SUMMARY

Autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) can improve outcomes for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) patients, yet relapses are frequent. We hypothesized that high-dose anti-CD20 radioimmunotherapy (RIT)-based conditioning could improve results in this setting. We thus assessed 162 consecutive patients with MCL at our centre undergoing ASCT following high-dose RIT-based (n = 61) or standard (n = 101) conditioning. RIT patients were less likely to be in first remission (48% vs 72%; p = 0.002), be in complete remission (CR) (26% vs 61%; p < 0.001) and have chemosensitive disease (84% vs 96%; p = 0.006). RIT-based conditioning was associated with a reduced risk of treatment failure (hazard ratio [HR] 0.40; p = 0.001) and mortality (HR 0.49; p = 0.01) after adjusting for these imbalances. This difference increased as disease status worsened (from CR to partial remission to stable/progressive disease), with respective HRs of 1.14, 0.53 and 0.04 for mortality, and 0.66, 0.36 and 0.14 for treatment failure. RIT-based conditioning appears to improve outcome following ASCT for MCL patients unable to achieve CR after controlling for imbalances in important risk factors. These data support the further study of RIT and radiation-based strategies in a risk-adapted approach to ASCT for persistent MCL.

Keywords: non-Hodgkin lymphoma, stem cell transplantation, antibody therapy, radiotherapy

Introduction

Despite advances in treatment, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is considered to be incurable with standard approaches (Dreyling & Hiddemann, 2009). For fit patients with this diagnosis, combination cytotoxic chemotherapy with rituximab followed by high-dose therapy (HDT) and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in first remission is commonly offered (Dreyling et al, 2005; Geisler et al, 2008; Damon et al, 2009; Le Gouill et al, 2012; Delarue et al, 2013). Unfortunately, this aggressive strategy yields a median progression-free survival (PFS) of only about 5-7 years. When ASCT is used for relapsed/refractory disease, the outcomes are generally worse, resulting in a median PFS closer to 1-2 years (Cassaday et al, 2013; Fenske et al, 2014). Furthermore, ASCT is usually not offered to patients with certain high-risk clinical features (e.g., chemotherapy-refractory disease). Thus, methods to reliably prolong remission duration following ASCT are needed.

One potential strategy to achieve this goal is through the use of radioimmunotherapy (RIT), based on the exquisite radiosensitivity of B-cell malignancies. Prospective studies of anti-CD20 RIT have demonstrated the efficacy of this approach in newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory MCL (Zelenetz et al, 2006; Wang et al, 2009; Smith et al, 2012). Our group and others have taken advantage of the clear dose-response effect of radiation in haematopoietic malignancies and maximized the potential anti-tumour efficacy of RIT by escalating the dose of anti-CD20 RIT as part of high-dose conditioning regimens prior to ASCT for a variety of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (B-NHL), either alone or in combination with chemotherapy (Press et al, 1993; Press et al, 2000; Nademanee et al, 2005; Ferrucci et al, 2007; Gopal et al, 2007; Devizzi et al, 2008; Krishnan et al, 2008; Winter et al, 2009; Shimoni et al, 2012; Vose et al, 2013; Gopal et al, 2014). High-dose RIT is made possible by the limited non-haematological toxicity of this technique and the ability to restore haematopoiesis after myeloablation with ASCT. Randomized studies of standard-dose anti-CD20 RIT added to chemotherapy-based HDT have provided mixed results for relapsed/persistent diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, but may have been limited by the relatively small dose of radiation absorbed to tumour sites (Shimoni et al, 2012; Vose et al, 2013). In contrast, retrospective comparisons of ASCT utilizing high-dose RIT vs conventional ASCT suggest improved outcomes with the RIT-based approach in patients with relapsed/refractory indolent and aggressive B-cell lymphoma (Press et al, 2000; Gopal et al, 2003). Dose-escalation of RIT in MCL has not yet been explored in a comparative fashion.

We hypothesized that incorporating high-dose anti-CD20 RIT into the conditioning therapy for ASCT could improve outcomes for patients with MCL based on the known radiosensitivity of B-NHL. We also predicted that the maximal benefit would be observed in patients with persistent disease or high-risk features, such as chemorefractory disease, where the crossfire amplification could augment localization of the absorbed dose to haematolymphoid sites and radiation-induced anti-tumour activity would have the most benefit.

Patients and Methods

Study Cohort

Consecutive patients older than 18 years with MCL receiving ASCT between November 1995 and May 2011 at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC), University of Washington Medical Center and Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (Seattle, Washington, USA) were included. Patients who received a planned tandem autologousallogeneic transplant or a syngeneic transplant were excluded. All patients who were treated on an investigational study signed a consent form approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the University of Washington and/or the Institutional Review Board of the FHCRC in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, separate institutional approval was obtained for this analysis to retrospectively gather data from patient records and databases.

Study Variables

Baseline demographic information from the time of diagnosis (including age, sex, presence of B symptoms [fever, night sweats, or >10% unintentional weight loss]) and time of ASCT (including number and type of prior chemotherapy regimens, prior treatment with rituximab and disease status) was collected. MCL international prognostic index (MIPI) scores were calculated using data from diagnosis as well as prior to conditioning therapy for ASCT (Hoster et al, 2008). Disease response, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were defined by standard criteria (Cheson et al, 2007). Patients were considered to have chemosensitive disease if they achieved either a complete (CR) or partial remission (PR) to the most recently administered systemic therapy prior to transplantation.

Treatment

The conditioning regimens used were categorized as either “conventional” or “RIT-based.” Conventional conditioning regimens included BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan), BuMelT (busulfan, melphalan and thiotepa) and 12 Gy of total body irradiation (TBI) plus cyclophosphamide with or without etoposide, as previously described (Cooney et al, 2003; Gutierrez-Delgado et al, 2003). For those treated with RIT-based conditioning, all patients received iodine-131 (131I) conjugated to an anti-CD20 antibody (tositumomab). RIT was administered alone or in combination with escalating doses of fludarabine or with cyclophosphamide and etoposide on prospective single-arm clinical trials (FHCRC Protocols 915, 1366, 1368, and 1943), as previously described (Press et al, 2000; Gopal et al, 2007; Gopal et al, 2014). Decisions to pursue conventional or RIT-based conditioning were left to the discretion of the treating physicians, but were probably impacted by perceived outcomes with a conventional approach and the availability for timely treatment on one of the above RIT trials. Other than the eligibility criteria for the respective protocols, no formal selection process was used to determine what treatment patients received.

Statistical Considerations

Frequencies of characteristics between groups were compared using a chi-square test, while means were compared using a Wilcoxon rank-sum text. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate the probabilities of OS and PFS from the time of ASCT. The statistical significance of differences in event rates was evaluated with the Cox proportional hazards regression model. A two-step process was used in variable selection for the final model. First, all variables were tested individually in a univariate analysis. Subsequently, the following covariates were tested via backwards selection for the multivariate models: gender, age, blastoid histology, B symptoms, rituximab within 3 months of ASCT, disease status at ASCT, chemosensitive disease, number of prior therapies, ASCT in first remission, MIPI at ASCT and peripheral blood or bone marrow involvement at ASCT.

To account for imbalanced covariates in subgroups, adjusted Kaplan-Meier plots were generated (Storer et al, 2008). To investigate if the treatment effect on PFS and OS was similar for each level of each covariate, an interaction test was performed separately for each reasonable interaction (e.g., interaction between chemosensitivity and ASCT conditioning) in each model. Conclusions were based on the assumption that the treatment effect was the same for each level of each covariate. All p-values are based on the Wald statistic and are two-sided, with results < 0.05 deemed statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

From November 1995 to May 2011, we identified 162 patients with MCL that received ASCT. The baseline characteristics of these patients are described in Table I. The majority of patients were male and aged over 50 years. Nearly half had low-risk MIPI scores at the time of diagnosis and 9% (n = 14) had blastoid histology. The most common front-line induction strategies were either CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; 55%; n = 89) or hyperCVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine; 36%; n = 59). Nearly all patients (92%; n = 149) received rituximab within 3 months of ASCT, either as part of their front-line or salvage therapy. ASCT was used to consolidate first remission in 63% (n = 102).

Table I.

Baseline demographics.

| Patient Characteristic | Total (N = 162) | RIT (N = 61) | Control (N = 101) | P+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.42 | |||

| Male | 133 (82%) | 52 (85%) | 81 (80%) | - |

| Female | 29 (18%) | 9 (15%) | 20 (20%) | - |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 0.06 | |||

| Median | 56 | 57 | 55 | - |

| Range | 35-70 | 35-69 | 37-70 | - |

| Greater than 60 years | 42 (26%) | 12 (20%) | 30 (30%) | 0.16 |

| B symptoms at diagnosis | 42 (26%) | 12 (20%) | 30 (30%) | 0.16 |

| MIPI at diagnosis | 0.24 | |||

| Low risk (< 5.7) | 71 (44%) | 21 (34%) | 50 (50%) | - |

| Intermediate risk (all others) | 36 (22%) | 16 (26%) | 20 (20%) | - |

| High risk (≥ 6.2) | 19 (12%) | 5 (8%) | 14 (14%) | - |

| Missing data | 36 (22%) | 19 (31%) | 17 (17%) | - |

| Histological subtype | 0.70 | |||

| Blastoid | 14 (9%) | 6 (10%) | 8 (8%) | - |

| Other | 112 (69%) | 42 (69%) | 70 (70%) | - |

| Missing data | 36 (22%) | 13 (21%) | 23 (23%) | - |

| Front-line induction therapy | 0.02 | |||

| HyperCVAD | 59 (36%) | 14 (23%) | 45 (45%) | - |

| CHOP | 89 (55%) | 40 (66%) | 49 (49%) | - |

| Other† | 14 (9%) | 7 (11%) | 7 (7%) | - |

| Disease status at ASCT | <0.001 | |||

| CR | 78 (48%) | 16 (26%) | 62 (61%) | - |

| PR | 68 (42%) | 36 (59%) | 32 (32%) | - |

| SD/PD | 16 (10%) | 9 (15%) | 7 (7%) | - |

| Chemosensitive‡ | 148 (91%) | 51 (84%) | 97 (96%) | 0.006 |

| Timing of ASCT | 0.002 | |||

| First remission | 102 (63%) | 29 (48%) | 73 (72%) | - |

| Relapsed/refractory | 60 (37%) | 32 (52%) | 28 (28%) | - |

| Number of prior therapies | 0.007 | |||

| Median | 1 | 2 | 1 | - |

| Range | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-5 | - |

| Rituximab within 3 months of ASCT | 149 (92%) | 52 (85%) | 97 (96%) | 0.01 |

| MIPI at ASCT | 0.31 | |||

| Low risk (< 5.7) | 119 (73%) | 42 (69%) | 77 (76%) | - |

| Intermediate risk (all others) | 35 (22%) | 16 (26%) | 19 (19%) | - |

| High risk (≥ 6.2) | 6 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (5%) | - |

| Missing data | 2 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| PB/BM Involvement at ASCT | 0.38 | |||

| Positive | 30 (19%) | 13 (21%) | 17 (17%) | - |

| Negative | 110 (68%) | 38 (62%) | 72 (71%) | - |

| Missing data | 22 (14%) | 10 (16%) | 12 (12%) | - |

| Conditioning regimen used | - | |||

| Chemotherapy only | 40 (25%) | - | 40 (40%) | - |

| Chemoradiation | 61 (38%) | - | 61 (60%) | - |

| RIT only | 7 (4%) | 7 (11%) | - | - |

| RIT + chemotherapy | 54 (33%) | 54 (89%) | - | - |

RIT, radioimmunotherapy; MIPI, mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index; HyperCVAD, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow

P-values are from comparisons between the RIT and control groups.

RIT group: cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (CVP) (4); cyclophosphamide (1); fludarabine-based combination (1); and ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide (1). Control group: CVP (1), chlorambucil (1), maxi-CHOP (1), rituximab (2) and fludarabine-based combination (2).

The number of patients with chemosensitive disease is not the same as the cumulative number in remission (CR + PR) for the following reasons: In the RIT group, 1 patient with chemosensitive disease was in untested relapse and 2 patients with chemorefractory disease were in remission only after local interventions (1 underwent splenectomy, 1 received salvage radiotherapy). In the control group, 4 patients with chemosensitive disease were in untested relapse and 1 patient with chemorefractory disease was in PR only after salvage radiotherapy.

When divided by conditioning regimen, 38% (n = 61) received RIT-based HDT, with most of these (89%; n = 54) receiving RIT in combination with chemotherapy (either fludarabine [n = 20] or high-dose cyclophosphamide and etoposide [n = 34]). RIT patients received a median of 19.8 GBq (range: 7.6-40.7 GBq) of 131I to deliver a median of 25 Gy (range: 20-27 Gy) absorbed dose to critical organs. ASCT in the RIT group occurred throughout the range of this study period (i.e., July 1996 to December 2009). In the conventional HDT group (the “control” group), 60% (n = 61) received TBI in combination with chemotherapy (high-dose cyclophosphamide with or without etoposide). The remaining 40% (n = 40) received HDT with chemotherapy only (either BEAM [n = 35] or BuMelT [n = 5]).

Table I depicts the differences in characteristics between the RIT and control groups. Several high-risk clinical features were more common among the RIT-treated patients, including ASCT for relapsed/refractory disease (p = 0.002), greater number of systemic therapies prior to ASCT (p = 0.007) and more advanced disease status at ASCT (p < 0.001). Further, patients in the control group were significantly more likely to have chemosensitive disease at the time of ASCT (p = 0.006). Patients in the control group were also significantly more likely to have received rituximab within 3 months of ASCT (p = 0.01). HyperCVAD was used as front-line therapy nearly twice as often in the control group as the RIT group (p = 0.02). Median age at diagnosis of patients in the RIT group (57 years) was slightly higher than that in the control group (55 years), a difference that was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). There was no apparent difference in MIPI scores between the two groups.

Overall and Progression-Free Survival

Univariate comparison

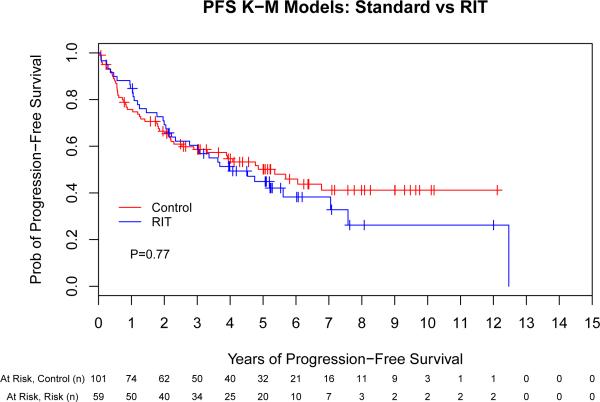

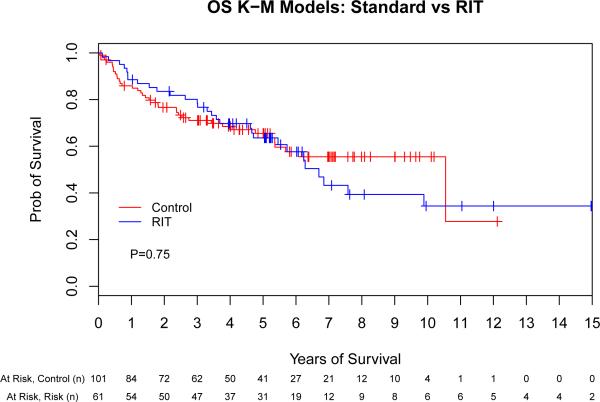

The unadjusted PFS and OS for the control and RIT sub-groups by Kaplan-Meier analysis are shown in Fig 1. Median follow-up from ASCT for all surviving patients was 61 months, while the median time to either last follow-up or death for all patients was 52 months. The 2-year, 5-year and median PFS was 66%, 49% and 64 months (respectively) for the control group compared to 70%, 45% and 54 months (respectively) for the RIT group (hazard ratio [HR] 1.07 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.69-1.64], p = 0.77). The 2-year, 5-year and median OS were 76%, 64% and 126 months (respectively) for the control group compared to 82%, 62% and 80 months (respectively) for the RIT group (HR 1.08 [95% CI, 0.67-1.76], p = 0.75). In summary, the univariate Cox regression models indicate that the hazards of treatment failure (i.e., death or relapse) and mortality in the RIT group were similar to those in the control group. We also subdivided the control group into chemotherapy- and TBI-based conditioning groups; in an unadjusted comparison to RIT, there were no significant differences in either PFS (p = 0.29) or OS (p = 0.89; data not shown).

Fig 1.

Unadjusted outcomes for patients with mantle cell lymphoma following autologous stem cell transplantation with or without high-dose radioimmunotherapy-based conditioning. Progression-free (A) and overall survival (B) for all patients included in this analysis, depicted as Kaplan-Meier curves. P-values are the results of Cox proportional hazard models. Tick marks represent censored events. Prob, probability; RIT, radioimmunotherapy.

Multivariate comparison

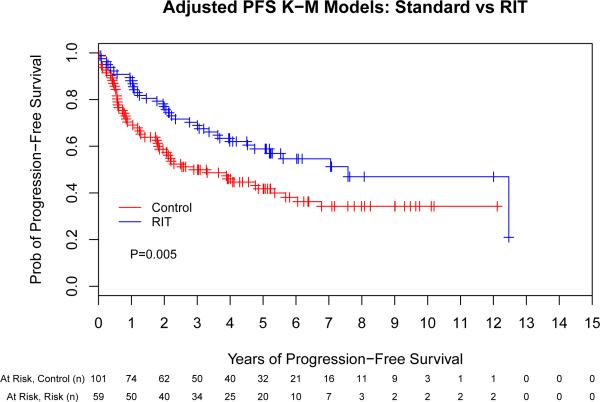

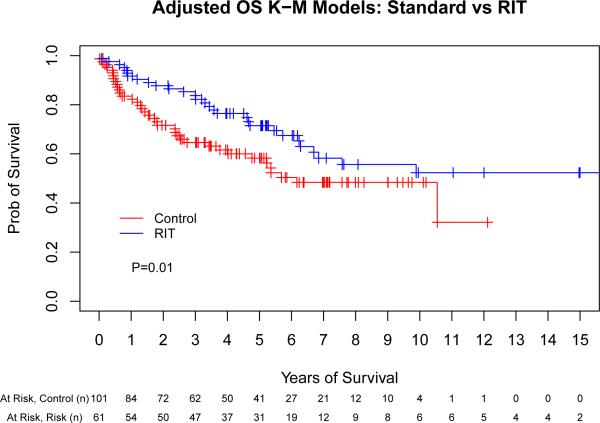

We performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis adjusting for pre-transplant factors that were independently associated with outcome (chemosensitivity, remission status at ASCT, ASCT in first remission and age). This allowed us to take in to account the substantial baseline differences in the above groups in order to obtain a more precise estimate of the true treatment effect. This evaluation found that patients conditioned with high-dose RIT were significantly less likely to suffer treatment failure or death compared to the control group (HR 0.40 [95% CI, 0.23- 0.69], p = 0.001; HR 0.49 [95% CI, 0.28-0.86], p = 0.01, respectively) (Table II). Fig 2 provides adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves accounting for these differences in baseline characteristics with respect to the same variables included in the Cox proportional hazard models based on the entire study population.

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate comparison of high-dose RIT-based vs conventional ASCT.

| Comparison | ASCT Conditioning | Treatment Failure | Overall Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Univariate | Control | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| RIT | 1.07 (0.69-1.64) | 0.77 | 1.08 (0.67-1.76) | 0.75 | |

| Multivariate | Control | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| RIT | 0.40 (0.23-0.69) | 0.001 | 0.49 (0.28-0.86) | 0.01 | |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; HR (95% CI), hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval; RIT, radioimmunotherapy.

Fig 2.

Adjusted outcomes for patients with mantle cell lymphoma following autologous stem cell transplantation with or without high-dose radioimmunotherapy-based conditioning. Progression-free (A) and overall survival (B) for all patients included in this analysis, depicted as Kaplan-Meier curves. The Control group acts as a reference while the radioimmunotherapy (RIT) group is adjusted via the important covariates (chemosensitivity, remission status at autologous stem cell transplantation [ASCT], ASCT in first remission, and age). These adjustments incorporate the important covariates along with the hazard ratio estimates. P-values are the results of Cox proportional hazard models. Tick marks represent censored events. Prob, probability.

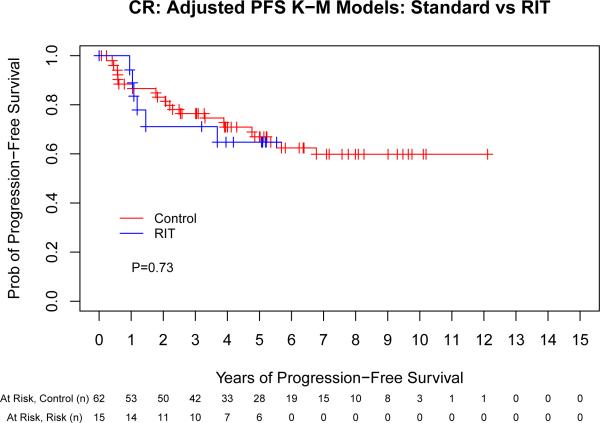

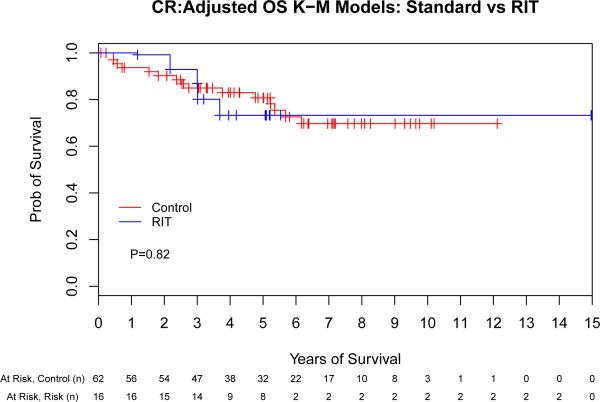

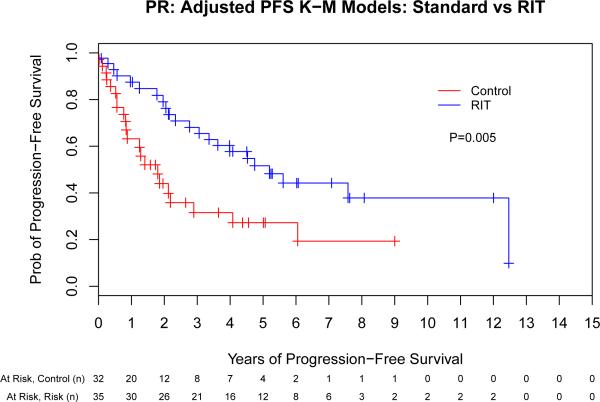

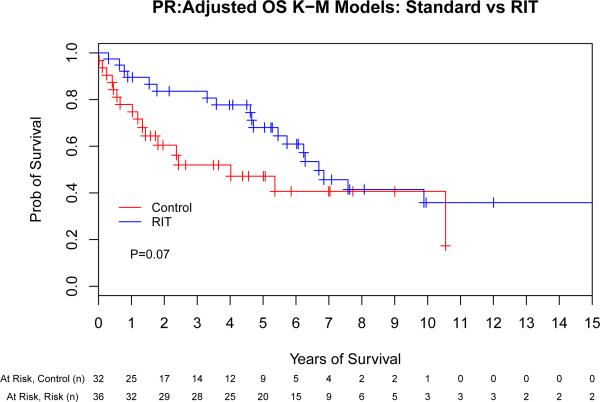

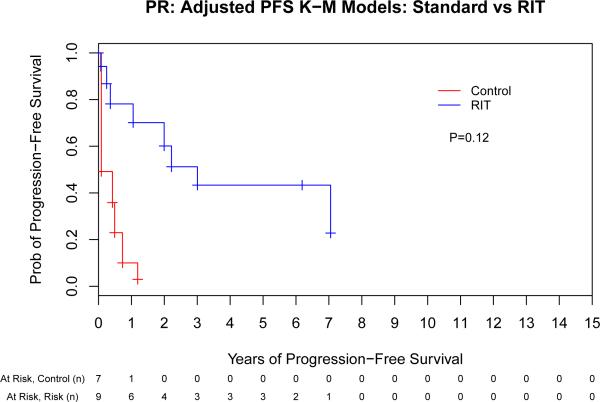

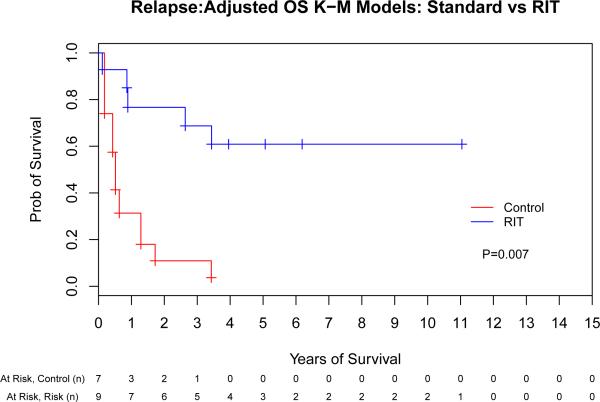

Impact of remission status

We next evaluated the impact of conditioning regimen by remission status to evaluate the hypothesis that the greatest benefit of high-dose RIT might be observed in those with the greatest disease burden. This assessment indicated that there was a potential interaction between remission status (CR vs PR vs stable/progressive disease [SD/PD]) and ASCT conditioning (PFS: p = 0.06, OS: p = 0.09) that warranted further investigation. Therefore, we performed a separate Cox proportional hazards model for each of the remission-status groups (CR, PR and SD/PD) for both PFS and OS (Fig 3). The same adjustment covariates (other than remission status at ASCT) were used from the previous analyses. This evaluation indicated that the magnitude of benefit of RIT-based conditioning increased as the pre-transplant disease status worsened, as detailed in Table III.

Fig 3.

The benefit of high-dose radioimmunotherapy increases as disease status worsens. Progression-free (A,C,E) and overall survival (B,D,F) for patients in complete remission (A,B), partial remission (C,D) or stable/progressive disease (E,F), depicted as Kaplan-Meier curves. The Control group acts as a reference while the radioimmunotherapy (RIT) group is adjusted via the important covariates. P-values are the results of Cox proportional hazard models. Tick marks represent censored events. Prob, probability.

Table III.

Multivariate comparison of high-dose RIT-based vs. conventional ASCT by remission status.

| Remission Status | ASCT Conditioning | Treatment Failure | Overall Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| CR | Control | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| RIT | 0.66 (0.23-1.86) | 0.43 | 1.14 (0.37-3.50) | 0.82 | |

| PR | Control | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| RIT | 0.36 (0.18-0.73) | 0.004 | 0.53 (0.26-1.08) | 0.07 | |

| SD/PD | Control | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| RIT | 0.14 (0.02-1.17) | 0.07 | 0.04 (0.004-0.41) | 0.007 | |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; HR (95% CI), hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease RIT, radioimmunotherapy.

Non-Relapse Mortality and Secondary Malignancies

Non-relapse deaths were comparable between RIT and non-RIT groups (7%: 4 events [7%] in the RIT group and 8 events [8%] in the control group). Multivariate regression analysis to detect significant differences was limited by the small number of events. Twenty total secondary malignancies were identified in 11% (n = 18) of patients in this study population with a median follow up 65 months from the time of ASCT to last contact or death. Of these 20 events, 6 were myeloid malignancies (i.e., myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukaemia). The remaining 14 events consisted of non-melanoma skin cancer (n = 9 [3 of which occurred in 1 patient]), non-small cell lung cancer (n = 1), pancreas cancer (n = 1), prostate cancer (n = 1), melanoma (n = 1) and ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast (n = 1). Within subgroups, 12% of patients in the control group suffered a secondary malignancy (n = 12), compared to 9.8% in the RIT group (n = 6). Myeloid malignancies occurred in 3.0% (n = 3; 2 with TBI and 1 with chemotherapy) of the control patients and 4.9% (n = 3) of the RIT patients. For the 3 RIT patients who developed a myeloid malignancy, the time of onset relative to ASCT was 5, 20 and 24 months (respectively), compared to 20, 49 and 66 months (respectively) for the 3 control patients. Formal adjusted comparisons for contributing factors, such as number of prior therapies, was not possible due to the limited number of events.

Discussion

Since its initial description 20 years ago, anti-CD20 RIT has been investigated in a variety of settings for the treatment of B-NHL. However, relatively little data exist regarding its use specifically for MCL. To our knowledge, this work represents the first direct comparison of RIT-based HDT vs conventional HDT for MCL. The previously published preliminary results of the first 16 patients with MCL who received RIT-based ASCT at our centre led us to evaluate a larger sample size with this approach (Gopal et al, 2002). Our current study specifically addresses the questions raised by this initial publication in the best approach short of a prospective randomized trial, which would not have been feasible at the time these studies began since they were among the first clinical trials of RIT-based HDT for MCL. Not surprisingly, patients who were referred for treatment with high-dose RIT tended to have MCL with more adverse features than their counterparts treated with conventional transplant strategies. Despite these differences, the unadjusted outcomes in the groups were similar. After adjusting for these significant covariates, the use of RIT in the conditioning regimen was associated with improvements in both PFS and OS following ASCT.

This method of adjustment is distinct from a matched cohort analysis, which identifies individuals in the RIT and control groups with similar baseline characteristics and compares their outcomes. However, considering the spectrum of differences between these groups (Table I), it would be challenging to find satisfactory matches between the groups in sufficient numbers to make any meaningful conclusions. By using the methods described here, we can account for these differences through regression modelling, which allows us to consider all patients. With a matched cohort approach, some patients in the control group would be excluded from our analysis.

Since TBI-based HDT was shown to be superior in a randomized study by the European MCL Network (Dreyling et al, 2005), ASCT has been considered a standard treatment option for a large proportion of patients with MCL. That said, nearly all patients will eventually relapse, with the shortest remission durations observed for those not in CR prior to transplant (Geisler et al, 2008). These data would suggest that patients not in CR also experience the most potential benefit from a high-dose RIT-based conditioning regimen. This observation may be explained by the potential for increased crossfire amplification of absorbed dose to haematolymphoid sites in patients with persistent disease, or by providing an alternative therapeutic approach to sites of persistent and thus relatively chemorefractory disease, either of which could lead to better outcomes than conventionally treated patients. This finding also corroborates similar data that we have recently reported using standard-dose yttrium-90 (90Y)-ibritumomab tiuxetan prior to non-myeloablative allogeneic transplantation for patients with persistent indolent B-NHL and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (Cassaday et al, 2015). However, our findings appear to conflict with the Nordic MCL3 study, where late intensification of first incomplete remission with standard-dose 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan did not appear to improve results following ASCT compared to historical controls (Kolstad et al, 2014). These disparate findings may be due to our inclusion of patients with relapsed or non-responding disease, but is probably best explained by the use of intensified doses of RIT, which may be more effective than standard doses in patients with relatively chemoresistant lymphoma.

In view of the similar incidence of non-relapse mortality in either arm, our data would suggest that the benefits of the RIT-based approach were from improved disease control and not from less treatment-related mortality than with conventional ASCT. Likewise, secondary malignancies (particularly myeloid malignancies), one of the more concerning long-term complications following ASCT, did not appear to be higher than in the non-randomized control group, as has been previously described (Gopal et al, 2003; Lenz et al, 2004; Guidetti et al, 2011). This point is highlighted by the long, prospective follow up in the RIT arm with study-mandated annual bone marrow evaluations to detect early signs of relapse or secondary myeloid disorders, which should lead to an relative overestimation of events compared to the control group.

As with any long-term comparison, our data are not able to address the specific impact of this approach in the current era of effective newer agents, such as bendamustine, lenalidomide and ibrutinib (Goy et al, 2013; Rummel et al, 2013; Wang et al, 2013). Nevertheless, none of the recently introduced therapies are thought to be curative, and improved methods to extend disease control and survival are critical for MCL. While the withdrawal of 131I-tositumomab from the U.S. market in 2014 limits the ability to carry forward this specific strategy, our data demonstrate a “proof of principle” that can be potentially extrapolated to 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan, which is available for future investigation of these strategies, or to other radioimmunoconjugates in development. At this time, we also do not yet have data on the impact of rituximab maintenance in this setting (Le Gouill et al, 2014), though these efforts are forthcoming.

In conclusion, this analysis indicates that the use of high-dose anti-CD20 RIT in the conditioning regimen for ASCT in MCL is associated with superior PFS and OS relative to conventional HDT in patients with persistent or refractory disease. Until an approach is identified that provides long-term remissions with minimal toxicity for the vast majority of patients, ASCT will probably remain a critical option for patients with MCL. These data suggest that the use of intensified targeted radiation-based conditioning regimens could be evaluated in a disease- and response-adapted strategy with the hope to deliver improved outcomes for those patients with the most adverse prognoses.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K12 CA076930 [R.D.C.], P01 CA044991 [O.W.P.], and K24 CA184039 [A.K.G.]) and the Lymphoma Research Foundation Mantle Cell Lymphoma Research Initiative. Support was also provided by Hutchinson Center/University of Washington Cancer Consortium Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA015704) and philanthropic gifts from Frank and Betty Vandermeer, Don and Debbie Hunkins, the Mary Aileen Wright Memorial Fund and the David and Patricia Giuliani Family Foundation. A.K.G. is a Scholar in Clinical Research for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Authorship Statement

RDC designed research; collected, analysed and interepreted data, and wrote the manuscript. PAS and TAG performed statistical analysis, analysed and interpreted data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. TRC, JMP, JR, ELB, BGT, MP, JJO, WIB, LAH, ARS, DJG, SDS, ENL, DGM and OWP interpreted data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. AKG designed research, analysed and interpreted data, reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosure

RDC: Research Funding: Seattle Genetics, Pfizer. AKG: Honoraria: Seattle Genetics, Pfizer, Takeda/MPI; Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline, Spectrum, Seattle Genetics, Merck, Teva, Jannsen, Gilead, Takeda. The remaining authors declare no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Cassaday RD, Guthrie KA, Budde EL, Thompson L, Till BG, Press OW, Chauncey TR, Pagel JM, Petersdorf SH, Palanca-Wessels MC, Philip M, Bensinger WI, Holmberg LA, Shustov A, Green DJ, Libby EN, Maloney DG, Gopal AK. Specific features identify patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma benefitting from autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2013;19:1403–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassaday RD, Storer BE, Sorror ML, Sandmaier BM, Guthrie KA, Maloney DG, Rajendran JG, Pagel JM, Flowers ME, Green DJ, Rezvani AR, Storb RF, Press OW, Gopal AK. Long-term outcomes of patients with persistent indolent B cell malignancies undergoing nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015;21:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Fisher RI, Hagenbeek A, Zucca E, Rosen ST, Stroobants S, Lister TA, Hoppe RT, Dreyling M, Tobinai K, Vose JM, Connors JM, Federico M, Diehl V. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney JP, Stiff PJ, Toor AA, Parthasarathy M. BEAM allogeneic transplantation for patients with Hodgkin's disease who relapse after autologous transplantation is safe and effective. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2003;9:177–182. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon LE, Johnson JL, Niedzwiecki D, Cheson BD, Hurd DD, Bartlett NL, Lacasce AS, Blum KA, Byrd JC, Kelly M, Stock W, Linker CA, Canellos GP. Immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for untreated patients with mantle-cell lymphoma: CALGB 59909. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:6101–6108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delarue R, Haioun C, Ribrag V, Brice P, Delmer A, Tilly H, Salles G, Van Hoof A, Casasnovas O, Brousse N, Lefrere F, Hermine O, Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de lA CHOP and DHAP plus rituximab followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: a phase 2 study from the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 2013;121:48–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-370320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devizzi L, Guidetti A, Tarella C, Magni M, Matteucci P, Seregni E, Chiesa C, Bombardieri E, Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Gianni AM. High-dose yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan with tandem stem-cell reinfusion: an outpatient preparative regimen for autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:5175–5182. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyling M, Hiddemann W. Current treatment standards and emerging strategies in mantle cell lymphoma. Hematology / the Education Program of the American Society of Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2009:542–551. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyling M, Lenz G, Hoster E, Van Hoof A, Gisselbrecht C, Schmits R, Metzner B, Truemper L, Reiser M, Steinhauer H, Boiron JM, Boogaerts MA, Aldaoud A, Silingardi V, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hasford J, Parwaresch R, Unterhalt M, Hiddemann W. Early consolidation by myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission significantly prolongs progression-free survival in mantle-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the European MCL Network. Blood. 2005;105:2677–2684. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenske TS, Zhang MJ, Carreras J, Ayala E, Burns LJ, Cashen A, Costa LJ, Freytes CO, Gale RP, Hamadani M, Holmberg LA, Inwards DJ, Lazarus HM, Maziarz RT, Munker R, Perales MA, Rizzieri DA, Schouten HC, Smith SM, Waller EK, Wirk BM, Laport GG, Maloney DG, Montoto S, Hari PN. Autologous or reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chemotherapy-sensitive mantle-cell lymphoma: analysis of transplantation timing and modality. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:273–281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci PF, Vanazzi A, Grana CM, Cremonesi M, Bartolomei M, Chinol M, Ferrari M, Radice D, Papi S, Martinelli G, Paganelli G. High activity 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) with peripheral blood progenitor cells support in patients with refractory/resistant B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. British journal of haematology. 2007;139:590–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, Andersen NS, Pedersen LB, Jerkeman M, Eriksson M, Nordstrom M, Kimby E, Boesen AM, Kuittinen O, Lauritzsen GF, Nilsson-Ehle H, Ralfkiaer E, Akerman M, Ehinger M, Sundstrom C, Langholm R, Delabie J, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Brown P, Elonen E. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo-purged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2008;112:2687–2693. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal AK, Rajendran JG, Petersdorf SH, Maloney DG, Eary JF, Wood BL, Gooley TA, Bush SA, Durack LD, Martin PJ, Matthews DC, Appelbaum FR, Bernstein ID, Press OW. High-dose chemo-radioimmunotherapy with autologous stem cell support for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2002;99:3158–3162. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal AK, Gooley TA, Maloney DG, Petersdorf SH, Eary JF, Rajendran JG, Bush SA, Durack LD, Golden J, Martin PJ, Matthews DC, Appelbaum FR, Bernstein ID, Press OW. High-dose radioimmunotherapy versus conventional high-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsed follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a multivariable cohort analysis. Blood. 2003;102:2351–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal AK, Rajendran JG, Gooley TA, Pagel JM, Fisher DR, Petersdorf SH, Maloney DG, Eary JF, Appelbaum FR, Press OW. High-dose [131I]tositumomab (anti-CD20) radioimmunotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for adults > or = 60 years old with relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:1396–1402. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal AK, Gooley TA, Rajendran JG, Pagel JM, Fisher DR, Maloney DG, Appelbaum FR, Cassaday RD, Shields A, Press OW. Myeloablative I-131-tositumomab with escalating doses of fludarabine and autologous hematopoietic transplantation for adults age >/= 60 years with B cell lymphoma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20:770–775. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, Kalayoglu Besisik S, Drach J, Ramchandren R, Zhang L, Cicero S, Fu T, Witzig TE. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:3688–3695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti A, Carlo-Stella C, Ruella M, Miceli R, Devizzi L, Locatelli SL, Giacomini A, Testi A, Buttiglieri S, Risso A, Mariani L, Di Nicola M, Passera R, Tarella C, Gianni AM. Myeloablative doses of yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan and the risk of secondary myelodysplasia/acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer. 2011;117:5074–5084. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Delgado F, Holmberg L, Hooper H, Petersdorf S, Press O, Maziarz R, Maloney D, Chauncey T, Appelbaum F, Bensinger W. Autologous stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin's disease: busulfan, melphalan and thiotepa compared to a radiation-based regimen. Bone marrow transplantation. 2003;32:279–285. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, Gisselbrecht C, van Hoof A, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Pfreundschuh M, Reiser M, Metzner B, Einsele H, Peter N, Jung W, Wormann B, Ludwig WD, Duhrsen U, Eimermacher H, Wandt H, Hasford J, Hiddemann W, Unterhalt M. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:558–565. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolstad A, Laurell A, Jerkeman M, Gronbaek K, Elonen E, Raty R, Pedersen LB, Loft A, Bogsrud TV, Kimby E, Hansen PB, Fagerli UM, Nilsson-Ehle H, Lauritzsen GF, Lehmann AK, Sundstrom C, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Ralfkiaer E, Ehinger M, Delabie J, Bentzen H, Schildt J, Kostova-Aherdan K, Frederiksen H, Brown Pde N, Geisler CH, Nordic Lymphoma G. Nordic MCL3 study: 90Y-ibritumomab-tiuxetan added to BEAM/C in non-CR patients before transplant in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123:2953–2959. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-541953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Nademanee A, Fung HC, Raubitschek AA, Molina A, Yamauchi D, Rodriguez R, Spielberger RT, Falk P, Palmer JM, Forman SJ. Phase II trial of a transplantation regimen of yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan and high-dose chemotherapy in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:90–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gouill S, Callanan M, Macintyre E, delfau-Larue MH, bodet-Milin C, Meignan M, Moreau A, Travers-Glehen A, Bene MC, Haouin C, Gressin R, Casasnovas RO, Ribrag V, Damaj G, Gyan E, Oberic L, Bouabdallah K, Thieblemont C, Hermine O. Clinical, Metabolic and Molecular Responses After 4 Courses of R-DHAP and After Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Untreated Mantle Cell Lymphoma Patients Included in the LyMa Trial, a Lysa Study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting abstracts) 2012;120:152. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, Bouabdallah K, Gyan E, Damaj G, Ribrag V, Bologna S, Gressin R, Casasnovas O, Haioun C, Solal-Celigny P, Maisonneuve H, Van Den Neste E, Moreau A, Bene MC, Salles G, Tilly H, Lamy T, Hermine O. Rituximab Maintenance Versus Wait and Watch after Four Courses of R-DHAP Followed By Autologous Stem Cell transplantation in Previously Untreated Young Patients with Mantle Cell Lymphoma: First Interim Analysis of the Phase III Prospective Lyma Trial, a Lysa Study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting abstracts) 2014;124:146. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz G, Dreyling M, Schiegnitz E, Haferlach T, Hasford J, Unterhalt M, Hiddemann W. Moderate increase of secondary hematologic malignancies after myeloablative radiochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with indolent lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:4926–4933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nademanee A, Forman S, Molina A, Fung H, Smith D, Dagis A, Kwok C, Yamauchi D, Anderson AL, Falk P, Krishnan A, Kirschbaum M, Kogut N, Nakamura R, O'Donnell M, Parker P, Popplewell L, Pullarkat V, Rodriguez R, Sahebi F, Smith E, Snyder D, Stein A, Spielberger R, Zain J, White C, Raubitschek A. A phase 1/2 trial of high-dose yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan in combination with high-dose etoposide and cyclophosphamide followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with poor-risk or relapsed non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2005;106:2896–2902. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press OW, Eary JF, Appelbaum FR, Martin PJ, Badger CC, Nelp WB, Glenn S, Butchko G, Fisher D, Porter B, Matthews DC, Fisher LD, Bernstein ID. Radiolabeled-antibody therapy of B-cell lymphoma with autologous bone marrow support. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1219–1224. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310213291702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press OW, Eary JF, Gooley T, Gopal AK, Liu S, Rajendran JG, Maloney DG, Petersdorf S, Bush SA, Durack LD, Martin PJ, Fisher DR, Wood B, Borrow JW, Porter B, Smith JP, Matthews DC, Appelbaum FR, Bernstein ID. A phase I/II trial of iodine-131-tositumomab (anti-CD20), etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2000;96:2934–2942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, Banat GA, von Grunhagen U, Losem C, Kofahl-Krause D, Heil G, Welslau M, Balser C, Kaiser U, Weidmann E, Durk H, Ballo H, Stauch M, Roller F, Barth J, Hoelzer D, Hinke A, Brugger W, Study group indolent L. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1203–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni A, Avivi I, Rowe JM, Yeshurun M, Levi I, Or R, Patachenko P, Avigdor A, Zwas T, Nagler A. A randomized study comparing yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) and high-dose BEAM chemotherapy versus BEAM alone as the conditioning regimen before autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with aggressive lymphoma. Cancer. 2012;118:4706–4714. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MR, Li H, Gordon L, Gascoyne RD, Paietta E, Forero-Torres A, Kahl BS, Advani R, Hong F, Horning SJ. Phase II study of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone immunochemotherapy followed by yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan in untreated mantle-cell lymphoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E1499. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:3119–3126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storer BE, Gooley TA, Jones MP. Adjusted estimates for time-to-event endpoints. Lifetime data analysis. 2008;14:484–495. doi: 10.1007/s10985-008-9098-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vose JM, Carter S, Burns LJ, Ayala E, Press OW, Moskowitz CH, Stadtmauer EA, Mineshi S, Ambinder R, Fenske T, Horowitz M, Fisher R, Tomblyn M. Phase III randomized study of rituximab/carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM) compared with iodine-131 tositumomab/BEAM with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the BMT CTN 0401 trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:1662–1668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Oki Y, Pro B, Romaguera JE, Rodriguez MA, Samaniego F, McLaughlin P, Hagemeister F, Neelapu S, Copeland A, Samuels BI, Loyer EM, Ji Y, Younes A. Phase II study of yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:5213–5218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, Goy A, Auer R, Kahl BS, Jurczak W, Advani RH, Romaguera JE, Williams ME, Barrientos JC, Chmielowska E, Radford J, Stilgenbauer S, Dreyling M, Jedrzejczak WW, Johnson P, Spurgeon SE, Li L, Zhang L, Newberry K, Ou Z, Cheng N, Fang B, McGreivy J, Clow F, Buggy JJ, Chang BY, Beaupre DM, Kunkel LA, Blum KA. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:507–516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter JN, Inwards DJ, Spies S, Wiseman G, Patton D, Erwin W, Rademaker AW, Weitner BB, Williams SF, Tallman MS, Micallef I, Mehta J, Singhal S, Evens AM, Zimmer M, Molina A, White CA, Gordon LI. Yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan doses calculated to deliver up to 15 Gy to critical organs may be safely combined with high-dose BEAM and autologous transplantation in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:1653–1659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelenetz AD, Noy A, Pandit-Taskar N, Scordo M, Rijo I, Zhou Y, O'Donoghue JA, Divgi D. Sequential radioimmunotherapy with tositumomab/Iodine I131 tositumomab followed by CHOP for mantle cell lymphoma demonstrates RIT can induce molecular remissions. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24 Abstract 7560. [Google Scholar]