Abstract

Rumination and worry, two forms of perseverative thinking, hold promise as core processes that transect depressive and anxiety disorders. Whereas previous studies have been limited to the laboratory or to single diagnoses, we used experience sampling methods to assess and validate rumination and worry as transdiagnostic phenomena in the daily lives of individuals diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), and co-occurring MDD-GAD. Clinical and healthy control participants carried a hand-held electronic device for one week. Eight times per day they reported on their current levels of rumination and worry and their theoretically postulated features: thought unpleasantness, repetitiveness, abstractness, uncontrollability, temporal orientation, and content, and overall senses of certainty and control. Both rumination and worry emerged as transdiagnostic processes that cut across MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD. Furthermore, most psychological theories concerning rumination and worry strongly mapped onto participants’ reports, providing the first naturalistic validation of these constructs.

Keywords: rumination, worry, experience sampling method, Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, transdiagnostic

Like virtually all psychological phenomena, rumination and worry have been investigated primarily in the laboratory, through self-report measures, experimental paradigms and, more recently, neuroimaging methods (e.g., Borkovec & Inz, 1990; Cooney, Joormann, Eugène, Dennis, & Gotlib, 2010; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1993; Paulesu et al., 2010). Rumination refers broadly to perseverative thinking focused on one’s negative feelings and problems (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) and, traditionally, has been examined as a risk factor for and associated feature of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008). Worry, in contrast, refers to perseverative thinking focused on sources of potential threat (Borkovec, Robinson, Pruzinsky, & DePree, 1983) and is a defining symptom of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Importantly, however, a growing literature suggests that these two constructs are transdiagnostic, representing specific forms of the overarching process of perseverative thought that correlates with both depressive and anxiety symptoms (Ruscio, Seitchik, Gentes, Jones, & Hallion, 2011; Segerstrom, Tsao, Alden, & Craske, 2000; Yook, Kim, Suh, & Lee, 2010). In a transdiagnostic framework, rumination and worry are theorized to share key qualities of unpleasantness, repetitiveness, abstractness, and uncontrollability of thinking (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004). As we review below, theorists have also postulated unique characteristics of these two constructs (e.g., Borkovec, Alcaine, & Behar, 2004, Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). While perspectives on the common and distinct features of rumination and worry are not necessarily inconsistent with one another, these theories were developed through separate lines of research and are just beginning to be tested in a more integrative manner in the laboratory. Are psychological theories developed in the laboratory consistent with the naturalistic experiences of rumination and worry? Experience sampling methodology (ESM) uniquely enables us to answer this question (Myin-Germeys et al., 2009). In this study, we used ESM to test, for the first time, theories of rumination and worry and validate these as transdiagnostic constructs in the daily lives of individuals with MDD, GAD, and co-occurring MDD-GAD.

Most contemporary conceptualizations of rumination originate from Nolen-Hoeksema’s response styles theory (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), in which rumination is formulated as “a mode of responding to distress that involves repetitively and passively focusing on symptoms of distress and the possible causes and consequences of these symptoms” (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008, p. 400). Theorists generally agree that the core content of ruminative thought includes a focus on the self and a temporal orientation toward past events and experiences (e.g., “Why did I react that way?”, “Why me?”) (reviewed in Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008, Papageorgiou, 2006, and Thomsen, 2006). In addition, drawing on the work of Lyubomirsky and colleagues (1999), Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (2008) proposed that rumination involves an overall sense of certainty that situations in one’s life are uncontrollable; these impressions of certainty and lack of control are posited to support the non-conscious function of rumination to avert the need to take responsibility in response to aversive situations.

Alongside the theoretical development of rumination, the concept of worry emerged largely from the work of Borkovec and colleagues as “a chain of thoughts and images, negatively affect-laden and relatively uncontrollable. The worry process represents an attempt to engage in mental problem-solving on an issue whose outcome is uncertain but contains the possibility of one or more negative outcomes” (Borkovec, Robinson, Pruzinsky, & DuPree, 1983, p. 10). Therefore, in contrast to rumination, worry is defined by a temporal orientation toward the future (e.g., “What if [negative event] were to happen?”). A predominance of verbal or linguistic activity is also theorized to be a central feature of worry; indeed, this characteristic is thought to support the non-conscious function of worry to cognitively avoid aversive images (reviewed in Borkovec et al., 2004). Finally, in synthesizing distinctions between worry and rumination suggested elsewhere (e.g., Alloy, Kelly, Mineka, & Clements, 1990), Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (2008) argued that worry involves a sense of uncertainty rather than certainty about situations, and a belief that situations might be controllable if one were to work hard (or worry) enough.

Given the role of laboratory findings in the development of theories of rumination and worry, it is not surprising that these postulates have already received some empirical support. Most laboratory studies have focused on a subset of features of these processes. For example, the distinct temporal orientations of rumination and worry have been documented in studies with nonclinical samples in which participants rated the temporal focus of questionnaire items assessing these constructs (Watkins, Moulds, & Mackintosh, 2005) and in which participants reported the temporal focus of their thoughts while undergoing rumination and worry inductions (McLaughlin, Borkovec, & Sibrava, 2007). Other studies have used cognitive inductions and thought sampling procedures in order to demonstrate that rumination is associated with a low sense of control over situations (Lyubomirsky et al., 1999) and that worry is associated with verbal-linguistic mental activity (Borkovec & Inz, 1990). In a rare daily diary study, Papageorgiou and Wells (1999) asked a sample of nonclinical participants to record their first two naturally-occurring depressive and anxious thoughts over the course of two weeks; among several findings, these researchers found that depressive thoughts were significantly past-oriented and anxious thoughts were significantly verbal-linguistic.

To date, researchers have used ESM with nonclinical samples in order to examine the relations of rumination to depressive symptoms (Pasyugina, Koval, De Leersnyder, Mesquita, & Kuppens, in press; Pillai, Steenburg, Ciesla, Roth, & Drake, 2014), negative affect (Moberly & Watkins, 2008), and goal pursuit (Moberly & Watkins, 2010). In addition, investigators have used ESM to document the occurrence of rumination and worry in psychosis (Hartley, Haddock, Vasconcelos E Sa, Emsley, & Barrowclough, 2014). Importantly, however, ESM has never before been utilized to test the very definitions of rumination and worry, which is critical not only in advancing basic scientific knowledge concerning these constructs, but also in developing and testing interventions for these maladaptive processes. In this context, it is noteworthy that the canonical self-report measures of rumination and worry, the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS; Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003) and Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990), respectively, assume these postulated features (e.g., repetitiveness, uncontrollability) rather than directly assessing the relevance of these features to the overall constructs. Furthermore, self-report questionnaires are limited by the potential for biases in retrospection, which is of particular concern when studying emotional disorders (reviewed in Kircanski, Joormann, & Gotlib, 2012, and Mathews & MacLeod, 2005). While experimental paradigms afford the opportunity to examine thought processes in real time, this advantage comes at the expense of reduced ecological validity. Addressing these limitations, ESM enables both the naturalistic and real-time assessment of individuals’ thought processes.

The present study was designed to bridge two gaps in the clinical literature: first, to test theories of rumination and worry in a novel ecologically valid manner; and second, to validate these constructs as transdiagnostic phenomena that cut across MDD, GAD, and co-occurring MDD-GAD. We hypothesized that, in daily life, participants diagnosed with MDD, GAD, and co-occurring MDD-GAD all would report significantly higher levels of rumination and worry than would control participants with no history of psychiatric disorder (CTL). We also hypothesized that participants’ naturalistic reports of rumination and worry would strongly map onto theories of these constructs. That is, we expected to find evidence for both the theorized common features (unpleasantness, repetitiveness, abstractness, uncontrollability) and distinct features (temporal orientation, content focus, sense of certainty/uncertainty, and sense of control/lack of control) of rumination and worry.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were adult women between the ages of 18 and 50 years. We restricted our sample to women both to strengthen statistical power and because MDD, GAD, and their co-occurrence are approximately twice as prevalent in women as in men (Kendler, Gardner, Gatz, & Pedersen, 2007). Participants were recruited through online advertisements and local psychiatric clinics, and were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria through a telephone interview. Exclusion criteria were: not fluent in English; history of learning disabilities, severe head trauma, psychotic symptoms, or bipolar disorder; and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994)-defined alcohol or substance abuse in the past six months. Individuals who were identified as likely to meet study inclusion criteria were invited to participate in a diagnostic evaluation in the laboratory based on DSM-IV-TR criteria using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) that was administered by a highly-trained interviewer. Participants in the MDD group (n = 16) met diagnostic criteria for current MDD, with no diagnosis of GAD currently or within the past 24 months. Similarly, participants in the GAD group (n = 15) met diagnostic criteria for current GAD, with no diagnosis of MDD currently or within the past 24 months. Given previous findings that persons with one-year or recent comorbidity of MDD and GAD function similarly to those with currently co-occurring MDD-GAD (e.g., Kessler, DuPont, Berglund, & Wittchen, 1999), we excluded potential participants from the MDD group and the GAD group if they had the other disorder within the past 24 months in order to strengthen the potential to find any group differences. Participants in the co-occurring MDD-GAD group (n = 20) met diagnostic criteria for current MDD and current GAD. DSM-IV lists a hierarchical exclusion criterion for GAD when caseness for this disorder is met only in the context of MDD; however, given that the epidemiological and clinical literature and a recent report from the DSM-5 work group indicate little utility and, moreover, significant problems associated with this hierarchical exclusion criterion (e.g., Andrews et al., 2010; Lawrence, Liverant, Rosellini, & Brown, 2009), we did not impose the hierarchy rule in order to capture this important and understudied co-occurring MDD-GAD group. Finally, participants in the CTL group (n = 19) did not meet criteria for any current or lifetime Axis I disorder. Inter-rater reliability is excellent among the laboratory interviewers for depressive and anxiety diagnoses (κ = .92 to 1.0).

Following the diagnostic evaluation, participants returned to the laboratory to complete a set of self-report questionnaires and tasks. Participants received a hand-held electronic device (Palm Pilot Z22) and completed comprehensive training in the use of the device and ESM items as well as a practice trial in the laboratory with experimenter feedback. Participants were also given take-home instructions that reinforced the definitions of the ESM items. The Palm units were individually programmed using ESP 4.0 software (Barrett & Feldman-Barrett, 2000) to prompt participants eight times per day during a 12-hour period between 8 a.m. and 10 p.m. (based on participants’ waking times and bedtimes) for seven to eight consecutive days. Prompts occurred at randomized times within 90-minute intervals (M = 96 minutes, SD = 37 minutes). Participants were given five minutes to respond to each prompt; otherwise, data for the prompt was recorded as missing. Participants received additional compensation if they responded to at least 90% of the prompts. Following the procedures of previous ESM studies, we excluded from the dataset one participant who did not respond to at least five prompts (e.g., Bylsma, Taylor-Clift, & Rottenberg, 2011). The ESM protocol was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

ESM Measures

Rumination and Worry

At each prompt, participants reported their current levels of rumination and worry using two separate items with 100-point visual analog scales (1 = not at all, 100 = very much so). Item content was drawn from previous ESM studies of rumination and worry (e.g., Hartley et al., 2014; Moberly & Watkins, 2008), and items were pilot-tested for clarity and feasibility of completion prior to the study. Rumination: “At the time of the beep, I was dwelling on my feelings and problems.” Worry: “At the time of the beep, I was worried about things that could happen.”

In order to index the reliability of the rumination and worry items in the present study, the intraclass correlation (ICC) was computed for each item as the proportion of inter-subject variability to total variability using restricted maximum likelihood estimates. This statistic represents the average correlation between ratings on an item at two randomly selected time points for a given participant (Snijders & Bosker, 2011):

The significance of each ICC value was then evaluated using a Wald test, H0: ICC = 0 (Snijders & Bosker, 2011). ICC values were significantly greater than 0 for both rumination, ICC = 0.35, Z = 5.58, p < .001, and worry, ICC = 0.43, Z = 5.66, p < .001, indicating appropriate within-subject dependencies or nesting of observations within participants. Notably, Moberly and Watkins (2008) obtained an equivalent ICC value for ESM-assessed rumination (ICC = .34).

In order to index the convergent and discriminant validity of the rumination and worry items, participants’ mean ratings on these items were examined in relation to their scores on the canonical self-report questionnaires of rumination and worry (see Results section, below).

Theorized Features of Rumination and Worry

At each prompt, participants responded to nine items concerning the theorized features of rumination and worry. Item content was drawn from theory (reviewed in Borkovec et al., 2004, Ehring & Watkins, 2008, and Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008) and previous ESM and laboratory studies of rumination and worry (e.g., Borkovec & Inz, 1990; Lyubomirsky et al., 1999; McLaughlin et al., 2007; Moberly & Watkins, 2008), and items were pilot-tested for clarity and feasibility of completion prior to the study. Four items assessed the theorized shared features of rumination and worry. Unpleasantness: Participants rated their thoughts at the time of the beep using a five-point scale (1 = very unpleasant, 5 = very pleasant). We subsequently reverse-coded this item such that higher ratings index greater unpleasantness. Repetitiveness: Participants rated the degree to which their thoughts “felt repetitive or stuck” at the time of the beep using a 100-point visual analog scale (1 = not at all, 100 = very much so). Abstractness: Participants rated their thoughts at the time of the beep using a five-point scale (1 = very concrete/specific, 5 = very abstract/general). Uncontrollability: Participants rated the degree to which they were able to control their thoughts at the time of the beep using a 100-point visual analog scale (1 = not at all, 100 = very much so). We subsequently reverse-coded this item such that higher ratings index greater uncontrollability.

Five items assessed the theorized distinct features of rumination and worry. Temporal orientation: Participants reported whether their thoughts were mostly about the “past,” “present,” or “future” at the time of the beep by selecting one of these three forced-choice response options. Self focus: Participants reported whether their thoughts were mostly about “myself” or “not myself” at the time of the beep by selecting one of these two forced-choice response options. Verbal-linguistic focus: Participants reported whether their mind was mostly filled with “images” or “words” at the time of the beep by selecting one of these two forced-choice response options. Situational certainty/uncertainty: Participants rated the degree to which they “felt a sense of certainty about situations” at the time of the beep using a 100-point visual analog scale (1 = not at all, 100 = very much so). For the models predicting worry, we subsequently reverse-coded this item such that higher ratings index greater uncertainty. Situational control/lack of control: Finally, participants rated the degree to which they “felt a sense of control over situations” at the time of the beep using a 100-point visual analog scale (1 = not at all, 100 = very much so). For the models predicting rumination, we subsequently reverse-coded this item such that higher ratings index greater lack of control.

In order to index the reliability of the theorized features of rumination and worry, the ICC was computed for each ESM item and the significance of each ICC value was evaluated using a Wald test, H0: ICC = 0 (Snijders & Bosker, 2011). ICC values were significantly greater than 0 for all theorized features of rumination and worry: unpleasantness, ICC = 0.24, Z = 5.32, p < .001, repetitiveness, ICC = 0.39, Z = 5.63, p < .001, abstractness, ICC = 0.26, Z = 5.37, p < .001, uncontrollability, ICC = 0.42, Z = 5.63, p < .001, past orientation, ICC = 0.04, Z = 3.19, p = .001, future orientation, ICC = 0.13, Z = 4.88, p < .001, self focus, ICC = 0.18, Z = 5.02, p < .001, verbal-linguistic focus, ICC = 0.22, Z = 5.21, p < .001, situational certainty/uncertainty, ICC = 0.47, Z = 5.69, p < .001, and situational control/lack of control, ICC = 0.43, Z = 5.67, p < .001. These results indicate appropriate within-subject dependencies or nesting of observations within participants.

There are no questionnaires that assess the multiple specific features of rumination and worry (e.g., unpleasantness of thinking) independent of these broader constructs. Therefore, information is not currently available concerning the convergent and discriminant validity of these ESM-assessed thought features with questionnaire-based assessments.

Self-Report Questionnaires

Prior to the ESM protocol, participants completed several self-report questionnaires. To assess the severity of MDD and GAD symptoms, participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-IV (GAD-Q-IV; Newman et al., 2002), respectively, both of which have strong psychometric properties (e.g., Dozois, Dobson, & Ahnberg, 1998; Robinson, Klenck, & Norton, 2010). In the present sample, internal consistency was strong among the items of the BDI-II (α = .96) and among the dimensional items of the GAD-Q-IV (α = .81), with the dichotomous items summed to treat them as a continuous item as was done in a previous psychometric analysis (Rodebaugh, Holaway, & Heimberg, 2008). In order to examine the relations of our ESM measures to scores on the traditional self-report measures of rumination and worry, we used the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS; Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003) and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990), respectively. We specifically used the RRS Brooding Subscale as the canonical measure of maladaptive rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Treynor et al., 2003). Both the RRS Brooding Subscale and the PSWQ have excellent psychometric properties (e.g., Molina & Borkovec, 1994; Treynor et al., 2003). Internal consistency in our sample was high among the items of the RRS Brooding Subscale (α = .87) and of the PSWQ (α = .94).

Statistical Analyses

Based on the nested structure of the ESM data (prompts nested within persons), we tested our hypotheses using multilevel modeling. Multilevel modeling concurrently estimates within- and between-persons effects (Krull & Mackinnon, 2001) while allowing for variable time intervals between sampling occasions and missing data (Snijders & Bosker, 2011). We used the software HLM 6.08 (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2004); all models were random effects models in which the intercepts and slopes were allowed to vary, and we use robust standard errors when reporting all parameter estimates. In all equations below, i denotes prompts and j denotes participants. Whenever any participant group (e.g., CTL group) is included as a Level 2 (between-persons) variable, it is dummy-coded (0 = participant is not in that group; 1 = participant is in that group).

Finally, significance values for all effects are followed by the pseudo-R2 estimate of within- or between-subject variance explained within the model (Singer & Willett, 2003); however, these values should be interpreted with caution. As discussed in Snijders and Bosker (2011), multilevel modeling is not favorable to traditional computations of effect size or proportion of variance explained (e.g., R2). The statistic that is most often used, pseudo-R2, represents the difference in (within- or between-person) variance in the full model containing all predictors and (within- or between-person) variance in the comparison model in which only the predictor of interest is removed. Because removing one predictor of interest from the model changes the amount of variance explained by both the other Level-1 and Level-2 predictors, the pseudo-R2 value that is obtained is typically a lower-level estimate and is not directly interpretable. As a clear example of this issue, in many multilevel modeling contexts, the addition of a predictor variable serves to decrease rather than increase the proportion of variance explained by the model (e.g., adding a Level-2 predictor may reduce the between-group variance but increase the within-group variance), resulting in a negative pseudo-R2 value (Hox, 2002). For all of these reasons, we caution that the pseudo-R2 values should not be considered actual estimates of variance explained.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the MDD, GAD, MDD-GAD, and CTL groups are presented in Table 1. There were no group differences in age, F(3,66) = 0.94, p = .43, η2 = .04, proportion of college-educated participants, χ2(3, N = 70) = 0.08, p = .99, Cramer’s V = .03, distribution by race/ethnicity, χ2(15, N = 70) = 14.93, p = .46, Cramer’s V = .27, or percentage of prompts completed, F(3,66) = 0.64, p = .59, η2 = .03. Significant pairwise comparisons on the BDI-II, GAD-Q-IV, RRS Brooding Subscale, PSWQ, and DSM Global Axis of Functioning (GAF) are denoted in Table 1. Importantly, the MDD-GAD group did not differ from the MDD group in BDI-II score, p = .39, d = 0.25, and the MDD-GAD group did not differ from the GAD group in GAD-Q-IV sore, p = .55. d = 0.28.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the MDD, GAD, MDD-GAD, and CTL Groups

| Variable |

MDD |

GAD |

MDD-GAD |

CTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M (SD) or % |

M (SD) or % |

M (SD) or % |

M (SD) or % |

|

| Age | 31.56 (10.28) | 31.07 (6.97) | 35.50 (10.10) | 34.68 (9.88) |

| % college educated | 68.8% | 66.7% | 65.0% | 68.4% |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 50.0% | 66.7% | 60.0% | 66.7% |

| Hispanic | 0% | 13.3% | 10.0% | 0% |

| African-American | 6.3% | 0% | 5.0% | 11.1% |

| Asian-American | 18.8% | 20.0% | 15.0% | 5.6% |

| Mixed Race/Other | 25.0% | 0% | 10.0% | 16.7% |

| % prompt completion | 57.3% | 65.5% | 68.3% | 65.1% |

| BDI-II | 28.25 (8.56) c | 14.20 (9.56) b | 30.70 (10.63) c | 1.47 (2.63) a |

| GAD-Q-IV | 8.01 (4.03) b | 10.94 (1.13) c | 10.38 (2.62) c | 1.89 (2.23) a |

| RRS Brooding* | 13.44 (2.66) b | 11.93 (4.00) b | 15.50 (2.65) c | 6.44 (1.20) a |

| PSWQ | 55.19 (15.20) b | 68.07 (6.66) c | 61.00 (13.26) b,c | 40.79 (12.48) a |

| GAF | 55.94 (5.18) c | 64.13 (5.69) b | 54.45 (6.09) c | 89.37 (8.75) a |

Note. MDD = current major depressive disorder; GAD = current generalized anxiety disorder; MDD-GAD = current major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder; CTL = no past or current psychiatric disorder; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; GAD-Q-IV = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-IV; RRS Brooding = Ruminative Response Scale Brooding Subscale; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; GAF = Global Axis of Functioning.

For each variable, data were missing for one CTL participant.

Different superscripts within rows indicate significant pairwise comparisons, p < .05.

Relations Between ESM Measures and Self-Report Questionnaires

To index the convergent and discriminant validity of ESM-assessed rumination and worry, we used multilevel modeling to test the associations of mean ratings on the ESM rumination and worry items with participants’ scores on the RRS Brooding Subscale and PSWQ (entered as Level 2 predictors centered at the grand mean, covarying the effect of CTL group; accordingly, Level-2 pseudo-R2 values are reported).

Level 1 Models (prompt level; same equation used for rumination and worry):

Level 2 Models (participant level; same equation used for rumination and worry):

Mean level of rumination was uniquely associated with RRS Brooding Subscale score, p < .05, pseudo-R2 = .04, but not with PSWQ score, p = .26, pseudo-R2 = .01. Similarly, mean level of worry was uniquely associated with PSWQ score, p < .05, pseudo-R2 = .05, but not with RRS Brooding Subscale score, p = .58, pseudo-R2 = −.01. These results indicate appropriate convergent and discriminant validity of ESM-assessed rumination and worry.

Rumination and Worry as Transdiagnostic Constructs in Daily Life

In order to examine mean levels of ESM-assessed rumination and worry across groups, we conducted means-as-outcomes models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) separately for rumination and worry and centered for each participant.

Level 1 Models (prompt level; same equation used for rumination and worry):

Level 2 Models (participant level; same equation used for rumination and worry):

In the Level 1 model above, Ruminationij or Worryij denotes the level of rumination or worry, respectively, for participant j at prompt i. rij denotes the within-person random effect. In the Level 2 model above, γ00 denotes the mean level of rumination or worry for the CTL group; γ01, γ02, and γ03 denote the differences in mean level of rumination or worry between the CTL group and the MDD group, GAD group, and MDD-GAD group, respectively. u0j denotes the between-persons random effect. As this Level 2 model only tests comparisons between the CTL group and all other groups, we conducted two additional analogous Level 2 models in which the remaining group comparisons (e.g., MDD vs. GAD) were tested. Accordingly, Level-2 pseudo-R2 values are reported.

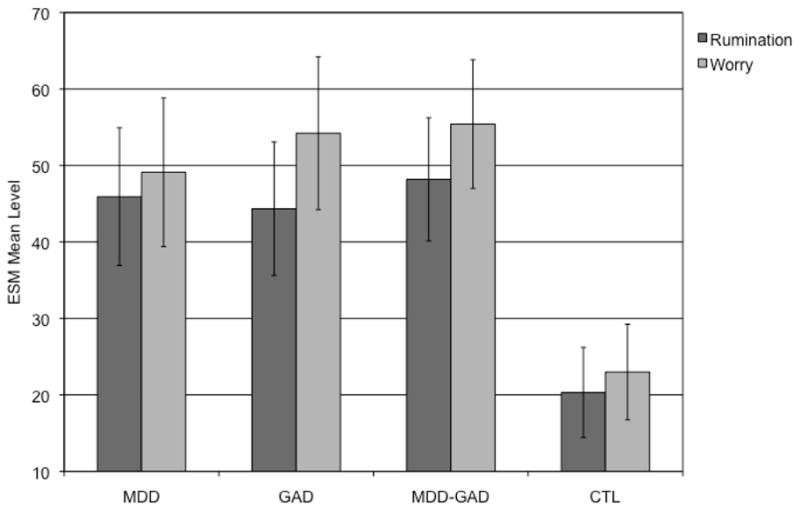

Mean levels of rumination and worry across the MDD, GAD, MDD-GAD, and CTL groups are presented in Figure 1. Results of the means-as-outcomes models for rumination demonstrated that mean levels of rumination in the MDD group (M = 45.92, SE = 4.59), GAD group (M = 44.35, SE = 4.45), and MDD-GAD group (M = 48.20, SE = 4.11) all were significantly higher than was mean level of rumination in the CTL group (M = 20.33, SE = 3.01), all ps < .001, all pseudo-R2s > .30. Mean levels of rumination across the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups did not differ significantly from one another, all ps > .38, all pseudo-R2s < .00. Similarly, results of the means-as-outcomes models for worry demonstrated that mean levels of worry in the MDD group (M = 49.13, SE = 4.96), GAD group (M = 54.23, SE = 5.10), and MDD-GAD group (M = 55.42, SE = 4.29) all were significantly higher than was mean level of worry in the CTL group (M = 23.00, SE = 3.19), all ps < .001, all pseudo-R2s > .30. Again, mean levels of worry across the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups did not differ significantly from one another, all ps > .19, all pseudo-R2s < .01.

Figure 1.

Mean levels of ESM-assessed rumination and worry in the MDD, GAD, MDD-GAD, and CTL groups. MDD = current major depressive disorder; GAD = current generalized anxiety disorder; MDD-GAD = current major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder; CTL = no past or current psychiatric disorder. Error bars denote 95% confidence interval. The MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups all report significantly higher levels of both rumination and worry than does the CTL group, all ps < .001. The MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups do not significantly differ from one another in levels of rumination, all ps > .38, or worry, all ps > .19.

Naturalistic Construct Validity of Rumination and Worry

In order to examine the naturalistic validity of these constructs, we conducted two multilevel analyses predicting levels of rumination and worry, respectively, at a given prompt as a function of their theorized features within the same prompt. That is, we tested the unique contribution of each theorized feature to each overall construct at that same point in time. Accordingly, Level-1 pseudo-R2 values are reported.

Rumination

For the model predicting rumination at a given prompt, the Level 1 predictors were thought unpleasantness, repetitiveness, abstractness, uncontrollability, past orientation (dummy coded: 0 = not past-oriented; 1 = past-oriented), self focus (dummy-coded: 0 = not self-focused; 1 = self-focused), situational certainty, and situational lack of control, at that same prompt. All continuous predictors were person-centered. Given that across all participants levels of rumination and worry were associated within prompts, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .09, we covaried level of worry at that same prompt in order to examine the specific relations of these features to rumination.

Level 1 Model (prompt level):

With respect to new denotations, β1j denotes the association between level of unpleasantness of thoughts and level of rumination for participant j; this same denotation holds for β2j to β8j as the other theorized features of rumination.

At Level 2, we tested the construct validity of rumination in MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD; because the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups did not differ in their mean levels of these constructs and in order to maximize statistical power, we initially conducted the Level 2 models using clinical group (i.e., the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups combined) as the reference group. Accordingly, the CTL group was entered as the contrast group at Level 2 (i.e., clinical group = 0; CTL group = 1).

Level 2 Models (participant level):

With respect to new denotations, γ00 denotes the mean level of rumination in the clinical group, and γ01 denotes the difference in mean level of rumination between the clinical group and the CTL group. γ10 denotes the association between level of unpleasantness of thoughts and level of rumination in the clinical group, and γ11 denotes the difference in this association between the clinical group and the CTL group. This same denotation holds for γ20 to γ91.

Full results for the model predicting rumination are presented in Table 2. As hypothesized, in the clinical group level of rumination was significantly and uniquely associated with level of unpleasantness, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .06, repetitiveness, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .09, and uncontrollability, p = .01, pseudo-R2 = .02, of thoughts. Level of rumination was also significantly and uniquely associated with past orientation, p = .01, pseudo-R2 = .01, and self focus, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .01, of thoughts, and with a sense of lack of control over situations, p < .01, pseudo-R2 = .01. Contrary to expectations, however, level of rumination was not associated with level of abstractness of thoughts, p = .44, pseudo-R2 = .01, or with a sense of certainty about situations, p = .31, pseudo-R2 = .01. Collectively, the Level 1 predictors explained 56.24% of the within-subjects variance in level of rumination. Although not the focus of our investigation, contrasts between the clinical and CTL groups are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multilevel Model Predicting Level of Rumination as a Function of Theorized Features within Prompts

| Predictor | Unstd. Coeff. | SE | t(68) | Group Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unpleasantness (β1j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ10) | 5.89 | 0.71 | 8.33*** | MDD > MDD-GAD* |

| CTL group contrast (γ11) | −3.65 | 1.18 | −3.09** | Clinical > CTL** |

| Repetitiveness (β2j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ20) | 0.27 | 0.03 | 7.85*** | |

| CTL group contrast (γ21) | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.15 | |

| Abstractness (β3j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ30) | −0.32 | 0.42 | −0.77 | |

| CTL group contrast (γ31) | 1.25 | 0.59 | 2.12* | CTL: sig.* |

| Uncontrollability (β4j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ40) | 0.08 | 0.03 | 2.94** | |

| CTL group contrast (γ41) | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.40 | |

| Past orientation (β5j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ50) | 4.35 | 1.66 | 2.62* | |

| CTL group contrast (γ51) | 2.51 | 3.75 | 0.67 | |

| Self focus (β6j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ60) | 2.15 | 1.05 | 2.05* | |

| CTL group contrast (γ61) | −1.29 | 1.22 | −1.05 | |

| Situational certainty (β7j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ70) | −0.03 | 0.03 | −1.02 | GAD: sig. in opposite direction** |

| CTL group contrast (γ81) | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.03 | |

| Situational lack of control (β9j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ90) | 0.10 | 0.03 | 3.00** | |

| CTL group contrast (γ91) | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.11 | |

Note. MDD = current major depressive disorder; GAD = current generalized anxiety disorder; MDD-GAD = current major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder; CTL = no past or current psychiatric disorder. Clinical group represents the estimate in the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups combined. CTL group contrast represents the difference between the estimates in the clinical group and the CTL group. Group differences are denoted only when they are statistically significant.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

Significantly stronger effect.

Finally, in order to test the possibility of any differences among the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups in the relations of these theorized features to rumination, we conducted a follow-up set of Level 2 models, with each model using the MDD, GAD, or MDD-GAD group, respectively, as the reference group.

Level 2 Models (participant level; example using MDD group as reference group):

As shown in Table 2, there were only two significant differences among the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups in the relations of these features to rumination. First, the association between level of unpleasantness of thoughts and level of rumination was slightly stronger in the MDD group than in the MDD-GAD group, p = .04, pseudo-R2 = .00. Second, in the GAD group, a sense of uncertainty about situations was significantly associated with level of rumination, p = .01, pseudo-R2 = .00; this was not the case in the MDD and MDD-GAD groups.

Worry

For the model predicting worry at a given prompt, the Level 1 predictors were thought unpleasantness, repetitiveness, abstractness, uncontrollability, future orientation (dummy coded: 0 = not future-oriented; 1 = future-oriented), verbal-linguistic focus (dummy-coded: 0 = not verbal-linguistic; 1 = verbal-linguistic), situational uncertainty, and situational control, at that same prompt. All continuous predictors were person-centered. Given that across all participants levels of rumination and worry were associated within prompts, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .09, we covaried level of rumination at that same prompt in order to examine the specific relations of these features to worry.

Level 1 model (prompt level):

The same denotations for the Level 1 and Level 2 models predicting Ruminationij, above, hold for the models predicting Worryij. Also consistent with the analyses for rumination, we initially conducted the Level 2 models for worry using clinical group (i.e., the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups combined) as the reference group and the CTL group as the contrast group.

Full results for the model predicting worry are presented in Table 3. As hypothesized, in the clinical group level of worry was significantly and uniquely associated with level of unpleasantness, p < .01, pseudo-R2 = .02, and repetitiveness, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .01, of thoughts. Level of worry was also significantly and uniquely associated with future orientation, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .03, and verbal-linguistic focus, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .01, of thoughts, and with a sense of uncertainty about situations, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .05. Contrary to expectations, however, level of worry was not associated with level of uncontrollability of thoughts, p = .38, pseudo-R2 = .01. In addition, worry was associated with greater concreteness rather than abstractness of thoughts, p < .01, pseudo-R2 = .01, and with a sense of lack of control rather than control over situations, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = .05. Collectively, the Level 1 predictors explained 49.82% of the within-subjects variance in level of worry. Although not the focus of our investigation, contrasts between the clinical and CTL groups are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multilevel Model Predicting Level of Worry as a Function of Theorized Features within Prompts

| Predictor | Unstd. Coeff. | SE | t(68) | Group Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unpleasantness (β1j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ10) | 2.27 | 0.70 | 3.23** | |

| CTL group contrast (γ11) | 0.54 | 0.94 | 0.58 | |

| Repetitiveness (β2j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ20) | 0.10 | 0.02 | 4.24*** | |

| CTL group contrast (γ21) | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.76 | |

| Abstractness (β3j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ30) | −1.37 | 0.42 | −3.27** | |

| CTL group contrast (γ31) | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.86 | |

| Uncontrollability (β4j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ40) | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.89 | MDD-GAD: sig. in opposite direction* |

| CTL group contrast (γ41) | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.31 | |

| Future orientation (β5j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ50) | 6.90 | 0.96 | 7.16*** | |

| CTL group contrast (γ51) | −3.20 | 1.52 | −2.11* | Clinical > CTL* |

| Verbal-linguistic focus (β6j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ60) | 3.40 | 0.89 | 3.84*** | |

| CTL group contrast (γ61) | −1.58 | 1.58 | −1.00 | |

| Situational uncertainty (β7j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ70) | 0.21 | 0.04 | 5.11*** | MDD-GAD > GAD* |

| CTL group contrast (γ81) | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.56 | |

| Situational control (β9j) | ||||

| Clinical group (γ90) | −0.17 | 0.04 | −3.88*** | |

| CTL group contrast (γ91) | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.18 | |

Note. MDD = current major depressive disorder; GAD = current generalized anxiety disorder; MDD-GAD = current major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder; CTL = no past or current psychiatric disorder. Clinical group represents the estimate in the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups combined. CTL group contrast represents the difference between the estimates in the clinical group and the CTL group. Group differences are denoted only when they are statistically significant.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

Significantly stronger effect.

In order to test the possibility of any differences among the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups in the relations of these theorized features to worry, we conducted a follow-up set of Level 2 models, with each model using the MDD, GAD, or MDD-GAD group, respectively, as the reference group. The same denotations for the Level 1 and Level 2 models predicting Ruminationij, above, hold for the models predicting Worryij. As shown in Table 3, there were only two significant differences among the MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD groups in the relations of the theorized features to worry. First, the association between a sense of uncertainty about situations and level of worry was slightly stronger in the MDD-GAD group than in the GAD group, p = .01, pseudo-R2 = .00. Second, in the MDD-GAD group, level of controllability of thoughts was significantly associated with level of worry, p = .01, pseudo-R2 = .00; this was not the case in the MDD and GAD groups.

Discussion

In the present study, participants diagnosed with MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD all were found to be characterized by high and equivalent levels of rumination and worry in daily life. In addition, participants’ momentary reports of their thoughts provided strong support for multiple theorized components of these thought processes, while also suggesting that some features are not as integral to conceptualizations of rumination and worry as traditionally has been thought. Most notably, rumination and worry shared core features of unpleasantness, repetitiveness, and a sense of situational lack of control, but were distinguished by temporal orientation, core content, and a sense of situational uncertainty. Moreover, persons with MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD reported similar relations of rumination and worry to each of their theorized features, supporting conceptualizations of rumination and worry as core processes that transect specific clinical syndromes. Finally, providing a strong foundation for all of these conclusions, the ESM items assessing rumination and worry showed appropriate convergent and discriminant validity with scores on the traditional self-report questionnaires assessing these constructs. Below, we discuss implications of these findings for clinical theory and assessment along with limitations of this study and directions for future research.

Results of the models predicting rumination supported the majority of theoretical postulates (reviewed in Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Rumination was experienced as highly unpleasant, repetitive, and uncontrollable, and thought content was past-oriented and self-focused. Participants also associated this process strongly with a sense of lack of control over situations. Importantly, each of these theorized features contributed uniquely to the overall construct of rumination. In contrast to predictions, however, ruminative thought was not rated as abstract or over-general and was not associated with a sense of certainty about situations. With respect to abstractness, some theorists have posited that there are two types of rumination: concrete and abstract (Watkins & Moulds, 2005); it is possible that the clinical participants in this study were engaging in both forms of rumination, which may have led us to obtain a nonsignificant effect. It is also possible that under natural conditions people experience their thoughts as more specific or more strongly tied to external events than they do in the laboratory; in future research, therefore, it will be important to assess more explicitly the frequency of and conditions surrounding abstract thinking in daily life. Finally, whereas rumination was not associated with a sense of certainty or uncertainty about situations across the full clinical sample, participants with GAD uniquely reported a strong link between rumination and a sense of uncertainty. This finding is intriguing in light of previous work on worry and uncertainty in GAD (e.g., Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas, & Ladouceur, 1994), and suggests that for persons with GAD a sense of uncertainty is more broadly associated with perseverative thinking rather than specifically related to worry.

Findings for the models predicting worry were similarly supportive of multiple theoretical formulations (reviewed in Borkovec et al., 2004). Worry was experienced as highly unpleasant and repetitive, and was characterized by future-oriented and verbal-linguistic modes of thinking. This latter finding was particularly striking given the coarse nature of our verbal-linguistic ESM item. In addition, worry was strongly associated with a sense of uncertainty about situations. Again, each of these features contributed independently to the overall construct of worry. Unexpectedly, however, worry was not reported as uncontrollable across the full clinical sample, and participants with co-occurring MDD-GAD reported an association between controllability of thinking and level of worry. Importantly, participants with MDD-GAD also reported a stronger sense of uncertainty in worry than did participants with GAD alone; thus, worry may be a particularly pernicious process in MDD-GAD (see also Dupuy & Ladouceur, 2008). Future research should attempt to replicate this comorbidity-specific effect and investigate the potential for unique correlates and consequences of worry in co-occurring MDD-GAD. Also contrary to expectations, worry was associated with reports of concrete rather than abstract thinking and, like rumination, was identified with a sense of lack of control over situations. It is possible that individuals experience worry in daily life as tied (at least initially) to particular upcoming events or threats, and that in its persistence worry becomes increasingly abstract, verbal, and unproductive (Stöber, 1998). Follow-up ESM analyses may assess patterns of worry over time (e.g., in relation to daily events) and whether the persistence of worry is associated with increases or decreases in abstractness and sense of control over situations.

Taken together, evidence for both worry and rumination in daily life provides strong support for perseverative thought as an overarching process across MDD, GAD, and MDD-GAD (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Harvey et al., 2004). Specifically, rumination and worry shared several core features of unpleasantness, repetitiveness, and a sense of situational lack of control. Rumination and worry also co-occurred at high levels in all clinical participants. Evidence for distinct features including temporal orientation, core content, and sense of situational certainty demonstrate that while rumination and worry are highly related, they are also distinguishable. Indeed, results concerning distinct features indicate that individuals are able to discriminate between these two processes in their daily lives. ESM enables the rare opportunity to examine individuals’ thought processes in dynamic relation to other aspects of their daily lives, providing insights that cannot be achieved solely through the use of static or laboratory measures. It will be important in future ESM investigations to extend the present findings by examining the common and distinct relations of rumination and worry to other key variables (e.g., daily stressors).

Four limitations of the present study warrant discussion. First, with respect to the available psychometric data for our ESM items, there are no questionnaires that assess the specific features of rumination and worry (e.g., unpleasantness of thinking) independently of these broader constructs; moreover, we did not use any laboratory procedures to assess these thought features. Therefore, we were not able to compute the associations of our thought feature items with other measures. In future, the development and standardization of alternative methods to assess these thought features will facilitate the evaluation of convergent and discriminant validity. Second, our sample size was slightly smaller than those in previous laboratory studies of MDD and of GAD. This was due, in part, to our deliberate separation of participants with MDD alone, GAD alone, and co-occurring MDD-GAD, and challenges in recruiting participants who met current diagnostic criteria for MDD or GAD without having experienced the other disorder within the past two years. Indeed, MDD and GAD have very high rates of lifetime comorbidity (e.g., Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001; Judd et al., 1998). Thus, this smaller sample size may be offset by our ability to detect group differences using this recruitment strategy. ESM is also advantageous in this context in providing a large number of data points for each participant. Third, we restricted our sample to women in order to strengthen statistical power, particularly given that women have been found to engage in perseverative thought more frequently than do men (reviewed in Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Future research should include samples of both men and women who are diagnosed with various forms of psychopathology in order to examine the generalizability of these constructs. Similarly, future ESM studies should also explore rumination, worry, and other thought processes across diverse forms of psychopathology in order to replicate these findings. Fourth, while prompt response rates did not differ significantly among the groups, the overall response rate was slightly lower than that in a previous ESM study in our laboratory (see Thompson et al., 2012). However, other ESM-based investigators have obtained lower response rates than that reported in this study (e.g., Hartley et al., 2014). Participants in the present study received a pre-set compensation and bonus incentive for their completion of ESM; it is possible that a titrated compensation schedule would be more effective in increasing response rates.

In sum, we used a theory-driven ESM approach to shed fresh light on rumination and worry and to stimulate further empirical and clinical applications. In considering future research on these constructs, one of the most pressing questions will be how to utilize data to develop more personalized understanding of and interventions for rumination and worry (consistent with National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH] Strategic Objective 3.2; Insel, 2009). ESM enables unique insight into the naturalistic within-person dynamics of rumination and worry and, in so doing, can provide individualized information concerning the precipitants, correlates, and consequences of these forms of perseverative thinking. The current results indicate that assessing thought unpleasantness, repetitiveness, uncontrollability, and situational lack of control is particularly important in an integrative experience sampling examination of rumination and worry. In the context of cogent arguments presented in Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (2008), future ESM investigations should pay particular attention to the functions served by different forms of perseverative thought for individuals in daily life; these include non-conscious functions that participants may not report directly, but that can be revealed through ESM-assessed dynamics of these thought processes in relation to other key factors (e.g., daily events, affective experiences). The results obtained from personalized assessment can then be used to develop person-centered interventions that target the particular precipitants or functions served by rumination and worry for each individual, which may be more effective than traditional interventions that focus on treating the typical or average individual (Fisher, under review). Such applications would also help to bridge the gap between assessments conducted in the laboratory and individuals’ daily functioning. Sophisticated methodological and analytic approaches to naturalistic data increase our ability to test clinical theories, develop personalized interventions, and encourage new research questions that could not before be asked.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Lemus and Cat Camacho for their help in data collection.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH096385 to Katharina Kircanski, MH091831 to Renee J. Thompson, and MH059259 to Ian H. Gotlib), and the National Science Foundation (Graduate Research Fellowship to Lindsey Sherdell). All authors report no competing or financial interests.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

K.K. developed the study concept. K.K., R.J.T., J.E.S., L.S., and I.H.G. contributed to the design of the experience sampling protocol. K.K. performed the data analysis and interpretation under the supervision of R.J.T. and I.H.G. K.K. drafted the paper. R.J.T., J.E.S., L.S., and I.H.G. provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

References

- Alloy L, Kelly K, Mineka S, Clements C. Comorbidity in anxiety and depressive disorders: A helplessness/hopelessness perspective. In: Maser JD, Cloninger CR, editors. Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1990. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Hobbs MJ, Borkovec TD, Beesdo K, Craske MG, Heimberg RG, Stanley WMA. Generalized worry disorder: A review of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder and options for DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(2):134–147. doi: 10.1002/da.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35(2):205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett DJ, Feldman-Barrett L. The experience sampling program (ESP) 2000 Available at http://www.experience-sampling.org/

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Alcaine OM, Behar E. Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In: Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Mennin DS, editors. Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice. NY: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Inz J. The nature of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: A predominance of thought activity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28(2):153–158. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90027-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Robinson E, Pruzinsky T, DePree JA. Preliminary exploration of worry: Some characteristics and processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1983;21(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(4):585–599. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma LM, Taylor-Clift A, Rottenberg J. Emotional reactivity to daily events in major and minor depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(1):155–167. doi: 10.1037/a0021662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney RE, Joormann J, Eugène F, Dennis EL, Gotlib IH. Neural correlates of rumination in depression. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;10(4):470–478. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10(2):83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy JB, Ladouceur R. Cognitive processes of generalized anxiety disorder in comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(3):505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Watkins ER. Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2008;1(3):192–205. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Clinician Version (SCID-CV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AJ. Toward a dynamic model of psychological assessment: Implications for personalized care. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000026. under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeston MH, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R. Why do people worry? Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;17(6):791–802. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley S, Haddock G, Vasconcelos ESaD, Emsley R, Barrowclough C. An experience sampling study of worry and rumination in psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44(8):1605–1614. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Watkins E, Mansell W, Shafran R. Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: A strategic plan for research on mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:128–133. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Kessler RC, Paulus MP, Zeller PV, Wittchen HU, Kunovac JL. Comorbidity as a fundamental feature of generalized anxiety disorders: Results from the National Comorbidity Study (NCS) Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum. 1998;393:6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb05960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Gatz M, Pedersen NL. The sources of comorbidity between major depression and generalized anxiety disorder in a Swedish national twin sample. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37(03):453–462. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, DuPont RL, Berglund P, Wittchen HU. Impairment in pure and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depression at 12 months in two national surveys. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(12):1915–1923. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircanski K, Joormann J, Gotlib IH. Cognitive aspects of depression. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2012;3(3):301–313. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, Mackinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36(2):249–77. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AE, Liverant GI, Rosellini AJ, Brown TA. Generalized anxiety disorder within the course of major depressive disorder: Examining the utility of the DSM-IV hierarchy rule. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26(10):909–916. doi: 10.1002/da.20607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Tucker KL, Caldwell ND, Berg K. Why ruminators are poor problem solvers: Clues from the phenomenology of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(5):1041–1060. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A, MacLeod C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:167–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Borkovec TD, Sibrava NJ. The effects of worry and rumination on affect states and cognitive activity. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38(1):23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28(6):487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberly NJ, Watkins ER. Ruminative self-focus and negative affect: An experience sampling study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):314–323. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberly NJ, Watkins ER. Negative affect and ruminative self-focus during everyday goal pursuit. Cognition & Emotion. 2010;24(4):729–739. doi: 10.1080/02699930802696849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina S, Borkovec TD. The Penn State Worry Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and associated characteristics. In: Davey GCL, Tallis F, editors. Worrying: Perspectives on theory, assessment, and treatment. New York: Wiley; 1994. pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Oorschot M, Collip D, Lataster J, Delespaul P, van Os J. Experience sampling research in psychopathology: Opening the black box of daily life. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39(09):1533–1547. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby JM, Williams AD, Andrews G. Reductions in negative repetitive thinking and metacognitive beliefs during transdiagnostic internet cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for mixed anxiety and depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;59:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Zuellig AR, Kachin KE, Constantino MJ, Przeworski A, Erickson T, Cashman-McGrath L. Preliminary reliability and validity of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-IV: A revised self-report diagnostic measure of generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33(2):215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. Effects of rumination and distraction on naturally occurring depressed mood. Cognition & Emotion. 1993;7(6):561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(5):400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou C. Worry and rumination: Styles of persistent negative thinking in anxiety and depression. In: Davey GCL, Wells A, editors. Worry and its psychological disorders: Theory, assessment, and treatment. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing; 2006. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. Process and meta-cognitive dimensions of depressive and anxious thoughts and relationships with emotional intensity. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 1999;6(2):156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Pasyugina I, Koval P, De Leersnyder J, Mesquita B, Kuppens P. Distinguishing between level and impact of rumination as predictors of depressive symptoms: An experience sampling study. Cognition & Emotion. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.932755. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulesu E, Sambugaro E, Torti T, Danelli L, Ferri F, Scialfa G, Sassaroli WS. Neural correlates of worry in generalized anxiety disorder and in normal controls: A functional MRI study. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(1):117–124. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai V, Steenburg LA, Ciesla JA, Roth T, Drake CL. A seven day actigraphy-based study of rumination and sleep disturbance among young adults with depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2014;77(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon R. HLM (Version 6) [Computer software] 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CM, Klenck SC, Norton PJ. Psychometric properties of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionniare for DSM-IV among four racial groups. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2010;39(4):251–261. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2010.486841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Holaway RM, Heimberg RG. The factor structure and dimensional scoring of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire for DSM-IV. Assessment. 2008;15(3):343–350. doi: 10.1177/1073191107312547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Seitchik AE, Gentes EL, Jones JD, Hallion LS. Perseverative thought: A robust predictor of response to emotional challenge in generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49(12):867–874. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Tsao JCI, Alden LE, Craske MG. Worry and rumination: Repetitive thought as a concomitant and predictor of negative mood. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24(6):671–688. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker R. Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. 2. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stöber J. Worry, problem elaboration and suppression of imagery: The role of concreteness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36(7–8):751–756. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RJ, Mata J, Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Jonides J, Gotlib IH. The everyday emotional experience of adults with major depressive disorder: Examining emotional instability, inertia, and reactivity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(4):819–829. doi: 10.1037/a0027978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen DK. The association between rumination and negative affect: A review. Cognition & Emotion. 2006;20(8):1216–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination Reconsidered: A Psychometric Analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27(3):247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins E, Moulds M. Distinct modes of ruminative self-focus: Impact of abstract versus concrete rumination on problem solving in depression. Emotion. 2005;5(3):319–328. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins E, Moulds M, Mackintosh B. Comparisons between rumination and worry in a non-clinical population. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43(12):1577–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yook K, Kim KH, Suh SY, Lee KS. Intolerance of uncertainty, worry, and rumination in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(6):623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]