Abstract

Background

Tick-borne rickettsioses are caused by obligate intracellular bacteria belonging to the spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsiae. Although Spotted Fever is prevalent in the Middle East, no reports for the presence of tick-borne pathogens are available or any studies on the epidemiology of this disease in the West Bank. We aimed to identify the circulating hard tick vectors and genetically characterize SFG Rickettsia species in ixodid ticks from the West Bank-Palestinian territories.

Methodology/Principal Findings

A total of 1,123 ixodid ticks belonging to eight species (Haemaphysalis parva, Haemaphysalis adleri, Rhipicephalus turanicus, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, Rhipicephalus bursa, Hyalomma dromedarii, Hyalomma aegyptium and Hyalomma impeltatum) were collected from goats, sheep, camels, dogs, a wolf, a horse and a tortoise in different localities throughout the West Bank during the period of January-April, 2014. A total of 867 ticks were screened for the presence of rickettsiae by PCR targeting a partial sequence of the ompA gene followed by sequence analysis. Two additional genes, 17 kDa and 16SrRNA were also targeted for further characterization of the detected Rickettsia species. Rickettsial DNA was detected in 148 out of the 867 (17%) tested ticks. The infection rates in Rh. turanicus, Rh. sanguineus, H. adleri, H. parva, H. dromedarii, and H. impeltatum ticks were 41.7, 11.6, 16.7, 16.2, 11.8 and 20%, respectively. None of the ticks, belonging to the species Rh. bursa and H. aegyptium, were infected. Four SFG rickettsiae were identified: Rickettsia massiliae, Rickettsia africae, Candidatus Rickettsia barbariae and Candidatus Rickettsia goldwasserii.

Significance

The results of this study demonstrate the geographic distribution of SFG rickettsiae and clearly indicate the presence of at least four of them in collected ticks. Palestinian clinicians should be aware of emerging tick-borne diseases in the West Bank, particularly infections due to R. massiliae and R. africae.

Author Summary

Tick borne rickettsial diseases may have similar clinical characteristics, yet epidemiologically and etiologically different diseases. To date, no studies have been conducted to detect potential tick vectors of rickettsiae in the West Bank. Therefore, we aimed to identify tick species and to determine the presence of Rickettsia pathogens in naturally infected ixodid ticks. The overall prevalence of SFG rickettsiae detected in ixodid ticks in nine Palestinian districts was 17%. Our results document for the first time the finding of two important human pathogens carried by ixodid ticks in the West Bank: R. massiliae and R. africae, the agent of African tick bite fever. Genetically, the detected Rickettsia spp. clustered into 3 different groups: R. massiliae, C. R. barbariae and C. R. goldwasserii. Most of Rickettsia-infected ticks were collected from dogs, camels and sheep, increasing the risk of transmitting rickettsial infections to animal owners, shepherds and farmers. These findings highlight the importance of hard ticks and their potential hazard for human health in the West Bank.

Introduction

Tick-borne spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsioses are caused by obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the genus Rickettsia [1]. Feeding ticks can transmit these microorganisms to humans and animals. Various vertebrates are suspected to serve as reservoirs for Rickettsia species; however, some are susceptible to rickettsial infections and may develop rickettsemia following tick bite [2]. The human disease may present as a fever with clinical symptoms including headache, rash, and occasional eschar formation at the site of the tick bites [3].

Mediterranean spotted fever (MSF), caused by Rickettsia conorii, is transmitted by the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, which is well adapted to urban environments. Previous studies in Israel have documented the presence of two spotted -fever group (SFG) rickettsiae: the tick-borne rickettsia, Rickettsia conorii israelensis and the flea-borne rickettsia, Rickettsia felis [4], [5]. Rickettsia conorii israelensis has been described in Tunisia, Libya, Sardinia-Italy, and Portugal [6]. Furthermore, a number of other SFG pathogenic rickettsiae including Rickettsia africae, Rickettsia massiliae and Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae have been detected in ticks from Israel in addition to some rickettsial species such as Candidatus Rickettsia barbariae and Candidatus Rickettsia goldwasserii which were not associated with diseases, to date [7], [8], [9].

The number of newly described SFG rickettsiae has increased in recent decades [4]. Sequence analysis of PCR-amplified fragments targeting genes encoding the citrate synthase (gltA) [10], Rickettsia-specific outer membrane protein (ompA) [11], the 17kDa lipoprotein precursor antigen gene (17 kDa) [12], and the ribosomal 16S rRNA gene [13] has become a reliable method for the identification of Rickettsia species. Molecular typing of infectious agents is important for better understanding of ecological niches and identifying circulating strains and their virulence. Although various Rickettsia species are found in ticks from Israel; to date, no entomological survey has been carried out in the West Bank, and no clinical data or reports for the presence of tick-borne pathogens are available. Thus, this study aimed at identification of the circulating hard tick vectors and Rickettsia species in naturally infected ixodid ticks collected from the West Bank, using PCR and sequence analysis with special focus on their potential threat for humans and animals.

Materials and Methods

Study area and ticks

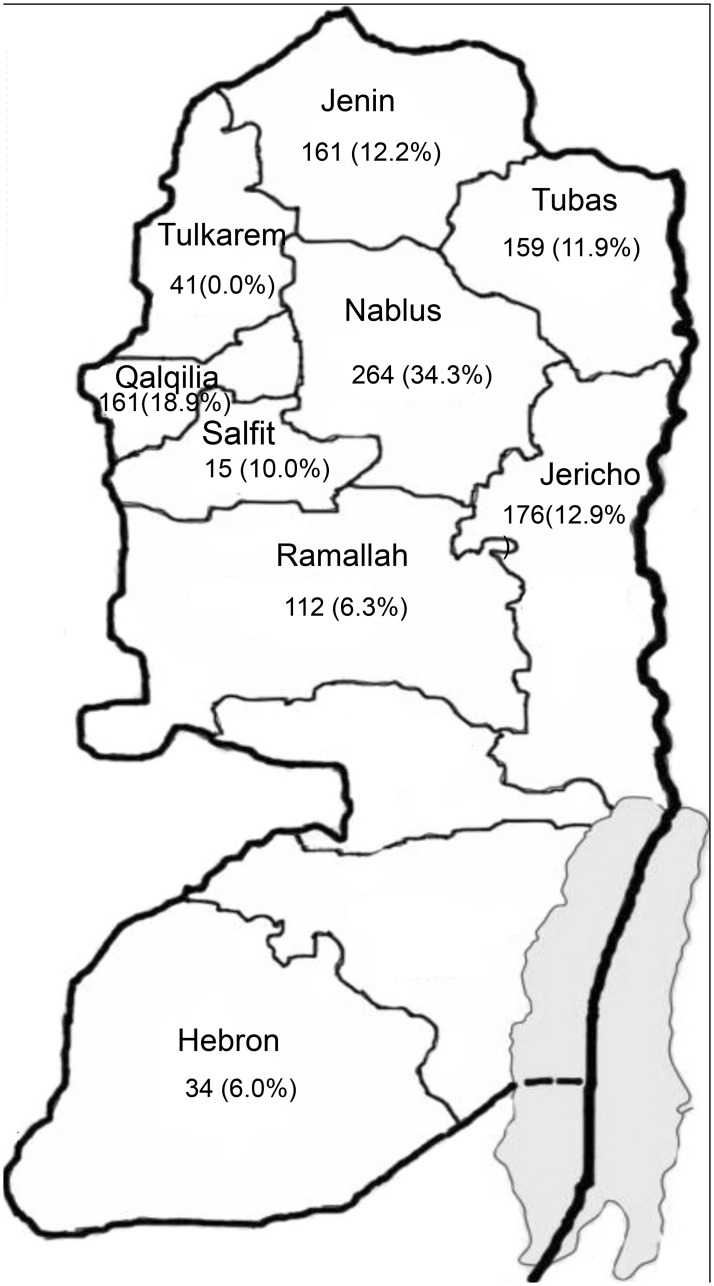

To identify the circulating hard ticks in the West Bank and to evaluate the presence of rickettsial infection in these ticks, one to ten hard ticks per animal host, for a total of 1,123, were collected during January to April, 2014 from dogs, camels, sheep, a horse, a wolf, and a tortoise residing in nine districts in the West Bank. The districts are located in three zones in the central, northern and southern regions of the country (Fig 1). All ticks were gently removed from their hosting animals by forceps or hand, and individually placed into small, labeled plastic tubes containing 70% ethanol for morphological identification. The ticks were identified using standard taxonomic keys [14], [15], [16], [17] and stored at −20°C until DNA extraction.

Fig 1. Distribution of ticks in the West Bank-Palestinian territories from which rickettsial DNA was detected.

Percentage indicates the overall infection rate of tick populations in each district.

DNA extraction

A maximum of five ticks of different tick species per hosting animal were randomly selected for DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was individually extracted from a total of 867 tick samples. Prior DNA extraction, individual ticks were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), air dried for 10 min on tissue paper and separately sliced into small pieces by a sterile scalpel blade then manually homogenized with a sterile micro pestle, resuspended in 200 μl of lysis buffer and 20 μl of proteinase K. After overnight incubation at 56°C with a continuous gentle shaking, the DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA tissue extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's protocol. Purified DNA was stored at 4°C until use. Three μl of template DNA (approximately 100–200 ng per tick) were used for each PCR.

Molecular detection of Rickettsia species

Screening for the presence of rickettsial DNA was carried out by conventional PCR targeting a 250-bp fragment of the ompA gene using 107F and Rm299 primers as described previously [7] with the following modification: final volume of 25μl using PCR-Ready Supreme mix (Syntezza Bioscience, Jerusalem) including primers at 1μM final concentration. Positive samples were further characterized targeting a 426-bp portion of the 16SrRNA and a 265-bp portion of the 17kDa protein gene as previously described [18], [19]. For Rickettsia species identification, strong positive samples were sent for sequencing. DNA extract of the first ompA positive sample, identified as R. massiliae, by direct sequencing, was used as a positive control and ultra pure water were used as a negative control in each amplification reaction.

Phylogenetic analysis

DNA sequences of the positive PCR products were assembled using Bioedit software, used in a BLAST search (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) and aligned with sequences of other rickettsial species registered in the GenBank. To infer relationships between the obtained amplicons and other reference sequences published in GenBank, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA6 program.

Statistical tests

Statistical analysis was done using the SPSS program v20. Two –tailed t- test and Pearson’s correlation were performed. P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

The animal population was residing in different farms throughout the West Bank. Prior to ticks sampling, the animal owners were verbally informed about the goals of the project and the sampling protocol. All owners gave their verbal informed consent to collect ticks from their animals. The study was approved by the ethics committee at the Faculty of Medicine in Al-Quds University-Palestine (EC number: ZA/196/013).

Results

Sampling and identification of ticks

A total of 1,123 hard ticks were collected from 320 animals (234 dogs, 68 sheep, 10 camels, 5 goats, one horse, one wolf and one Mediterranean spur-thighed tortoise). From each infested animal one to ten ticks were collected. Of them, 547 were male ticks (48.7%), 511 females (45.5%) and 65 nymphs (5.8%). All tick samples were identified to the species level as follows: Rhipicephalus sanguineus (n = 694), Rhipicephalus turanicus (n = 191), Rhipicephalus bursa (n = 16), Rhipicephalus spp. (n = 21), Haemaphysalis parva (n = 100), Haemaphysalis adleri (n = 20), Hyalomma dromedarii (n = 68), Hyalomma impeltatum (n = 5), Hyalomma aegyptium (n = 4), and Hyalomma spp. (n = 4) (Table 1).

Table 1. Morphological identification of the collected ticks and their associated host animal species.

| Animal species | Tick species (number) | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Dog | Rh. sanguineus (634), Rh. turanicus (53), Rh. bursa (1), Rh. spp.(15), H. parva (93), H. adleri (19) | 518 |

| Sheep | Rh. turanicus (138), Rh. sanguineus (41), Rh. bursa (14), Rh. spp.(6), H. parva (4), H. adleri (1) | 204 |

| Camel | H. dromedarii (68), H. impeltatum (5), Hyalomma spp. (4). | 77 |

| Goat | Rh. sanguineus (16), Rh. bursa (1), H. parva (3) | 20 |

| Horse | Rh. sanguineus (2) | 2 |

| Tortoise | H. aegyptium (4) | 4 |

| Dead wolf | Rh. sanguineus (1) | 1 |

| Total | Rh. sanguineus (694), Rh. turanicus (191), Rh.spp.(21), Rh. bursa (16), H. parva (100), H. adleri (20), H. dromedarii (68), H. impeltatum (5), Hyalomma spp. (4), H. aegyptium (4), | 1123 |

Screening of ticks for rickettsial DNA

A set of 867 ticks comprising eight different species were screened for rickettsial DNA targeting Rickettsia–specific ompA (Table 2). A sample was considered positive when PCR yielded a fragment with the expected length (250 bp) of the ompA rickettsial gene. The overall prevalence of rickettsiae infection was 17% (148/867) in all ticks (Table 2). The detection of rickettsial DNA was significantly higher in female ticks (20.4%) than in male (15.7%) and nymph ticks (4.8%, p<0.01). The overall prevalence of rickettsial DNA was markedly higher in ticks collected from Nablus (34.3%; 66/192) compared to other districts (p<0.01) (Fig 1).

Table 2. The overall prevalence of Rickettsial DNA and molecular identification of SFG Rickettsia in tick species picked from different hosts from different districts in the West Bank-Palestinian territories.

| Ectoparasites | #PCR Positives (%) | Animal host | Collection site | Ricketssia sp. detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh. turanicus | 60(41.7) | Dog, Sheep | Jericho, Nablus, Qalqilia, Tubas, Ramallah | R. massiliae, C. R.barbariae, C.R. goldwasserii |

| Rh. sanguineus | 61(11.6) | Dog, Sheep, Goat, Horse, wolf | Jericho, Nablus, Jenin,Qalqilia, Tubas, Ramallah | R. massiliae, C. R.barbariae, C.R. goldwasserii |

| Rh. spp. | 3(15.8) | Dog, Sheep | Nablus | Rickettsia spp. |

| H. adleri | 3(16.7) | Dog, Sheep | Jenin,Qalqilia, | R. massiliae, C.R. goldwasserii |

| H. parva | 11(16.2) | Dog, Sheep | Nablus, Jenin,Qalqilia, Ramallah | R. massiliae, C.R. goldwasserii |

| H. dromedarii | 8(11.8) | Camel | Jericho | R. africae, C. R. barbariae |

| H. impeltatum | 1(20) | Camel | Jericho | R. africae |

| Hyalomma spp. | 1(25) | Camel | Jericho | Rickettsia spp. |

| Total ticks | 148 (17) |

The infection rates in Rh. turanicus, Rh. sanguineus, Haemaphysalis adleri, H. parva, Hyalomma dromedarii and H. impeltatum ticks were 41.7, 11.6, 16.7, 16.2, 11.8 and 20% respectively. None of the ticks belonging to Rh. bursa (0/13) and H. aegyptium (0/4), taken from sheep and one tortoise, respectively, were infected (Table 2).

Identification of the Rickesttia species

Among the positive samples (n = 148), identification of rickettsial DNA based on sequencing of the ompA amplicons were successfully obtained from 63 (42.6%) samples which showed strong bands on agarose gel. These samples were subsequently subjected to two additional amplification reactions targeting the 16SrRNA and 17kDa genes of Rickettsia species. Successful sequences were only obtained from (35/63) and (36/63) by 16SrRNA and 17kDa PCR, respectively.

BLAST analysis of the positive ompA sequences revealed 4 different rickettsial species. Twenty eight ticks were tested positive for R. massiliae-DNA including 15 Rh. turanicus, 11 Rh. sanguineus, one Haemaphysalis parva and one H. adleri, all obtained from dogs and sheep. C. R. barbariae-DNA was found in 12 ticks: 5 Rh. turanicus, 3 Rh. sanguineus and 4 H. dromedarii. The DNA of C. R. goldwasesrii- was detected in 17 ticks: 2 Rh. turanicus, 7 Rh. sanguineus, 6 H. parva and 2 H. adleri. Four ticks were positive for Rickettsia species found in four Rh. sanguineus ticks, Furthermore, R. africae-DNA was detected in two ticks, H. impeltatum and H. dromedarii obtained from two different camels in Jericho (Fig 2A). There were no cases in which multiple rickettsiae species were detected in the same infected tick.

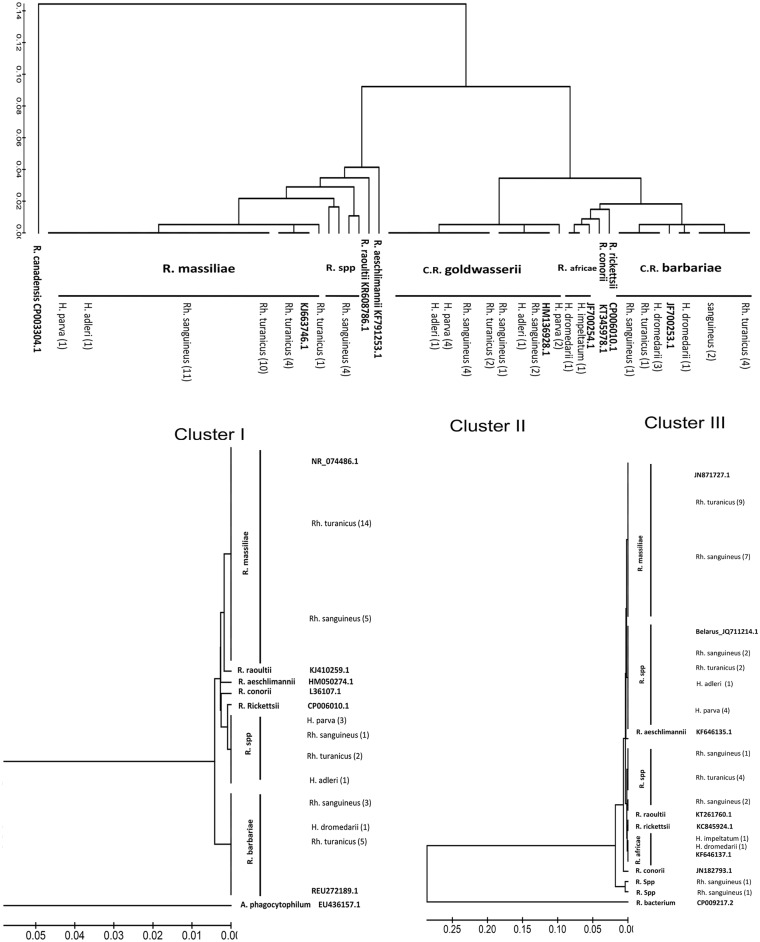

Fig 2. Phylogenetic analyses of Rickettsia species detected in the West Bank-Palestinian territories based on partial sequences of ompA, 16SrRNA and 17kDa genes.

MEGA 6.0 program was used for constructing the Phylogenetic trees. DNA sequences were aligned using ClustalW (1.6) program, the trees were built using UPGMA statistical method with 1000 bootstrap using maximum composite likelihood model, comparing panels: (A) 217 bp OmpA (B) 371 bp 16SrRNA (C) 248 bp 17kDa DNA Rickettsia sequences from ticks collected in this study to the respective Rickettsia reference sequences deposited in the NCBI GenBank. R. canadensis (CP003304.1), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (EU436157.1) and R. bacterium (CP009217.2) was used as out-groups. Species of ticks and the number of identical sequences from the same tick species was indicated. All sequences identified in this study were derived from the West Bank.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis based on ompA sequences revealed three main clusters: R. massiliae, C. R. barbariae and C. R. goldwasserii. Cluster I, representing the R. massiliae group (n = 28). In this cluster, the nucleotide ompA sequences of R. massiliae identified in this study were identical to each other and to the respective R. massiliae reference sequence (accession no. KJ663746.1) deposited in the NCBI GenBank (Fig 2A). The same samples also showed one cluster and had 100% similarity to the R. massiliae reference strains (NR074486.1 and JN871727.1) based on the 16sRNA and 17kDa analysis, respectively (Fig 2B and 2C). The DNA sequence of Rickettsia canadensis (CP003304.1) that do not belong to the SFG [20], was used as an out group in the analysis of ompA gene while the sequences of Anaplasma phagocytophilum (EU 436157.1) and Rickettsiaceae bacterium (CP009217.2) were used as out groups in the analyses of the 16SrRNA and 17kDa genes, respectively. On the basis of the ompA sequences, DNA sequences of four amplicons (1.4G, 1.4H, 14.8 A, 14.8 B) had several nucleotide differences and showed 96–98% sequence identity to the ompA sequences of R. massiliae identified in this study and to the reference strain of R. massiliae (KJ663746.1). These samples showed 92% and 89% sequence identity to the ompA sequences of the reference strain sequences of R. aeschlimannii (KF791253.1) and R. raoultii (KR608786.1), respectively. The four samples were further characterized by 17kDa and 16S rRNA genes, the partial 17kDa gene sequence of these samples revealed 94% and 93% similarity to the reference strain sequences of R. raoultii (KT261760.1) and R. conorii (JN182793.1), respectively. Two of them (14.84A and 14.8B) formed a separate branch with in this group complicating the further confirmation of this Rickettsia spp. (Fig 2C). However, none of these samples (n = 4) were successfully sequenced based on 16SrRNA gene.

Cluster II represents the C. R. goldwasserii group. The ompA sequences had 100% similarity to the C. R. goldwasserii reference sequence (HM136928.1) whilst the 17kDa sequences of the same samples had 100% similarity to the corresponding sequence of an incompletely described Rickettsia sp. Belarus (JQ711214.1) (Fig 2C). The 16SrRNA sequences showed 99% similarity to that of R. rickettsii (NR103923). Cluster III represents the C. R. barbariae group; the ompA and 16SrRNA sequences had 100% similarity to the Candidatus Rickettsia barbariae reference sequences (JF700253.1 and EU272189.1), respectively (Fig 2A and 2B). When 17kDa sequences were obtained from the same samples, they showed 99% sequence similarity to the homologous fragments of R. raoultii (KT261760.1) and to the other unidentified Rickettsia sp. (KM386654.1) as revealed by BLAST analysis.

A sub-cluster of two ompA sequences was identified as R. africae and showed 100% sequence similarity with a homologous fragment of R. africae (JF700254) detected in Hyalomma detritum from the Golan Heights [9]. The 17kDa sequences of these two samples had also 100% nucleotide identity to that of R. africae (KF646137.1) but they were not detected by the 16S rRNA PCR.

Discussion

The overall prevalence of SFG rickettsiae detected in ixodid ticks in nine Palestinian districts was 17%. Ticks detected in this study belonged to three genera (Rhipicephalus, Haemaphysalis and Hyalomma) and collected from different host animals. The findings of this study highlight the importance of hard ticks for human health in the West Bank. Rhipicephalus sanguineus was the most prevalent tick species found in this study. It parasitized a wide range of mammals including dogs, sheep, goats and horses; however the main vector for SFG rickettsiae detected in this study was Rh. turanicus. Our results document the detection of two important human pathogens in ticks from the West Bank, R. massiliae and R. africae. R. massiliae was the most prevalent rickettsial species detected in this study. This pathogen was first isolated from Rh. sanguineus in Marseille in 1992 [21], and since then it has been detected in ticks within the genus Rhipicephalus in Greece, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Sardinia (Italy), Morocco and Israel [22], [23], [4], [24], [25], [7]. The first isolation of R. massiliae was reported from a human patient in Sicily in 1985 and identified in 2005 [26]. The clinical presentation of R. massiliae infection has been previously described [23],[27],[28]. Common clinical signs include fever, night sweats, headache, maculopapular rash and necrotic eschar at the tick bite site. In agreement with other studies, all ticks infected with this pathogen in this study belonged to the genus Rhipicephalus except for two which belonged to the genus Haemaphysalis obtained from the same dog in Jenin district. However, detection of R. massiliae in Haemaphysalis punctata ticks was previously reported in southeast England [29].

In this study, most of R. massiliae- infected ticks were removed from dogs (77%) and to a lesser extent from sheep (23%), increasing the risk of transmitting rickettsial infections to the animal owners, i. e. dog owners, shepherds and farmers. The phylogenetic tree based on partial DNA sequences of ompA, 16SrRNA and 17 kDa showed higher genetic variability among the R. massiliae strains using ompA gene than 16SrRNA and 17 kDa loci. The second SFG pathogenic Rickettsia found in this study was R. africae, the agent of African tick bite fever. The detection of R. africae, in Hyalomma spp. collected from camels in the West Bank confirms the results of a previous report associating R. africae with Hyalomma ticks in Egypt and Israel [30], [8], [9]. Livestock movements and migratory birds may play a role in the geographic spread of R. africae [31]. We observed a strong geographic correlation between the overall prevalence of rickettsial DNA in ticks collected from Nablus (Northern district) compared to the prevalence of infected ticks collected from other districts in the north, Ramallah (centre) and Hebron (south). Future studies with high representative number of ticks are required to address the comparative importance of geographic distribution on the infection rate of these ticks in the West Bank.

Candidatus. R. goldwasserii was also detected in Rhipicephalus ticks collected from dogs in the northern region of the West Bank. This Rickettsia was first detected in two Haemaphysalis ticks (H. adleri and H. parva) from golden jackals in Israel. Phylogenetic analysis based on concatenated four gene fragments (gltA-ompA-sca4-ompB) indicated that the nucleotide sequences of these SFG rickettsiae belonged to a novel phylogenetic lineage related to C. R. siciliensis detected in Rh. turanicus ticks. [32]. In the present study, the identification of C. R. goldwasserii in Rh. sanguineus and Rh. turanicus, in addition to the already known Haemaphysalis spp, expands the current knowledge concerning tick species that host C. R. goldwasserii in our region. Based on ompA phylogeny, high genetic homology was observed among the C. R. goldwasserii group identified in this study. However, these samples were found to be 100% similar to the corresponding sequence of a not well characterized Rickettsia sp. Belarus and 99% similar to that of R. rickettsii based on 17kDa and 16srRNA respectively. Thus, for a more accurate classification of this uncultivated SFG Rickettsia, further testing and phylogenetic analysis with additional genes is needed since no sequences of these two latter genes of C. R. goldwasserii were available in the GenBank.

This is the first study to report the presence of C. R. barbariae in 9.6% of Hyalomma ticks in the West Bank. The presence of C. R. barbariae has been previously reported in several Rhipicephalus spp. in Portugal, Italy, France, Cyprus and later in Rhipicephalus ticks flagged from the vegetation in Israel [24],[33],[2], [9]. However, no ompA sequence differences were observed in C. R. barbariae DNA detected in Hyalomma or Rhipicephalus ticks collected from camels, dogs and sheep residing in different localities throughout the West Bank. In conclusion, the findings presented in this study provide evidence for the presence of R. massiliae and R. africae in different ixodid ticks collected from various regions in the West Bank. In addition to Rhipicephalus species, members of the genus Hyalomma and Haemaphysalis may also play an important role in the epidemiology of SFG Rickettsia spp. Clinicians in the West Bank and neighboring countries should consider a range of SFG diseases in the differential diagnoses of patients present with fever of unknown origin and clinical signs compatible with rickettsioses.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Hague, The Netherlands and NVHU under grant reference number 2014.52146 and USAID grant MERC TA-MOU-12-M32-038. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Azad AF, Beard CB (1998) Rickettsial pathogens and their arthropod vectors. Emerg Infect Dis 4: 179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chochlakis D, Ioannou I, Sandalakis V, Dimitriou T, Kassinis N, et al. (2012) Spotted fever group Rickettsiae in ticks in Cyprus. Microb Ecol 63: 314–323. 10.1007/s00248-011-9926-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouqui P, Bacellar F, Baranton G, Birtles RJ, Bjoersdorff A, et al. (2004) Guidelines for the diagnosis of tick-borne bacterial diseases in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 10: 1108–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parola P, Paddock CD, Raoult D (2005) Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts. Clin Microbiol Rev 18: 719–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer O, Baneth G, Eshkol T, Shaw SE, Harrus S (2006) Polygenic detection of Rickettsia felis in cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis) from Israel. Am J Trop Med Hyg 74: 444–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parola P, Paddock CD, Socolovschi C, Labruna MB, Mediannikov O, et al. (2013) Update on tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: a geographic approach. Clin Microbiol Rev 26: 657–702. 10.1128/CMR.00032-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrus S, Perlman-Avrahami A, Mumcuoglu KY, Morick D, Baneth G (2011) Molecular detection of Rickettsia massiliae, Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae and Rickettsia conorii israelensis in ticks from Israel. Clin Microbiol Infect 17: 176–180. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinerman G, Baneth G, Mumcuoglu KY, van Straten M, Berlin D, et al. (2013) Molecular detection of Rickettsia africae, Rickettsia aeschlimannii, and Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae in camels and Hyalomma spp. ticks from Israel. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 13: 851–856. 10.1089/vbz.2013.1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waner T, Keysary A, Eremeeva ME, Din AB, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. (2014) Rickettsia africae and Candidatus Rickettsia barbariae in ticks in Israel. Am J Trop Med Hyg 90: 920–922. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roux V, Rydkina E, Eremeeva M, Raoult D (1997) Citrate synthase gene comparison, a new tool for phylogenetic analysis, and its application for the rickettsiae. Int J Syst Bacteriol 47: 252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roux V, Fournier PE, Raoult D (1996) Differentiation of spotted fever group rickettsiae by sequencing and analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphism of PCR-amplified DNA of the gene encoding the protein rOmpA. J Clin Microbiol 34: 2058–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chmielewski T, Podsiadly E, Karbowiak G, Tylewska-Wierzbanowska S (2009) Rickettsia spp. in ticks, Poland. Emerg Infect Dis 15: 486–488. 10.3201/eid1503.080711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roux V, Raoult D (1995) Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Rickettsia by 16S rDNA sequencing. Res Microbiol 146: 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman-Muhsam B (1951) A Note on East Mediterranean Species of the Haemaphysalis. Bull Res Counc Isr 1: 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman-Muhsam B (1954) Revision of the genus Hyalomma. Bull Res Counc Isr 64: 70–150. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pegram R, Clifford C, Walker J, Keirans J (1987) Clarification of the Rhipicephalus sanguineus Group (Acari, Ixodoidea, Ixodidae). I. R. sulcatus Neumann, 1908 and R. turanicus Pomerantsev, 1936. Syst Parasitol 10: 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apanaskevich DA, Schuster AL, Horak IG (2008) The genus Hyalomma: VII. Redescription of all parasitic stages of H. (Euhyalomma) dromedarii and H. (E.) schulzei (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol 45: 817–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogo NI, de Mera IG, Galindo RC, Okubanjo OO, Inuwa HM, et al. (2012) Molecular identification of tick-borne pathogens in Nigerian ticks. Vet Parasitol 187: 572–577. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, Zaki SR, Goldsmith CS, et al. (2004) Rickettsia parkeri: a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 38: 805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anstead CA, Chilton NB (2013) A novel Rickettsia species detected in Vole Ticks (Ixodes angustus) from Western Canada. Appl Environ Microbiol 79: 7583–7589. 10.1128/AEM.02286-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beati L, Raoult D (1993) Rickettsia massiliae sp. nov., a new spotted fever group Rickettsia. Int J Syst Bacteriol 43: 839–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babalis T, Tselentis Y, Roux V, Psaroulaki A, Raoult D (1994) Isolation and identification of a rickettsial strain related to Rickettsia massiliae in Greek ticks. Am J Trop Med Hyg 50: 365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardenosa N, Segura F, Raoult D (2003) Serosurvey among Mediterranean spotted fever patients of a new spotted fever group rickettsial strain (Bar29). Eur J Epidemiol 18: 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mura A, Masala G, Tola S, Satta G, Fois F, et al. (2008) First direct detection of rickettsial pathogens and a new rickettsia, 'Candidatus Rickettsia barbariae', in ticks from Sardinia, Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect 14: 1028–1033. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarih M, Socolovschi C, Boudebouch N, Hassar M, Raoult D, et al. (2008) Spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks, Morocco. Emerg Infect Dis 14: 1067–1073. 10.3201/eid1407.070096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vitale G, Mansuelo S, Rolain JM, Raoult D (2006) Rickettsia massiliae human isolation. Emerg Infect Dis 12: 174–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parola P, Socolovschi C, Jeanjean L, Bitam I, Fournier PE, et al. (2008) Warmer weather linked to tick attack and emergence of severe rickettsioses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2: e338 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Garcia JC, Portillo A, Nunez MJ, Santibanez S, Castro B, et al. (2010) A patient from Argentina infected with Rickettsia massiliae. Am J Trop Med Hyg 82: 691–692. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tijsse-Klasen E, Hansford KM, Jahfari S, Phipps P, Sprong H, et al. (2013) Spotted fever group rickettsiae in Dermacentor reticulatus and Haemaphysalis punctata ticks in the UK. Parasit Vectors 6: 212 10.1186/1756-3305-6-212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdel-Shafy S, Allam NA, Mediannikov O, Parola P, Raoult D (2012) Molecular detection of spotted fever group rickettsiae associated with ixodid ticks in Egypt. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 12: 346–359. 10.1089/vbz.2010.0241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palomar AM, Santibanez P, Mazuelas D, Roncero L, Santibanez S, et al. (2012) Role of birds in dispersal of etiologic agents of tick-borne zoonoses, Spain, 2009. Emerg Infect Dis 18: 1188–1191. 10.3201/eid1807.111777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keysary A, Eremeeva ME, Leitner M, Din AB, Wikswo ME, et al. (2011) Spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks collected from wild animals in Israel. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85: 919–923. 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Socolovschi C, Reynaud P, Kernif T, Raoult D, Parola P (2012) Rickettsiae of spotted fever group, Borrelia valaisiana, and Coxiella burnetii in ticks on passerine birds and mammals from the Camargue in the south of France. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 3: 355–360. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.