Abstract

Background

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are typically used as antidepressants. Clinically significant SSRI-induced thyroid dysfunction is rare.

Case

We report a case of hyperthyroidism induced by fluoxetine in a female patient with major depressive disorder. Her thyroid profiles indicated hyperthyroidism after a 10-week treatment with fluoxetine and were restored after discontinuation of fluoxetine and administration with venlafaxine. In the first year of follow-up, her thyroid functions as well as her depressive symptoms remained perfectly normal.

Conclusions

This case highlights the necessity of monitoring thyroid profiles during SSRI treatment.

Key Words: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, fluoxetine, thyroid functions, hyperthyroidism

Thyroid abnormalities can profoundly influence emotional stability and physical activity and are important in the pathogenesis of mental illnesses.1 Thyroid profiles influence the development and differentiation of neuronal and glial cells, which further disturb the cerebral homeostasis and cause changes in neural plasticity, synaptic transmission, and macroscopically, the function of brain.2 The overlap of patients with both thyroid abnormalities and mental illnesses is not a rare issue for clinical endocrinologists and psychiatrists. Moreover, the relationship between hypothyroidism and depression has been generally known, although the intrinsic mechanism remains to be convincingly elucidated.3

Notably, among the numerous factors that can affect thyroid functioning, iatrogenic disturbances in thyroid indices can dramatically affect the course of illness and determine medication treatment strategies.4 We report herein the emergence of thyroid dysfunction during treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for depression in a woman. To our knowledge, this is the first case report to document a reversible, fluoxetine-induced hyperthyroidism after 10-week treatment.

CASE

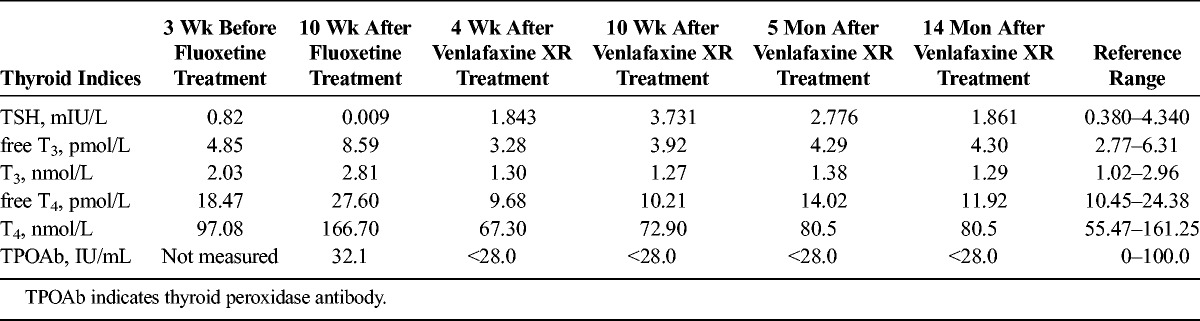

Mrs. A, a 38-year-old Chinese woman, came to the hospital with symptoms of dysphoria, insomnia, poor memory, and headache. She complained that family troubles made her feel depressed, lose all her interests, and intermittently entertain suicidal thoughts. She had no history of systemic diseases or substance abuse, and she denied any family history of psychiatric diseases. Clinical laboratory investigations, including thyroid function tests and a cranial computed tomography scan, were all normal. She was diagnosed with major depressive disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition criteria. She was prescribed 40 mg per day of fluoxetine and 5 mg per day of olanzapine. Three weeks later, her depressive symptoms had significantly improved. To address her remaining depressive symptoms, however, her dosage of fluoxetine was increased to 60 mg per day, and olanzapine was reduced to 2.5 mg per day. Three weeks later, her sleep and appetite had improved, but her affect had become labile. Consequently, fluoxetine was reduced to 40 mg per day. One month later, she complained of palpitation, and her appetite increased. Although laboratory tests for hematological, biochemical, and reproductive systems were all within normal ranges, thyroid function tests revealed significantly elevated total thyroxine (T4), free T4 and free triiodothyronine (T3), relatively low thyrotropin (TSH), and normal level of thyroid peroxidase antibody. To further confirm her condition, a consultation with an endocrinologist was immediately requested and revealed second-degree enlargement of the thyroid, without obvious tenderness on physical examination. Electrocardiogram and chest x-ray results were all normal. A color Doppler ultrasonography scan detected a diffusely enlarged thyroid, but an emission computed tomography scan yielded a normal result. Because her baseline thyroid functioning was normal, no signs of infection were indicated, and she had no exposure to radioactivity or medication (other than the low-dose olanzapine), we diagnosed hyperthyroidism and considered it possibly related to fluoxetine exposure. Immediately, fluoxetine was discontinued, and 150 mg per day of venlafaxine extended release (XR) was initiated, while maintaining the olanzapine dosage at 2.5 mg per day. Four weeks later, her mood had significantly stabilized, and her thyroid hormone levels had generally normalized, with the exception of a slightly low free T4 level, in the absence of any treatment for hyperthyroidism. At follow-up 6 weeks later, her thyroid functions were unchanged, and it became completely normal 5 months after switching to venlafaxine. Her thyroid hormone levels during the whole course are listed in Table 1. Normalization of thyroid function tests after switching from fluoxetine to venlafaxine, despite continuation of the same low dose of olanzapine, indicates that fluoxetine, and not olanzapine, was the inciting agent for Mrs. A's hyperthyroidism.

TABLE 1.

Thyroid Function Levels During Antidepressant Therapy

DISCUSSION

Clinically significant SSRI-induced thyroid dysfunction is rare. To the best of our knowledge, only 4 cases of hypothyroidism associated with SSRI administration—escitalopram-induced subclinical hypothyroidism,5 escitalopram-induced,6 paroxetine-induced7 and sertraline-induced8 hypothyroidism—have been reported previously. Besides, 2 Spanish cases of hyperthyroidism secondary to a long-term treatment of fluoxetine have already been reported in 1999.9 However, limited online information is available for these 2 cases. Our case demonstrates that a short-term usage of fluoxetine may even induce hyperthyroidism in specific individuals. In our case, sufficient hematological and auxiliary examinations have been done to exclude other possibilities which may account for hyperthyroidism. In the first-year follow-up of this patient, thyroid profiles as well as her depressive symptoms remained perfectly normal.

In contrast, clinically silent SSRI-induced abnormalities in thyroid function tests have been widely documented.2,10 After paroxetine treatment in severely depressed patients, for example, T4 level has been reported to decrease by 11.2%. Fluoxetine has been reported to reduce T3 and T4 levels in otherwise euthyroid depressed patients.11 Similarly, sertraline and fluoxetine have been reported to reduce hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone secretion, which would reduce secretion of TSH from the pituitary gland and thyroid hormones from the thyroid.12

As a potent serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitor, fluoxetine can increase the concentration of serotonin in cerebrospinal fluid and other serotonergic tissues. Therefore, serotonin acting at 5-HT2 receptors on the thyroid follicular cells may promote the production and release of thyroid hormones.13 As evident in our depressed patient with hyperthyroidism, we speculate that in susceptible patients, fluoxetine can have a more potent stimulatory effect on the thyroid than inhibitory effects on the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, which ultimately demonstrates as hyperthyroidism.

This case indicates that monitoring of thyroid hormone levels during treatment with SSRIs is warranted, particularly when clinical response is insufficient or otherwise atypical or complicated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the patient for her understanding and permission to publish her case.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bunevicius R. Thyroid disorders in mental patients. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2009; 22 (4): 391– 395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Noda M. Possible role of glial cells in the relationship between thyroid dysfunction and mental disorders. Front Cell Neurosci 2015; 9: 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenspan A, Gharabawi G, Kwentus J. Thyroid dysfunction during treatment with atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66 (10): 1334– 1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dayan CM, Panicker V. Hypothyroidism and depression. Eur Thyroid J 2013; 2 (3): 168– 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mazokopakis EE, Karefilakis CM, Starakis IK. Escitalopram-induced subclinical hypothyroidism. A case report. Hormones (Athens) 2012; 11 (1): 101– 103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eker SS, Akkaya C, Ersoy C, et al. Reversible escitalopram-induced hypothyroidism. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010; 32 (5): 559.e5– 559.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Takahashi M, Sawayama E, Sawayama T, et al. Reversible paroxetine-induced symptomatic hypothyroidism. Pharmacopsychiatry 2007; 40 (5): 201– 202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harel Z, Biro FM, Tedford WL. Effects of long term treatment with sertraline (Zoloft) simulating hypothyroidism in an adolescent. J Adolesc Health 1995; 16 (3): 232– 234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martínez Ortiz JJ. Hyperthyroidism secondary to antidepressive treatment with fluoxetine [article in Spanish]. An Med Interna 1999; 16 (11): 583– 584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. König F, Hauger B, von Hippel C, et al. Effect of paroxetine on thyroid hormone levels in severely depressed patients. Neuropsychobiology 2000; 42 (3): 135– 138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Carvalho GA, Bahls SC, Boeving A, et al. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on thyroid function in depressed patients with primary hypothyroidism or normal thyroid function. Thyroid 2009; 19 (7): 691– 697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackson IM, Luo LG. Antidepressants inhibit the glucocorticoid stimulation of thyrotropin releasing hormone expression in cultured hypothalamic neurons. J Investig Med 1998; 46 (9): 470– 474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tamir H, Hsiung SC, Yu PY, et al. Serotonergic signalling between thyroid cells: protein kinase C and 5-HT2 receptors in the secretion and action of serotonin. Synapse 1992; 12 (2): 155– 168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]