Abstract

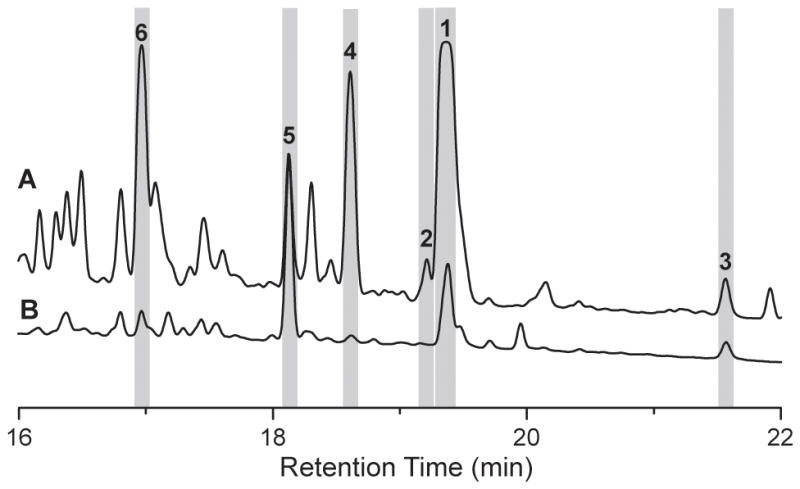

Salinamide A belongs to a rare class of bicyclic depsipeptide antibiotics in which the installation of a (4-methylhexa-2,4-dienoyl)glycine handle across a hexadepsipeptide core contributes to its chemical complexity and biological properties. Here we report the genetic and biochemical basis for salinamide construction in the marine bacterium Streptomyces sp. CNB-091 that involves a novel intermolecular transesterification reaction catalyzed by a type I thioesterase. Heterologous biosynthesis studies revealed the central role of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase Sln9 in constructing and installing salinamides distinctive acylglycine “basket” handle. Biochemical characterization of the Sln9 thioesterase domain established the transesterification of desmethylsalinamide E’s serine residue with acylated glycyl thioesters to yield desmethylsalinamide C.

Keywords: biosynthesis, coupling, intermolecular, peptides, thioesterase

Graphical Abstract

Uncovering the biosynthetic logic for salinamide A assembly has illuminated a type I thioesterase, encoded within a tetradomain non-ribosomal pepetide synthetase (NRPS) module, as playing a pivotal role in the installation of an acyl-glycine handle across the relatively simple hexadepsipeptide core. Catalyzing an intermolecular peptidyl transesterification, this unprecedented reaction mediates the transfer of an acylated glycine from a carrier protein (CP) to a serine hydroxyl group within an offloaded non-ribosomal peptide product.

Non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs) have long been recognized as a highly diverse and important class of natural products, both in terms of structure and function.[1] Their construction by large, multifunctional assembly line proteins involves ATP-dependent activation and transfer of amino acid precursors to arrayed carrier protein (CP) domains. Once the mature peptide intermediate is assembled by the non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), a myriad of protein off-loading reactions await to yield the released peptide product.[2] The most common terminating reaction is catalyzed by thioesterase (TE) proteins that typically occupy the terminal domain of the NRPS and function to release the product as linear or macrocyclized peptides.[3] Here, we report a new role for a terminating TE that involves an intermolecular transesterification reaction associated with the construction of the salinamides, a family of unusual bicyclic depsipeptides that exhibit anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties.

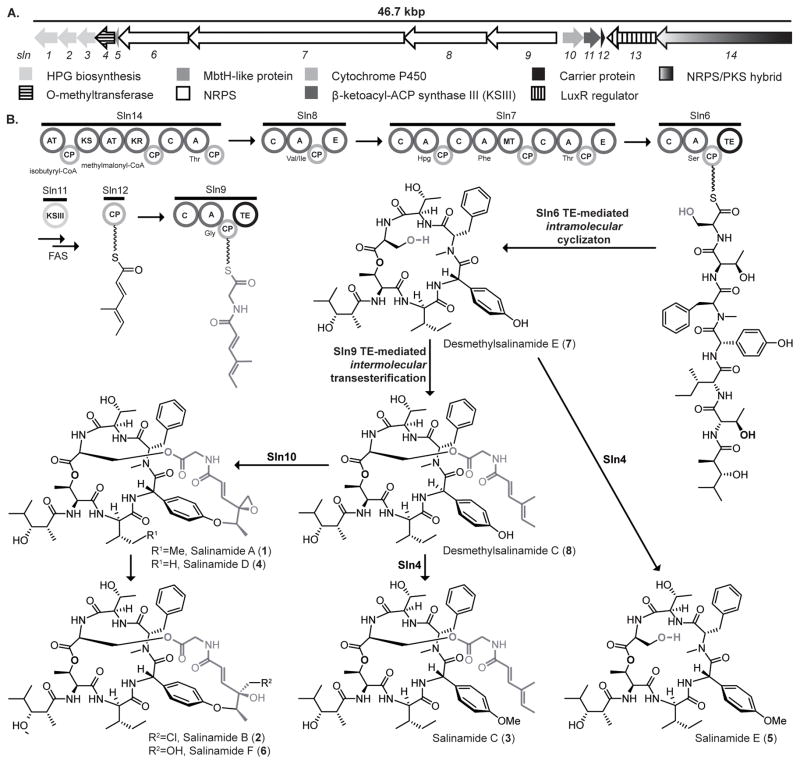

The first in this class of depsipeptides to be isolated from the marine actinomycete Streptomyces sp. CNB-091 were salinamides A (1) and B (2).[4] This series of NRPs has since been expanded through the isolation and characterization of various derivatives to include salinamides C (3), D (4), E (5) and F (6).[5] All salinamides share a common depsipeptide core comprised of a beta-hydroxyacid moiety derived from isobutyrate and propionate, and six amino acid residues – L-serine, L-phenylalanine, p-hydroxy-L-phenylglycine (p-HPG), L-threonine, D-threonine and D-isoleucine (or D-valine in the case of 4). The simplest of the salinamide derivatives, 5, is methylated at the p-HPG position. The remaining salinamide derivatives are all decorated with a (4-methylhexa-2,4,-dienoyl)glycine moiety tethered to the serine hydroxyl group (Ser-OH) via an ester bond. Within 1, 2, 4 and 6 this extended serine side chain is cyclized onto the phenoxyl group of the p-HPG residue (p-HPG-OH) to create a “basket” handle across the cyclic core. Probing the metabolic origins of the carbon residues within the salinamides previously revealed that the Ser-modified acylglycine side chain is derived from the condensation of 2-methylbutyrate and malonate (Figure 1).[6]

Figure 1.

(A) Gene organization of the salinamide (sln) biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces sp. CNB-091 (see Supporting Information for the proposed function assignments of the coding sequences). (B) Proposed biosynthesis of salinamides. The A domain of Sln8 is able to accept isoleucine and valine; consequently two different salinamide series are biosynthesized. All ‘Ile’ derivatives, 1–3 and 5–8, are illustrated within this figure, however 4 is the only ‘Val’ derivative represented as it is a significant pathway product (see Figure 2). Abbreviations: A, adenylation; AT, acyltransferase; C, condensation; CP, carrier protein; E, epimerization; FAS, fatty acid synthase; p-HPG, hydroxyphenylglycine; KR, ketoreductase; KS, ketosynthase;; MT, methyltransferase; TE, thioesterase.

Identification of this series of salinamide derivatives and the isotope incorporation data suggests the involvement of a novel biosynthetic pathway, in which a mature cyclic depsipeptide is processed by the addition of a (4-methylhexa-2,4,-dienoyl)glycine unit to the Ser-OH. Subsequent oxidative cyclization of this side chain onto p-HPG-OH would yield the bicylic depsipeptide 1. This biosynthetic scenario suggested the possibility of new peptide side chain modification enzymology involving a CP-bound substrate. Precedent examples are nonexistent. Thiotemplated assembly line synthesis of ester linkages are known to involve NRPS condensation (C) domain chemistry, such as for the didemnins and hectochlorins, in which hydroxyacid rather than amino acid building blocks are incorporated into NRP products.[7] That scenario however does not fit salinamide assembly in which the ester is derived in a very different manner involving a side chain hydroxyl. Standalone C-domains are rather known from polyketide biosynthesis to attach carboxylic acid substrates to ketide hydroxyls as in C-1027 and fumonisin biosynthesis.[8] Although this mechanism is plausible for salinamide esterification, we show a new role for a terminal TE domain in catalyzing a transesterification reaction.

To understand the mechanism responsible for the installation of the salinamide “handle”, we obtained a draft genome sequence of Streptomyces sp. CNB-091. The high quality of this draft sequence resulted in the 8.2 Mbp genome being split across 50 scaffolds, with a GC content of 71.6%. Subsequent bioinformatic analysis of this draft genome unveiled the full biosynthetic potential of Streptomyces sp. CNB-091.[9] A vast array of putative secondary metabolite gene clusters were illuminated, with a total of 38 clusters encoding the synthesis of polyketides, NRPs, terpenes and ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products. Intriguingly the salinamides are, to date, the only class of molecules reported from Streptomyces sp. CNB-091, thus indicating that Streptomyces sp. CNB-091 is a relatively untapped resource with regards to its potential to produce diverse natural products.

From the 38 biosynthetic gene clusters, we identified a single candidate cluster for salinamide biosynthesis. This 47.6 kbp, 14 coding sequence NRPS-polyketide synthase (PKS) hybrid gene cluster was designated the sln locus (Figure 1a). The sln cluster contains four genes encoding NRPS proteins and one encoding a PKS/NRPS hybrid, and genes encoding enzymes responsible for precursor biosynthesis and post-NRPS tailoring enzymes. Significantly, the domain structure and module organization of the encoded NRPS-PKS megasynthetase was consistent with the structures of the salinamides in which two amino acid residues are D configured (Val/Ile-2 and Thr-5) and another (Phe-4) is methylated.[10] Moreover genes supporting the biosynthesis of the non-proteinogenic amino acid residue p-HPG were subclustered in a gene cassette (sln1-3).[11] One salient feature of the sln cluster is the presence of two genes, sln6 and sln9, both of which encode tetradomain NRPS modules containing a C-terminal TE domain. This led to the proposal that one of these type I TE domains play a central role in the addition of the (4-methylhexa-2,4,-dienoyl)-glycine moiety onto the Ser-OH, rather than this being the product of C domain chemistry (Figure 1B).

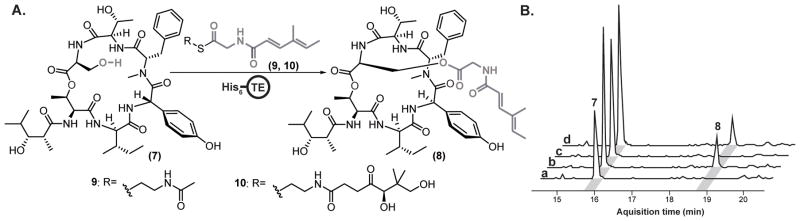

To validate that this putative biosynthetic gene cluster is responsible for the production of salinamides, we directly captured the sln locus from gDNA via yeast-based transformation associated recombination (TAR) in the multipurpose expression plasmid pCAP01.[12] Following capture, the sln cluster was integrated into the genome of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor M1146 for heterologous expression.[13] Fermentation of this genome minimized strain revealed the production of the full suite of salinamides, confirming the sln locus is responsible for salinamide biosynthesis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

HPLC analysis of salinamide production in the native S. sp. CNB-091 (A) and the heterologous host S. coelicolor M1146 into which the pCAPsln vector has been integrated (B). UV absorption at 210 nm was monitored and the peaks corresponding to salinamides A–F (1–6) are highlighted.

Successful capture and heterologous expression of the salinamide gene cluster provided a mechanism by which to interrogate the in vivo biosynthesis of salinamides. We deleted several sln genes via λ-Red mediated recombination and analyzed chemical extracts of the mutants by HPLC-MS. Firstly we focused upon the biosynthesis of the salinamide depsipeptide core via the canonical NRPS/PKS hybrid. This was probed through the deletion of sln6, which encodes the putative final module in this assembly line terminating with the cyclizing TE. As anticipated, this mutation completely abolished salinamide production (Figure S1-C). A loss of salinamide production was also observed upon deletion of the LuxR regulatory protein (Figure S1-B). We then turned out attention to the tailoring genes within the pathway. Deletion of the O-methyltransferase sln4 resulted in the loss in production of 3 and 5 with concomitant production of 1 and a new desmethylsalinamide, the postulated intermediate 7, which was subsequently isolated and characterized via HR-MS and NMR spectroscopy (Figure S1-F). The production of 1 was uniquely abolished with the deletion of the cytochrome P450 (CYP450)-encoding sln10 gene, as all other salinamides including 3 and 5, were maintained in the mutant (Figure S1-E). This observation is highly suggestive that the CYP450 is responsible for catalyzing the closure of the salinamide A basket handle between the p-HPG and the side chain diene. Furthermore these results suggest that 3 and 5 are end of pathway products rather than intermediates towards the more chemically elaborate 1 (Figure 1B).

We next focused on the biosynthesis of the N-acylated glycine moiety and the mode of its transfer to the Ser-OH in 1 and 3. Previously we showed that the acyl diene fragment originates from the condensation of isoleucine-derived tiglic acid and acetate,[6] which is consistent with the activity of FabH-based enzymology. We thus deleted the FabH homologue sln11. Whilst the level of production of 5 was maintained, the production of all other salinamide derivatives was significantly reduced, suggesting genetic complementation by a host FabH gene (Figure S1-D). Inactivation of the Sln9 NRPS gene resulted in the elimination of 1 and 3 while maintaining the production of 5 and 7 (Figure S1-G). Based on these outcomes, we surmise that the tetradomain Sln9 activates glycine, condenses it with the Sln11 product 4-methyl-2,4-hexadienoyl-S-Sln12, and, involving unprecedented TE domain chemistry, transfers the acylglycine substrate to the Ser-OH residue in 7 to yield 8. This proposed activity would signal a departure from the NRPS assembly line paradigm in which TEs normally catalyze offloading hydrolytic or intramolecular reactions, much like that observed with the C-terminal TE domain of Sln6.[14]

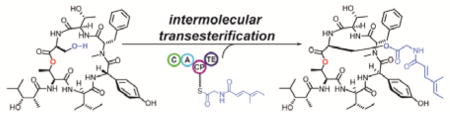

To explore this proposal, we biochemically characterized the Sln-TE. We isolated the presumed substrate 7 from fermentation broths of the ΔSln4 MT mutant and synthesized two acylglycine-CP substrate mimics as N-acetylcysteamine and N-pantatheinylcysteamine thioesters (9 and 10, Figure 3a).[15] We also cloned, expressed and purified the recombinant hexahistadyl-tagged Sln9-TE domain (Figure S17). Indeed, as hypothesized, upon incubation of His6-Sln9-TE with 7 and the acylglycine-CP substrate mimics, 9 or 10, we were able to observe the transfer of the acylglycine moiety onto the Ser-OH. This confirms that Sln9-TE represents the first example of an intermolecular-acting TE domain within a bacterial NRPS (Figure 3). This observation increases the scope of TE domain chemistry to include the modification of NRP side chains through the transesterification of peptidyl substrates.

Figure 3.

Biochemical characterization of the Sln9 type I TE domain with 7 as a substrate, 5 was also accepted as a substrate for Sln9-TE; the results of which are shown in Figure S19. (A) Intermolecular transesterification reaction catalyzed by the Sln9-TE domain. Synthesis of substrates 9 and 10 and the preparation of recombinant hexahistidine-tagged Sln9-TE are described in the Supporting Information; (B) HR-LCMS analysis of the Sln9 TE reaction, all traces are extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) for m/z 841.43 ([M+H]+ ion for 7) and 1006.51 ([M+H]+ ion for 8) (a) Control assay with heat-inactivated His6-Sln9-TE domain using 9 as a substrate; (b) His6-Sln9-TE domain enzymatic assay showing the conversion of 7 to 8 using substrate 9; (c) Control assay with heat-inactivated His6-Sln9-TE domain using 10 as a substrate; and (d) His6-Sln9-TE domain enzymatic assay showing conversion of 7 to 8 using substrate 10.

In conclusion, we have successfully characterized the biosynthetic logic of salinamide assembly. Direct capture of the salinamide biosynthetic gene cluster via TAR cloning facilitated heterologous expression studies which allowed for the genetic interrogation of the sln gene locus. Significantly, this work uncovered the first example of an intermolecular-acting TE domain within a bacterial NRPS to mediate the transesterification of a CP-bound substrate to a cyclic depsipeptide. Investigations to probe the substrate specificity of this TE are currently ongoing along with efforts to understand the structural features that enable the controlled acylation of peptide substrates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our UCSD colleagues B. M. Duggan for assistance with NMR data acquisition, W. Fenical and P. R. Jensen for Streptomyces sp. CNB-091, and V. Agarwal, S. M. Mantovani, and S. Diethelm for helpful discussions. Funding was generously provided by NIH grants R01-GM085770 and R01-AI047818.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://xxxxxxxx

Contributor Information

Dr. Lauren Ray, Center for Marine Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla CA 92037 (USA)

Dr. Kazuya Yamanaka, Center for Marine Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla CA 92037 (USA). Yokohama Research Center, JNC Corporation, Yokohama 236-8605 (Japan)

Prof. Dr. Bradley S. Moore, Email: bsmoore@ucsd.edu, Center for Marine Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla CA 92037 (USA). Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla CA 92037 (USA), Homepage: http://scrippsscholars.ucsd.edu/bsmoore

References

- 1.Sieber SA, Marahiel MA. Chem Rev. 2005;105:715–738. doi: 10.1021/cr0301191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horsman ME, Hari TP, Boddy CN. Nat Prod Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1039/C4NP00158F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Trischman JA, Tapiolas DM, Jensen PR, Dwight R, Fenical W, McKee TC, Ireland CM, Stout TJ, Clardy J. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:757–758. [Google Scholar]; b) Miao SC, Anstee MR, LaMarco K, Matthew J, Huang LHT, Brasseur MM. J Nat Prod. 1997;60:858–861. [Google Scholar]; c) Degen D, Feng Y, Zhang Y, Ebright KY, Ebright YW, Gigliotti M, Vahedian-Movahed H, Mandal S, Talaue M, Connell N, Arnold E, Fenical W, Ebright RH. eLife. 2014;3:e02451. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Moore BS, Trischman JA, Seng D, Kho D, Jensen PR, Fenical W. J Org Chem. 1999;64:1145–1150. [Google Scholar]; b) Hassan HM, Degen D, Jang KH, Ebright RH, Fenical W. J Antibiot. 2015;68:206–209. doi: 10.1038/ja.2014.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore BS, Seng D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:3915–3918. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Xu Y, Kersten RD, Nam SJ, Lu L, Al-Suwailem AM, Zheng H, Fenical W, Dorrestein PC, Moore BS, Qian PY. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8625–8632. doi: 10.1021/ja301735a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ramaswamy AV, Sorrels CM, Gerwick WH. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1977–1986. doi: 10.1021/np0704250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Zaleta-Rivera K, Xu CP, Yu FG, Butchko RAE, Proctor RH, Hidalgo-Lara ME, Raza A, Dussault PH, Du LC. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2561–2569. doi: 10.1021/bi052085s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lin S, Van Lanen SG, Shen B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4183–4188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808880106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Ziemert N, Podell S, Penn K, Badger JH, Allen E, Jensen PR. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R, Lee SY, Fischbach MA, Mueller R, Wohlleben W, Breitling R, Takano E, Medema MH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Stachelhaus T, Mootz HD, Marahiel MA. Chem Biol. 1999;6:493–505. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Challis GL, Ravel J, Townsend CA. Chem Biol. 2000;7:211–224. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hubbard BK, Thomas MG, Walsh CT. Chem Biol. 2000;7:931–942. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamanaka K, Reynolds KA, Kersten RD, Ryan KS, Gonzalez DJ, Nizet V, Dorrestein PC, Moore BS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1957–1962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319584111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Escribano JP, Bibb MJ. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4:207–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) More recently the breadth of reactions catalyzed by TEs has expanded extensively, including dehydration for cis-double bond formation in FR901464 biosynthesis and epimerization in nocardicin biosynthesis, however they are all fundamentally intramolecular reactions Gaudelli NM, Townsend CA. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:251–258. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1456.He HY, Tang MC, Zhang F, Tang GL. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4488–4491. doi: 10.1021/ja500942y.

- 15.Agarwal V, Diethelm S, Ray L, Garg N, Awakawa T, Dorrestein PC, Moore BS. Org Lett. 2015;17:4452–4455. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.