Abstract

The identification of new and effective therapeutic targets for the lethal, castration-resistant stage of prostate cancer (CRPC) has been challenging because of both the paucity of adequate frozen tissues and a lack of integrated molecular analysis. Therefore, in this study, we performed a genome-wide analysis of DNA copy number alterations from 34 unique surgical CRPC specimens and 5 xenografts, with matched transcriptomic profiling of 25 specimens. An integrated analysis of these data revealed that the asparagine synthetase (ASNS) gene showed a gain in copy number and was overexpressed at the transcript level. The overexpression of ASNS was validated by analyzing other public CRPC data sets. ASNS protein expression, as detected by reverse-phase protein lysate array, was tightly correlated with gene copy number. In addition, ASNS protein expression, as determined by IHC analysis, was associated with progression to a therapy-resistant disease state in TMAs that included 77 castration-resistant and 40 untreated prostate cancer patient samples. Knockdown of ASNS by small-interfering RNAs in asparagine-deprived media led to growth inhibition in both androgen-responsive (ie, LNCaP) and castration-resistant (ie, C4-2B) prostate cancer cell lines and in cells isolated from a CRPC xenograft (ie, MDA PCa 180-30). Together, our results suggest that ASNS is up-regulated in cases of CRPC and that depletion of asparagine using ASNS inhibitors will be a novel strategy for targeting CRPC cells.

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed noncutaneous malignancy in US men and the second leading cause of cancer-specific mortality.1 The systemic form of prostate cancer is initially responsive to androgen deprivation therapy, but it invariably progresses to a castration-resistant, lethal phenotype known as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). CRPC is treated with docetaxel-based chemotherapy, which results in only a modest survival benefit.2, 3 New treatment modalities for this terminal stage of prostate cancer have largely focused on the androgen signaling axis, with development of stronger androgen receptor (AR) blockers and androgen ligand inhibitors to block intracrine ligand production.4, 5 Other pathways, such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling,6, 7 have been implicated in prostate cancer progression, but the number of identified targets has been few.8

Genomic studies to identify genes that can serve as therapeutic targets have been hindered by the limited number of castration- and chemotherapy-resistant tissues available for the comprehensive, integrated analyses that are necessary to identify robust markers for functional validation. Because CRPC tissues are not routinely sampled during a patient's illness, these latter samples have largely been derived from autopsy tissues9, 10 at the few institutions that have a rapid autopsy program in place for these patients.

To identify novel targets in CRPC, we first assembled the largest set of frozen surgical CRPC tissues and evaluated them using multiple genomic and proteomic approaches. We then narrowed the list of candidate genes to those that were biologically meaningful and potential drivers by integrating DNA copy number alterations with the transcriptomic profiles of lethal prostate cancer specimens. We cross validated our results by comparing our data with publicly available CRPC molecular profiling data sets. Asparagine synthetase (ASNS) emerged as a promising target from these analyses. ASNS overexpression was validated at the protein level in a large cohort of clinical CRPC cases via both reverse-phase protein lysate array (RPPA) and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis on TMAs. Furthermore, using appropriate cell culture and xenograft models, we established that ASNS inhibition led to decreased cell viability.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies, siRNAs, and Reagents

Rabbit monoclonal anti-human ASNS (number LS-C49697) was obtained from Lifespan Biosciences, Inc. (Seattle, WA). The TARGETplus SMARTpool human ASNS small-interfering RNA (siRNA; catalogue number L-009377-00) and the On-TARGETplus Controlpool (catalogue number D-001810-10-20) siRNA were from Dharmacon (Chicago, IL). The MTT reagent (thiazolyl blue; catalogue number M-5655) and β-actin antibody (catalogue number A2103) were from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Lipofectamine RNAiMax reagent (catalogue number 56532) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The asparaginase (Elspar) was made by Lundbeck, Inc. (Deerfield, IL). The one times radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (product 89901) was from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL).

Patient Tissue Samples

Hormone-sensitive and CRPC tissue samples were obtained from the Departments of Pathology at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX), McGill University (Montreal, QC, Canada), and the University of Montreal (Montreal, QC, Canada), with informed consent and by using Institutional Review Board–approved protocols. Initial hormone deprivation therapy included surgical orchiectomy or luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonists, with or without an anti-androgen agent. CRPC was defined as two consecutive increases in serum prostate-specific antigen by >10% during therapy, despite castrate serum levels of testosterone.

Castration-resistant samples were not graded but were histologically characterized as gland-forming adenocarcinomas or small-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas. Castration-resistant samples (n = 14) were obtained from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks of transurethral resections of men with CRPC and urinary obstruction. Frozen castration-resistant samples (n = 20) were taken from salvage cystoprostatectomies or pelvic exenteration specimens. Murine xenografts derived from five of the foregoing tumors showing adenocarcinoma histological features were also assessed. Detailed clinical annotation of CRPC samples that were molecularly profiled is provided in Supplemental Table S1 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Three TMAs, used to validate genomic data, consisted of 40 hormone-sensitive samples, 77 castration-resistant localized or metastatic samples, and 35 benign prostate tissue samples.

DNA Copy Number Assessment and Analysis

H&E-stained frozen sections of CRPC tissues were examined by two genitourinary pathologists (K.S. and P.T.), with lesional foci circled. Only sections with >75% cancer cells were accepted. DNA was extracted from macrodissected sections, with the tumor DNA copy number assessed by high-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization using Agilent's human genome comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) 244A oligo TMA kit (part G4411B; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol and as previously described.11, 12

Expression Profiling and Analysis

RNA was isolated using the mirVana total RNA protocol (part AM1560; Ambion, Austin, TX). RNA integrity was verified using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (part G2938A) with nanochips (parts 5067-15101 and G4411B; Agilent Technologies). RNA concentrations were determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Tumor mRNA expression was assessed using a human whole-genome oligo TMA kit from Agilent Technologies (product G4112F), according to the manufacturer's protocol and as previously described.13

Integrative Analysis of Copy Number and mRNA Expression

DNA copy number data were preprocessed using our standard smoothing and segmentation methods.14 DNA copy number was considered altered if the magnitude of change was log ratio >0.3, present in at least 30% of cases. We compared DNA copy number alterations in CRPC with those in the Stanford data set of hormone-sensitive prostate cancer samples (GSE6469, n = 45; see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

The mean gene expression values of five normal prostate samples were used as a reference, and the CRPC data were compared with the reference data to find up- or down-regulated genes. The gene expression data from our cohort were evaluated using stringent criteria: log ratio >0.3 for informative genes present in more than two thirds of cases. We compared our expression profiling data with data from a similar group of patients in which both CRPC and benign prostate tissues were profiled, including the University of Michigan (GDS1439), University of Tokyo (GSE6811), and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (GSE21032) data sets (available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

For each gene expression data set, genes that appeared in >40% samples as up- or down-regulated were considered as up- or down-regulated. The same process was applied to DNA copy number data sets to identify amplified or deleted genes. For each data set, two gene lists were generated. The up-regulated/amplified or down-regulated/deleted genes in both lists were considered candidates for further study.

RPPA Data

Serial diluted cell lysates were placed on nitrocellulose-coated slides, as previously described,15 using an Aushon 2470 Arrayer (Aushon BioSystems, Billerica, MA). Each slide was probed with a validated primary antibody plus a biotin-conjugated secondary antibody. Each dilution curve was fitted with a logistic model (Supercurve Fitting, developed by the Department of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center; http://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/Software/supercurve, last accessed January 10, 2012). The protein concentrations of each set of slides were then normalized by the median polish method, which normalizes the values across samples using the linear expression values of the median expression levels of all antibodies.

IHC Analysis

Standard diaminobenzidine IHC analyses of TMAs representing benign prostate, primary hormone-sensitive and CRPC, and metastatic CRPC samples were performed with a Dako AutoStainer Plus (Dako, Carpentaria, CA) using rabbit anti-human monoclonal ASNS antibody (catalogue number LS-C49697; Life Span Bio, Seattle, WA) at a 1:50 dilution, as previously described.16 Immunoreactivity was manually graded as percentage positive staining of tumor cells.

Cell Culture

C4-2B cells, deposited at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, were developed after serial passage of androgen-responsive lymph node prostate cancer (LNCaP) cells in castrated hosts when the cells were no longer responsive to androgen manipulation in animals.17 LNCaP cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Both cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C with an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Xenograft Studies

The tissue specimens used to develop MDA PCa 79, MDA PCa 117-9, MDA PCa 124, MDA PCa 130, MDA PCa 149-1, and MDA PCa 180-30 xenografts were derived from tumor samples of surgical specimens (cystoprostatectomy, radical prostatectomy, or pelvic exenteration) of a progressive primary CRPC. Small pieces of tumor (derived from the prostate or a local tumor extension) were implanted into s.c. pockets of 6- to 8-week-old male CB17 mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Tumors developed within 6 months of implantation and were maintained in the mice, because the cells did not sustain in vitro growth. The passage and tumor-processing methods used were as reported elsewhere.18 Written informed consent had been obtained from patients before sample acquisition, and samples were processed according to a protocol approved by the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board, including approval from the animal care and use committee.

Short-term cultures of MDA PCa 180-30 xenografts were prepared from s.c. tumors in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Xenograft MDA PCa 180-30 was derived from a man with metastatic Gleason 9 (4 + 5) prostate cancer. The patient received maximum androgen blockade but later relapsed with castration-resistant disease. He then received docetaxel and carboplatin chemotherapy. Local pelvic symptoms persisted after chemotherapy, and the patient underwent surgical consolidation with cystoprostatectomy, from which the CRPC specimen was derived and grown as murine xenografts. A representative photomicrograph of MDA PCa 180-30 is shown in Supplemental Figure S1 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In brief, tumors were digested with Accumax (Innovative Cell Technologies, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The cell suspensions were filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer and gently loaded onto a Histopaque-1077 gradient and centrifuged at 400 × g for 30 minutes. The interphase-containing mononuclear cells were carefully removed, and the cells were washed with PBS and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in petri dishes or 6-well plates coated with FNC Coating Mix (Athena Environmental Sciences, Inc, Baltimore, MD).

siRNA Transfection and Western Blot Analysis

siRNA transfection was performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMax Reagent (catalogue number 56532; Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's protocol. The final concentration of the siRNA was 50 nmol/L. Western blot analysis was performed as previously described.19 Briefly, cell extracts containing 20 μg of protein were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, transferred to Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ), or polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (catalogue number IPVH20200) from Millipore Corporation (Billerca, MA), blocked in 5% nonfat milk in one times Tris-buffered saline plus Tween (pH 8.0), and probed with primary antibodies at concentrations of 1:1000 for ASNS and 1: 2500 for β-actin. The secondary antibodies were used at concentrations of 1:10,000. The proteins were visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (product 34708) or the SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (product 34096) from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Cell Proliferation Assays

Cell proliferation was determined by MTT absorbance. The cells transfected with the control siRNA or ASNS siRNA (si-ASNS) were trypsinized from the dishes at 48 hours after transfection, and 4000 cells in a volume of 200 μL of complete medium were seeded into each well of a 96-well plate (n = 6). The cells were allowed to attach for 24 hours in the complete medium. One plate of cells was used for MTT assay after 24 hours of incubation and served as the 0-hour time point. The remaining cells were left untreated or treated with 500 U/mL of asparaginase and continually incubated under normal cell culture conditions. MTT assays were performed at 24-hour intervals. Additional asparaginase was added to each treated well, and the concentration of the drug was kept at 500 U/mL. After incubation, 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg per mL) was added to each well and incubated for 4 hours under normal cell culture conditions. The wells were emptied by vacuum aspiration, and 200 μL of dimethylsulfoxide was added. Absorbance was measured at 590 nm with a microplate reader (MRX; Danatech Laboratory, Houston, TX).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test. Differences in means were evaluated using a two-tailed t-test, assuming unequal variances. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. P values are calculated using one-way analysis of variance, which determines the null hypothesis of two groups of samples from the same distribution.

Results

Integrated Analysis of DNA Copy Number and Gene Expression

We enriched tumor cells by macrodissecting samples from 34 patients with prostate cancer who had castration-resistant progressive disease and five human CRPC tumors derived thereof and grown in murine xenografts. Genomic DNA was subjected to whole-genome array CGH in 39 CRPC (34 surgical and five xenograft) and four hormone-sensitive prostate cancer samples, with transcriptomic profiling of total RNA performed in 25 CRPC samples. The raw data are submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; GSE33277).

Many oncogenic target genes are overexpressed at the transcript level and amplified at the DNA level. A bioinformatics analysis of our transcriptome profiling data of adenocarcinoma CRPC identified 711 up-regulated and 5379 down-regulated genes. An array CGH analysis identified 2171 genes showing copy number gain and 4909 genes showing copy number loss. Known genetic changes, such as prostate-specific TMPRSS2-ERG interstitial deletion on chromosome 21 and AR amplification on the X chromosome, were detected. We next determined which genes' expression was associated with copy number alterations. By integrated analysis, we found 34 genes that showed both copy number gain and transcriptomic overexpression. As expected, AR, the prototypical amplified and overexpressed gene in CRPC, was among these genes. We also identified 198 genes that were both deleted and underexpressed at the mRNA level. The top-ranked genes, including some known target genes and many unexplored genes, are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genes Affected by Copy Number and Expression Alterations

| Up-regulated and amplified genes (n = 34) | Down-regulated and deleted genes (n = 198) |

|---|---|

| AR, ASNS, BOP1, C20orf20, CANT1, CCDC78, CELSR3, CLDN3, DOCK4, DVL1, EDA, EEF1D, EPPK1, EZH2, FABP5, FASN, FBXL6, HIP1, HLTF, KSR2, LRRC14, ORAI2, PDIA2, PHF8, PRKAG2, PRKAR2A, PTK6, PYCRL, RHPN1, SLC26A6, STMN2, WDSOF1, ZNF707, ZP3 | ABHD13, ACTA2, ADAD2, ADAM32, ADAM7, ADAMDEC1, ADAMTS18, ADRA1A, ADRB3, AJ291678, AJ412029, AK056689, AK098579, ANKRD11, ARHGEF15, ATP9B, BC043547, BCMO1, BLK, BRUNOL4, C10orf59, C13orf1, C13orf18, C6orf159, C6orf165, CCBE1, CD180, CDADC1, CES7, CLN5, CNDP1, CNR1, CNTNAP4, COMMD6, CSNK1A1L, CYBA, CYP2C9, DAOA, DCT, DCTN6, DEFA4, DEFA5, DEFA6, DEFB1, DEFB4, DGKH, DHRS12, DLEU7, DLGAP2, DYNLRB2, EBF2, EDNRB, EGR3, ELF1, EPHX2, EPSTI1, EXOC6, EXTL3, FAM124A, FAM3B, FGF17, FGF20, FGL1, FHOD3, FLJ22167, FLJ37543, FUT10, FUT9, GABARAPL2, GABRR1, GALR1, GFRA2, GLP2R, GNAO1, GOT2, GPR63, GRIK2, HDDC2, HPSE2, HS3ST3A1, HS3ST3B1, HS3ST5, HTR1A, HTR1E, IFIT2, IGSF5, ITM2B, KCNG4, KCTD9, KIAA0513, KIAA1704, KIF13B, KLF5, KLHL32, LDB3, LDHD, LETM2, LGI3, LIX1, LPCAT2, LRIT1, LRP1B, MAF, MAP1LC3B, MC4R, MCHR2, ME1, MFHAS1, MIER3, MLNR, MX1, MYO16, MYOCD, NAT1, NAT2, NDFIP2, NEFL, NEFM, NETO1, NKAIN2, NRG1, NT5E, NTN1, NUDT15, NUDT7, ODF4, OLFM4, OPN4, OR4K1, PABPC4L, PCDH10, PCDH8, PCDH9, PCP4, PDLIM2, PEBP4, PIBF1, PIK3C2G, PIK3R6, PIWIL2, PKD1L2, PLEKHA2, PLEKHA5, PMFBP1, PNMA2, PNOC, PPAPDC1B, PPP1R3C, PPP2CB, PRDM13, PRDM7, PTCD2, PTEN, RAD17, RAX, RCBTB2, RIOK2, RTTN, SCARA5, SCEL, SEC63, SERP2, SERPINB11, SERPINB13, SERPINB3, SERPINB5, SERPINB7, SFTPC, SH3BGR, SLC16A12, SLC18A1, SLC35A1, SLC6A2, SMAD9, SOHLH2, SOX7, SPACA1, SPG20, STAR, STMN4, SUCLA2, TAT, THSD7B, TMEM174, TMEM66, TNFRSF10C, TNFRSF10D, TNKS, TRIM23, TUSC3, UNC5D, WBP4, WDR16, WISP3, ZC3H13, ZDHHC2, ZFP1, ZNF516 |

Identification and Independent Validation of ASNS as a Candidate Gene

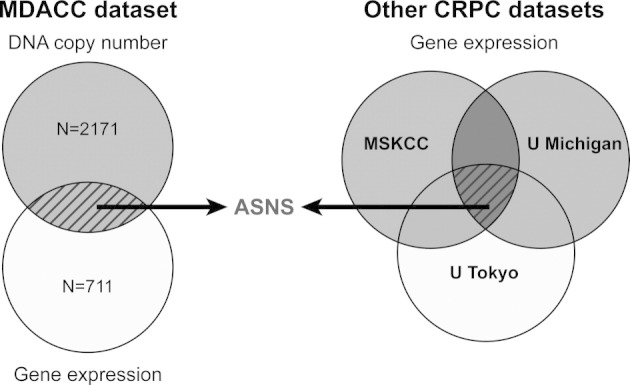

We accumulated a relatively large sample size of CRPC in this study, but the number was still small compared with the variables being measured in genomic studies. To further reduce false positives, we performed an in silico analysis of publicly available gene expression data in CRPC to validate our candidates using independent data sets. An authentic meta-analysis was challenging because public CRPC data are derived from tissues that have been procured using distinct methods, from various anatomical sites, and using different epithelial cell isolation methods and profiled using different platforms. Despite these limitations, we chose only those data sets that could be normalized to benign prostatic tissues, as we did with our samples, thus allowing for a more direct comparison with our own data.

We focused on those candidates that were up-regulated at the DNA copy number and RNA expression levels in our data set and compared them with the CRPC gene expression profiling data from three other institutions: Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (GSE21032), University of Michigan (GDS1439), and University of Tokyo (GSE6811) (available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). The results of the comparative analysis are shown in Figure 1. ASNS was prioritized for further study because it was identified in our integrative genomic analysis and was overexpressed in all three other CRPC data sets.

Figure 1.

ASNS identification using integrative and in silico analyses. The combination of up-regulated DNA copy number and mRNA gene expression was used to derive a list of candidates that were externally validated against other CRPC gene expression data sets. MSKCC, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; U Michigan, University of Michigan; U Tokyo, University of Tokyo.

Augmented ASNS at DNA, mRNA, and Protein Levels Is Associated with Prostate Cancer Progression

We compared normalized expression data from our CRPC adenocarcinoma cases with those from untreated hormone-sensitive prostate carcinoma from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (GSE21032, n = 108) and found ASNS to be among the most overexpressed genes (P = 1.0 × 10−16) in localized CRPC. ASNS was, likewise, up-regulated, with progression to metastatic CRPC within the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center cohort (P = 4.03 × 10−5) (see Supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

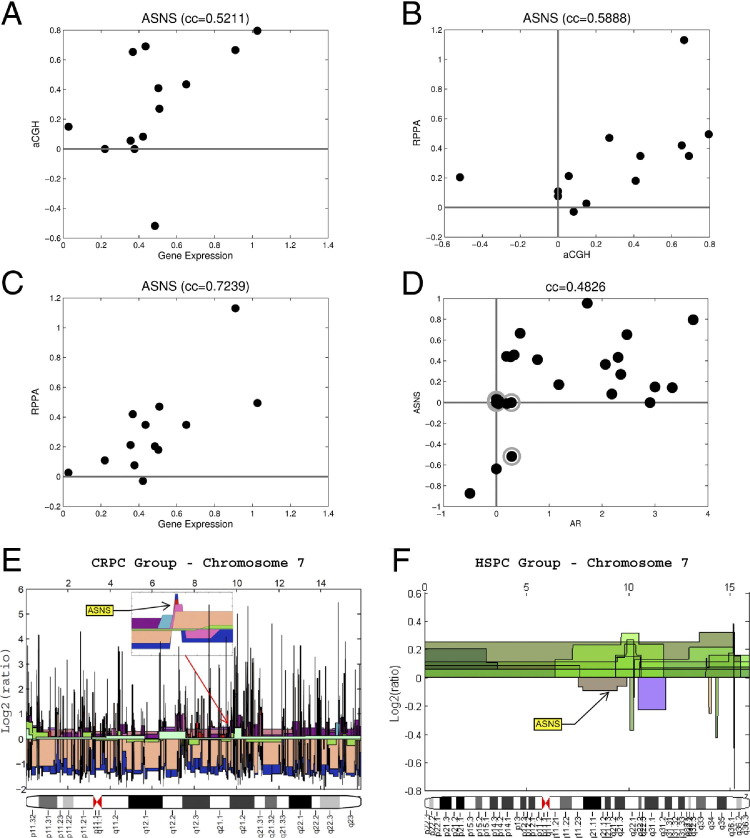

Analysis of our genomic data showed that the ASNS gene copy number was correlated with its mRNA expression (r = 0.5211). We next determined whether ASNS protein was elevated. By using RPPA to evaluate the proteome in the same 25 frozen samples from which we derived our transcriptomic data, we found ASNS protein expression to be strongly correlated with its DNA copy number (r = 0.5888) and mRNA expression (r = 0.7239). Moreover, ASNS DNA copy number was correlated with that of AR (r = 0.4826), suggesting growth of tumor clones harboring amplification of both genes in castration-resistant disease (Figure 2, A–D).

Figure 2.

ASNS copy number is up-regulated in CRPC and is tightly correlated to its transcript and protein levels. Correlation of ASNS DNA copy number with mRNA (A) and protein (B) expression. C: ASNS mRNA correlation with protein expression. D: DNA copy number correlation of ASNS and AR. Chromosome 7 with the subfigure used to visualize the ASNS gene in our CRPC samples. The ASNS copy number values in all samples were larger than the threshold of 0.4. E: Different samples are shown using different colors. F: Hormone-sensitive prostate cancers from the Stanford data set (n = 45), showing ASNS copy number values in all samples <0.4 threshold. aCGH, array comparative genomic hybridization; cc, correlation co-efficient (Pearson); HSPC, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

To determine whether the genetic change in ASNS was associated with progression to a therapy-resistant state, we compared ASNS copy numbers in our cohort of CRPC against public DNA copy number data from hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (Stanford data set, GSE6469). We visualized chromosome 7 in all our CRPC samples in Figure 2E and in 45 samples from the Stanford data set in Figure 2F. As illustrated, ASNS shows DNA copy number gain with prostate cancer progression from a hormone-sensitive to a castration-resistant state. The ASNS values in all hormone-sensitive samples are smaller than the threshold of 0.4 (ie, the values are close to normal). We also found a normal ASNS DNA copy number in our hormone-sensitive prostate cancers, with up-regulation in CRPC-chemotherapy–naïve (31%) and CRPC-chemotherapy–treated (43%) tumors.

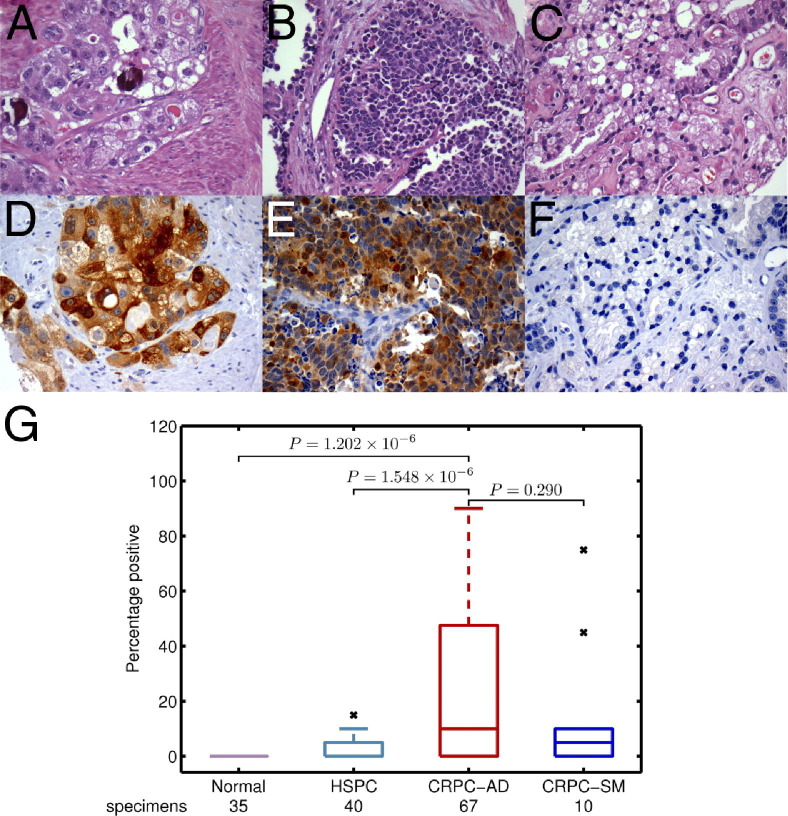

Because more CRPC samples are available as formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks, we detected ASNS protein expression by IHC analysis on multiple TMAs comprising 77 castration-resistant and 40 untreated hormone-sensitive prostate cancer tumors. ASNS positivity, evaluated semiquantitatively, was significantly higher in castration-resistant tumors than in hormone-sensitive untreated prostate cancer (P = 1.548 × 10−6) and normal prostate (P = 1.202 × 10−6) (Figure 3). A box plot of the different study groups used to compute the SDs is shown in Figure 3. Both major morphological variants of CRPC, adenocarcinoma, and small-cell carcinoma expressed ASNS, with no significant difference between these two groups (P = 0.290).

Figure 3.

Increased immunohistochemical expression of ASNS with clinical progression of prostate cancer. H&E-stained sections showing castration-resistant adenocarcinoma (A), castration-resistant small-cell carcinoma (B), and hormone-sensitive high-grade prostate carcinoma (C) and ASNS immunostaining of these samples (D–F, respectively), with relative immunoexpression of different groups (G). The x denotes outlier data points.

Silencing of ASNS in Asparagine-Deprived Media of Prostate Cancer Cell Lines and ex Vivo Xenografts Induces Tumor Growth Inhibition

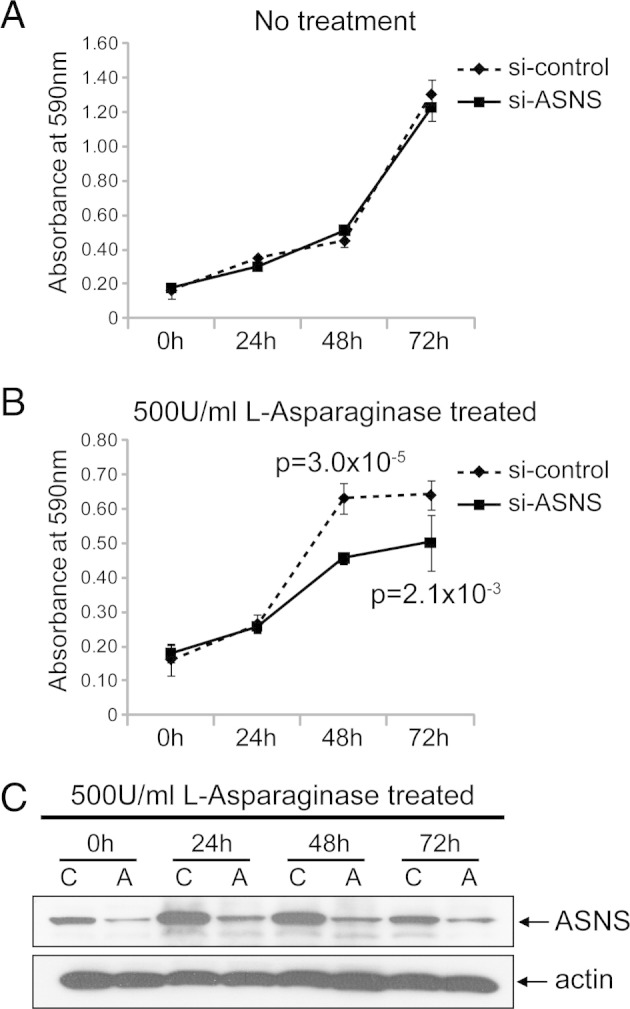

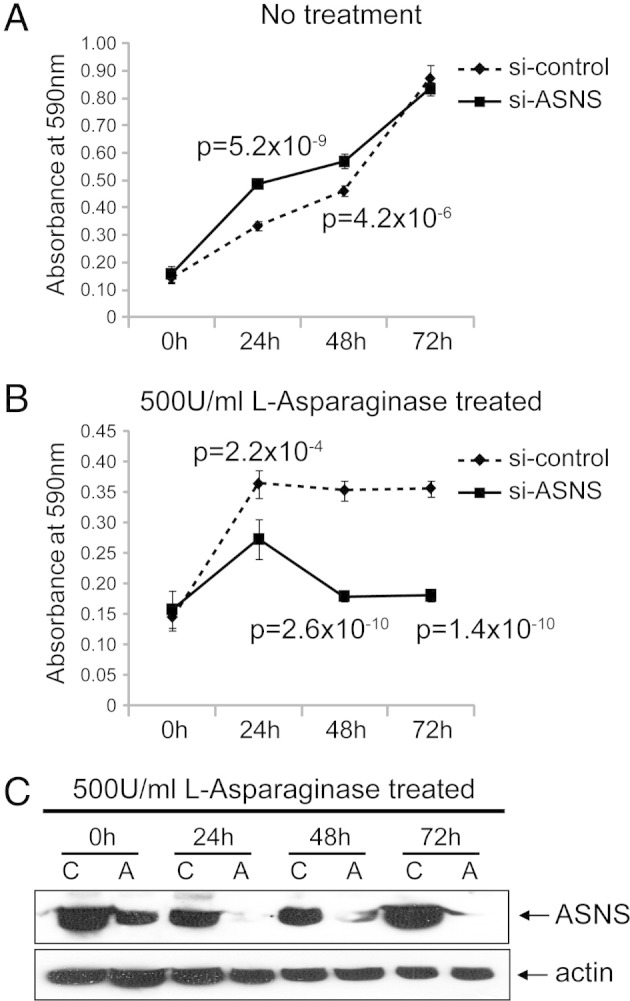

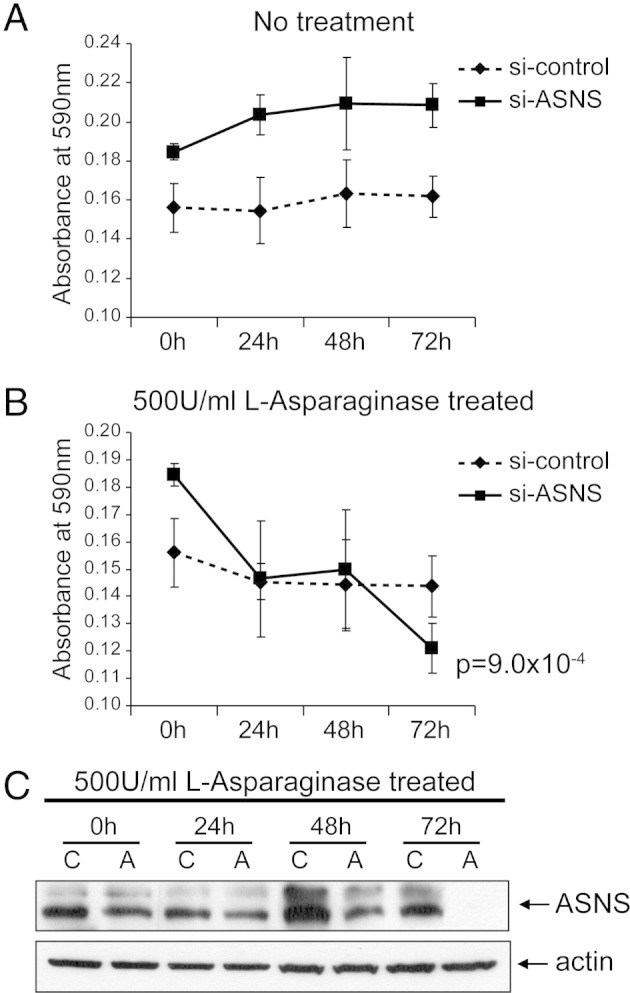

The previous integrated analysis of genomic and proteomic data, coupled with IHC analysis of clinically annotated tissue arrays, provided supporting evidence that ASNS is an augmented signal in CRPC. Because it is a potential target and biomarker for other cancer types, such as pancreatic20 and ovarian cancers,21 we sought additional cell-based evidence that it was a therapeutic target for prostate cancer. We evaluated its functional role using siRNA to lower ASNS expression in hormone-sensitive LNCaP and castration-resistant C4-2B prostate cancer cell lines. ASNS protein knockdown was achieved in both cell lines, as demonstrated by using Western blot analysis (Figure 4, Figure 5). To control for off-target effects, we used mock siRNA and an siRNA against an unrelated gene. Pooled siRNA was used against our target because it is advantageous with respect to greater penetrance and reduced off-target effects compared with individual siRNA.22, 23 We then performed an MTT proliferation assay of control and ASNS-silenced cell lines. Because ASNS catalyzes the formation of the nonessential amino acid asparagine, which is present in cell culture media, we also treated media with 500 U of l-asparaginase. siRNA ASNS inhibited the growth of both LNCaP and C4-2B cell lines (LNCaP: 72 hours, P = 1.4 × 10−10; C4-2B: 72 hours, P = 2.1 × 10−3) only in l-asparaginase–treated media. ASNS-silenced cells without concomitant l-asparaginase drug treatment did not show significant growth inhibition compared with the control. Moreover, l-asparaginase treatment without ASNS knockdown had no growth-inhibitory effect. Together, our results suggest that ASNS's functional effect is mediated via asparagine levels, in that asparagine present in the culture medium provides cells with an extracellular source of asparagine to compensate for intracellular ASNS knockdown.

Figure 4.

Cell viability of C4-2B cells after siRNA knockdown of ASNS. MTT cell growth assays were performed after different incubation time periods, as indicated. The plots for the no treatment (A) and 500 U/mL of l-asparaginase-treated (B) groups represent data from a mean absorbance of 590 nm from six wells for each time point. The error bars represent the SDs (n = 6). si-control, control siRNA. C: Western blot analysis to evaluate the performance of si-ASNS in C4-2B cells. Whole cell lysates from C4-2B cells were collected at different time points, as indicated. Protein (30 μg) from each sample was used and blotted with ASNS antibody. The blot was reprobed with β-actin as the loading control. A, si-ASNS; C, control siRNA.

Figure 5.

Cell viability of LNCaP cells after siRNA knockdown of ASNS. MTT cell growth assays. The experiments and MTT assays were performed in a similar manner to that described in Figure 4, except LNCaP cells were used. The plots for the no treatment (A) and 500 U/mL of l-asparaginase-treated (B) groups represent data from a mean absorbance of 590 nm from six wells for each time point. si-control, control siRNA. C: Western blot analysis to evaluate the performance of si-ASNS in LNCaP cells was performed in a similar manner to that described in the legend to Figure 4C. A, si-ASNS; C, control siRNA.

A similar strategy to that previously described was used to evaluate the ex vivo growth of MDA 180-30 prostate cancer cells derived from a castration- and chemotherapy-resistant patient who underwent palliative cystoprostatectomy. As shown in Figure 6, ASNS knockdown in asparagine-deprived media resulted in cellular growth inhibition (MDA 180-30: 72 hours, P = 0.0009) between the 48- and 72-hour time point.

Figure 6.

Cell viability of ex vivo CRPC xenograft after siRNA knockdown of ASNS. MTT cell growth assays. PCA 180-30 cells (0.7 million) from primary cultures (see Materials and Methods) were seeded into each well of a six-well plate. After 48 hours of incubation, the cells were transfected with control siRNA (si-control) or si-ASNS. At 24 hours after transfection, the cells were trypsinized, and 4000 cells in 100 μL of complete medium were seeded into each well of a 96-well plate. These cells were continually incubated for 48 hours, followed by no treatment (A) and l-asparaginase treatment (B). The treatments and MTT assays were performed as described in the legend to Figure 4. C: Western blot analysis to evaluate the performance of si-ASNS in PCA 180-30 cells. The cells were treated in the same manner as those described in the legend to Figure 4, and the Western blot analysis was performed as described in the legend to Figure 4C.

Discussion

We have used integrative molecular profiling with in silico validation to identify ASNS as a candidate gene that shows both DNA copy number gain and mRNA overexpression in CRPC. Genomic DNA gain, which was tightly correlated with ASNS protein expression (as detected by quantitative RPPA), appeared to be an important mechanism for ASNS overexpression during prostate cancer's transition from the untreated, hormone-sensitive state to the castration- and chemotherapy-resistant state. IHC expression of ASNS protein was also associated with progression to a treatment-refractory state in TMAs that included 117 localized and metastatic clinical prostate cancer cases.

Our genomic and clinical data suggest that ASNS DNA copy number gain and consequent protein overexpression may be selected for during prostate cancer progression to a therapy-resistant state. Although previous investigators24, 25, 26, 27, 28 had found overall chromosome 7 copy number gain to be associated with poor prognosis in untreated prostate cancer, our analysis showed DNA copy number gain of the specific 7q21region mapping to the ASNS gene with progression to castration resistance (Figure 2, E and F). Prior integrative molecular profiling studies in CRPC are sparse and have not specifically pursued ASNS as a target,29, 30, 31 although the 7q21 region harboring the ASNS gene fell within an area of high-frequency copy number gain.31

Increased ASNS, which normally catalyzes formation of the amino acid asparagine from aspartate,32 can be induced by glucose-deprived conditions; this has been shown in pancreatic cancer cells, in which ASNS is thought to act by an anti-apoptotic mechanism.20 As neoplastic cells acquire greater metabolic needs and experience relative nutrient deprivation, their ASNS levels may increase through increased DNA copy number to effect a cell survival program. Because not all tumors with overexpressed ASNS show concordant DNA copy number gain, mechanisms other than DNA copy number alteration are likely involved in its up-regulation. For example, ASNS overexpression is mediated by binding mutated p53 to the ASNS promoter.33 Given the increased prevalence of mutated p53 in advanced CRPC,34, 35 this mechanism may also contribute to ASNS overexpression.

ASNS's functional importance in prostate cancer is supported by our finding of cellular growth inhibition, with ASNS silencing, in hormone-sensitive and CRPC cell lines. Our cell line data are buttressed by ASNS siRNA-mediated cellular growth inhibition in a prostate cancer xenograft model derived from a castration- and chemotherapy-resistant tumor. Depleting cancer cells of the nonessential amino acid asparagine is a rational therapeutic modality that has been used for >35 years in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia.36 In acute lymphoblastic leukemia, cellular and plasma asparagine levels are reduced using l-asparaginase therapy, which hydrolyzes conversion of asparagine to aspartate. l-Asparaginase treatment has traditionally been most effective in leukemic cells, which produce low levels of endogenous asparagine because of low basal levels of ASNS. More recently, asparagine depletion strategies have been suggested in pancreatic and ovarian cancers20, 21 using ASNS inhibitors and asparaginase, respectively. New-generation inhibitors of ASNS36 allow for levels of this enzyme to be reduced to trace levels. Given the relative glucose and asparagine amino acid deficiency that exists in metabolically active advanced tumors, such as CRPC, and that presumably leads to ASNS up-regulation, ASNS inhibitors may be used alone to effect further asparagine depletion and sensitize neoplastic cells to apoptotic cell death. Combinatorial strategies using ASNS inhibitors paired with l-asparaginase, which have recently been patented to treat hematological and solid tumors,37 may also be useful. Although this is the first report, to our knowledge, of asparagine deprivation in prostate cancer, other single amino acid deprivation strategies, such as anti-arginine therapy, have been reported to cause metabolic stress-induced prostate cancer cell death.38

In summary, we used integrated genomic analysis to identify ASNS as a potential target in terminal prostate cancer. Although ASNS up-regulation is associated with castration-resistant disease in patient samples, we found that asparagine-deprivation strategies can inhibit growth in hormone-sensitive (LNCaP), castration-resistant, chemotherapy-naïve (C4-2B) and castration-resistant, and chemotherapy-resistant (MDA 180-30) cell lines and xenografts. Subsequent studies should use biological model systems that more closely approximate human prostate cancer. It would also be of interest to determine whether metabolic treatment modalities, such as amino acid (eg, asparagine) deprivation, can synergize with established antimitotic taxane-based chemotherapies in prostate cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ina N. Prokhorova, Ana L. Garcia, Anh Hoang, Kim-Anh Vu, Haidee Chancoco, Yiling Lu, Mireya Guerrero, and Ann Sutton for technical and secretarial assistance and Ping Liu for help in statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Supported in part by institutional funds from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (K.S.). Proteomic data were generated using the Biospecimen Extraction and RPPA core facilities at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. These facilities are funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA 16672).

Author Contributions: K.S., H.H., P.T., N.N., and W.Z. conceived the experiments and analyzed data; K.S., J.D., V.T., E.E., I.H.K., F.S., T.A.B., and A.A. were involved in study design and data collection; and L.H., D.C., J.D., and D.L. performed the experiments. All authors were involved in writing the article and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.030.

Contributor Information

Kanishka Sircar, Email: ksircar@mdanderson.org.

Wei Zhang, Email: wzhang@mdanderson.org.

Supplementary data

Representative photomicrograph of murine xenograft MDA PCa 180-30 derived from a CRPC parent tumor and used for ex vivo studies. The arrowhead indicates a minor population of mouse stroma amid human parent epithelial tumor cells.

ASNS shows transcriptomic up-regulation in localized CRPC (P = 1.0 × 10−16) (A) and metastatic CRPC (P = 4.03 × 10-5) (B) compared with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

References

- 1.Jemal A., Siegel R., Xu J., Ward E. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrylak D.P., Tangen C.M., Hussain M.H., Lara P.N., Jr, Jones J.A., Taplin M.E., Burch P.A., Berry D., Moinpour C., Kohli M., Benson M.C., Small E.J., Raghavan D., Crawford E.D. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tannock I.F., de Wit R., Berry W.R., Horti J., Pluzanska A., Chi K.N., Oudard S., Theodore C., James N.D., Turesson I., Rosenthal M.A., Eisenberger M.A. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid A.H., Attard G., Barrie E., de Bono J.S. CYP17 inhibition as a hormonal strategy for prostate cancer. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5:610–620. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran C., Ouk S., Clegg N.J., Chen Y., Watson P.A., Arora V., Wongvipat J., Smith-Jones P.M., Yoo D., Kwon A., Wasielewska T., Welsbie D., Chen C., Higano C.S., Beer T.M., Hung D.T., Scher H.I., Jung M., Sawyers C.L. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sircar K., Yoshimoto M., Monzon F.A., Koumakpayi I.H., Katz R.L., Khanna A., Alvarez K., Chen G., Darnel A.D., Aprikian A.G., Saad F., Bismar T.A., Squire J.A. PTEN genomic deletion is associated with p-Akt and AR signalling in poorer outcome, hormone refractory prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2009;218:505–513. doi: 10.1002/path.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulholland D.J., Tran L.M., Li Y., Cai H., Morim A., Wang S., Plaisier S., Garraway I.P., Huang J., Graeber T.G., Wu H. Cell autonomous role of PTEN in regulating castration-resistant prostate cancer growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Q., Jernigan D., Zhang Y., Fatatis A. Implication of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha in prostate cancer skeletal metastasis. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:612–619. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandran U.R., Ma C., Dhir R., Bisceglia M., Lyons-Weiler M., Liang W., Michalopoulos G., Becich M., Monzon F.A. Gene expression profiles of prostate cancer reveal involvement of multiple molecular pathways in the metastatic process. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varambally S., Yu J., Laxman B., Rhodes D.R., Mehra R., Tomlins S.A., Shah R.B., Chandran U., Monzon F.A., Becich M.J., Wei J.T., Pienta K.J., Ghosh D., Rubin M.A., Chinnaiyan A.M. Integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of prostate cancer reveals signatures of metastatic progression. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ylipää A., Hunt K.K., Yang J., Lazar A.J., Torres K.E., Lev D.C., Nykter M., Pollock R.E., Trent J., Zhang W. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117:380–389. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J., Cogdell D., Yang D., Hu L., Li H., Zheng H., Du X., Pang Y., Trent J., Chen K., Zhang W. Deletion of the WWOX gene and frequent loss of its protein expression in human osteosarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2010;291:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price N.D., Trent J., El-Naggar A.K., Cogdell D., Taylor E., Hunt K.K., Pollock R.E., Hood L., Shmulevich I., Zhang W. Highly accurate two-gene classifier for differentiating gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyosarcomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3414–3419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611373104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen N., Huang H., Oraintara S., Vo A. Stationary wavelet packet transform and dependent laplacian bivariate shrinkage estimator for array-CGH data smoothing. J Comput Biol. 2010;17:139–152. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2009.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iadevaia S., Lu Y., Morales F.C., Mills G.B., Ram P.T. Identification of optimal drug combinations targeting cellular networks: integrating phospho-proteomics and computational network analysis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6704–6714. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efstathiou E., Troncoso P., Wen S., Do K.A., Pettaway C.A., Pisters L.L., McDonnell T.J., Logothetis C.J. Initial modulation of the tumor microenvironment accounts for thalidomide activity in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1224–1231. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thalmann G.N., Anezinis P.E., Chang S.M., Zhau H.E., Kim E.E., Hopwood V.L., Pathak S., von Eschenbach A.C., Chung L.W. Androgen-independent cancer progression and bone metastasis in the LNCaP model of human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2577–2581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z.G., Mathew P., Yang J., Starbuck M.W., Zurita A.J., Liu J., Sikes C., Multani A.S., Efstathiou E., Lopez A., Wang J., Fanning T.V., Prieto V.G., Kundra V., Vazquez E.S., Troncoso P., Raymond A.K., Logothetis C.J., Lin S.H., Maity S., Navone N.M. Androgen receptor-negative human prostate cancer cells induce osteogenesis in mice through FGF9-mediated mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2697–2710. doi: 10.1172/JCI33093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jabbur J.R., Zhang W. p53 Antiproliferative function is enhanced by aspartate substitution at threonine 18 and serine 20. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:277–283. doi: 10.4161/cbt.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui H., Darmanin S., Natsuisaka M., Kondo T., Asaka M., Shindoh M., Higashino F., Hamuro J., Okada F., Kobayashi M., Nakagawa K., Koide H. Enhanced expression of asparagine synthetase under glucose-deprived conditions protects pancreatic cancer cells from apoptosis induced by glucose deprivation and cisplatin. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3345–3355. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenzi P.L., Reinhold W.C., Rudelius M., Gunsior M., Shankavaram U., Bussey K.J., Scherf U., Eichler G.S., Martin S.E., Chin K., Gray J.W., Kohn E.C., Horak I.D., Von Hoff D.D., Raffeld M., Goldsmith P.K., Caplen N.J., Weinstein J.N. Asparagine synthetase as a causal, predictive biomarker for L-asparaginase activity in ovarian cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2613–2623. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons B.D., Schindler A., Evans D.H., Foley E. A direct phenotypic comparison of siRNA pools and multiple individual duplexes in a functional assay. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kittler R., Surendranath V., Heninger A.K., Slabicki M., Theis M., Putz G., Franke K., Caldarelli A., Grabner H., Kozak K., Wagner J., Rees E., Korn B., Frenzel C., Sachse C., Sonnichsen B., Guo J., Schelter J., Burchard J., Linsley P.S., Jackson A.L., Habermann B., Buchholz F. Genome-wide resources of endoribonuclease-prepared short interfering RNAs for specific loss-of-function studies. Nat Methods. 2007;4:337–344. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barranco M.A., Alcaraz A., Corral J.M., Sole M., Mallofre C., Llopis J., Rodriguez A., Ribal M.J., Alvarez-Vijande R., Carretero P. Numeric alterations in chromosomes 7 and 8 detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization correlate with high-grade localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 1998;34:419–425. doi: 10.1159/000019776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skacel M., Ormsby A.H., Pettay J.D., Tsiftsakis E.K., Liou L.S., Klein E.A., Levin H.S., Zippe C.D., Tubbs R.R. Aneusomy of chromosomes 7, 8, and 17 and amplification of HER-2/neu and epidermal growth factor receptor in Gleason score 7 prostate carcinoma: a differential fluorescent in situ hybridization study of Gleason pattern 3 and 4 using tissue microarray. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:1392–1397. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.29676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alcaraz A., Takahashi S., Brown J.A., Herath J.F., Bergstralh E.J., Larson-Keller J.J., Lieber M.M., Jenkins R.B. Aneuploidy and aneusomy of chromosome 7 detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization are markers of poor prognosis in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3998–4002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandyk M.G., Zhao L., Troncoso P., Pisters L.L., Palmer J.L., von Eschenbach A.C., Chung L.W., Liang J.C. Trisomy 7: a potential cytogenetic marker of human prostate cancer progression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;9:19–27. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870090105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visakorpi T., Kallioniemi A.H., Syvanen A.C., Hyytinen E.R., Karhu R., Tammela T., Isola J.J., Kallioniemi O.P. Genetic changes in primary and recurrent prostate cancer by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res. 1995;55:342–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J.H., Dhanasekaran S.M., Mehra R., Tomlins S.A., Gu W., Yu J., Kumar-Sinha C., Cao X., Dash A., Wang L., Ghosh D., Shedden K., Montie J.E., Rubin M.A., Pienta K.J., Shah R.B., Chinnaiyan A.M. Integrative analysis of genomic aberrations associated with prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8229–8239. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor B.S., Schultz N., Hieronymus H., Gopalan A., Xiao Y., Carver B.S., Arora V.K., Kaushik P., Cerami E., Reva B., Antipin Y., Mitsiades N., Landers T., Dolgalev I., Major J.E., Wilson M., Socci N.D., Lash A.E., Heguy A., Eastham J.A., Scher H.I., Reuter V.E., Scardino P.T., Sander C., Sawyers C.L., Gerald W.L. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holcomb I.N., Young J.M., Coleman I.M., Salari K., Grove D.I., Hsu L., True L.D., Roudier M.P., Morrissey C.M., Higano C.S., Nelson P.S., Vessella R.L., Trask B.J. Comparative analyses of chromosome alterations in soft-tissue metastases within and across patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7793–7802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richards N.G., Schuster S.M. Mechanistic issues in asparagine synthetase catalysis. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1998;72:145–198. doi: 10.1002/9780470123188.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scian M.J., Stagliano K.E., Deb D., Ellis M.A., Carchman E.H., Das A., Valerie K., Deb S.P., Deb S. Tumor-derived p53 mutants induce oncogenesis by transactivating growth-promoting genes. Oncogene. 2004;23:4430–4443. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osman I., Drobnjak M., Fazzari M., Ferrara J., Scher H.I., Cordon-Cardo C. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in prostate cancer: impact on tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2082–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes J.H., Cohen M.B., Robinson R.A. p53 Immunoreactivity in primary and metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 1995;8:462–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richards N.G., Kilberg M.S. Asparagine synthetase chemotherapy. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:629–654. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorenzi P.L., Weinstein J.N., Caplen N.J. Materials and Methods Directed to Asparagine Synthetase and Asparaginase Therapies. U.S. Patent US20090311233. Dec. 17, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim R.H., Coates J.M., Bowles T.L., McNerney G.P., Sutcliffe J., Jung J.U., Gandour-Edwards R., Chuang F.Y., Bold R.J., Kung H.J. Arginine deiminase as a novel therapy for prostate cancer induces autophagy and caspase-independent apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:700–708. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Representative photomicrograph of murine xenograft MDA PCa 180-30 derived from a CRPC parent tumor and used for ex vivo studies. The arrowhead indicates a minor population of mouse stroma amid human parent epithelial tumor cells.

ASNS shows transcriptomic up-regulation in localized CRPC (P = 1.0 × 10−16) (A) and metastatic CRPC (P = 4.03 × 10-5) (B) compared with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.