube. Lipids were extracted into the solvent phase after addition of 3.8 ml of chloroform, methanol, 12 n HCl (2:4:0.1,v/v) and 1.2 ml of chloroform. After drying under nitrogen, lipid residues were resolved by thin layer chromatography in chloroform, methanol, 4 m ammonium hydroxide (90:70:20, v/v) with authentic PI-4P and PI-4,5P2 standards. Radioactivity co-migrating with standards was quantified by liquid scintillation counting and expressed relative to total cellular protein.

OSBP-dependent Activation of SM Synthesis

CHO-shNT or CHO-shOSBP cells were transfected with empty vector, pOSBP, or pOSBP-H524A/H525A for 48 h and then switched to serine-free medium containing 25-OH (6 μm) or ethanol solvent for 4 h. Cells were radiolabeled with [3H]serine (10 μCi/ml) for 2 h, harvested, and isotope incorporation into phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), PS, SM, ceramide, and glucosylceramide was quantified as described previously (21). [3H]Serine incorporation into lipids was expressed relative to total cellular protein.

Sterol and PI-4P Binding Activity of OSBP

The [3H]cholesterol and [3H]25OH binding activities of OSBP and OSBP-H524A/H525A was measured by the metal-affinity resin binding and charcoal-dextran methods, respectively (12). Specific binding was calculated by subtraction of total binding from that in the presence of a 40-fold excess of unlabeled sterol.

[32P]PI-4P was purified by thin layer chromatography of lipid extracts of HeLa cells that were radiolabeled with [32P]phosphate (5 mCi/ml) for 18 h (12). [32P]PI-4P (2,000–5,000 dpm) was mixed with phosphatidylcholine, PE, PS, lactosyl-PE, and PI-4P (58:20:10:10:2, mol/mol), dried under nitrogen, and rehydrated in liposome buffer (25 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 m EDTA, pH 7.4). Liposomes were prepared by extrusion of the lipid mixture through 200-nm filters and pre-cleared at 15,000 × g for 5 min. Recombinant OSBPs (0–200 pmol) were incubated with liposomes (10 nmol) and 3 μg of BSA in liposome buffer for 20 min at 25 °C in a volume of 80 μl. The reaction was terminated on ice, and Ricinus communis lectin was added for 5 min. Samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 15,000 × g, and radioactivity in the supernatant was quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Extraction was expressed as a percentage of total [32P]PI-4P input and corrected for extraction in the absence of OSBP.

Binding of recombinant OSBP to PI-4P immobilized on nitrocellulose was determined as described previously (12). Briefly, increasing concentrations of PI-4P (0–250 nmol) were spotted on Hi-Bond C membranes, hydrated in blocking buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 3% (w/v) BSA, and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20), and incubated with 50 nm OSBP, OSBP-H524A/H525A and OSBP-R109E/R110E for 1 h at 4 °C. OSBPs were visualized with an 11H9 monoclonal and IRDye-800-conjugated secondary antibody and quantified with an Odyssey Imaging System and application software version 3.0 (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Immunoblotting

Total cell lysates or detergents extracts were solubilized in SDS-PAGE sample buffer (12.5% SDS, 30 mm Tris-HCl, 12.5% glycerol, and 0.01% bromphenol blue, pH 6.8), heated at 90 °C for 5 min, separated on SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose. Proteins were visualized by incubation with primary antibodies followed by IRDye-800 or -680-conjugated secondary antibodies and quantified with an Odyssey Imaging System as described above.

Results

Antibody Detection of Golgi PI-4P Is Inhibited by 25OH and OSBP

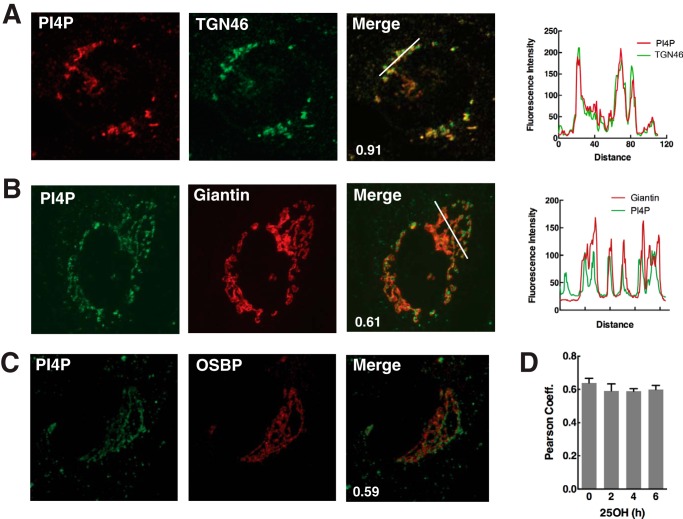

Fluorescent-tagged phosphoinositide-binding proteins and antibodies are increasingly used to probe the distribution and concentration of phosphatidylinositol polyphosphates in cell membranes (29). We employed antibody and transfected headgroup probes to determine whether Golgi PI-4P content was affected by OSBP and 25OH. Initially, PI-4P was visualized in human fibroblasts by immunostaining the Golgi apparatus with a monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1) (24). Confocal imaging of 25OH-treated fibroblasts immunostained for PI-4P revealed prominent co-localization with TGN46 compared with the cis- and medial-Golgi protein giantin (Fig. 1, A and B, and associated line graphs). Endogenous OSBP localizes to the trans-Golgi and TGN (23). However, the correlation coefficient for PI-4P and OSBP in 25OH-treated cells (Fig. 2C) was similar to that for giantin, suggesting that OSBP is shifted toward earlier Golgi compartments or it interferes with PI-4P detection. Co-localization of OSBP and PI-4P (based on Pearson's correlation coefficients) was similar in untreated cells and those treated with 25OH for up to 6 h (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

OSBP partially co-localizes with PI-4P in 25OH-treated cells. Primary fibroblasts were treated with 25OH (6 μm) for 2 h followed by immunostaining for PI-4P and either giantin (A), TGN46 (B), or OSBP (C). A and B, RGB line plots through regions of the Golgi apparatus are shown for selected merged images, and Pearson correlation coefficients are indicated on the merged image. D, Pearson correlation coefficients for OSBP co-localization with PI-4P are shown for fibroblasts treated with 25OH for up to 6 h. Results are the mean and S.D. for 10–16 fields of cells from three independent experiments.

FIGURE 2.

25OH reduces immunodetection of PI-4P in primary fibroblasts. A, human primary fibroblasts were treated with 25OH (6 μm) for 2, 4, and 6 h. No addition (NA) controls received ethanol solvent for 6 h (solvent treatment for 0–6 h did not significantly effect PI-4P detection). Fixed cells were immunostained with primary antibodies against PI-4P and giantin (Golgi), and AlexaFluor-488 and -594 secondary antibodies, respectively. Similarly treated fibroblasts were immunostained for OSBP using AlexaFluor-584 (grayscale images). B, fluorescence intensity of PI-4P immunostaining in the cell (total), cytoplasm, and Golgi apparatus was quantified and expressed relative to the no addition controls. Results are the mean and S.D. of 3–4 experiments. C, immunostaining of PI-4P in the plasma membrane of fibroblasts treated with 25OH.

Although the extent of OSBP and PI4P co-localization in the Golgi apparatus of fibroblasts was unchanged by 25OH treatment, there was a progressive decline in Golgi-associated PI-4P immunostaining that coincided with OSBP localization to the organelle (Fig. 2A). Quantitation of PI-4P fluorescent intensity revealed a 60–70% reduction in Golgi-associated and total PI-4P during a 6-h treatment with 25OH (Fig. 2B). PI-4P in the plasma membrane of fibroblasts, detected using a modified immunostaining technique (24), was not affected by oxysterol treatment (Fig. 2C). PI-4P immunostaining was also quantified in CHO-shNT or CHO-shOSBP cells treated with 25OH for up to 6 h (Fig. 3A). The antibody primarily detected PI-4P in the perinuclear Golgi apparatus of CHO cells (for example see Fig. 9). Similar to results with fibroblasts, 25OH treatment caused a progressive decline in total PI-4P fluorescence in CHO-shNT cells that was significant by 2 h. PI-4P fluorescence intensity in CHO-shOSBP cells was significantly reduced compared with untreated CHO-shNT cells but not further reduced by 25OH treatment. OSBP also associates with the Golgi apparatus when cells are depleted of cholesterol with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (30, 31). Similar to results using 25OH, methyl-β-cyclodextrin treatment of CHO-K1 cells significantly reduced immunodetection of Golgi PI-4P after 2 h (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 9.

Immunostaining of PI-4P in the Golgi apparatus is dependent on the PI-4P binding activity of OSBP. CHO-shOSBP cells were transfected with vectors expressing shRNA-resistant mCherry-tagged OSBP (A), OSBP-HH/AA (B), or OSBP-SBD (C) for 48 h. Cells were subsequently treated with 25OH (6 μm for 2 h) or solvent (NA, no addition) and immunostained for PI-4P. Asterisks in the PI-4P panels indicate cells that are expressing mCherry-OSBPs. Confocal images are 0.5 μm sections. D, quantification of PI-4P fluorescence intensity in non-transfected (NT) and OSBP-expressing cells. Results are the mean and S.D. for 15–20 fields of cells from four independent experiments.

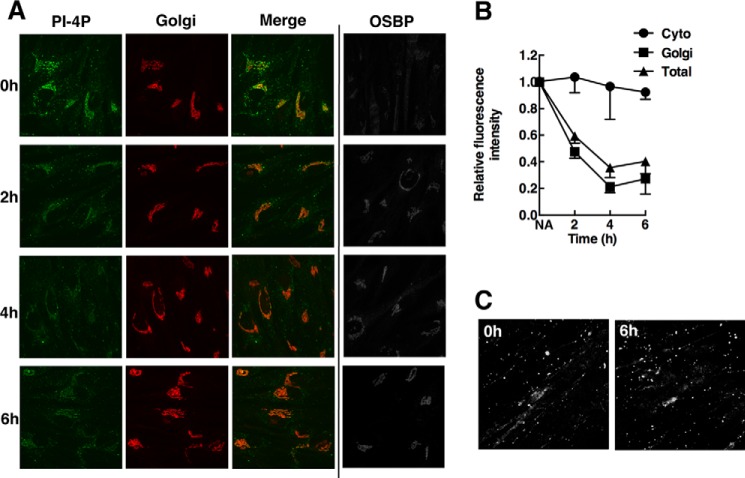

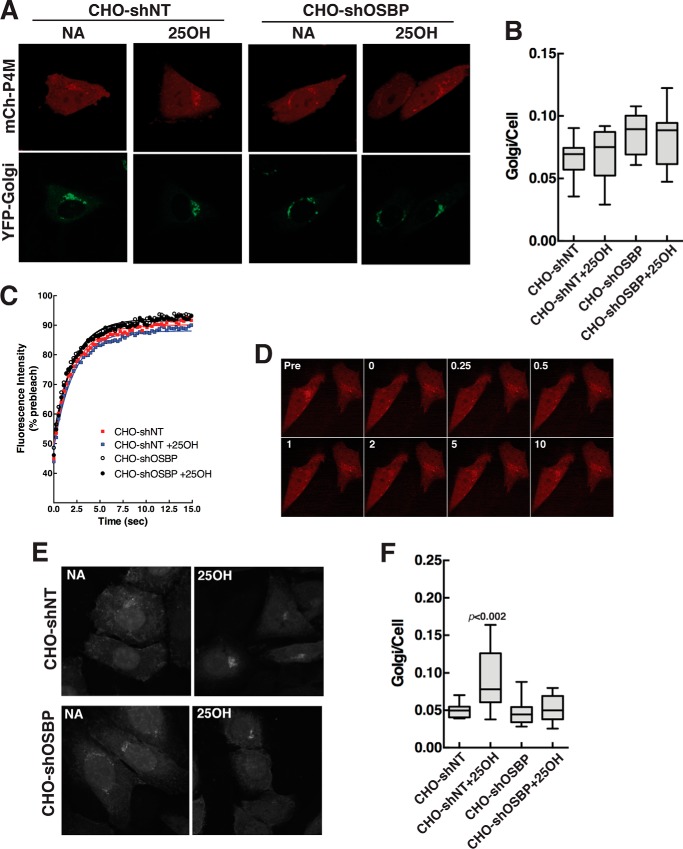

Imaging of PI-4P with antibodies is a potentially biased method that is subject to competition from other PI-4P-binding proteins (24). An alternative approach is to transfect PI-4P-binding modules fused to a fluorescent protein to detect PI-4P in the organelles of live cells. The PI-4P binding domain (P4M) of the Legionella pneumophila SidM protein was recently characterized as an unbiased probe that recognizes the headgroup of PI-4P in the Golgi apparatus, plasma membrane, and endosomes of live cells (26). We transiently expressed mCherry-P4M and a Golgi-specific marker (YFP-Golgi) in CHO-shNT and CHO-shOSBP cells, followed by exposure to 25OH or control solvent. Live cell imaging by spinning disc confocal microscopy revealed that mCherry-P4M was distributed throughout the cell but concentrated in the Golgi apparatus with the YFP-Golgi marker (Fig. 4A). Quantification of fluorescence intensity indicated that Golgi-associated mCherry-P4M was not significantly affected in CHO-shNT or CHO-shOSBP cells after 25OH treatment for 4 h (Fig. 4B). The dynamics of mCherry-P4M association with Golgi PI-4P in OSBP-depleted and oxysterol-treated cells was assessed by FRAP. The recovery of photo-bleached mCherry-P4M (identified by co-localization with YFP-Golgi) over a 15-min time course was also not significantly different between the treatment groups (Fig. 4, C and D). Thus, in contrast to immunostaining results, the presence or absence of OSBP and/or 25OH does not affect the accessibility of Golgi PI-4P to the P4M probe.

FIGURE 4.

Differential detection of PI-4P in the Golgi apparatus by P4M and PH domain probes. A, confocal images of live CHO-shNT and CHO-shOSBP cells transiently co-expressing mCherry-P4M (mCh-P4M) and YFP-Golgi and treated with 25OH (6 μm) or no addition (solvent) for 4 h. B, quantification of the fluorescence intensity of mCherry-P4M in the Golgi apparatus of control and 25OH-treated cells. The box and whisker plots are for 15–25 cells from three experiments (box denotes the interquartile range with a line at the median value, and whiskers indicate the 10th and 90th percentile). C and D, FRAP analysis of Golgi-associated mCherry-P4M was conducted as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A typical photobleach-recovery sequence is shown in C for 25OH-treated CHO-shOSBP cells. The results in D are the means for 16–20 cells from two separate experiments. There was no significant difference between the four experimental groups, and thus error bars were excluded to improve clarity. E, confocal images of fixed CHO-shNT and CHO-shOSBP cells transiently expressing GFP-ORP4-PH and treated as described in A. F, fluorescence intensity analysis of GFP-ORP4-PH in the Golgi apparatus. Box and whisker plots are for 20–40 cells (p values were determined using one-way analysis of variance test). NA, no addition.

PH domains fused to fluorescent proteins are also used to detect PI-4P in cells. However, these probes are often biased or context-dependent, for example detecting PI-4P associated with Arf1 in the case of OSBP and FAPP2 (32). Cells overexpressing OSBP and treated with 25OH displayed increased association of the GFP-OSBP-PH domain with the Golgi apparatus, suggesting expansion of a PH domain-specific pool of PI-4P that is displaced from OSBP by oxysterol (15). We conducted a similar experiment using GFP fused to the ORP4 PH domain, which has conserved PI-4P and Arf1-binding residues found in the structurally related OSBP PH domain (33) and primarily recognizes PI-4P in the Golgi apparatus (27). When transiently expressed and imaged in fixed CHO-shNT cells, GFP-ORP4-PH showed significantly increased association with the Golgi apparatus after 25OH treatment (Fig. 4, E and F). This response was completely blocked in CHO-shOSBP cells, which had levels of Golgi GFP-ORP4-PH similar to untreated CHO-shNT cells. Similar results were obtained when GFP-ORP4-PH was imaged and quantified in live cells (result not shown). Thus, our results with three different probes suggest that OSBP and its oxysterol ligand shift the distribution of PI-4P pools within the Golgi apparatus.

Effect of 25OH and OSBP Depletion on Phosphoinositide Mass

The differential detection of Golgi PI-4P by antibody, PH domain, and P4M probes could be due to changes in PI-4P mass. This was addressed by quantifying the major molecular species PIP and PIP2 by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and multiple reaction monitoring (28). Although this method does not separate monophosphate regioisomers, PI-4P is the most abundant species in mammalian cells, and thus changes in PI-4P should be reflected in total PIP mass (34). In this regard, RNAi depletion of Sac1 in HeLa cells, which should elevate PI-4P levels, resulted in a 20–25% increase in PIP mass (results not shown). In fibroblasts, the abundant PIP-18:0/20:4 species was significantly increased after 4 h of 25OH treatment (Fig. 5A). However, less abundant PIP species and total PIP mass were not significantly affected by 25OH treatment (Fig. 5, A and C). In contrast, PIP2-18:0/20:4 and the less abundant PIP2 molecular species (Fig. 5B), as well as total PIP2 mass (Fig. 5C), were significantly increased by 25OH treatment.

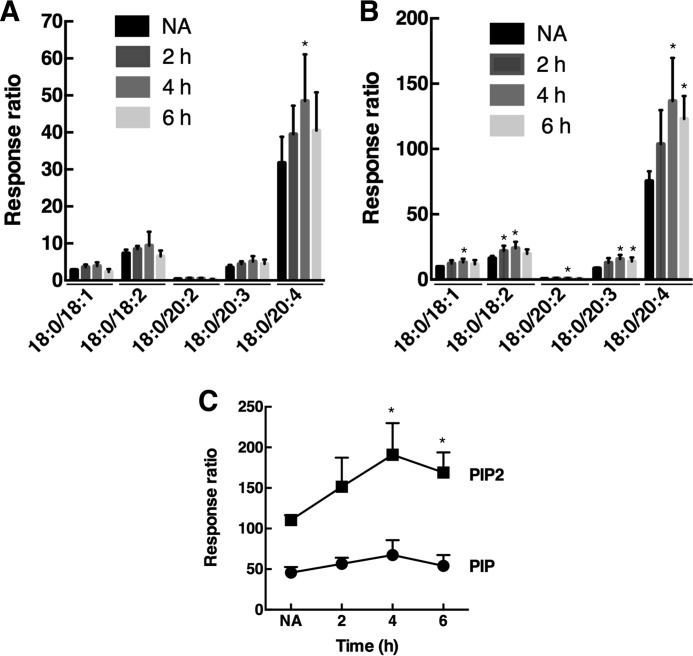

FIGURE 5.

Mass analysis of PIP and PIP2 species in fibroblasts. A and B, mass of individual PIP (A) and PIP2 (B) species was quantified in fibroblasts treated with 25OH for 2, 4, and 6 h or solvent for 6 h (NA, no addition). C, total PIP and PIP mass in 25OH-treated fibroblasts derived from the data in A and B. Results are the mean and S.D. of four experiments (*, p < 0.05 compared with no addition).

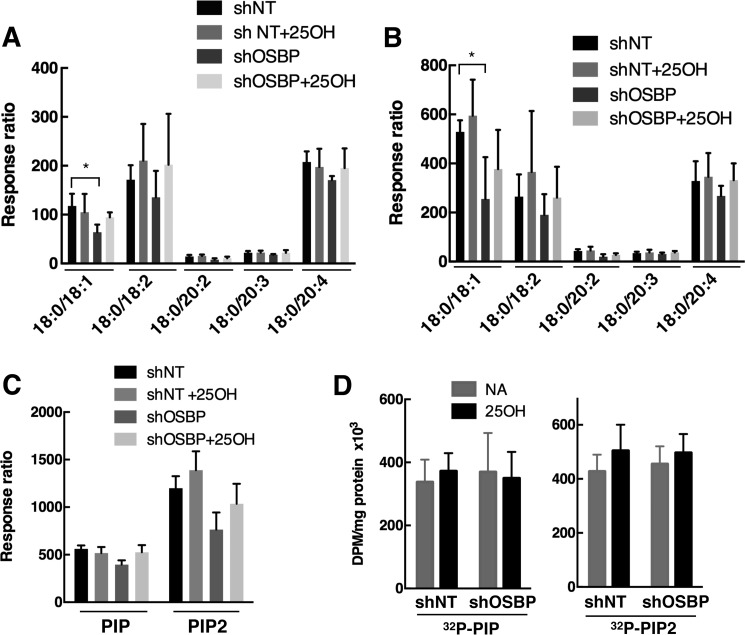

The effect of OSBP depletion and 25OH on PIP mass in CHO cells was also quantified. In CHO-shNT cells, individual PIP molecular species (Fig. 6A) and total PIP mass (Fig. 6C) were not affected by treatment with 25OH. The distribution of PIP molecular species in CHO-shOSBP cells was also unaffected by 25OH. However, PIP-18:0/18:1 was significantly reduced in CHO-shOSBP cells compared with shNT controls (Fig. 6A), and there were minor reductions of other molecular species as well as total PIP mass. The distribution of PIP2 molecular species followed a similar trend, with only minor changes in molecular species and total PIP2 mass (Fig. 6, B and C). PIP and PIP2 mass was also measured indirectly by [32P]phosphate incorporation (Fig. 6D). Under steady-state labeling conditions, there was no difference in the level of radioactive PIP and PIP2 between the treatment groups. Mass analysis suggests that OSBP expression and 25OH have a minimal effect on total cellular PIP levels.

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of PIP and PIP2 mass in CHO cells. A and B, mass of PIP (A) and PIP2 (B) molecular species in CHO-shNT and CHO-shOSBP cells treated with 25OH (6 μm) or solvent control (NA, no addition) for 4 h. Results are the mean and S.D. of 4–5 experiments (*, p < 0.05). C, total PIP and PIP2 mass derived from the data in A and B. D, incorporation of [32P]phosphate into PIP and PIP2 of CHO-shNT or CHO-shOSBP cells treated with 25OH (6 μm) or solvent (NA, no addition) for 6 h. Results are the mean and S.D. of four experiments.

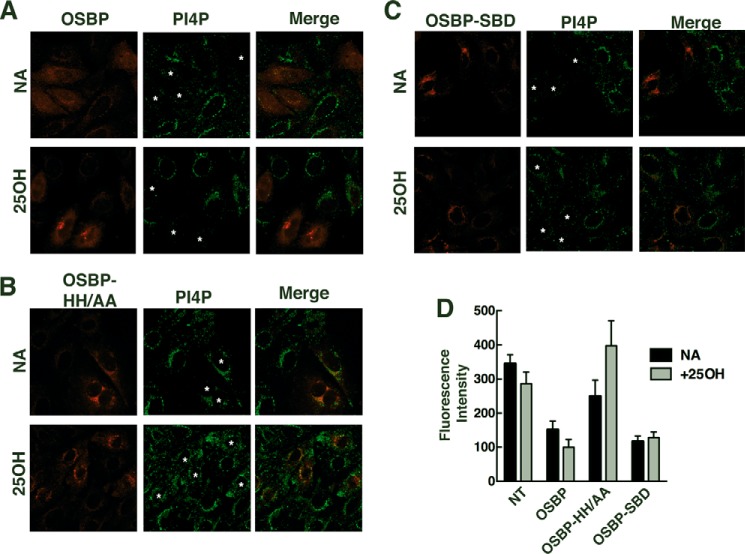

Immunodetection of PI-4P Is Dependent on the PI-4P Binding Activity of OSBP

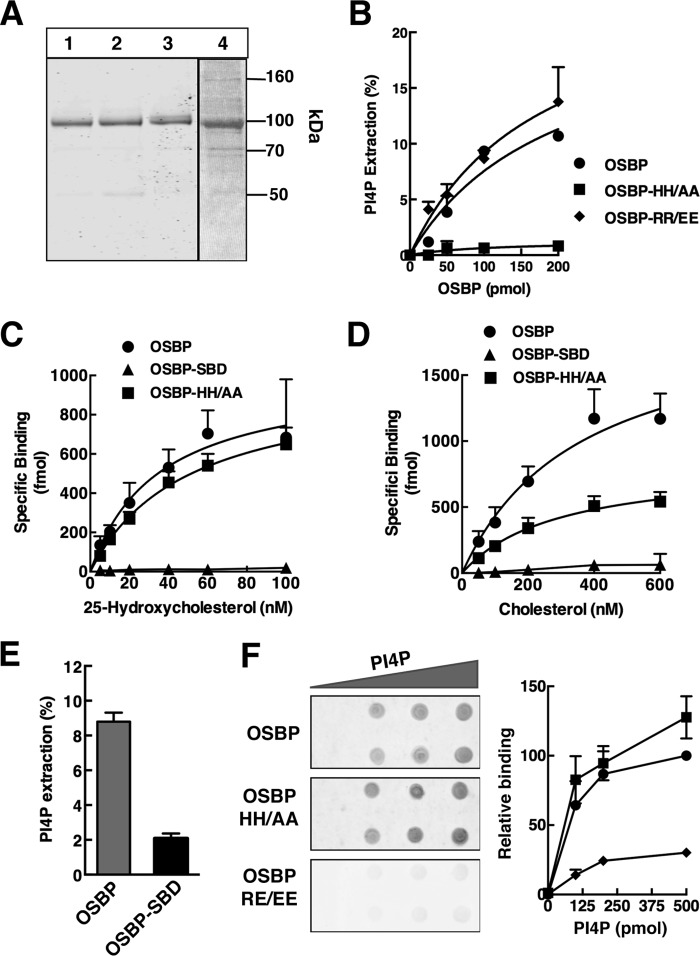

Because cellular PIP mass and Golgi PI-4P (detected with the P4M probe) were unaffected by OSBP expression or 25OH, results with the biased antibody and GFP-ORP4-PH probes appear to indicate a shift in the accessibility of PI-4P at ER-Golgi contact sites. To address this, we determined whether the reduction in Golgi PI-4P immunostaining afforded by 25OH treatment was a function of OSBP expression and its sterol and PI-4P binding activity. These studies required the identification and characterization of OSBP mutants with restricted binding of PI-4P or sterols. Sterol binding-defective OSBP-Δ432–435 (referred to hereafter as OSBP-SBD) (21) and OSBP-H524A/H525A, a PI-4P binding mutant in which two histidine residues that interact with the PI-4P headgroup are mutated to alanine (referred to hereafter as OSBP-HH/AA), were expressed and purified from insect cells by affinity chromatography (Fig. 7A). The purified proteins were assayed for PI-4P and sterol binding activity. As expected, the extraction of [32P]PI-4P from liposomes by OSBP-HH/AA was reduced by >95% compared with OSBP or an OSBP PH domain mutant (R109E/R110E, referred to hereafter as OSBP-RR/EE) (Fig. 7B). The 25OH binding activity of OSBP-HH/AA was similar to wild-type OSBP (Fig. 7C), but maximal cholesterol binding was reduced by 50% (Fig. 7D). OSBP-HH/AA had normal binding to PI-4P that was immobilized on filters, suggesting that its PH domain is functional in vitro (Fig. 7F). Thus, OSBP-HH/AA is a sterol-only binding mutant. The binding of 25OH and cholesterol by OSBP-SBD was almost undetectable (Fig. 7, C and D). [32P]PI-4P extraction by OSBP-SBD was ∼25% of wild-type OSBP activity (Fig. 7), indicating that OSBP-SBD does not bind cholesterol or 25OH but has residual PI-4P binding activity.

FIGURE 7.

In vitro analysis of ligand-restricted mutants of OSBP. A, purified OSBP (lane 1), OSBP-HH/AA (lane 2), OSBP-RR/EE (lane 3), and OSBP-SBD (lane 4) (0.8 μg each) were separated by SDS-8% PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. B, indicated amounts of OSBP, OSBP-HH/AA, or OSBP-RR/EE were incubated with liposomes containing 0.5% [32P]PI-4P, and the extraction of radioactivity into the supernatant was measured. Results are the mean and S.D. of three experiments. C and D, 10 pmol of OSBP, OSBP-HH/AA, or OSBP-SBD (see legend in C) were assayed for specific binding of [3H]cholesterol and 25-[3H]hydroxycholesterol. Results are the mean and S.D. of three experiments. E, extraction of [32P]PI-4P from liposomes by OSBP-SBD (100 pmol). F, binding of 100 pmol of OSBP, OSBP HH/AA, or OSBP-RR/EE (see the legend in B) to PI-4P immobilized on nitrocellulose was quantified after immunoblotting with an anti-OSBP monoclonal antibody. Results are expressed relative to binding of OSBP to 500 pmol of PI-4P and are the mean and S.D. of three experiments.

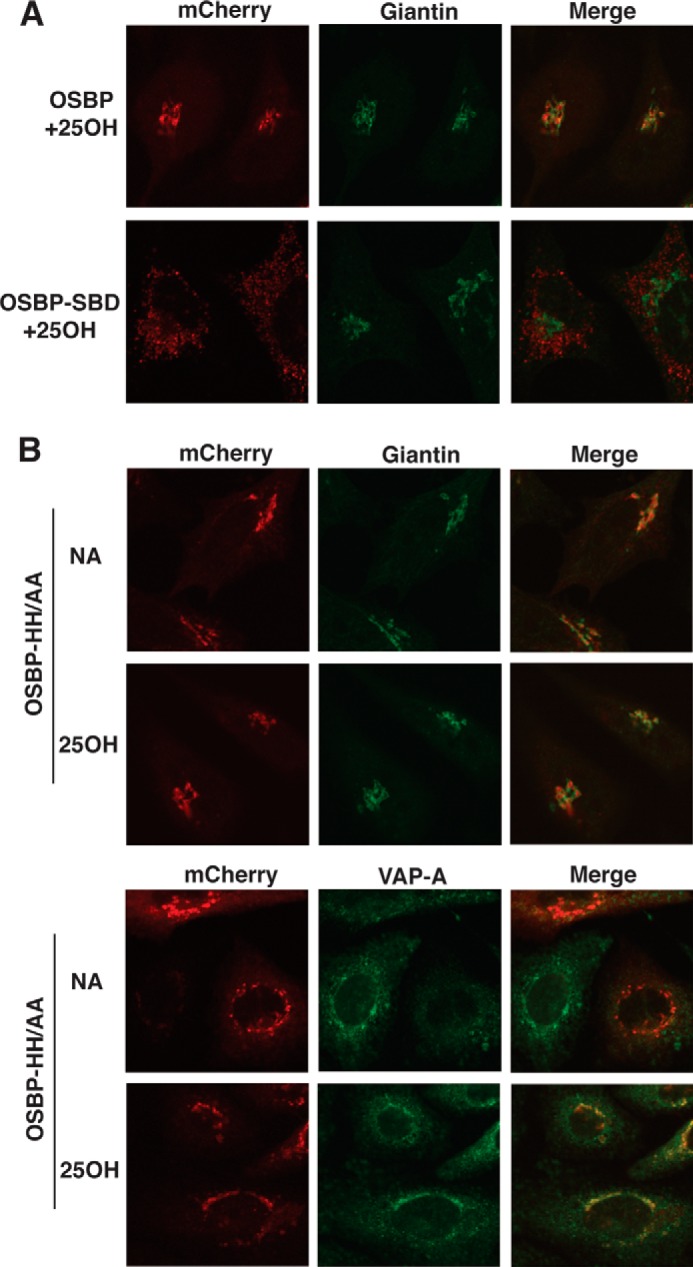

The influence of defective PI-4P and sterol binding on OSBP localization in the ER-Golgi was assessed by transiently expressing mCherry-tagged versions of wild type and mutants in CHO-shOSBP cells and immunostaining for VAPA and the cis-medial Golgi marker giantin. As shown previously (12), mCherry-OSBP is localized with VAPA in the ER of untreated cells but is shifted to the perinuclear Golgi region by 25OH treatment (Fig. 8A). OSBP-SBD co-localized with VAPA in both control and 25OH-treated cells (21). Similarly, mCherry-OSBP-SBD was constitutively localized with VAPA (results not shown, and did not associate with giantin upon exposure of cells to 25OH (Fig. 8A). In untreated CHO-shOSBP cells, mCherry-OSBP-HH/AA was expressed in the Golgi apparatus and did not localize with VAPA (Fig. 8B). After 25OH treatment, mCherry-OSBP-HH/AA remained in the Golgi compartment but also showed substantial co-localization with endogenous VAPA in the perinuclear region. To summarize, the inability to bind sterols results in retention of OSBP-SBD with VAPA in the ER, whereas the PI-4P-binding mutant OSBP-HH/AA was constitutively in the Golgi apparatus but recruited VAPA in the presence of 25OH.

FIGURE 8.

Immunofluorescence localization of PI-4P- and sterol-binding mutants of OSBP. CHO-shOSBP cells were transiently transfected with shRNA-resistant plasmids encoding mCherry-tagged OSBP, OSBP-SBD, and OSBP-HH/AA. A, localization of OSBP and OSBP-SBD with giantin in cells treated with 25OH or solvent (no addition, NA) for 1 h. B, cells transiently expressing OSBP-HH/AA and treated with or without 25OH were immunostained for giantin or VAPA using polyclonal antibodies and AlexaFluor-488-conjugated secondary antibodies. Confocal images are 0.5-μm sections captured using a ×63 objective.

To determine whether the ligand binding activity of OSBP influenced immunostaining of PI-4P, mCherry-OSBP and the ligand-restricted mutants were transiently expressed in CHO-shOSBP cells followed by PI-4P immunostaining. As shown in Fig. 9, A and D, transient expression of OSBP reduced immunodetection of PI-4P compared with non-transfected cells in the same field irrespective of 25OH treatment. Importantly, PI-4P fluorescence intensity in cells expressing OSBP-HH/AA, treated with or without 25OH, was similar to non-transfected cells (Fig. 9, B and D). Control and 25OH-treated cells expressing OSBP-SBD had reduced immunostaining for PI-4P (Fig. 9, C and D). Collectively these data show that immunodetection of Golgi PI-4P is blocked by expression of OSBP that has full or partial PI-4P binding activity and that 25OH is ineffective in displacing PI-4P.

We previously showed that OSBP-SBD was unable to restore 25OH-dependent recruitment of CERT and ceramide delivery to the Golgi apparatus for activation of SM synthesis in CHO-shOSBP cells (21). Similar experiments were performed with OSBP-HH/AA to determine whether this mutant had impaired activity (Fig. 10). CHO-shNT cells displayed a 2.5-fold increase in SM synthesis in response to 25OH treatment (Fig. 10A). Activation of SM synthesis by 25OH was absent in CHO-shOSBP cells but restored by expression of shRNA-resistant pOSBP (Fig. 10, A and D). In cells expressing pOSBP-HH/AA, SM synthesis was increased 1.7-fold in untreated cells but not in the presence of 25OH (Fig. 10A and D). [3H]Serine incorporation into glucosylceramide followed a similar pattern as SM synthesis, but the magnitude of activation by 25OH was less (Fig. 10B). Ceramide synthesis was not affected by OSBP expression or 25OH (Fig. 10C) nor was isotope incorporation into PE or PS (results not shown). The inability of OSBP-HH/AA to restore SM synthesis suggests that PI-4P binding is necessary for 25OH activation of SM synthesis.

Discussion

Mammalian OSBPs and yeast homologues are proposed to use existing PI-4P gradients for the countercurrent transfer of other lipids and sterols between membranes (9, 11, 35). 25OH inhibits the OSBP-mediated exchange of cholesterol and PI-4P between liposomes in vitro, but it activates an alternative pathway for the transport and synthesis of sphingolipids and phosphoinositides in the Golgi apparatus (12, 21–23). This pathway requires PI-4P that could arise by OSBP-dependent mechanisms that involve displacement of PI-4P by oxysterols or by active synthesis or recruitment of PI-4P. The results of our study favor the latter model in which 25OH causes OSBP to actively sequester a pool of PI-4P at Golgi-ER contacts that is available to recruit PH domains.

Headgroup-specific probes have proven indispensable to monitor the location and movement of phosphoinositides in cells. However, competition with endogenous phosphoinositide-binding proteins and context specificity could alter headgroup accessibility and the readout from these probes. This situation arises when measuring PI-4P in the context of OSBP regulation. PI-4P detection in the Golgi apparatus with an antibody was inhibited by OSBP expression and PI-4P binding activity and was evident when endogenous OSBP was activated at the ER-Golgi interface by 25OH. In contrast, 25OH caused increased GFP-ORP4-PH localization to the Golgi apparatus in control CHO-shNT cells but not cells in which OSBP was silenced. These opposing results suggest that the antibody and GFP-ORP4-PH detect Golgi PI-4P in a context-dependent environment. This conclusion is supported by results with the unbiased probe P4M, PIP mass analysis, and radioactive labeling, all of which indicated that Golgi and cellular levels of PI-4P were unaffected by OSBP expression and 25OH. Because PI-4P mass is unaffected, readout from the context-dependent probes suggests that 25OH activation of OSBP converts PI-4P from an antibody-accessible form to one that is detected by the ORP4-PH domain probe. The PI-4P-specific antibody appears to be very sensitive to sequestration of its antigen by other PI-4P-binding proteins. Indeed, we observed that immunodetection was inhibited by the PI-4P binding activity of the OSBP-related protein 9, a family member that functions at the Golgi apparatus (36). However, the ORP4 PH domain detects a pool of PI-4P that is enhanced by oxysterol activation of OSBP, possibly concentrated at the ER-Golgi contacts sites and in close association with Arf1.

The apparent lack of effect of OSBP expression on PI-4P levels contrasts with the role of Osh4p in yeast PI-4p homeostasis (37, 38). Loss of Osh4p function resulted in increased PI-4P mass and probe detection as a result of decreased catabolism by Sac1 at the Golgi apparatus or plasma membrane (35, 38). The lack of effect of OSBP expression on PI-4P mass suggests that its primary function is to regulate PI-4P distribution and not catabolism. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that residual OSBP in shRNA-silenced cells is sufficient to catalyze countercurrent transport and catabolism of PI-4P. In this scenario, PI-4P sequestration at the ER-Golgi contact sites would be more sensitive to the absolute level of OSBP expression.

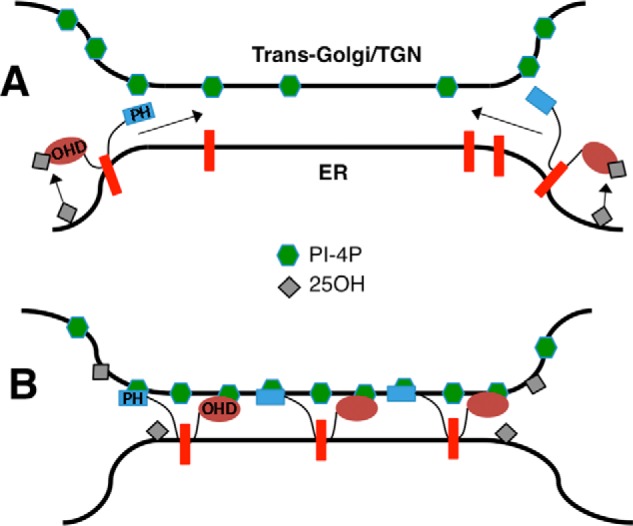

Our results showing that OSBP activation by 25OH leads to increased association of GFP-ORP4-PH with the Golgi apparatus agree with results using an OSBP-PH domain probe (15). However, the interpretation that 25OH is displacing and increasing Golgi PI-4P and interrupting the cholesterol exchange cycle is not consistent with results using other PI-4P probes. Addition of 25OH decreased immunodetection of PI-4P in the absence of any apparent changes in total Golgi PI-4P (based on the P4M probe), arguing against the competitive displacement of PI-4P from the OSBP OHD by 25OH. Instead of increasing Golgi PI-4P by interrupting the OSBP transfer cycle, we propose that OSBP binds 25OH at an ER-Golgi interface where it is exchanged for PI-4P, which remains sequestered in the immediate environment of the membrane contact site (Fig. 11). OSBP at membrane contact sites would increase the local concentration of PI-4P (and perhaps Arf1), generating a membrane platform for recruitment of other transport proteins with structurally related PH domains that recognize PI-4P, such as CERT (39). Recruitment of CERT would increase ceramide transport to the Golgi apparatus for SM synthesis (21, 23).

FIGURE 11.

Redistribution of PI-4P at ER-Golgi contacts by oxysterol activation of OSBP. A, under basal conditions, PI-4P is in a free and unassociated state that is detected by a headgroup-specific antibody. OSBP is cytoplasmic or associated with VAPA (red bar) on the ER. 25OH binding to the OSBP OHD results in localization to ER-Golgi contact sites through PH domain binding to PI-4P. B, OSBP is fully engaged at ER-Golgi contact sites where 25OH is exchanged for PI-4P at the OHD, effectively blocking immunodetection. The PI-4P sequestered at contact sites acts as a recruiting platform for PH domain-containing proteins. OSBP is a dimer but monomers are shown for clarity.

The concept of exchange and sequestration of PI-4P as a requirement for activation of SM synthesis by 25OH is also supported by studies with ligand-restricted mutants of OSBP. OSBP-SBM was constitutively associated with VAPA in the ER, presumably due to its inability to bind sterols. Although this mutant sequestered PI-4P from immunodetection, it did not localize to the ER-Golgi interface and was inactive. The PI-4P-binding mutant OSBP-HH/AA was atypically localized to the Golgi apparatus in untreated cells but was recruited to an ER-Golgi interface in the presence of 25OH. Despite localizing to an ER-Golgi interface, OSBP-HH/AA did not restore SM synthesis in OSBP-depleted CHO cells. The constitutive localization of OSBP-SBM and OSBP-HH/AA in the ER and Golgi, respectively, in the absence of 25OH is consistent with an exchange function that involves cholesterol binding in the ER and PI-4P binding in the Golgi apparatus. The inability of either mutant to activate SM synthesis in the presence of 25OH suggests that OSBP must initially bind 25OH to access the ER-Golgi contact site but then exchange with PI-4P to establish a pool that recruits CERT. An intriguing finding was the partial activation of SM synthesis by OSBP-HH/AA in the absence of 25OH, the opposite result observed for wild-type OSBP. The loss of PI-4P binding to OSBP-HH/AA could enhance its interaction with sterols or another endogenous ligand(s) that promotes the activation of SM synthesis. Based on binding of a variety of natural products and drugs by OSBP (40–42), the endogenous ligands for OSBP could be structurally diverse and not restricted to sterols and phospholipids.

Our results showing the reorganization of Golgi PI-4P pools provide a plausible mechanism for OSBP-mediated recruitment of CERT and stimulation of SM synthesis. The sequestration of PI-4P by OSBP within the ER-Golgi contact site environment would not only recruit other PH domain proteins but also further stabilize the membrane contact.

Author Contributions

A. G. initiated the study, gathered preliminary data, and performed experiments on recombinant OSBPs. M. C. conducted the imaging experiments and mass analysis. N. D. R. conceived the study and wrote the manuscript with input from A. G. and M. C.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Douglas for technical assistance with tissue culture. Alejandro Cohen assisted in the analysis of phosphoinositides by mass spectrometry.

This work was supported by Grant MOP-15284 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the content of this article.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- CERT

- ceramide transfer protein

- FRAP

- fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- 25OH

- 25-hydroxycholesterol

- MRM

- multiple reaction monitoring

- OHD

- OSBP homology domain

- ORP

- OSBP-related protein

- OSBP

- oxysterol-binding protein

- PIP

- phosphatidylinositol monophosphate

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol diphosphate

- PI-4P

- phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- SM

- sphingomyelin

- VAPA

- vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A

- SBD

- sterol binding-defective.

References

- 1.Lagace T. A., and Ridgway N. D. (2013) The role of phospholipids in the biological activity and structure of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 2499–2510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Meer G., Voelker D. R., and Feigenson G. W. (2008) Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 112–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holthuis J. C., and Menon A. K. (2014) Lipid landscapes and pipelines in membrane homeostasis. Nature 510, 48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olkkonen V. M., and Li S. (2013) Oxysterol-binding proteins: sterol and phosphoinositide sensors coordinating transport, signaling and metabolism. Prog. Lipid Res. 52, 529–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alpy F., and Tomasetto C. (2014) START ships lipids across interorganelle space. Biochimie 96, 85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storch J., and Thumser A. E. (2010) Tissue-specific functions in the fatty acid-binding protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32679–32683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngo M., and Ridgway N. D. (2009) Oxysterol binding protein-related protein 9 (ORP9) is a cholesterol transfer protein that regulates Golgi structure and function. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1388–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandutsch A. A., Taylor F. R., and Shown E. P. (1984) Different forms of the oxysterol-binding protein. Binding kinetics and stability. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 12388–12397 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mesmin B., Antonny B., and Drin G. (2013) Insights into the mechanisms of sterol transport between organelles. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70, 3405–3421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suchanek M., Hynynen R., Wohlfahrt G., Lehto M., Johansson M., Saarinen H., Radzikowska A., Thiele C., and Olkkonen V. M. (2007) The mammalian oxysterol-binding protein-related proteins (ORPs) bind 25-hydroxycholesterol in an evolutionarily conserved pocket. Biochem. J. 405, 473–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maeda K., Anand K., Chiapparino A., Kumar A., Poletto M., Kaksonen M., and Gavin A. C. (2013) Interactome map uncovers phosphatidylserine transport by oxysterol-binding proteins. Nature 501, 257–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goto A., Liu X., Robinson C. A., and Ridgway N. D. (2012) Multisite phosphorylation of oxysterol-binding protein regulates sterol binding and activation of sphingomyelin synthesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 3624–3635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong J., Yang H., Yang H., Eom S. H., and Im Y. J. (2013) Structure of Osh3 reveals a conserved mode of phosphoinositide binding in oxysterol-binding proteins. Structure 21, 1203–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Saint-Jean M., Delfosse V., Douguet D., Chicanne G., Payrastre B., Bourguet W., Antonny B., and Drin G. (2011) Osh4p exchanges sterols for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate between lipid bilayers. J. Cell Biol. 195, 965–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesmin B., Bigay J., Moser von Filseck J., Lacas-Gervais S., Drin G., and Antonny B. (2013) A four-step cycle driven by PI(4)P hydrolysis directs sterol/PI(4)P exchange by the ER-Golgi tether OSBP. Cell 155, 830–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser von Filseck J., Čopič A., Delfosse V., Vanni S., Jackson C. L., Bourguet W., and Drin G. (2015) Phosphatidylserine transport by ORP/Osh proteins is driven by phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate. Science 349, 432–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung J., Torta F., Masai K., Lucast L., Czapla H., Tanner L. B., Narayanaswamy P., Wenk M. R., Nakatsu F., and De Camilli P. (2015) PI4P/phosphatidylserine countertransport at ORP5- and ORP8-mediated ER-plasma membrane contacts. Science 349, 428–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagace T. A., Byers D. M., Cook H. W., and Ridgway N. D. (1997) Altered regulation of cholesterol and cholesteryl ester synthesis in Chinese-hamster ovary cells overexpressing the oxysterol-binding protein is dependent on the pleckstrin homology domain. Biochem. J. 326, 205–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyles J. P., McMaster C. R., and Ridgway N. D. (2002) Vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein-A (VAP-A) interacts with the oxysterol-binding protein to modify export from the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29908–29918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loewen C. J., Roy A., and Levine T. P. (2003) A conserved ER targeting motif in three families of lipid-binding proteins and in Opi1p binds VAP. EMBO J. 22, 2025–2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perry R. J., and Ridgway N. D. (2006) Oxysterol-binding protein and vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein are required for sterol-dependent activation of the ceramide transport protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2604–2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peretti D., Dahan N., Shimoni E., Hirschberg K., and Lev S. (2008) Coordinated lipid transfer between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi complex requires the VAP proteins and is essential for Golgi-mediated transport. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3871–3884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banerji S., Ngo M., Lane C. F., Robinson C. A., Minogue S., and Ridgway N. D. (2010) Oxysterol binding protein (OSBP)-dependent activation of sphingomyelin synthesis in the Golgi apparatus requires PtdIns 4-kinase IIα. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 4141–4150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond G. R., Schiavo G., and Irvine R. F. (2009) Immunocytochemical techniques reveal multiple, distinct cellular pools of PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P(2). Biochem. J. 422, 23–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gehrig K., and Ridgway N. D. (2011) CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α (CCTα) and lamins alter nuclear membrane structure without affecting phosphatidylcholine synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1811, 377–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammond G. R., Machner M. P., and Balla T. (2014) A novel probe for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate reveals multiple pools beyond the Golgi. J. Cell Biol. 205, 113–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charman M., Colbourne T. R., Pietrangelo A., Kreplak L., and Ridgway N. D. (2014) Oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP)-related protein 4 (ORP4) is essential for cell proliferation and survival. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 15705–15717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark J., Anderson K. E., Juvin V., Smith T. S., Karpe F., Wakelam M. J., Stephens L. R., and Hawkins P. T. (2011) Quantification of PtdInsP3 molecular species in cells and tissues by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 8, 267–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakelam M. J. (2014) The uses and limitations of the analysis of cellular phosphoinositides by lipidomic and imaging methodologies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841, 1102–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Storey M. K., Byers D. M., Cook H. W., and Ridgway N. D. (1998) Cholesterol regulates oxysterol binding protein (OSBP) phosphorylation and Golgi localization in Chinese hamster ovary cells: correlation with stimulation of sphingomyelin synthesis by 25-hydroxycholesterol. Biochem. J. 336, 247–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridgway N. D., Lagace T. A., Cook H. W., and Byers D. M. (1998) Differential effects of sphingomyelin hydrolysis and cholesterol transport on oxysterol-binding protein phosphorylation and Golgi localization. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31621–31628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godi A., Di Campli A., Konstantakopoulos A., Di Tullio G., Alessi D. R., Kular G. S., Daniele T., Marra P., Lucocq J. M., and De Matteis M. A. (2004) FAPPs control Golgi-to-cell-surface membrane traffic by binding to ARF and PtdIns(4)P. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 393–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry R. J., and Ridgway N. D. (2005) Molecular mechanisms and regulation of ceramide transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1734, 220–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarkes D., and Rameh L. E. (2010) A novel HPLC-based approach makes possible the spatial characterization of cellular PtdIns5P and other phosphoinositides. Biochem. J. 428, 375–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moser von Filseck J., Vanni S., Mesmin B., Antonny B., and Drin G. (2015) A phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate powered exchange mechanism to create a lipid gradient between membranes. Nat. Commun. 6, 6671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu X., and Ridgway N. D. (2014) Characterization of the sterol and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate binding properties of Golgi-associated OSBP-related protein 9 (ORP9). PLoS One 9, e108368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fairn G. D., Curwin A. J., Stefan C. J., and McMaster C. R. (2007) The oxysterol binding protein Kes1p regulates Golgi apparatus phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15352–15357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stefan C. J., Manford A. G., Baird D., Yamada-Hanff J., Mao Y., and Emr S. D. (2011) Osh proteins regulate phosphoinositide metabolism at ER-plasma membrane contact sites. Cell 144, 389–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugiki T., Takeuchi K., Yamaji T., Takano T., Tokunaga Y., Kumagai K., Hanada K., Takahashi H., and Shimada I. (2012) Structural basis for the Golgi association by the pleckstrin homology domain of the ceramide trafficking protein (CERT). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 33706–33718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strating J. R., van der Linden L., Albulescu L., Bigay J., Arita M., Delang L., Leyssen P., van der Schaar H. M., Lanke K. H., Thibaut H. J., Ulferts R., Drin G., Schlinck N., Wubbolts R. W., Sever N., et al. (2015) Itraconazole inhibits enterovirus replication by targeting the oxysterol-binding protein. Cell Rep. 10, 600–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgett A. W., Poulsen T. B., Wangkanont K., Anderson D. R., Kikuchi C., Shimada K., Okubo S., Fortner K. C., Mimaki Y., Kuroda M., Murphy J. P., Schwalb D. J., Petrella E. C., Cornella-Taracido I., Schirle M., et al. (2011) Natural products reveal cancer cell dependence on oxysterol-binding proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 639–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chidley C., Haruki H., Pedersen M. G., Muller E., and Johnsson K. (2011) A yeast-based screen reveals that sulfasalazine inhibits tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]