Abstract

Objective:

The literature on whether readiness to change (RTC) alcohol use translates into actual change among college students is both limited and mixed, despite the importance of understanding naturalistic change processes. Few studies have used fine-grained, prospective data to examine the link between RTC and subsequent drinking behavior, and alcohol consequences in particular. The present study involves tests of whether (a) intraindividual changes in RTC are negatively associated with alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences from week to week, (b) the effect of RTC on use and consequences is direct versus mediated by change in alcohol use, and (c) the association between RTC and drinking behavior is moderated by gender.

Method:

Participants were 96 college student drinkers who completed a baselinesurvey and 10 weekly web-based assessments of RTC, alcohol use, and consequences.

Results:

Hierarchical linear models indicated that, as hypothesized, reporting greater RTC on a given week (relative to one’s average level of RTC) was negatively associated with alcohol use (measured by either drinks per week or frequency of heavy episodic drinking) and alcohol consequences the following week. Changes in use fully mediated the relationship between RTC and consequences. The prospective association between RTC and both alcohol use and consequences did not differ by gender.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that higher RTC translates into short-term reductions in alcohol use and in turn alcohol consequences, and highlight important avenues for future research.

Alcohol use among college students is widespread and is associated with a variety of negative consequences (Hingson et al., 2005; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). As a result, much effort has been focused on developing prevention and treatment methods that address hazardous alcohol use in this population. Readiness to change (RTC) is a construct that has been studied extensively in college students. RTC is central to the Transtheoretical Model of change (Prochaska et al., 1992), which assumes that individuals must possess an appropriate level or stage of RTC to best incorporate suggestions related to behavior change. RTC is theoretically dynamic (Prochaska et al., 1992), and treatments that target RTC attempt to shift the patient toward increased levels of motivation to reduce drinking (Harris et al., 2008; Rollnick, 1998). An understanding of RTC also has value in delineating drinking changes in a naturalistic context, such as the college drinking environment. Indeed, the majority of hazardous drinkers in college environments will not present for treatment (Caldeira et al., 2009), although many students do modify their drinking on their own.

As such, an understanding of naturalistic change processes is crucial for identifying which of these students will “mature out” of heavy drinking patterns associated with the college environment and which students may develop more chronic alcohol problems (Dawson et al., 2006; Jackson et al., 2001). RTC is a construct that may be an important predictor of such naturalistic change.

Thus, it is essential to establish whether readiness to change translates into actual change. There is equivocal evidence about the predictive validity of RTC. For example, both positive (Harris et al., 2008; Palfai et al., 2002; Shealy et al., 2007) and negative (Bertholet et al., 2012; Carey et al., 2007) associations between RTC and alcohol use have been observed. Still other studies have found no association between self-reported RTC and subsequent drinking (Borsari et al., 2009). As noted by Kaysen et al. (2009), this inconsistency in results across studies likely reflects differences in the assessment of drinking outcomes (e.g., alcohol use quantity vs. frequency vs. consequences) or RTC (e.g., treating RTC as a static construct in cross-sectional studies vs. a dynamic construct in longitudinal studies), populations assessed (e.g., college students vs. treatment-seeking individuals), and/or differences regarding whether other relevant variables were incorporated into analyses (e.g., moderators of RTC–drinking behavior associations). Much of the work to date on this topic leaves unanswered a number of questions that are important to address to help advance research on the associations between RTC and drinking behavior.

To elucidate the nature of the association between RTC and drinking behavior, it is important to use longitudinal designs to establish temporality among the variables. Because one’s stage or level of readiness is theoretically dynamic (Prochaska et al., 1992), and because drinking patterns themselves among students also tend to fluctuate a great deal day to day and week to week (Del Boca et al., 2004; Maggs et al., 2011), longitudinal studies should be designed in such a way as to capture proximal associations among RTC and drinking behavior over time. To date, there has been a relative lack of this type of fine-grained research. In one important exception, Kaysen et al. (2009) examined whether RTC predicted subsequent drinking behavior week to week over the course of 11 weeks in a sample of female college students. They found that on weeks when students reported more RTC relative to their average readiness levels, they also reported both intentions to drink less in the future and actual reductions in drinks per week the following week. In contrast to some other work calling into question the link between RTC and actual change, when looking at these variables at an intraindividual level, this study provided important information about the short-term predictive validity of RTC. Studies such as this one using multilevel modeling can allow us to tease apart prediction of behavior change within an individual, unlike other analytic approaches that only have capability to test predictors of behavior between individuals.

Despite the strengths of the Kaysen et al. (2009) study, important questions are left unanswered. First, in this work, only the association between RTC and a single indicator of alcohol use (drinks per week) was examined; unclear is whether RTC is associated with subsequent declines in indicators of alcohol use that might reflect greater risk (i.e., heavy episodic drinking [HED] frequency). Also unanswered is whether RTC is related to subsequent changes in alcohol-related consequences and whether such change is mediated by changes in alcohol use. Indeed, alcohol use explains only a portion of the variance in consequences (Read et al., 2007). Students who experience negative alcohol consequences may be motivated to change by attempting to drink in a way that would result in fewer consequences, even if they are not drinking less alcohol overall. For example, a student who is considering change may not drink less but may use protective behavioral strategies (Pearson, 2013), such as relying on a designated driver to avoid legal consequences or establishing a buddy system to avoid social consequences (e.g., sexual or physical assault). From a harm-reduction perspective, negative consequences are a target of intervention equally relevant as absolute level of alcohol use, making it important to establish whether changes in alcohol use as a function of RTC actually translate into changes in alcohol consequences. Although a few studies have examined both changes in alcohol use and consequences as a function of RTC (e.g., Collins et al., 2010), alcohol use and consequences have tended to be analyzed as separate outcomes in these studies, and the mediational role of changes in alcohol use in the link between RTC and subsequent changes in alcohol consequences remains unclear.

Second, the sample in the Kaysen et al. (2009) study comprised only female students, leaving unknown whether the within-person effects of RTC on changes in drinking behavior generalize to male students or differ between genders. This is important given that men and women drink at different levels and may also experience consequences differently (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004; Park and Grant, 2005). In addition, prior research demonstrates that women may be more likely to consider changing their drinking behavior (Barnett et al., 2006), and cross-sectional studies have found that gender moderates concurrent associations between RTC and drinking behavior (Foster, 2013). By extension, it is possible that associations between RTC and subsequent alcohol use and consequences may differ for men and women. However, to our knowledge, the moderating role of gender has not been examined with respect to weekly level associations between RTC and alcohol.

The present study sought to address these gaps by testing associations between RTC and both alcohol use and consequences from week to week in a sample of male and female college students. We had three aims. First, we replicated and extended the analyses by Kaysen et al. (2009) in a mixed-gender sample, hypothesizing that intraindividual changes in RTC would be negatively associated with alcohol use from week to week indexed by the weekly number of drinks (i.e., higher RTC one week would be associated with downward changes in alcohol use the next week; lower RTC would be associated with upward changes in alcohol use). We also extended past research by examining RTC’s association with a particular pattern of drinking that has been specifically linked to harmful outcomes, HED (Del Boca et al., 2004; Hingson et al., 2009; Masten et al., 2009). Second, we advanced the literature by testing whether RTC translates into an impact on alcohol-related consequences, hypothesizing that any effect of change in RTC on change in consequences would be mediated by changes in alcohol use. Finally, as an exploratory aim, we examined whether the association between RTC and actual change in either alcohol use or consequences was moderated by gender.

Method

Participants and recruitment procedures

All procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board. Participants were 96 college students, sampled from an ongoing longitudinal study examining traumatic stress and substance use among college students (Read et al., 2012). For this larger study, incoming students were recruited the summer before matriculation in three cohorts. The total sample for the larger study was 997 (Read et al., 2012); however, in the present study, we recruited from only the two consecutive cohorts at the primary study site (N = 773), which was a large, 4-year public university in the northeastern United States. At the time of data collection for the present study, all participants were in their junior or senior year of college. More than half (52.1%; n = 50) were female, and the average age was 20.92 years (SD = 0.52). For race, 82.3% (n = 79) self-identified as White, 7.3% (n = 7) as Asian, 5.2% (n = 5) as Hispanic/Latino, 2.1% (n = 2) as Black, and 3.1% (n = 3) as multiracial. Regarding residence, 62.5% (n = 60) lived off campus (not with family), 22% (n = 21) lived on campus, 13.5% (n = 13) lived at home with family, and 2% (n = 2) lived in fraternity/sorority housing.

Of the 773 participants in the larger study at the northeastern sites, we chose to sample from only the regular drinkers (at least once/week) who had also experienced at least one negative alcohol consequence over the past month (assessed by using the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire [B-YAACQ]; Kahler et al., 2005), because it is these drinkers, rather than the lighter drinkers or those without consequences, who would be most likely to consider changing their drinking. One hundred sixty-nine participants met these criteria, and personalized e-mails describing the study and inviting participation were sent in waves until we achieved our target N of 100. A total of 150 emails were sent to achieve this target; 100 participants provided informed consent for the present study (75% of those targeted for recruitment were enrolled). However, four participants did not provide enough data (i.e., at least 2 of 10 weekly assessments) to be included in the analytic models. Thus, the final sample size was 96. A power analysis based on an intraclass correlation (ICC) of .40, 10 weekly assessments, and a desired power of .80 to detect moderate effect sizes (δ = .50) indicated the need for 60 participants (Raudenbush & Xiao-Feng, 2001). As such, our analytic sample size of 96 was adequately powered to detect hypothesized effects using multilevel analysis.

Web-based assessment

Procedures are described in more detail elsewhere (Merrill et al., 2013). Briefly, using commercially available web-based assessment software, data were collected once per week (between Sunday and Monday) for 10 consecutive weeks in the spring semester. For each weekly survey (10-15 minutes), participants earned $2.50 (i.e., $25 over 10 weeks) in gift cards and a bonus of up to $40, depending on the number completed.

Measures

Demographics.

At baseline, participants reported gender, age, ethnicity, and educational status.

Alcohol use.

At each weekly assessment, participants reported the number of standard drinks consumed on each day in the past week, using a grid format modeled after the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985). The web survey page included a standard drink conversion chart indicating what constitutes a standard alcoholic drink. This measure allowed us to calculate two indicators of alcohol use: (a) weekly quantity (drinks per week), consistent with Kaysen et al. (2009), and (b) HED frequency (number of days per week on which the participant consumed 4+ [female] or 5+ [male] drinks).

Alcohol consequences.

At each weekly assessment, participants reported whether, over the past week, they had experienced any of 24 consequences using the B-YAACQ (Kahler et al., 2005). The B-YAACQ has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure, appropriate for longitudinal use, and is free of gender bias (Kahler et al., 2005, 2008). Example items (dichotomously scored) include, “I have felt very sick to my stomach or thrown up after drinking” and “I have woken up in an unexpected place after heavy drinking.” A weekly consequence outcome variable represented the total number of different consequences experienced over the past week. Across 10 weeks, Cronbach’s α’s for this measure, derived using tetrachoric correlations because of the dichotomous nature of the items, ranged from .90 to .95.

Readiness to change.

Participants reported their RTC weekly using The Contemplation Ladder, originally validated by Biener and Abrams (1991) to assess readiness to consider smoking cessation, and later applied by others for the assessment of RTC alcohol use (Barnett et al., 2006; Becker et al., 1996). The instructions for this measure read, “Each number listed below represents where a person might be in thinking about changing their drinking. Select the number that best represents where you are now.” Response options were from 0 to 10 and were displayed vertically (to signify a ladder). From top to bottom, anchors included the following: 10 (Taking action to change [e.g., cutting down]), 8 (Starting to think about how to change my drinking patterns), 5 (Think I should change, but not quite ready), 3 (Think I need to consider changing someday), and 0 (No thought of changing).

Data analytic plan

Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was used given our multiple weekly assessments and our goal of simultaneously examining both within-person and between-person influences on weekly drinking behavior (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). The data set was structured so that weekly alcohol use and consequence scores were lagged, allowing for the ability to use RTC scores from one week (“week t”) to predict alcohol use and consequences the following week (“week t + 1”), controlling for week t use/consequences the prior week. The person-period data set was represented by 960 survey points (96 participants x 10 weeks).

Analysis began with a screen for missing data and tests for violations of the assumptions of HLM. Square-root transformations were used to resolve nonnormality in the outcome variables, allowing us to specify our HLM models with normal (continuous) distributions. Residuals were normally distributed. In addition, we relied on robust standard errors for models with weekly drinks as the outcome, given a violation of the homogeneity of Level 1 variances assumption. Across a possible 960 points of data collection, 894 (93%) were completed. The average number of weekly surveys completed was 9.36 (SD = 1.67), and 89 participants (91%) completed at least seven weekly surveys.

Across models, within-person (Level 1) variables included RTC, alcohol use (either weekly drinks or HED frequency), and alcohol consequences; between-person (Level 2) variables included average RTC across the course of the study and gender. RTC scores at Level 1 were person-mean centered, such that scores represented how much higher or lower an individual’s RTC score was on a given week than his or her average readiness score across time; however, past-week behavior scores (drinking and/or consequences) were left uncentered because we were only interested in the pure autoregressive effect of those variables. RTC scores at Level 2 were sample-mean centered, and inclusion of this effect in all models offered the advantage of examining the influence of intraindividual variability in RTC (at Level 1) above and beyond a person’s tendency to report higher or lower RTC as compared with others in the sample. Analyses were conducted using the HLM 7.01 program (Raudenbush et al., 2013) with full maximum-likelihood estimation, and all intercept and slope effects were specified as random.

Multilevel analysis allows tests of mediation while still accounting for the clustered structure of the data (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001; MacKinnon, 2008). The multilevel test for mediation follows similar conceptual steps as in singlelevel, regression-based mediation models (Baron & Kenny, 1986) in that it involves an examination of the influence of (a) the independent variable on the dependent variable; (b) the independent variable on the mediator; (c) the mediator on the dependent variable, above and beyond the influence of the independent variable; and (d) a test of the significance of the mediated effect. Significance of the mediated effect was tested using the RMediation program (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011).

Results

Descriptives

Descriptive statistics for variables of interest for the full sample and separately by gender are presented in Table 1. The ICC for RTC was .74, indicating that 74% of the variability was between persons, whereas 26% was within persons across time. The ICCs for drinks per week, HED frequency, and consequences were .41, .28, and .50, respectively.

Table 1.

Sample descriptive statistics

| Variable | Full sample (N = 96) M (SD) | Men (n = 46) M (SD) | Women (n = 50) M (SD) | t | p |

| Drinks per week | 14.08 (11.28) | 18.85 (14.11) | 9.69 (4.77) | -4.19 | <.001 |

| Weekly HED frequency | 1.43 (0.95) | 1.65 (1.18) | 1.22 (0.61) | -2.22 | .03 |

| Alcohol consequences | 2.24 (1.74) | 2.24 (1.56) | 2.24 (1.91) | 0.02 | .99 |

| Readiness to change | 2.87 (2.78) | 2.98 (2.88) | 2.77 (2.71) | -0.37 | .71 |

Notes: Degrees of freedom for all t tests was 94; possible range on consequences was 0–24, but actual range at the weekly level was 0–13; possible and observed range on readiness to change at the weekly level was 0–10. HED = Heavy episodic drinking.

Substantive model results

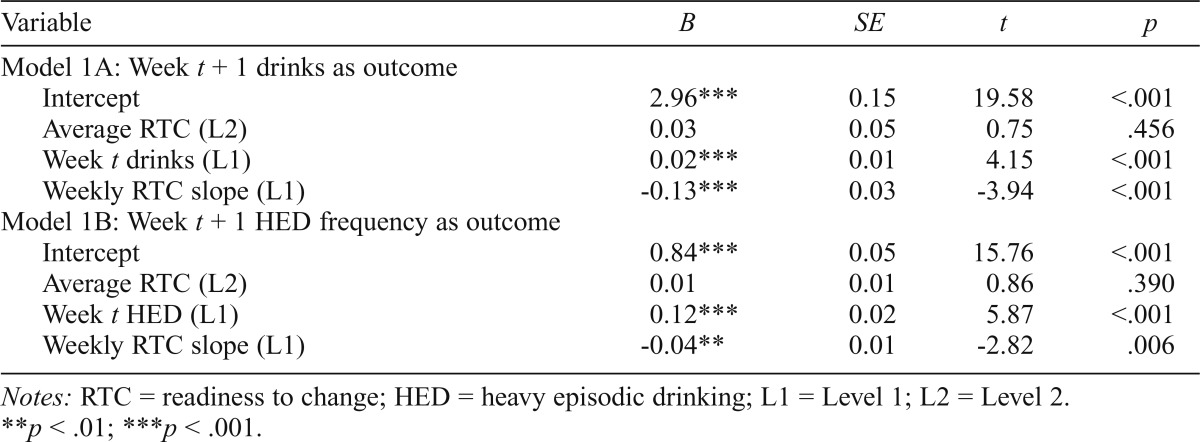

To test the hypothesis that intraindividual change in RTC would be negatively associated with subsequent alcohol use, Models 1A (drinks per week) and 1B (HED frequency) included week t RTC at Level 1 as a predictor variable of week t + 1 alcohol use. We controlled for the respective alcohol use measure during the prior week (week t, Level 1) and average RTC reported across the 10 weeks (Level 2). As hypothesized, we observed a negative association between RTC and subsequent-week alcohol use across both outcomes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hierarchical linear models examining associations between weekly readiness to change and subsequent alcohol use

| Variable | B | SE | t | p |

| Model 1A: Week t + 1 drinks as outcome | ||||

| Intercept | 2.96*** | 0.15 | 19.58 | <.001 |

| Average RTC (L2) | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.75 | .456 |

| Week t drinks (L1) | 0.02*** | 0.01 | 4.15 | <.001 |

| Weekly RTC slope (L1) | -0.13*** | 0.03 | -3.94 | <.001 |

| Model 1B: Week t + 1 HED frequency as outcome | ||||

| Intercept | 0 g4*** | 0.05 | 1 5.76 | <.001 |

| Average RTC (L2) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.86 | .390 |

| Week t HED (L1) | 0.12*** | 0.02 | 5.87 | <.001 |

| Weekly RTC slope (L1) | -0.04** | 0.01 | -2.82 | .006 |

Notes: RTC = readiness to change; HED = heavy episodic drinking; L1 = Level 1; L2 = Level 2.

p < .01;

p < .001.

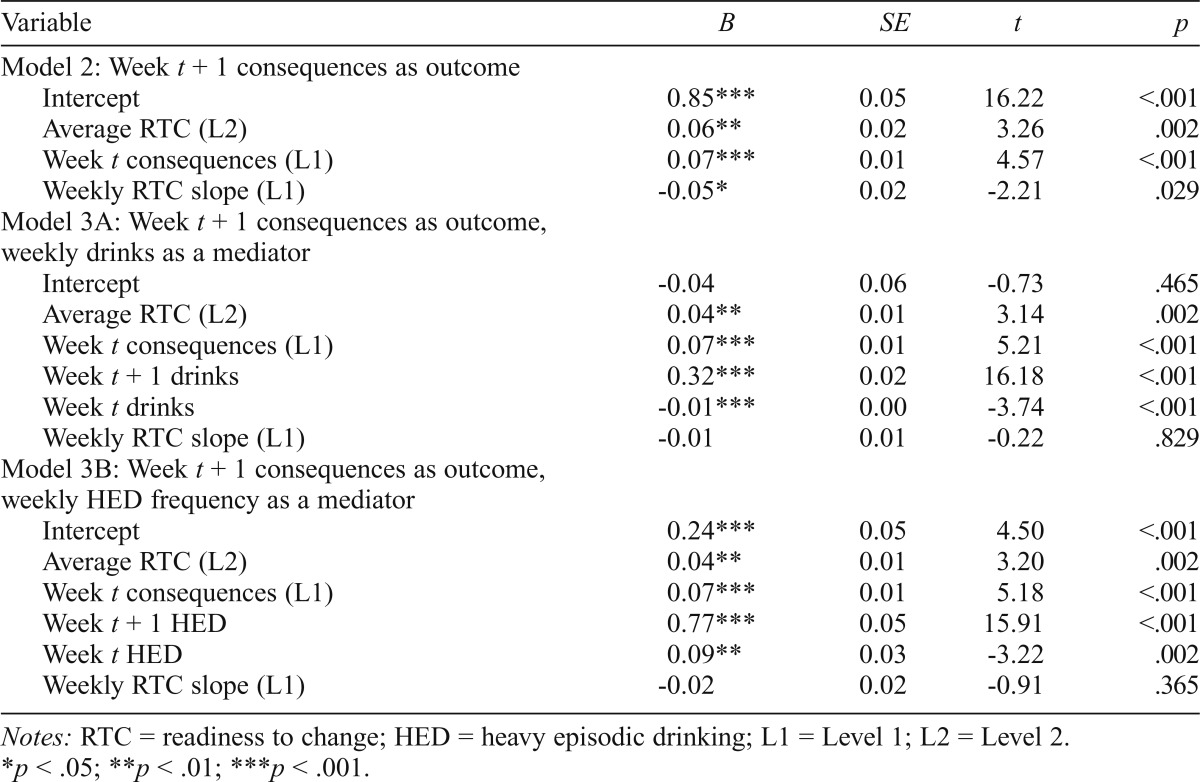

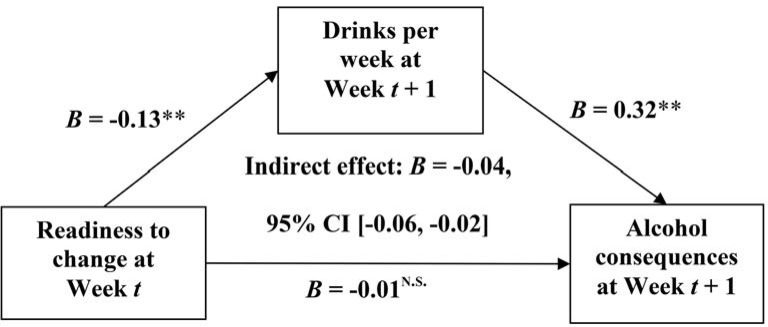

To test the hypothesis that intraindividual change in RTC would be negatively associated with subsequent alcohol consequences and that this association would be mediated by change in alcohol use, we tested three additional models. In Model 2 (Table 3, top), we tested the association between the independent variable (week t RTC) at Level 1 and the dependent variable (week t + 1 consequences). We controlled for week t consequences (Level 1) and average RTC reported across the 10 weeks (Level 2). As hypothesized, week t RTC was negatively associated with week t + 1 alcohol consequences, establishing the first step of mediation. The second step of mediation (i.e., testing whether the independent variable [RTC] is associated with the mediator [week t + 1 use]) was already established, as described above (Models 1A and 1B). Therefore, in Models 3A and 3B (Table 3, middle and bottom), we proceeded to test the relationship between the independent variable (RTC) at Level 1 and the dependent variable (week t + 1 consequences) when we controlledfor the mediator (week t + 1 drinks per week or HED frequency, respectively). Again, we also included autoregressive controls (for week t use and consequences) at Level 1 and average RTC at Level 2. In both models, the association between week t RTC and week t + 1 consequences did not remain statistically significant, whereas alcohol use at week t + 1 was significantly related to week t + 1 consequences. This satisfied the third step of the mediation test; once alcohol use was included in the models, the association between RTC and consequences was not observed. Finally, we tested the significance of the mediated associations and found that mediated effects were indeed statistically significant for both weekly drinks (B = -0.04, 95% CI [-0.06, -0.02]) and HED frequency (B = -0.03, 95% CI [-0.05, -0.02]). Thus, the association between RTC and subsequent change in alcohol consequences was fully mediated by change in alcohol use, as measured by either weekly drinks or HED frequency. Figure 1 depicts the mediational model for weekly drinks.

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear models examining associations between weekly readiness to change and alcohol consequences

| Variable | B | SE | t | p |

| Model 2: Week t + 1 consequences as outcome | ||||

| Intercept | 0.85*** | 0.05 | 16.22 | <.001 |

| Average RTC (L2) | 0.06** | 0.02 | 3.26 | .002 |

| Week t consequences (L1) | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 4.57 | <.001 |

| Weekly RTC slope (L1) | -0.05* | 0.02 | -2.21 | .029 |

| Model 3A: Week t + 1 consequences as outcome, weekly drinks as a mediator | ||||

| Intercept | -0.04 | 0.06 | -0.73 | .465 |

| Average RTC (L2) | 0.04** | 0.01 | 3.14 | .002 |

| Week t consequences (L1) | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 5.21 | <.001 |

| Week t + 1 drinks | 0.32*** | 0.02 | 16.18 | <.001 |

| Week t drinks | -0.01*** | 0.00 | -3.74 | <.001 |

| Weekly RTC slope (L1) | -0.01 | 0.01 | -0.22 | .829 |

| Model 3B: Week t + 1 consequences as outcome, weekly HED frequency as a mediator | ||||

| Intercept | 0.24*** | 0.05 | 4.50 | <.001 |

| Average RTC (L2) | 0.04** | 0.01 | 3.20 | .002 |

| Week t consequences (L1) | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 5.18 | <.001 |

| Week t + 1 HED | 0.77*** | 0.05 | 15.91 | <.001 |

| Week t HED | 0.09** | 0.03 | -3.22 | .002 |

| Weekly RTC slope (L1) | -0.02 | 0.02 | -0.91 | .365 |

Notes: RTC = readiness to change; HED = heavy episodic drinking; L1 = Level 1; L2 = Level 2.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Changes in alcohol use as a mediator between readiness to change at Week t and subsequent (Week t + 1) alcohol consequences. Although not shown in figure, alcohol use and alcohol consequences at Week t were included as covariates in the model. CI = confidence interval; n.s. = not significant. **p < .001.

Exploratory test of gender as a moderator

Next, we added an exploratory test of gender as a moderator of RTC effects in four of the above models, predicting weekly drinks (Model 1A), HED frequency (Model 1B), and consequences (Models 3A and 3B). Both the intercept (mean level) of the outcome and the slope of the association between RTC and the outcome were regressed on gender at Level 2 in all cases. The association between gender and the slope for the Level 1 association between RTC and drinking behavior was not significant in any of these models (ps > .05), suggesting that gender was not a significant moderator of the link between RTC and alcohol use or consequences. Not surprisingly, gender was a significant correlate of the intercepts of both weekly drinks (B = 0.80, SE = 0.23; t = 3.55, p < .001) and HED frequency (B = 0.16, SE = 0.07; t = 2.40, p = .02), with males reporting higher levels of both. However, there was no effect of gender on the intercept in the consequences model. In addition, all other associations, including the relationship between RTC and subsequent- week outcomes, remained consistent in these models with additional controls for gender; RTC was still associated with alcohol use at week t + 1 but not consequences once use was controlled.

Discussion

The present study advances the literature by examining the short-term predictive value of RTC when considering both alcohol use and alcohol consequences as outcomes, and how these associations may differ by gender. As hypothesized, we found that RTC one week was negatively associated with levels of drinking the following week, measured either as drinks per week or frequency of HED. Thus, increased RTC was prospectively related to decreased drinking. In addition, RTC one week was also negatively associated with subsequent consequences. In other words, behavior appeared to follow behavioral intentions—students who reported that they were considering making a change in their drinking behavior at a given time point did in fact tend to drink less at the next time point and, as a result, experienced fewer alcohol consequences. These negative associations between RTC and subsequent alcohol use and problems also imply that weeks when a student was relatively low on RTC tended to be followed by weeks characterized by higher levels of drinking and consequences.

The finding that changes in RTC were related in the expected direction to short-term changes in alcohol outcomes is consistent with the theoretical conceptualization of RTC as a dynamic construct (Prochaska et al., 1992) and supports the notion that natural ups and downs in RTC among young adult drinkers are proximally related to ups and downs in alcohol use and consequences. Although as noted, the literature on RTC and alcohol outcomes has yielded mixed findings, the present results are consistent with at least one past study that examined the association between intraindividual-level RTC and alcohol use over short intervals (i.e., 1 week) (Kaysen et al., 2009). Moreover, our study extends this prior work by measuring a range of outcome variables, demonstrating that RTC is associated with change in weekly alcohol use and frequency of HED, as well as alcohol consequences (as a function of reductions in alcohol use). Together, these findings suggest that RTC is indeed an important predictor of relatively proximal reductions in drinking behavior and associated negative consequences when these variables are studied as dynamic, fluid constructs (i.e., varying over time within individuals).

Moreover, we found that the association between RTC and subsequent alcohol consequences was fully mediated by changes in drinking behavior. This finding suggests that reductions in alcohol consumption are a primary means through which RTC may be linked to declines in alcohol consequences, rather than implementation of alternative protective behavioral strategies for reducing alcohol consequences without reducing drinking behavior (e.g., avoiding drinking games, using a designated driver; Pearson, 2013) that may have resulted in a direct association between RTC and consequences. However, conclusions regarding the potential role of other mediators of the association between RTC and subsequent alcohol consequences are tentative, given that other mediators were not explicitly tested in the present study. Thus, an important direction for future research is the simultaneous examination of several conceptually relevant mediators of change.

We also found that the link between RTC and later drinking behavior was similar for both male and female students. Although gender was associated with mean levels of alcohol use at the weekly level, it was unrelated to consequences. Moreover, we did not observe gender differences on RTC, nor did gender affect the extent to which RTC translated into actual behavioral change. The fact that some previous studies have reported interactions between gender and RTC in relation to drinking behavior (e.g., Foster, 2013) again highlights the issue of mixed findings in this literature, which could be a function of differences in study design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal). Notably, although we were adequately powered to detect fixed effects, we may have been underpowered to detect interactions. Therefore, conclusions about the similarity of observed effects across gender are tentative. Moreover, given that there has previously been a lack of studies examining gender with respect to proximal, within-person prospective associations between RTC and gender, more research is necessary to clarify the role of gender.

Although not the primary focus of this article, a few other interesting results emerged. First, our inclusion of average RTC at the between-persons level as a statistical control allowed us to reveal a discrepancy in the link between RTC and consequences, depending on the level of measurement. At the between-person level, reporting higher RTC on average across the course of the study was associated with higher levels of alcohol consequences. This is consistent with prior research demonstrating a similar association when looking at RTC as an individual difference factor in cross-sectional (Harris et al., 2008) and longitudinal studies (Collins et al., 2010). However, simultaneously modeling the within-person associations in this longitudinal study allowed us to see that, as described, higher levels of RTC at the intraindividual level were associated with lower levels of subsequent alcohol use and consequences (and vice versa). In other words, a student who tends to indicate higher RTC also tends to have more consequences; however, reporting higher RTC than one typically does on a given week is associated with shortterm alterations in one’s behavior. Such findings speak to the value of studying not only between-person predictors but also within-person predictors of drinking behavior. This work adds to the understanding of conflicting findings that characterize prior research relying on less complex designs.

Second, examination of ICCs revealed that 74% of the variability in RTC across weeks was attributable to differences between individuals, whereas 26% was due to within-person variability across time. Although this calculation is in part a function of the design (in this case, 10 occasions per person), this was very consistent with a study of female college drinkers (Kaysen et al., 2009) that demonstrated 72% of the variability was between persons. The present study extends this finding to both genders. Together, these two studies suggest that most of the difference in RTC is due to how people differ from one another. However, still a sizeable portion of variability was observed across time, suggesting that there is room to explain how and why students report differing levels of readiness across weeks. RTC is not necessarily a stable individual difference and can vary over even brief periods (from one week to the next). This may be due to ambivalence about changing and/or reflection on recent consequences. Regardless of the cause, this finding has implications for the measurement and action on RTC in clinical settings—students may be most amenable to intervention when their level of RTC is already high relative to their own typical level.

In terms of clinical implications, from this study we can infer that RTC is relevant not only for understanding naturalistic changes in alcohol consumption patterns but also for understanding naturalistic changes in the consequences that result from this consumption. From a harm-reduction perspective, this highlights the potential utility of targeting RTC with interventions geared toward reducing harms associated with drinking among college students. At the same time, the findings suggest that, because the link between RTC and subsequent declines in alcohol consequences was fully mediated by alcohol use, interventions that focus on RTC should not focus exclusively on alcohol consequences and instead should also focus on level of alcohol consumption.

The results should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. First, that our sample solely comprised regularly drinking junior and senior college students may limit the generalizability of findings. Learning processes that occur through the experience of consequences may differ in younger students or more novice drinkers; however, it is only among regular drinkers that we might expect to observe variability in RTC. Similarly, findings should not be generalized to older and/or alcohol-dependent populations. Important next steps in future research will be to replicate our findings with more heavily alcohol-involved populations and to examine whether and how the nature of change and ability to change varies depending on the level of alcohol involvement. Second, examining the link between RTC and consequences following treatment is an interesting future direction because it will allow us to understand whether changes in RTC that are a function of intervention (rather than naturalistic change) also translate into actual change in alcohol-related problems. In addition, it is possible that individuals who report higher RTC begin to implement protective behavioral strategies (Pearson, 2013), even if they continue to drink at similar levels. Assessment tools that measure readiness to reduce consequences (vs. just use) may be particularly well suited for such questions but have yet to be developed. Other work demonstrates the importance of confidence in the ability to change as a predictor of actual change in alcohol use (Bertholet et al., 2012). Future studies examining the role that this and perhaps other constructs play in predicting change in consequences above and beyond readiness, and the role they play in shorter term follow-ups (e.g., 1 week, as in the present study) are warranted.

Conclusions

This study found significant within-person associations between RTC and subsequent change in alcohol use, which in turn was associated with change in alcohol-related consequences. The findings extend prior research on RTC by examining these associations over more fine-grained (i.e., weekly) intervals and by focusing not only on alcohol use but also on consequences. The findings highlight important avenues for future research and suggest that RTC may be an important variable to target with respect to problematic drinking in college students. Intervention outcomes may be improved by intervening with heavy drinking college students at times during the naturally occurring change process when their RTC is highest.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01 DA018993 (to Jennifer P. Read) and grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31 AA018585), The Mark Diamond Research Fund of the Graduate student Association at the university at Buffalo, and training support (T32 AA007459, K01AA022938) to Jennifer E. Merrill.

References

- Barnett N. P., Goldstein A. L., Murphy J. G., Colby S. M., Monti P M. “I’ll never drink like that again”: Characteristics of alcohol-related incidents and predictors of motivation to change in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:754–763. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.754. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. M., Kenny D. A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker B., Maio R. F., Longabaugh R. One for the road: Current concepts and controversies in alcohol intoxication and injury research. Presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine; Denver, CO: 1996, May. [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet N., Gaume J., Faouzi M., Gmel G., Daeppen J. B. Predictive value of readiness, importance, and confidence in ability to change drinking and smoking. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:708–716. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-708. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L., Abrams D. B. The Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B., Murphy J. G., Carey K. B. Readiness to change in brief motivational interventions: A requisite condition for drinking reductions? Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:232–235. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.010. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira K. M., Kasperski S. J., Sharma E., Vincent K. B., O’Grady K. E., Wish E. D., Arria A. M. College students rarely seek help despite serious substance use problems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:368–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey K. B., Henson J. M., Carey M. P, Maisto S. A. Which heavy drinking college students benefit from a brief motivational intervention? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:663–669. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.663. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L., Parks G. A., Marlatt G. A. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. E., Logan D. E., Neighbors C. Which came first: The readiness or the change? Longitudinal relationships between readiness to change and drinking among college drinkers. Addiction. 2010;105:1899–1909. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03064.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Grant B. F., Stinson F. S., Chou P. S. Maturing out of alcohol dependence: The impact of transitional life events. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:195–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.195. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca F. K., Darkes J., Greenbaum P. E., Goldman M. S. Up close and personal: Temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster D. W. Readiness to change and gender: Moderators of the relationship between social desirability and college drinking. Journal of Alcoholism & Drug Dependence. 2013;2:141. doi: 10.4172/2329-6488.1000141. doi:10.4172/2329-6488.1000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T. R., Walters S. T., Leahy M. M. Readiness to change among a group of heavy-drinking college students: Correlates of readiness and a comparison of measures. Journal of American College Health. 2008;57:325–330. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.3.325-330. doi:10.3200/JACH.57.3.325-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R., Heeren T., Winter M., Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R. W., Zha W., Weitzman E. R. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. doi:10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. M., Sher K. J., Gotham H. J., Wood P K. Transitioning into and out of large-effect drinking in young adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:378–391. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.378. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.110.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler C. W., Hustad J., Barnett N. P, Strong D. R., Borsari B. Validation of the 30-day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. doi:10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler C. W., Strong D. R., Read J. P. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000171940.95813.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D. L., Lee C. M., LaBrie J. W., Tollison S. J. Readiness to change drinking behavior in female college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2009;16:106–114. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.106. doi:10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull J. L., MacKinnon D. P. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36:249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. doi:10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs J. L., Williams L. R., Lee C. M. Ups and downs of alcohol use among first-year college students: Number of drinks, heavy drinking, and stumble and pass out drinking days. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.005. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A. S., Faden V. B., Zucker R. A., Spear L. P. A developmental perspective on underage alcohol use. Alcohol Research & Health. 2009;32:3–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill J. E., Read J. P., Barnett N. P. The way one thinks affects the way one drinks: Subjective evaluations of alcohol consequences predict subsequent change in drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:42–51. doi: 10.1037/a0029898. doi:10.1037/a0029898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfai T. P., McNally A. M., Roy M. Volition and alcohol-risk reduction: The role of action orientation in the reduction of alcohol-related harm among college student drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:309–317. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00186-1. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. L., Grant C. Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson M. R. Use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies among college students: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:1025–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.006. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J. O., DiClemente C. C., Norcross J. C. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S. W., Bryk A. S. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.) Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S. W., Bryk A. S., Congdon R. HLM 7.01 for Windows [Computer software] Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S. W., Xiao-Feng L. Effects of study duration, frequency of observation, and sample size on power in studies of group differences in polynomial change. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:387–401. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J. P., Colder C. R., Merrill J. E., Ouimette P., White J., Swartout A. Trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms predict alcohol and other drug consequence trajectories in the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:426–439. doi: 10.1037/a0028210. doi:10.1037/a0028210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J. P., Merrill J. E., Kahler C. W., Strong D. R. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S. Readiness, importance, and confidence: Critical conditions of change in treatment. In: Miller W. R., Heather N., editors. Treating addictive behaviors (2nd ed., pp. 49–60) New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shealy A. E., Murphy J. G., Borsari B., Correia C. J. Predictors of motivation to change alcohol use among referred college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2358–2364. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.003. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D., MacKinnon D. P. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. doi:10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H., Nelson T. F. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. doi:10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]