Abstract

Objective

To determine long-term survival for subjects with severe sepsis enrolled in the previous multicenter trial (PROWESS) of drotrecogin alfa (activated) [DrotAA] versus placebo.

Design

Retrospective, cross-sectional, blinded follow-up of subjects enrolled in a previous randomized, controlled trial.

Setting

164 tertiary care institutions in 11 countries.

Interventions

DrotAA (n=850), 24 μg/kg/h for 96 hours, or placebo (n=840).

Participants

The 1690 subjects with severe sepsis enrolled and treated with study drug in PROWESS, of whom 1220 were alive at 28 days (the end of the original PROWESS follow-up).

Measurements and Main Results

Long-term survival data were collected. We had follow-up information on 100% of subjects at 28 days, 98% at hospital discharge, 94% at 3 months, and 93% at 1 year. The longest follow-up was 3.6 years. Hospital survival was higher with DrotAA versus placebo (70.3% vs. 65.1%, p=0.03). There was no statistically significant difference in duration of survival time or in landmark survival rates in subjects who received DrotAA compared with those who received placebo, [median duration of survival = 1113d vs. 846d for DrotAA vs. placebo, p=0.10; landmark survival rates for DrotAA vs. placebo, 66.1% vs. 62.4% at 3 months (p=0.11), 62.2% vs. 60.3% at 6 months (p=0.44), 58.9% vs. 57.2% at 1 year (p=0.49), and 52.6% vs. 49.3% at 2½ years (p=0.21)]. There was a significant interaction (p=0.0008) between treatment assignment and baseline APACHE II scores, suggesting qualitative differences in treatment effect with severity of illness. Subjects with APACHE II ≥25 had better survival time with DrotAA (median duration of survival: 450d vs. 71d, p=0.0005). Survival rates were also higher at landmark timepoints [DrotAA vs. placebo, 58.9% vs. 48.4% at 3 months (p=0.003), 55.2% vs. 45.3% at 6 months (p=0.005), 52.1% vs. 41.3% at 1 year (p=0.002), and 41.7% vs. 32.9% at 2½ years (p=0.001)]. In the APACHE II <25 group there was no significant difference in survival time or survival rates at landmark timepoints except at 1 year (DrotAA vs. placebo, 65.5% vs. 72.0% at 1 year, p=0.04).

Conclusions

The acute survival benefit observed in subjects with severe sepsis who received DrotAA persists to hospital discharge. The survival benefit loses statistical significance thereafter. Post-hoc analysis suggests the effect of DrotAA varies by APACHE II score with improved long-term survival in subjects with APACHE II scores ≥25 but no benefit in those with lower scores.

Keywords: Severe sepsis, mortality, drotrecogin, protein C, recombinant human Activated Protein C, Xigris®, follow-up studies, survival analysis

Severe sepsis is a syndrome characterized by systemic inflammation, coagulopathy, and acute organ dysfunction in response to infection (1). Each year, there are approximately 750,000 cases in the United States, the majority of which are cared for in intensive care units (ICUs) and other intensive care settings (2). Despite current supportive and antimicrobial therapy, short-term mortality remains very high at 30–45% (2–6). Recently, drotrecogin alfa (activated) [DrotAA], a recombinant form of human Activated Protein C with antithrombotic, profibrinolytic, and anti-inflammatory properties (7,8), reduced 28-day all-cause mortality following severe sepsis in a large randomized trial (Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis or PROWESS) (9). This led the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, and many other national regulatory boards to approve DrotAA for the treatment of adults with severe sepsis. Notably, these agencies generally suggested restricting use to sicker patients. For example, the US FDA recommended use in patients with high severity of illness determined, for example, by a high APACHE II (10) score.

There are, however, important limitations to the PROWESS trial (11–14). One key limitation noted by Padkin et al (11) and by Hinds (14) was the lack of follow-up beyond 28 days. Indeed, over 40% of subjects alive at day 28 in PROWESS were still hospitalized (15). Day 28 has been the typical end-point in prior sepsis trials but the few clinical and observational studies with extended follow-up (11,16–21) reported many subjects were hospitalized well beyond 28 days (20) and many subjects died in the following year (18,21) and beyond (17–19,21). These data prompted an international expert panel to suggest follow-up of at least 3–6 months and longer if possible (22). We therefore designed and initiated a cross-sectional observational follow-up study of the subjects enrolled in PROWESS. The study had three aims: to determine the effect of DrotAA on hospital survival; to describe the long-term survival of the two treatment groups over the duration of follow-up, and; to explore the results in select subgroups.

METHODS

Subjects

PROWESS was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of DrotAA [Xigris ®, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN] in subjects with severe sepsis. Entry criteria were reported previously (9). Briefly, after obtaining informed consent, study drug was administered as a 96-hr intravenous infusion at 24 μg/kg/hr to adults presenting with severe sepsis. Subjects at high risk of bleeding and those likely to die from serious conditions other than sepsis within the 28-day follow-up period were excluded from the trial.

PROWESS enrolled and administered study drug to 1690 subjects between July 1998 and June 2000. At 10 centers (which enrolled 14 of 1690 subjects), there were no 28-day survivors. The remaining 154 centers had one or more 28-day survivors potentially eligible for inclusion in the follow-up study. We conducted our follow-up between September 2001 and April 2002, yielding a potential follow-up range of 15 to 45 months.

Study procedures

The original consent for PROWESS did not mention contact beyond day 28. Therefore, this long-term follow-up study was considered a new observational study requiring new ethical review and approval as per specific country and institutional guidelines. Follow-up was conducted by the PROWESS investigator team at each site. Methods included first contacting the subject or family by mail or telephone to obtain written consent. When consent was refused, no information was obtained. When we were unable to locate the subject or her family, if permitted by both national and institutional ethical guidelines, we used information obtained from review of medical records and public vital statistics data. For each subject, the site investigator recorded the last date known to be alive or date of death, and the survival status at hospital discharge if the subject had not been discharged by PROWESS day 28. The subject was recorded as “lost to follow-up” at day 28 if: she refused consent; attempted contact with her was unsuccessful and search of medical and public records was not permissible without consent, or; search was permissible but no information was found. All investigators, subjects, and families remained blinded to treatment assignment during the follow-up period. We ensured data quality through site instruction and supervision regarding follow-up methodologies and through random and non-random data auditing by trained study monitors.

Statistical analyses

The study was designed and conducted after the original PROWESS study had been published. All procedures and primary analyses were specified in advance by investigators at Eli Lilly and Company and at the University of Pittsburgh and provided to the US FDA. We merged the follow-up data with the existing day 1–28 data collected in the original PROWESS cohort (9). Of the 1728 subjects enrolled in PROWESS, the primary analysis was conducted on the 1690 subjects who received either DrotAA or placebo. We conducted our analysis on this cohort.

We compared subject characteristics for those with and without post-day 28 follow-up using Student’s t-tests and Pearson’s chi square tests. We compared hospital survival rates by Pearson’s chi square test. For survival time analyses, we compared treatment group survival curves using the Peto-Wilcoxon test using rho=1 (23). This test disproportionately weights early deaths, which are more likely to be related to the initial episode of severe sepsis. Therefore, this test may be a better measure of how therapy affects deaths that occur early, and are more likely to be due to sepsis. We repeated survival time analyses using the Mantel-Haenszel log-rank test, which treats all deaths equally, regardless of when they occurred. This test gives more insight into how the therapy affects the long-term consequences of severe sepsis. All survival analyses were conducted on all available survival data, censoring subjects beyond last follow-up using traditional Kaplan-Meier methods (24). We present analyses of survival time as survival curves from PROWESS day 1 until the proportion of the overall cohort still alive and in follow-up was approximately 20%, as per recent recommendations by Pocock, et al (25). All events including those not represented in the figures remain in the analyses, consistent with these same recommendations. We also analyzed differences in landmark survival rates at the pre-specified time-points of 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and 2½ years. The Kaplan-Meier estimates for the two treatment groups were compared using a Z-test based on Greenwood’s standard error method (26).

Before unblinding the merged PROWESS and follow-up data, we defined subgroup analyses based on four known predictors of sepsis-associated mortality: age (27,28), functional dependency (29,30), APACHE II score (10), and number of organ dysfunctions (31). The subgroups of age and pre-enrollment functional dependency were prospectively defined for the PROWESS trial and the cut-offs for these subgroups were: age - <60 or ≥60, and functional dependency – pre-enrollment Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale (32) >0 or not. Subgroups by the number of organ dysfunctions (1,2,3,4, or 5) and APACHE II score by quartiles were defined pre-hoc in PROWESS (9). The decision to merge number of organ dysfunctions to single or multiple and the APACHE II score cut-offs in halves was pre-specified prior to unblinding of the long-term follow-up data and was based on the US FDA and European regulatory authorities post-hoc evaluation of the PROWESS data. We tested for treatment by subgroup interaction using Cox models and then repeated the primary analyses specified above on each subgroup.

We conducted survival analyses and treatment group comparisons in SAS (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and S-Plus 2000 Professional Release 3 for PC (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA). We present median duration of survival times in all instances where the median was estimable (i.e., Kaplan-Meier estimated mortality exceeded 50% during the follow-up period). We assumed statistical significance as two-sided p-value <0.05.

RESULTS

Subjects

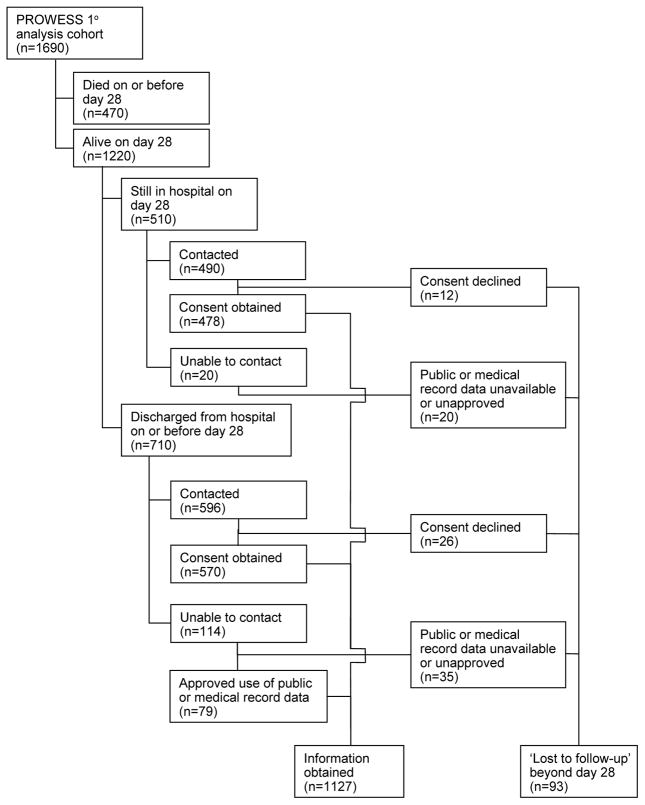

Follow-up is described in Figure 1. Of the 1690 subjects who received either DrotAA or placebo in PROWESS, 1221 were reported alive at day 28 (9). During the follow-up study, we learned that one subject in the DrotAA group originally reported as alive at day 28 in PROWESS had died post-discharge but before day 28. Therefore, there were 1220 day 28 survivors. We established contact with 1086 subjects or families of the 1220 day 28 survivors but 38 declined to participate and follow-up was therefore censored at day 28. We were unable to obtain hospital discharge survival status on 32 subjects (12 subjects declined consent; unable to contact 20 subjects). Missing hospital discharge survival status was primarily the result of the inability of investigators in one country to provide follow-up information based on local regulations. Of the 134 total subjects that we could not contact, we had ethical approval and access to medical and public records for 79 (the remaining 55 were censored at day 28). Thus, we had follow-up data beyond day 28 for 1127 of the 1220 subjects alive at the end of PROWESS. The characteristics of all subjects and those with and without post-day 28 follow-up are presented in Table 1. Subjects lost to follow-up beyond day 28 were significantly younger than those with follow-up. For subjects lost to follow-up, comparisons of baseline characteristics between treatment groups are presented in Table 2. There was no difference in the percentage of subjects lost-to-follow-up by treatment assignment (p=0.48). In subjects lost to follow-up, there were no significant differences in subject characteristics noted between treatment groups.

Figure 1. Subjects.

Flow of PROWESS primary analysis cohort through long-term follow-up study.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

| All N=1690 |

All day 28 survivors with follow-up post day 28 N=1127 |

All day 28 survivors lost to follow-up post day 28 N=93 |

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean ± SD | 60.5±16.8 | 58.6±16.9 | 52.6±17.2 | 0.001 |

| Male, % | 57.0 | 56.9 | 59.1 | 0.67 |

| Caucasian, % | 81.9 | 82.2 | 78.5 | 0.38 |

| Functional independenceb, % | 72.2 | 75.5 | 83.9 | 0.07 |

| Presence of underlying disease | ||||

| Significant underlying disorderc,% | 17.5 | 12.7 | 8.6 | 0.25 |

| APACHE II-CHPd, mean ± SD | 0.97±1.96 | 0.86±1.87 | 0.77±1.96 | 0.69 |

| Disease severity | ||||

| APACHE IIe, mean ± SD | 24.8±7.8 | 23.6±7.3 | 22.6±6.8 | 0.20 |

| APACHE II-APSf, mean ± SD | 20.4±7.1 | 19.6±6.8 | 19.4±6.4 | 0.83 |

| Multiple organ dysfunction at entryg, % | 75.2 | 72.9 | 68.8 | 0.39 |

| Infection type, % | 0.43 | |||

| Gram positive organism only | 25.4 | 25.4 | 25.8 | |

| Gram negative organism only | 22.5 | 23.3 | 18.3 | |

| Mixed gram | 14.8 | 15.8 | 12.9 | |

| Other | 37.2 | 35.5 | 43.0 | |

| Infection site, % | 0.44 | |||

| Lung | 53.6 | 51.8 | 60.2 | |

| Intra-abdominal | 19.9 | 20.0 | 15.1 | |

| Urinary tract | 10.1 | 11.1 | 10.8 | |

| Other | 16.5 | 17.1 | 14.0 | |

DrotAA, drotrecogin alfa (activated); SD, standard deviation.

p-value determined by Student’s t-tests and Pearson’s chi square tests.

Functional dependencies measured by Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale (32) (functional independence=zero dependencies).

Significant underlying disorder (malignancy, neurologic, gastrointestinal, cardiac, pulmonary, status-post-cardiac arrest, profound immunosuppression, or other) as determined by blinded clinical evaluation committee (44).

APACHE II-CHP, Acute Physiology Age and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score chronic health points (10).

Acute Physiology Age and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score (10).

APACHE II-APS, Acute Physiology Age and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score acute physiology points (10).

Organ system dysfunction classified as per Bernard, et al. (9).

Table 2.

Subject characteristics of 28-day survivors lost to follow-up post day 28.

| Placebo n=39 |

DrotAA n=54 |

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean ± SD | 50.4±17.4 | 54.2±17.0 | 0.30 |

| Male, % | 48.7 | 35.2 | 0.19 |

| Caucasian, % | 74.4 | 81.5 | 0.41 |

| Functional independenceb, % | 84.6 | 83.3 | 0.87 |

| Presence of underlying disease | |||

| Significant underlying disorderc,% | 7.7 | 9.3 | 0.79 |

| APACHE II-CHPd, mean ± SD | 0.95±1.95 | 0.65±1.70 | 0.43 |

| Disease severity | |||

| APACHE IIe, mean ± SD | 22.7±7.2 | 22.6±6.6 | 0.94 |

| APACHE II-APSf, mean ± SD | 19.6±7.0 | 19.3±6.0 | 0.85 |

| Multiple organ dysfunction at entryg, % | 61.5 | 74.1 | 0.20 |

| Infection type, % | 0.78 | ||

| Gram positive organism only | 25.4 | 25.4 | |

| Gram negative organism only | 22.5 | 23.3 | |

| Mixed gram | 14.8 | 15.8 | |

| Other | 37.2 | 35.5 | |

| Infection site, % | 0.30 | ||

| Lung | 56.4 | 63.0 | |

| Intra-abdominal | 12.8 | 16.7 | |

| Urinary tract | 17.9 | 5.6 | |

| Other | 12.9 | 14.7 | |

DrotAA, drotrecogin alfa (activated); SD, standard deviation.

p-value determined by Student’s t-tests and Pearson’s chi square tests.

Functional dependencies measured by Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale (32) (functional independence=zero dependencies).

Significant underlying disorder (malignancy, neurologic, gastrointestinal, cardiac, pulmonary, status-post-cardiac arrest, profound immunosuppression, or other) as determined by blinded clinical evaluation committee (44).

APACHE II-CHP, Acute Physiology Age and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score chronic health points (10).

Acute Physiology Age and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score (10).

APACHE II-APS, Acute Physiology Age and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score acute physiology points (10).

Organ system dysfunction classified as per Bernard, et al. (9).

Beginning from PROWESS study day 1, follow-up rates were 100% (n=1690) at 28 days, 98% (n=1658) at hospital discharge, 94% (n=1589) at 3 months, and 93% (n=1575) at one year. The longest follow-up was 3.6 years. After the study database was finalized and analyses were completed, we discovered that appropriate ethical approval was not obtained by one site, affecting two subjects. In compliance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines (33), we reported this incident to the appropriate regulatory bodies and retained the two subjects in the analyses. Sensitivity analyses indicated the inclusion or exclusion of these subjects did not affect study results (data not shown).

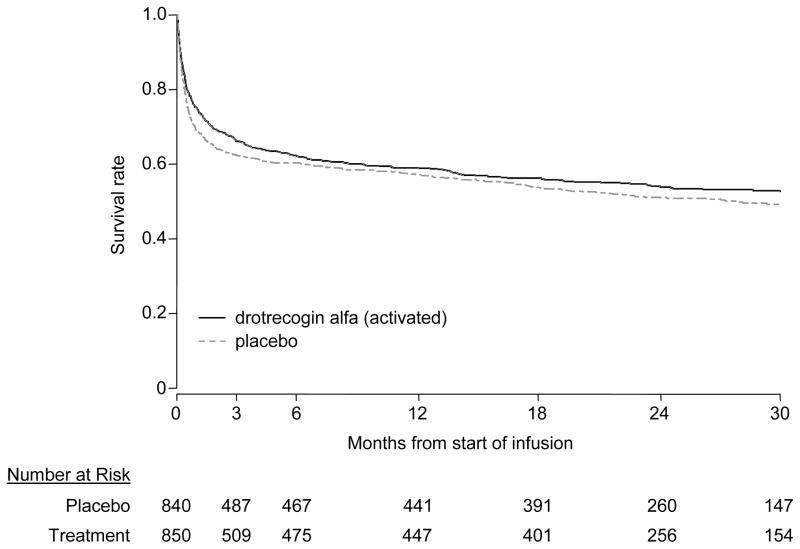

Survival

In the 1658 subjects with known hospital mortality status, the hospital survival rate was significantly higher in subjects receiving DrotAA compared to those receiving placebo (70.3% vs. 65.1%, p=0.03). Survival time-to-event curves by treatment assignment are presented in Figure 2. In both treatment groups, survival continued to deteriorate rapidly beyond day 28, with the rate of decline slowing after 2–3 months. The median duration of survival for the DrotAA subjects was not significantly different (1113 days for DrotAA subjects vs. 846 days for the placebo subjects; p=0.10 by Peto-Wilcoxon and p=0.15 by Mantel-Haenszel). The landmark survival rates and p-values for the DrotAA and placebo groups were 66.1% vs. 62.4% at 3 months (p=0.11), 62.2% vs. 60.3% at 6 months (p=0.44), 58.9% vs. 57.2% at 1 year (p=0.49), and 52.6% vs. 49.3% at 2½ years (p=0.21).

Figure 2. Survival for overall cohort.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves in PROWESS primary analysis population [Peto-Wilcoxon, p=0.10; Mantel-Haenszel, p=0.15 for the comparison of drotrecogin alfa (activated) and placebo survival curves]. The dashed line is placebo and the solid line is drotrecogin alfa (activated). The curves are truncated at 2½ years where the proportion of the overall cohort still alive and in follow-up was 20%, as per recent recommendations (25). The number of subjects at risk are indicated below the x–axis.

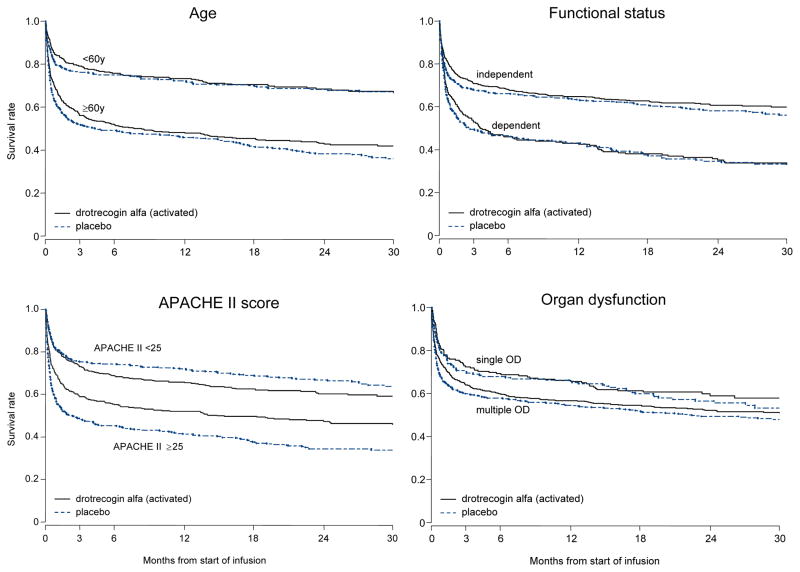

Subgroups

The survival time-to-event curves by treatment assignment for the different subgroups are shown in Figure 3. In general, they resemble those of the overall study population, characterized by a high early mortality and ‘flattening’ of the curves after 3–6 months. The main difference in the curves appears to be the initial mortality rates. The initial slopes of the curves of older subjects, subjects with prior functional dependency, and subjects with greater severity of illness (multiple organ dysfunction or APACHE II ≥ 25) indicate more early deaths than their counterparts - younger subjects, subjects with no functional dependence, and subjects with lower severity of illness. Beyond 3–6 months, the slopes of all the survival curves were flatter and generally similar to each other.

Figure 3. Survival for pre-specified subgroups.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves in PROWESS subgroups of age (<60y, N=741 vs. ≥60y, N=949), functional status [independent, N=1220 vs. dependent, N=470, as measured by pre-enrollment ADL score=0 or not (32)], APACHE II score (<25, N=873 vs. ≥25, N=817), and degree of organ dysfunction (single, N=419 vs. multiple, N=1271). The dashed line is placebo and the solid line is drotrecogin alfa (activated). All four subgroup analyses were pre-specified. There was a statistically significant qualitative difference in treatment effect by baseline APACHE II score evaluated dichotomously (< or ≥25, p=0.0008). There were no significant treatment assignment-by-subgroup interactions for age, functional status, or degree of organ dysfunction subgroups (p values ranging from 0.55–0.91 for all interaction terms introduced into the Cox models).

OD, organ dysfunction.

There was a significant interaction between treatment assignment and the baseline APACHE II score, both evaluating APACHE II dichotomously (< or ≥ 25, p=0.0008) and as a continuous measure (p=0.01). In this post-hoc subgroup analysis, those with APACHE II ≥ 25 treated with DrotAA had better overall duration of survival (median survival time 450d vs. 71d, p=0.0005 by Peto-Wilcoxon and p=0.0004 by Mantel-Haenszel log-rank), and higher landmark survival rates (Figure 3 and Table 3). In subjects with APACHE II <25, the mortality rate did not exceed 50%, therefore a median survival duration was not estimable. There was no difference in duration of survival (p=0.18 by Peto-Wilcoxon and p=0.15 by Mantel-Haenszel log-rank) (Figure 3). There was a significant decrease in landmark survival rate at 1 year for those with low APACHE scores who received DrotAA (p=0.04) but no difference at other time points (Table 3).

Table 3.

Survival rates at landmark time-points by APACHEa II and treatment assignment.

We found no significant treatment assignment-by-subgroup interactions for the age, functional status, or degree of organ dysfunction subgroups (p values ranging from 0.55–0.91 for all interaction terms introduced into the Cox models). The median duration of survival in the DrotAA group compared to the placebo group was 252d vs. 130d for older subjects (p=0.12), 107d vs. 76d for subjects with prior functional dependency (p=0.47), and 936d vs. 681d for subjects with multiple organ dysfunction (p=0.14). Median duration of survival was not estimable for younger subjects, subjects with no prior dependencies, or subjects with single organ dysfunction because mortality did not exceed 50% during follow-up.

DISCUSSION

This is the first long-term follow-up of an agent shown to significantly reduce 28-day mortality following severe sepsis. Survival for both treatment arms continued to fall rapidly over the first few months, consistent with prior findings (18). Subjects treated with DrotAA had higher survival at hospital discharge but there was no statistical difference between treatment arms in duration of survival or differences in survival rates at time points after hospital discharge. Of note, the treatment effect varied significantly with the baseline APACHE score. In post hoc subgroup analysis, there was a large, highly significant survival benefit with therapy in subjects with higher APACHE II scores, but no evidence of benefit in subjects with lower APACHE II scores.

There are important limitations to this study. Although the 28-day PROWESS trial was powered to detect an overall difference in treatment effect, the long-term follow-up study was not. Because we had not obtained prospective consent for long-term follow-up at enrollment into PROWESS, we were encumbered with a number of logistic and ethical issues that would otherwise have never arisen or been simpler to address. Our study was cross-sectional, and therefore subjects were not contacted at regular and comparable time-points. Furthermore, it was only practical to collect information on survival status and we have no data on other important domains such as post-hospital resource use, functional status, quality of life, and satisfaction with care. One advantage of the late decision to initiate follow-up was that we had longer follow-up than would likely have been collected otherwise.

Our analysis plan was specified before conducting the long-term follow-up but we were already aware of the 28-day outcomes. Thus, although we maintained careful blinding procedures throughout the study, there was potential investigator bias in our analysis plan. However, our findings were robust to different analytic approaches. A common problem in follow-up studies is loss to follow-up. However, despite the challenges with the study, we had an excellent follow-up rate. Although we attempted to be restrictive in our subgroup analyses, we computed landmark survival rates at several timepoints. The resulting multiple comparisons increase the chance of a false positive result. In addition, the decision to treat APACHE II scores dichotomously and to compare single organ dysfunction to multiple organ dysfunction was made prior to conducting the long-term follow-up, but after the 28-day results were known. Therefore, these subgroups should be considered post-hoc, with the appropriate caution regarding their interpretation.

The survival rate in the placebo arm is similar to that reported by several other groups, including two single-center cohort studies from North America with one-year follow-up (16,21) and an 8-center study from the US with 6-month follow-up (34). However, the survival is better than that reported for a large Veterans Administration study (18), for a cohort of patients from five US hospitals (17), and for a multicenter British cohort (11). Possible reasons for these differences include differences in the patient populations and differences in the use of co-interventions (11), reflecting the heterogeneity both of severe sepsis and of severe sepsis care (35,36). Thus, the generalizability of our findings likely depends on the extent to which practice mimics that seen in PROWESS with regard to patient selection and management.

To interpret whether the apparent difference in treatment effect by APACHE score might reflect a true difference, we considered the six criteria for interpreting subgroups proposed by Hill (37) and modified by Wedel et al: random chance, biologic gradient, internal consistency, external consistency, confounding, and coherence/plausibility (38). First, it is possible the finding is by random chance. We conducted five treatment-by-subgroup tests of interaction, two of which were of APACHE II, treated as a continuous and as a dichotomous variable. Even by conservative correction for multiple tests, it is likely that the p-value of 0.0008 for treatment by dichotomous APACHE II is significant. However, the possibility of an alpha error persists. Second, the treatment effect was larger in sicker subjects (i.e., subjects with higher APACHE II scores). Thus, the finding is in concert with a biologic gradient.

Third, the finding appears internally consistent: the larger treatment effect with higher APACHE II scores was also seen using the original 28-day end-point; other subgroup analyses stratifying subjects by severity of illness (e.g., degree of organ dysfunction) also found higher observed, though not significant, treatment effects in sicker subjects at 28 days (39) and in long-term follow-up; and non-mortal events, such as cardiovascular or respiratory dysfunction, which were more prevalent in subjects with higher APACHE II scores, resolved more quickly in those subjects receiving study drug (40). Fourth, the finding also appears externally consistent in that it fits with the recent ADDRESS trial of subjects with low APACHE II scores or single organ dysfunction, which was stopped for futility. And, the finding fits with the metaanalysis by Eichacker et al, which suggested that biologic agents targeting the sepsis cascade have larger treatment effects when the placebo groups have higher mortality rates (41).

Fifth, we are unaware of any reason why there would be confounding between APACHE II score and treatment allocation. Finally, it seems plausible that a drug which modulates the sepsis cascade may work better in patients with more severe sepsis. Furthermore, the adverse consequences of side effects such as bleeding may nullify potential gains through mitigation of the sepsis cascade in less sick patients. However, there are insufficient data from other trials by which to assess coherence of findings at this time. Thus, although the finding is post-hoc, and could be by random chance, we believe the decision by the FDA to recommend use of DrotAA in sicker patients, such as those with a high APACHE score, seems sound.

In our previously reported cost-effectiveness analysis (42), we estimated that each additional 28-day survivor would live an additional 12.3 years. Given an improvement in survival of 6.1% at 28 days, this translates into 75.03 additional years per 100 patients treated (0.061 × 12.3 × 100). The point estimate of long-term survival was a median increase of 267 days per treated patient, which is 26,700 days per 100 patients treated or 73.1 years [(267 × 100)/365]. Thus, the follow-up data from this study produces a very similar estimate to that used in our original cost-effectiveness analysis. In the high-risk APACHE II population, we previously reported a cost-effectiveness ratio of $27,400 per QALY and Manns, et al (16) reported a similar cost-effectiveness ratio of $32,872 per QALY. The observation that the absolute reduction in mortality in the APACHE II ≥ 25 population does not diminish much between the 28-day endpoint (13.0% ARR) and the 2.5 year follow-up period (12.0% ARR) supports the idea that published cost-effectiveness estimates in this population are similarly valid.

Choosing one primary end-point to evaluate the efficacy of an anti-sepsis strategy is difficult. Twenty-eight day all-cause mortality and hospital mortality appear to be relevant short-term endpoints. Sepsis is an acute process and its major manifestation, acute organ dysfunction, is strongly associated with short-term mortality. Hence, an agent that modifies the sepsis cascade could mitigate the organ dysfunction and reduce subsequent short-term mortality. However, acute organ dysfunction was not associated with long-term mortality in those who survive the original insult, as shown in the SUPPORT cohort, a heterogeneous cohort of critically ill subjects (29), and in subjects hospitalized with pneumonia (30). Rather, factors such as advancing age and underlying health status appear to be more important (18,28–30), and subjects who develop severe sepsis are frequently elderly and frequently have underlying disease (2).

Given the number of subjects remaining hospitalized beyond 28 days in this and previous reports (20) and the high number of deaths beyond day 28, especially in sicker subjects, the MRC recommendation of combining a short-term primary end-point with long-term follow-up seems prudent. The recent study by Rivers et al of early goal directed therapy also reported outcomes beyond 28 days, finding a significant improvement in mortality at 60 days (43). Whether studies should be powered to find differences in long-term survival remains debatable. In this study, the statistically significant early absolute reduction in mortality at 28 days and hospital discharge diminished over time, suggesting that extremely large sample sizes would be required to detect statistically significant differences long-term for therapies targeting acute illnesses.

In summary, long-term follow-up of a large multicenter sepsis trial is feasible, but sample size may hamper interpretation of long-term survival curves. The treatment benefit with DrotAA noted at 28 days does persist to hospital discharge but is not statistically significant thereafter. The recommendation by the FDA to restrict use of DrotAA to sicker patients, such as those with higher APACHE II scores, is supported by our findings, though we urge caution in the interpretation of this post-hoc analysis as outlined above.

Acknowledgments

Source of support: Eli Lilly and Company

We are indebted to the hard work of all staff who contributed to this study at the 154 institutions around the world. We are also indebted to Barbara Utterback of Eli Lilly and Company for her tireless editorial and administrative support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP ROLES

Dr Angus, a lead investigator for the long-term follow-up study, was involved in all phases of the study and wrote the manuscript. Dr Laterre, a lead investigator for the long-term follow-up study, participated in the design and conduct of the study, provided review and interpretation of the results, and provided critical review of drafts of the manuscript. Dr Helterbrand participated in the design and conduct of the study, performed the statistical analysis, provided interpretation of the results, contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and provided critical review of drafts of the manuscript. Dr Ely participated in the review and interpretation of the results, and provided critical review of drafts of the manuscript. Mr. Ball participated in the design and conduct of the study, provided review and interpretation of the results, contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and provided critical review of drafts of the manuscript. Dr Garg participated in the design and conduct of the study, provided review and interpretation of the results, contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and provided critical review of drafts of the manuscript. Dr Weissfeld participated in the statistical review and interpretation of the results, and provided critical review of drafts of the manuscript. Dr Bernard was the principal investigator of the PROWESS trial that enrolled and treated all of the subjects studied additionally here. Dr Bernard also participated in the review and interpretation of the long-term follow-up results, and provided critical review of drafts of the manuscript.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Drs Angus, Laterre, Ely, and Bernard either currently or previously have received research grant support from Eli Lilly and Company and either currently or previously have provided consulting services to Eli Lilly and Company. Dr Helterbrand is a past employee and stockholder of Eli Lilly and Company. Dr Garg and Mr Ball are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. This study was supported by Eli Lilly and Company.

References

- 1.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padkin A, Goldfrad C, Brady AR, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis occurring in the first 24 hours in the ICU in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Crit Care Med. 2003;9:2332–2338. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000085141.75513.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brun-Buisson C, Doyon F, Carlet J, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults. A multicenter prospective study in intensive care units. French ICU Group for Severe Sepsis. JAMA. 1995;274:968–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies A, Green C, Hutton J, et al. (2001) Severe sepsis: a European estimate of the burden of disease in ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:S284. Abstract 581. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent JL, Bihari DJ, Suter PM, et al. The prevalence of nosocomial infection in intensive care units in Europe. Results of the European Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC) Study. EPIC International Advisory Committee. JAMA. 1995;274:639–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esmon CT. The protein C anticoagulant pathway. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12:135–145. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhainaut JF, Yan SB, Margolis BD, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) (recombinant human activated protein C) reduces host coagulopathy response in patients with severe sepsis. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:642–653. doi: 10.1160/TH02-11-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padkin A, Rowan K, Black N. Using high quality clinical databases to complement the results of randomised controlled trials: the case of recombinant human activated protein C. BMJ. 2001;323:923–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel JP. Assessing the use of activated protein C in the treatment of severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1030–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb021512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren HS, Suffredini AF, Eichacker PQ, et al. Risks and benefits of activated protein C treatment for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1027–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb020574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinds CJ. Treatment of sepsis with activated protein C. BMJ. 2001;323:881–882. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linde-Zwirble WT, Clermont G, Van Hout B, et al. Increased survivorship with drotrecogin alfa (activated) in the treatment of severe sepsis: The effect on hospital costs. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:A1, Abstract 4. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manns BJ, Lee H, Doig CJ, et al. An economic evaluation of activated protein C treatment for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:993–1000. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somogyi-Zalud E, Zhong Z, Lynn J, et al. Dying with acute respiratory failure or multiple organ system failure with sepsis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(Suppl–5) doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quartin AA, Schein RM, Kett DH, et al. Magnitude and duration of the effect of sepsis on survival. Department of Veterans Affairs Systemic Sepsis Cooperative Studies Group. JAMA. 1997;277:1058–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, et al. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA. 1995;273:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brun-Buisson C, Meshaka P, Pinton P, Vallet B EPISEPSIS Study Group. EPISEPSIS: a reappraisal of the epidemiology and outcome of severe sepsis in French intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:580–588. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perl TM, Dvorak L, Hwang T, et al. Long-term survival and function after suspected gram-negative sepsis. JAMA. 1995;274:338–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen J, Guyatt G, Bernard GR, et al. New strategies for clinical trials in patients with sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:880–886. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200104000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrington D, Fleming T. A class of rank test procedures for censored survival data. Biometrika. 1982;69:553–566. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pocock SJ, Clayton TC, Altman DG. Survival plots of time-to-event outcomes in clinical trials: good practice and pitfalls. Lancet. 2002;359:1686–1689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08594-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein JP. Small sample moments of the estimators of the variance of the Kaplan-Meier and Nelson-Aalen estimators. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1991;18:333–340. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moine P, Timsit JF, De Lassence A, et al. Mortality associated with late-onset pneumonia in the intensive care unit: results of a multi-center cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:154–163. doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-1172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quality of Life After Mechanized Ventilation in the Elderly Study Investigators. 2-month mortality and functional status of critically ill adult patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2002;121:549–558. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaagosild P, Dawson NV, Thomas C, et al. Outcomes of acute exacerbation of severe congestive heart failure: quality of life, resource use, and survival. SUPPORT Investigators. The Study to Understand Prognosis and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1081–1089. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clermont G, Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Does acute organ dysfunction predict patient-centered outcomes? Chest. 2002;121:1963–1971. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.6.1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis- Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz S, Akpom CA. A measure of primary sociobiological functions. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6:493–508. doi: 10.2190/UURL-2RYU-WRYD-EY3K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ICH E6: Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guideline. Federal Register. 2 A.D;62:25691–709. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sands KE, Bates DW, Lanken PN, et al. Epidemiology of sepsis syndrome in 8 academic medical centers. Academic Medical Center Consortium Sepsis Project Working Group. JAMA. 1997;278:234–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartman ME, Angus DC. Variation in sepsis care: a wake-up call. Crit Care. 2003;7:211–213. doi: 10.1186/cc2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu DT, Black E, Sands KE, et al. Severe sepsis: variation in resource and therapeutic modality use among academic centers. Crit Care. 2003;7:R24–34. doi: 10.1186/cc2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hill AB. Lancet. 9. London: 1971. Principles on medical statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wedel H, Demets D, Deedwania P, et al. Challenges of subgroup analyses in multinational clinical trials: experiences from the MERIT-HF trial. Am Heart J. 2001;142:502–511. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.117600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ely EW, Laterre PF, Angus DC, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) administration across clinically important subgroups of patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:12–19. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vincent JL, Angus DC, Artigas A, et al. Effects of drotrecogin alfa (activated) on organ dysfunction in the PROWESS trial. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:834–840. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000051515.56179.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eichacker PQ, Parent C, Kalil A, et al. Risk and the efficacy of antiinflammatory agents: retrospective and confirmatory studies of sepsis. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1197–1205. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200204-302OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Clermont G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in the treatment of severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1–11. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dhainaut JF, Laterre PF, LaRosa SP, et al. The Clinical Evaluation Committee in a Large Multicenter Phase 3 Trial of Drotrecogin Alfa (activated) in Patients with Severe Sepsis (PROWESS): Role, Methodology, and Results. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2291–2301. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000085089.88077.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]