Abstract

Background: Body mass index (BMI) in childhood predicts obesity in adults, but it is unknown whether rapid increase and variability in BMI during childhood are independent predictors of adult obesity.

Methods: The study cohort consisted of 1622 Bogalusa Heart Study participants (aged 20 to 51 years at follow-up) who had been screened at least four times during childhood (aged 4–19 years). BMI rate of change during childhood for each individual was assessed by mixed models; BMI residual standard deviation (RSD) during childhoodwas used as a measure of variability. The average follow-up period was 20.9 years.

Results: One standard deviation increase in rate of change in BMI during childhood was associated with 1.39 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.17–1.61] kg/m2 increase in adult BMI and 2.98 (95% CI: 2.42–3.56) cm increase in adult waist circumference, independently of childhood mean BMI. Similarly, one standard deviation increase in RSD in BMI during childhood was associated with 0.46 (95% CI: 0.23–0.69) kg/m2 increase in adult BMI and 1.42 (95% CI: 0.82–2.02) cm increase in adult waist circumference. Odds ratio for adult obesity progressively increased from the lowest to the highest quartile of BMI rate of change or RSD during childhood (P for trend < 0.05 for both).

Conclusions: Rapid increase and greater variability in BMI during childhood appear to be independent risk factors for adult obesity. Our findings have implications for understanding body weight regulation and obesity development from childhood to adulthood.

Keywords: Obesity, variability, rate of change, longitudinal analysis

Key Messages

Childhood body mass index predicts obesity measures in adult life.

Rapid increase in body mass index during childhood predicts obesity measures in adult life, independently of mean body mass index levels in childhood.

Variability in body mass index during childhood predicts obesity measures in adult life, independently of mean body mass index levels in childhood.

Introduction

Obesity is a major public health challenge due to its high prevalence,1 its importance as a major risk factor for many chronic diseases2 and the magnitude of its association with mortality.3,4 The challenge of successfully reversing obesity once established and maintaining weight loss over the long term is well known. Preventionof obesity would have a significant impact in addressing our current worldwide obesity epidemic5 and the associated growing chronic disease burden.6,7 To achieve this goal, it is important to identify risk factors in early life for obesity.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that overweight and obesity tend to have their origin in childhood and track into adulthood.8–13 Consequently, overweight and obese children are more likely to become obese adults with a higher risk of obesity-associated diseases. Studies have also shown that rapid weight gain during infancy and early adiposity rebound (before the age of 6 years) are predictive of adult obesity.12,14–17 However, it is not clear whether rapid weight gain at a later stage during childhood is also a risk factor for adult obesity. Further, body weight variability or fluctuation during adult life has been associated with a higher risk of obesity and related morbidity and mortality,18–23 although intentional weight loss, even not maintained, may have long-term beneficial effects.24,25 It is unknown whether weight variability during childhood, beyond that due to growth and development, is associated with adult obesity. No previous studies have simultaneously examined the effect of rapid weight gain and the effect of weight variability during childhood on adult obesity measures. Exploring the associations of rapid weight gain at a later stage, and weight variability during childhood, with adult obesity risk could enhance our understanding of body weight regulation and energy homeostasis in childhood and have implications for early prevention and intervention.

With data from the Bogalusa Heart Study (BHS), a community-based, Black–White cohort study beginning in childhood, we aimed to examine the associations of rate of change and variability of body mass index (BMI) during childhood (from early school age) with risk of obesity later in life.

Methods

Study population

The BHS, beginning in 1973 and conducted in Bogalusa (65% Whites and 35% Blacks), Louisiana, is a long-term epidemiological study on the natural history of atherosclerosis. Between 1973 and 2010, 9 BHS cross-sectional surveys were conducted in children and adolescents aged 4–19 years, and 10 BHS surveys were conducted in adults aged 20–51 years who had participated in earlier BHS surveys as children. Based on these surveys, we included those who: (i) had been examined at least four times during childhood (aged 4–19 years) and at least once as adult (aged 20–51 years); (ii) had no missing values for all study variables except for waist circumference; and (iii) had BMI z-scores during childhood within 99% of the BMI distribution according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts.26 In total, 1622 participants met these criteria (n = 1,568 for waist circumference). The average period of follow-up was 20.9 years (range: 5.9–41.9 years; median: 21.8 years).

All of the adults in this study provided informed consent at each examination, and consent of a parent/guardian was obtained for those under 20 years of age. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tulane University Health Sciences Center.

Examinations

All of the examinations during the above surveys used an almost identical protocol for risk factor measurements.27 At each study visit, weight in light clothing without shoes was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg on a dedicated scale which was routinely calibrated; height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with a free-standing stadiometer. Height and weight were measured at least twice and the mean value of each of these was used to calculate BMI (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres).28,29 Waist circumference in adults was measured midway between the rib cage and the superior border of the iliac crest twice, to the nearest 0.1 cm by a non-stretchable tape, and the mean value was used in our analysis.30 Information on smoking status (yes/no) was obtained as part of a health habit questionnaire.31

Statistical methods

BMI, waist circumference and obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) at the most recently available BHS adult study visit were used as primary outcome variables; overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) and central obesity (waist circumference ≥ 102 cm for men or ≥ 88 cm for women) were used as secondary outcome variables.

To mitigate the impact of heteroscedasticity of BMI over age, we first log-transformed BMI. Growth curves of log-transformed BMI during childhood were derived for each race and sex group by using a random-effects model with SAS Proc MIXED, as previously described.32,33 Briefly, we fitted three different models that included: (i) age only; (ii) age and its quadratic term; and (iii) age and its quadratic and cubic terms, with both fixed and random effects of the corresponding term(s) considered simultaneously. The fixed coefficients represented fixed population parameters and the random coefficients represented the difference between fixed population parameters and the true values for individuals. The higher-order terms of age would not be included in the model if they were not significant or made lower-order terms not significant. Age was centred by subtracting the mean to minimize collinearity of age with its higher-order terms. We chose the last model which included age and its quadratic and cubic terms because the model had the smallest AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion). Although all three terms of age were used to develop BMI growth curves, we did not evaluate the effects of the quadratic and cubic terms on adult obesity measures for the following two reasons: (i) potential collinearity between the quadratic term and mean BMI (r = –0.75) and between the linear term and the cubic term (r = 0.85); and (ii) complexities in their respective interpretations. The linear change of BMI over age (hence rate of change) during childhood was calculated as the sum of the fixed coefficient and the random coefficient of age for each individual. We used residual standard deviation (RSD)34 to assess BMI variability during childhood for each individual, which was calculated as , where is the observed BMI at time point , is the predicted BMI at time according to the growth curve derived from the mixed model for each individual (i.e. is the residual from the mixed model), and n is the number of data points for BMI during childhood. To compare the effect sizes of rate of change and variability and to facilitate interpretation, we standardized childhood mean BMI, rate of change and RSD for further association analyses.

General linear models were used to examine the associations between rate of change or variability in BMI during childhood and adult BMI and waist circumference, adjusting for childhood mean BMI, race, sex, adulthood age and cigarette smoking. A chi-square test was used to examine the relationship between the rate of change or variability in BMI during childhood and the subsequent prevalence of obesity, overweight or central obesity at the last follow-up. Logistic regression models were used to examine the association between rate of change or variability in BMI during childhood and adult obesity, overweight or central obesity, following adjustment for the same covariates used in the previously described linear regression models. Sensitivity analyses were performed by: (i) using RSD corrected for the mean, which was calculated as RSD divided by the mean value of BMI during childhood, for each participant; (ii) sex- and race-specific (Black-White) analysis; and (iii) excluding those in the top 15% and the bottom 15% of the mean BMI Z-scores to minimize the potential influence of intentional weight change due to high or low body weight status. All data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

At the time of the last study visit in adulthood, the mean age of the participants was 29.7 years and the prevalence of obesity was 29.2% [95% confidence interval (CI): 27.0–31.4%]. Blacks tended to have a higher rate of change in BMI than Whites, and Black females had the greatest variability in BMI during childhood compared with the other three groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohort by race and sex: the Bogalusa Heart Study

| Characteristics | White |

Black |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 449) | Female (n = 529) | Male (n = 263) | Female (n = 381) | |

| Childhood | ||||

| Mean age (years) | 12.7 ± 2.3 | 12.6 ± 2.3 | 13.0 ± 2.1 | 12.8 ± 2.1 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 19.5 ± 3.2 | 19.2 ± 3.0 | 19.4 ± 3.3 | 20.2 ± 3.8 |

| Rate of change in BMIa | 0.039 ± 0.013 | 0.037 ± 0.017 | 0.041 ± 0.013 | 0.047 ± 0.014 |

| RSDa | 0.031 ± 0.018 | 0.035 ± 0.019 | 0.027 ± 0.017 | 0.040 ± 0.021 |

| Adulthood | ||||

| Age (years) | 30.1 ± 6.6 | 29.4 ± 6.0 | 29.2 ± 6.7 | 29.1 ± 6.3 |

| Smoker (%) | 31.1 | 31.8 | 35.8 | 26.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 ± 5.4 | 26.1 ± 6.3 | 27.2 ± 6.2 | 29.1 ± 8.1 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 93.4 ± 13.3 (n = 514) | 80.2 ± 14.5 (n = 427) | 88.6 ± 15.8 (n = 256) | 86.7 ± 17.8 (n = 371) |

Mean ± SDs are shown, except for cigarette smoking.

aLog-transformed BMI.

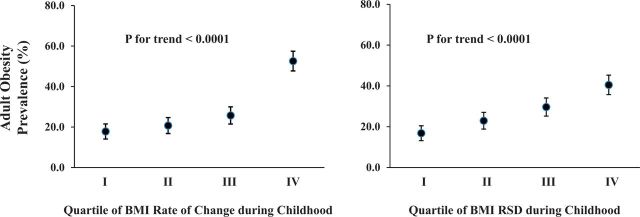

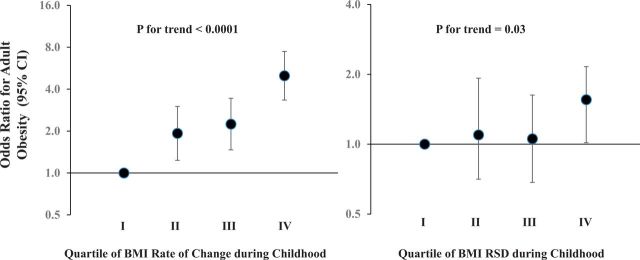

As expected, mean BMI during childhood was positively associated with adult BMI and waist circumference (Table 2). Further, rate of change and RSD in BMI during childhood were also positively associated with adult BMI and waist circumference, independently of adult age, race, sex, cigarette smoking and childhood mean BMI (Table 2). One standard deviation increase in rate of change in BMI during childhood was associated with 1.39 (95% CI: 1.17–1.61) kg/m2 increase in adult BMI and 2.98 (95% CI: 2.42–3.56) cm increase in adult waist circumference, independently of childhood mean BMI. Similarly, one standard deviation increase in RSD in BMI during childhood was associated with 0.46 (95% CI: 0.23–0.69) kg/m2 increase in adult BMI and 1.42 (95% CI: 0.82–2.02) cm increase in adult waist circumference. From the lowest to the highest quartile of BMI rate of change or RSD during childhood, there was a progressive increase in the prevalence of or odds ratio for adult obesity (Figures 1 and 2). Similar results were observed for adult overweight and central obesity (P < 0.01 in all cases).

Table 2.

Associations of mean BMI, rate of change and residual standard deviation during childhood with adult BMI and waist circumference

| Independent variable | Adult BMI (kg/m2) (n = 1622) |

Adult waist circumference (cm) (n = 1568) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient | 95% confidence interval | Regression coefficient | 95% confidence interval | |

| Adult age (year) | 0.23 | 0.20, 0.27 | 0.75 | 0.66, 0.84 |

| Black race | 1.47 | 1.03, 1.91 | 1.70 | 0.56, 2.83 |

| Female gender | −0.16 | −0.59, 0.28 | −8.75 | −9.87, −7.63 |

| Adult cigarette smoking | −2.17 | −2.63, −1.71 | −3.78 | −4.96, −2.60 |

| Mean BMI in childhooda | 4.16 | 3.90, 4.41 | 8.52 | 7.86, 9.17 |

| Rate of change in childhood BMIa | 1.39 | 1.17, 1.61 | 2.98 | 2.42, 3.56 |

| Residual standard deviationin childhood BMIa | 0.46 | 0.23, 0.69 | 1.42 | 0.82, 2.02 |

Adult BMI (or waist circumference) was the dependent variable, with variables in the left column as independent variables.

aStandardized, with regression coefficient representing change in dependent variables for one standard deviation increase.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) in adulthood by quartile of BMI rate of change or of residual standard deviation (RSD) during childhood. P value was from a chi-square test. Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Odds ratio for obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) in adulthood by quartile of BMI rate of change or of residual standard deviation (RSD) during childhood using the lowest quartile as the reference (OR = 1). P value was adjusted for race, sex, childhood mean BMI, adult age, adult cigarette smoking, and BMI RSD/rate of change during childhood. Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

Mean BMI-adjusted RSD also showed associations with adult BMI and waist circumference. Directions of the associations of RSD in BMI during childhood with adult BMI and waist circumference were consistent when stratified by race and sex, although not all reached P < 0.05. Excluding those in the top 15% and the bottom 15% of the mean BMI Z-score during childhood did not change the overall associations (P < 0.001 for rate of change and RSD in all cases).

Discussion

In this community-based, longitudinal cohort, we demonstrated that rapid increase and greater variability in BMI during childhood were associated with increased obesity measures in adulthood, independently of mean BMI during childhood. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate that rapid increase and greater variability in BMI during childhood are independent risk factors for adult obesity.

Mean BMI during childhood was the strongest predictor of adult obesity measures, consistent with previous observations.8–11 Importantly, we also observed an independent association between rate of change in BMI during childhood with adult obesity measures, which extends previous observations that rapid growth during infancy is a risk factor for adult obesity. Taken together, available evidence suggests that rapid increase in BMI in the first two decades of life is a potent risk factor for adult obesity.

No previous studies have examined the association between childhood BMI variability and adult obesity measures. Variability would be expected to increase with progressively higher mean values. However, the associations we observed were independent of the mean value of BMI in childhood because the associations persisted with adjustment for the mean value of BMI during childhood. Fluctuation in weight is associated with obesity and weight change in adults.35,36 Fluctuation in weight during adult life can be confounded by intentional weight loss and regain, repetition of which results in so called ‘weight cycling’.35,37,38 BMI variability during childhood as assessed by RSD that takes into account variability due to growth and development, on the other hand, may result from spontaneous fluctuation rather than from intentional weight manipulation. In the current study, the association between childhood BMI variability and adult obesity measures persisted even after we limited our analysis to a sample that excluded those in the top 15% and bottom 15% of the mean BMI distribution during childhood, suggesting that the associations we observed were unlikely to be confounded by intentional weight change (due to either high or low BMI) during childhood. Taken together, our results suggest that childhood body weight variability may be an important novel risk factor for adult obesity, independent of the absolute values of body weight and its rate of change over time during childhood.

The underlying mechanisms for the observed associations between childhood BMI variability and adult obesity measures are not known. Body weight variability may represent an essential trait that reflects responses or adaptations to changes in the environment. The tendency to change body weight as a result of changes in the environment increases the risk of obesity when the environment favours weight gain. On the other hand, low BMI variability may reflect an individual’s tendency to keep a stable weight even when confronted with an obesogenic environment. Our results provide novel materials for the ongoing discussions on theoretical models to understand the complex interplay between genes and environments in body weight regulation.39

Many, though not all, studies have shown that weight fluctuation in adult life may increase the risk of morbidity and mortality and associated risk factors.20,21,40–44 Body weight variability during childhood is associated with blood pressure variability, a risk factor for hypertension and associated cardiovascular diseases.34 Whether body weight variability, or stability, during childhood is linked to risk of other metabolic traits and diseases warrants further investigation.

Determinants of body weight variability in humans are largely unknown. Genetic factors may play a role in this regard.45 The fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) gene harbours common variants that contribute to BMI variability.45 Additional studies are needed to identify other contributing factors for body weight variability.

Our study has several important strengths. The longitudinal observations during more than 20 years of follow-up from childhood to adulthood make reverse causation a very unlikely possibility. In this community-based study, all of the study participants were screened at least four times during childhood, which allowed for a reliable assessment of BMI rate of change and its variability. In addition, there was a consistent approach to the measurement of weight and height at each study visit, and application of stringent quality control measures. Finally, our study simultaneously assessed the associations of mean BMI, rate of change and variability during childhood with adult obesity measures, which provides a more complete depiction of childhood growth dynamics in predicting adult obesity risk.

Several limitations of the study need to be considered. First, participants included in the study were more likely to be Black and female, which might have caused selection bias. However, the trend of the associations was consistent across the four race and sex groups. Second, we did not have earlier weight measurements before the age of 4 years, which precluded a full analysis beginning from birth. Third, we did not further consider higher-order terms of age due to potential collinearity and complexities of their biological meaning. Fourth, although we are cautiously optimistic regarding generalizability of the results, in view of the community-based nature of our study, we are aware of the race (Black-White) composition of our study sample. Studies in other race/ethnicity populations may be needed to confirm the current findings. Finally, we first derived linear rate of change and variability by using mixed models and then examined their associations with adult obesity measure. This two-stage approach may be subject to potential bias, as suggested by Sayers et al.46

In conclusion, BMI rate of change and variability during childhood appear to be risk factors for adult obesity, independently of BMI levels. Combined with findings from previous studies, findings of the current study suggest that rapid increase in body weight during the first two decades of life is an important risk factor for adult obesity. Results of the current study also suggest that the ability to keep a relatively stable body weight, in line with normal growth and development, during childhood plays an important role in achieving a normal weight in adulthood. Our findings have implications for understanding body weight regulation and obesity development from childhood to adulthood and for early prevention and intervention of obesity.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [5R01ES021724 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Science, 2R01AG016592 from the National Institute on Aging and K12HD043451 (Tulane Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development] and American Heart Association [13SDG14650068].

Acknowledgement

The Bogalusa Heart Study is a joint effort of many investigators and staff members whose contribution is gratefully acknowledged. We especially thank the Bogalusa, LA, school system, and most importantly the children and adults who have participated in this study over many years. We wish to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments.

Conflict of interest: Authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA 2014;311:806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caterson ID, Hubbard V, Bray GA, et al. Prevention Conference VII: Obesity, a worldwide epidemic related to heart disease and stroke: Group III: worldwide comorbidities of obesity. Circulation 2004;110:e476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2211–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia H, Lubetkin EI. Trends in quality-adjusted life-years lost contributed by smoking and obesity. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB. Global obesity: trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2013;9:13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezzati M, Riboli E. Can noncommunicable diseases be prevented? Lessons from studies of populations and individuals. Science 2012;337:1482–87.£ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet 2014; 384: 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eriksson J, Forsen T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C, Barker D. Size at birth, childhood growth and obesity in adult life. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 735–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juhola J, Magnussen CG, Viikari JS, et al. Tracking of serum lipid levels, blood pressure, and body mass index from childhood to adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. J Pediatr 2011; 159: 584–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herman KM, Craig CL, Gauvin L, Katzmarzyk PT. Tracking of obesity and physical activity from childhood to adulthood: the Physical Activity Longitudinal Study. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009; 4: 281–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Xu J, Berenson GS. Relation of childhood obesity/cardiometabolic phenotypes to adult cardiometabolic profile: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 176: S142–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjerregaard LG, Rasmussen KM, Michaelsen KF, et al. Effects of body size and change in body size from infancy through childhood on body mass index in adulthood. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014; 38: 1305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo SS, Wu W, Chumlea WC, Roche AF. Predicting overweight and obesity in adulthood from body mass index values in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 76: 653–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Bellisle F, Sempe M, Guilloud-Bataille M, Patois E. Adiposity rebound in children: a simple indicator for predicting obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 1984; 39: 129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekelund U, Ong K, Linne Y, et al. Upward weight percentile crossing in infancy and early childhood independently predicts fat mass in young adults: the Stockholm Weight Development Study (SWEDES). Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 83: 324–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stettler N, Kumanyika SK, Katz SH, Zemel BS, Stallings VA. Rapid weight gain during infancy and obesity in young adulthood in a cohort of African Americans. Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 77: 1374–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baird J, Fisher D, Lucas P, Kleijnen J, Roberts H, Law C. Being big or growing fast: systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. BMJ 2005; 331: 929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyer AR, Stamler J, Greenland P. Associations of weight change and weight variability with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the Chicago Western Electric Company Study. Am J Epidemiol 2000; 152: 324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folsom AR, French SA, Zheng W, Baxter JE, Jeffery RW. Weight variability and mortality: the Iowa Women's Health Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1996; 20: 704–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.French SA, Folsom AR, Jeffery RW, Zheng W, Mink PJ, Baxter JE. Weight variability and incident disease in older women: the Iowa Women's Health Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1997; 21: 217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lissner L, Odell PM, D'Agostino RB, et al. Variability of body weight and health outcomes in the Framingham population. N Engl J Med 1991; 324: 1839–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens J, Lissner L. Body weight variability and mortality in the Charleston Heart Study. Int J Obes 1990; 14: 385–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rzehak P, Meisinger C, Woelke G, Brasche S, Strube G, Heinrich J. Weight change, weight cycling and mortality in the ERFORT Male Cohort Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2007; 22: 665–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorpe KE, Yang Z, Long KM, Garvey WT. The impact of weight loss among seniors on Medicare spending. Health Econ Rev 2013; 3: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009; 374: 1677–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000. CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11 2002: 1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berenson GS, Wattigney WA, Bao W, Srinivasan SR, Radhakrishnamurthy B. Rationale to study the early natural history of heart disease: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Med Sci 1995; 310: S22–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster TA, Voors AW, Webber LS, Frerichs RR, Berenson GS. Anthropometric and maturation measurements of children, ages 5 to 14 years, in a biracial community–the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr 1977; 30: 582–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foster TA, Berenson GS. Measurement error and reliability in four pediatric cross-sectional surveys of cardiovascular disease risk factor variables–the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40: 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freedman DS, Blanck HM, Dietz WH, DasMahapatra P, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Is the body adiposity index (hip circumference/height(1.5)) more strongly related to skinfold thicknesses and risk factor levels than is BMI? The Bogalusa Heart Study. Br J Nutr 2013; 109: 338–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter SM, Webber LS, Berenson GS. Cigarette smoking and tobacco usage behavior in children with adolescents: Bogalusa Heart Study. Prev Med 1980; 9: 701–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li S, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, et al. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and carotid vascular changes in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. JAMA 2003; 290: 2271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen W, Li S, Cook NR, et al. An autosomal genome scan for loci influencing longitudinal burden of body mass index from childhood to young adulthood in white sibships: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004; 28: 462–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauer RM, Clarke WR, Beaglehole R. Level, trend, and variability of blood pressure during childhood: the Muscatine study. Circulation 1984; 69: 242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Field AE, Manson JE, Laird N, Williamson DF, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Weight cycling and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes among adult women in the United States. Obes Res 2004; 12: 267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimokoti RW, Newby PK, Gona P, et al. Diet quality, physical activity, smoking status, and weight fluctuation are associated with weight change in women and men. J Nutr 2010; 140: 1287–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lahti-Koski M, Mannisto S, Pietinen P, Vartiainen E. Prevalence of weight cycling and its relation to health indicators in Finland. Obes Res 2005; 13: 333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens VL, Jacobs EJ, Sun J, et al. Weight cycling and mortality in a large prospective US study. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 175: 785–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Speakman JR, Levitsky DA, Allison DB, et al. Set points, settling points and some alternative models: theoretical options to understand how genes and environments combine to regulate body adiposity. Dis Model Mech 2011; 4: 733–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor CB, Jatulis DE, Fortmann SP, Kraemer HC. Weight variability effects: a prospective analysis from the Stanford Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 141: 461–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.French SA, Jeffery RW, Folsom AR, Williamson DF, Byers T. Relation of weight variability and intentionality of weight loss to disease history and health-related variables in a population-based sample of women aged 55-69 years. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 142: 1306–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris RD, Rimm AA. Long-term weight fluctuation and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in white women. Ann Epidemiol 1992; 2: 657–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iribarren C, Sharp DS, Burchfiel CM, Petrovitch H. Association of weight loss and weight fluctuation with mortality among Japanese American men. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 686–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yatsuya H, Tamakoshi K, Yoshida T, et al. Association between weight fluctuation and fasting insulin concentration in Japanese men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27: 478–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang J, Loos RJ, Powell JE, et al. FTO genotype is associated with phenotypic variability of body mass index. Nature 2012; 490: 267–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sayers A, Heron J, Smith A, et al. Joint modelling compared with two stage methods for analysing longitudinal data and prospective outcomes: A simulation study of childhood growth and BP. Stat Methods Med Res 2014; 11: 0962280214548822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]