Abstract

Background

Marine fungi are a diverse group of opportunistic and obligate organisms isolated from marine environments. These fungi are now often included in screens for novel metabolites, while less attention has been given to their production of hydrolytic enzymes. Most enzymes derived from marine microorganisms have been obtained from marine bacteria. The enzymes produced by marine fungi may have different properties than those derived from bacteria or from terrestrial fungi. Here we assess the growth of six filamentous marine fungi on a wide range of polymeric substrates as an indication of their general capacity to produce hydrolytic enzymes.

Results

Calcarisporium sp. KF525, Tritirachium sp. LF562, Bartalinia robillardoides LF550, Penicillium pinophilum LF458, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis LF580 and Pestalotiopsis sp. KF079 all grew on both casein and gelatin as N-source, indicating secretion of proteases. All species also grew on starch, laminarin, xylan, pectin and oil, indicating production of amylases, glucanases, xylanases, pectinases and lipases. Growth on cellulose occurred but was weaker than on xylan. All strains also grew to some extent on sulphated arabinogalactan, although only LF562 could utilise arabinose. Four strains grew on the sulphated ulvans, whereas only KF525 grew on agar or carrageenan. KF525 and LF562 showed limited growth on alginate. Although fucose was used as carbon source by several species, fucoidan did not support biomass production.

Conclusions

Marine fungi could be excellent sources of a wide range of hydrolytic enzymes, including those able to hydrolyse various seaweed polymers. Although the native hosts may secrete only small amounts of these enzymes, the genes may provide a rich source of novel enzymes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12896-016-0233-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Marine fungi, Hydrolytic enzymes, Radial growth rate, Calcarisporium, Scopulariopsis, Tritirachium, Bartalinia, Penicillium, Pestalotiopsis

Background

Marine fungi are a diverse group of opportunistic and obligate organisms isolated from marine environments [1, 2]. In recent years interest in the secondary metabolites and bio-active compounds produced by some of these fungi has grown [2, 3] and they are increasingly included in ecological studies of marine environments [1, 2, 4]. Recent initiatives to develop and exploit marine resources have led to an increase in the isolation of these fungi and screening for novel compounds.

The marine environment provides microorganisms with substrates which may differ considerably from soil, freshwater and plant environments. For example, macroalgae (seaweeds) contain not only compounds like cellulose and xylan, but also a range of polysaccharides not generally observed in land organisms, such as alginate, agar, carrageenan, ulvan, and fucoidan, many of which are sulphated. The polymers may contain monomers of fucose and uronic acids. Although there are accounts of fungi able to degrade these polymers (e.g. [5–7]), most of the research has focused on bacterial enzymes [8]. Since fungi are well known for their ability to produce and secrete proteins, including industrially relevant enzymes, this may reflect a lack of access to marine fungal strains by those carrying out the majority of studies. Marine fungi which have been screened for enzymatic activies have generally been found to produce diverse activities [2].

Of the enzymes from marine fungi which have been studied, cellulases, xylanases and peroxidases have received the most interest [2]. Some of the enzymes identified have unique properties of cold [9], salt [10], alkali [11] or acid [12] tolerance, which may also be of commercial interest.

In this paper we consider the capacity of six diverse marine fungi (Calcarisporium sp., Tritirachium sp., Bartalinia robillardoides, Penicillium pinophilum, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis and Pestalotiopsis sp.) to utilise a range of polymeric substrates derived primarily from plants or macroalgae for growth (Additional file 1: Table S1). Growth on these substrates indicated that they produce a wide range of polymer degrading enzymes, including low levels of enzymes which degrade or modify sulphated polymers. The results confirm that marine fungi could be a good source of enzymes, including enzymes for degradation of macroalgal polymers, which may become more widely available as these are being considered as a source of biomass for biorefineries.

Results and discussion

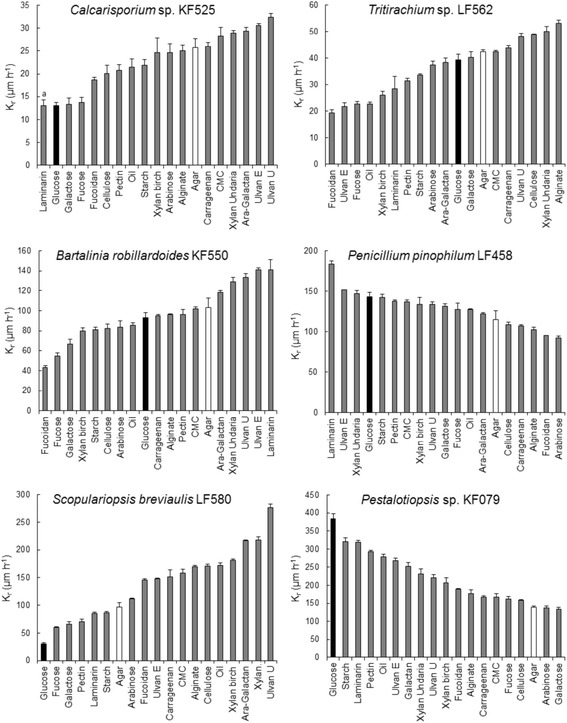

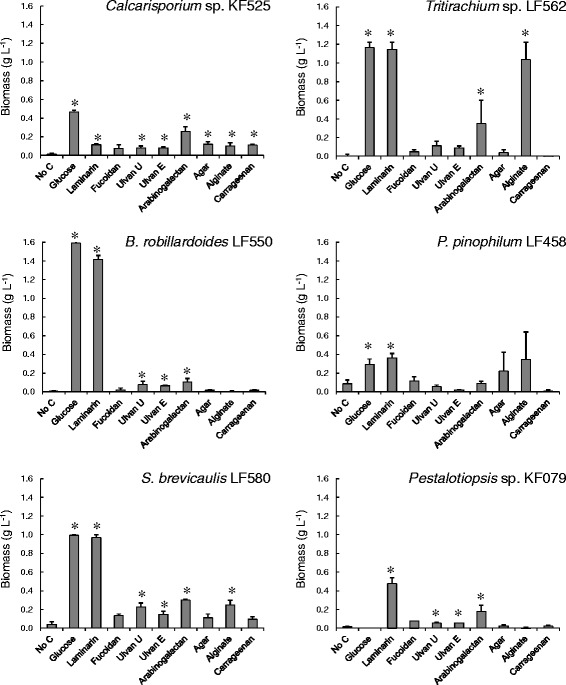

All strains grew with glucose as sole carbon source and nitrogen provided as ammonium (Table 1). To avoid the decrease in pH associated with uptake of ammonium from the medium, growth on urea was also assessed, but P. pinophilum LF458 was unable to use it as a nitrogen source and B. robillardoides LF550 grew poorly, so ammonium was used as the nitrogen source for comparing growth on the various carbon substrates. Growth was assessed as colony radial growth rate (Kr) on the various substrates (Fig. 1, Table 2) and as dry biomass on polymers derived from macroalgae (Fig. 2). It should be noted that colony radial growth rate does not necessarily reflect the amount of biomass produced [13]. Some strains branch less frequently on poor carbon sources, enabling the hyphae to extend more rapidly in search of better carbon sources. Thus growth (sparse or dense colonies) on agar-solidified medium was also assessed visually (Table 1). All strains grew to some extent on media containing only agar as carbon source or lacking nitrogen (Tables 1 and 2), which was taken into consideration when assessing growth on other substrates, such as arabinose.

Table 1.

Growth on agar-solidified medium with various carbon sources, ammonium as N source

| Straina | KF525 | LF562 | LF550 | LF458 | LF580 | KF079 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | ++++b | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Laminarin | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Starch | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Cellulose | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| CMC | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Xylan (birch) | +++ | ++++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Xylan (Undaria) | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Pectin | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Oil | +++ | +++ | ++++ | ++ | +++ | ++++ |

| Ulvan (Ulva) | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Ulvan (Enteromorpha) | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ |

| Arabinogalactan | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Galactose | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Arabinose | ++ | ++++ | + | + | + | ++ |

| Fucoidan | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Fucose | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Alginate | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Carrageenan | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Agar (no C) | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | ++ |

a Calcarisporium sp. KF525, Tritirachium sp. LF562, Bartalinia robillardoides LF550, P. pinophilum LF458, S. brevicaulis LF580 and Pestalotiopsis sp. KF079

bExtent of growth indicated as: + weak, ++ moderate, +++ good or ++++ very good

Fig. 1.

Colony radial growth rates (Kr) on various carbon sources, ammonium as N source. Fungi were grown on agar-solidified medium containing monomeric (glucose, galactose, arabinose or fucose) or polymeric carbon sources. The colony radial growth rate on glucose is indicated in black and on agar in white. Error bars represent ± sem. Xylan was derived from birch or U. pinnatifida. Ara-Galactan = sulphated arabinogalactan from C. fragile, Ulvan U = ulvan from U. armoricana and Ulvan E = ulvan from E. intestinalis

Table 2.

Kr and growth on agar-solidified medium with various N sources, glucose as C source

| Straing | KF525 | LF562 | LF550 | LF458 | LF580 | KF079 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium | 13 ± 1ea | 40 ± 2b | 93 ± 5b | 143 ± 5d | 30 ± 3a | 384 ± 15d |

| ++++f | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | |

| Nitrate | 16 ± 1b | 41 ± 1b | 60 ± 3a | 98 ± 2a | 134 ± 2c | 228 ± 4b |

| + | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | |

| Urea | 16 ± 2b | 40 ± 1b | 54 ± 2a | 110 ± 1ab | 103 ± 2b | 264 ± 3c |

| +++ | ++++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | |

| Casein | 21 ± 2b | 49 ± 0c | 94 ± 2b | 127 ± 2c | 198 ± 9d | 106 ± 2a |

| +++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | |

| Gelatin | 27 ± 1c | 49 ± 2c | 84 ± 4b | 115 ± 3b | 212 ± 3d | 236 ± 8bc |

| +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | |

| No nitrogen | 15 ± 1ab | 34 ± 1a | 63 ± 3a | 119 ± 1a | 99 ± 5b | 256 ± 7c |

| + | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ |

eValues are average Kr ± sem (μm h−1) for n = 4 to 12. Values for the same strain with the same superscript letter (a to d) did not differ significantly (p > 0.05)

fExtent of growth indicated as: + weak, ++ moderate, +++ good or ++++ very good

g Calcarisporium sp. KF525, Tritirachium sp. LF562, Bartalinia robillardoides LF550, P. pinophilum LF458, S. brevicaulis LF580 and Pestalotiopsis sp. KF079

Fig. 2.

Fungal biomass produced in liquid after 7 days from glucose or macroalgal carbon sources. Fungi were grown in flasks with 2 g L−1 of the substrate. Asterisks indicate values which differ significantly (p < 0.05) from the amount of biomass present in flasks which received no carbon source. Ulvan U = ulvan from U. armoricana and Ulvan E = ulvan from E. intestinalis

All strains grew on both casein and gelatin as nitrogen sources, indicating that all strains produced extracellular proteases (Table 2). Calcarisporium sp. KF525, Tritirachium sp. LF562, S. brevicaulis LF580, and Pestalotiopsis sp. KF079 caused precipitation of para-κ-casein from casein, whereas B. robillardoides LF550 and P. pinophilum LF458 did not. Growth on casein was generally better than growth on gelatin, but LF580 and LF562 grew equally on both protein sources. Good protease production has also been observed from marine derived Aspergillus, Beauveria and Acremonium species [14]. All strains except Calcarisporium sp. KF525 were able to use nitrate as sole nitrogen source (Table 2).

Growth of Calcarisporium sp. KF525 on polymeric carbon sources

Calcarisporium species are commonly isolated as mycoparasites or symbionts of higher fungi [15], and less frequently from marine environments. Strain KF525 was isolated from the German Wadden Sea and has been shown to produce macrocyclic and linear polyesters and cyclodepsipeptides [16, 17]. Parasitic species are also known to produce various bioactive compounds [18–21]. The variability of intracellular enzymes of some strains of C. arbuscula has been assessed [22]. The physiology of strain KF525 has not been extensively characterised, but Tamminen et al. [23] reported that it grew slowly (μ = 0.03 - 0.06 h–1) and did not grow at temperatures above 24 °C.

Calcarisporium sp. KF525 grew on agar-solidified medium on all carbon sources provided except perhaps arabinose, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and carrageenan, on which growth was similar to that observed on agar (Table 1, Fig. 1). It produced sparser, more rapidly extending hyphae in the absence of easily metabolised carbon source than in its presence (Fig. 1). Thus low Kr values for KF525 represent better growth than higher Kr values and glucose, laminarin, galactose and fucose represented the most readily utilised carbon sources (Kr ~ 13 μm h−1; Fig. 1, Table 1). Cellulose, pectin, oil, starch, and xylan (from either birch or from the macroalga Undaria pinnatifida) also supported good biomass production, although the Kr values were higher than on glucose. Growth on ulvans, fucoidan and alginate was more dense than that observed when agar was the only C-source or with agar and arabinose or carrageenan, although the Kr on ulvans was high (Fig. 1).

KF525 produced high background growth on medium containing only agar, suggesting that it was able to partially utilise agar as a carbon source. This was confirmed by growing KF525 in flasks in medium containing 2 g L−1 agar as the sole carbon source. Growth was observed within 7 days (0.12 ± 0.02 g l−1), whereas essentially no growth (0.01 ± 0.01 g L−1) had occurred in medium lacking a carbon source (Fig. 2). Similarly, KF525 grew on carrageenan (0.11 ± 0.01 g L−1), but did not completely metabolise it. Growth on ulvan (from either Ulva or Enteromorpha, 0.08 ± 0.01 g L−1), arabinogalactan (0.26 ± 0.05 g L−1), and alginate (OD or DW) in the absence of agar was also confirmed in liquid cultures. KF525 produced 0.47 ± 0.02 g l−1 biomass from glucose and 0.12 ± 0.01 g L−1 from laminarin during the same time interval.

KF525 showed the most extensive growth on substrates such as agar, carrageenan and alginates, of the fungi considered here. It also grew on sulphated ulvans and arabinogalactans, although it did not appear to utilise arabinose. The slow growth of KF525 would be undesirable in a production organism, but it may be a source of novel fungal enzymes which could be expressed in alternative hosts.

Growth of Tritirachium sp. LF562 on polymeric carbon sources

Tritirachium sp. LF562 was isolated from a sponge growing in the Adriatic Sea [24]. Tritirachium species have been described as airborne contaminants and have been isolated from plant and packing material [25] and from soil [26, 27]. T. album limber is a producer of serine protease [27, 28]. Although not common in the marine environment, T. candoliense has also been isolated from the anoxic zone in the Arabian Sea [29] and others have been isolated from Australian coastal waters [30]. Apart from the proteinases, hydrolytic enzymes have not been studied.

LF562 had a low Kr (19 to 53 μm h−1), changes in which did not reflect either good or poor growth (Fig. 1). Better growth was observed on galactose, fucose, arabinose, starch, laminarin, xylan (clearing zones present after 1 day of incubation), pectin and oil (Table 1). LF562 was the only strain included in this study which utilised arabinose as a carbon source. LF562 also grew on cellulose, and to some extent on CMC, ulvans, arabinogalactan, fucoidan, and alginate.

LF562 grew as well on laminarin as on glucose in liquid culture (Fig. 2), with a yield of 0.57 g biomass per g substrate consumed. Biomass production on arabinogalactan (0.35 ± 0.25 g L−1) and alginate (1.04 ± 0.19 g L−1) was also confirmed in liquid cultures. Biomass production from ulvans (0.12 ± 0.05 and 0.09 ± 0.02 g L−1) was comparable to that of KF525 or LF550, but was not significantly greater (p > 0.05) than that of the no carbon control because of variability between the cultures.

Growth of Bartalinia robillardoides LF550 on polymeric carbon sources

Bartalinia robillardoides LF550 was isolated from a marine sponge (Tethya aurantium) obtained from the Adriatic Sea near Rovinj, Croatia [24]. A Bartalinia specie has also been isolated from the sponge Gelliode fibrosa in the Pacific [31], but B. robillardoides strains are more typically isolated from plants [32, 33], leaf litter [34] or insect [32]. Apart from taxonomic studies, the main interest in B. robillardoides has been in its secondary metabolites, which include taxol [33] and various azophilones [35]. Enzyme activities from B. robillardoides have not been reported.

LF550 grew well on glucose, laminarin, starch, xylan (particularly that derived from the macroalga Undaria, clearing zones present after 1 day of incubation), pectin, oil, cellulose, CMC, galactose, and fucose (Table 1). Weak growth was observed on ulvans, arabinogalactan and fucoidan (Table 1). There was no clear correlation between Kr and good growth. Low Krs on fucoidan and fucose indicated that these substrates were perceived by the fungus. LF550 did not grow on arabinose and background growth on agar was very low. Growth on ulvans (0.08 ± 0.04 and 0.07 ± 0.01 g L−1) and arabinogalactan (0.11 ± 0.04 g L−1) was confirmed in liquid cultures, as was the inability to grow on agar (Fig. 2).

Growth of Penicillium pinophilum LF458 on polymeric carbon sources

Penicillium species, including P. pinophilum, are frequently isolated from marine environments [24, 30, 36], as well as being common in soil and other land environments. P. pinophilum, like other penicillia, is known for producing bioactive metabolites [36, 37]. Enzymes involved in the degradation of lignocellulosic biomass have been identified from various isolates [38–42], and a gene encoding a dextranase was recently cloned from a marine isolate [43].

Like KF079, LF458 generally showed reduced rates of expansion on poor carbon sources, although Kr was not strongly affected by the carbon source (Fig. 1). Dense growth was observed on galactose, starch, laminarin, xylan (clearing zones present after 1 day of incubation), and pectin (Table 1). Weak growth was observed on cellulose, CMC, oil, ulvans, arabinogalactan, fucose, fucoidan, alginate and carrageenan. Background growth on agar was very low, as was growth on arabinose. Utilisation of ulvans, fucoidan, alginate, agar or carrageenan was not observed in liquid culture, in which LF458 grew poorly as pellets, with high variation between cultures (Fig. 2). Even in glucose (0.29 ± 0.06 g L−1) and laminarin (0.36 ± 0.05 g L−1) containing medium, biomass production was low even though all glucose had been consumed.

Growth of Scopulariopsis brevicaulis LF580 on polymeric carbon sources

Scopulariopsis brevicaulis is the anamorph of Microascus brevicaulis and is commonly found in soil environments. Some strains have been isolated from skin or nails, where it appears to be an opportunistic pathogen. It has only occasionally been isolated from marine environments [44–46], but has also been found in other high salt environments [47, 48]. Production of keratinase [49] and L-methioninase [50] has been reported.

Like KF525, LF580 produced sparser, more rapidly extending hyphae in the absence of easily metabolised carbon source than on glucose (Fig. 1). However, colonies produced on glucose were much more compact (low Kr) than those growing on fucose, galactose, pectin, laminarin, starch or xylan (clearing zones present after 1 day of incubation), although these substrates also supported good biomass production (Table 1). Thus high Kr values for LF580 do not necessarily represent poor growth. Colony expansion on glucose may have been affected by reduction in the local pH (pH ~4 at the edge of colonies grown on glucose with ammonium, while remaining close to 5.5 at the edge of the plate), caused by ammonium uptake in the poorly buffered medium. This hypothesis was supported by the much higher colony expansion rates observed on medium containing either urea (pH ~5 at edge of colony) or nitrate (pH ~8 at colony edge) (Table 2). However, this reduction in pH did not appear to affect growth in liquid medium, in which glucose was completely metabolised (Fig. 2). LF580 also grew on oil, cellulose, CMC and arabinogalactan, whereas growth on carrageenan, alginate or fucose was poor, with even less growth on arabinose, ulvans, fucoidan or agar (Table 1). LF580 colonies expanded much more rapidly on these carbon sources than on agar, indicating that they were sensed by the fungus.

The genome of S. brevicaulis LF580 was recently published and the profile of putative carbohydrate-active enzymes identified in the genome analysis [51]. Kumar et al. [51] concluded that LF580 should be well adapted for the breakdown of terrestrial plant materials, having numerous putative glycoside hydrolases with homology to xylanases, pectinases, cellulases and lytic polysaccharide mono-oxygenases. The good growth on xylan and pectin supported their conclusions, although growth on cellulose was weaker than might have been expected.

LF580 produced less background growth on agar-solidified medium lacking other carbon source than KF525 or LF562. Growth in flasks containing 2 g L−1 agar as the sole carbon source was not significantly greater (p > 0.05) than in flasks without carbon source (Fig. 2). However, measureable growth (p < 0.05) was observed on alginate (0.25 ± 0.05 g L−1) and arabinogalactan (0.3 ± 0.01 g L−1). More biomass was produced from ulvans (0.15 ± 0.04 and 0.23 ± 0.04 g L−1) than was expected based on the growth on agar-solidified medium. Biomass production from laminarin (0.97 ± 0.03 g L−1) was similar to that from glucose (1.00 ± 0.01 g L−1), with a yield of 0.49 g biomass per g substrate indicating complete metabolism (Fig. 2). However, as predicted [51], LF580 appears better adapted for hydrolysis of plant than of macroalgal biomass.

Growth of Pestalotiopsis sp. KF079 on polymeric carbon sources

Pestalotiopsis species are predominantly anamorphic, commonly found as endophytes or plant pathogens, but also able to live saprophytically, and are isolated from very diverse environments, including marine environments [52, 53]. They have recently gained considerable interest because of the diversity of secondary metabolites of potential commercial interest which they produce [53]. The cellulases, hemicellulases and laccases of some strains isolated from mangrove swamps have also been investigated [54, 55].

KF079 had a high Kr on glucose (384 ± 19 μm h−1) and generally showed reduced rates of expansion on poor carbon sources (Fig. 1). Dense growth at high Kr values was observed on starch, laminarin, pectin and oil, while dense growth with lower colony expansion rates was observed on xylan (clearing zones present after 1 day of incubation), cellulose, CMC and galactose (Fig. 1). Weak growth was observed on ulvans, arabinogalactan, fucoidan, fucose, arabinose, alginate and carrageenan (Table 1). Background growth on agar was relatively high, but measurable biomass production was not observed within 7 days in shaken flasks containing 2 g l−1 agar (0.03 ± 0.01 g l−1, compared to 0.02 ± 0.01 g l−1 without added carbon, Fig. 2). No biomass was produced from alginate or carrageenan in liquid culture, but growth of KF079 on ulvans (either from Ulva or Enteromorpha, 0.05 ± 0.00 g l−1), fucoidan (0.08 g l−1) and arabinogalactan (0.18 ± 0.07 g l−1) was observed. Laminarin (0.48 ± 0.06 g l−1) was used as the control. KF079 thus appeared more likely to be a source of enzymes for hydrolysing plant biomass than for seaweed-derived biomass, although its ability to utilise ulvans may be of interest.

Conclusions

Growth of Calcarisporium sp. KF525, Tritirachium sp. LF562, Bartalinia robillardoides LF550, Penicillium pinophilum LF458, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis LF580 and Pestalotiopsis sp. KF079 on polymeric substrates demonstrated that each was able to produce protease, amylase, glucanase, xylanase, pectinases and lipase. Growth on laminarin and starch was generally comparable to that on glucose, demonstrating the efficiency with which amylases and glucanases were produced. Although they grew well on xylan, none of these cells grew well on cellulose or CMC, indicating only weak production of cellulase or endoglucanase.

All strains except P. pinophilum LF458 were also able to grow on sulphated arabinogalactan, even though only Tritirachium sp. LF562 could metabolise arabinose. All strains utilised galactose. Only Calcarisporium sp. KF525 produced biomass from the sulphated galactans, agar and carrageenan. Agarases and carageenases from bacteria have received considerable attention [8], but there are few reports of these activities from filamentous fungi [5].

The sulphated fucoidan was not clearly metabolised by any strain, although they appeared able to use fucose as a carbon source and all responded to the presence of fucoidan in the medium.

Several strains grew on both sources of ulvan, indicating that they may be a source for novel ulvan and glucuronan lyases or hydrolases, few of which have been characterised [56–59]. However, the limited growth observed on ulvan suggests that the enzyme levels are low, or that these strains do not have complete pathways for its degradation.

Calcarisporium sp. KF525, S. brevicaulis LF580 and Tritirachium sp. LF562 produced biomass from alginate. Although most studies of alginate lyases have focused on those obtained from marine bacteria [8], alginate lyase activity has also been observed in marine isolates of A. oryzae [6] and Dendryphiella salina [7].

Marine fungi clearly produce a wide range of hydrolytic activities and should be considered as more than just providers of novel lignocellulolytic enzymes. More in depth study of the enzymes from marine fungi, as well as from bacteria, is needed to identify novel activities and enzymes with novel properties to enhance our understanding of polymer metabolism and to provide catalysts for future biorefineries. Although the native hosts may secrete only small amounts of these enzymes, their genes may provide a rich new source of novel enzymes.

Methods

Strains

Calcarisporium sp. KF525, Tritirachium sp. LF562, Bartalinia robillardoides LF550, Penicillium pinophilum LF458, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis LF580 and Pestalotiopsis sp. KF079 were obtained from the culture collection of the Kiel Center for marine natural products at GEOMAR, Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, as a kind gift from A. Labes and J. F. Imhoff. Stock cultures were maintained as conidia or mycelial fragments suspended in 20 % v/v glycerol, 0.8 % w/v NaCl with ~0.025 % v/v Tween 20 or on Microbank™ Bacterial and Fungal Preservation System beads (Pro-Lab Diagnostics, UK) at −80 °C. Spores of Calcarisporium sp. KF525 were obtained from cultures growing in shaken flasks on Yeast Malt Peptone (YMP, 3 g L−1 yeast extract, 3 g L−1 malt extract, 5 g L−1 peptone) medium containing 30 g L−1 Sea Salt (Tropic Marin®, Germany) for 11 days, after removal of the mycelia by filtration through cotton. Spores of Penicillium pinophilum LF458 and Scopulariopsis brevicaulis LF580 were obtained from cultures growing on agar-solidified (15 g L−1 agar) YMP medium containing 30 g Tropic Marin® Sea Salt L−1. Tritirachium sp. LF562, Bartalinia robillardoides LF550 and Pestalotiopsis sp. KF079 sporulated poorly.

Media

The defined medium (initial pH ~5.5) contained 0.5 g L−1 KH2PO4, 0.1 g L−1 MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.05 g L−1 CaCl2 · 2H2O, 5 mg L−1 Citric acid · H2O, 5 mg L−1 ZnSO4 · 7H2O, 1 mg L−1 Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 · 6H2O, 50 μg L−1 MnSO4 · 4H2O, 260 μg L−1 CuSO4 · 5H2O, 50 μg L−1 H3BO3, 50 μg L−1 Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, and 50 μg L−1 biotin. Ammonium sulphate (3.3 g L−1), sodium nitrate (4.25 g L−1), urea (1.5 g L−1), casein (4 g L−1) or gelatin (4 g L−1) were provided as nitrogen source. Glucose (2 or 10 g L−1), fucose, galactose, arabinose, starch, pectin from citrus, cellulose, carboxy-methyl cellulose (CMC), laminarin (from Laminaria digitata, Sigma-Aldrich), xylan (from birch, Sigma-Aldrich, or from Undaria pinnatifida, Elicityl SA), ulvan (from Ulva armoricana or Enteromorpha intestinalis, Elicityl SA), sulphated arabinogalactan (from Codium fragile, Elicityl SA), carrageenan (from Eucheuma cottonii, Sigma-Aldrich), agar (noble, Difco), sodium alginate (from Macrocystis pyrifera, Sigma-Aldrich), or fucoidan (from Fucus vesiculosus, Sigma-Aldrich) (10 g L-1 except for polymers derived from macroalgae, which were 2 g L−1) were provided as primary carbon sources. Carbon sources, casein and gelatin were sterilised by autoclaving in water or water containing agar (pH 7) at 121 °C for 15 to 20 min. Salts and inorganic N-sources were sterilised by filtration and added as a concentrated solution to the sterile carbon sources. Agar solidified media contained 15 g L−1 agar. All media contained 30 g Tropic Marin® Sea Salt L−1 (prepared as a 3-fold concentrated stock, sterilised by filtration). The composition (monomers and their linkage) of polymeric substrates is described in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Cultural conditions and measurements of growth

Flasks (50 or 100 mL, containing 10 mL medium) were inoculated with conidial suspensions or with approximately 2 x 2 mm2 pieces of mycelium, excised from YMP medium and from which excess agar had been removed, and incubated at 22 °C (Calcarisporium sp. KF525) or 30 °C (all other strains), 180 rpm.

Agar-solidified medium (in 4.5 or 9 cm diameter Petri dishes) was inoculated centrally with 2 μl spore suspension or with approximately 2 x 2 mm2 pieces of mycelium, excised from YMP medium and from which excess agar had been removed. Petri dishes were incubated inverted at 22 °C (KF525) or 30 °C (all other strains).

Colony radial expansion rates (Kr) were calculated from measurements of colony diameter at 24 to 48 h intervals. Biomass from liquid cultures was collected by filtration (Millipore 0.22 μm GSWP filters or Whatman filter paper 1), washed twice with excess water and taken to dryness at 65 °C. To remove agar, alginate and carrageenan, the culture was warmed at 100 °C then washed twice in excess hot (100 °C) water, which was removed by centrifugation, before collecting the biomass by filtration. This heat treatment may cause some cell lysis and result in an underestimate of the fungal biomass, but was preferable to overestimating the biomass by failing to remove the polymers, which could lead to false conclusions about consumption of the polymer.

The presence or absence of glucose in flask cultures was assessed using Roche Keto-Diabur-Test 5000 sticks, which show green colour changes in the presence of low concentrations (<1 g L−1) of glucose. The pH of agar at the edge of colonies was estimated using Merck Acilit® (pH 0–6) or Alkalit® (pH 7.5–14) pH indicator sticks.

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Labes and J. F. Imhoff from the Kiel Center for marine natural products at GEOMAR, Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel for the fungal isolates and for stimulating conversations about marine fungi. We thank Jenni Heikkinen, Merja Aarnio, and Birgit Hillebrandt-Chellaoui for valuable assistance in the lab. We thank the European Union for the 7th Framework KBBE project MARINE FUNGI (project no. 265926) and the Academy of Finland for grant 289055 (MarineCarb).

Additional file

Characteristics of polymeric substrates used in this study. (DOCX 22 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

This study was conceived by MGW. MGW, YW and AT carried out experimental work. MGW, DB, YW and AT contributed to the writing and review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yanming Wang, Email: yanming.wang@vtt.fi.

Dorothee Barth, Email: dorothee.barth@vtt.fi.

Anu Tamminen, Email: anu.tamminen@vtt.fi.

Marilyn G. Wiebe, Email: marilyn.wiebe@vtt.fi

References

- 1.Raghukumar C. Marine fungal biotechnology: an ecological perspective. Fungal Divers. 2008;31:19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones EBG. Fifty years of marine mycology. Fungal Divers. 2011;50:73–112. doi: 10.1007/s13225-011-0119-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhadury P, Mohammad BT, Wright PC. The current status of natural products from marine fungi and their potential as anti-infective agents. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;33:325–337. doi: 10.1007/s10295-005-0070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velmurugan S, Prasannakumar C, Manokaran S, Ajith Kumar T, Samkamaleson A, Palavesam A. DNA barcodes for marine fungal identification and discovery. Fungal Ecol. 2013;6:408–418. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2013.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solis MJL, Draeger S, dela Cruz TEE. Marine-derived fungi from Kappaphycus alvarezii and K. striatum as potential causative agents of ice-ice disease in farmed seaweeds. Bot Mar. 2010;53:587–594. doi: 10.1515/bot.2010.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh RP, Gupta V, Kumari P, Kumar M, Reddy CRK, Prasad K, Jha B. Purification and partial characterization of an extracellular alginate lyase from Aspergillus oryzae isolated from brown seaweed. J Appl Phycol. 2011;23:755–762. doi: 10.1007/s10811-010-9576-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moen E, Alvarez-Colsa P, Larsen BA, Ostgaard K. Degradation of alginate by the marine fungus Dendryphiella salina. J Mar Biotechnol. 1995;3:140–142. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin M, Portetelle D, Michel G, Vandenbol M. Microorganisms living on macroalgae: diversity, interactions, and biotechnological applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:2917–2935. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5557-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del-Cid A, Ubilla P, Ravanal MC, Medina E, Vaca I, Levicán G, Eyzaguirre J, Chávez R. Cold-active xylanase produced by fungi associated with Antarctic marine sponges. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;172:524–532. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panno L, Bruno M, Voyron S, Anastasi A, Gnavi G, Miserere L, Varese GC. Diversity, ecological role and potential biotechnological applications of marine fungi associated to the seagrass Posidonia oceanica. N Biotechnol. 2013;30:686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravindran C, Naveenan T, Varatharajan GR. Optimization of alkaline cellulase production by the marine-derived fungus Chaetomium sp. using agricultural and industrial wastes as substrates. Bot Mar. 2010;53:275–282. doi: 10.1515/BOT.2010.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beena PS, Soorej MB, Elyas KK, Bhat Sarita G, Chandrasekaran M. Acidophilic tannase from marine Aspergillus awamori BTMFW032. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;20:1403–1414. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1004.04038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bull AT, Trinci APJ. The physiology and metabolic control of fungal growth. In: Rose AH, Tempest DW, editors. Advances in Microbial Physiology. New York: Academic; 1977. pp. 1–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamat T, Rodrigues C, Naik CG. Marine-derived fungi as a source of proteases. Indian J Mar Sci. 2008;37:326–328. [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Hoog G. The genera Blastobotrys, Sporothrix, Calcarisporium and Calcarisporiells gen. nov. Stud Mycol. 1974;7:1–84. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silber J, Ohlendorf B, Labes A, Näther C, Imhoff JF. Calcaripeptides A-C, cyclodepsipeptides from a Calcarisporium strain. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:1461–1467. doi: 10.1021/np400262t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silber J, Ohlendorf B, Labes A, Erhard A, Imhoff JF. Calcarides A-E, antibacterial macrocyclic and linear polyesters from a Calcarisporium strain. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:3309–3323. doi: 10.3390/md11093309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu N-J, Guo S-X, Xiao P-G. New sesquiterpene esters from the culture filtrate of Calcarisporium arbuscula isolated from Ganoderma lucidum. Acta Bot Sin. 2002;44:878–882. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu N-J, Guo S-X, Lu H-Y. Cytotoxic macrocyclic trichothecenes from the mycelia of Calcarisporium arbuscula Preuss. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2002;4:179–183. doi: 10.1080/10286020290011387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulheirn LJ, Beechey RB, Leworthy DP, Osselton MD. Aurovertin B, a metabolite of Calcarisporium arbuscula. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1974;1974:874–876. doi: 10.1039/c39740000874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chrisp P, Dewick PM, Boyle FT. Antifungal antibiotics from Calcarisporium thermophilum: a new source of 15-azahomosterol derivatives. Z Naturforsch C. 2015;45:179–186. doi: 10.1515/znc-1990-3-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacharme J, Seigle-Murandi F, Tardieu F. Isoenzymes chez deux especes de micromycetes: aspect taxonomique. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1982;176:335–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamminen A, Wang Y, Wiebe M. Production of Calcaride A by Calcarisporium sp. in Shaken Flasks and Stirred Bioreactors. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:3992–4005. doi: 10.3390/md13073992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiese J, Ohlendorf B, Blümel M, Schmaljohann R, Imhoff JF. Phylogenetic identification of fungi isolated from the marine sponge Tethya aurantium and identification of their secondary metabolites. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:561–85. doi: 10.3390/md9040561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Hoog GS. The genera Beauveria, Isaria, Tritirachium and Acrodontium gen. Stud Mycol. 1972;1:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pakshir K, Ghiasi MR, Zomorodian K, Gharavi AR. Isolation and Molecular Identification of Keratinophilic Fungi from Public Parks Soil in Shiraz. Iran Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:619576. doi: 10.1155/2013/619576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebeling W, Hennrich N, Klockow M, Metz H, Orth HD, Lang H. Proteinase K from Tritirachium album Limber. Eur J Biochem. 1974;47:91–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samal BB, Karan B, Boone TC, Osslund TD, Chen KK, Stabinsky Y. Isolation and characterization of the gene encoding a novel, thermostable serine proteinase from the mould Tritirachium album Limber. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1789–1792. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manohar CS, Boekhout T, Müller WH, Stoeck T. Tritirachium candoliense sp. nov., a novel basidiomycetous fungus isolated from the anoxic zone of the Arabian Sea. Fungal Biol. 2014;118:139–49. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andreakis N, Høj L, Kearns P, Hall MR, Ericson G, Cobb RE, Gordon BR, Evans-Illidge E. Diversity of marine-derived fungal cultures exposed by DNA barcodes: The algorithm matters. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0136130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Q, Wang G. Diversity of fungal isolates from three Hawaiian marine sponges. Microbiol Res. 2009;164:233–41. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crous PW, Giraldo A, Hawksworth DL, Robert V, Kirk PM, Guarro J, Schoch CL, Damm U, Trakunyingcharoen T, Groenewald JZ. The Genera of Fungi : fixing the application of type species of generic names. IMA Fungus. 2014;5:141–160. doi: 10.5598/imafungus.2014.05.01.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gangadevi V, Muthumary J. Taxol, an anticancer drug produced by an endophytic fungus Bartalinia robillardoides Tassi, isolated from a medicinal plant, Aegle marmelos Correa ex Roxb. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;24:717–724. doi: 10.1007/s11274-007-9530-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shanthi S, Vittal B. Biodiversity of microfungi associated with litter of Pavetta indica. Mycosphere. 2010;1:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jansen N, Ohlendorf B, Erhard A, Bruhn T, Bringmann G, Imhoff JF. Helicusin E, isochromophilone X and isochromophilone XI: new chloroazaphilones produced by the fungus Bartalinia robillardoides strain LF550. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:800–16. doi: 10.3390/md11030800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao D-L, Shao C-L, Zhang Q, Wang K-L, Guan F-F, Shi T, Wang C-Y. Azaphilone and diphenyl ether derivatives from a Gorgonian-derived strain of the fungus Penicillium pinophilum. J Nat Prod. 2015;78:2310–4. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang M-H, Li X-M, Li C-S, Ji N-Y, Wang B-G. Secondary metabolites from Penicillium pinophilum SD-272, a marine sediment-derived fungus. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:2230–8. doi: 10.3390/md11062230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhakar K, Jain R, Tamta S, Pandey A. Prolonged laccase production by a cold and pH tolerant strain of Penicillium pinophilum (MCC 1049) isolated from a low temperature environment. Enzyme Res. 2014;2014:120708. doi: 10.1155/2014/120708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panagiotidou E, Konidaris C, Baklavaridis A, Zuburtikudis I, Achilias D, Mitlianga P. A simple route for purifying extracellular poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) - depolymerase from Penicillium pinophilum. Enzyme Res. 2014;2014(i):6. doi: 10.1155/2014/159809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai H, Shi P, Luo H, Bai Y, Huang H, Yang P, Yao B. Acidic β-mannanase from Penicillium pinophilum C1: Cloning, characterization and assessment of its potential for animal feed application. J Biosci Bioeng. 2011;112:551–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai H, Shi P, Bai Y, Huang H, Yuan T, Yang P, Luo H, Meng K, Yao B. A novel thermoacidophilic family 10 xylanase from Penicillium pinophilum C1. Process Biochem. 2011;46:2341–2346. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2011.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joo A-R, Jeya M, Lee K-M, Lee K-M, Moon H-J, Kim Y-S, Lee J-K. Production and characterization of β-1,4-glucosidase from a strain of Penicillium pinophilum. Process Biochem. 2010;45:851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2010.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rerngsamran P, Temjitpukdee P, Assavasirijinda N, Chareonpornwattana S. Cloning, characterization, and heterologous expression of a dextranase gene from Penicillium pinophilum SMCU3. Sci-J Sci Soc Thail. 2014;40:405–413. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding B, Yin Y, Zhang F, Li Z. Recovery and Phylogenetic Diversity of Culturable Fungi Associated with Marine Sponges Clathrina luteoculcitella and Holoxea sp. in the South China Sea. Mar Biotechnol. 2011;13:713–721. doi: 10.1007/s10126-010-9333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Ker C, Petit KE, Biard JF, Fleurence J. Search for hydrophilic marine fungal metabolites: A rational approach for their production and extraction in a bioactivity screening context. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:82–97. doi: 10.3390/md9010082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu Z, Lang G, Kajahn I, Schmaljohann R, Imhoff JF. Scopularides A and B, cyclodepsipeptides from a marine sponge-derived fungus, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1052–1054. doi: 10.1021/np070580e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mudau MM, Setati ME. Screening and identification of endomannanase-producing microfungi from hypersaline environments. Curr Microbiol. 2006;52:477–481. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0439-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoder JA, Benoit JB, Zettler LW. Effects of salt and temperature on the growth rate of a tick-associated fungus, Scopulariopsis brevicaulis Bainier (Deuteromycota) Int J Acarol. 2003;29:265–269. doi: 10.1080/01647950308684338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anbu P, Gopinath SCB, Hilda A, Lakshmipriya T, Annadurai G. Optimization of extracellular keratinase production by poultry farm isolate Scopulariopsis brevicaulis. Bioresour Technol. 2007;98:1298–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khalaf SA, El-Sayed AS. L-Methioninase production by filamentous fungi: I-screening and optimization under submerged conditions. Curr Microbiol. 2009;58:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar A, Henrissat B, Arvas M, Syed MF, Thieme N, Benz JP, Sørensen JL, Record E, Pöggeler S, Kempken F. De novo assembly and genome analyses of the marine-derived Scopulariopsis brevicaulis strain LF580 unravels life-style traits and anticancerous scopularide biosynthetic gene cluster. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0140398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maharachchikumbura SSN, Hyde KD, Groenewald JZ, Xu J, Crous PW. Pestalotiopsis revisited. Stud Mycol. 2014;79:121–186. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu J, Yang X, Lin Q. Chemistry and biology of Pestalotiopsis-derived natural products. Fungal Divers. 2014;66:37–68. doi: 10.1007/s13225-014-0288-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arfi Y, Chevret D, Henrissat B, Berrin J-G, Levasseur A, Record E. Characterization of salt-adapted secreted lignocellulolytic enzymes from the mangrove fungus Pestalotiopsis sp. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1810. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen H-Y, Xue D-S, Feng X-Y, Yao S-J. Screening and Production of Ligninolytic Enzyme by a Marine-Derived Fungal Pestalotiopsis sp. J63. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;165:1754–1769. doi: 10.1007/s12010-011-9392-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nyvall Collen P, Sassi J-F, Rogniaux H, Marfaing H, Helbert W. Ulvan lyases isolated from the flavobacteria Persicivirga ulvanivorans are the first members of a new polysaccharide lyase family. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42063–42071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.271825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collén PN, Jeudy A, Sassi J-F, Groisillier A, Czjzek M, Coutinho PM, Helbert W. A novel unsaturated β-glucuronyl hydrolase involved in ulvan degradation unveils the versatility of stereochemistry requirements in family GH105. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:6199–6211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.537480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Delattre C, Michaud P, Keller C, Elboutachfaiti R, Beven L, Courtois B, Courtois J. Purification and characterization of a novel glucuronan lyase from Trichoderma sp. GL2. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;70:437–443. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coste O, Malta E, López JC, Fernández-Díaz C. Production of sulfated oligosaccharides from the seaweed Ulva sp. using a new ulvan-degrading enzymatic bacterial crude extract. Algal Res. 2015;10:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2015.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]