Abstract

We study the problem of testing for single marker–multiple phenotype associations based on genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics without access to individual-level genotype and phenotype data. For most published GWASs, since obtaining summary data is substantially easier than accessing individual-level phenotype and genotype data, while often multiple correlated traits have been collected, the problem studied here has become increasingly important. We propose a powerful adaptive test and compare its performance with some existing tests. We illustrate its applications to analyses of a meta-analysed GWAS dataset with three blood lipid traits and another with sex-stratified anthropometric traits, and further demonstrate its potential power gain over some existing methods through realistic simulation studies. We start from the situation with only one set of (possibly meta-analyzed) genome-wide summary statistics, then extend the method to meta analysis of multiple sets of genome-wide summary statistics, each from one GWAS. We expect the proposed test to be useful in practice as more powerful than or complementary to existing methods.

1 Introduction

Almost every genome-wide association study (GWAS) has been analyzed on univariate phenotypes even when multiple correlated phenotypes are available on each individual. Since most associated common variants have only small effect sizes, e.g. with odds ratios often in the range of 1.1–1.3, to boost power, meta analysis of multiple GWAS data sets have become more important and more popular. On the other hand, there is evidence showing that jointly testing multiple correlated traits may increase the statistical power and thus chance of detecting associated genetic variants, most often single nucleiotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (e.g. Bolormaa et al., 2014)), as supported by many empirical studies (e.g. Galesloot et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). Furthermore, multivariate trait analysis may shed light on pleiotropic effects (Chung et al., 2014). Accordingly, many methods have been proposed to study single SNP–multiple trait associations (e.g., Klei et al., 2008; Ferreira and Purcell, 2009; Yang et al., 2010; Stephens, 2013; van der Sluis et al., 2013; He et al., 2013). A natural approach is to linearly combine the univariate analysis results for single traits (Yang et al., 2010). An extreme in this class is to use only the minimum p-value, called minP test that takes the most significant SNP-trait association while effectively ignoring other associations. Another extreme is to give an equal weight to each single trait association, which is expected to be more powerful under the so-called effect homogeneity when each of the univariate traits is equally associated to the SNP (He et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015). Another class of methods are based on the intuitive idea of dimension reduction: the multivariate traits are summarized into a univariate score, which is then subject to traditional univariate association testing. Commonly used dimension reduction methods include principal component analysis (PCA) (Wang and Abbott, 2008; Lan et al., 2003) and principal components of heritability (PCH) (Klei et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2012). A few top PCs are constructed to preserve multivariate trait variations, which however may not be able to capture sufficient association signals (Aschard et al., 2014). Even if the top few PCs can capture a large fraction of the phenotypic variation, we still have to treat the top PCs as a multivariate trait (unless only one PC is used), which is the subject here. Related to dimension reduction, canonical correlation analysis (CCA) (Ferreira and Purcell, 2009) finds a linear combination of multivariate traits that has the largest correlation with the genetic variant, which turns out to be equivalent to MANOVA. More recent methods include combining univariate p-values using an extended Simes procedure as implemented in TATES (van der Sluis et al 2013), regressing genotypes on phenotypes as in MultiPhen (O’Reilly et al., 2012; Wang, 2014), kernel machine regression (KMR) (Maity et al., 2012), and multivariate functional linear models (Wang et al., 2015). As pointed out by He et al. (2013), TATES is similar to the minP test. More generally, Zhang et al. (2014) proposed a class of so-called sum of powered score (SPU) tests in the framework of generalized estimating equations (GEEs). The class of the SPU tests, say SPU(γ) indexed by a positive integer γ, cover some existing tests as special cases: for example, SPU(1) is a burden test in analysis of rare variants and behaves like the tests for effect homogeneity (He et al., 2013) in the current context as studied by Zhu et al. (2015); SPU(2) is equivalent to the KMR (with a linear kernel) in GEE (Wang et al., 2013,b); and SPU(∞) is similar to the minP test. In some situations, an SPU(γ) test with 2 < γ < ∞ is more powerful than the above three special cases as shown in other contexts (e.g. Pan et al., 2015). To simplify the use as an overall test (e.g. to avoid the issue of multiple testing), rather than looking at the results of the individual SPU tests, they proposed an adaptive SPU (aSPU) test to combine information across multiple SPU(γ) tests with a range of γ values. They also investigated the Score test in GEE, denoted as GEE-Score test; it was pointed out that, with quantitative traits, the GEE-Score test is equivalent to CCA and MANOVA. The GEE-Score test is also essentially equivalent to the Score-based Chi-squared test proposed by He et al. (2013). Between the GEE-Score and GEE-aSPU tests, they are complementary to each other with one more powerful than the other in some, but not all, situations. The GEE-based tests are general, applicable to both quantitative and binary/count traits, while many other methods like PCA, PCH, CCA and MANOVA are only suitable for quantitative traits.

Most existing methods require the use of individual-level genotype and phenotype data; among the above mentioned methods, the only exceptions are TATES and two tests of Zhu et al. (2015). When only GWAS summary Z-scores are available, Stephens (2013) proposed a Bayesian approach by partitioning traits into three categories: directly associated, indirectly associated, and unassociated. The posterior probabilities of these partitions give direct inference of multi-trait associations. Very recently Zhu et al. (2015) proposed two tests for meta-analysis of multiple correlated traits across multiple studies using only GWAS summary statistics; we will study their connections to and differences from our proposed test later. As a simple alternative, one can also combine the univariate single-trait analyses through a Chi-squared test, which is similar to the GEE-Score test applied to individual-level genotype and phenotype data. In this paper, we extend the GEE-aSPU test to the current context with only summary Z-statistics for univariate traits (i.e. no individual-level genotype and phenotype data), and compare its performance with that of the Chi-squared test. We also study the minP test that selects the most significant SNP–single trait association as its test statistic; it is expected to be powerful when the SNP is associated with one or few traits with a large effect size, but not otherwise. As in the context with individual-level genotype and phenotype data, we found that the proposed aSPU test and the other two standard tests are complementary to each other: one of them was more powerful than the other two in some, but not all, situations. Our proposed aSPU test and the two standard tests can be also directly applied to multiple sets of summary statistics drawn from multiple GWAS cohorts. We conducted simulation studies similar to Zhu et al. (2015), again demonstrating the promising performance of the aSPU test. Hence, we recommend our proposed aSPU test as a useful alternative to the existing tests.

2 Methods

2.1 Notation and two existing methods

Consider a GWAS with n unrelated individuals and we want to test the genetic association of one single SNP with K related quantitative traits while adjusting for a set of p covariates. Denote the outcomes as Yk = (y1k, …, ynk)T, k = 1, …, K, covariate Xi = (xi1, …, xip)T, and genotype gi as the number of minor alleles, i = 1, …, n, Let , and G = (g1, …, gn)T.

Using a linear regression model for Yk, we have

| (1) |

where γk is of length p, εk is of length n and assumed to independently follow the normal distribution with variance . Denote the correlation ρkl = corr(yik, yil), k, l = 1, …, K.

Denote Ge as the residual vector of regressing G on X. We then have and can construct a corresponding Z-score Zk = β̂k/se(β̂k) for testing the genetic association of the k-th trait on null hypothesis H0,k: βk = 0. Here . Therefore we have

and

Hence we have corr(β̂k, β̂j) = ρkj. Ignoring the variation due to se(β̂k)’s, we have corr(Zk, Zj) ≈ ρkj = corr(yik, yil). This method of estimating the correlation matrix based on summary statistics has also been considered recently by other authors (Stephens, 2013; Zhu et al., 2015).

In summary, the correlations of the Z-scores reflect those of the quantitative traits, and are independent of covariates including the genotype. With only summary data, they can be empirically estimated from the Z-scores across null SNPs based on their sample correlation matrix R̂ as an estimate of R = (ρkj). Hence, for any given SNP, its Z-statistic vector Z = (Z1, …, ZK)T across the multiple traits approximately follows a multivariate normal distribution N(0, R), based on which we can test the null hypothesis H0: β1 = … = βK = 0.

Given the Z-scores Z = (Z1, …, ZK)T and the estimated correlation matrix R̂, there are two standard methods to combine the information across the multiple Z-scores. The first is the so-called (univariate) minimum p-value (minP) that selects the most significant Z-score, or equivalently, the minimum p-value of the univariate single-trait tests with a test statistic

Based on that the joint distribution of Z = (Z1, …, ZK) is (asymptotically) multivariate normal MVN(0, R) with mean 0 and covariance matrix R under H0, one can calculate its p-value by simulations as to be introduced later. Alternatively, one can use numerical integration to do so (Conneely and Boehnke, 2007):

where f(x1, …, xK; μ, R) is the density function for MVN(μ, R). We note that the minP test is similar to TATES as demonstrated in Zhang et al (2014) in the context with individual-level SNP and phenotype data; the above proposed minP test adjusts multiple testing (asymptotically) exactly while TATES uses an approximate method based on an extended Simes procedure for multiple testing.

In contrast to using only the most significant univariate Z-score across the multiple traits, the other standard method is the Chi-squared test that utilizes the multivariate Z-scores to construct its statistic

which follows an asymptotic chi-squared distribution with K degrees of freedom (DF) under the null hypothesis. We can easily compute its p-value as 1 − FK(χ2), where FK() is the cumulative distribution function of a random variate. It is noted that, in the presence of individual-level genotype and phenotype data, the above Chi-squared test is similar to the MANOVA/CCA, MultiPhen, the score-based Chi-squared test of He et al. (2013), and the GEE-Score test, though the latter ones cannot be directly applied to summary statistics.

2.2 New methods

The above two standard methods use either only one or all the Z-scores, each based on a univariate test on a single trait. In practice, especially for the case with a large K, some traits may not be associated with the SNP, hence we may want to weight the Z-scores accordingly: we would like to give a higher weight to a larger Z-score because its corresponding trait is more likely to be associated with the SNP. However, how much to over-weight a likely associated SNP depends on the true association pattern, which is unknown. The main idea of the aSPU test is to try various weights indexed by a non-negative integer γ, then choose the one giving the most significant p-value (Pan et al 2014; Zhang et al 2014). The original aSPU test was proposed to test for single trait–multiple SNP, or multiple trait–single SNP, associations in the presence of individual-level SNP and phenotype data. Here we adapt it to the current context of multiple trait–single SNP association with only summary statistics. Specifically, first, we use S = S(Z) = (S1, …, SK)′ as a vector of summary statistics based on Z-statistics; by default we will simply use S = Z, but another option S = R̂−1Z is possible as to be discussed later. Denote Σ = Cov(S|H0) = R̂ or R̂−1, depending on whether S = Z or S = R̂−1Z. Then we construct a SPU test with its test statistic as the sum of powered summary statistics:

where Sk is the kth component of the summary statistics S, and 0 < γ < ∞ is a positive integer. As an even integer γ → ∞,

Following the previous applications of the aSPU test, we construct multiple SPU(γ) tests with γ ∈ Γ = {1, 2, …, 8, ∞}. As discussed in Zhang et al (2014), the SPU(1) test corresponds to the Sum or Average test used by Shen et al (2010), and is also the same as the tests for effect homogeneity proposed by (He et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015) if S = R̂−1Z; the SPU(2) test is the same as the sum of squared score (SSU) test (Yang and Wang 2012), which was originally proposed in Pan (2009) for single trait-multiple SNP association testing and is closely related to kernel machine regression (Wu et al 2010) and its extension to GEE (Wang et al., 2013b); finally, it is obvious that the SPU(∞) statistic is the same as the minP test. Depending on the unknown true genetic association patterns, one or few of the SPU tests will be more powerful than others, as discussed in Zhang et al. (2014). In particular, using a larger γ corresponds to over-weight those larger |Sk|’s because the SPU(γ) statistic can be regarded as a weighted sum of score statistic with weights . This weighting scheme has a similar effect on selecting more significant Sk’s, as implemented through thresholding in Zhu et al. (2015), also shown by Pan et al. (2015) in a different context; however, we do notice one difference: here we used powered Sk’s, not thresholding on |Sk|’s as proposed by Zhu et al. (2015), partly because the latter cannot reduce to the burden tests. Depending on the unknown true association patterns, some SPU tests might be more powerful. For example, if all the traits are associated with the SNP with similar effect sizes in the same direction, then SPU(1) is expected to be most powerful; on the other hand, if their association directions are different (and/or some are not associated at all), then SPU(2) is often more powerful; finally, if there is only one or few traits are associated with a large effect size, then SPU(∞) (or uminP) will be most powerful. Hence, to construct a powerful test, we adaptively select one of the SPU tests to form the aSPU test as the following:

where pγ is the p-value of SPU(γ) test.

Except for γ = 1, 2 or ∞, it is difficult to derive an analytical form of the null distribution of SPU(γ), thus its p-value. Hence, Monte Carlo simulations are used to approximate its null distribution. Specifically we generate null summary statistics Tb = (Tb1, …, TbK)′ ~ MVN(0, Σ) independently for b = 1, …, B, and calculate . Then the significance p-value of SPU(γ) is

Note that pγ is also a simulation-based p-value for the minP test, as an alternative to the numerical integration-based one introduced earlier. Since all SNPs have the same covariance matrix R under the null hypothesis, we just need to simulate one set of Monte Carlo samples and efficiently compute significance values for all SNPs simultaneously.

For the adaptive aSPU test, we can also efficiently compute its significance p-value based on the same set of the Monte Carlo samples being used for the SPU tests as following. Note that for each SPU(γ)b itself, we can compute its p-value based on its rank

Denote its minimum as . Then we can compute the significance of aSPU as

Note that, since the null distributions of the Z-statistics, thus of the test statistics, do not depend on the SNP being tested, the above procedure to generate an empirical null distribution of a test statistic needs to be done only once. In addition, since each Z-statistic Zk can be regarded as a univariate or marginal score test statistic after being normalized by its variance, strictly speaking, the above proposed SPU and aSPU tests should be called inverse variance weighted SPU (SPUw) and aSPU (aSPUw) tests (Kim et al., 2014); due to their similar performance in many situations, for simplicity, we do not distinguish them.

The motivation behind the choice between S = Z and S = R̂−1Z is the following. To avoid complex notation, we assume that Zk = β̂k/se(β̂k) and se(β̂1) = … = se(β̂K). If the marginal association effects are equal with β1 = … = βK in the marginal models (1), then the SPU(1) test with S = R̂−1Z is most powerful (O’Brien, 1984), which is the same as the tests for effect homogeneity (He et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015); on the other hand, consider the joint association between the multivariate trait and the SNP (Zhang et al., 2014), if the joint association effects are equal with , then the SPU(1) test with S = Z will be most powerful (Pan, 2009). Hence, the choice between S = Z and S = R̂−1Z depends on which situation is true, which however is unknown. Furthermore, it also depends on assumptions on the equality of the variances fo some related quantities (He et al., 2013), which are unknown either. Based on our experience with limited simulations (to be shown), we conclude that using S = Z seems to be more stable and often more powerful, though the other one could be more powerful in some situations, we recommend the use of S = Z. In the following, by default we always used S = Z for the SPU and aSPU tests unless specified otherwise.

2.3 Extension to meta analysis

We briefly note that our proposed aSPU test can be directly applied to meta analysis of multiple sets of summary summary statistics for single or multiple traits, where each set is drawn from one of several GWASs with possibly different traits and overlapping subjects (Zhu et al., 2015). Specifically, if Zjk is the Z-statistic for trait k in study j, then we have Z = (Z11, ‥, Z1K, Z21, …, ZJK)′. If the study sample sizes nj’s vary widely, one may want to weight the studies different by scaling each Zjk by a factor of ; in this paper, for simplicity we do not consider such weighting. First, we can use Z’s of the estimated null SNPs in the genome to estimate the correlation matrix of Z as R̂ as before, which may also take account of correlations among the multiple studies due to overlapping study subjects (or cryptic relatedness) (Lin and Sullivan, 2009). Next, for any given SNP to be tested, we construct a vector of summary statistics as S = Z or S = R̂−1Z, and apply the SPU and aSPU tests discussed before.

Zhu et al. (2015) proposed two tests, THom for a homogeneous effect and THet for heterogeneous effects, which are related to our proposed tests with the use of S = R̂−1Z (if we ignore weighting on individual studies with ). First, as mentioned before, their test for homogeneity THom is the same as our SPU(1) test. Second, to account for possibly different association strengths and directions of Sjk’s, their THet uses thresholding to select various sets of larger components of |S|, then constructs a homogeneity test like SPU(1) based on each of the selected subsets, and finally select the largest homogeneity test statistic as its final result; in comparison, we use a power index γ in multiple SPU(γ) tests to over-weight different sets of larger components of S, then choose the most significant SPU(γ) test as the final result. Pan et al. (2015) compared the two schemes, thresholding versus weighting, in a different context, and the latter seemed to be more effective if the effect size was weak. Both methods use simulations to estimate the null distributions and thus p-values. We will use simulated data to compare their performance.

3 Results

3.1 Application to a meta-analyzed lipid GWAS dataset

We applied the methods to a meta-analyzed GWAS dataset by the Global Lipids Consortium (Teslovich et al., 2010). The original study meta analyzed 46 genome-wide studies on lipids with a total of more than 100,000 individuals of European ancestry. Around 2.6 million directly genotyped or imputed SNPs were tested for association with each of the four lipid traits: total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) and triglycerides (TG). For each SNP and each trait, evidence of association was combined across the 46 studies using a Z-statistic based on a fixed-effect meta-analysis model. There were 95 loci that showed associations at the genome-wide significance level (p-value < 5 × 10−8) with at least one of the four traits tested. For the current study, the raw genotype and phenotype data are not available; the univariate summary Z-scores for each SNP-single trait associations were downloaded from http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/public/lipids2010. Since the four lipid traits are linearly dependent, a Chi-squared test conducted on any of the three traits is the same as that on all four traits, though other tests, including the minP and aSPU tests, may give different results for different sets of the traits; to facilitate comparisons with the Chi-squared test, in the following, we only analyzed three traits, TG, HDL and LDL. Our goal was to identify those SNPs associated with at least one of the three traits.

We first consider univariate analyses. There were in total 5396 SNPs that passed the genome-wide significance level (p-value < 5 × 10−8) for at least one of the four traits. For individual trait analysis, there were 2593, 1808, 2214 and 1769 significant SNPs for TC, TG, HDL and LDL respectively. Note that the above univariate analyses did not correct multiple testing on the four traits.

Now we consider multi-trait analyses for TG, HDL and LDL. First, we filtered out those SNPs with at least one missing Z-score, leading to a total of 2,691,464 SNPs with non-missing summary Z-scores for all three traits. We used B = 109 Monte Carlo simulations to estimate the p-values for the SPU and aSPU tests.

We estimated the correlation matrix of the three traits based on the Z-scores of the (estimated) null SNPs (after excluding those genome-wide significant SNPs for at least one trait, i.e., at least a univariate p-value < 5 × 10−8). Although we could potentially use only those (nearly) independent SNPs, we did not feel it would be critical and thus did not pursue it.

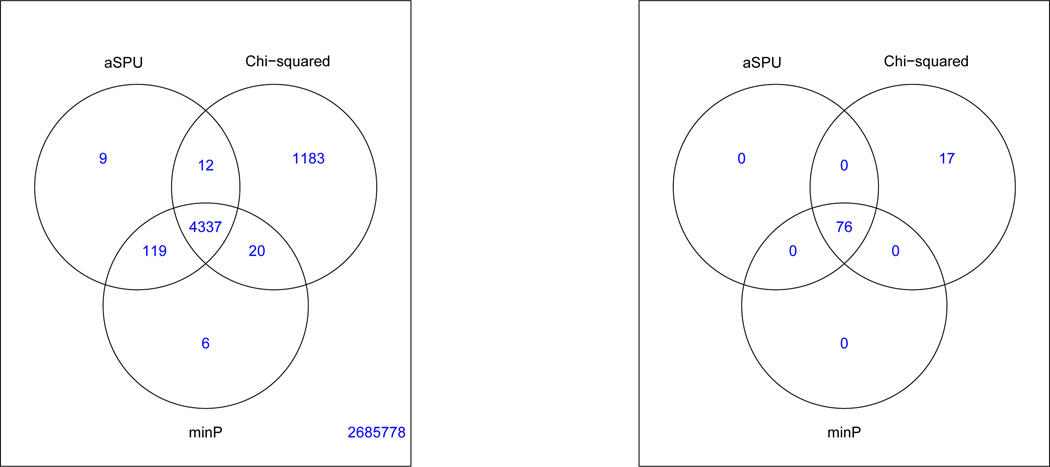

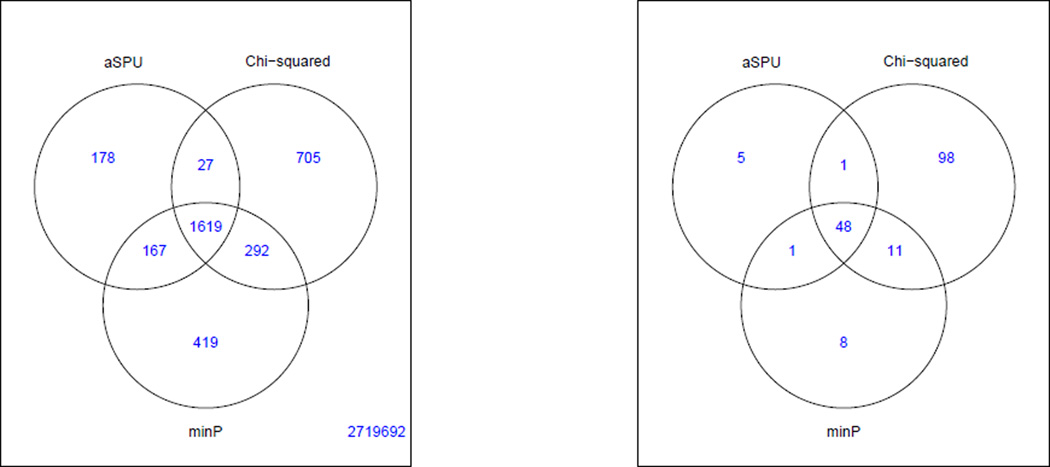

We applied the three tests to each of the SNPs for its possible association with the three lipid traits. At the genome-wide significance level α = 5 × 10−8, the aSPU test identified nine significant SNPs beyond those by the Chi-squared test and the minP test (Figure 1). In total the Chi-squared test identified the largest number of associated SNPs, but the majority of the associated SNPs were identified by all the three methods.

Figure 1.

Venn diagrams for the numbers of the significant SNPs (left panel) and loci (right panel) detected by the three tests at the genome-wide significance level of α = 5 × 10−8.

Given a list of significant SNPs, we followed Ripke et al (2014) to define independent SNPs and associated loci. First, we scan the set of all significant SNPs identified by any of the three multivariate tests. Centering each significant SNP in a window of 500kb, we checked whether it had an LD r2 > 0.1 with any more significant SNPs inside the window; if and only if so, the SNP (in the center of the window) was removed. Then we repeated the process with the next significant SNP. In the end, we identified a set of LD-independent (and significant) SNPs. Second, each LD-independent SNP was used to represent an independent association locus or region: if a significant SNP was between two nearest LD-independent SNPs, it was assigned to the locus of the one in a higher LD (r2) with it; otherwise, it was assigned to that of its nearest LD-independent SNP. In this way, as shown in Figure 1, 76 associated loci were identified by all the three multivariate tests; in addition, 17 additional loci were detected only by the Chi-squared test.

We note that, since the aSPU test was more powerful for testing on a large number of parameters (Zhang et al., 2014; Pan et al., 2015), while in the current application there were only three traits, we suspect that the potential of the aSPU test was not fully demonstrated. For example, if we have summary data from each of the 46 studies, instead of the meta-analyzed summary data available here, it might be easier to see the performance differences among the tests. Next we conducted simulation studies to further investigate the performance of the three tests.

3.2 Simulation I: a single GWAS

We first conducted simulation studies for the case with a single GWAS-based Z-statistics. To be realistic, the simulation set-up mimicked the lipid GWAS data. We studied three quantitative traits (Y1, Y2, Y3)′ simulated from a multivariate normal distribution with unit variance and correlation matrix R = (ρjk). We set the three pairwise correlations as ρ12 = −0.42, ρ13 = 0.27, and ρ23 = −0.08, based on the computed correlation matrix from the lipid GWAS data. We considered two covariates: a binary X1 following a Bernoulli distribution with probability Pr(X1 = 1) = 0.5, and a continuous X2 following the standard normal distribution N(0, 1). We independently simulated m0 null SNPs with the MAF randomly generated from U[0.05, 0.45], and m1 = 96 causal SNPs (G1, …, G96) with the MAF of p0. We set p0 = 0.25 and set the causal SNP effects as follows. We first identified 96 independent loci based on the lipid GWAS summary data. Specifically, we ranked the SNPs based on their minimum univariate p-values and then selected the top SNP within each region. From the reported summary Z-statistics Zkj for SNP j = 1, …, 96 and trait k = 1, 2, 3, we computed their effect sizes as , where N = 105 is roughly the lipidGWAS sample size. We then simulated the three traits based on

with (ε1, ε2, ε3)′ ~ MVN(0, R) for each of n individuals.

We used B = 107 Monte Carlo simulations to estimate significance p-values for SPU tests. We conducted 100 experiments to estimate Type I errors and power. The null SNPs were pooled together for Type I error estimation. We also evaluated the accuracy of correlation matrix estimation using summary statistics and their impact on association testing with summary statistics. We evaluated the performance of the three methods. Specifically, for each simulated dataset, we applied R function lm() to compute a univariate Z-statistic for each SNP-trait association. We then estimated R using the summary Z-statistics, and generated Monte Carlo samples using R package “mvtnorm” to estimate p-values for the aSPU test. We conducted two sets of simulations: n = 103, m0 = 105 and n = 104, m0 = 104.

3.2.1 Estimation of the correlation matrix

As we have shown previously, the correlation of Z-statistics should reflect the correlation of the multiple traits. In the simulation study, there were three components that contributed to the variation of the traits. The first one was the linear component with X1 and X2, which would be adjusted out in the linear model. The second one was the effects of the causal SNPs, for k = 1, 2, 3. And the third one was the random errors εk. When testing the association of null SNPs, the last two components are not adjusted and hence the correlation matrix of null Z-statistics should roughly be the pairwise correlation of ηk+εk, k = 1, 2, 3. For the previous simulation setup, these two components were independent and we easily computed the variance due to ηk. Specifically , where fj was the MAF for SNP j. Here 2fi(1 − fi) = Var(Gi) since we simulated Gi from a Binomial distribution Bin(2, fi). . We then calculated the empirical correlation matrix, leading to (−0.47, 0.31, −0.10), compared to (−0.42, 0.27, −0.08), the true correlations for εk.

We obtained three correlation matrix estimates based on the empirical correlations of the summary statistics of just the null SNPs, all SNPs, and excluding those significant SNPs with a minimum p-value less than 0.05/(m0 + m1)/3. The following table summarizes the results. We can see that using null SNPs and excluding those genome-wide significant SNPs led to very similar results. And all methods gave similar and nearly unbiased estimates. As expected (Table 1), using more samples led to reduced mean squared errors (MSEs).

Table 1.

Bias and root MSE of estimating correlations of (−0.47,0.31,−0.10). There are m0 null SNPs and 96 causal SNPs.

| SNPs used | (n, m0) | Bias | root MSE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All SNPs | (103, 105) | 0.003 | −0.004 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 0.032 |

| (104, 104) | −0.017 | 0.013 | −0.008 | 0.020 | 0.018 | 0.017 | |

| True null SNPs | (103, 105) | 0.004 | −0.004 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 0.032 |

| (104, 104) | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.013 | |

| Estimated null SNPs | (103, 105) | 0.004 | −0.004 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 0.032 |

| (104, 104) | −0.001 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.014 | |

3.2.2 Type I errors

We used the null SNPs to estimate the correlation matrix, then the Type I error rates at various nominal significance levels α, as shown in Table 2. We can see that all methods appropriately controlled the Type I error rates.

Table 2.

Simulation I: Type I errors based on 100 simulations: there are n = 103, 104 unrelated individuals, m0 = 105, 104 null SNPs and m1 = 96 causal SNPs. The type I errors have been scaled by the significance level.

| n = 104, m0 = 104 | ||||||||||||

| SPU(γ) | ||||||||||||

| α | minP | Chi-sq | γ = 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ∞ | aSPU |

| 10−4 | 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 1.22 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.21 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 1.20 | 1.14 |

| 10−3 | 1.03 | 1.04 | 0.96 | 1.07 | 1.02 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.03 |

| n = 103, m0 = 105 | ||||||||||||

| SPU(γ) | ||||||||||||

| α | minP | Chi-sq | γ = 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ∞ | aSPU |

| 10−4 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.12 |

| 10−3 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.04 |

3.2.3 Statistical Power

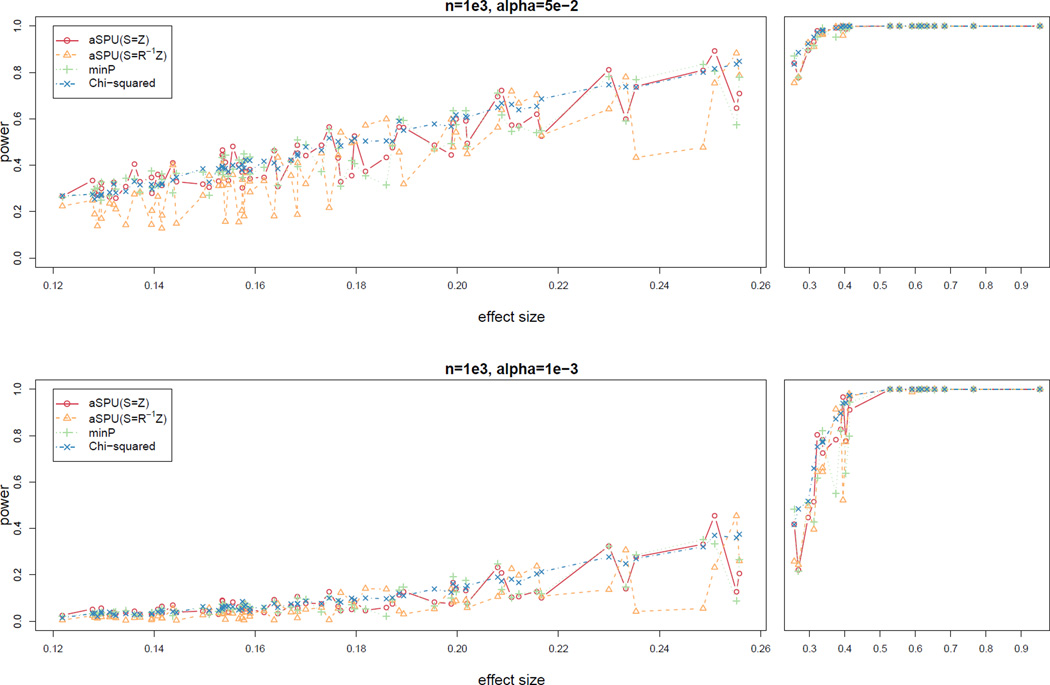

Figure 2 summarizes the empirical power at the nominal significance level α = 0.05 or 0.001 for sample size n = 103. For each causal SNP, we first computed its “effect size” as the non-centrality parameter for the 3-DF Chi-squared test based on the true value of βkj and correlation matrix R of the three traits. We then plotted the power of the tests against the SNP effect size. In each case, we compared the power of the 3-DF Chi-squared test, the minP test and the two versions of the aSPU test. We plotted the power of each test against the effect size of each of the 96 causal SNPs in the panels for better visualization. It can be seen that none of the tests could dominate the others, as expected, since there is no uniformly most powerful test in the current context with multiple parameters being tested. Between the two versions of the aSPU test, it seems that often using transformed Z-statistics (i.e. S = R−1Z) was much lower powered, though sometimes more powerful, than the other version of the aSPU(S = Z) test with the original Z-statistics.

Figure 2.

Simulation I: empirical power of the tests for simulated data with sample size n = 103 and m0 = 105 null SNPs. The nominal significance level α = 0.05 for the top panels and α = 0.001 for the bottom panels.

Figure 3 shows the results with a larger sample size n = 104 and a more stringent nominal significance level at α = 10−6; since all the tests had perfect power for larger effect sizes, we presented empirical power for only smaller effect sizes and only SPU(S = Z). Now the aSPU test appeared to be most powerful for many SNPs, though, as expected, none of the tests could dominate the others. Overall, it is clear that the aSPU test can be a useful and complementary method to the two standard tests.

Figure 3.

Simulation I: empirical power of the three tests for simulated data with sample size n = 104, m0 = 104 null SNPs, and nominal significance level α = 10−6.

3.3 Simulation II: meta analysis

We next considered meta analysis of multiple GWAS cohorts, each giving a set of genome-wide summary Z-statistics. Our simulation set-ups followed that of Zhu et al (2015), offering an opportunity to study the performance of a test in the presence of possible association heterogeneity across multiple traits and/or across multiple studies.

Briefly, in each of five GWAS cohorts, there were three traits, two quantitative ones mimicking systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP) and a binary one for hypertension for 3000 subjects. The SBP and DBP were simulated from a bivariate linear model:

where μ = (127, 78)′ were the population means for SBP and DBP (for gi = 0), gi the additive genotype score for a causal SNP with MAF ~ U(0.01, 0.5), and εi was bivariate normal with mean 0 and covariance matrix V : V11 = 412, V22 = 132 and . The effect size (i.e. each component of β) was chosen so that the phenotypic variance explained by the causal variant was one of 0, 0.1% and 0.3%. The third trait, hypertension (HYT), was binary: HYT=1 if Yi1 > 140 or Yi2 > 90; and HYT=0 otherwise.

Four set-ups were considered in addition to the null (i.e. β = 0). In set-up “Homogeneous (across studies) and Homogeneous (across traits)”, the causal SNP had a common effects on the two quantitative traits SBP and DBP, explaining 0.1% of the total variation of each of SBP and DBP, in all the five cohorts. In set-up “Homogeneous (across studies) and Heterogeneous (across traits)”, the causal SNP had an effect size explaining 0.1% of the total variations of SBP, but no effect on DBP, in all the five cohorts. In set-up “Heterogeneous (across studies) and Homogeneous (across traits)”, the causal SNP had a common effect (explaining 0.3% of the total variations) on SBP and DBP in only the first cohort but not in the other four cohorts. In “Heterogeneous (across studies) and heterogeneous (across traits)”, the causal SNP had an effect on SBP, explaining 0.3% of its total variation, but no effect on DBP, in the first cohort, while it had no effects on any traits in the other four cohorts. In addition to the usual Case 1 with no overlapping subjects, we also considered Case 2 with the presence of cryptic relatedness: 500 subjects in the first cohort also appeared in each of the other four cohorts; the cryptic relatedness could be captured by the estimated correlated matrix R, which was based on the Z-statistics of 10,000 null SNPs. We used the computer program of Zhu et al. (2015) for their two methods. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Simulation II: empirical Type I errors (Null) and power (Homogeneous/Heterogeneous across studies – Homogeneous/Heterogeneous across traits) at the nominal significance level α = 0.05 for five cohorts based on 1000 (and 10000 for two null cases) simulations; there were no (or 500) overlapping subjects across the five cohorts in Case 1 (or Case 2).

| Zhu et al | aSPU | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Set-up | THom | THet | S = Z | S = R−1Z | minP | Chi-sq |

| 1 | Null | 0.049 | 0.022 | 0.037 | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.023 |

| (0.0427) | (0.0457) | (0.0400) | (0.0431) | (0.0393) | (0.0438) | ||

| Homo-Homo | 0.995 | 0.858 | 0.988 | 0.982 | 0.716 | 0.803 | |

| Homo-Hetero | 0.662 | 0.778 | 0.686 | 0.784 | 0.508 | 0.820 | |

| Hetero-Homo | 0.355 | 0.462 | 0.756 | 0.281 | 0.750 | 0.515 | |

| Hetero-Hetero | 0.131 | 0.391 | 0.523 | 0.491 | 0.581 | 0.503 | |

| 2 | Null | 0.057 | 0.028 | 0.060 | 0.038 | 0.057 | 0.023 |

| (0.0486) | (0.0451) | (0.0519) | (0.0480) | (0.0528) | (0.0398) | ||

| Homo-Homo | 0.922 | 0.528 | 0.881 | 0.850 | 0.626 | 0.491 | |

| Homo-Hetero | 0.434 | 0.451 | 0.521 | 0.347 | 0.441 | 0.488 | |

| Hetero-Homo | 0.484 | 0.467 | 0.751 | 0.385 | 0.724 | 0.512 | |

| Hetero-Hetero | 0.180 | 0.400 | 0.506 | 0.466 | 0.555 | 0.520 | |

It can be seen that all the tests could control the Type I error rates satisfactorily. First consider case 1 without any overlapping subjects across the five cohorts. For the case with a homogeneous effect across both cohorts and traits, as expected, the test THomo of Zhu et al (2015) for homogeneity was most powerful; interestingly, the two versions of our proposed aSPU test gave almost the same power, much more powerful than the other three tests; the test THet for heterogeneity and the Chi-squared test followed, while the minP test was least powerful. For the second set-up with a causal SNP with heterogeneous effects on the traits across all the five cohorts, the Chi-squared test was the winner, closely followed by the aSPU(S = R−1Z) and THet tests; the aSPU(S = Z) test was not as powerful as the other version of the aSPU test, but slightly and significantly more powerful than THomo and minP tests respectively. For the third set-up with a homogeneous effect on the traits for only one of the five cohorts, the aSPU(S = Z) and minP tests were the winners, much more powerful than the other tests. It is noted that the transformed Z-statistics S = R−1Z induced a substantial power loss for the aSPU test. For the final set-up with heterogeneity for both the traits and cohorts, the minP test, followed by aSPU(S = Z), then by the Chi-squared and aSPU(S = R−1Z) tests, were more powerful than the two tests of Zhu et al (2015); between the latter two, as expected, THet was much more powerful than THomo.

In Case 2 with overlapping subjects, the main conclusions were the same as before. We just emphasize the following point: In set-ups 2–3 the aSPU(S = Z) test was the most powerful, while it was the second or third most powerful (with power close to the winner) in other two set-ups. Between the two versions of the aSPU test, although they performed similarly in two set-ups, the one using the Z-statistics (S = Z) was much more powerful than the other one for other two set-up.

In summary, our proposed aSPU test was either a winner with the highest power or nearly a winner with power close to the winner across all the situations, presumably due to its adaptivity. Between the two versions of the aSPU test, they sometimes performed similarly; but in some cases using the untransformed Z-statistics (i.e. S = Z) was much more powerful than the other one. Hence, we recommend the use of the aSPU(S = Z) test in practice.

3.4 Application to meta-analyzed anthropometric traits

We applied the methods to the GWAS summary data for six quantitative anthropometric traits: BMI, height, hip, waist circumstances (WC), weight, weight-height ratio (Whr), stratified by sex (Randall et al 2013). A combined dataset for each sex can be regarded as a cohort with six traits, though the sample sizes for the traits ranged from about 30 to 73 thousands. We downloaded the summary data for about 2.7 million SNPs with their association estimates (i.e. regression coefficients) and their standard errors for each sex-specific trait from https://www.broadinstitute.org/collaboration/giant/index.php/GIANT_consortium_data_files.

To achieve the genome-wide significance level at 5e-8, we used B = 109 Monte Carlo simulations to approximate the null distribution to estimate the p-values for the SPU and aSPU tests, which required 30 hours of total computing time on a computer with a single core; we used a computer with multiple cores to speed up. Note that the aSPU test statistics for all the SNPs share the same null distribution, so we only need to estimate the null distribution once, regardless of how many SNPs to be tested. When an estimated p-value was less than 1e-8, we reported its truncated value at 1e-8.

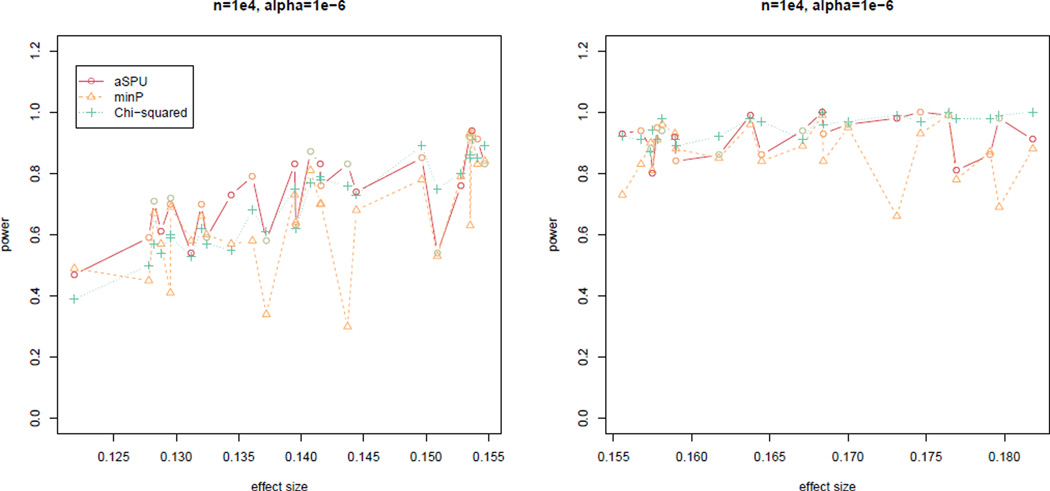

The summary Z statistic for each single SNP–single trait was calculated based on the regression coefficient estimate and its standard error. As discussed, under the null, the joint distribution of the summary Z scores for the individual traits (Z = (Z1, …, Z12)) was assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and correlation matrix R. To estimate R, only (estimated) null SNPs (i.e. those with univariate testing p-values not reaching genome-wide significance) were used. Figure 4 illustrates the estimated correlation matrix for the Z scores. Most pair-wise correlations among the traits were positive. Between the two sexes, the correlations were weak. Only several traits showed strong correlations within sex: BMI and weight showed the highest correlations above 0.80, while those for BMI and WC were around 0.70. Note, however, stronger within-sex correlations were partly due to overlapping subjects.

Figure 4.

The estimated correlation matrix R for the sex-stratified 6 traits.

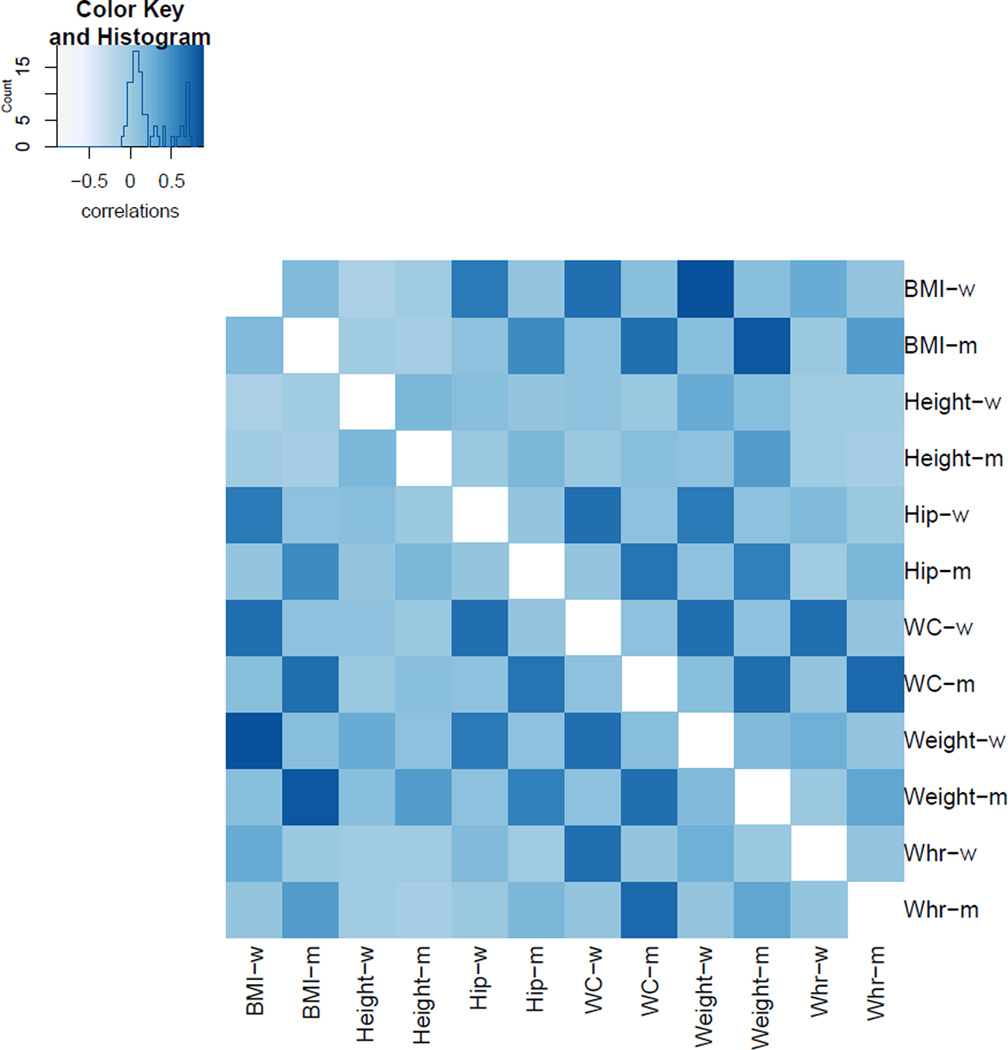

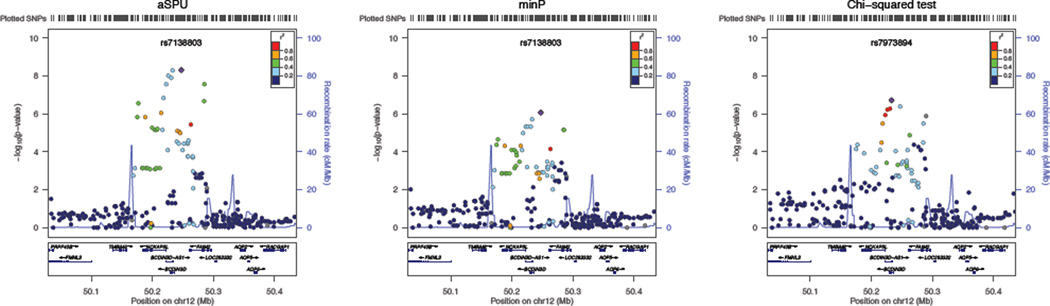

For multi-trait analyses, we applied the minP, Chi-squared and aSPU tests. The minP test identified 2497 significant SNPs associated with the gender-stratified anthropometric traits, and the Chi-squared test found 2643 SNPs, while the aSPU test identified 1991. Figure 5 gives Venn diagrams showing the numbers of the significant SNPs and associated loci identified by the tests. Among 2,723,099 SNPs to be tested, in total 3,407 passed the genome-wide significance level (p-value < 5 × 10−8). The aSPU test identified 178 novel SNPs beyond those given by either the Chi-squared test or the minP test. In particular, a locus composed of 6 SNPs on chromosome 12 (Table 4) was uniquely identified by the aSPU test, and no other SNPs in the region (±1.5 Mbp) were significant by the other two tests. Regional association results from each test are presented in Figure 6 by LocusZoom (Pruim et al 2010). This locus, covering genes BCDIN3D and FAIM2, was found highly associated with BMI, weight, WC or obsessive-compulsive disorder; SNP rs7138803 was highlighted in several GWASs (Stewart et al 2013; Speliotes et al 2010; Heard-Costa et al 2009; Thorleifsson et al 2009). For example, Speliotes et al (2010) reported that SNP rs7138803 was strongly associated with BMI with a p-value=2 × 10−17, while Berndt et al (2013) also indicated its association with a p-value=2×10−9. Interestingly, for this locus, none of the univariate tests for each of the sex-stratified traits could identify any significant associations, though those for BMI and weight were more and marginally significant as shown in Table 5.

Figure 5.

Venn diagrams for the numbers of the significant SNPs (left panel) and loci (right panel) identified by the three multivariate tests.

Table 4.

The p-values for each of 6 SNPs (and their position in bp) by multivariate tests. Only the aSPU test was able to detect significant associations.

| chr | SNP | Position | aSPU | minP | Chi-squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | rs11169170 | 50223013 | 2.7e-08 | 4.56e-06 | 1.11e-06 |

| rs10875976 | 50226467 | 9.0e-09 | 4.56e-06 | 6.18e-07 | |

| rs4898534 | 50231025 | 1.2e-08 | 4.56e-06 | 5.32e-07 | |

| rs7973894 | 50233256 | 5.0e-09 | 1.93e-06 | 1.92e-07 | |

| rs7138803 | 50247468 | 4.0e-09 | 8.44e-07 | 3.92e-07 | |

| rs17201502 | 50285562 | 2.7e-08 | 6.82e-06 | 3.38e-06 |

Figure 6.

A locus identified by the aSPU test, but not by the other two tests.

Table 5.

The p-values for each of 6 SNPs by the univariate test. None of significant associations was detected.

| BMI | height | hip | WC | weight | Whr | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women |

| rs11169170 | 1.01e-06 | 8.97e-06 | 7.8e-01 | 6.0e-03 | 3.4e-03 | 1.9e-03 | 1.1e-02 | 3.9e-04 | 3.12e-06 | 6.84e-07 | 5.8e-01 | 5.8e-02 |

| rs10875976 | 3.68e-07 | 8.34e-06 | 8.3e-01 | 5.4e-03 | 1.7e-03 | 1.1e-03 | 6.2e-03 | 4.0e-04 | 1.19e-06 | 4.95e-07 | 5.3e-01 | 5.8e-02 |

| rs4898534 | 4.36e-07 | 1.20e-05 | 7.8e-01 | 6.0e-03 | 2.2e-03 | 1.3e-03 | 8.2e-03 | 5.7e-04 | 1.40e-06 | 8.03e-07 | 5.9e-01 | 8.4e-02 |

| rs7973894 | 2.84e-07 | 6.69e-06 | 8.9e-01 | 7.3e-03 | 1.3e-03 | 1.2e-03 | 7.0e-03 | 4.0e-04 | 7.29e-07 | 5.37e-07 | 5.6e-01 | 6.5e-02 |

| rs7138803 | 1.25e-07 | 8.84e-06 | 6.0e-01 | 6.4e-02 | 4.4e-04 | 7.3e-05 | 1.5e-03 | 1.9e-03 | 9.94e-08 | 4.08e-06 | 5.1e-01 | 1.8e-01 |

| rs17201502 | 1.29e-06 | 8.60e-05 | 9.1e-01 | 6.4e-02 | 1.8e-04 | 1.7e-04 | 4.4e-03 | 1.5e-03 | 9.55e-07 | 5.82e-06 | 6.3e-01 | 1.0e-01 |

4 Discussion

In this paper we have extended the SPU and aSPU tests to multi-trait association analysis using only GWAS summary statistics. The SPU and aSPU tests compute their significance p-values based on Monte Carlo simulations, as the two new tests of Zhu et al. (2015). Although it is computationally demanding, we have demonstrated its feasibility in the applications to two meta-analyzed GWAS datasets. Note that the null distribution of a test statistic only needs to be estimated once for each genome-wide dataset, and it can be repeatedly used for each of the SNPs to be tested. Furthermore, a step-up procedure can be used to reduce computing time: one starts from a relatively small B for a genome-wide scan, and gradually increases B for those SNPs meeting an increasing significance level. Because the overwhelming majority of the SNPs are not highly significant, they only requre a smaller value of B.

For the typical situation with only one set of possibly meta-analyzed genome-wide Z-summary statistics, we have compared the performance of the proposed aSPU test with two standard approaches: a Chi-squared test and the minP test. In general, the minP test is suitable if only one or few traits are associated with the SNP with a large effect size; otherwise it will lose power. In particular, if there are multiple traits associated with the same SNP with only small to moderate effect sizes, the aSPU and Chi-squared tests are expected to be more powerful. As the number of the traits increases, due to an increasing number of degrees of freedom, the Chi-squared test, as the GEE-Score test, may lose power, as shown in Zhang et al. (2014). On the other hand, due to the versatile SPU tests, the aSPU test can be adaptive to various association patterns, e.g. a varying number of associated traits and their varying effect sizes or directions, thus achieving high power. In particular, since only three univariate traits were considered in the lipid data analysis, we suspect that the potential of the proposed aSPU test was not fully demonstrated; in contrast, in the analysis of a larger number of anthropometric traits, the aSPU test better demonstrated its ability to identify some significant associations that would be missed by other tests, though the Chi-squared test still appeared to be more powerful. As shown in Zhang et al. (2014), in the context with individual-level genotype and phenotype data, as the number of the traits increased, the aSPU test showed a larger power advantage over the Chi-squared test in some situations. In particular, if all the traits are associated with the same SNP, surprisingly the Chi-squared test may lose power. Nevertheless, in other situations, as shown in our two real data examples, the Chi-squared test (or more generally, the score test or MANOVA) might be more powerful; Zhang et al (2014) proposed an approach to combine the strengths of the aSPU test and the score test, which could maintain high power across all the scenarios and might be adopted here.

We also explored the direct application of our proposed tests to meta analysis of multiple sets of Z-summary statistics, each based on a GWAS (or a meta analysis of multiple GWASs). As shown by Zhu et al. (2015), it is critical to consider heterogeneous effects of an SNP across multiple traits and multiple GWASs. For example, due to different populations across the studies, one SNP may be associated with a subset, not all, of the traits in only a proper subset of the studies. Under these situations, a typical meta-analysis may lose power by ignoring the problem of effect heterogeneity; publishing summary statistics for each individual study, not just the meta-analyzed one, is not the current practice but is expected to offer more information. In particular, we note that, in the presence of association heterogeneity, the usual fixed-effects meta analysis and its efficiency results (Lin and Zeng, 2010a,b) are not applicable; furthermore, the efficiency result of the random-effects meta analysis (Lin and Zeng, 2015) is only for the estimator of the mean effect size, not for hypothesis testing as considered here. In these situations, due to the increasing number of the traits (more accurately, trait-study interactions), the adaptivity of a test becomes even more important. Our simulation studies confirmed the superior performance of the aSPU test in such situations. Although we have focused on multiple traits, the aSPU test can be equally applied to meta analysis of a single trait, especially for its adaptivity in the presence of association heterogeneity across the studies.

Finally, we note that most of the existing methods for analysis of multivariate traits require the use of individual-level genotype and phenotype data, which may be difficult to obtain by the third party. On the other hand, in the post-GWAS era, many summary GWAS results have been reported. The proposed methods provide a cost-effective way to analyze these summary data without requiring access to individual-level genotype and phenotype data, and thus may quickly provide additional results and insights.

The methods are implemented in R package aSPU, which will be available on the corresponding author’s web site and CRAN.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the reviewers for helpful comments. This research was supported by NIH grants R01GM113250, R01HL105397 and R01HL116720, and by the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute. JK was supported by a UMII MnDRIVE fellowship and YB by NIH grant T32 GM108557.

References

- Aschard H, Vilhjalmsson B, Wu C, Greliche N, Morange PE, Wolpin B, Tregouet DA, Kraft P. Maximizing the power in principal components analysis of correlated phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:662–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt SI, Gustafsson S, Mägi R, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 11 new loci for anthropometric traits and provides insights into genetic architecture. Nature Genetics. 2013;45:501–512. doi: 10.1038/ng.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolormaa S, Pryce JE, Reverter A, Zhang Y, Barendse W, et al. A Multi-Trait, Meta-analysis for Detecting Pleiotropic Polymorphisms for Stature, Fatness and Reproduction in Beef Cattle. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(3):e1004198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung D, Yang C, Li C, Gelernter J, Zhao H. GPA: a statistical approach to prioritizing GWAS results by integrating pleiotropy and annotation. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conneely KN, Boehnke M. So many correlated tests, so little time! Rapid adjustment of P values for multiple correlated tests. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1158–1168. doi: 10.1086/522036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MAR, Purcell SM. A multivariate test of association. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(1):132–133. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galesloot TE, van Steen K, Kiemeney LALM, Janss LL, Vermeulen SH. A comparison of multivariate genome-wide association methods. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e95923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Avery CL, Lin DY. A general framework for association tests with multivariate traits in large-scale genomics studies. Genetic Epidemiology. 2013;37(8):759–767. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard-Costa NL, Zillikens MC, Monda KL, et al. NRXN3 Is a Novel Locus for Waist Circumference: A Genome-Wide Association Study from the CHARGE Consortium. PLoS Genetics. 2009;5(6):e1000539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Wozniak JR, Mueller BA, Shen X, Pan W. Comparison of statistical tests for group differences in brain functional networks. Neuroimage. 2014;101:681–694. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klei L, Luca D, Devlin B, Roeder K. Pleiotropy and principal components of heritability combine to increase power for association analysis. Genetic Epidemiology. 2008;32(1):9–19. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan H, Stoehr J, Nadler S, Schueler K, Yandell B, Attie A. Dimension reduction for mapping mRNA abundance as quantitative traits. Genetics. 2003;164:1607–1614. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Yang C, Gelernter J, Zhao H. Improving genetic risk prediction by leveraging pleiotropy. Hum Genet. 2014;133:639–650. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1401-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Sullivan PF. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies with overlapping subjects. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2009;85:862–872. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Zeng D. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies: no efficiency gain in using individual participant data. Genetic Epidemiology. 2010;34:60–66. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Zeng D. On the relative efficiency of using summary statistics versus individual level data in meta-analysis. Biometrika. 2010b;97:321–332. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Zeng D. On random-effects meta-analysis. Biometrika. 2015 doi: 10.1093/biomet/asv011. to appear. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Zhu HT, Knickmeyer R, Styner M, Gilmore JH, Ibrahim JG. Projection Regression Models for Multivariate Imaging Phenotype. Genetic Epidemiology. 2012;36:631–641. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity A, Sullivan PF, Tzeng JY. Multivariate phenotype association analysis by marker-set kernel machine regression. Genet Epidemiol. 2012;36:686–695. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien PC. Procedures for comparing samples with multiple endpoints. Biometrics. 1984;40:1079–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly PF, Hoggart CJ, Pomyen Y, Calboli FC, Elliott P, Jarvelin M-R, Coin LJ. MultiPhen: joint model of multiple phenotypes can increase discovery in GWAS. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W. Asymptotic tests of association with multiple SNPs in linkage disequilibrium. Genetic Epidemiology. 2009;33:497–507. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Kim J, Zhang Y, Shen X, Wei P. A powerful and adaptive association test for rare variants. Genetics. 2014;197:1081–1095. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.165035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Chen Y, Wei P. Testing for polygenic effects in genome-wide association studies. Genetic Epidemiology. 2015;39:306–316. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR, Willer CJ. LocusZoom: Regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–2337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall JC, Winkler TW, Kutalik Z, et al. Sex-stratified Genome-wide Association Studies Including 270,000 Individuals Show Sexual Dimorphism in Genetic Loci for Anthropometric Traits. PLoS Genetics. 2013;9:e1003500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripke S, Neale BM, Corvin A, Walters JT, Farh K-H, Donovan MC. Biological Insights From 108 Schizophrenia-Associated Genetic Loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano ED, Epstein MP, Bielak LF, Jhun MA, Kardia SL, Peyser PA, Lin X. SNP Set Association Analysis for Familial Data. Genet Epidemiol. 2012;36:797–810. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Kim S, Risacher SL, Nho K, Swaminathan S, West JD, Foroud T, Pankratz N, Moore JH, Sloan CD, et al. Whole genome association study of brain-wide imaging phenotypes for identifying quantitative trait loci in MCI and AD: a study of the ADNI cohort. Neuroimage. 2010;53:1051–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal eighteen new loci associated with body mass index. Nature Genetics. 2010;42:937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M. A unified framework for association analysis with multiple related phenotypes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e65245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SE, Yu D, Scharf JM, et al. Genome-wide Association Study of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2013;18:788–798. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466(7307):707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluis S, Posthuma D, Dolan CV. TATES: efficient multivariate genotype-phenotype analysis for genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(1):e1003235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. Testing Genetic Association by Regressing Genotype over Multiple Phenotypes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e106918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Abbott D. A principal components regression approach to multilocus genetic association studies. Genetic Epidemiology. 2008;32(2):108–118. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Kammerer CM, Anderson S, Lu J, Feingold E. A comparison of principal component analysis and factor analysis strategies for uncovering pleiotropic factors. Genetic Epidemiology. 2008;33:325–331. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Morris NJ, Zhu X, Elston RC. A variance component based multi-marker association test using family and unrelated data. BMC Genetics. 2013;14:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lee S, Zhu X, Redline S, Lin X. GEE-Based SNP Set Association Test for Continuous and Discrete Traits in Family-Based Association Studies. Genetic Epidemiology. 2013b;37:778–786. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liu A, Mills JL, Boehnke M, Wilson AF, Bailey-Wilson JE, Xiong M, Wu CO, Fan R. Pleiotropy Analysis of Quantitative Traits at Gene Level by Multivariate Functional Linear Models. 2015 doi: 10.1002/gepi.21895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MC, Kraft P, Epstein MP, Taylor DM, Chanock SJ, Hunter DJ, Lin X. Powerful SNP-Set Analysis for Case-Control Genome-wide Association Studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:929–942. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Wu H, Guo CY, Fox CS. Analyze multivariate phenotypes in genetic association studies by combining univariate association tests. Genetic Epidemiology. 2010;34(5):444–454. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Wang Y. Methods for analyzing multivariate phenotypes in genetic association studies. Journal of Probability and Statistics. 2012:652569. doi: 10.1155/2012/652569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Liu C-T, Wang X. An association test for multiple traits based on the generalized Kendall’s tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2010;105:473–481. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xu Z, Shen X, Pan W. Testing for association with multiple traits in generalized estimation equations, with application to neuroimaging data. NeuroImage. 2014;96:309–325. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Zhang H. Why do we test multiple traits in genetic association studies? J. Korean Stat. Soc. 2009;38:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jkss.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Feng T, Tayo B, Liang J, Young JH, Franceschini N, Smith J, Yanek L, Sun Y, Edwards T, Chen W, Nalls M, Fox E, Sale M, Bottinger E, Rotimi C, Liu Y, McKnight B, Liu K, Arnett D, Chakravati A, Cooper R, Redline S. Meta-analysis of correlated traits via summary statistics from GWASs with an application in hypertension. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2014;96:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]