Abstract

Communication and language barriers isolate Deaf American Sign Language (ASL) users from mass media, healthcare messages, and health care communication, which when coupled with social marginalization, places them at a high risk for inadequate health literacy. Our objectives were to translate, adapt, and develop an accessible health literacy instrument in ASL and to assess the prevalence and correlates of inadequate health literacy among Deaf ASL users and hearing English speakers using a cross-sectional design. A total of 405 participants (166 Deaf and 239 hearing) were enrolled in the study. The Newest Vital Sign was adapted, translated, and developed into an ASL version of the NVS (ASL-NVS). Forty-eight percent of Deaf participants had inadequate health literacy, and Deaf individuals were 6.9 times more likely than hearing participants to have inadequate health literacy. The new ASL-NVS, available on a self-administered computer platform, demonstrated good correlation with reading literacy. The prevalence of Deaf ASL users with inadequate health literacy is substantial, warranting further interventions and research.

Deaf American Sign Language (ASL) users struggle with a variety of communication and language barriers that reduce this group’s opportunities to benefit from mass media, healthcare messages (Barnett, 1999; Tamaskar et al., 2000; Zazove, Niemann, Gorenflo, & Carmack, 1993), and health care communication (McKee, Barnett, Block, & Pearson, 2011; McKee, Schlehofer, et al., 2011). This likely results in a lower general health knowledge (Heuttel & Rothstein, 2001; Peinkofer, 1994; Tamaskar et al., 2000; Wollin & Elder, 2003; Woodroffe, Gorenflo, Meador, & Zazove, 1998; Zazove, 2009), along with existing health disparities (Barnett, 1999; Barnett, Klein, et al., 2011; McKee, Barnett, et al., 2011) in the Deaf population. Deaf ASL users rely on a visual language that does not have a written form. These individuals may lack proficiency in written English (Allen, 1986; Traxler, 2000), which when coupled with social marginalization, places them at potential risk for inadequate health literacy. Health literacy, as defined by the Institute of Medicine, is “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” (Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer, & Kindig, 2004). The lack of a validated and accessible health literacy measure in ASL prevents a reliable assessment of health literacy and the development of potential interventions to address gaps in this particularly high-risk population.

Deaf individuals communicate through a visual language and learn visually. This provides a unique opportunity to determine optimal visual-based information sources to address health literacy gaps for predominately visual learners. For example, low health literacy individuals struggle in locating relevant health information and may have longer fixation duration on irrelevant aspects of displayed online information (Mackert, Champlin, Pasch, & Weiss, 2013). Such a phenomenon could also be particularly important for nearly 20% of Americans who struggle with hearing loss (Agrawal, Platz, & Niparko, 2008; Lin, Niparko, & Ferrucci, 2011; Ries, 1994) and who may be more dependent on visual mechanisms for communication and information access.

Deaf ASL users, like other language minority groups, lack a reliable health literacy instrument (McKee & Paasche-Orlow, 2012). Despite approximately 376 languages being used in the United States, there are very few known health literacy measures available in languages other than Spanish and English (McKee & Paasche-Orlow, 2012). This paper describes the process of adapting, translating, and validating a new computer-based health literacy instrument into ASL and reports the prevalence of inadequate health literacy in Deaf ASL users when compared to their hearing English-speaking peers.

METHODS

Our activities included the selection, translation, and adaptation of a health literacy measurement instrument. Existing health literacy assessment instruments are not suited for Deaf ASL users due to their reliance on pronunciation (e.g., Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine) (Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ), 2014) and reading comprehension (e.g., Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults [TOHFLA]) (Parker, Baker, Williams, & Nurss, 1995). Neither phonetics nor reading of print are aspects of fluency in visual languages. As a starting point in developing a health literacy tool for ASL, we chose to adapt the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) because this instrument is not inexorably linked to phenomena of written languages and could be translated, adapted, and validated into ASL. The NVS assesses health literacy based on a person’s ability to answer 6 questions about a nutrition label and it is an optimal health literacy measurement instrument for the assessing health literacy in health care settings (Vernon, 1983; Weiss et al., 2005). The original NVS was designed to be labeled as inadequate if there were 0–1 correct answers; at risk for limited health literacy (henceforth, called at risk) if there were 2–4 correct answers; and adequate if there were 5–6 correct answers (Weiss et al., 2005). It incorporates aspects of numeracy, document literacy, and reading literacy, while being short enough to use in clinical situations. These different elements of health literacy are critical to accessing health information and making appropriate health-based decisions. For example, numeracy literacy permits the ability to conduct quantitative tasks (i.e., to assess the amount of Tylenol that a child may need) (Golbeck, Ahlers-Schmidt, Paschal, & Dismuke, 2005), while document literacy provides a person’s ability to search, comprehend, and use non-continuous texts in various formats(National Center For Education Statistics, 2003) (i.e., to determine the benefits of immunization from a multimedia handout).

The NVS was originally created and validated in English, then translated and validated in Spanish (Weiss et al., 2005). Compared to the TOFHLA, which served as the gold standard in NVS development, the NVS exhibited a sensitivity of 72% and a specificity of 87% in detecting inadequate health literacy (Weiss et al., 2005). The NVS has been shown to be reliable with relative good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha >0.76 in English and 0.69 in Spanish) (Weiss et al., 2005).

To adapt the NVS into ASL (ASL-NVS), we created a computer interface for administering the ASL-NVS to Deaf individuals (and the NVS to hearing individuals) using the following processes:

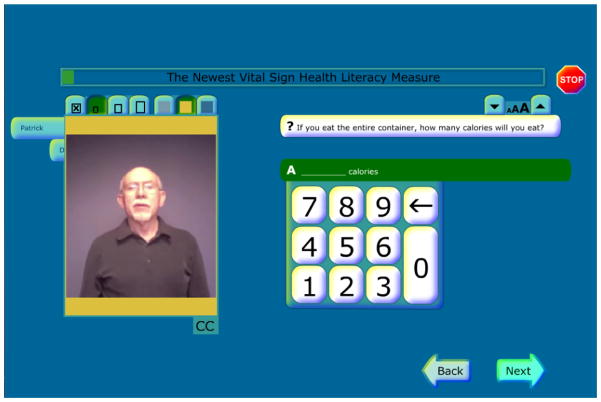

a) translation (and back-translation) of the English text in the original NVS questions (not the actual nutrition label) into ASL through the use of a translation work group (Graybill P, 2010); b) creation of a computer-based survey interface for administration of the questions (see Figure 1); c) in-depth individual cognitive interviews to evaluate the computer interface and the translated survey questions; d) modifications based on feedback received from the interviews; and e) assessment of criterion validity (in the absence of a single gold standard accessible in ASL for this population) of the ASL-NVS instrument when compared to a literacy-related measure, the Peabody Individual Achievement Test-Revised (PIAT-R) reading comprehension subtest (Markwardt, 1989), and educational attainment. The PIAT-R reading comprehension subtest is a nationally standardized test that allows for an efficient individual measure of reading literacy via grade level (Markwardt, 1989). Reading comprehension is assessed in a simple, nonthreatening format that requires only a pointing response for most items (subject chooses one of four pictures that best illustrates a sentence). This multiple-choice format with pictures makes the PIAT-R ideal for assessing low functioning individuals or those with limited literacy abilities level, including individuals with hearing loss. The final ASL-NVS was available also with English captioning (for those who prefer to read) and audio (for hearing individuals) and a signing video along with English captioning support (for Deaf ASL users) on a touch screen computer.

Figure 1.

American Sign Language-Newest Vital Sign Computer Interface

Other Data Collection Measures

We used a modified form of the Deaf Health Survey (DHS) (Barnett, Klein, et al., 2011) from the National Center for Deaf Health Research (NCDHR) to collect demographic information. The DHS, adapted from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey for deaf individuals, was self-administered on a touch-screen computer. Deaf respondents could choose their preferred survey language—ASL or signed English with available English text support. In addition, we assessed basic cardiovascular knowledge held by each participant; we adapted a heart disease fact questionnaire (Wagner’s Heart Disease Fact Questionnaire), (Wagner, Lacey, Chyun, & Abbott, 2005) made up of 25 true/false questions delivered by interviewers, in either English or ASL. The selection of this validated instrument assisted in learning how health literacy adequacy can impact general health knowledge, especially with a language marginalized population with reduced access to health information. There are no known validated general health knowledge instruments at the time of the study so this instrument functioned as a surrogate measure for health knowledge. Cardiovascular health knowledge has been demonstrated to be lower in Deaf populations (Margellos-Anast, Estarziau, & Kaufman, 2006; McKee, Schlehofer, et al., 2011) so it is relevant to assess. The research was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board and the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Covariates

We assessed self-reported demographic covariates: age (continuous); sex (male, female); educational attainment (≤high school, some college, ≥4 year degree), household income (<$25,000, $25,000-<$50,000, ≥$50,000); and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, other). The selection of only two categories for race/ethnicity was due to the lack of diversity in our Deaf ASL user sample. Deaf participants were predominately white (83.95%), similar to demographics of Deaf samples in other published studies (Agrawal et al., 2008; Barnett & Franks, 2002; Schoenborn & Heyman, 2008), suggesting possible hearing loss predisposition among White, non-Hispanic populations.

Sample

We collected data from 405 participants aged 40–70 years over an 18-month period (January 2012–September 2013). Our study sample included 239 hearing English speakers and 166 Deaf ASL users residing in the greater Rochester, New York metropolitan statistical area (MSA). To minimize biases, recruitment approaches were similar for both Deaf and hearing participants. The following recruitment strategies were used: a) health fairs (both Deaf-based and in the general community); flyers at different community locations (e.g. hospitals, bowling alleys, libraries, and laundromats); distribution of study flyers and information through community organizations, including Deaf centers; and several local community health clinics. The majority of the Deaf and hearing participants were recruited by health fairs, community organizations, and community health clinics. The study team, through its screening and consenting process, excluded any potential subjects with developmental delays, cognitive issues, those unable or unwilling to provide written, informed consent, and those who were unable to see and interact with computer-based questionnaires.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses incorporated bivariate and multivariable analyses. Bivariate associations were assessed using chi-square tests for categorical data and Spearman correlations for continuous data. We assessed the correlation between ASL-NVS (or NVS) scores and PIAT-R and the strength of association between ASL-NVS (or NVS) scores and educational attainment. An additional correlation was conducted for ASL-NVS (or NVS) scores and basic cardiovascular knowledge. An ordinal logistic regression model was fit to examine health literacy levels (i.e. inadequate, at risk, and adequate) among Deaf versus hearing as the primary independent variable controlled for sex, age, race/ethnicity, income and education. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.2.

RESULTS

Deaf participants were more likely to be white and non-Hispanic (p<0.01), poorer (p=0.036), have lower scores on the ASL-NVS (p<0.01) and PIAT-R measures (p<0.01) (Table 1). There were no significant differences in other demographic variables between the two groups. The Spearman correlations between the ASL-NVS (or NVS) and the PIAT-R scores were robust for both Deaf (r=0.64; p<0.01) and hearing samples (r=0.67; p<0.01) (Table 2). The strength of associations between the ASL-NVS (or NVS) and the educational attainment were less robust but still significant (Deaf; r=0.49; p <0.01; and hearing; r=0.58; p<0.01) (Table 2). We also conducted an ASL-NVS test-retest analysis to examine reliability during the early data collection period with 7 Deaf participants. These participants were retested after a minimum of one month from their original test. ASL-NVS test-retest reliability based on health literacy categorization (i.e. inadequate, at risk, and adequate) was very robust at 0.84 (Pearson; p=0.02).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Deaf and Hearing Participants

| Hearing Status % (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Variable | All (n = 405) | Deaf (n = 166) | Hearing (n = 239) | p value |

| Age [(mean (SD)] | 54.1 (7.8) | 54.2 (7.9) | 54.0 (7.8) | 0.82 |

| Sex | 0.09 | |||

| Male | 43.0 (174) | 43.4 (72) | 42.7 (102) | |

| Female | 57.0 (231) | 56.6 (94) | 57.3 (137) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.01 | |||

| Other* | 26.4 (106) | 16.1 (26) | 33.5 (80) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 73.6 (295) | 84.0 (136) | 66.5 (159) | |

| Education | 0.11 | |||

| High school or less | 16.1 (65) | 11.5 (19) | 19.3 (46) | |

| Some College | 43.7 (177) | 46.4 (77) | 41.8 (100) | |

| 4-year college or more | 40.3 (163) | 42.2 (70) | 38.9 (93) | |

| Income | 0.036 | |||

| < $25k | 46.0 (177) | 46.8 (72) | 45.5 (105) | |

| $25k – < $50k | 21.8 (84) | 27.3 (42) | 18.2 (42) | |

| $50k+ | 32.2 (124) | 26.0 (40) | 36.4 (84) | |

| Newest Vital Sign | <0.01 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.2) | 2.3 (2.1) | 3.6 (2.2) | |

| Inadequate | 34.8 (140) | 48.5 (79) | 25.5 (61) | |

| At risk | 30.4 (122) | 30.1 (49) | 30.5 (73) | |

| Adequate | 34.8 (140) | 21.5 (35) | 43.9 (105) | |

| PIAT Grade Level | <0.01 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.3 (3.9) | 5.9 (3.2) | 9.8 (3.5) | |

| Less than 8th grade | 47.9 (190) | 74.5 (120) | 29.7 (70) | |

| 8th grade or more | 52.1 (207) | 25.5 (41) | 70.3 (166) | |

| Column percentages reported. | ||||

Other: Included all other races and ethnicity that were grouped together due to smaller n in the Deaf sample. Race/ethnicity breakdown for Deaf and Hearing shown below:

Deaf: Black (n=10; 6.2%), Asian (n=1; 0.6%), Native Indian (n=1; 0.6%), Hispanic ethnicity (n=7; 4.3%) and multi-racial (n=7; 4.3%).

Hearing: Black (n=55; 23%), Asian (n=3; 1.3%), Native Indian (n=4; 1.7%), Hispanic ethnicity (n=13; 5.4%) and multi-racial (n=5; 2%).

Table 2.

Correlations with NVS.

| NVS Categories | ||

|---|---|---|

| Deaf | Hearing | |

|

| ||

| PIAT-R Grade Level | 0.64 | 0.67 |

| <.001 | <.001 | |

| 158 | 236 | |

|

| ||

| Education | 0.49 | 0.58 |

| <.001 | <.001 | |

| 163 | 239 | |

Note. Date shown for each variable are Spearman Correlation Coefficients (top row); Prob > |r| under H0 (Rho = 0) (middle row); and number of observations (bottom row).

In the adjusted analysis controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and income, Deaf participants remained significantly more likely to have inadequate health literacy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 6.88; 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 4.20–11.24) (Table 3). For the heart disease knowledge assessment, Deaf participants had fewer correct answers than hearing individuals [total correct answers 17.5 (SD = 3.6) vs. 21.2 (SD = 2.7); p <0.001]. The overall cardiovascular health knowledge was significantly lower in the Deaf population and the correlation between cardiovascular health knowledge and health literacy scores was higher for the Deaf than for the Hearing (r = 0.21 for Deaf and 0.06 for hearing; p <0.01). The characteristics of the Deaf participants based on adequacy of health literacy were also assessed. Deaf participants with inadequate health literacy were more likely to be older and have lower educational attainment, income, and English reading literacy based on the PIAT-R (Table 4).

Table 3.

Factors that Affect the Probability of Inadequate Health Literacy

| Effect | Point Estimate | 95% Wald Confidence Intervals | p-value Type 3 Analysis of Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.10 | <.001 |

| Gender (Female vs. Male) | 0.94 | 0.61 | 1.45 | 0.789 |

| Other including Multi-racial vs. 2: Non-Hispanic White | 4.07 | 2.34 | 7.08 | <.001 |

| Education 1: HS or less vs. 3: 4-year college or more | 14.58 | 6.66 | 31.92 | <.001 |

| Education 2: Some college vs. 3: 4-year college or more | 4.06 | 2.47 | 6.66 | |

| Income 1: Less than $25k vs. 3: $50k+ | 4.40 | 2.51 | 7.71 | <.001 |

| Income 2: $25k – < $50k vs. 3: $50k+ | 1.63 | 0.89 | 2.97 | |

| Deaf vs. Hearing | 6.88 | 4.20 | 11.24 | <.001 |

Total Sample N=384 (Hearing=231; Deaf 153)

Table 4.

Characteristics of Deaf Participants by Health Literacy Adequacy

| Health Literacy Adequacy % (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Variable | All (n = 163*) | Inadequate (n = 79) | At risk/ Adequate (n =84) | p value |

| Age [(mean (SD)] | 54.1 (7.9) | 56.3 (7.5) | 52.0 (7.7) | <0.01 |

| Sex | 0.78 | |||

| Male | 42.9 (70) | 40.5 (32) | 45.2 (38) | |

| Female | 57.1 (93) | 59.5 (47) | 54.8 (46) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.401 | |||

| Other** | 16.1 (26) | 19.0 (15) | 13.3 (11) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 84.0 (136) | 81.0 (64) | 86.8 (72) | |

| Education | <0.01 | |||

| High school or less | 11.7 (19) | 20.3 (16) | 3.6 (3) | |

| Some College | 45.4 (74) | 59.5 (47) | 32.1 (27) | |

| 4-year college or more | 42.9 (70) | 20.3 (16) | 64.3 (54) | |

| Income | 0.01 | |||

| < $25k | 46.8 (72) | 60.8 (45) | 33.8 (27) | |

| $25k – < $50k | 27.3 (42) | 24.3 (18) | 30.0 (24) | |

| $50k+ | 26.0 (40) | 14.9 (11) | 36.3 (29) | |

| PIAT-R Grade Level | 6.0 (3.2) | 4.1 (2.1) | 7.6 (3.1) | <0.01 |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Less than 8th grade | 74.1 (117) | 94.6 (70) | 56.0 (47) | |

| 8th grade or more | 26.0 (41) | 5.4 (4) | 44.1 (37) | |

| Column percentages reported. | ||||

3 out of 166 Deaf participants either skipped or failed to complete the ASL-NVS assessment (total assessed in table is 163)

Other: includes all other races including Black, Asian, Native Indian, and Polynesian and Hispanic ethnicity. Grouped together due to smaller n.

DISCUSSION

Two findings are notable. First, the ASL-NVS scores demonstrated statistically significant correlations of varying strength with PIAT-R scores, educational attainment, and cardiovascular health knowledge. These data suggest that the ASL-NVS is a useful health literacy instrument for Deaf ASL users. This finding is important because of the absence of any validated tools for assessing health literacy among this population.

Second, this is the first study to our knowledge to assess health literacy among Deaf ASL users. Deaf participants were 6.9 times significantly more likely than hearing participants to have inadequate health literacy. These effects persisted after controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education. A similar finding was observed with the lower reading grade levels as determined by the PIAT-R. The mean reading grade level was 5.9 for Deaf participants and 9.8 for hearing participants. Our findings are consistent with previous studies suggesting that Deaf individuals are at high risk for low reading levels and low health terminology recognition (Allen, 1986; R. Q. Pollard & Barnett, 2009; Traxler, 2000; Zazove et al., 1993).

Lower health literacy in Deaf populations is likely driven by a host of factors. A study evaluating individuals with severe and profound hearing loss from multiple national datasets demonstrated that individuals with hearing loss were significantly more likely to be publicly insured, unemployed, less educated and have lower family incomes (Blanchfield, Feldman, Dunbar, & Gardner, 2001). According to the IOM’s Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion, each of these factors are independently associated with inadequate health literacy (Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2011). An additional contributing factor is information marginalization, which is suggested by worse cardiovascular health knowledge among the Deaf compared to the hearing participants in this study.

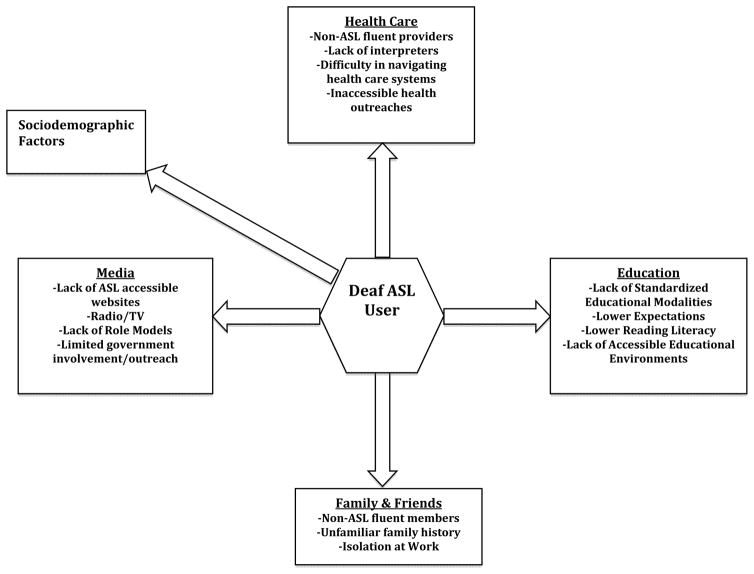

The general population appears to have high levels of family history knowledge of general health issues such as diabetes (Welch, O’Connell, & Schiffman, 2015), but this may not be the case for many Deaf individuals. Since most Deaf individuals have hearing family members, there is frequently a language barrier that results in a loss of family history awareness (Hauser, O’ Hearn, McKee, Steider, & Thew, 2010). The overwhelming majority (95%) of Deaf individuals grow up in a hearing family (Hauser et al., 2010; Mitchell R.E. & Karchmer M.A., 2004). Thus, many have experienced the dinner table syndrome, where they have experienced years at the dinner table watching close family members and friends converse with each other while being unable to decipher what is being said, depriving them of the kinds of incidental learning opportunities that many hearing individuals take for granted (Hauser et al., 2010). This loss of incidental learning opportunities and information marginalization for Deaf individuals occurs on a daily basis regardless from work, schools, friends, families, government, media, and health care situations (see Figure 2 below).

Fig. 2.

Role of incidental learning and marginalization on health literacy.

Many Deaf ASL users learn language, health information, and even culture via peers rather than family (McKee, Schlehofer, et al., 2011)). Language and communication barriers create further obstacles to health literacy for many limited English proficiency populations (Sudore et al., 2009) but appear to be magnified for Deaf individuals. There is often a misunderstanding in both the general hearing community and in the medical establishment that Deaf ASL users are inherently able to understand other communication modalities effectively (e.g., lipreading or writing). These techniques are limited in their scope of effectiveness in relaying information accurately. This highlights the importance of quality health intervention programs that are communicated clearly and succinctly in ASL to address information accessibility. For example, people who are Deaf typically understand less than 30% of what an individual says through lip-reading alone (Commission on Education of the Deaf, 1988; Nicholls, 1982).

Lower literacy levels among Deaf ASL users hinder use of writing communication. The average Deaf ASL users read English at or below a 6th grade level (Allen, 1986; Traxler, 2000; Zazove, Meador, Reed, & Gorenflo, 2013). With poor prose literacy levels and general lack of accessible health information, Deaf individuals struggle with lower “fund of health knowledge” (R. Pollard, 1998) and have reported poor health knowledge in preventive, cardiovascular, cancer, and sexual health (Heuttel & Rothstein, 2001; Margellos-Anast et al., 2006; Peinkofer, 1994; Tamaskar et al., 2000; Wollin & Elder, 2003; Woodroffe et al., 1998).

The robust correlation between the PIAT-R and the ASL-NVS provides further support of the instrument, yet it leads to the question about why reading literacy is relatively poor in the Deaf population in general. Low reading literacy was a characteristic seen among almost all Deaf participants with inadequate literacy. There are likely multiple factors involved. The linguistic aspects of visual ASL dramatically differ from reading English and pose unique literacy challenges. ASL is a developed language with its own unique lexicon and grammatical structures that are quite different from those of English (Klima & Bellugi, 1988). ASL also employs non-manual elements as well, such as body shifts to emphasize changing roles during storytelling or eyebrow movements to distinguish statements from questions. Fortunately, early language development through early intervention programs appear to demonstrate positive educational effects, including reading literacy for Deaf infants and children. (Bat-Chava & Deignan, 2001; Christiansen & Leigh, 2004; Cupples, Ching, Crowe, Day, & Seeto, 2014; Hyde & Punch, 2011; Jimenez, Pino, & Herruzo, 2009; Most, Weisel, & Blitzer, 2007; Priesler, Tvingstedt, & Ahlstrom, 2002). Further research is needed to better tailor the educational system with Deaf children’s needs and backgrounds (Spilt, Koomen, & Harrison, 2015) as a potential way to address both literacy and health literacy disparities. A strong association exists between low education attainment and low health literacy, (Berkman et al., 2004; Gazmararian, Curran, Parker, Bernhardt, & DeBuono, 2005; Kutner, Greenberg, Jin, & Paulsen, 2006), yet this was slightly less robust for the Deaf. This may reflect the loss of incidental learning opportunities despite access to higher learning environments. Health information in ASL is mostly limited. Currently, there is only one known Deaf accessible health website, “DeafHealth.org,” that provides ASL videos on a wide variety of health topics. There are other ASL accessible websites such as the Deaf Wellness Center (University of Rochester Medical Center, 2015) and DeafDoc.org (DeafDOC.org, 2015), but these websites are more limited in regards to the topics they cover. Medline Plus, a health education website hosted by the National Library of Medicine, which includes English information for over 950 diseases, illnesses, health conditions and wellness issues has had only 26 brief medical topics available in sign language. In contrast, there are much larger selections for many other smaller language groups (e.g., 90 health topics in Tagalog), (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2014). Unfortunately, the ASL videos in Medline Plus are no longer available as of January 2015. Furthermore, most health videos (even those on “Deafhealth.org”) are presented in a factual form, not in a dialogic or narrative (story-telling) format that has been shown to be more effective in promoting greater understanding among the Deaf (Austvoll-Dahlgren et al., 2013; Barnett, McKee, Smith, & Pearson, 2011; R. Pollard, 1998).

To improve access to research-based articles and health outreach, novel approaches are taking form. For example, a research journal and a Deaf research library (“ASLized: The Journal of American Sign Language and Literature,” 2015) are promoting the use of digital video-based research articles. These articles, instead of being in a print form, are provided in an ASL format. They are peer reviewed by ASL fluent reviewers, similar to what occurs with the print versions. The dialogic or narrative (story-telling) format is also slowly being incorporated in health outreach to Deaf individuals. The National Center for Deaf Health Research (NCDHR) provided a series of educational videos in ASL in a dialogic format to promote further understanding of a published article. (Barnett, McKee, et al., 2011) Further research is needed to assess the potential impact on information acquisition and health literacy in the Deaf community.

Our findings have several limitations. The use of a literacy measure, i.e., the PIAT-R for criterion validity of the ASL-NVS is limited; however, the lack of a gold standard health literacy instrument necessitated the use of such a test for concurrent validation. We did not compare the ASL-NVS to a numeracy measure. The higher than anticipated educational attainment in our Deaf sample is likely reflective of the Deaf-friendly educational institutions in the Rochester, NY area. This is unlikely to be reflective of the general Deaf population across the United States. This would suggest that the prevalence of inadequate health literacy is likely worse than what we reported in our sample. ASL fluency was also subjectively assessed, limiting the ability to determine if low language fluency was also correlated with inadequate health literacy.

The low racial and ethnicity diversity in the Deaf sample is a limitation and it may reflect potential recruitment bias and possible hearing loss predispositions among White, non-Hispanic populations. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that other factors not accounted for in our model may be confounded our results. The reported findings, however, are novel and represent the first validated health literacy measure in ASL and prevalence of inadequate health literacy in the Deaf ASL population.

Conclusion

The ASL-NVS is a useful health literacy measure for Deaf ASL users. The prevalence of inadequate health literacy among Deaf ASL users is substantial, warranting further research and interventions to address this gap. Additional research is also needed to determine the major drivers of inadequate health literacy in Deaf populations, especially the role of information marginalization, and the focal points at which these drivers can be best addressed. Due to the high proportion of inadequate health literacy among Deaf individuals, health providers and researchers should consider incorporating best practices to address poor health literacy and communication when caring and working with any of these individuals.

Acknowledgments

We are truly grateful to the members of the National Center for Deaf Health Research and the Deaf Health Community Committee for their assistance and input. We especially want to thank Martha Tuttle, Tiffany Panko, Jacqueline Pransky, Matthew Starr, Erika Sutter, Carlene Mowl for their contributions and collaboration throughout the entire research process. Finally, we thank the Deaf community for their ongoing support and participation in our research efforts to learn more about health literacy.

Funding

Dr. McKee is currently supported by grant K01 HL103140 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The project described in this publication used resources that were supported by the University of Rochester CTSA award number UL1 TR000042 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine revised, shorter version (REALM-R) 2014 Retrieved Feb 12, 2015, from http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/pharmhealthlit/realm-r.html.

- Agrawal Y, Platz EA, Niparko JK. Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(14):1522–1530. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen T. Patterns of academic achievement among hearing impaired students. In: Schildroth A, Krachmer M, editors. Deaf Children in America. San Diego: College Hill Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- ASLized. The Journal of American Sign Language and Literature. 2015 Retrieved Feb 6, 2015, from http://aslized.org/jasll/purpose/http://dsdj.gallaudet.edu.

- Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Danielsen S, Opheim E, Bjorndal A, Reinar LM, Flottorp S, Helseth S. Development of a complex intervention to improve health literacy skills. Health Information and Libraries Journal. 2013;30(4):278–293. doi: 10.1111/hir.12037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett S. Clinical and cultural issues in caring for deaf people. Family Medicine. 1999;31(1):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett S, Franks P. Health care utilization and adults who are deaf: relationship with age at onset of deafness. Health Services Research. 2002;37(1):105–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett S, Klein JD, Pollard RQ, Jr, Samar V, Schlehofer D, Starr M, Pearson TA. Community participatory research with deaf sign language users to identify health inequities. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(12):2235–2238. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett S, McKee M, Smith S, Pearson T. Deaf sign language users, health inequities, and public health: opportunity for social justice. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2011;8(2):A45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bat-Chava Y, Deignan E. Peer relationships of children with cochlear implants. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2001;6(3):186–199. doi: 10.1093/deafed/6.3.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, Sheridan SL, Lohr KN, Lux L, Bonito AJ. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 87. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2004. Literacy and health outcomes. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchfield BB, Feldman JJ, Dunbar JL, Gardner EN. The severely to profoundly hearing-impaired population in the United States: prevalence estimates and demographics. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2001;12(4):183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen JB, Leigh IW. Children with cochlear implants: changing parent and deaf community perspectives. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2004;130(5):673–677. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.5.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Education of the Deaf. Toward equality: A report to the President and Congress of the United States. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cupples L, Ching TY, Crowe K, Day J, Seeto M. Predictors of early reading skill in 5-year-old children with hearing loss who use spoken language. Reading Research Quarterly. 2014;49(1):85–104. doi: 10.1002/rrq.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeafDOC.org. Medical Video Dictionary. Health Education for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Community, Interpreters, and Healthcare Professionals. 2015 Retrieved May 3, 2015, from http://deafdoc.org/video-dictionary/medical-video-dictionary/

- Gazmararian JA, Curran JW, Parker RM, Bernhardt JM, DeBuono BA. Public health literacy in America: an ethical imperative. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(3):317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golbeck AL, Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Paschal AM, Dismuke SE. A definition and operational framework for health numeracy. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29(4):375–376. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybill P, Aggas J, Dean R, Demers S, Finnigan E, Pollard R. A community-participatory approach to adapting survey items for deaf individuals and American Sign Language. Field Methods. 2010;22(4):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser P, O’Hearn A, McKee M, Steider A, Thew D. Deaf epistemiology: Deafhood and deafness. American Annals of the Deaf. 2010;154(5):486–492. doi: 10.1353/aad.0.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuttel KL, Rothstein WG. HIV/AIDS knowledge and information sources among deaf and hearing college students. American Annals of the Deaf. 2001;146(3):280–286. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde M, Punch R. The modes of communication used by children with cochlear implants and the role of sign in their lives. American Annals of the Deaf. 2011;155(5):535–549. doi: 10.1353/aad.2011.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Innovations in Health Literacy Research: Workshop Summary. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez MS, Pino MJ, Herruzo J. A comparative study of speech development between deaf children with cochlear implants who have been educated with spoken or spoken+sign language. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2009;73(1):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klima E, Bellugi U. The Signs of Language. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lin FR, Niparko JK, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(20):1851–1852. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.506171/20/1851. pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackert M, Champlin SE, Pasch KE, Weiss BD. Understanding health literacy measurement through eye tracking. Journal of Health Communication. 2013;18(Suppl 1):185–196. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margellos-Anast H, Estarziau M, Kaufman G. Cardiovascular disease knowledge among culturally deaf patients in Chicago. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42(3):235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwardt FC. Peabody Individual Achievement Test-Revised. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- McKee M, Barnett S, Block R, Pearson T. Impact of communication on preventive services among deaf American Sign Language users. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41(1):75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M, Paasche-Orlow M. Health literacy and the disenfranchised: The importance of collaboration between limited English proficiency and health literacy researchers. J Health Comm. 2012;17:7–12. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.712627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M, Schlehofer D, Cuculick J, Starr M, Smith S, Chin NP. Perceptions of cardiovascular health in an underserved community of deaf adults using American Sign Language. Disability Health Journal. 2011;4(3):192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RE, Karchmer MA. Chasing the mythical ten percent: Parental hearing status of deaf and hard of hearing students in the United States. Sign Language Studies. 2004;4(2):138–163. [Google Scholar]

- Most T, Weisel A, Blitzer T. Identity and attitudes toward cochlear implants among deaf and hard of hearing adolescents. Deafness Education International. 2007;9(2):68–82. [Google Scholar]

- National Center For Education Statistics. National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) Three Types of Literacy. 2003 Retrieved May 2, 2015, from https://nces.ed.gov/naal/literacytypes.asp.

- Nicholls G. Cued speech and the reception of spoken language. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1982;25:262–269. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2502.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer A, Kindig D, editors. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1995;10(10):537–541. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinkofer JR. HIV education for the deaf, a vulnerable minority. Public Health Reports. 1994;109(3):390–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard R. Psychopathology. In: Marschark M, editor. Psychological Perspectives on Deafness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 171–197. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard RQ, Barnett S. Health-related vocabulary knowledge among deaf adults. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;54(2):182–185. doi: 10.1037/a0015771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priesler G, Tvingstedt AL, Ahlstrom M. A psychosocial follow-up study of deaf pre-school children using cochlear implants. Child: Care, Health, and Development. 2002;28(5):403–418. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries PW. Prevalence and characteristics of persons with hearing trouble: United States, 1990–91. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 10: Data from the National Health Survey. 1994;(188):1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Heyman K. NCfHS NCHS, editor. NCHS Health EStat. Vol. 2015. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2008. Health disparities among adults with hearing loss: United States, 2000–2006; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Spilt JL, Koomen HM, Harrison LJ. Language development in the early school years: The importance of close relationships with teachers. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51(2):185–196. doi: 10.1037/a0038540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Perez-Stable EJ, Bibbins-Domingo K, Williams BA, Schillinger D. Unraveling the relationship between literacy, language proficiency, and patient-physician communication. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;75(3):398–402. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaskar P, Malia T, Stern C, Gorenflo D, Meador H, Zazove P. Preventive attitudes and beliefs of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9(6):518–525. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.6.518. discussion 526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traxler C. Measuring up to performance standards in reading and mathematics: Achievement of selected Deaf and hard-of-hearing students in the national norming of the 9th Edition Stanford Achievement Test. J Deaf Stud Deaf Edu. 2000;5:337–348. doi: 10.1093/deafed/5.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Health Information in Multiple Languages. MedlinePlus: Trusted Health Information for You. 2014 Retrieved May 5, 2014, from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/languages/languages.html.

- University of Rochester Medical Center. DWC Depression Awareness Ad Campaign. Deaf Wellness Center. 2015 Retrieved May 2, 2015, from https://http://www.urmc.rochester.edu/deaf-wellness-center/scholarship-research/depression-public-service-announcements.cfm.

- Vernon M. Deafness and mental health: Emerging responses. In: Peterson E, editor. Mental health and deafness: Emerging responses. Silver Springs, MD: American Deafness and Rehabilitation Association; 1983. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J, Lacey K, Chyun D, Abbott G. Development of a questionnaire to measure heart disease risk knowledge in people with diabetes: the Heart Disease Fact Questionnaire. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;58(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.07.004. S0738-3991(04)00229-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, Hale FA. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. [Erratum appears in Ann Fam Med. 2006 Jan-Feb;4(1):83] Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(6):514–522. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. Source: NLM. PMC1466931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch BM, O’Connell N, Schiffman JD. 10 years later: Assessing the impact of public health efforts on the collection of family health history. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2015;9999A:1–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollin J, Elder R. Mammograms and pap smears for Australian deaf women. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26(5):405–409. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodroffe T, Gorenflo DW, Meador HE, Zazove P. Knowledge and attitudes about AIDS among deaf and hard of hearing persons. AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):377–386. doi: 10.1080/09540129850124154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazove P. Cancer prevention knowledge of people with profound hearing loss. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(3):320–326. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0895-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazove P, Meador HE, Reed BD, Gorenflo DW. Deaf persons’ English reading levels and associations with epidemiological, educational, and cultural factors. Journal of Health Communication. 2013;18(7):760–772. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.743633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazove P, Niemann L, Gorenflo DW, Carmack C, et al. The health status and health care utilization of the Deaf and hard-of-hearing persons. Archives of Family Medicine. 1993;2(7):745–752. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.7.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]