Abstract

Objectives

Girls’ rates of drug use have met up with, and in some instances, surpassed boys’ use. Though girls and boys share risk and protective factors associated with drug use, girls also have gender-specific risks. Interventions to prevent girls’ drug use must be tailored to address the dynamics of female adolescence.

Methods

One such intervention, called RealTeen, is a 9-session, web-based drug abuse prevention program designed to address such gender-specific risk factors associated with young girls’ drug use as depressed mood, low self-esteem, and high levels of perceived stress as well as general drug use risk factors of peer and social influences. Web-based delivery enables girls to interact with the program at their own pace and in a location of their choosing.

Implications

This paper describes the processes and challenges associated with developing and programming a gender-specific, web-based intervention to prevent drug use among adolescent girls.

Keywords: web-based, gender-specific, adolescent, prevention, drug use

Introduction

Adolescent Drug Use

The costs and consequences of adolescent drug use are significant, well-established, and all too familiar to social work practice (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2014; National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2003; Townsend, Flisher, & King, 2007). Relative to their abstaining peers, drug-using youths are more likely to experience physical and mental health issues, accidents and injuries, physical altercations, risky sexual behaviors, truancy, poorer academic performance, unintended pregnancy and suicide. Furthermore, the earlier youths initiate drug use, the more likely they are to experience problems with addiction as adults (Grant & Dawson, 1998; Hingson, Heeren, & Winter, 2006). Preventive interventions that are theory-based, tested, and easy to disseminate are clearly called for to stem drug use among adolescents.

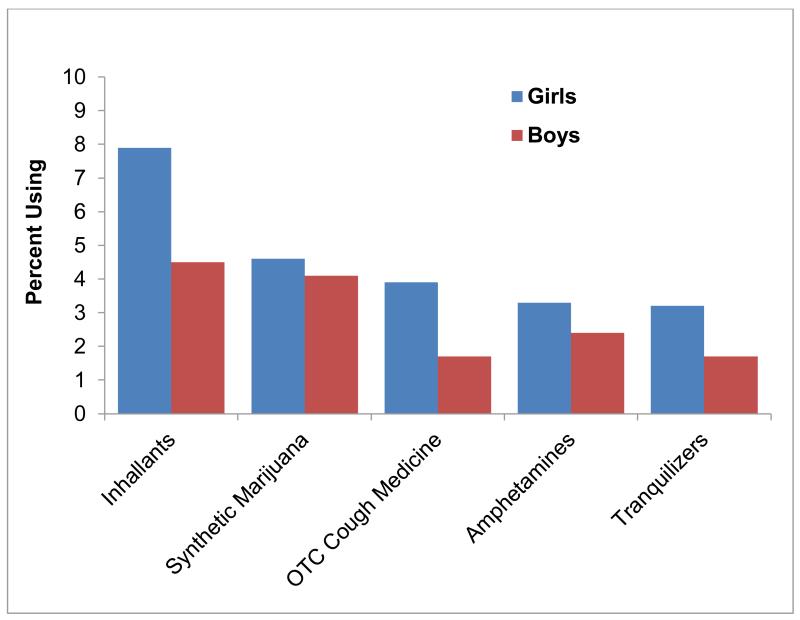

Though the rates of adolescent drug use in the last decade have remained relatively stable and are positive relative to prior decades, the transition from middle to high school continues to witness dramatic increases in substance use rates (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2014). Whereas 8.5% of eighth graders report past-month drug use, their tenth- and twelfth-grade counterparts report rates of 19.4% and 25.5%, respectively. Furthermore, the long-standing gender gap in rates of use has continued to shrink such that girls’ drug use often meets and in some cases surpasses boys’ use (Fig. 1; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2013). Therefore, girls’ patterns of use, in combination with the personal and societal consequences of later drug use and addiction, argue for a gender-specific program targeted to girls in middle school.

Figure 1.

Past-Year Drug Use among Eighth Graders.

Risk Factors for Girls’ Drug Use

Not surprisingly, girls and boys share common paths to drug use. Chief among these are peer influences (Newcomb & Bentler, 1989; Sales, Sambrano, Springer, & Turner, 2003). Positive attitudes toward, and erroneous beliefs about, drug use are also risk factors for boys and girls alike (Newcomb, Maddahian, & Bentler, 1986). Yet gender differences moderate drug use. Girls’ risk for drug use is related to their increased risk for low self-esteem, increased levels of stress, and higher rates of depression, relative to their male counterparts (Kumpfer, Smith, & Summerhays, 2008). Compared to girls with high self-esteem, young girls with low self-esteem are more likely to engage in heavy alcohol consumption as they progress through adolescence (Kumpulainen & Roine, 2002). Girls are twice as likely as boys to experience high levels of stress—a known risk factor for drug use (Baer, Garmezy, McLaughlin, Pokorny, & Wernick, 1987; Sanders-Phillips, 1998). Around puberty, girls are also vulnerable to depressed mood, another risk factor for drug use (Silberg, Rutter, D’Onofrio, & Eaves, 2003; Wiesner & Ittel, 2002). In fact, girls who engage even in light to moderate drug use are more likely to report depressive symptoms, whereas boys are not (Hallfors et al., 2004).

Unfortunately, girls’ differential risks for drug use do not abate with the end of adolescence. As adults, drug-using women are more sensitive to the adverse short- and long-term health effects of drugs than men (Fernández-Solà et al., 1997; Jarque-Lopez et al., 2001). Once addicted, women have more trouble than men quitting a variety of drugs, including but not limited to nicotine and alcohol (Roth, Cosgrove, & Carroll, 2004). Social work interventionists can lead the field in developing and testing programs tailored expressly for adolescent girls to prevent the onset of drug use.

Existing Interventions

A number of gender-specific interventions to prevent drug use among girls have been developed, tested, and found to have modest salubrious effects (Elliot et al., 2006; Weiss & Nicholson, 1998). Traditional interventions delivered didactically in live-group settings, however, are often limited in reach and effect. In large part, these programs are burdened by insufficient staff training, time limitations, budgetary issues, and space constraints—the latter particularly an issue when providers wish to deliver tailored interventions to a subgroup (e.g., programming for teen girls).

Web-based technologies hold promise for social work practice to increase the reach and efficacy of tailored interventions. These interventions can provide schools, community-based agencies, health clinics, and other providers access to interventions that require little to no staff training, allowing for time- and cost-savings. Web-based delivery also offers practitioners the opportunity to provide high-fidelity and tailored interventions to the populations they serve. Perhaps most compelling, web-based interventions serve youth where they spend much of their time, engaging in a format they enjoy. This paper details the development and tailoring process of a web-based, drug abuse prevention program, called RealTeen. Though specific to adolescent girls and drug use, the paper aims to provide a framework for social work practitioners to develop and tailor intervention programs irrespective of the social problem or designated population.

Method: The Story behind the Intervention

The Intervention

RealTeen is a gender-specific, web-based drug abuse prevention intervention for girls. The primary goal of the program is to address 13- & 14-year-old girls’ drug use risk factors to delay onset and reduce overall rates of use. The program aims to achieve this goal by improving girls’ cognitive- and social-skills around such areas as coping with stress, managing mood, communicating assertively, and maintaining a healthy body image. Therefore, the program intends not only to reduce girls’ drug use, but also to improve their overall well-being.

RealTeen resulted from a culmination of epidemiological data, theory, evidenced-based practices, and prior experience with intervention development and testing. Because the intervention is delivered online, the program is designed to engage girls from diverse socio-economic, ethnic, racial, and geographic backgrounds. The intervention consists of nine sessions: goal setting, decision making, puberty, body image, coping, drug knowledge, communication and assertiveness, and a review (see Table 1 for a description of each session). The review session provides an opportunity for girls to witness how positive regard for self, care for one’s body, and effective communication work reciprocally to help maintain goals, make healthy decisions, manage mood, and cope with stress.

Table 1. Summary of RealTeen Intervention Content.

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction & Goal Setting |

Acquaint girls with website features and customize homepage settings; Review steps to short- and long-term goal setting to achieve aspirations and stay healthy and safe; Generate goals and immediate actions steps for each goal |

| 2. Decision Making |

Practice a 5-step problem-solving sequence to meet goals and manage difficult situations; Understand that there is more than one option in any situation; Apply skills to various scenarios, including drug and alcohol use offers |

| 3. Puberty | Review physical, mental, and emotional changes associated with puberty; Recognize what changes are normal and unavoidable; Practice positive self-talk to boost confidence by generating a list of things they like about themselves |

| 4. Body Image | Learn how media and social influences affect body image and self-esteem; Distinguish between healthy and unhealthy strategies to improve self-esteem and body image; Analyze various media advertisement |

| 5. Coping with Stress |

Identify sources and symptoms of stress and healthy coping strategies; Explore the connection between behavior and mood by reframing events; Expose myths about drug use and stress relief; Learn healthy coping methods |

| 6. Drug Knowledge |

Learn about the prevalence of peer drug use; Understand the direct and indirect influences of substance use; Explore the short- and long-term consequences of drug use; Learn that drug use is a counterproductive coping skill |

| 7. & 8. Communication |

Distinguish between assertive, aggressive, and passive communication; Learn about verbal and non-verbal communication; Practice scenarios to manage conflict, reduce stress, increase refusal self-efficacy and self- esteem |

| 9. Review | Review each of the skills-based sessions; Understand how skills build on and are interdependent with one another; Practice their newly acquired skills by engaging in scenarios of drug use opportunity and refusal |

The RealTeen website is accessible through any internet browser, but runs optimally on a laptop or desktop computer. The nine sessions housed on the website each require approximately 15-20 minutes; sessions are completed once a week. Each skills-based session focuses on a different topic, yet such key concepts as decision making and self-esteem appear repeatedly to reinforce learning and to provide continuity. Further continuity is achieved by structuring each session similarly, beginning with a skills-based lesson, followed by interactive exercises to enhance skills acquisition, and ending with a review and short quiz.

The interactive exercises employed to enhance skills acquisition often require girls to generate a response to a hypothetical, yet realistic scenario. For example, in a session on communication, girls must generate a response to an offer to smoke pot from a friend’s older brother. Once entered online, girls then have the option to keep their response private or to make it public. Private responses are stored in girls’ online journals that only they can access. Public responses post to the social feed for that particular session. The social feed appears on the homepage and can be accessed any time. By clicking on the feed for a particular session, girls can view every publically posted response in chronological order. The social feed creates a sense of community and promotes self-reflection while protecting anonymity as posts are identified only by a self-selected icon (e.g., a star, a ballet shoe, a soccer ball).

Theory and Rationale

The intervention content is based on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986; Flay, Snyder, & Petraitis, 2009) and a resiliency framework (Masten & Powell, 2003) to address girls’ general risk factors as well as their gender-specific risk factors, respectively. Following social cognitive theory, the intervention aims to reduce girls’ risks of peer and social influences by increasing their cognitive-behavioral skills through personal and social skills-based sessions. Referred to as comprehensive skills training programs, these interventions are among the most effective practices to teach youths to resist peer and social influences (Tobler et al., 2000). By using a resiliency framework, the intervention content addresses girls’ gender-specific risks of low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and stress (Rew & Horner, 2003). Essential characteristics of resiliency include competency at communicating, problem-solving, and managing stress (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). Therefore, in addition to increasing girls’ personal and social skills around general peer and social influences, session content enhances girls’ intrapersonal competencies to hold a positive self-image, manage negative moods, and cope with frequent stress.

Tailoring an Intervention for Gender Specificity

Once the specific skills that the intervention would address were established, the focus shifted to tailoring features of the intervention that would maximize appeal to our adolescent female audience. Cognizant of first impressions and the ease with which a browser can be closed, the homepage needed to convey gender-specificity. The session narrator would have to be visually appealing, cool, yet credible. The language used by the narrator and ancillary characters would have to resonate with the audience. Therefore, our gender-specific tailoring focused on: 1) the website that would house the nine intervention sessions, 2) the narrator who would deliver the learning material, and 3) the nature of the content within each session.

The RealTeen Website

The motivation for the website was to create a space girls would visit even if they do not have a session to complete. As such, the website homepage includes features appealing to adolescent girls including: feeds from the latest entertainment sites, online polls, horoscopes, beauty tips, and a quote of the day. A vertical menu bar on the far right of the page provides the links to each of the nine sessions. The site is simple to navigate and employs youthful, feminine colors and graphics. Exploiting girls’ desired autonomy, the website includes customizable features. Girls can change the background of their homepages by choosing one of four different wallpapers (named “Girly Glam,” “Earthly Elegant,” “Rockin’ Retro,” “Classic Chic”). Girls can also select, from a list of 40 icons, a symbol to represents their posts to the social feed (e.g., a star, a ballet shoe, a soccer ball). These modest customizable features allow girls to personalize their homepage and potentially enhance the user experience.

The RealTeen Narrator

Each of the nine sessions is guided by a narrator, named Alexis. Because positive, peer modeling is associated with effective intervention efforts (Gottfredson & Wilson, 2003; Yancey, Siegel, & McDaniel, 2002), she is portrayed as a credible, attractive, older peer. Somewhere in her late teens or early twenties, Alexis evokes a sympathetic and supportive persona. She discusses session topics with authority and experience. As a positive peer model, Alexis displays confidence, assertive communication, and engages careful in thought. Aware that skills acquisition are enhanced when learners perceive commonalities with a role model (Bandura, 1977, 1986), the challenge was to create a single narrator who could connect to an audience that shares only gender, age, and language spoken in common.

Ideally, a web-based program would allow users to tailor their narrator (e.g., select a hair style, skin tone, attire). Commercial gaming products typically make such provisions. An educational, web-based program for the social sciences, however, has a limited budget. Creating a single narrator with mass appeal required finesse. Before settling on her final image, iterations of Alexis were deemed “too white” or “too nerdy” or “too urban” to have necessary mass appeal. Ultimately, our program developers captured a young woman who is ethnically and racially ambiguous with dark purple hair and light brown skin (Figure 2.). Her face, with large cartoonish eyes, frequently appears close-up to convey emotion and evince a desire to speak directly to the listener. Assuming that most young female users interact with session content in their bedroom, Alexis appears in her room, too. This shared intimate setting serves to connect the female audience to Alexis and increase the sense of commonality to enhance learning.

Figure 2.

Intervention Narrator.

The RealTeen Session Content

A single-gender audience affords the opportunity to discuss topics and provide examples that are female-centric. For instance, boys and girls alike deal with pressures from peers and society. Yet the pressures girls experience from their female peers and the images they see from media are decidedly different from the pressures boys have from peers and media. Therefore, content on how to critically analyze media images uses examples of retouched female bodies and alcohol and cigarette ads that target young women. In the coping with stress session, for instance, gender-neutral methods like proper nutrition, adequate sleep, and exercise are discussed. But activities that might resonate less with boys like journaling, talking on the phone to a friend, yoga, and dance are also suggested. The session content on pubertal changes addresses concerns salient to girls (e.g, weight gain, acne, menses) in a way that would prove challenging if it were delivered to girls and boys.

Though Alexis as the RealTeen narrator provides the learning material, each session builds off of a dialogue between Alexis and a character named Tori. Tori—also an animated character—is a 13-year-old girl who serves as a proxy for the audience members. As Alexis presents information with authority and ease, Tori typically challenges her with questions and counterpoints. For instance, in the decision-making session, Alexis describes how the first step in effective decision making is to stop and think about one’s options. Tori counters that she is often too busy to stop and laments that sometimes she only has one option. Alexis uses active listening, affirms that Tori’s feelings are typical and frustrating, and encourages her to continue practicing the process. In this way, the learning material is presented and the typical questions or doubts the target audience may generate are addressed.

Ensuring that the language and examples employed throughout the session content would appeal to a broad audience of girls was perhaps most difficult. Though specifying location, setting, and characters increases plausibility, doing so also raises the specter of alienating girls for whom the scenario does not apply. For instance, when Tori describes a typical stressful situation to solicit Alexis’s help, does the scenario relate to academics, a lack of friends, physical insecurities? What are the potential implications for how Tori is perceived by the audience depending on which stressor she describes? Even benign choices such as whether to use the term “pot,” “a joint,” “weed,” or “marijuana” require attention. Awareness of whether terms are dated, geographically specific, or ubiquitous in the adolescent female lexicon is vital to delivering engaging material. When faced with dilemmas around session content, the solution was guided not by an attempt to appeal to everyone, but to make it general enough to alienate the fewest.

Discussion

Intervention research is vital to advancing the social work profession and to ameliorating the behavioral and social problems that affect those whom the profession serves (Boruch, De Moya, & Snyder, 2002; Soydan, 2008). Effective intervention development requires careful assessment of prevalence data, attention to risk and protective factors, and a theoretical foundation. This paper, though focused on a web-based, drug abuse prevention program, provides a framework for developing interventions, irrespective of the problem addressed or population served.

Not all interventions are best suited for online delivery. The advantages of online delivery, however, are many (Webb, Joseph, Yardley, & Michie, 2010; Portnoy, Scott-Sheldon, Johnson, & Carey, 2008). If effective, our intervention can easily be disseminated across the country with fidelity, at no cost to schools or communities, and with no staff time or training required. Online program delivery, like traditional program delivery, is not without challenges. Chief among them is settling on answers to such questions as “What do we convey?” “To whom?” and “How will the message be received?” A computerized intervention cannot respond to ad hoc questions like a teacher or practitioner does. Therefore, anticipating the target audience’s responses to the programmed material requires time, skill, and consideration.

RealTeen employs hypothetical scenarios to provide a context for the learning material and for girls to practice skills acquisition. Determining the nature of those scenarios was challenging. Use the wrong word to describe a drug, present the protagonist as too low on the social pecking order, or place a scenario in a setting that is exclusive to a certain group (e.g., urban, rural, suburban) and the program can be perceived irrelevant. All interventions, regardless of importance or efficacy, are subject to dismissal if the audience does not find the material pertinent and engaging (Kreps & Neuhauser, 2010).

Interventions must be built with care and attention to the target audience. RealTeen was crafted for teenage girls from across the country, regardless of race, class, or geography. Admittedly, in trying to reach too broadly, a program will not resonate for all girls. Nevertheless, a web-based prevention program would be a disservice to itself, to the field, and to the larger goal of reducing adolescent drug use, if the target audience is too narrow.

Even the most effective and well-crafted interventions are futile if the intended audience does not receive the material. Few would argue that engaging with drug abuse prevention program content ranks high on girls’ lists of things to do online, or otherwise. Like adults, adolescents are finicky consumers, even of online material. Adolescents, however, are eager to engage and learn when they perceive that the material is relevant. As intervention scientists, we must develop effective programs that are not only theory- and evidence-based, but that also capture and maintain the attention of the audience.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, grant number: R01DA031782.

References

- Baer PE, Garmezy LB, McLaughlin RJ, Pokorny AD, Wernick MJ. Stress, coping, family conflict, and adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1987;10(5):449–466. doi: 10.1007/BF00846144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice Hall; Englwood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boruch R, De Moya D, Snyder B. The importance of randomized field trials in education and related areas. In: Mosteller F, Boruch R, editors. Evidence matters: Randomized trials in education research. Brookings Institute Press; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 50–79. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DL, Moe EL, Goldberg L, DeFrancesco CA, Durham MB, Hix-Small H. Definition and outcome of a curriculum to prevent disordered eating and body-shaping drug use. Journal of School Health. 2006;76(2):67–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00070.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Solà M, Estruch M, Nicolás M, Paré M, Sacanella M, Antúnez M, Urbano-Márquez M. Comparison of alcoholic cardiomyopathy in women versus men. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1997;80(4):481–485. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Snyder F, Petraitis J. The theory of triadic influence. In: DiClemente RJ, Kegler MC, Crosby RA, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. 2nd ed Jossey-Bass; New York: 2009. pp. 451–510. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Wilson DB. Characteristics of effective school-based substance abuse prevention. Prevention Science. 2003;4(1):27–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1021782710278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10(2):163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(3):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160(7):739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarque-Lopez A, Gonzalez-Reimers E, Rodriguez-Moreno F, Santolaria-Fernandez F, Lopez-Lirola A, Ros-Vilamajo R, Martinez-Riera A. Prevalence and mortality of heavy drinkers in a general medical hospital unit. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2001;36(4):335–338. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on drug use: 2012 Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National results on drug use: 1975-2013: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Smith P, Summerhays JF. A wakeup call to the prevention field: Are prevention programs for substance use effective for girls? Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43(8-9):978–1001. doi: 10.1080/10826080801914261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen K, Roine S. Depressive symptoms at the age of 12 years and future heavy alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(3):425–436. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreps GL, Neuhauser L. New directions in eHealth communication: opportunities and challenges. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;78(3):329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Powell JL, Luthar SS. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2003. A resilience framework for research, policy, and practice; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University . The formative years: Pathways to substance abuse among girls and young women ages 8-22. Author; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Substance use and abuse among children and teenagers. American Psychologist. 1989;44(2):242–248. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Maddahian E, Bentler PM. Risk factors for drug use among adolescents: Concurrent and longitudinal analyses. American Journal of Public Health. 1986;76(5):525–531. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.5.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy Consequences of illicit drug use in America. 2014 Apr; Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/Fact_Sheets/consequences_of_illicit_drug_use_-_fact_sheet_april_2014.pdf.

- Portnoy DB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Johnson BT, Carey MP. Computer-delivered interventions for health promotion and behavioral risk reduction: A meta-analysis of 75 randomized controlled trials, 1988-2007. Preventive Medicine. 2008;47:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rew L, Horner SD. Youth resilience framework for reducing health-risk behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2003;18(6):379–388. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(03)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth ME, Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the vulnerability to drug abuse: a review of preclinical studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28(6):533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales E, Sambrano S, Springer FJ, Turner C. Risk, protection, and substance use in adolescents: A multisite model. Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33(1):91–105. doi: 10.2190/LFJ0-ER64-1FVY-PA7L. doi: 10.2190/LFJ0-ER64-1FVY-PA7L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K. Factors influencing health behaviors and drug abuse among low-income Black and Latino women. In: Wetherington CL, Roman AB, editors. Drug addiction research and the health of women. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1998. pp. 439–466. [Google Scholar]

- Silberg J, Rutter M, D’Onofrio B, Eaves L. Genetic and environmental risk factors in adolescent substance use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(5):664–676. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soydan H. Producing knowledge for evidence-based practice and the future of social work research. In: Bryderup IM, editor. Evidenced based and knowledge based social work: Research methods and approaches in social work research. Aarhus University Press; 2008. pp. 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler NS, Roona MR, Ochshorn P, Marshall DG, Streke AV, Stackpole KM. School-based adolescent drug prevention programs: 1998 meta-analysis. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;20(4):275–336. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend L, Flisher AJ, King G. A systematic review of the relationship between high school dropout and substance use. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10(4):295–317. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb T, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2010;12(1):e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss FL, Nicholson HJ. Friendly PEERsuasionSM against substance use: The Girls IncorporatedSM model and evaluation. Drugs & Society. 1998;12(1-2):7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner M, Ittel A. Relations of pubertal timing and depressive symptoms to substance use in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2002;22(1):5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Siegel JM, McDaniel KL. Role models, ethnic identity, and health-risk behaviors in urban adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(1):55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]