Abstract

Background: Health inequality monitoring especially in Health care financing field is very important. Hence, this study tends to assess the inequality in household's capacity to pay and out-of-pocket health carepaymentsin Tehran metropolis.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was performed in 2013.Thestudy population was selected by stratified cluster sampling, and they constitute the typical households living in Tehran (2200 households). The required data were collected through questionnaires and analyzed using Excel and Stata v.11. Concentration Index on inequality was used for measuring inequality status in capacity to pay and household payments for health care expenses; and also the concentration index for out-of-pocket payments and capacity to pay was used to determine the extent of inequality. The recall period for inpatient care was one year and 1 month for outpatient.

Results: The average of out-of-pocket payments for receiving the outpatient services was determined to be 44.33US$ and for each inpatient1861.11 US$. Concentration index for household's outof- pocket payments for inpatient health care, out-of-pocket payments for outpatient health care and health prepayments were calculated 0.13, -0.10 and -0.11, respectively. Also, concentration index in household’s capacity to pay was estimated to be 0.11whichindicatedinequality to the benefit of the rich. The households used financing strategies like savings, borrowing or lending to pay their health care expenditures.

Conclusion: According to this study, the poor spend a greater portion of their capacity to pay for outpatient and inpatient health care costs and prepayment, in comparison to the rich. Thus, supporting the vulnerable groups of the society to decrease out-of-pocket payments and increasing the household’s capacity to pay through government support in order to improve the household economic potential, must be considered very important.

Keywords: Health inequality, Healthcare financing, Out-of-pocket payment, Capacity to pay

Introduction

Equality is one of the most frequent words in the social literature of almost all nations. Scholars in social field and governments during history have not been oblivious to this concept and even in spite of conflicts; they have tried to be advocates of equality (1). The right to have access to healthcare and medical services is granted in many societies providing the equal opportunities for all individuals in community. To this goal, financing, accessibility and utilization are the prerequisites. In this regard social equality has the main role. Annual monitoring of equality indices in health, especially in the field of health financing, is very useful and essential to provide an appropriate perspective in policy making (2).

The World Health Organization (WHO) in 2000 stated that one of the three objectives of the health systems is fair participation to finance the health (3).However, nowadays, many factors have increased the health care costs including expensive health care technologies (4), and improving knowledge and people's health expectations (5). Another impacting factor is inflation which is very prominent in the health sector (6). Increase in health and medical costs will cause many problems. For instance, households, especially the vulnerable group, will face many difficulties due to the health care financing; they will reduce other expenses in other parts of their lives that will decline households’ welfare (4). The heavy cost of health care services is called “catastrophic expenditure” (7). Catastrophic expenditures occur when the health care costs are more than 40% of the household's capacity to pay;(residual household income after basic needs is known as the "ability to pay".) (7,8). The financial burden of health costs due to the reduction in savings and less allocating of the household’s income to other expenses like as suitable food or appropriate training and education has an undeniable effect especially on children, and households’ product ability. Therefore the negative impact of poor performance of health care financing system can obviously be observed in capital accumulation and consequently production, economic growth and development in future (9). It is possible for a group of households give up the treatment, due to the inability to pay for treatment, and this will lead to decrease in the level of health care in households and society. All over the world, household, spend part of their income for health care costs. The amount of this part and its distribution in society (its equivalence) represents the imposition of financial burden of health on societies (5). Iran's health system, such as many other developing countries, is based on public and private sector cooperation. The active insuring organizations in Iran are including Medical Care Insurance Organization (MCIO) (covering 50.6% of the insured), Social Security Organization (SSO) (36.8% of the insured), Armed Forces Medical Care Insurance Organization (6.1%), Imam Khomeini Relief Committee (IKRC) (3.8%), Martyr Foundation and the Veterans Affairs (0.4%), Oil (0.9%) and other organizations (1.3%) (10,11).

In Iran, in recent years, supporting the households against health costs and providing access to health care services needed by the citizens are considered as critical issues. The 90th Article of the Fourth Development Plan reads that: “for providing the fair access to health services and reducing the share of vulnerable and low-income households for paying the costs, the facilities and distribution of resources must be in the way that fairness in financial contribution index (FFC) increases to 0.90 and out-of-pocket payments should not exceed o f30 percent, and the number of vulnerable households from intolerable health costs should decreased to 1percent. The Ministry of Health and Medical Education, in collaboration with Management and Planning Organization must present the bylaw of people’s balanced participation in providing healthcare resources for achieving the mentioned goals six months after notification. The bylaw would be confirmed by the Council of Ministers (12).

Studies conducted in Iran reflect the dire situation of equality in healthcare financing in households. Also every year, at least 2% of people will be in poverty due to the catastrophic health expenditure (13). The aforementioned evidence makes clear the necessity of conducting follow-up studies in the country (14). Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate inequality in household’s capacity to pay and out-of-pocket payments for health care in Tehran metropolis.

Methods

This is descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study performed in Tehran, 2013. The typical households, who reside in Tehran at least between 2012 and 2013, constituted the study population. In this study we used cluster sampling method and the samples are urban typical households who have resided in Tehran at least one year before the data collection. In this study 2200 households were selected. Tehran metropolis has 22 regions. In this study a quota sampling was used, therefore close to 100 questionnaires were considered for each region. Each region composed of several district, and every district consisted of several neighborhoods. Therefore, using cluster sampling one district from each region and one neighborhood from each district was selected randomly. Block sampling consisted of three steps: 1. To determine the sampling characteristics, 2. Collecting the samples, and 3. Completing the questionnaires. Sampling characteristics included determining the start point in each block, determining the distance number and studied households.

In this study, data collection was performed through questionnaires. The opinions of experts in health economic were used to confirm superficial validity of the questionnaire. For evaluating the content validity we checked many other existing questionnaires including the World Health Survey Questionnaire which was written according to the evaluation of system function (15); the questionnaire of household budget by Statistical Center of Iran (16), and international studies related to justice in health care financing and access and having health services (15,17,36).

The first part of our questionnaire includes the socio-economic data of the households. The second part is related to food and non-food non-health costs and also health prepayments. The third part is related to the household income. Since some households refrained to answer the income questions or provided unreal data, households gross expenditure with assuming lack of (zero) savings was considered as their income; this method is also has being used in many other studies (37-39). In the fourth part, there were two questions about whether households have disabled individuals or patients who needs long-term health care. The fifth part of the questionnaire is related to the family members’ demographic characteristics, including the age, gender, height, weight, assess the oral health status, health behavior status, marriage status, the type of insurance, work status, etc. Part Six was about the times they need inpatient and outpatient health care, based on their statements. Part seven was about the access status, using the outpatient care and the direct and indirect costs for type of service and the places they go for health care for every member of the household. And the part eight was about the access status and using the inpatient care for type of service and the places they go for health care for every member of the household. The recall period for outpatient patients in this study was one month and for inpatient patients one year.

The data were collected through interviewing with householder or individuals over 18 years who were knowledgeable on the required data. In some cases the required data were collected through observing documents. The gathered data were recorded in the questionnaires by interviewers. If a specific household was living less than one year in Tehran, it was excluded and replaced with another household from the right side. In case there was no one at home at the first presence, then after 5 days the interviewer referred back to that household again; and for unavailability of the household for the second time, the household was replaced with another household from the right side.

Concentration curve was used for measuring the inequality status in capacity to pay and household health payments. The concentration indicator was calculated as bellow:

where Xi represents the cumulative percentage of the population-based on income, and Yi represents cumulative percentage of household capacity to pay (40).

Results

The results of this study indicated that, in studied households, the share of household health costs compared to non-health costs and also food expenditures is very low. The proportion of health payments from household’s capacity to pay, gross expenditures and total out-of-pocket payments compared to proportion of out-of-pocket payments for outpatient and inpatient services from the capacity to pay, gross expenditures and total out-of-pocket payments for health among studies households is very high (Table 1).

Table 1 . The average (in percent)of health expenditures in the studied households.

| Cost indexes |

Total household |

Utilized healthcare for households |

| The share of out-of-pocket health payments from households capacity to pay | 7.7 | 9.45 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for outpatient services from capacity to pay | 0.7 | 1.09 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services from capacity to pay | 3 | 4.45 |

| The share of health prepayments from households capacity to pay | 4 | 3.9 |

| The share of out-of-pocket health payments from households gross costs | 5 | 5.81 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for outpatient services from households gross costs | 0.5 | 0.67 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services from households gross costs | 2 | 2.73 |

| The share of health prepayments from households gross costs | 2.5 | 2.41 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for outpatient services from total out-of-pocket health payments |

9.6 |

11.6 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services from total out-of-pocket health payments |

38.4 |

47 |

| The share of health prepayment from total health out-of-pocket payments | 52 | 41.4 |

| The share of mandatory health insurance from total health prepayments | 71.1 | 70.4 |

| The share of voluntary health insurance from total health prepayments | 28.9 | 29.6 |

| The share of non-health costs from total gross costs | 95 | 66.27 |

| The share of food costs from total gross costs | 34.1 | 33.73 |

| The share of capacity to pay from total gross costs | 60.4 | 61.39 |

The results of the study showed that, among the all households in this study, the highest rate of out-of-pocket payments for inpatient to household’s capacity to pay, the rate of out-of-pocket payments for heath to gross costs and the out-of-pocket payments for health per capita are related to fourth quintiles. Though in terms of other costs the first quintile is allocated the maximum amount (Table 2).

Table 2 . The average (in percent) of health expenditures in studied households based on quintile .

|

Quintiles Expenditures indices |

The Poorest | 2 | 3 | 4 | The Richest |

|

The share of out-of-pocket health payments from households capacity to pay |

9.31 | 8.1 | 6.36 | 7.25 | 1.4 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payment for outpatient services From capacity to pay | 1.02 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.07 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services From capacity to pay | 2.67 | 3 | 2.4 | 6.3 | 0.26 |

| The share of health prepayments from households capacity to pay | 5.62 | 4.43 | 3.27 | 0.35 | 1.07 |

| The share of out-of-pocket health payment from households gross costs | 4.48 | 4.9 | 4.48 | 5.8 | 1.2 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for outpatient services from households gross costs | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.05 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services from households gross costs | 1.3 | 1.82 | 1.7 | 5 | 0.22 |

| The share of health prepayments from households gross costs | 2.68 | 2.68 | 2.3 | 0.32 | 0.93 |

| The share of non-health costs from total gross costs | 95.52 | 95.52 | 95.52 | 94.2 | 98.8 |

| The share of food costs from total gross costs | 40.64 | 34 | 29.8 | 29.9 | 14.13 |

|

Per capita out-of-pockethealth payments (in US dollars) |

21.48 | 33.39 | 55.29 | 105.04 | 30.61 |

| Per capita cost (in US dollars) | 534.25 | 666.57 | 1397.37 | 2173.65 | 2936.8 |

The results showed that the fifth quintile in terms of cost per capita and the share of non-health costs from total gross costs is the forerunner. In terms of another cost indices the first quintile is allocated the maximum amount (Table 3).

Table 3 . The average (in percent)of health expenditures in studied households with utilized health care based on quintile .

|

Quintiles Expenditures indices |

The poorest | 2 | 3 | 4 |

The richest |

| The share of out-of-pocket health payments from households capacity to pay | 12.07 | 10.2 | 7.9 | 9.6 | 1.91 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for outpatient services from capacity to pay | 1.75 | 1 | 1.08 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services from capacity to pay | 4.58 | 4.53 | 3.75 | 8.47 | 0.41 |

| The share of health prepayments from households capacity to pay | 5.74 | 4.67 | 2.67 | 0.33 | 1.397 |

| The share of out-of-pocket health payments from households gross costs | 5.9 | 6.15 | 5.5 | 7.56 | 1.62 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for outpatient services from households gross costs | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.08 |

| The share of out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services from households gross costs | 2.22 | 2.73 | 2.6 | 6.69 | 0.35 |

| The share of health prepayments from households gross costs | 2.83 | 2.81 | 2.15 | 0.24 | 1.19 |

| The share of non-health costs from total gross costs | 94.1 | 93.85 | 94.5 | 92.44 | 98.38 |

| The share of food costs from total gross costs | 40.3 | 33.17 | 30.63 | 34.22 | 14.05 |

| Per capita out-of-pocket health payments (in US dollars) | 25.83 | 42.48 | 65.10 | 147.20 | 35.57 |

| Per capita cost (in US dollars) | 465.63 | 658.88 | 1269.52 | 2083.86 | 2486.17 |

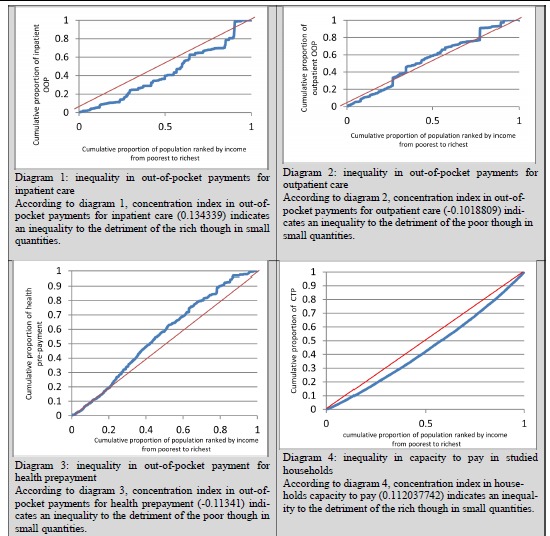

Inequality for out-of-pocket payments for health care and capacity to pay in total studied households is shown in Fig.1.

Fig. 1 .

Inequality in studied households health care out-of-pocket payments and capacity to pay

The average of out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services was 1861.11 US$. Proportion of hospital bill, transportation costs, medical appliance from outside of hospital, rehabilitation services, consultation services, drug provision from outside of hospital and informal payments from total payments for inpatient expenditures were estimated to be 76.51%, 2.1%, 7.45%, 3.95%, 0.05%, 7.54% and 2.4% respectively.

The expenditures of healthcare services mainly are financed from savings and taking loans and borrowing is in the second position (Table 4).

Table 4 . Frequency of households’ strategies for utilized health care payments .

|

Selling the assets |

Loans/ borrowing |

Savings |

Institutional/Organizations/ families support |

Current income |

Other places |

Total |

| 8.7 | 17.1 | 50.5 | 12.2 | 1.5 | 10 | 100 |

Discussion

In health care system, equality in financing and eliminating inequalities in using the health care services, are challenging and complicated issues which needs rapt attention from the politicians, planners, providers and users’.

Because of the out-of-pocket payments and inequalities in health care payments most of poor households do not use health care services. In many cases as long as the illness is not serious, individuals in low socio economic situation, do not follow health care. In Iran, prescription drugs, as well as over the counter (OTC) drugs are easily accessible from the pharmacies and drug supply centers. The phenomenon of self-medication especially in chronic patients may be as a result of this situation. Therefore calculated and estimated statistics must notice to these facts and real incidence of catastrophic expenditures among the poor.

The results of the present study indicated that, in studied households, the share of out-of-pocket payments for health care from the households’ gross costs is 5% and the share of out-of-pocket payments for health from the households’ capacity to pay is 7.7%.Our analysis indicated the inequality in out-of-pocket payments for outpatient health care services, inpatient health care services and health prepayments, using the concentration curve and concentration index. The results of this study indicated that, by increasing the household’s income, out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services will increase. Payments for outpatient services and prepayments for health care are mostly related to the poor. In the other word, the poor allocate a large part of their income to outpatient services and prepayments for health care. This issue is in conflict with the motto of the World Health Organization (WHO) to support the households against the health care costs and responding to citizens’ expectations. These ratios are the most used measures for evaluating equality in out-of-pocket payments in experimental studies. The growing trend of out-of-pocket payments for health care in Iran indicates that, the poor can easily access to health insurance plans without paying so much. The study of Võrk et al (2010) indicated that, in 2000 the ratio of out-of-pocket payments for health care services to gross costs is 2.6% and in 2007 it was 3.6% (41). The Falkingham and colleagues’ study (2012) indicated that, the outpatient health care costs is 34% of per capita household expenditure in the poorest quintile compared to the 16% of per capita expenditure in the richest quintile and 24% of gross costs among all households (42). The report of improving the equality in accessing the health care services in Asia-Oceania (2007) indicated that, the ratio which household spend for health care is more than 5% in Bangladesh, China, India and Vietnam. This ratio is about 2 % in Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka and Thailand (43). The study of Yardim et al (2010) indicates that the share of out-of-pocket payments for health care costs in monthly household’s gross costs is 2.18% and of household’s capacity to pay is 2.71% (21). The difference in sample size, expenditure assessment tools, research methods, recoveries period; using the outpatient and inpatient health care and recording the related costs, different social and economic structures, different health systems in countries, etc can cause the difference between our study and other studies.

According to this study, inequality in capacity to pay and also household’s income indicates the inequality in distribution economic potential and income to benefit the rich.

According to this study, the average out-of-pocket payments for inpatient and outpatient health care services are 44.33US$ and 1,861.11US$ per year, respectively. The indirect costs such as transportation costs, informal payments etc. include about 7.8% of out-of-pocket payments for outpatient services and 92.2% of related costs for visiting physician, drug prescriptions, diagnostic and imaging procedures. Among the out-of-pocket payments for inpatient services, hospital bills with 76.51% are the highest amount. About 14% of the out-of-pocket payments allocated to provide medicines and medical supplies preparation from outside the hospital, and close to 2% of out-of-pocket payments are concerned to be informal payments to physicians and medical human resources. Evidence shows that in Iran one of the important issues in the field of health financing that imposes heavy burdens on households, is high proportion of out-of-pocket from total health costs. According to the Ministry of Health report, the private sector has a higher share in financing health expenditures compared with governmental sector (44). Private sector financing includes out-of-pocket payments and direct participation of households (more than 96%) in health costs (45). From the equality perspective, private financing based on household’s out-of-pocket payments, seems not to be pleasant (22). WHO has estimated the average amount of out-of-pocket payments for health care in developing countries to be 45% of total health expenditures (46).Participation of households for health care financing through out-of-pocket payments in Iran (more than 50%) is more than developing countries. In Iran public and private sector insuring companies are not working efficiently and some of the health services are covered. On the other hand, according to the WHO report, poor management in health insurance has resulted service overlap in Iran (47). In some cases, despite the determination of tariffs of inpatient and outpatient health care services, physicians present the patients with bill higher than the tariffs. Out-of-pocket payments will increases the possibility of encountering catastrophic costs and leading to poverty and there are dire consequences. People, who do not need to the emergency health care, usually postpone or completely forget their health care needs. In Iran the hospitals’ payment systems is based on fee for services (48).

Xu et al, (2007) stated that "there is no universal formula to help poor countries to reduce out-of-pocket payments against health expenditures." There is no universal formula to help poor countries to increase the emphasis over prepayments and to reduce out-of-pocket payments. Countries at different stages of economic, social and political development have different problems thus they need different solutions. Nevertheless, many poor countries are less able to provide enough budgets on a national basis for estimating the health needs in middle or short time period. In these countries governments have limited ability to collect taxes or health insurance premium, because people are poor and many of them work at private sector (49).

In Iran sanction-borne inflation in health and also other economic sectors in recent years has caused financial crisis especially on out-of-pocket payments for health and households capacity to pay.

Our study results also showed that households used various sources and strategies for healthcare payments.About8.7% of cases held sale of their assets, 17.1% took on loan, 50.5%usedsavings, 12.2% to supported institutions/organizations and relatives, 1.5% were concerned about current income, and 10% concerned other reasons.

According to Daneshkohan et al, study (2011), due to the health care costs, 49.2% of households are debtor, 21.7% of them sold their assets and 15% of them used their savings (50). According to Xu et al, (2003), in order to provide health care costs, 19% of households had to use loans or borrow (8,7). In Cambodia households could not payback the received loans and they finally are enforced to sell their land assets (51). In a study by Garcia et al. (2003), 35% of all cases in received financial/economic support from relatives and close friends, while 8.7% borrow for covering the costs of hospital (52). Being in debt caused by loans and borrowing to pay the health care costs were confirmed in the study of Ensor et al, (1996) and Whitehead et al (2001) (53,54). Based on the Gotsadze et al, study (2005) some strategies were reported to health care payments: loans, borrowing, selling assets especially by the poor (55). In the studies of Skarbinski et al, (2002) Kamolratanakul et al (1999), selling the assets for providing the health care costs, is confirmed too (56, 57). Xu et al, indicated that, some of households have to sell their assets, in order to pay their loans back. Selling assets, will lead to low level life and standard of living for the family (49).Empirical evidence show that people are actually able to prevent a decline in their non-medical expenditure (reducing these costs for health care services) by selling assets or borrowing. The clear message would be that the people use various strategies to protect their life against treatment expenditures, and unwanted health expenditures. Failure in estimation endangers utilization and financial protection from people against the health costs and causes disaster and poverty, so far as, catastrophic expenditure will become a disturbing issue (7). Some studies suggest that the high costs of health may cause pass up from other essential expenses such as food, clothing, housing purchase, and children education (58, 59).

Loans and borrowing help households to be able to delay costs or divide the min to several periods, although; because of the interest rate additional bills of the loan will be paid in the future. This issue will also pull the vulnerable households in to poverty. We believe that an exemption policy on field of participation schemes in health expenditure should be a safety network for the poor and disadvantaged groups, thus, many needy people could have access to essential health care services.

Conclusion

According to this study, the regressive system is dominant in health financing in Iran and it indicates that the poor spends huge proportion of their capacity to pay for inpatient, outpatient health care and prepayments compared to the rich. The study showed the inequality and weakness of health care system in financing and protecting the poor households against the unwanted health care costs. Thus, of important concerns are supporting vulnerable groups in society in order to reduce the out-of-pocket payments for health care and increasing the household’s capacity to pay through government support in order to improve the household economic potential.

Acknowledgments

The researchers appreciate and thank all the households who helped this study.

Cite this article as: Rezapour A, Ebadifard Azar F, Azami Aghdash S, Tanoomand A, Ahmadzadeh N, Sarabi Asiabar A. Inequity in household's capacity to pay and health payments in Tehran-Iran-2013. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2015 (10 August). Vol. 29:245.

References

- 1.Bagheri Lankarani K, Lotfi F, Karimian Z. introduction to health equity. health policy research center, shiraz navid. 2010;7(2):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida-Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2002;56(9):647–52. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.9.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinhardt UE, Cheng Tm. The world health report 2000-Health systems: improving performance. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78(8):1064. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Auerbach AJ, Card D, John M. Quigley: Public ploicy and the income distribution, chapter7:’ the measurement and Evolution of Health Inequity: Evidence from The U.S. Medicare Population’, Russel Sage Foundation, New york, 2006.

- 5.Wagstaff A. Reflections on and alternatives to WHO's fairness of financial contribution index. Health Economics. 2002;11(2):103–15. doi: 10.1002/hec.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Folland S, Goodman A, Stano M. Economics of health and health care. 2006.

- 7.Wagstaff A. Measuring financial protection in health. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJL. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. The Lancet. 2003;362(9378):111–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin A, Valentine N, Brown C, Loewenson R, Solar O, Brown H. et al. The Commission on Social Determinants of Health: Tackling the social roots of health inequities. PLoS medicine. 2006;3(6):e106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Asefzade S, Rezapoor A. Health care management. qazvin: hadise emrooz; 2012.

- 11. Asefzade S. Principales of Health Economics. 3 ed. Qazvin: Hadise-emrouz 2010.

- 12. Fourth Five-Year Development Plan set. tehran: presidence, d.f.S.P.a.M.o., 2005.

- 13. Razavi SM, Hassanzadeh A, Bassmanji K. Equity in Financing Contribution in health system. Tehran; Andishmand Publisher, 2005.

- 14.Makinen M, Waters H, Rauch M, Almagambetova N, Bitran R, Gilson L. et al. Inequalities in health care use and expenditures: empirical data from eight developing countries and countries in transition. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78(1):55–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Mechbal A, Murray CJL. The world health surveys. Health systems performance assessment: debates, methods and empiricism Geneva, World Health Organization 2003;797.

- 16. Households Budjet Questionaire 2009; Available from:http://salnameh.sci.org.ir.

- 17. Culyer AJ. The dictionary of health economics: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2008.

- 18.Bredenkamp C, Mendola M, Gragnolati M. Catastrophic and impoverishing effects of health expenditure: new evidence from the Western Balkans. Health policy and planning. 2011;26(4):349–56. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salti N, Chaaban J, Raad F. Research Health equity in Lebanon: a microeconomic analysis. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.López-Cevallos DF, Chi C. Health care utilization in Ecuador: a multilevel analysis of socio-economic determinants and inequality issues. Health policy and planning. 2010;25(3):209–18. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yardim MS, CilingirogluN CilingirogluN, Yardim N. Catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment in Turkey. Health policy. 2010;94(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gotsadze G, Zoidze A, Rukhadze N. Household catastrophic health expenditure: evidence from Georgia and its policy implications. BMC health services research. 2009;9(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Angel-Urdinola D, Cortez R, Tanabe K. Equity, access to health care services and expenditures on Health in Nicaragua: World Bank; 2008.

- 24.Morris S, Sutton M, Gravelle H. Inequity and inequality in the use of health carein England: an empirical investigation. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(6):1251–66. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regidor E, Martínez D, Calle ME, Astasio P, Ortega P, Domínguez V. Socioeconomic patterns in the use of public and private health services and equity in health care. BMC health services research. 2008;8(1):183. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu CP, Whynes DK, Sach TH. International Journal for Equity in Health. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2008;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendoza-Sassi R, Béria JU, Barros AJD. Outpatient health service utilization and associated factors: a population-based study. Revista de saúde pública. 2003;37(3):372–8. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102003000300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunlop S, Coyte PC, McIsaac W. Socio-economic status and the utilisation of physicians' services: results from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51(1):123–33. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sibley LM, Weiner JP. An evaluation of access to health care services along the rural-urban continuum in Canada. BMC health services research. 2011;11(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De La Hoz KF, Leon DA. Self-perceivedhealth status and inequalities in use of health services in Spain. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1996;25(3):593–603. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.3.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Doorslaer E, Koolman X, Puffer F. Equity in the use of physician visits in OECD countries: has equal treatment for equalneed been achieved. Measuring up: improving health systems performance in OECD countries. 2002:225–48. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szwarcwald CL, Souza-Júnior PRB, Damacena GN. Socioeconomic inequalities in the use of outpatient services in Brazil according to health care need: evidence from the World Health Survey. BMC health services research. 2010;10(1):217. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maziak W, Ward KD, Mzayek F, Rastam S, Bachir ME, Fouad MF. et al. Mapping the health and environmental situation in informal zones in Aleppo, Syria: report from theAleppo household survey. International archives of occupational and environmental health. 2005;78(7):547–58. doi: 10.1007/s00420-005-0625-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotchkiss DR, Hutchinson PL, Malaj A, Berruti AA. Out-of-pocket payments and utilization of health care services in Albania: Evidence from three districts. Health policy. 2005;75(1):18–39. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bago d’Uva T, Jones AM, Van Doorslaer E. Measurement of horizontal inequity in health care utilisation using European panel data. Journal of health economics. 2009;28(2):280–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mangano A. An analysisof the regional differences in health care utilization in Italy. Health & Place. 2010;16(2):301–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hjortsberg C. Why do the sick not utilise health care? The case of Zambia. Health Economics. 2003;12(9):755–70. doi: 10.1002/hec.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rous JJ, Hotchkiss DR. Estimation ofthe determinants of household health care expenditures in Nepal with controls for endogenous illness and provider choice. Health Economics. 2003;12(6):431–51. doi: 10.1002/hec.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagstaff A, Doorslaer Ev. Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: with applications to Vietnam 1993–1998. Health Economics. 2003;12(11):921–33. doi: 10.1002/hec.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown MC. Using Gini-style indices to evaluate the spatial patterns of health practitioners: theoretical considerations and an application based on Alberta data. Social Science & Medicine. 1994;38(9):1243–56. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Võrk A, Saluse J, Habicht J. Income-related inequality in health care financing and utilization in Estonia 2000-2007. 2009.

- 42.Falkingham J, Akkazieva B, Baschieri A. Trends in out-of-pocket payments for health care in Kyrgyzstan, 2001–2007. Health policy and planning. 2010;25(5):427–36. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Durairaj V. Enhancing equity in access to health care in the Asia-Pacific region: Remediable inequities. report prepared for the United Nations Regional Thematic Working Group on Health, May, Bangkok, WHO and UNFPA. 2007.

- 44. Report of budget and financial planning department of ministry of health. Tehran,Iran 2010.

- 45. Ebadifard azar f, Rezapoor a. health care Financial management. 1 ed. tehran: ebadifar; 2012.

- 46.Lu C, ChinB ChinB, Li G, Murray CJL. Limitations of methods for measuring out-of-pocket and catastrophic private health expenditures. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87(3):238–44D. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.054379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Regional Health systems observatory. World Health organization, Health System profile:Islamic Republic of Iran, 2006.

- 48. Ebadifard Azar F, Rezapoor A. health care economics. 1 ed. tehran: ebadifar; 2010.

- 49.Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, Aguilar-Rivera AM, Musgrove P, Evans T. Protecting households from catastrophic health spending. Health affairs. 2007;26(4):972–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daneshkohan A, Karami M, Najafi F, Matin BK. Household catastrophic health expenditure. Iranian journal of public health. 2011;40(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damme WV, Leemput LV, Hardeman W, Meessen B. Out‐of‐pocket health expenditure and debt in poor households: evidence from Cambodia. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2004;9(2):273–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rocha-García A HPP, Ruiz-Velazco S, Avila-Burgos L, Marín-Palomares T, Lazcano-Ponce E. health care for hospitalization of insured children diagnosed with leukemia, in two hospitals in Mexico. Mexico: 2003. [PubMed]

- 53.Ensor T, San PB. Access and payment for health care: the poor of Northern Vietnam. The International journal of health planning and management. 1996;11(1):69–83. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1751(199601)11:1<69::AID-HPM414>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitehead M, Dahlgren G, Evans T. Equity and health sector reforms: can low-income countries escape the medical poverty trap? The Lancet. 2001;358(9284):833–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05975-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gotsadze G, Bennett S, Ranson K, Gzirishvili D. Health care-seeking behaviour and out-of-pocket payments in Tbilisi, Georgia. Health policy and planning. 2005;20(4):232–42. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skarbinski J, Walker HK, Baker LC, Kobaladze A, Kirtava Z, Raffin TA. The burden of out-of-pocket payments for health care in Tbilisi, Republic of Georgia. JAMA: the journal ofthe American Medical Association. 2002;287(8):1043–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.8.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamolratanakul P, Sawert H, Kongsin S, Lertmaharit S, Sriwongsa J, Na-Songkhla S. et al. Economic impact of tuberculosis at the household level. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and LungDisease. 1999;3(7):596–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Paying for Health Services. World Health Organization fact sheet no 320, 2007.

- 59. World Health O. Toolkit on monitoring health systems strengthening. Medical products, vaccines and technologies: a toolkit for countries Geneve: WHO. 2009.