Abstract

Background

Group sex has been suggested as a potential high-risk setting for HIV and other STIs among men who have sex with men (MSM). We investigated whether group sex is associated with lower condom use during anal sex and higher proportions of STIs compared to dyadic sex among HIV-negative MSM between 2009–2012.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from 7 data waves of the Amsterdam Cohort Studies were used. The sample consisted of 465 MSM who either reported both group and dyadic sex (at n=706 visits) or dyadic sex only (at n=1339 visits) in the preceding 6 months. Logistic regression with generalized estimating equations was used to investigate the association between sexual setting (group versus dyadic sex), condomless anal sex, and STI.

Results

Group sex was reported at 35% (706/2045) of visits. Condomless sex was more often reported during dyadic than group sex, OR=3.64 (95%CI=2.57–5.16). Men who had group sex were more likely diagnosed with Gonorrhea compared to men with dyadic sex, OR=1.71 (95%CI=1.08–2.97), but this effect was not retained in the multivariate model.

Conclusions

Results demonstrate within-person differences in sexual behavior during group and dyadic sex among MSM. Men were more likely to use condoms during group sex than dyadic sex. Thus, for some, group sex may not necessarily be risky for HIV infection compared to dyadic sex. However, group sex may be a higher-risk setting for acquiring STIs other than HIV, such as Gonorrhea. Group sex encounters should be recognized as distinct sexual settings with specific risk characteristics that need to be addressed accordingly.

Keywords: group sex, dyadic sex, condomless anal sex, MSM

INTRODUCTION

Men who have sex with men (MSM) continue to be at high risk of acquiring HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI)1,2. In the last few decades STI rates increased among MSM populations in high-income countries3–5, suggesting a rise in sexual risk behaviour6–8. Many epidemiological and psychosocial studies have found that important behavioral risk factors for acquiring HIV and STI are condomless anal sex with casual partners and a high turnover of sexual partners9–11.

One of the casual sex settings involving a high turnover of sexual partners is group sex. During group sex men have the opportunity to engage in many different sexual acts with different partners within a short period of time, thus enhancing the probability of exposure to HIV and other STIs12,13. Studies among MSM engaging in group sex found proportions of condomless anal sex between 25%–55%14–18. Engaging in group sex was also associated with frequent reports of illicit drug use to enhance sexual experience19,20.

Yet, information on group sex activities and their health impact on MSM is limited and there is little insight into whether the same men behave differently during group sex with casual partners in comparison to sex with one casual partner at a time (dyadic sex). The little data available suggests that among MSM who reported both group and dyadic sex, during group sex men were more likely to engage in condomless anal sex and report more casual partners than during their one-on-one encounters20.

The aims of the present study were to determine the proportion of HIV-negative MSM within the Amsterdam Cohort Studies (ACS) who engaged in group sex over a 3-year period (2009–2012). We also investigated among the same men whether group sex is associated with lower use of condoms during anal sex and higher prevalence of STIs compared to casual dyadic sex, independent of drug and alcohol use. We furthermore examined, among men with multiple group sex reports over time, whether having more extensive and consistent experience with group sex would have affected men’s behavior in this setting.

METHODS

Study Procedures

The ACS among MSM started in 1984 and is an open on-going prospective cohort to investigate the epidemiology, psycho-social determinants, course of infection, and pathogenesis of HIV, and to evaluate the effect of interventions among HIV-negative and HIV-positive MSM21. Men are eligible to participate in the cohort if they are living in or around Amsterdam and have had at least one male sexual partner in the preceding 6 months. Men are recruited into the ACS by “convenience sampling” (e.g., brochures at the STI clinic, advertisements in the gay scene) and “chain referral sampling” (participants recruited by other participants)9.

Participants visit the Public Health Service of Amsterdam every 6 months to complete a self-administered questionnaire regarding their sexual (risk) behavior in the preceding 6 months. At each study visit, blood is drawn to test for HIV and Syphilis and for storage. Questions regarding demographics are asked at the very first visit. From 2008 onwards 6-monthly STI screenings were included in the assessments. Self anal swabs and urine samples are collected to test for anal and urethral Gonorrhea and Chlamydia and a research nurse collects throat swabs from each participant to detect the presence of pharyngeal Gonorrhea and Chlamydia.

HIV-antibodies testing is done using two commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (AxSYM; Abbot Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA; Vironostika, Organon Teknika, Boxtel, the Netherlands). To diagnose Gonorrhea and Chlamydia, a nucleic acid amplification test (Gen-Probe Aptima Combo 2 Assay, Gen-Probe Incorporated, San Diego, CA) is used. Serum is screened for Syphilis antibodies (Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay; Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan). The Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) test and the FTA-absorption test (Nosticon and Trepo-spot IF; Biomérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) are performed to diagnose, confirm, and classify Syphilis infection.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Study sample

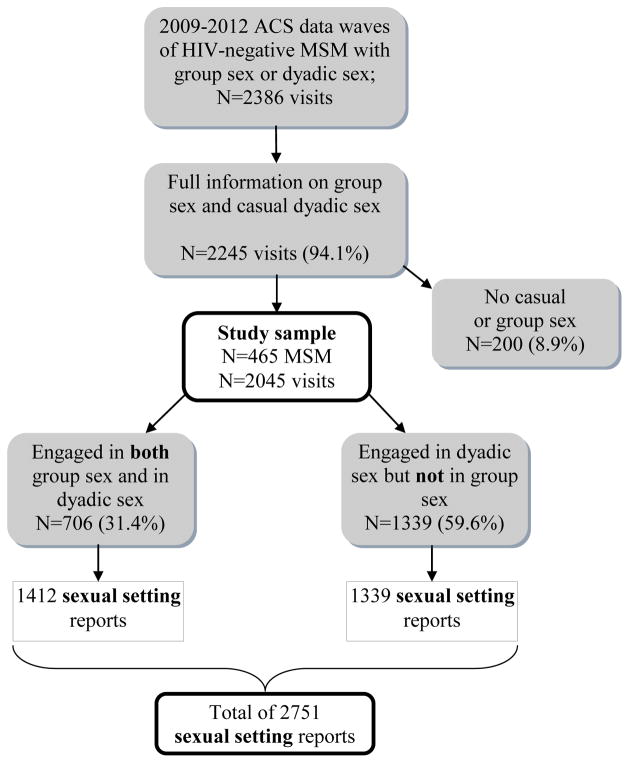

We used data from seven data waves of the ACS collected between 2009 and 2012. In total, 465 MSM who were HIV-negative at baseline participated in the cohort in this period. Nine men (2%) HIV-seroconverted during the study period; of those men all data collected before their first HIV-positive ACS visit was used. The participants had a total of 2386 visits at which they provided information on dyadic sex (yes/no) and group sex with casual partners (yes/no) in the preceding 6 months (Figure 1). At 94% (2245/2386) of these visits MSM provided information on anal intercourse. We included 706 (31%) visits where MSM reported both group sex and casual dyadic sex and 1339 (60%) visits where MSM reported only casual dyadic sex. The 200 (9%) visits where MSM reported neither casual sex partners nor group sex were excluded from the analyses. Such periods of no sexual encounters were less likely to occur among men who had ever reported group sex than among men who had only reported dyadic sex partners during the study period (X2=28.03, df=1, p<0.001). The total sample consisted of 2045 visits of 465 individual MSM, with a median number of 5 visits (IQR=3–6). Data on STI were available for 460 individual MSM, with a total of 2001 (98%) visits.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram

Measures

Outcome measures

Condomless anal sex with casual sex partners

Participants were asked whether they had practiced insertive and/or receptive anal sex during group sex and/or during dyadic sex in the preceding 6 months and whether a condom was used during group sex and/or dyadic sex (ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always’ on a 5-point scale). Condomless anal sex with casual partners was defined as no or inconsistent condom use.

Sexually transmitted infection (STI)

Having an STI (yes/no) was defined as being diagnosed with one or more of the following STIs: Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, or infectious Syphilis.

Main independent variable: sexual setting

Group sex was defined as a sexual encounter with more than one casual sexual partner at the same time. Dyadic sex referred to sex with one casual sex partner at a time. As condomless sex is measured in the cohort per partner and setting type (e.g., casual partner, steady partner, group sex) we constructed a sexual setting predictor variable with three categories; 1) group sex; 2) dyadic sex among those who also reported group sex; and 3) dyadic sex only to investigate the association with condomless sex. As STI diagnoses cannot be linked back to a specific partner type or sexual setting, the sexual setting variable was dichotomized into men who reported both group sex and dyadic sex versus men who reported dyadic sex only to investigate the association with STI.

Co-variables

Co-variables included age, ethnic origin, educational level, sexual orientation, number of casual partners in the preceding 6 months, drug and alcohol use during sex, and having a steady partner in the preceding 6 months.

Age was categorized into 3 categories, based on tertiles; “<34”, “34–40” and “>40”. Ethnic origin was categorized into two categories, “Western European origin” and “Non-Western European origin”. Educational level was considered “high” with completion of higher vocational education or university, and “middle and low” with completion of secondary vocational education, high school, basic vocational education, or primary school. Sexual orientation was measured on a 7-point Kinsey scale, ranging from 0 “exclusively heterosexual” to 6 “exclusively gay”. As most participants identified themselves as exclusively gay, sexual orientation was dichotomized into “exclusively gay” (value 6) and “not exclusively gay” (values 0–5). Number of casual partners in the preceding 6 months was divided into three categories based on tertiles; “less than 5”, “5–12”, and “more than 12”. Participants reported on drug and alcohol use during group sex and dyadic sex. Drug use during sex was defined as any drug reported in each of the sexual settings in the preceding 6 months (yes/no).

Consistent engagement in group sex

Consistent engagement in group sex was defined as having reported group sex at 4 or more consecutive study visits (with a maximum of 7 visits).

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics of men who reported group sex and men who had dyadic sex only were compared using Chi-square tests for categorical data and Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous data.

Drug use and alcohol use were compared between the three sexual settings at baseline using Chi-square tests with Bonferroni corrected post-hoc analyses.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the association between sexual setting and condomless sex on the one hand and sexual setting and STI on the other. Based on previous studies13–16, the multivariate models included variables that were considered potential confounders for the association between engaging in group sex and condomless anal sex: number of casual partners, age, ethnic origin, educational level, sexual orientation, and having a steady partner. We also checked for interactions between sexual setting and the variables age, ethnic origin, and education. As for the use of drugs and alcohol, we additionally assumed that the relation between substance use and sexual setting is a bi-directional one: the use of substances, in the pursuit of sexual pleasure, might influence the decision to engage in group sex but at the same time participation in such encounters may be predictive for substance use. Therefore, multivariate models were run with and without the variables drug and alcohol use to examine the impact of these variables on the relation between sexual setting and condomless sex and STI.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to account for within-participant correlations between the repeated behavioral measures over time and between the sexual behaviors reported within each sexual setting, assuming an unstructured correlation matrix. All analyses were performed with SPSS 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

Participants had a median age of 36 (IQR=32–41), the majority (93%) was of Western European origin, had an educational level of college degree or higher (75%), and identified as exclusively gay (76%). More than half (58%) of the participants had a steady partner (Table 1). At baseline (2009), 170 MSM (37%) reported having had both group sex and dyadic sex and 295 MSM (63%) reported dyadic sex only. Men who reported both group sex and dyadic sex were significantly older, were more likely to have a steady partner and had more casual sex partners in the preceding six months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to sexual behavior of 465 HIV-negative MSM who engaged in group sex and/or dyadic casual sex, Amsterdam Cohort Studies, 2009–2012, the Netherlands.

| Total | Sexual behavior in the preceding 6 months

|

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement in both group sex and dyadic sex | Engagement in dyadic sex only | |||

|

|

|

|

||

| N=465 MSM | N=170 MSM | N=295 MSM | ||

| Age Median (IQR) | 36.1 (31.9–41.1) | 37.0 (32.7–42.4) | 35.7 (31.3–40.5) | 0.027 |

| Ethnic origin* | ||||

| Western European origin | 430/461 (93%)** | 156/168 (93%) | 247/293 (94%) | 0.786 |

| Non-Western European origin | 31/461 (7%) | 12/156 (7%) | 19/293 (7%) | |

| Educational level* | ||||

| College degree | 339/452 (75%) | 121/164 (74%) | 218/288 (76%) | 0.651 |

| Less than college degree | 113/452 (25%) | 43/164 (26%) | 70/288 (24%) | |

| Sexual orientation* | ||||

| Exclusively gay | 339/449 (76%) | 122/165 (74%) | 217/284 (76%) | 0.558 |

| Not exclusively gay | 110/449 (25%) | 43/165 (26%) | 67/284 (24%) | |

| Have a steady partner* | 262/453 (58%) | 110/167 (66%) | 152/286 (53%) | 0.008 |

| Number of casual partners | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (5–22) | 11 (5–23) | 4 (2–7) | 0.000 |

Totals might not add up due to missing values.

In calculation of percentages, missing values were excluded.

IQR, inter quartile range.

Proportions of drug and alcohol use during sex

Proportions of drug use were highest during dyadic sex encounters among men who also had group sex: 69% (116/168); during group sex encounters it was 49% (83/168). For men who had dyadic sex only it was 37% (105/288). Differences between the three sexual settings were statistically significant (p<0.05). Proportions of alcohol use were also highest during dyadic sex encounters: 50% (84/169) among men who also had group sex and 43% (124/287) among men who had no group sex. The proportion of men who used alcohol during group sex encounters was 27% (467/169). Differences between the three sexual settings were statistically significant (p<0.05).

Association between sexual setting and condomless sex

Bivariate and multivariate analyses revealed that condomless sex was more frequently reported during dyadic sex than during group sex (Table 2). No statistically significant difference in condomless sex was found between the two dyadic sex settings.

Table 2.

Bivariate and multivariate analyses of determinants of condomless anal sex with casual partners using logistic regression analysis with generalized estimating equations (GEE) in 2751 sexual behavior reports among 465 MSM, Amsterdam Cohort Studies, 2009–2012, the Netherlands.

| Proportion of condomless sex n/N (%) | Bivariate | Multivariate* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | ORadj (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| Group sex versus dyadic sex** | ||||||

| Visits at which men reported both group sex and dyadic sex | During group sex | 73/706 (10.3) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| During dyadic sex | 222/706 (31.4) | 3.64 (2.57–5.16) | 3.84 (2.21–6.69) | |||

| Visits at which men who reported dyadic sex only | 379/1339 (28.3) | 3.09 (1.55–6.17) | 5.19 (3.10–8.71) | |||

| Number of casual partners** | ||||||

| <5 | 166/873 (19.0) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.009 | |

| 5–12 | 220/864 (25.5) | 1.48 (1.17–1.88) | 1.52 (1.12–2.07) | |||

| >12 | 279/984 (28.4) | 1.62 (1.21–2.17) | 1.25 (0.47–3.27) | |||

| Drug use during sex** | ||||||

| No | 207/1198 (17.3) | 1 | 0.136 | 1 | 0.634 | |

| Yes | 431/1448 (29.8) | 1.68 (0.85–3.32) | 1.17 (0.62–2.21) | |||

| Alcohol use during sex** | ||||||

| No | 291/1480 (19.7) | 1 | 0.216 | 1 | 0.676 | |

| Yes | 349/1175 (29.7) | 1.35 (0.84–2.18) | 1.08 (0.75–1.55) | |||

| Steady partner** | ||||||

| No | 386/1214 (31.8) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 280/1514 (18.5) | 0.51 (0.38–0.68) | 0.47 (0.34–0.64) | |||

Also adjusted for age, ethnic origin, education level, and sexual orientation.

In the preceding 6 months.

CI, confidence interval.

In the multivariate model we found that, independent of sexual setting, men who had more sex partners were more likely to engage in condomless sex. Men who had a steady partner were more likely to use condoms. No significant interaction effects were found in the multivariate model. Alcohol and drug use during sex were not significantly associated with condomless sex and including these variables in the multivariate model did not alter the direction or significance of the effect of sexual setting on condomless sex.

Consistent engagement in group sex

Among 30 men who reported group sex at 4 or more consecutive study visits (total of n=176 visits), a bivariate analysis revealed that condomless sex was more frequently reported during dyadic (38%; 66/175) than during group sex (16%; 28/175), OR=2.88 (95%CI=1.42–5.81).

Association between sexual setting and STI

Men who also had group sex were just as likely to be diagnosed with any STI as men who had dyadic sex only (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariate and multivariate analyses of determinants of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) using logistic regression analysis with generalized estimating equations (GEE) in 2001 sexual reports among 460 MSM attending the STI screening, Amsterdam Cohort Studies, 2009–2012, the Netherlands.

| Proportion of ≥1 STI diagnosis n/N (%) | Bivariate | Multivariate* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | ORadj (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Group sex and dyadic sex versus dyadic sex only** | |||||

| Dyadic sex only | 93/1301 (7.1) | 1 | 0.362 | 1 | 0.519 |

| Group sex and dyadic sex | 60/700 (8.6) | 1.18 (0.83–1.67) | 1.13 (0.70–2.05) | ||

| Anal sex** | |||||

| Condom use/no anal sex | 91/1398 (6.5) | 1 | 0.005 | 1 | 0.019 |

| Condomless anal sex | 62/603 (10.3) | 1.66 (1.17–2.36) | 1.59 (1.08–2.35) | ||

| Number of casual partners** | |||||

| <5 | 33/752 (4.4) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| 5–12 | 55/622 (8.8) | 2.20 (1.38–3.51) | 2.15 (1.28–3.61) | ||

| >12 | 62/605 (10.2) | 2.63 (1.65–4.20) | 3.07 (1.78–5.27) | ||

| Drug use during sex** | |||||

| No | 47/816 (5.8) | 1 | 0.005 | 1 | 0.983 |

| Yes | 101/1099 (9.2) | 1.66 (1.16–2.35) | 0.99 (0.57–1.75) | ||

| Alcohol use during sex** | |||||

| No | 69/982 (7.0) | 1 | 0.275 | 1 | 0.099 |

| Yes | 76/942 (8.1) | 1.20 (0.87–1.66) | 1.74 (0.90–3.37) | ||

| Steady partner** | |||||

| No | 81/902 (9.0) | 1 | 0.008 | 1 | 0.105 |

| Yes | 69/1081 (6.4) | 0.65 (0.47–0.89) | 0.74 (0.52–1.06) | ||

Also adjusted for age, ethnic origin, education level, and sexual orientation.

In the preceding 6 months.

In the multivariate model we found that, independent of sexual setting, men were more likely to be diagnosed with an STI if they had engaged in condomless sex and had a higher number of partners. Men who had a steady partner were less likely to be diagnosed with an STI. No significant interaction effects were found in the multivariate model. Alcohol and drug use were not significantly associated with an STI and including these variables in the multivariate model did not alter the direction or significance of the effect of sexual setting on STI.

Since Gonorrhea and Chlamydia are the most prevalent diagnosed STIs among MSM22 we also examined the influence of sexual setting on diagnosed Gonorrhea (n=74 diagnoses) and Chlamydia (n=84 diagnoses). We found that men who had also engaged in group sex were more likely to be diagnosed with Gonorrhea compared to men who had dyadic sex only (OR=1.71; 95%CI=1.08–2.97), although this effect was not retained in the multivariate model. For Chlamydia we found no significant association with sexual setting.

DISCUSSION

Our results contribute to the existing literature by highlighting the within-person differences in behavior between group sex and dyadic sex among MSM. The findings of this study suggest that MSM report different patterns of risk behavior in the group sex setting than during dyadic sex. MSM who reported both group and dyadic sex reported more condom use in the group sex setting compared to the dyadic sex setting, independent of other factors known to be associated with sexual risk, including number of casual sex partners, alcohol and drug use9,19. Also, among a subsample of men who had frequently engaged in group sex over time, we found, in line with the results described above, that men were more likely to use condoms during group sex than during dyadic sex. Apparently, having frequent group sex experiences did not increase risk behavior within this setting compared to dyadic sex. It could be that, as opposed to group sex, during dyadic sex encounters it is easier for men to discuss issues concerning HIV, considering this setting involves only one-on-one communication. Therefore, men have better opportunities for engaging in HIV risk-reduction strategies, such as serosorting, than during group sex where communication with several different partners might prove much more difficult. This can be an explanation for the higher rates of condom use we found in the group sex setting.

Furthermore, we found that men who had engaged in group sex were significantly older and more likely to have had a steady partner than men who had dyadic sex only. Among the same men who had reported both group and dyadic sex, proportions of drug and alcohol use were lower during group sex encounters than during dyadic sex encounters.

No differences were found for any diagnosed STIs, however, we did find suggestive evidence that men reporting group sex are more likely to be diagnosed with Gonorrhea. It is seemingly contradictive that men are more likely to use condoms during group sex but are at increased risk for Gonorrhea compared to men who only had dyadic casual sex encounters. A possible explanation is that sex techniques other than anal sex, such as fingering, dipping, or toy use and a high partner turnover rate may have also contributed to spreading Gonorrhea among men reporting group sex, which has also been suggested in a previous study10. In the group sex setting, such techniques are more likely to involve infections than during dyadic sex, as STIs such as Gonorrhea can be more readily transmitted from one receptive partner to another by the same person performing these techniques. However, it should be noted we were not able to link STI diagnoses back to a specific partner type or sexual setting, so the STIs we found among men who had reported group sex could also have been acquired during their encounters with dyadic casual partners. Since we found less Gonorrhea diagnoses for men who had dyadic sex only, while having comparable levels of condomless anal sex to men who also had group sex, it is still plausible for men engaging in both sexual settings that STIs were contracted during group sex encounters.

The proportion of men in our study who had engaged in group sex in the preceding six months (37%) was relatively similar to an Australian study23. However, our findings of lower risk behavior during group sex are in contrast with other studies that indicated that MSM participating in group sex are more likely to engage in condomless sex12,13,15,24. Differences could be explained by the fact that these studies also included HIV-positive men who are often found more likely to attend group sex20,25 and are less likely to report condom use during these encounters12,15. Differences could also be explained by the different samples used. These studies specifically recruited participants who had engaged in group sex or are part of an organized group sex network; such networks were found to be associated with MSM having a higher-risk profile17,19,26,27. Our study inclusion was not conditioned to practicing group sex and therefore can reflect a more representative behavioral profile of MSM. Again, differences with previous group sex studies could be the result of a different risk-group profile of the MSM in our cohort and suggest that group sex is not a homogenous risk setting and that risk behavior might depend greatly on the risk profile of the men involved rather then only the setting itself.

Some limitations in this study should be considered. First, as our study sample consisted of highly educated, mainly Western-European MSM, generalization of our findings must be made cautiously. However, data on risk behavior of the cohort have often been similar to larger nation-wide monitoring studies such as the Schorer Monitor28 and therefore have good external validity. Second, we did not collect data on the type of group sex and number of partners per event (e.g., threesome) our participants engaged in, nor on the location (e.g., public versus private venue). These factors have been found to play a role in determining sexual risk behavior during group sex encounters13,29. Also, we did not collect other risk factors that are known to increase risk of HIV and STI during group sex, such as the frequency of partner turnover per event, perceived HIV status of other partners25, mental health issues20, such as depression, and use of other penetrative sexual techniques than anal sex (e.g., toys, fingering, dipping)13,30.

In conclusion, within a cohort of Dutch HIV-negative MSM, this study showed that close to one third of the men engaged in group sex. Our data suggest that during group sex men were more likely to use condoms and use less drugs and alcohol than during dyadic sex. Therefore, group sex might not necessarily be a setting that poses an increased risk for HIV infection compared to dyadic sex, as reported in other studies. However, at the same time, group sex encounters might be higher-risk settings as men reported higher numbers of casual sex partners and have a higher potential for acquiring STIs other than HIV, such as Gonorrhea. Since we had a relatively low number of infections in our sample, more research is needed to affirm these findings. Nevertheless, this apparent discrepancy cannot be ignored and could be explained by the fact that sex techniques other than anal sex contribute to the spread of STIs during group sex encounters. Similar to other studies, our data suggest that group sex encounters should be recognized as a distinct sexual setting which has specific risk and demographic characteristics that need to be addressed accordingly.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funding for the present study was provided by the AIDS Fonds (project number 2008025). Dr. Sandfort’s contribution was supported by NIMH Center Grant P30-MH43520.

The authors wish to thank the participants of the Amsterdam Cohort Studies for their contribution, research nurses of the ACS Marc van Wijk and Marjolein Martens for data collection and cohort management, Gerben Rienk Visser for data management, Ronald Geskus for critically reading the manuscript, and Claire Buswell for editing the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Wijnand van den Boom and José Heuker analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the draft manuscript. Femke Lambers, Maria Prins, and Theo Sandfort provided substantial contributions to the analyses and interpretation of the data. Udi Davidovich and Ineke Stolte designed and supervised the overall study and contributed to the analyses and interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to subsequent drafts and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe. HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2013. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) Sexually transmitted infections in Europe 2011. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2012. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savage EJ, Hughes G, Ison C, et al. Syphilis and gonorrhoea in men who have sex with men: a European overview. Euro Surveill. 2009:14. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.47.19417-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Bij AK, Stolte IG, Coutinho RA, et al. Increase of sexually transmitted infections, but not HIV, among young homosexual men in Amsterdam: are STIs still reliable markers for HIV transmission? Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:34–37. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.007997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcus U, Bremer V, Hamouda O, et al. Understanding recent increases in the incidence of sexually transmitted infections in men having sex with men: changes in risk behavior from risk avoidance to risk reduction. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:11–17. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187224.10428.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snowden JM, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Prevalence of seroadaptive behaviours of men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2004. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:469–476. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolte IG, Coutinho RA. Risk behaviour and sexually transmitted diseases are on the rise in gay men, but what is happening with HIV? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2002;15:37–41. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen IA, Geskus RB, Davidovich U, et al. Ongoing HIV-1 transmission among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam: a 25-year prospective cohort study. AIDS. 2011;25:493–501. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328342fbe9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin F, Prestage GP, Mao L, et al. Incidence and risk factors for urethral and anal gonorrhoea and chlamydia in a cohort of HIV-negative homosexual men: the Health in Men Study. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:113–119. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.021915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vallabhaneni S, Li X, Vittinghoff E, et al. Seroadaptive practices: association with HIV acquisition among HIV-negative men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prestage GP, Hudson J, Down I, et al. Gay men who engage in group sex are at increased risk of HIV infection and onward transmission. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:724–730. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grov C, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, et al. HIV risk in group sexual encounters: an event-level analysis from a national online survey of MSM in the U. S J Sex Med. 2013;10:2285–2294. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Bland SE, et al. Sex parties among urban MSM: an emerging culture and HIV risk environment. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:305–318. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips G, Magnus M, Kuo I, et al. Correlates of Group Sex Among a Community-Based Sample of Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM) in Washington, DC. AIDS Behav. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prestage GP, Hudson J, Jin F, et al. Testing for HIV and sexually transmissible infections within a mainly online sample of gay men who engage in group sex. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:70–74. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Bland S, et al. “It’s a quick way to get what you want”: a formative exploration of HIV risk among urban Massachusetts men who have sex with men who attend sex parties. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:659–674. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberger JG, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Sexual behaviors and situational characteristics of most recent male-partnered sexual event among gay and bisexually identified men in the United States. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3040–3050. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prestage G, Grierson J, Bradley J, et al. The role of drugs during group sex among gay men in Australia. Sex Health. 2009;6:310–317. doi: 10.1071/SH09014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirshfield S, Schrimshaw EW, Stall RD, et al. Drug Use, Sexual Risk, and Syndemic Production Among Men Who Have Sex With Men Who Engage in Group Sexual Encounters. Am J Public Health. 2015:e1–e10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Griensven GJ, de Vroome EM, Goudsmit J, et al. Changes in sexual behaviour and the fall in incidence of HIV infection among homosexual men. BMJ. 1989;298:218–221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6668.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.STI clinic Amsterdam. Annual report STI clinic Amsterdam 2013 (in Dutch, summary in English) 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prestage G, Down I, Grulich A, et al. Sex partying among gay men in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, Australia. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:298–304. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9824-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grov C, Rendina HJ, Breslow AS, et al. Characteristics of men who have sex with men (MSM) who attend sex parties: results from a national online sample in the USA. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:26–32. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT. HIV status differences in venues where highly sexually active gay and bisexual men meet sex partners: results from a pilot study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22:496–508. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.6.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green AI, Halkitis PN. Crystal methamphetamine and sexual sociality in an urban gay subculture: an elective affinity. Cult Health Sex. 2006;8:317–333. doi: 10.1080/13691050600783320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sowell RL, Lindsey C, Spicer T. Group sex in gay men: its meaning and HIV prevention implications. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 1998;9:59–71. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(98)80020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Empelen P, Van Berkel M, Roos E, et al. Schorer Monitor. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reisen CA, Iracheta MA, Zea MC, et al. Sex in public and private settings among Latino MSM. AIDS Care. 2010;22:697–704. doi: 10.1080/09540120903325433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin F, Crawford J, Prestage GP, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse, risk reduction behaviours, and subsequent HIV infection in a cohort of homosexual men. AIDS. 2009;23:243–252. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831fb51a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]