Abstract

This study investigated the extent to which parental homework completion during behavioral parent training (BPT) for children with or at risk for developmental delay contributed to parenting and child outcomes. Parents of 48 children (Mage = 44.17 months, SD = 14.29; 73% male; 72% White) with developmental delay (IQ < 75) or at risk for developmental delay (due to premature birth) with co-occurring clinically elevated externalizing behavior problems received Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) as part of two previously completed randomized controlled trials. Parental homework completion was measured using parental report of home practice of treatment skills collected weekly by therapists. Parents also reported on child externalizing behavior problems and levels of parenting stress, while parenting skills were observed during a 5-min child directed play and child compliance was observed during a 5-min cleanup situation. Results indicated that higher rates of parental homework completion predicted parenting outcomes (i.e., increased positive parenting skills and decreased levels of parenting stress) and child outcomes (i.e., lower levels of externalizing behavior problems). Additionally, although limited by temporal precedence, there was an indirect effect of reductions in parenting stress on the negative association between parental homework completion and child externalizing behavior problems. These findings highlight the importance of parents practicing skills learned during BPT for optimizing treatment outcome. Parenting stress was also identified as a potential mechanism by which high levels of parental homework completion contributed to reductions in child externalizing behavior problems.

Keywords: Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, homework, externalizing behavior problems, developmental delay, parenting stress

Externalizing behavior problems, including aggression, defiance, impulsivity, and hyperactivity, have been found to be among the most common difficulties for young children, with prevalence rates ranging from 15% to 30% (Upshur, Wenz-Gross, & Reed, 2009). Externalizing behavior problems are especially common in children with developmental delay and intellectual disability, as they are three to four times more likely to present with clinically significant behavioral problems (Baker, Blacher, Crnic, & Edelbrock, 2002; Dekker, Koot, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2002). In addition to impairments typically associated with developmental delay (e.g., delayed language, difficulties learning), children with co-occurring behavior problems experience a host of additional negative outcomes attributed to behavior problems (Baker et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2003). For example, children with intellectual disability and comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at increased risk for other forms of psychopathology, academic impairment, and deficits in social functioning when compared to children with intellectual disability without ADHD (Pearson et al., 2000). Despite the negative outcomes associated with behavior problems among children with developmental delay, a growing body of research has demonstrated that behavioral parent-training (BPT), an evidence-based treatment for young children with externalizing behavior problems (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008; Pelham & Fabiano, 2008), is effective for children with developmental delay and comorbid behavior problems (Bagner & Eyberg, 2007; McIntyre & Abbeduto, 2008; Roberts, Mazzucchelli, Studman, & Sanders, 2006).

Despite the evident benefits of BPT, parental adherence presents a significant challenge for the attainment and maintenance of treatment gains. In the case of BPT, treatment adherence broadly refers to the enactment of therapist-prescribed behaviors performed by parents within or between sessions in order to produce favorable treatment outcomes (Nock & Ferriter, 2005). Parental homework completion, which refers to parental practice of treatment skills outside of treatment, is often conceptualized as a measure of treatment adherence. BPT programs typically include parental homework assignments that involve regular practicing of specific skills learned in treatment in between sessions (Kazantzis, Deane, Ronan, & L’Abate, 2005). Homework completion has often been used as a proxy for parental adherence to treatment and is positively associated with session attendance (Clarke et al., 2013). However, given previous findings demonstrating that homework completion is a stronger predictor of treatment response compared to session attendance (Clarke et al.; Nix, Bierman, McMahon, 2009), it has also been conceptualized as a measure of quality of parental treatment adherence (Baydar, Reid, & Webster-Stratton, 2003; Nix et al., 2009). Current research on homework completion, however, is limited to prevention efforts for low-income populations and treatments for behavioral problems among typically developing children. To our knowledge, no study has examined the effect of homework completion in parent training on reducing behavior problems in children with developmental delay.

In addition to the lack of research on the effect of homework completion in parent training for children with developmental delay, it is important to consider differences among BPT interventions, such as the extent to which skills are practiced during treatment sessions. Given previous research showing that in-session practice and coaching are beneficial components of BPT (Kaminski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle, 2008), it may be especially valuable to examine the additive effects of homework completion in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), a BPT program for young children with disruptive behavior disorders that incorporates the practice of parenting skills through live coaching during sessions (Eyberg et al., 2008). Only one study to date has examined the role of homework during PCIT and found that in a community sample, families that dropped out of treatment were less likely to complete homework, cancel, or no-show more frequently to sessions, and reported more barriers to treatment participation (Lyon & Budd, 2010). This study, however, did not examine whether homework completion affected child outcomes, parenting skills, or parenting stress, but rather examined homework completion as an outcome.

While previous work suggests homework completion to be an indicator of treatment adherence, active participation in the form of homework completion may also serve as an important mechanism by which BPT interventions reduce child problem behaviors. Indeed, Kling and colleagues (2010) found that within the context of BPT, homework completion mediates changes in conduct problems, such that parents who received an enhanced BPT intervention completed more homework than parents receiving a standard BPT intervention, which resulted in larger decreases in conduct problems (Kling et al., 2010; Tynan, Chew, & Algermissen, 2004). The mediating effect of homework completion may be due to increases in positive and supportive parenting practices (Baydar et al., 2003), which are typically targeted in treatment. Taken together, these findings highlight parents as the agents of change for reducing children’s behavior problems, with active homework completion providing an avenue for parents to hone in on parenting strategies learned in BPT. However, it is unclear as to which mechanisms may explain the effect of homework completion on treatment response.

Despite the aforementioned benefits of parental homework completion, parents from high-risk samples report a host of barriers to homework completion (Chacko, Anderson, Wymbs, & Wymbs, 2013). One key factor that may be associated with barriers to homework completion is parenting stress, which has also been implicated as a predictor of treatment dropout (see Reyno & McGrath, 2006, for a review) and is especially high in parents of children with developmental delay (Baker et al., 2002, 2003). Although numerous studies have shown that BPT interventions are effective at reducing parenting stress (Anastopoulos, Shelton, DuPaul, & Guevremont, 1993; see Chronis, Chacko, Fabiano, Wymbs, & Pelham, 2004, for a review; Pisterman et al., 1992), research is limited in identifying how stress may serve as a potential mechanism by which homework completion affects treatment outcomes.

Previous research has demonstrated links between parental treatment adherence and parenting self-efficacy (Mah & Johnston, 2008), which also has been found to predict parenting stress (Erdwins, Buffardi, Casper, & O’Brien, 2001). It is important to isolate whether reductions in parenting stress are responsible for positive treatment outcomes as a result of increased homework completion. Lastly, given the heightened clinical severity of behavior problems and associated parental stress in children with developmental delay (Baker et al., 2002, 2003), it is particularly important to explore associations between homework completion and parental stress in this population.

CURRENT STUDY

Previous work has shown the benefits of homework completion for improving outcomes during group-based BPT programs (Baydar et al., 2003; Clarke et al., 2013; Kling et al., 2010; Tynan et al., 2004; Villodas et al., 2014). However, no study to date has examined whether homework completion predicts child outcomes and parenting practices in an individual BPT program like PCIT, which naturally has practice time built into the sessions and is associated with a reduction in parenting stress (see Kennedy et al., 2014, for a meta-analytic review). Additionally, we examined this association in a sample of children with or at risk for developmental delay given the heightened levels of behavior problems and parenting stress in this population (Baker et al., 2002, 2003). Furthermore, examining the effects of homework completion in this population may be especially valuable in providing insight into how homework may be particularly beneficial for families with heightened parenting stress and increased clinical severity. Hence, the purpose of this study was to examine the effect of increased homework completion on (a) child behavioral outcomes, (b) parenting skills, and (c) parenting stress. We expected that higher rates of weekly parental homework completion would be associated with reductions in child behavior problems, increases in positive parenting skills, and lower levels of parenting stress. Additionally, we hypothesized that there would be an indirect effect of reductions in parenting stress on the association between parent-reported levels of homework completion on child and parent outcomes.

Method

The current sample consisted of 48 children between the ages of 20 and 70 months (Mage = 44.70 months, SD = 14.27), who had or were at risk for developmental delay and presented with clinically elevated externalizing behavior problems, and their mothers (Mage = 35.11 years, SD = 6.51). Mothers had an ethnic/racial composition of 78% White, 10% Hispanic, 8% Black, and 4% Biracial. Children were mostly boys (73%), with an ethnic/racial composition of 72% White, 12% Hispanic, 8% Black, and 8% Biracial. The average Hollingshead SES score for the sample was in the low- to middle-class range (M = 43.33, SD = 13.98; see Hollingshead, 1975, for a description of the SES four factor index information). The mean IQ for child participants was 71.52 (Mdn = 73.00, SD = 17.33), with 68% of children having IQ scores at or less than 80 and 55% at or below 75. Recruitment for this study consisted of referrals for treatment to an outpatient psychology clinic by pediatric health care professionals (84%), teachers (5%), staff at state-funded early intervention programs (3%), and self-referral (8%). Parent-child dyads in the present study participated in one of two pilot randomized controlled trials in which families were randomly assigned to an immediate treatment (IT) or waitlist control (WL) group. For purposes of this study, we collapsed families across groups and included all families that attended at least one treatment session. As described in more detail below, the “pretreatment assessment” was the assessment immediately preceding the start of treatment (i.e., after a 4-month wait period for families in the waitlist control group), and the “posttreatment” assessment was the assessment conducted 4 months later, which occurred immediately after completion of treatment.

The sample in Study A was comprised of children with developmental delay (IQ score < 75) between the ages of 36 and 70 months. Twenty-two of the 30 families that participated in Study A were included in the current sample. Families that did not participate in a pretreatment assessment (n = 3) or attend at least one treatment session (n = 5) were excluded. Inclusion criteria consisted of: (a) IQ score < 75 on a measure of cognitive functioning and deficits in at least two areas of adaptive functioning as measured by a standard score of 4 or below on the Adaptive Behavior Scale (ABS; Lambert, Nihira, & Leland, 1993) and (b) a diagnosis of oppositional-defiant disorder (ODD) based on Jensen et al. (1996) criteria for optimal caseness, which included a rating above the borderline clinically significant range (i.e., T score > 64) on the Aggressive Behavior subscale on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) and a diagnosis of ODD on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children–Fourth Edition–Parent Version (DISC-IV-P; Shaffer et al., 2000). All of the children in Study A were diagnosed with either mild or moderate mental retardation according to DSM-IV-TR criteria (now intellectual disability according to DSM-5). Additionally, the primary caregiver was required to receive a standard score of 75 or above on the Wonderlic Personnel Test (Dodrill, 1981), a parent-completed cognitive screening measure, to ensure the parents’ ability to learn the skills in PCIT. Exclusion criteria included evidence of any major sensory impairment (e.g., deafness, blindness), autism spectrum disorder, and child significant motor impairments (e.g., cerebral palsy). See Bagner and Eyberg (2007) for a full sample description.

In Study B, the sample was comprised of children who were born premature (i.e., < 37 weeks gestation) and therefore were at risk for a developmental delay and were between the ages of 20 and 60 months. Twenty-six of the 28 families that participated in Study B were included in the current sample. As in Sample A, families that did not participate in a pre-treatment assessment or attend at least one treatment session (n = 2) were excluded. Some children did not have an IQ score below 80, yet were still included in the analyses due to the future risk for developmental delay (Censullo, 1994). In addition to premature birth status, inclusion criteria were similar to Study A and consisted of a score above the borderline clinically significant range (i.e., T score > 60) on the Externalizing Behavior scale on the CBCL, as well as a standard score at or above 75 on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler, 1999) for mothers. Although no measures of adaptive functioning necessary for a diagnosis of mental retardation were collected in Study B, 25% of children had IQs below 75. Exclusion criteria included evidence of a major sensory impairment (e.g., deafness, blindness), autism spectrum disorder, or child significant motor impairment (e.g., cerebral palsy). See Bagner, Sheinkopf, Vohr, and Lester (2010) for a full sample description.

Inclusionary criteria differed in the two samples as a function of age. Children in Study A were between the ages of 3 and 6 years, thus Jensen et al.’s (1996) criteria for diagnosing ODD was utilized. Some of the children in Study B were younger than 3 years, so no diagnostic system was utilized and instead externalizing behavior problem cutoff scores were deemed more appropriate. Although specific inclusionary criteria with regard to child behavior problems were different for Study A and Study B, all children included in Study A (all had CBCL aggression T-score > 64) also met child behavior criteria for Study B (all had CBCL externalizing T-scores > 60). Additionally, children from Study A and B did not differ on their baseline levels of externalizing behavior problems or aggressive behavior as measured by the CBCL: F (1, 43) = 2.59, p = .12; F (1, 43) = 1.85, p = .18, respectively. There were no baseline differences on demographic characteristics or outcome measures between participants in Study A and Study B. However, children in Study A tended to be older, F (1, 45) = 16.54, p < .001, and had lower IQs, F (1, 45) = 51.75, p < .001, than children in Study B. Therefore, all subsequent analyses controlled for child age and IQ. There were also no baseline differences on demographic characteristics or outcome measures between families in the IT and WL among this entire sample.

MEASURES

Child Cognition Screener

For children younger than 3 years of age in Study B, the Bayley Scales for Infant and Toddler Development–Third Edition (Bayley, 2006) was administered to assess cognitive ability for descriptive purposes. Children 3 years and older in both studies were administered the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Third Edition (WPPSI-III; Wechsler, 2002) to assess cognitive functioning. Both tools have been widely used and are reliable (Wechsler, 2002). Inclusion criteria for Study A required the child to have a developmental delay (IQ score < 75) on the full scale of the WPPSI-III.

Maternal Cognition Screener

To ensure parents’ ability to learn skills in PCIT, mothers were administered The Wonderlic Personnel Test (Dodrill, 1981) in Study A and the WASI (Wechsler, 1999) in Study B, both of which are reliable measures of adult cognition (Dodrill, 1983; Wechsler, 1999) and were required to score > 75 on these measures.

Parent Rating of Child Disruptive Behavior

Parents completed the CBCL (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) for 1 ½ to 5 year olds. The CBCL is a 99-item parent rating scale to assess the frequency of child behavioral and emotional problems. The CBCL has excellent test-retest and interrater reliability as well as concurrent and discriminant validity (Achenbach & Rescorla). Children with a rating above the borderline clinically significant range (i.e., T-score > 64 on the Aggressive Behavior subscale in Study A and T-score > 60 on the externalizing behavior scale in Study B) were included in the current study. The externalizing problems total scale was utilized as a measure of child treatment outcome. In this sample, internal consistency estimates were .70 for the aggressive behavior subscale and .83 for the externalizing behavior scale.

Parent Rating of Parenting Stress

The Parenting Stress Index–Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, 1995) is a parent self-report measure of parenting stress containing 36 items and comprised of three scales (Parental Distress, Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction, and Difficult Child) and a total score with high 6-month test-retest reliability coefficients (Abidin, 1995). Studies examining the psychometric properties of the PSI-SF are often unable to replicate the original 3-factor structure (Haskett, Ahern, Ward, & Allaire, 2006; Reitman, Currier, & Stickle, 2002). Additionally, factors representative of parental distress are highly correlated with factors of child-rearing distress and total stress scales (Haskett et al., 2006). Thus, for the purposes of this study and to reduce the number of analyses (and thus Type I error), we utilized the total stress score (internal consistency estimate of .92).

Behavior Coding System

The Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS; Eyberg, Nelson, Duke, & Boggs, 2004) is a behavioral coding system that measures the quality of parent-child interactions. Support for the reliability and validity of the DPICS has been reported (Eyberg et al., 2004). For this study, we chose the coding categories that were most relevant to treatment outcome. Specifically, we created two composite categories to reflect the skills parents learn in PCIT: “do skills,” which included behavior descriptions, reflections, and praises, and “don’t skills,” which included questions, commands, and negative talk. Do and don’t skills were assessed during a 5-min observation of child-directed play, where the mother was instructed to follow her child’s lead in play. Child alpha compliance was also coded during a 5-min clean-up situation and was defined as the number of times the child complied to a parent command (providing the child with an opportunity to comply) divided by the total number of commands (providing the child with an opportunity to comply). Coding was completed by undergraduate students who were blind to group status and were trained to 80% agreement with a criterion tape. Observations (50%, N = 28) were coded a second time for reliability and percent agreement ranged from 58% to 91% for individual codes, and kappa estimates ranged from .41 to .89 for individual codes (guidelines specify that values above .40 indicate fair agreement; Landis & Koch, 1997). It is important to note that some “don’t” skills, particularly questions and commands, may not necessarily constitute “negative” practices outside the context of play.

Parental Homework Completion

Homework completion was assessed using the homework sheets that were administered weekly and was consistent with the PCIT protocol and thus comparable across the two studies. Mothers were instructed to engage in daily practice at home in between sessions, which included a 5-min child-led play session to practice using the “do” skills and refraining from using the “don’t” skills. During the Parent-Directed Interaction phase, mothers were also instructed to practice effective commands and the use of time-out in the context of play and other situations. Mothers were asked to record the number of days that they practiced these skills on a weekly homework sheet. When mothers did not bring the homework sheet to the session, therapists inquired about days practiced and recorded the information on the same sheet. When mothers missed a session, these data were collected retrospectively at the following session. The number of days practiced was based on the number of days since the last session to account for missed sessions. To account for opportunities to complete homework, weekly homework completion was calculated by the number of days practiced divided by the total number of days since the last session to yield a homework completion percentage. Weekly homework completion percentages were then averaged to calculate an average homework completion percentage over the course of treatment.

PROCEDURE

Studies A and B were approved by the affiliated Institutional Review Board. Both studies were randomized controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy of PCIT with at-risk groups (i.e., children with developmental delay and children born premature). To determine eligibility criteria (described above), families completed a screening assessment after signing an informed consent form. Families meeting criteria were then randomly assigned to an IT group or WL group. At the pretreatment assessment (for the IT group this was the assessment immediately preceding treatment and for the WL group there was a 4-month waiting period), mothers completed the CBCL and the PSI. Mothers were also videotaped interacting with their child during a 5-min child-directed play and a 5-min clean-up situation. The assessments were completed in the clinic using age-appropriate toys (e.g., blocks, farm house) that were standardized across assessments within each study and were different from the toys used during treatment sessions. During the posttreatment assessment, the assessment immediately after treatment completion, mothers were again asked to complete the CBCL and PSI, and were videotaped interacting with their child during a 5-min child-directed play and a 5-min clean-up situation.

TREATMENT DESCRIPTION

PCIT is a manualized behavioral parent-training intervention (Eyberg et al., 2008). Parents are coached on skills via a one-way mirror using a wireless headset. The Child-Directed Interaction (CDI) phase of treatment focuses on positive parenting techniques, whereas the Parent-Directed Interaction (PDI) phase focuses on effective commands and time-out. In both studies, sessions were conducted once a week for approximately 1 hour by advanced clinical psychology graduate students with weekly supervision. Families in both studies completed an average of 12 PCIT sessions. In both studies, treatment completion was based on PCIT mastery criteria (10 labeled praises, 10 behavior descriptions, 10 reflections, and less than 3 questions, commands, or criticisms). However, in both studies, families participated in a maximum of 5 CDI coach sessions in order to ensure that families participated in some PDI sessions (CDI skills are also coached throughout PDI) by the posttreatment assessment, which was conducted 4 months after the pretreatment assessment. All sessions were videotaped in both studies with 50% of videotapes checked for treatment integrity (97% and 94% for Studies A and B, respectively). The treatment protocols for Studies A and B were identical (Eyberg & Child Study Lab, 1999).

DATA ANALYTIC PLAN

All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 19 (SPSS 19). There were no missing data for any study variables at pretreatment. However, 12 families were missing data for at least one study variable at posttreatment. Reasons for missing data included but were not limited to treatment dropout (n = 12), missing items, etc. According to Little’s Missing Completely at Random test, the data were missing completely at random (χ2 = 55.29, p > .05). Multiple imputation with 10 imputations was conducted, which is sufficient to accurately estimate the data for this sample size (Rubin, 1987). Preliminary data analyses were conducted to examine any associations between demographic variables and any outcome variables used in the current study. Next, independent regression analyses were conducted to examine the extent to which homework completion uniquely predicted changes in child behavior problems, parenting skills, and parenting stress from pre- to posttreatment. Independent regressions controlled for pretreatment levels of the outcome variable in order to reflect changes during treatment. Lastly, indirect effects models were tested with parenting stress as a mediator of the association between homework completion and child and parent outcomes following procedures recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). Due to constraints in performing bootstrapping procedures with imputed datasets in SPSS, we randomly selected one imputation for the indirect effects analyses based on procedures used by Falk and Lee (2012) for highly consistent imputations and previous literature suggesting the robust nature of single imputations (Widaman, 2006). Parameter estimates and confidence intervals for total and indirect effects were generated based on 5,000 random samples. We determined the indirect effect to be statistically significant by a bias-corrected confidence interval for the parameter that did not contain zero.

Results

PRELIMINARY ANALYSES

Analysis of demographic variables revealed associations between child age and pretreatment externalizing behavior problems such that older children had significantly higher levels of externalizing behavior problems than younger children (r = .35, p < .05). Mothers of older children were also more likely to use more “do” skills and less “don’t” skills at posttreatment (rs = .36 and −.30, respectively; ps < .05). Higher child IQ was associated with lower maternal utilization of do skills (r = −.38, p < .01), and higher utilization of don’t skills (r = .33, p < .05) at posttreatment. Therefore, all subsequent analyses controlled for child age and child IQ. No other demographic variables (e.g., child sex, SES, maternal race/ethnicity) were associated with variables of interest. Descriptive statistics for homework completion and outcome measures are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| M | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homework Completion (O) | 57.97 | 20.89 | 8.13 | 91.19 |

| Pre-Treatment CBCL Externalizing Problems Raw Score (P) | 31.06 | 8.02 | 17 | 47 |

| Post-Treatment CBCL Externalizing Problems Raw Score (P) | 16.42 | 8.98 | 3 | 39 |

| Pre-Treatment Do Skills (O) | 5.81 | 5.23 | 0 | 27 |

| Post-Treatment Do Skills (O) | 19.46 | 11.18 | 0 | 45 |

| Pre-Treatment Don’t Skills (O) | 35.54 | 16.16 | 7 | 67 |

| Post- Treatment Don’t Skills (O) | 10.14 | 11.76 | 1 | 54 |

| Pre-Treatment PSI-SF Raw Score (P) | 96.44 | 22.91 | 60 | 155 |

| Post-Treatment PSI-SF Raw Score (P) | 80.04 | 20.24 | 41 | 117 |

| Pre-Treatment Child Compliance (O) | .55 | .22 | 0 | 1 |

| Post-Treatment Child Compliance (O) | .77 | .18 | .27 | 1 |

Note. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist, PSI-SF = Parenting Stress Index-Short Form, O = observed measure, P = parent report.

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN VARIABLES

As displayed in Table 2, partial correlational analyses revealed associations between maternal homework completion and posttreatment externalizing behavior problems (pr = −.48, p < .01), do skills (pr = .36, p < .05), and don’t skills (pr = −.40, p < .05), such that mothers who reported higher homework completion used more do skills and less don’t skills and reported lower levels of externalizing behavior problems in their child at posttreatment. Homework completion was not associated with parenting stress or child compliance at pre- or posttreatment (ps > .05). Additionally, homework completion was not associated with the number of sessions primary caregivers attended (r = −.06, p = .70), thus session attendance was not included as a covariate in subsequent analyses. All other correlations between variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlations between Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Homework Completion (O) | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Pre CBCL Ext. Problems Raw Score (P) | −.07 | - | |||||||||

| 3. Post CBCL Ext. Problems Raw Score (P) | −.48** | .26 | - | ||||||||

| 4. Pre Do Skills (O) | −.18 | −.02 | .06 | - | |||||||

| 5. Post Do Skills (O) | .36* | .22 | −.17 | .45* | - | ||||||

| 6. Pre Don’t Skills (O) | −.06 | −.14 | −.23 | .31* | .14 | - | |||||

| 7. Post Don’t Skills (O) | −.40* | .09 | .22 | −.23 | −.52** | .23 | - | ||||

| 8. Pre PSI-SF Raw Score (P) | .05 | .65** | .37* | .04 | .08 | −.33* | −.21 | - | |||

| 9. Post PSI-SF Raw Score (P) | −.30 | .39* | .67** | .11 | −.10 | −.39* | .03 | .59** | - | ||

| 10. Pre-Treatment Child Compliance (O) | .03 | .06 | .01 | .08 | −.09 | −.08 | −.05 | .06 | −.04 | - | |

| 11. Post-Treatment Child Compliance (O) | .14 | .28 | −.34* | .11 | .26 | .03 | −.23 | .20 | .31 | .11 | - |

Note.

p < .01,

p < .05.

P = parent report, O = observed measure. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist, PSI = Parenting Stress Index-Short Form. All correlations are partial correlations controlling for child age and IQ.

DIRECT EFFECT OF PARENTAL HOMEWORK COMPLETION

Regression analyses were conducted to examine the unique effect of parental homework completion on changes in child behavior problems and parenting skills while accounting for initial levels of the outcome variable (to assess change), as well as child age and child IQ (covariates entered in step 1 and homework entered in step 2 of the equations). As illustrated in Table 3, maternal homework completion significantly predicted changes in do skills (β = .39, p < .01). Mothers who reported to engage in more homework practice significantly increased their utilization of do skills at the end of treatment. Homework completion did not significantly predict changes in don’t skills (β = −.27, p > .05). However, maternal homework completion significantly predicted changes in parenting stress (β = −.36, p < .05), such that mothers who reported to engage in more homework practice reported greater decreases in parenting stress at the end of treatment. As displayed in Table 4, maternal homework completion also predicted changes in child externalizing behavior problems (β = −.40, p < .05), such that mothers who reported to complete more home practice reported greater decreases in child externalizing behavior problems at the end of treatment. Maternal homework completion did not predict changes in observed child compliance (β = .14, p > .05).

Table 3.

Model for Predicting Parent Outcomes

| β | T-value | Model R2 | R2 Change | F Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Treatment Do Skills (P) | |||||

| Step 1. Pre-Treatment Do Skills (P) | .37** | 2.83 | .32 | .32 | 7.03* |

| Child IQ (O) | −.29* | −2.01 | - | - | - |

| Child Age (O) | .25 | 1.76 | - | - | - |

| Step 2. | - | - | .44 | .12 | 8.77* |

| Homework Completion (O) | .39** | 2.77 | - | - | - |

| Post-Treatment Don’t Skills (P) | |||||

| Step 1. Pre-Treatment Don’t Skills (P) | .19 | 1.16 | .19 | .19 | 3.55 |

| Child IQ (O) | .22 | 1.51 | - | - | - |

| Child Age (O) | −.20 | −1.26 | - | - | - |

| Step 2. | - | - | .26 | .07 | 4.35 |

| Homework Completion (O) | −.27 | −1.65 | |||

| Post-Treatment Parenting stress (P) | |||||

| Step 1. Pre-Treatment PSI-SF Raw Score (P) | .59*** | 4.28 | .37 | .37 | 8.88** |

| Child IQ (O) | −.10 | −.51 | - | - | - |

| Child Age (O) | −.09 | −.65 | - | - | - |

| Step 2. | - | - | .46 | .09 | 7.20* |

| Homework Completion (O) | −.36* | −2.02 | - | - | - |

Note.

p < .01,

p < .05.

P = parent report, O = observed measure. PSI = Parenting Stress Index- Short Form.

Table 4.

Model for Predicting Child Outcomes

| β | T-value | Model R2 | R2 Change | F Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Treatment Externalizing Behavior Problems (P) | |||||

| Step 1. Pre-Treatment CBCL Externalizing Raw Score (P) | .26 | 2.39 | .10 | .10 | 1.69 |

| Child IQ (O) | −.01 | −.05 | - | - | - |

| Child Age (O) | −.20 | −1.10 | - | - | - |

| Step 2. | - | - | .25 | .15 | 8.52* |

| Homework Completion (O) | −.40* | −2.13 | - | - | - |

| Post-Treatment Child Compliance (O) | |||||

| Step 1. Pre-Treatment Child Compliance (O) | .10 | .63 | .20 | .20 | 2.89 |

| Child IQ (O) | −.22 | −1.29 | - | - | - |

| Child Age (O) | .28 | 1.58 | - | - | - |

| Step 2. | - | - | .22 | .02 | .59 |

| Homework Completion (O) | .14 | .76 | - | - | - |

Note.

p < .01,

p < .05.

P = parent report, O = observed measure. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist.

INDIRECT EFFECT OF PARENTING STRESS

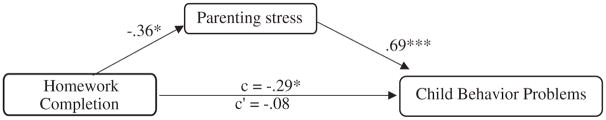

Given the independent associations of maternal homework completion and changes in parenting stress as predictors of changes in child behavior problems (β = −.45, p < .05; β = .76, p < .001, respectively), an indirect effects model was tested. Specifically, we examined the indirect effect of parenting stress on the association between maternal homework completion and reductions in child behavior problems.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the total effect of homework completion on child externalizing behavior problems was significant (c = −.29, p < .05). However, once adjusting for changes in parenting stress, the direct effect of homework completion was no longer significant (c’ = −.08, p > .05). The indirect effect (ab = −.21) was statistically significant as the bias corrected confidence interval did not contain zero with a lower limit of −.54 and upper limit of −.07. Indirect effects models for do skills, don’t skills, and child compliance as outcomes were not conducted due to lack of significant associations for all paths.

FIGURE 1.

An indirect effects model of the association between parental homework completion and decreases in child behavior problems (CBCL externalizing raw score) via parenting stress (PSI-SF total raw score). Standardized regression coefficients are provided along the paths. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

Findings from this study support our hypothesis that maternal homework completion had a positive impact on treatment outcomes during BPT for children with or at risk for developmental delay. Increased levels of homework completion was found to predict lower levels of child externalizing behavior problems, as well as higher levels of positive parenting skills and lower levels of parenting stress. However, homework completion did not predict changes in utilization of don’t skills or observed child compliance.

This study addressed a considerable gap in the literature by demonstrating the effect of maternal homework completion on child and parent outcomes during PCIT. While there is evidence to suggest the utility of homework completion in other BPT interventions, there is limited research on its function in PCIT and no research with samples of children with or at risk for developmental delay. Our results are consistent with previous work demonstrating an association between homework completion during group-based BPT programs and improvements in child behavior (Clarke et al., 2013; Kling et al., 2010; Tynan et al., 2004) and parenting skills (Baydar et al., 2003). These results suggest that homework practice in PCIT, which utilizes in-vivo coaching, provides additive significant effect on treatment outcomes that is similar to other BPT models that do not involve in-vivo coaching. A recent meta-analysis suggested that assigning homework was not a beneficial component of BPT programs, whereas larger effect sizes were associated with interventions that provide opportunities for parents to practice skills during sessions with their own child (Kaminski et al., 2008). However, this meta-analysis included a wide range of programs, including prevention programs, which may explain why our study and previous work on other parent-training programs have identified homework completion as a unique predictor of treatment outcomes. It may be the case that homework plays a larger role in treatment rather than prevention programs as severity levels have been found to be predictive of parental treatment adherence (Bennett, Power, Rostain, & Carr, 1996).

An indirect effects model was tested and revealed that decreases in parenting stress served as a potential mechanism by which homework completion was associated with reductions in child behavior problems. Although both variables were collected at posttreatment, interpretations were based on an indirect effects model in an exploratory manner. A plausible explanation for why homework completion serves to reduce parenting stress in this at-risk population may be that home practice of skills learned in BPT may serve to increase parenting self-efficacy, which has been implicated as a factor responsible for changes in parenting stress (Erdwins et al., 2001; Gross, Fogg, & Tucker, 1995; Scheel & Rieckmann, 1998), parenting competence, and child outcomes (see Jones & Prinz, 2005, for a review) during BPT. Others have proposed a transactional model to represent the association between parental self-efficacy, treatment adherance, and acquisition of skills (Mah & Johnston, 2008). Future research should examine how homework completion impacts parenting self-efficacy and subsequent parenting stress and treatment outcomes in order to explore the directionality of these associations. Additionally, when comparing mothers of preschoolers with and without developmental delay, levels of well-being are lowest among mothers of children with developmental delay and co-occurring behavior problems (Baker, Blacher, & Olsson, 2005), further highlighting the importance of examining factors related to parenting efficacy and parental mental health in this at-risk population.

Previous work identifying parenting stress as a predictor of parent-child interaction quality (Crnic, Gaze, & Hoffman, 2005) provides support for an additional explanation for the indirect effect of parenting stress. Perhaps reductions in parenting stress help to explain the association between homework and child behavior because reduced parenting stress may serve to enhance the parent-child interaction. Harwood and Eyberg (2006) identified a latent construct of parent-child dysfunctional interaction comprised of parenting stress, child disruptive behavior, and parenting practices, highlighting the importance of all three constructs in contributing to the quality of parent-child interactions. Together these findings support the notion that decreases in parenting stress as a result of increased practice of positive parenting techniques may lead to positive child outcomes by indirectly enhancing interactional factors.

Another possible reason that homework led to reductions in child behavior problems is because parents increased the amount of time they spent with their child, which may contribute to the reduction of parenting stress. Parents of children with developmental delay may engage in interactions that focus primarily on caretaking; therefore, the increase in positive parent-child interactions in the context of child-directed play via homework completion during BPT may have contributed to the reduction of parenting stress. Although studies show that increased parental utilization of do skills is related to decreases in child behavior (Bagner & Eyberg, 2007), limited studies have examined the additive effects of do skills beyond more interactional variables such as warmth and responsiveness. Factors such as parental responsiveness have been deemed to be critical in the development of parent-child interactions for children with developmental delay (see Warren & Brady, 2007, for a review).

It is important to acknowledge that the interpretations that may be drawn from our findings are limited by the timing of variables collected in the indirect effects model. Although the model controlled for pretreatment scores, both child behavior problems and parenting stress were collected at posttreatment. Although we proposed that homework completion is associated with changes in parenting stress, which is subsequently associated with changes in child behavior, an alternate pathway may also be considered. Given work demonstrating the influence of child behavior on parenting behaviors (Silverman, Kurtines, Jaccard, & Pina, 2009), it may be plausible for homework completion to indirectly influence parenting stress through child behavior problems. Of note, the indirect effects model was not significant when tested with child behavior as the mediating variable. However, due to our small sample size and lack of temporal precedences our conclusions are limited.

The majority of studies examining the effects of BPT on child conduct problems utilize parent report of behavior problems. While our findings were consistent with previous research examining the effect of parental homework completion on decreased parent reported externalizing behavior problems, we did not find a significant effect with observed child compliance. These findings further support the idea that homework completion may help reduce parental perceptions of child behavior problems but not to reduce observed child behavior, as quantified by compliance to parental commands. However, experimental studies have found children of mothers that are taught to use mirroring and praise are more compliant during observations (Wahler & Meginnis, 1997). These findings highlight the importance of considering parental skill level when examining compliance. Nevertheless, observed compliance may be more readily affected by parental skill level during home practice than parental reports of behavior change.

There are limitations to the generalizability of results revealed in the current study that need to be addressed. The sample in this study included children with or at risk for developmental delay—therefore, findings may not generalize to typically developing children with externalizing behavior problems. Nevertheless, this study is the first to examine homework completion during PCIT with a high-risk sample and is important given previous research on heightened stress levels in parents of children with developmental delay (Baker et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2003; Estes et al., 2009), which may amplify the indirect effect of maternal stress revealed in this study. Furthermore, results of the current study may be more generalizable to other high-stress populations, which have been identified to be at higher risk for worse treatment outcomes (Bagner & Graziano, 2013; Fernandez & Eyberg, 2009). Nevertheless, future studies should also examine the role of homework and parenting stress in typically developing children with elevated behavior problems

Another limitation of the current study is the racial homogeneity of the sample consisting of 78% White families. Risk factors that affect treatment attrition and response, including parenting stress, are overrepresented among ethnic and racial minorities (Kazdin, Stolar, & Marciano, 1995). Utilizing a more diverse sample may result in a larger effect of homework completion on outcomes. Nonetheless, research examining PCIT with racially and ethnically diverse populations has found considerable treatment effects (Fernandez, Butler, & Eyberg, 2011; Matos et al., 2006; McCabe, Yeh, Garland, Lau, & Chavez, 2005) and outcomes comparable with White children (Capage, Bennett, & McNeil, 2001).

Additionally, it is important to acknowledge that our findings may have been partially attributed to shared reporter bias as parents reported both their own level of stress, as well as their child’s behavior problems. Some studies have extended the effects of homework completion beyond parent report, such as teacher-reported reductions in child behavior problems (Villodas et al., 2014), and future research should incorporate reports of child behavior from multiple informants. Outcome variables were also limited to two time points, weakening support for an indirect effect, and future research should examine the indirect effect of parenting stress with additional time points. Obtaining homework completion records that also rely on parents as informants presents yet another challenge. Others have utilized grading systems to differentiate between homework attempt and completion (Clarke et al., 2013). Nonetheless, these more rigorous systems also rely on parent report.

Data were not collected on whether or not parent(s) completed the homework sheets at home before each session or retrospectively during each session (consistent with PCIT protocol, if families did not bring in and/or complete the homework sheet, the therapist asked the parent to complete the homework sheet at the beginning of the session). The lack of information about when and where homework sheets were completed raises concerns about the potential bias of the report of homework completion. Future studies should examine how such parental bias may affect homework reports by comparing the potential differential effect that homework completion has on outcomes for families that bring homework sheets completed prior to the session and families that complete homework sheets at the beginning of the session. Additionally, the fidelity with which parents were practicing skills at home was unknown. Therefore, future work should focus on examining whether fidelity of homework implementation plays a role in predicting outcomes. Future studies should also focus on developing more reliable and valid mechanisms by which to measure parental homework completion. For example, a diary approach to collecting homework data via smartphone technology may be a useful approach, as recent research has identified the growing utility of phone applications that focus on aspects of behavioral PT (Jones, Forehand, McKee, Cuellar, & Kincaid, 2010).

An additional limitation of the study was the reliance on maternal report. Father involvement was not examined in the current study. Studies find that involvement of fathers in BPT may be conducive for the long-term maintenance of treatment outcomes (Bagner, 2013; Bagner & Eyberg, 2003). Aspects of BPT such as homework may be especially susceptible to the effects of paternal involvement because completing homework requires a great deal of adherence outside of treatment. Additionally, given our focus on parenting stress, along with previous work demonstrating associations between father involvement and maternal stress (Cooper, McLanahan, Meadows, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009), it may be beneficial for future studies to examine how the mediating role of parental stress may function differently for families with higher or lower levels of parental co-involvement in treatment.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides preliminary evidence to suggest that homework completion is clinically useful for predicting favorable parent and child outcomes in PCIT. Specifically, homework completion was found to predict better parent and child treatment outcomes in a sample of children with or at risk for developmental delay. These findings further highlight the clinical utility of homework completion in high-risk groups in which clinical severity and parental factors associated with treatment dropout are heightened. Lastly, our study found that parenting stress partially explained the link between homework completion and child outcomes. Hence, it appears that homework completion may serve as a way to reduce parenting stress. This finding may have important clinical implications for mental health professionals to not only emphasize homework completion to parents as having a positive impact on their child’s behavior but also on reduced stress by interacting more frequently with their children during play.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH career development award (K23 MH085659), as well as pre- and postdoctoral training awards from the NIMH and NICHD (F31 MH068947 and F32 HD056748), respectively.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abidin R. Parenting Stress Index Manual. 3. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual of the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anastopoulos AD, Shelton T, DuPaul GJ, Guevremont DC. Parent training for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Its impact on parent functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:581–596. doi: 10.1007/BF00916320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00916320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM. Father’s role in parent training for children with developmental delay. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27(4):650. doi: 10.1037/a0033465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0033465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Eyberg SM. Father involvement in parent training: When does it matter? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(4):599–605. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Eyberg SM. Parent-child interaction therapy for disruptive behavior in children with mental retardation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36(3):418–429. doi: 10.1080/15374410701448448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374410701448448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Graziano PA. Barriers to success in parent training: The role of cumulative risk. Behavior Modification. 2013;37:356–377. doi: 10.1177/0145445512465307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0145445512465307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Sheinkopf SJ, Vohr BR, Lester BM. Parenting intervention for externalizing behavior problems in children born premature: An initial examination. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP. 2010;31(3):209. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181d5a294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181d5a294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Crnic KA, Edelbrock C. Behavior problems and parenting stress in families of three-year-old children with and without developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2002;107(6):433–444. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2002)107<0433:BPAPSI>2.0.CO;2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edelbrock C, Low C. Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47(4–5):217–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00484.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Olsson MB. Preschool children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems, parents’ optimism and well-being. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49:575–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00691.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C. The role of mental health factors and program engagement in the effectiveness of a preventive parenting program for head start mothers. Child Development. 2003;74(5):1433–1453. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00616. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. 3. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Power TJ, Rostain AL, Carr DE. Parent acceptability and feasibility of ADHD interventions: Assessment, correlates, and predictive validity. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1996;21(5):643–657. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.5.643. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/21.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capage LC, Bennett GM, McNeil CB. A comparison between African American and Caucasian children referred for treatment of disruptive behavior disorders. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2001;23(1):1–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J019v23n01_01. [Google Scholar]

- Censullo M. Developmental delay in healthy premature infants at age two years: Implications for early intervention. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 1994;15(2):99–104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004703-199404000-00006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Anderson L, Wymbs BT, Wymbs FA. Parent-endorsed reasons for not completing homework in group-based behavioural parent training for high-risk families of youth with ADHD. Behaviour Change. 2013;30(4):262–272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/bec.2013.25. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis AM, Chacko A, Fabiano GA, Wymbs BT, Pelham WE. Enhancements to the behavioral parent training paradigm for families of children with ADHD: Review and future directions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7:1–27. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000020190.60808.a4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:CCFP.0000020190.60808.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AT, Marshall SA, Mautone JA, Soffer SL, Jones HA, Costigan TE, Power TJ. Parent attendance and homework adherence predict response to a family–school intervention for children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.794697. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.794697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cooper CE, McLanahan SS, Meadows SO, Brooks-Gunn J. Family structure transitions and maternal parenting stress. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(3):558–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00619.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Gaze C, Hoffman C. Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development. 2005;14:117–132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/icd.384. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MC, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43(8):1087–1098. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodrill CB. An economical method for the evaluation of general intelligence in adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49(5):668–673. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.5.668. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.49.5.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodrill CB. Long-term reliability of the Wonderlic Personnel Test. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(2):316–317. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.1.145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdwins C, Buffardi L, Casper W, O’Brien A. The relationship of women’s role strain to social support, role satisfaction, and self-efficacy. Family Relations. 2001;50(3):230–238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2001.00230.x. [Google Scholar]

- Estes A, Munson J, Dawson G, Koehler E, Zhou XH, Abbott R. Parenting stress and psychological functioning among mothers of preschool children with autism and developmental delay. Autism. 2009;13(4):375–387. doi: 10.1177/1362361309105658. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1362361309105658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM Child Study Lab. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: Integrity Checklists and Materials. 1999 Retrieved from the University of Florida Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Web site: http://www.pcit.org.

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg S, Nelson M, Duke M, Boggs S. Manual for the Dyadic Parent–Child Interaction Coding System. (3) 2004 Retrieved from the University of Florida Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Web site: http://www.pcit.org.

- Falk AE, Lee SS. Parenting behavior and conduct problems in children with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Moderation by callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2012;34(2):172–181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10862-011-9268-z. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MA, Butler AM, Eyberg SM. Treatment outcome for low socioeconomic status african american families in parent-child interaction therapy: A pilot study. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2011;33(1):32–48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2011.545011. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MA, Eyberg SM. Predicting treatment and follow-up attrition in parent–child interaction therapy. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(3):431–441. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9281-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Fogg L, Tucker S. The efficacy of parent training for promoting positive parent-toddler relationships. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18(6):489–499. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180605. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood MD, Eyberg SM. Child-directed interaction: Prediction of change in impaired mother-child functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(3):335–347. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9025-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9025-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskett ME, Ahern LS, Ward CS, Allaire JC. Factor structure and validity of the parenting stress index-short form. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(2):302–312. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Watanabe HD, Richters JE, Roper M, Hibbs ED, Salzberg AD, et al. Scales, diagnoses, and child psychopathology: II. Comparing the CBCL and the DISC against external validators. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24:151–168. doi: 10.1007/BF01441482. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01441482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TL, Prinz RJ. Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:341–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, McKee LG, Cuellar J, Kincaid C. Behavioral parent training: Is there an “app” for that? the Behavior Therapist. 2010;33(4):72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(4):567–589. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis N, Deane FP, Ronan KR, L’Abate L. Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy. New York: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Stolar MJ, Marciano PL. Risk factors for dropping out of treatment among white and black families. Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9(4):402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.9.4.402. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SC, Kim JS, Tripodi SJ, Brown SM, Gowdy G. Does Parent-Child Interaction Therapy reduce future physical abuse? A meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice. 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049731514543024.

- Kling Å, Forster M, Sundell K, Melin L. A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of parent management training with varying degrees of therapist support. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(4):530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.02.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert N, Nihira K, Leland H. Manual for the Adaptive Behavior Scale–School. 2. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1997;33:159–74. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2529310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AR, Budd KS. A community mental health implementation of Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(5):654–668. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9353-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10826-010-9353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah JWT, Johnston C. Parental social cognitions: Considerations in the acceptability of and engagement in behavioral parent training. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11:218–236. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0038-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10567-008-0038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M, Torres R, Santiago R, Jurado M, Rodríguez I. Adaptation of parent-child interaction therapy for Puerto Rican families: A preliminary study. Family Process. 2006;45(2):205–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00091.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Lau AS, Chavez G. The GANA program: A tailoring approach to adapting parent child interaction therapy for mexican americans. Education & Treatment of Children. 2005;28(2):111–129. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre LL, Abbeduto L. Parent training for young children with developmental disabilities: Randomized controlled trial. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113:356–368. doi: 10.1352/2008.113:356-368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nix RL, Bierman KL, McMahon RJ. How attendance and quality of participation affect treatment response to parent management training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):429–438. doi: 10.1037/a0015028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0015028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Ferriter C. Parent management of attendance and adherence in child and adolescent therapy: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-4753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Lachar D, Loveland KA, Santos CW, Faria LP, Azzam PN, Cleveland LA. Patterns of behavioral adjustment and maladjustment in mental retardation: Comparison of children with and without ADHD. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2000;105(4):236–251. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2000)105<0236:POBAAM>2.0.CO;2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2000)105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Jr, Fabiano GA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):184–214. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818681. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374410701818681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisterman S, Firestone P, McGrath P, Goodman JT, Webster I, Mallory R, Goffin B. The role of parent training in treatment of preschoolers with ADDH. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1992;62(3):397–408. doi: 10.1037/h0079356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0079356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitman D, Currier RO, Stickle TR. A critical evaluation of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) in a head start population. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(3):384–392. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyno SM, McGrath PJ. Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problems—A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01544.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Mazzucchelli T, Studman L, Sanders M. Behavioral family intervention for children with developmental disabilities and behavioral problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:180–193. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Hillsdale, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Scheel MJ, Rieckmann T. An empirically derived description of self-efficacy and empowerment for parents of children identified as psychologically disordered. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 1998;26(1):15–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01926189808251083. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, SchwabStone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Kurtines WM, Jaccard J, Pina AA. Directionality of change in youth anxiety treatment involving parents: an initial examination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):474. doi: 10.1037/a0015761. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0015761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tynan WD, Chew C, Algermissen M. Concurrent parent and child therapy groups for externalizing disorders: The rural replication. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2004;11(1):99–101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229(04)80012-9. [Google Scholar]

- Upshur C, Wenz-Gross M, Reed G. A pilot study of early childhood mental health consultation for children with behavioral problems in preschool. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2009;24(1):29–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.12.002. [Google Scholar]

- Villodas MT, McBurnett K, Kaiser N, Rooney M, Pfiffner LJ. Additive effects of parent adherence on social and behavioral outcomes of a collaborative school–home behavioral intervention for ADHD. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2014;45(3):348–360. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0405-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0405-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahler RG, Meginnis KL. Strengthening child compliance through positive parenting practices: What works? Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(4):433–440. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2604_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SF, Brady NC. The role of maternal responsivity in the development of children with intellectual disabilities. Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews. 2007;13(4):330–338. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Abbreviated Intelligence Scale (WASI) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Third Edition. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF. Best practices in quantitative methods for developmentalists: III. Missing data: What to do with or without them. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71:42–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2006.07103001.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.15405834.2006.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]