Abstract

Learning to distinguish nonnative words that differ in a critical phonetic feature can be difficult. Speech training studies typically employ methods that explicitly direct the learner's attention to the relevant nonnative feature to be learned. However, studies on vision have demonstrated that perceptual learning may occur implicitly, by exposing learners to stimulus features, even if they are irrelevant to the task, and it has recently been suggested that this task-irrelevant perceptual learning framework also applies to speech. In this study, subjects took part in a seven-day training regimen to learn to distinguish one of two nonnative features, namely, voice onset time or lexical tone, using explicit training methods consistent with most speech training studies. Critically, half of the subjects were exposed to stimuli that varied not only in the relevant feature, but in the irrelevant feature as well. The results showed that subjects who were trained with stimuli that varied in the relevant feature and held the irrelevant feature constant achieved the best learning outcomes. Varying both features hindered learning and generalization to new stimuli.

I. INTRODUCTION

Adults commonly encounter difficulty when learning to distinguish nonnative speech sounds. This difficulty is typically attributed to interference from the native language phonology, that is, knowledge of native speech sound categories. Whereas native speech perception abilities develop spontaneously following exposure to the ambient language in early life (Kuhl et al., 1992; Werker and Tees, 1984), learning to perceive a nonnative language is quite effortful and is thought to require explicit instruction (Bradlow, 2008). A large amount of literature on explicit nonnative speech training programs have sought to identify the conditions under which the most successful learning can be achieved and how this interacts with individual differences among adult second language learners. However, research over the past decade has demonstrated that perceptual learning occurs following repeated presentations of a stimulus even when it is task-irrelevant (Seitz et al., 2007; Seitz et al., 2009; Seitz and Watanabe, 2003, 2005), and recent findings suggest this may benefit nonnative speech perception (Vlahou et al., 2012). In this study, we investigate whether sensitivity to nonnative speech features can be trained implicitly, that is, whether mere exposure (without instruction) to a nonnative speech feature leads to learning.

Laboratory-based speech training studies have demonstrated that “explicit learning” approaches are effective in improving sensitivity to nonnative phonetic features such as voice onset time (VOT) (McClaskey et al., 1983; Pisoni et al., 1982), the English approximants /r/-/l/ (Strange and Dittmann, 1984), fricative voicing (Jamieson and Morosan, 1986), vowels (Nishi and Kewley-Port, 2007), and lexical tones (Wayland and Guion, 2004). Numerous task-related factors are thought to contribute to positive learning outcomes in speech training programs, two of the most commonly investigated being high stimulus variability and trial-by-trial feedback. High stimulus variability exposes learners to a wide variety of exemplars of the feature or contrast to be learned, resulting in more robust representations of the learned features, thus improving generalization to novel stimuli. High variability training approaches have been successful in teaching listeners to discriminate a variety of nonnative speech contrasts (Barcroft and Sommers, 2005; Bradlow et al., 1997; Bradlow et al., 1999; Kingston, 2003; Lively et al., 1993; Lively et al., 1994; Logan et al., 1991; Pruitt, 1995), including training English listeners to differentiate Mandarin Chinese lexical tones (Wang et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2003). Trial-by-trial feedback provides information to a subject about their performance after each trial, and is thought to promote learning by directing attention to the critical stimulus features that need to be differentiated. Presenting feedback immediately following a subject's response is sometimes referred to as supervised learning and is reported to lead to superior learning (Goudbeek et al., 2008).

In recent years, an increasing number of speech training studies have investigated individual differences in learning. Individual differences among learners, including cognitive factors such as phonological awareness and phonological working memory predict measures of second language acquisition such as vocabulary growth (Papagno et al., 1991). Further, such cognitive factors may interact with training parameters to determine the success of learning. In a study of lexical tone learning, native English subjects with good pre-training pitch discrimination abilities benefitted from high variability training, whereas those with poor pre-training discrimination abilities were hindered by high variability (Perrachione et al., 2011; Wong and Perrachione, 2007). The active control model (Magnuson and Nusbaum, 2007; Nusbaum and Magnuson, 1997) is a cognitive theory of speech perception that accounts for the effects of stimulus variability on perceptual performance. According to the model, closed-loop processing routines called active control structures monitor incoming stimuli in a context sensitive way. Crucially, this active control draws from a finite pool of cognitive resources and thus when variability in the signal increases, more cognitive resources are required, and perceptual performance will decline when these resources are depleted. Most commonly, the active control model has been applied to the well-established processing costs incurred by talker variability (Lively et al., 1993; Logan et al., 1991; Mullennix et al., 1989). However, similar processing costs might be expected when irrelevant stimulus features vary during learning, as this would make the learners' task of focusing on the critical stimulus feature more difficult. Note that all of the phonetic training studies reviewed above employed an explicit learning paradigm in which great importance was placed on directing subjects' attention to the critical stimulus feature to be learned. Subjects were informed about the nonnative phonetic feature to be learned, and the number of categories required so as to focus their attention on the critical phonetic feature of interest.

An extensive literature on “implicit learning” suggests that learning can occur after exposure to a stimulus feature, in an unsupervised manner, through powerful mechanisms that track statistical regularities in the environment. Seitz and Watanabe (2003, 2009) have formalized this approach in the task-irrelevant perceptual learning framework (TIPL), a model in which perceptual learning is gated by diffuse reinforcement and learning signals that are elicited upon processing of important stimuli. According to the TIPL, stimulus features may be learned whether attended to or not, even if presented below the limens of detectability. A key prediction of the TIPL is that during the course of performing a task, unattended stimulus features will be learned, even if they are irrelevant, as long as they are systematically paired with successfully processed task targets within a critical time window. Initially, the TIPL was applied to learning in a variety of tasks in the visual modality (Frankó et al., 2009; Seitz et al., 2007; Seitz et al., 2009; Seitz and Watanabe, 2005). Although the majority of these studies have focused on nonlinguistic skills, such an approach may be applied to the acquisition of languages. Studies on language acquisition have shown that statistical mechanisms play an important role in the development of phonetic categories, which are shaped and modified by the distributional characteristics of phonetic exemplars in the speech input (Guenther and Gjaja, 1996; Maye et al., 2008; Pierrehumbert, 2003). The TIPL suggests the factors that are often thought to be required for phonetic learning might be unnecessary, such as, directing the learner's attention to the critical feature, awareness of the number of categories to be learned, and the presentation of trial-by-trial feedback. Seitz et al. (2010) found support for the TIPL in the auditory modality by showing that subjects could implicitly learn to detect single formant transitions paired at subthreshold levels with attended targets in an unrelated auditory identification task. Recently, Vlahou et al. (2012) demonstrated that implicit training of the Hindi dental-retroflex contrast in Greek listeners led to superior learning than explicit training of the same amount, consistent with the predictions of the TIPL. These findings suggest that difficult nonnative phonetic features can be learned implicitly, without directing the subjects' attention to the feature being learned.

In the present study, we tested the robustness of the hypothesis put forth by the TIPL concerning whether implicit learning can be applied to the acquisition of nonnative phonetic features. Our aim was to assess whether implicit exposure to a varying nonnative phonetic feature during explicit training of another nonnative feature will result in learning of both nonnative phonetic features. To test this, we trained separate groups of English listeners to discriminate one of two nonnative features, namely, voice onset time or lexical tone. VOT refers to the timing relationship between the start of vocal fold vibration relative to the release of a stop consonant (Lisker and Abramson, 1964). VOT differentiates stop-voicing categories across a wide variety of languages. For example, English distinguishes aspirated from unaspirated VOT, but the distinction between prevoiced and unaspirated stops is not meaningful. For prevoiced stops, the vocal folds begin vibrating during the stop closure and continue through the release of the stop. Unaspirated stops are voiceless, and vocal fold vibration begins shortly after the release of the stop. English listeners typically identify prevoiced [b, d, g] and unaspirated stops [p, t, k] as phonologically voiced /b, d, g/, respectively (Antoniou et al., 2012). Lexical tones are pitch contours that differentiate word meanings in tone languages. For example, in Mandarin, /ma/ means mother, hemp, or scold when spoken with level, rising or falling pitch, respectively. In English, pitch is not used to signal lexical distinctions. Thus, we trained subjects to distinguish words spoken with level, rising, or falling tones (corresponding to Mandarin tones 1, 2, and 4). Psychoacoustic studies have demonstrated that learning of VOT requires listeners to use temporal cues to successfully categorize stimuli along the VOT dimension (Holt et al., 2004; Llanos et al., 2013), whereas tone learning requires listeners to process both spectral and temporal acoustic cues (Kong and Zeng, 2006; Tyler et al., 1982). Therefore, the present study will contribute to our understanding of the relationships between selected acoustic phonetic details and how they drive learning.

Half of the subjects were trained to distinguish VOT and the other half were trained on lexical tone. We employed methods that have been shown to be effective in past explicit speech training studies, namely, talker variability, and trial-by-trial feedback (for a review, see Bradlow, 2008). Subjects received explicit instructions regarding the feature to be learned. Critically, half of the subjects were trained using stimuli that varied not only on the training feature, but in the irrelevant feature as well. For example for VOT training, one group was explicitly trained to distinguish prevoiced and unaspirated VOT, but lexical tones also statistically varied during training, although it was not brought to the subjects' attention. According to the TIPL, this systematic pairing with successfully processed stimuli should be sufficient for implicit learning of the unattended stimulus dimension. The other VOT training group received standard training in which VOT varied and lexical tone was held constant (always spoken with level pitch). By manipulating whether the irrelevant feature varied, we can test if subjects' sensitivity to it increases as a result of exposure, as would be predicted by the TIPL. If this turns out to be the case, then this would have important pedagogical implications for the rapid acquisition of nonnative speech contrasts. If not, then it would suggest that TIPL is restricted to low level, rather than abstract phonological categories that differentiate word meanings (i.e., lexically meaningful differences in VOT or tone), and that varying irrelevant stimulus features may tax cognitive resources and impede learning, consistent with the active control model.

II. METHOD

A. Participants

Eighty young adult native speakers of American English participated in this study. All were undergraduate students at Northwestern University. None of the subjects reported any history of audiologic or neurological deficits. All passed a pure tone screening at 25 dB at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. None possessed prior experience with a tone language.

Subjects were assigned to one of four groups (n = 20 per group). Two groups were trained to identify lexical tones, and the other two groups were trained to identify stop-voicing. This training feature factor was crossed with a variability factor. Within each training feature, one group received training in which only the relevant feature varied, and the other feature was held constant. For the other group, both features varied. This resulted in four groups: tone training with fixed VOT (Tone-fv), tone training with varying VOT (Tone-vv), VOT training with fixed tone (VOT-ft), VOT training with varying tone (VOT-vt). A series of univariate analysis of variance (ANOVAs) confirmed that the four groups were matched for age, p = 0.490, tone identification at pre-test, p = 0.952, VOT identification at pre-test, p = 0.864, and auditory working memory, p = 0.860, and sound blending, p = 0.987, as measured by the subtests of the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities (Woodcock et al., 2001) (see Table I).

TABLE I.

The four training groups were matched for age, pre-test identification accuracy of tone and VOT, as well as cognitive measures of working memory. SB = sound blending subtest of Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities. AWM = auditory working memory subtest of Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities.

| Age | Tone ID (pre) | VOT ID (pre) | SB | AWM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | M | SEM | M | SEM | M | SEM | ||

| Tone-fv | 20 | 20.8 | 0.7 | 82.4 | 0.03 | 64.7 | 0.03 | 119.4 | 119.5 |

| Tone-vv | 20 | 19.9 | 0.3 | 82.2 | 0.04 | 64.6 | 0.03 | 119.5 | 118.3 |

| VOT-ft | 20 | 20.9 | 0.5 | 80.0 | 0.04 | 67.9 | 0.03 | 120.5 | 116.3 |

| VOT-vt | 20 | 20.3 | 0.4 | 80.8 | 0.03 | 65.5 | 0.03 | 120.3 | 118.5 |

B. Stimulus materials

In total, 12 native speakers of Hindi (Mage = 24.8, six males, six females) produced all stimuli for this study. Four native speakers of Hindi (two males and two females) produced the Hindi stops /b, p, d, t/ in /Ca/ and /Cu/ contexts, which were the stimuli for the tone identification and VOT identification tests. A separate group of four speakers (two males, two females) produced the training stimuli, and another separate group of four speakers (two males, two females) produced the generalization test stimuli. The nonsense words bame /bɛɪm/, besh /bɛʃ/, pame /pɛɪm/, pesh /pɛʃ/, dahb /da:b/, and tahb /ta:b/ were used for training and generalization. Recordings were conducted in a sound-attenuated recording booth at Northwestern University using a Shure SM10A headset cardioid microphone, Roland UA25-EX audio interface, and a laptop computer. Recordings were digitized at 44.1 kHz with a 16-bit sampling depth.

The purpose of the stimulus development process was to produce stimuli that varied in two nonnative features from the perspective of English listeners: VOT and tone. Hindi speakers were selected for the recording process because they are able to produce the required prevoiced vs short-lag unaspirated VOT distinction that is nonnative for English speakers. Prevoiced tokens were created by excising the voicing lead portion from the original recording (e.g., from [ba]) and concatenating the voicing lead and the short-lag token (e.g., [pa]). This meant that the only difference between the final prevoiced and unaspirated tokens was the addition of prevoicing. The tokens were otherwise physically identical (see Fig. 1). Three tones (level, rising, and falling) were superimposed onto each stimulus token (see Fig. 2), using the pitch-synchronous overlap-add resynthesis function in Praat (Boersma and Weenink, 2001). Values used for tone synthesis are shown in Table II. The full stimulus set consisted of 288 tokens (6 talkers × 2 genders × 2 voicing categories × 3 tones × 4 targets).

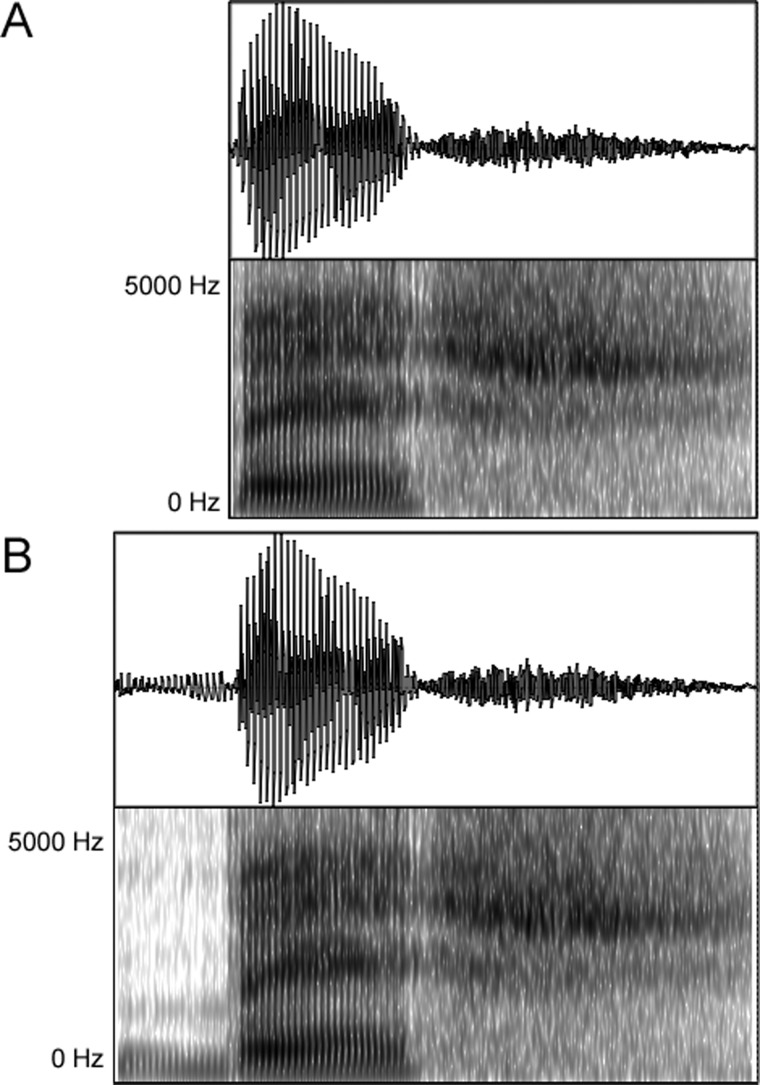

FIG. 1.

Short-lag unaspirated vs prevoiced VOT distinction depicted in oscillograms (top) and spectrograms (bottom) of the nonwords /pɛʃ/ (A) and /bɛʃ/ (B). Stimuli differing in VOT were created by concatenating the short-lag unaspirated stimulus (A) with prevoicing excised from a separate recording to create a new prevoiced stimulus (B) that was otherwise physically identical to A.

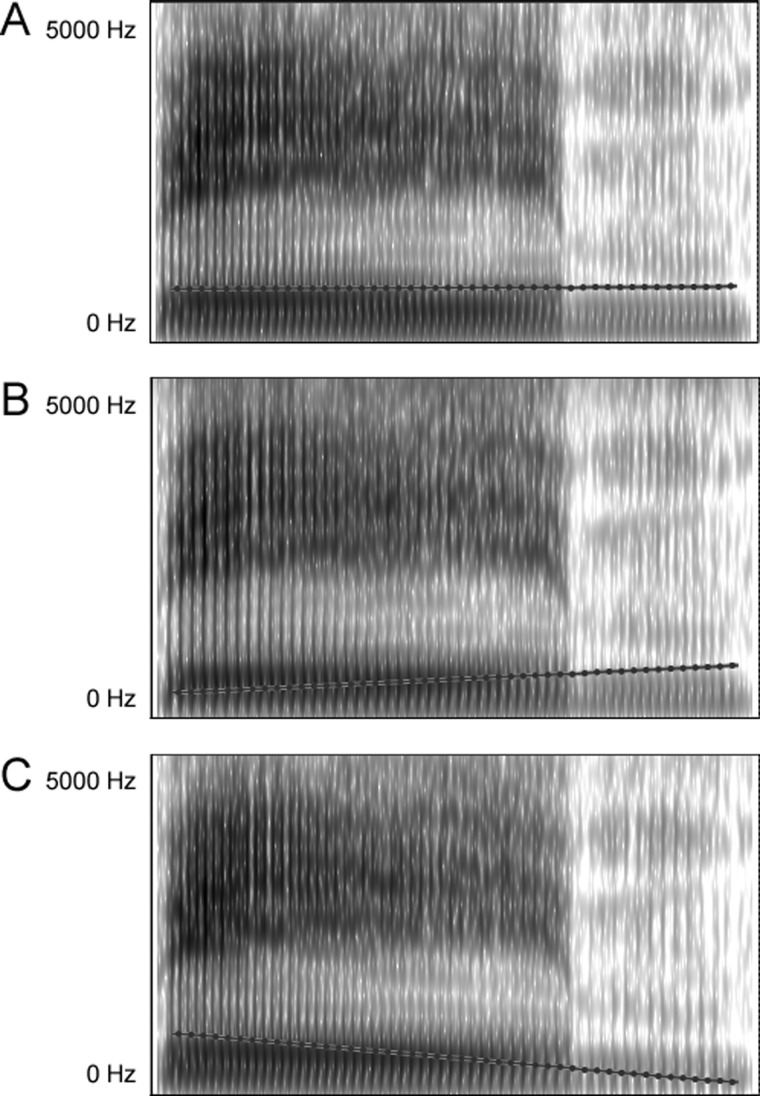

FIG. 2.

Spectrograms of the nonword /pɛɪm/ resynthesized with level (A), rising (B), and falling (C) tones. Stimuli differing in tone were created via pitch-synchronous overlap-add resynthesis, resulting in three tokens with differing pitch contours but that were otherwise acoustically similar.

TABLE II.

F0 values (Hz) used for pitch-synchronous overlap-add resynthesis for the six male (M) and six female (F) talkers.

| Talker | Tone 1 | Tone 2 | Tone 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| start | end | start | end | start | end | |

| M1 | 169 | 165 | 125 | 172 | 184 | 102 |

| M2 | 142 | 142 | 107 | 138 | 156 | 88 |

| M3 | 162 | 164 | 125 | 173 | 179 | 102 |

| M4 | 142 | 145 | 106 | 142 | 153 | 88 |

| M5 | 164 | 166 | 123 | 163 | 189 | 104 |

| M6 | 145 | 144 | 102 | 143 | 157 | 85 |

| F1 | 213 | 215 | 157 | 210 | 231 | 130 |

| F2 | 264 | 261 | 193 | 264 | 288 | 160 |

| F3 | 238 | 234 | 175 | 236 | 260 | 144 |

| F4 | 209 | 207 | 149 | 209 | 223 | 128 |

| F5 | 244 | 243 | 184 | 242 | 267 | 149 |

| F6 | 199 | 212 | 154 | 211 | 231 | 126 |

We had native Hindi and Mandarin judges identify each token to confirm the validity of the stimulus set. Three fluent Hindi speakers identified all 288 stimuli on the basis of stop-voicing with 93%–95% accuracy. Two problematic sets of tokens were identified and replaced with new tokens (note that each set is comprised of six tokens because from each original recording, tokens were created for two voicing categories × three tones). Two fluent Mandarin speakers confirmed that the revised set of 288 stimuli were acceptable versions of level, rising, and falling tones (97.1% and 97.9% identification accuracy).

C. Procedure

Subjects completed a seven-day training protocol. On day 1, subjects completed experimental paperwork, including a demographics questionnaire, cognitive tests, and tone identification and VOT identification pre-tests. The order of the pre-tests was counterbalanced. Subjects were then assigned to a training group and completed their first training session. On days 2–6, subjects returned and repeated the training session. On day 7, subjects completed their final training session, followed by the generalization test, and the tone identification and VOT identification post-tests. The order of the two post-tests was counterbalanced. All experimental tasks were presented via a computer running E-Prime software, and audio stimuli were presented using Sennheiser HD280 Pro headphones at a calibrated output level of about 72 dB sound pressure level (SPL).

1. Tone identification test

Tone identification was assessed at two time points, namely, before and after training (pre-test and post-test, respectively). The tone identification test consisted of 96 trials (2 consonants × 2 voicing × 2 vowels × 3 tones × 4 talkers). On each trial, an auditory stimulus was presented and two arrows appeared onscreen as response options representing its pitch contour (i.e., two of →, ↗, ↘ representing level, rising, and falling pitch contours, respectively). The placement of the response options was counterbalanced. Subjects selected one of the two pitch contours by pressing a button on a low-latency response box. Stimuli were presented at the rate of one every 3 s. No corrective feedback was provided.

2. VOT identification test

The VOT identification test was identical to the tone identification test, with the exception that subjects were required to indicate whether the stop consonant on each trial contained prevoicing of short-lag unaspirated VOT. Response options were presented onscreen using English orthography. Short-lag unaspirated VOT was represented by the stops b and d (e.g., ba, bu, da, du). Prevoicing was represented orthographically by preceding the stop with a nasal (e.g., prevoiced ba = mba, prevoiced du = ndu). The experimenter ensured that each subject understood the response options before beginning the test. The placement of the response options was counterbalanced.

3. Training

Subjects completed seven training sessions, each held on a separate day. Subjects were permitted no more than two consecutive days without a session. Half of the subjects were trained to associate pictures with spoken pseudowords varying in tone, the other half in VOT. Each training session involved 96 exposure trials and 48 test trials. In each block of four exposure trials, the subject was passively exposed to two repetitions of two words in random order. Immediately following the four passive exposure trials, subjects were then quizzed on those two words. Each word was presented and subjects were required to select the correct picture out of the two options. Corrective trial-by-trial feedback was provided. Stimuli were presented at the rate of one every 3 s.

At the end of the session, subjects completed a word learning test. For the test trials, subjects were given a sheet containing 24 pictures. Each word was presented and subjects were required to respond by pressing the key corresponding to the picture on the sheet. No feedback was provided. The order of the test words was randomized. There were 48 test trials in total (4 talkers × 12 words).

4. Generalization test

After completing all seven training sessions, subjects completed the generalization task on the final day. The structure of the generalization task was similar to the word learning test presented at the end of each training session. Four new talkers produced each pseudoword, and subjects selected the correct item from the list of 24 pictures. No feedback was provided. There were 48 generalization trials in total (4 talkers × 12 words), which were presented in random order. Stimuli were presented at the rate of one every 3 s.

III. RESULTS

A. Training and generalization

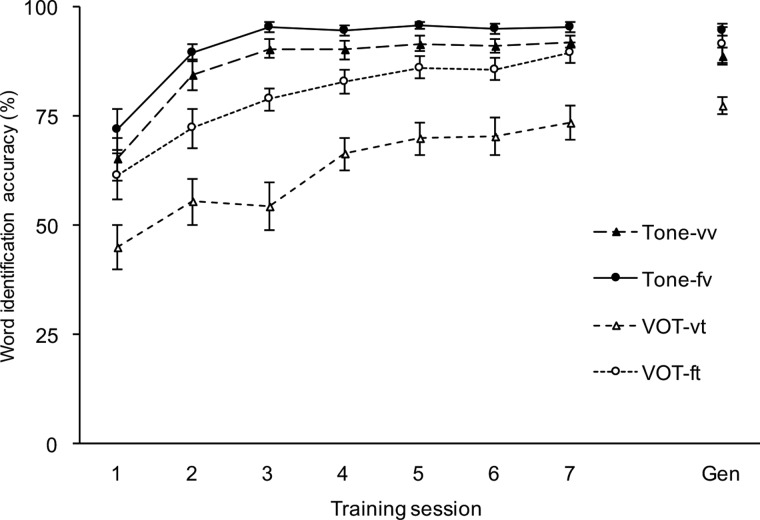

Figure 3 shows each group's learning achievement over the seven-day training protocol, including their generalization, which measures ultimate attainment. We compared generalization via a 2 × 2 ANOVA with the between-subjects factors of Training feature (tone vs VOT) and Variation of irrelevant feature (varying vs fixed). A main effect of training feature revealed that, overall, subjects who learned to identify tones (the filled shapes in Fig. 3) achieved superior generalization, F(1, 76) = 9.8, p = 0.002, = 0.115. A main effect of variation confirmed that subjects who were trained with the relevant feature varying and the irrelevant feature fixed (the circles in Fig. 3) achieved better generalization than subjects who were trained with both features varying (the triangles in Fig. 3), F(1, 76) = 13.4, p < 0.001, = 0.150. There was also a marginally significant Training × Variation interaction, F(1, 76) = 3.3, p = 0.072, = 0.042.

FIG. 3.

Word identification accuracy (%) across seven training sessions and in the generalization test (Gen). Tone training (filled shapes) led to superior generalization than VOT training (empty shapes). Keeping the irrelevant feature fixed (circles) led to superior generalization than training in which the irrelevant feature varied (triangles). Error bars depict standard error of the mean.

We next examined the effect of variation on each training feature using planned comparisons. A Bonferroni-adjusted α level of 0.025 was employed to control for type I error inflation (0.05/2 = 0.025). For tone training, subjects achieved better generalization outcomes when VOT was fixed during training relative to when VOT varied (94.7% vs 88.6%, respectively), t(38) = 2.7, p = 0.012. Similarly, for VOT training, superior generalization was observed when tone was fixed during training compared to when both features varied (91.4% vs 77.4%, respectively), t(26.4) = 3.13, p = 0.004.

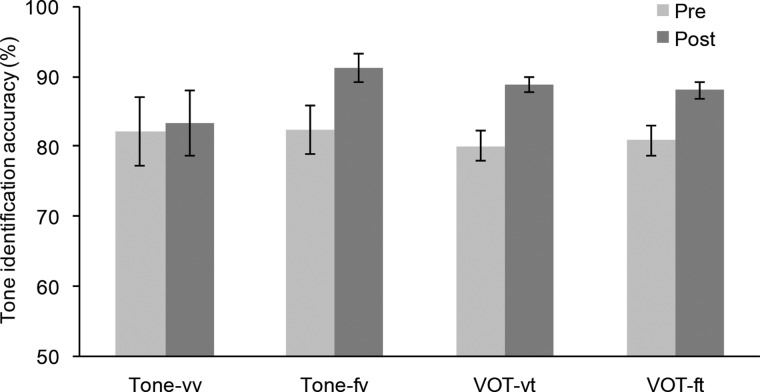

B. Tone identification at pre- vs post-test

The purpose of the tone and VOT identification tests was largely to match subjects across the various experimental conditions, because pre-training sensitivity to a stimulus feature predicts learning (Perrachione et al., 2011) and thus must be controlled (see Table I). However, we also examined identification of both stimulus features at post-test to examine the effects of training and exposure on identification. Tone identification accuracy at pre- and post-test is shown in Fig. 4. We examined the effect of training on tone identification via a 2 × 2 × (2) ANOVA with the between-subjects factors of training feature (tone vs VOT) and variation of irrelevant feature (varying vs fixed), and the within-subjects factor of test (pre- vs post-test). A significant main effect of test confirmed that subjects identified tones more accurately following the completion of training compared to at pre-test, F(1, 76) = 53.7, p < 0.001, = 0.414. There was also a significant Test × Variation interaction, F(1, 76) = 6.6, p = 0.012, = 0.080. We conducted a post hoc t-test on the difference in tone identification accuracy between pre- and post-test which revealed that subjects who received training with the irrelevant feature fixed showed greater improvements than those for which both features varied, t(78) = 2.5, p = 0.014. There were no other significant effects or interactions.

FIG. 4.

Tone identification accuracy (%) at pre- and post-test. Error bars depict standard error of the mean.

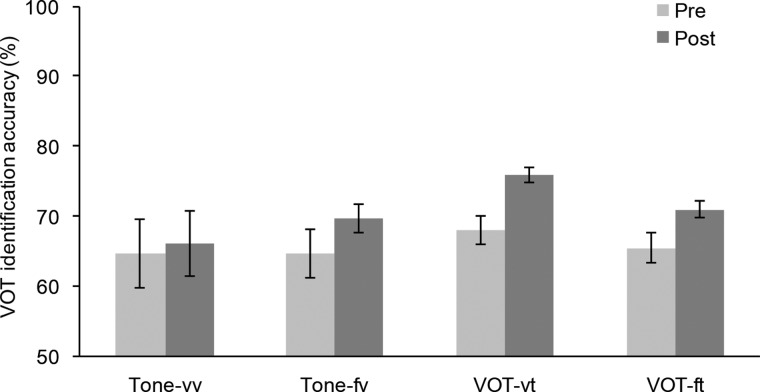

C. VOT identification at pre- vs post-test

VOT identification accuracy at pre- and post-test is shown in Fig. 5. We examined VOT identification via a 2 × 2 × (2) ANOVA. A main effect of test revealed that subjects scored higher in VOT identification at post-test than at pre-test, F(1, 76) = 12.2, p = 0.001, = 0.138. There were no other significant effects or interactions.

FIG. 5.

VOT identification improved from pre- to post-test for all groups. Error bars depict standard error of the mean.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study investigated whether nonnative phonetic features may be learned implicitly by exposing learners to a nonnative feature that statistically varies. Phonetic training of nonnative lexical tones and VOT distinctions yielded the best learning outcomes when only the relevant phonetic feature varied and the irrelevant feature was held constant. Varying both features during training hindered learning and generalization.

Focusing the learner's attention on the training feature appears to be an important element of nonnative speech training. This is consistent with the active control model (Magnuson and Nusbaum, 2007; Nusbaum and Magnuson, 1997), and a large literature of explicit laboratory-based speech training studies (Barcroft and Sommers, 2005; Bradlow et al., 1999; Bradlow et al., 1997; Kingston, 2003; Lively et al., 1993; Lively et al., 1994; Logan et al., 1991; Pruitt, 1995). Such studies are designed to draw the learners' attention to the critical phonetic feature to be learned. Our data suggest that “explicit” approaches to nonnative speech training are an effective method of training. Our results cannot be attributed to pre-training differences in sensitivities to tone or VOT, or differences in working memory availability since each of these factors were controlled. Thus, it is extremely likely that the observed differences in learning were due to differences in training paradigm, namely, whether the irrelevant stimulus feature varied.

These findings indicate that, in adults, exposure to a stimulus feature may not be sufficient for learning, especially when there is resistance to learning, such as that encountered by an attuned phonological system when attempting to accommodate nonnative phonetic features. Additionally, we demonstrate that some nonnative phonetic features are more difficult to learn than others. Here, learners who were trained to distinguish lexical tones reached higher levels of generalization than those trained to distinguish VOT. It is worth noting that this was the case even though subjects were required to learn three tone categories vs only two VOT categories. This difference in learnability between the two stimulus dimensions is consistent with phonetic learning studies from our laboratory (e.g., Antoniou et al., 2015) and theories of nonnative speech perception (Best and Tyler, 2007).

According to the TIPL, irrelevant stimulus features will be learned if they are systematically paired with successfully processed targets. The present findings suggest that the TIPL may require extension. Implicit exposure to meaningful statistical variation is not sufficient for learning nonnative phonetic features that differentiate word meanings. One possibility is that the TIPL may be restricted to low level stimulus features such as detecting single formant transitions (Seitz et al., 2010), contrary to the suggestion of Vlahou et al. (2012) who claim that implicit training of nonnative phonetic features leads to superior learning outcomes than explicit training approaches. A second possibility may be that the TIPL accurately describes learning of stimulus features presented at subthreshold levels, but when presenting stimuli above threshold, interference may occur and thus failure to learn may reflect inefficiencies of selective attention. Consistent with this view, our data suggest that focusing subjects' attention on the relevant phonetic features and minimizing variation in other irrelevant features yields the best learning outcomes. Further, varying irrelevant stimulus features may actually hinder learning of the relevant training feature, consistent with the active control model.

Learning theories based on unsupervised mechanisms, such as statistical learning, have made important contributions to our understanding of how learners track statistical regularities of the environment (Guenther and Gjaja, 1996; Maye et al., 2008; Pierrehumbert, 2003). However, purely unsupervised accounts do not explain the learning of difficult nonnative phonetic contrasts by adults, because it is well established that prolonged exposure to nonnative phonetic contrasts does not lead to the development of native-like phonetic categories (Flege, 2002; Munro and Bohn, 2007; Strange, 1995). Based on our data, we recommend an explicit approach to nonnative speech category learning. Implicit approaches may not direct the learners' attention to learn the abstract relationship between stimulus features and meaning.

Moving forward, it is necessary to develop a clearer understanding of how individual differences interact with training paradigm design in order to tailor training to maximize learning outcomes. In the present study, groups were matched in their pre-training aptitudes to tone and VOT, age, and working memory, in order to isolate the contribution of varying the irrelevant stimulus feature. Individual differences in pre-training aptitude (Perrachione et al., 2011) and working memory availability may affect learning of nonnative phonetic categories. In future, it would be beneficial to examine how these individual differences interact with such an implicit training approach.

In conclusion, phonetic training of nonnative phonetic features resulted in the best learning outcomes when only the relevant phonetic feature varied and the irrelevant feature was held constant. Contrary to the predictions of the TIPL, permitting the irrelevant features to vary hindered learning of the target feature. Our findings have implications for theories of nonnative phonetic learning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant Nos. R01DC008333 and R01DC013315, National Science Foundation Grant No. BCS-1125144, Research Grants Council of Hong Kong Grant Nos. 477513 and 14117514 to P.C.M.W., and Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award DE150101053 to M.A.

References

- 1. Antoniou, M. , Liang, E. , Ettlinger, M. , and Wong, P. C. M. (2015). “ The bilingual advantage in phonetic learning,” Biling. Lang. Cogn. 18, 683–695. 10.1017/S1366728914000777 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antoniou, M. , Tyler, M. D. , and Best, C. T. (2012). “ Two ways to listen: Do L2-dominant bilinguals perceive stop voicing according to language mode?,” J. Phon. 40, 582–594. 10.1016/j.wocn.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barcroft, J. , and Sommers, M. S. (2005). “ Effects of acoustic variability on second language vocabulary learning,” Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 27, 387–414. 10.1017/S0272263105050175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Best, C. T. , and Tyler, M. D. (2007). “ Nonnative and second-language speech perception: Commonalities and complementarities,” in Language Experience Second Language Learning in Honor of James Emil Flege, edited by Bohn O.-S. and Munro M. J. ( John Benjamins, Amsterdam: ), pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boersma, P. , and Weenink, D. (2001). “ Praat, a system for doing phonetics by computer,” Glot Int. 5, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bradlow, A. R. (2008). “ Training non-native language sound patterns: Lessons from training Japanese adults on the English / ɹ /–/l/ contrast,” in Phonology and Second Language Acquisition Studies in Bilingualism, edited by Hansen Edwards J. G. and Zampini M. L. ( John Benjamins, Amsterdam: ). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradlow, A. R. , Akahane-Yamada, R. , Pisoni, D. B. , and Tohkura, Y. (1999). “ Training Japanese listeners to identify English /r/and /l/: Long-term retention of learning in perception and production,” Percept. Psychophys. 61, 977–985. 10.3758/BF03206911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bradlow, A. R. , Pisoni, D. B. , Akahane-Yamada, R. , and Tohkura, Y. (1997). “ Training Japanese listeners to identify English /r/ and /l/: IV. Some effects of perceptual learning on speech production,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 101, 2299–2310. 10.1121/1.418276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flege, J. E. (2002). “ Interactions between the native and second-language phonetic systems,” in An Integrated View of Language Development: Papers in Honor of Henning Wode, edited by Burmeister P., Piske T., and Rohde A. ( Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Trier, Germany: ), pp. 217–243. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frankó, E. , Seitz, A. R. , and Vogels, R. (2008). “ Dissociable neural effects of long-term stimulus–reward pairing in macaque visual cortex,” J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22, 1425–1439. 10.1162/jocn.2009.21288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goudbeek, M. , Cutler, A. , and Smits, R. (2008). “ Supervised and unsupervised learning of multidimensionally varying non-native speech categories,” Speech Commun. 50, 109–125. 10.1016/j.specom.2007.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guenther, F. H. , and Gjaja, M. N. (1996). “ The perceptual magnet effect as an emergent property of neural map formation,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 100, 1111–1121. 10.1121/1.416296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holt, L. L. , Lotto, A. J. , and Diehl, R. L. (2004). “ Auditory discontinuities interact with categorization: Implications for speech perception,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am 116(3), 1763–1773. 10.1121/1.1778838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jamieson, D. G. , and Morosan, D. E. (1986). “ Training non-native speech contrasts in adults: Acquisition of the English /ð/-/θ/ contrast by francophones,” Percept. Psychophys. 40, 205–215. 10.3758/BF03211500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kingston, J. (2003). “ Learning foreign vowels,” Lang. Speech 46, 295–348. 10.1177/00238309030460020201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kong, Y.-Y. , and Zeng, F.-G. (2006). “ Temporal and spectral cues in Mandarin tone recognition,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 120, 2830–2840. 10.1121/1.2346009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuhl, P. K. , Williams, K. A. , Lacerda, F. , Stevens, K. N. , and Lindblom, B. (1992). “ Linguistic experience alters phonetic perception in infants by 6 months of age,” Science 255, 606–608. 10.1126/science.1736364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lisker, L. , and Abramson, A. S. (1964). “ A cross-linguistic study of voicing in initial stops: Acoustical measurements,” Word 20, 384–422. 10.1080/00437956.1964.11659830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lively, S. E. , Logan, J. S. , and Pisoni, D. B. (1993). “ Training Japanese listeners to identify English /r/ and /l/. II: The role of phonetic environment and talker variability in learning new perceptual categories,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 94, 1242–1255. 10.1121/1.408177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lively, S. E. , Pisoni, D. B. , Yamada, R. A. , Tohkura, Y. , and Yamada, T. (1994). “ Training Japanese listeners to identify English /r/ and /l/. III. Long-term retention of new phonetic categories,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 96, 2076–2087. 10.1121/1.410149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Llanos, F. , Dmitrieva, O. , Shultz, A. , and Francis, A. L. (2013). “ Auditory enhancement and second language experience in Spanish and English weighting of secondary voicing cues,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 134, 2213–2224. 10.1121/1.4817845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Logan, J. S. , Lively, S. E. , and Pisoni, D. B. (1991). “ Training Japanese listeners to identify English /r/ and /l/: A first report,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 89, 874–886. 10.1121/1.1894649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Magnuson, J. S. , and Nusbaum, H. C. (2007). “ Acoustic differences, listener expectations, and the perceptual accommodation of talker variability,” J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 33, 391–409. 10.1037/0096-1523.33.2.391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maye, J. , Weiss, D. J. , and Aslin, R. N. (2008). “ Statistical phonetic learning in infants: Facilitation and feature generalization,” Dev. Sci. 11, 122–134. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00653.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McClaskey, C. L. , Pisoni, D. B. , and Carrell, T. D. (1983). “ Transfer of training of a new linguistic contrast in voicing,” Percept. Psychophys. 34, 323–330. 10.3758/BF03203044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mullennix, J. W. , Pisoni, D. B. , and Martin, C. S. (1989). “ Some effects of talker variability on spoken word recognition,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 85, 365–378. 10.1121/1.397688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Munro, M. J. , and Bohn, O.-S. (2007). “ The study of second language speech: A brief overview,” in Language Experience Second Language Learning in Honor of James Emil Flege, edited by Bohn O.-S. and Munro M. J. ( John Benjamins, Amsterdam: ), pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nishi, K. , and Kewley-Port, D. (2007). “ Training Japanese listeners to perceive American English vowels: Influence of training sets,” J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 50, 1496–1509. 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/103) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nusbaum, H. C. , and Magnuson, J. S. (1997). “ Talker normalization: Phonetic constancy as a cognitive process,” in Talker Variability and Speech Processing, edited by Johnson K. and Mullennix J. W. ( Academic, San Diego, CA: ), pp. 109–132. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papagno, C. , Valentine, T. , and Baddeley, A. (1991). “ Phonological short-term memory and foreign-language vocabulary learning,” J. Mem. Lang. 30, 331–347. 10.1016/0749-596X(91)90040-Q [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perrachione, T. K. , Lee, J. , Ha, L. Y. Y. , and Wong, P. C. M. (2011). “ Learning a novel phonological contrast depends on interactions between individual differences and training paradigm design,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 130, 461–472. 10.1121/1.3593366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pierrehumbert, J. B. (2003). “ Phonetic diversity, statistical learning, and acquisition of phonology,” Lang. Speech 46, 115–154. 10.1177/00238309030460020501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pisoni, D. B. , Aslin, R. N. , Perey, A. J. , and Hennessy, B. L. (1982). “ Some effects of laboratory training on identification and discrimination of voicing contrasts in stop consonants,” J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 8, 297–314. 10.1037/0096-1523.8.2.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pruitt, J. S. (1995). “ Perceptual training on Hindi dental and retroflex consonants by native English and Japanese speakers,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 97, 3417–3418. 10.1121/1.412451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seitz, A. R. , Kim, R. , van Wassenhove, V. , and Shams, L. (2007). “ Simultaneous and independent acquisition of multisensory and unisensory associations,” Perception 36, 1445–1453. 10.1068/p5843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seitz, A. R. , Kim, D. , and Watanabe, T. (2009). “ Rewards evoke learning of unconsciously processed visual stimuli in adult humans,” Neuron 61, 700–707. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seitz, A. R. , Protopapas, A. , Tsushima, Y. , Vlahou, E. L. , Gori, S. , Grossberg, S. , and Watanabe, T. (2010). “ Unattended exposure to components of speech sounds yields same benefits as explicit auditory training,” Cognition 115, 435–443. 10.1016/j.cognition.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seitz, A. R. , and Watanabe, T. (2003). “ Psychophysics: Is subliminal learning really passive?,” Nature 422, 36–36. 10.1038/422036a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seitz, A. R. , and Watanabe, T. (2005). “ A unified model for perceptual learning,” Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 329–334. 10.1016/j.tics.2005.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Seitz, A. R. , and Watanabe, T. (2009). “ The phenomenon of task-irrelevant perceptual learning,” Vision Res., Percept. Learn. 49, 2604–2610. 10.1016/j.visres.2009.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Strange, W. (1995). “ Cross-language studies of speech perception: A historical review,” in Speech Perception and Linguistic Experience: Issues Cross-Language, edited by Strange W. ( York Press, Baltimore, MD: ), pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Strange, W. , and Dittmann, S. (1984). “ Effects of discrimination training on the perception of /r-l/ by Japanese adults learning English,” Percept. Psychophys. 36, 131–145. 10.3758/BF03202673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tyler, R. S. , Summerfield, Q. , Wood, E. J. , and Fernandes, M. A. (1982). “ Psychoacoustic and phonetic temporal processing in normal and hearing-impaired listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 72, 740–752. 10.1121/1.388254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vlahou, E. L. , Protopapas, A. , and Seitz, A. R. (2012). “ Implicit training of nonnative speech stimuli,” J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 141, 363–381. 10.1037/a0025014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang, Y. , Jongman, A. , and Sereno, J. A. (2003). “ Acoustic and perceptual evaluation of Mandarin tone productions before and after perceptual training,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 113, 1033–1043. 10.1121/1.1531176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang, Y. , Spence, M. M. , Jongman, A. , and Sereno, J. A. (1999). “ Training American listeners to perceive Mandarin tones,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 106, 3649–3658. 10.1121/1.428217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wayland, R. P. , and Guion, S. G. (2004). “ Training English and Chinese listeners to perceive Thai tones: A preliminary report,” Lang. Learn. 54, 681–712. 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00283.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Werker, J. F. , and Tees, R. C. (1984). “ Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life,” Infant Behav. Dev. 7, 49–63. 10.1016/S0163-6383(84)80022-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wong, P. C. M. , and Perrachione, T. K. (2007). “ Learning pitch patterns in lexical identification by native English-speaking adults,” Appl. Psycholinguist. 28, 565–585. 10.1017/S0142716407070312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Woodcock, R. W. , McGrew, K. S. , and Mather, N. (2001). Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities ( Riverside, Itasca, IL: ). [Google Scholar]