Abstract

This study aims at analysing the impact of international service trade on the health care system, particularly in terms of human resources for health (HRH), using Thailand as a case study. Information was gathered through a literature review and interviews of relevant experts, as well as a brainstorming session.

It was found that international service trade has greatly affected the Thai health care system and its HRH. From 1965 to 1975 there was massive emigration of physicians from Thailand in response to increasing demand in the United States of America. The country lost about 1,500 physicians, 20% of its total number, during that period.

External migration of health professionals occurred without relation to agreements on trade in services. It was also found that free trade in service sectors other than health could seriously affect the health care system and HRH. Free trade in financial services with free flow of low-interest foreign loans, which started in 1993 in Thailand, resulted in the mushrooming of urban private hospitals between 1994 and 1997. This was followed by intensive internal migration of health professionals from rural public to urban private hospitals.

After the economic crisis in 1997, with the resulting downturn of the private health sector, reverse brain drain was evident. At the same time, foreign investors started to invest in the bankrupt private hospitals. Since 2001, the return of economic growth and the influx of foreign patients have started another round of internal brain drain.

Introduction

In recent years, the growth of trade in the global economy has rapidly increased. The size of international trade in 1996 was estimated at USD 6 trillion, and 20%-25% of this was trade in services [1]. In both developed and developing countries, international trade accounts for an increasing share of gross domestic product (GDP). For example, Thailand's total exports in 2001 were worth 3,386,088 million Baht, or 60% of the GDP of 5,079,018 million Baht [2].

In 1996 the size of the global health services sector was estimated at USD 3 trillion. The figure estimated for 2005 is USD 4 trillion [3]. Most of this is in domestic markets. It was estimated that the value of global health services exported in 2000 amounted to USD 140 billion, less than 5% of the global market, and that this was growing at 6% per year [4]. But this percentage may grow rapidly with more widespread use of information and communications technology – for example, e-health – and as health systems are liberalized and entry barriers are lowered[5].

The World Trade Organization (WTO), established in 1995, aims to reduce unnecessary trade barriers. The main WTO agreements related to health include the Agreements on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT), the Agreement on Sanitary and Phyto-sanitary Measures (SPS), the Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) and the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) [6]. Many regional trade agreements follow more or less the same principles as WTO agreements. Among South-East Asia nations, for example, there is the ASEAN Free Trade Area with its ASEAN Free Trade Agreement on Services (AFAS).

Several possible implications of the international trade on health systems are related mainly to social equity[3]. First, the beneficial effects of telemedicine are offset by the required infrastructure and the manpower tradeoff versus basic services for the poor. Second, consumption abroad can result in a dual market structure that siphons scarce health resources from the poor. Third, although a foreign commercial presence can reduce pressure on public resources, it also can lead to a tiered health care system, with flow of providers from the rural public health sector to the urban private health sector. Finally, although movement of health personnel may create opportunities for remittances to developing countries, the resultant brain drain is a serious constraint for national health system development.

Some questions that need to be addressed in the context of a developing country are related to the impact of liberalized trade in health services on the cost, quality, and availability of such services. What should be the policies and strategies adopted by the country to promote exports of health services? What kinds of supporting policies and measures are required to ensure that trade in health services is not at the expense of national priorities and the interests of the poor? How can a public-private balance be maintained in the delivery of health services in the wake of increased commercialization of health services? These are all issues that deserve serious consideration if governments are to take due advantage of the emerging global opportunities in health services while also successfully mitigating the adverse effects of such globalization.

This study attempts to answer some of the above questions. It aims at analyzing the impact of international service trade on the development of the health care system, particularly in terms of human resource for health (HRH). The paper also summarizes Thailand's commitments to GATS and discusses their potential impact on national health systems and HRH. It also explores the national mechanisms and strategies undertaken in trade negotiations. Finally, it attempts to synthesize recommendations to strengthen the negotiation capacity and to propose measures to alleviate negative consequences so that the country will benefit from international service trade.

Methods

Literature review

This involved a review of relevant documents on international service trade, such as international service trade agreements (GATS and other regional agreements), Thai laws, research studies and reports concerning international free trade, economic development, health system development and development of human resources for health.

Semi-structured interviews

Twenty experts in various fields, such as experts on HRH, health care systems, health education systems, private health systems, lawyers, civil service commission and representatives of professional councils were interviewed through a semi-structured questionnaire.

Brainstorming sessions

A half-day seminar in which 50 experienced researchers, administrators, trade negotiators and other stakeholders participated was held to seek their additional opinions and recommendations for future development.

Results

Literature review

The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)

Many of the WTO agreements are binding multilateral agreements. GATS, however, which is one of the binding agreements, imposes only general obligations. Members can voluntarily choose to commit, at any level, to any specific mode and sector of services. However, the commitments must conform to the principles of Most Favored Nation (MFN) and National Treatment (NT). The commitment should progressively be increased in the following round of negotiations (progressive liberalization). Governments may modify or withdraw their commitments three years after their entry into force, subject to negotiated compensation. Governments also maintain the ability to introduce regulations in the pursuit of quality and other domestic policy objectives [6].

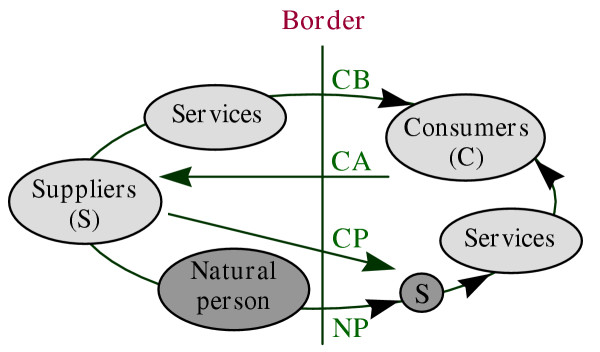

There are four main modes of international trade in services [7] (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Mode of international trade in services [8]

Mode 1: Cross-border supply (CB)

This includes telemedicine, teleconferencing, teleconsultation, tele-education, and subscription to journals and databases on the Internet. This CB has been greatly facilitated through rapid expansion of e-commerce.

Mode 2: Consumption abroad (CA)

This includes travelling abroad, including via health tours, to seek high-technology treatments or cheaper health services

Mode 3: Commercial presence (CP)

This includes foreign investment in hospital operation, medical and dental services and management of health care.

Mode 4: Temporary movement of natural persons (NP)

This includes temporary emigration of doctors from developing to developed countries, and import of specialists from developed countries into facilities invested in by foreign capital in the developing countries.

Of 12 service sectors included in GATS, at least five are directly related to health care systems [8], i.e., the business, distribution, education, finance, and health and social services sectors. The professional services under the business service sector deal with services of health professionals. The distribution service sector relates to services in pharmaceutical retailing. The education service sector involves the training and education of health professionals. The financial sector deals with health insurance and flows of foreign capital for investment in private hospitals. The health and social services sector includes hospital services, medical and dental services, diagnostic services and management of health service facilities.

There are various kinds of barriers to trade in health services [9]. These include entry visas, work permits, professional and premises licenses, investment permits and insurance reimbursement. Commitment to services trade agreements can reduce some or all of these barriers.

Countries' commitment to GATS

Except for the education sector, health has drawn the least commitment among WTO members. Table 1 summarizes the level of commitments on some health-related services [6,10].

Table 1.

WTO Members' commitments on some health-related services (3rd quarter 2000)

| Services | Number of members committed | % of total WTO members |

| Medical and dental | 54 | 39.1 |

| Midwives and nursing | 29 | 20.0 |

| Hospital | 44 | 31.9 |

| Other human health services | 17 | 12.3 |

| Health insurance | 78 | 56.5 |

Note: Many of these commitments, particularly in mode 1, are "unbound", which means no commitment. Sources: Adapted from WHO/WTO, 2002 [6] and Adlung R, Carzaniga A, 2002 [10]

Thailand's commitments to GATS in relation to health

Health is a very sensitive sector, and is usually the last sector in which a country will allow free international trade. The ASEAN Free Trade Agreement on Services, started almost a decade ago, has also not gone very far in terms of trade in health services [11]. In the first round of binding to WTO (1995), Thailand proposed both general (cross industries) and specific national commitments in all sectors except the health and social services sector and other unclassified services sectors [8,11]. Table 2 shows the types of general commitments as well as five service sectors related to health.

Table 2.

Thailand's commitment to GATS in the first round (1995)

| Mode of trace in services | General commitments | Specific sector/subsector commitments | ||||||||||

| Business | Distribution | Education | Financial | Related health and social | ||||||||

| Professional: medical and dental | Retailing (drug dispensaries) | Professional and/or short course education | Life and non-life insurance | Hospital | ||||||||

| MA | NT | MA | NT | MA | NT | MA | NT | MA | NT | MA | NT | |

| 1. Cross-border supply | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | + | U | U | U |

| 2. Consumption abroad | U | U | U | U | U | U | + | + | + | U | U | U |

| 3. Commercial presence | B | U | U | U | U | U | B | + | B | U | U | U |

| 4. Presence of natural persons | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | B | U | U | U |

Source: Ministry of Commerce, Thailand Note: MA= market access commitments and NT= national treatment; Three types of commitments: (+) Full commitment; (B) Commitments with limitations: Bound; (U) No commitment: Unbound.

It is clear that Thailand chose to commit in some sectors and only a few modes of services. For instance, in the commercial presence mode for cross industries' commitment, market access is allowed for companies for which foreign shares account for up to 49%, but no commitment on other modes. There is no limitation for consumption abroad in the education services sector but no commitment for presence of natural persons. The life and non-life insurance business under the financial sector is open to all four modes at different levels of commitment. There are some limitations for commercial presence and presence of natural persons in this sector, but no limitation for cross-border supply and consumption abroad.

It was also found that most of the Thai commitments to GATS are much below those allowed by its legislation. For example, while there is no commitment to mode 4, the Thai Medical Council allows foreign graduates from recognized medical colleges who have Thai residency to enroll in the licensing examination. Passing the licensing examination results in getting a lifetime practice license in Thailand. This practice of under-commitment to GATS definitely allows some flexibility in the future round of negotiations as well as in future amendment of the legislation.

Potential health implications

Mode 1: Cross-border trade

A private hospital in Thailand tested satellite-based telesurgery with a hospital in the USA in 1998. It was successful but not cost-effective. Cross-border trade has been more evident in education services. For example, many Thai students have registered for the master's degree in public health via distance learning with institutions in the UK and USA. So far the success rate has not been very high, however. Empirical information from some medical practitioners reveals that seeking second opinions through teleconsultation via the Internet or direct contact is on the rise. While increasing the accessibility and quality of services, cross-border trade also imposes some threats on the practices of local health professionals.

Since 1995, the Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, has invested in the internal use of satellite-based telemedicine among distant district hospitals and tertiary public hospitals. This was aimed at increasing accessibility to better-quality health care, but due to its high cost and the economic crisis in 1997, only 18 sites were established. The main use was for teleconferencing and tele-education. An extensive evaluation in 1999 found that the system was not cost-effective [12].

In the era of "outsourcing" to reduce cost, there is an increasing trend in this mode of supply, especially in the area of medical records management and radiological services[13]. Some contacts between US hospitals and Thai radiologists have been initiated but not completed. In addition, there are still several ethical, legal and "gatekeeper" management issues to be seriously considered in this mode of trade [14], particularly the issue of "confidentiality of personal information".

Mode 2: Consumption abroad

Consumption of foreign capital

Between 1989 and 1993 the number of private hospitals and beds increased sharply due to increased demand from economic growth. This phase of investment used mainly internal loans and savings. After the opening of the free financial market in 1993, there was a massive influx of low-interest foreign loans. These loans were invested in some industries that later became non-performing loans, including some investments in private hospitals. The occupancy rate of for-profit-private hospitals was around 40% in 1997, a 250% excess of bed supply [15].

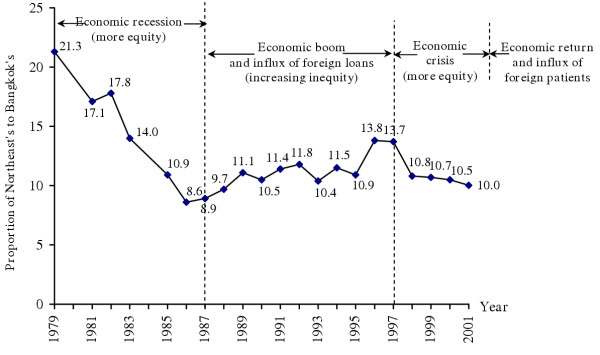

The mushrooming of private hospitals created a big demand for human resources. With income about 5 to 10 times higher in the private sector, the internal migration of rural physicians to urban private hospitals began in the late 1980s. Figure 2 shows that the difference between the ratio of doctors-to-population in Bangkok and the poorest north-eastern region increased from 8.6 times in 1986 to 13.7 times in 1997.

Figure 2.

Proportion of Northeast to Bangkok population-to-doctor ratios, 1979–2001 (Source: Bureau of Health Policy and Plan, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand)

The bed-to-doctor ratio of rural district hospitals increased from 7.1 beds per doctor in 1988 to 15.3 beds per doctor in 1998. In April 1997, a few months before the economic crisis, 21 rural district hospitals functioned without a single full-time physician. This difference decreased after the economic crisis hit Thailand in 1997, however, due to declining demands in the private sector [16].

This internal brain drain was due partly to rapid economic growth as well as the opening of free international financial trade. It is a good example that the opening of trade in services other than health may affect health systems [17].

Consumption of health services

Providing health services for foreign patients creates heavy investment in advanced health technology for the private sector at the expense of public health. This enhances the existing tiered health care system, with shifting of HRH from the rural public to the urban private services, resulting in increasing inequity.

The Thai health care system is attractive to foreign patients due to its high quality and comparatively low price. Since the 1997 economic crisis, the government and the private health sector have started intensive promotion to attract foreign patients; this has been very successful. In the year 2001, the Department of Export Promotion, Ministry of Commerce, carried out a survey of 20 private hospitals that were known to cater foreign patients. The survey found 470,000 foreign patient visits, a 38% increase from 2000, reported by seven hospitals [18]. One of the most popular hospitals had more than 200,000 visits. Countries with the highest number of inflow patients were Japan, USA, Taiwan, UK and Australia. Moreover, there is an increasing trend of patients from the Middle East and other Asian countries. It was estimated that the total 2001 figure could be around 1 million.

Due to its private nature, the resources needed to provide services to one foreigner may be equivalent to those used to provide service to 4–5 Thais. Thus the workload was equivalent to 3–4 million Thai patients. This was equivalent to around 3% of the total workload of the system in 2001. If growth continues at the current rate, the workload for serving foreign patients may go up to 12% of the total workload in 5 years. This means a demand of approximately an additional 4,000 full-time-equivalent doctors for urban private hospitals [19].

Commitments to GATS on the Financial Sector, including the portability of health insurance, may facilitate more inflow of foreign patients. Most countries limit their commitment on portability of public health insurance [10]. Nevertheless, there is evidence of increasing movement towards partial or total payment for services received abroad [20]. Currently the Japanese National Health Insurance system allows reimbursement of up to 70% of health care expenses from foreign providers.

This increase in mode 2 trade in health services, in addition to the recovering economy, resulted in a new round of internal brain drain. The number of annual physician losses as compared to the number of new recruits in the MoPH increased from 4.5% and 7.6% in 2000 and 2001 to 32.2% in 2002 [17].

On the other hand, better-off Thais also go abroad for health services, mainly to the western countries. In the last decade, there was an increasing trend to seek health care from Chinese medicine in China. So far there has not been a study on the size and cost of this consumption abroad.

Mode 3: Commercial presence

Most of the commercial presence occurs through joint ventures of foreign providers and investors with local partners in order to ensure access to qualified local health personnel and a supply of paying patients. Foreign patients (mode 2) and foreign commercial presence (mode 3) in medical education or in hospitals may lead to better-quality health care because of increased availability of sophisticated medical technology. At the same time, it may distort the health care market by enhancing tiered health care systems and internal brain drain. The quality of education or health care in the public sector might suffer due to loss of qualified human resources to the private sector.

There are 13 Thai private hospital chains in the stock market that are open to foreign investment. If the foreign investors' share exceeds 49%, permission must be requested from the Ministry of Commerce. After the 1997 economic crisis, many big private hospital chains went bankrupt and loans they made became non-producing loans (NPL) [16]. Foreign investors started to come in looking for low-priced private hospital stocks. According to the Ministry of Commerce registrar, no private hospital has foreign shares above 49%.

A study in 1999 found only 0.57% foreign share of new investment in private hospitals in Thailand between 1992 and 1998 [14]. The survey conducted by the National Statistical Office in 2001 found that to date there are 24 hospitals nationwide (7.36%) with part-foreign ownership, mainly in Bangkok (Table 3). The countries or region involved and their ownership percentages are: Japan (25%), Singapore (19.4%), China (11.1%), Europe (11.1%) and the USA (5.6%).

Table 3.

Current foreign investment in private hospitals in Thailand

| Location/Region | Without foreign investment | With foreign investment | |||||

| Number | % | Total | Hospital size (beds) | ||||

| <50 | 51–100 | 101–200 | >200 | ||||

| Bangkok | 48 | 77.2 | 14 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Central | 117 | 95.90 | 5 | - | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Northeast | 42 | 93.33 | 3 | - | 3 | - | - |

| North | 59 | 96.71 | 2 | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| South | 36 | 100.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 302 | 92.64 | 24 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 8 |

Source: National Statistical Office in Buddhasri, 2003.

But empirical evidence found that some of the private hospital chains have already been taken over by foreign investors through so-called "nominee" shareholders. These foreign investors brought in more capital and more efficient management and marketing systems. They also brought in more foreign patients. Thus health services may eventually become like other industries, in which foreign investors benefited from high quality but low-cost labour to be more competitive in export-led industries.

Foreign patients receive services from foreign-owned private hospitals. Consequently, the country may be left with the problem of internal brain drain, while the benefit from foreign patients was finally channeled back to investors' countries. In the future, if mode 4, import of health workforce, is also allowed, more foreign professionals may move in to provide services to foreign patients. In the current round of GATS negotiations, which started in early 2003, Taiwan, China and India have asked Thailand to open mode 4 for some cadres of health professionals [21].

Despite Thailand's not having committed to the distribution sector (Table 2), its law allows partial investment. Some foreign pharmaceutical retailing chains, e.g. Boots, started doing business in Thailand a decade ago. Their expansion has started to have negative impacts on local pharmacies.

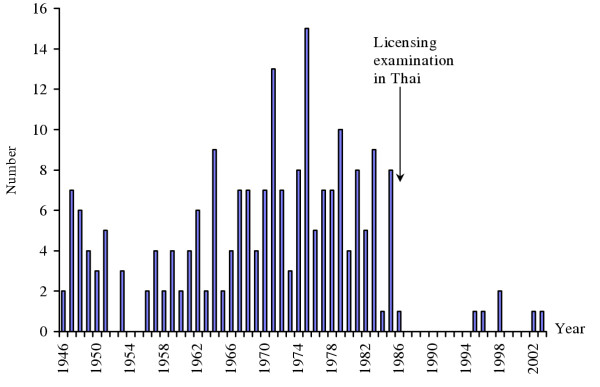

Mode 4: Movement of natural persons

Barriers to movement of health professionals include requirements for a work permit, visa and length of stay, residency, investment conditions and licensing for practice. The Thai Medical Council, the national licensing body for physicians, requires graduation from an accredited medical college and permanent residency for foreigners to be eligible to take the licensing examination [22]. From 1946 to 1986, there were 229 Thai-licensed foreign practitioners. Since 1987, after the examination has been given in Thai, only six foreigners succeeded in acquiring the medical practice license (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Foreign medical practitioners licensed in Thailand, 1946–2003 (Source: Thai Medical Council)

On the other hand, opening the labour market to the increasing demand in rich countries has created external brain drain and shortages of qualified health professionals in developing countries. In 1960 to 1975, approximately 1,500 Thai medical graduates migrated to the USA in response to the opening of the labour market. Since very few of them returned, the country thus permanently lost those physicians. This accounted for 20% of the total 7,500 Thai medical graduates in 1975; in 1965, half of the new medical graduates also emigrated [23].

The reason behind this massive external migration was the increased demand for doctors in the USA due to the Vietnam War and the initiation of publicly subsidized Medicaid and Medicare. In addition, higher income and opportunities for further education and training enhanced the migration. The income of new medical graduates in Thailand in 1970 was around 2,000–2,500 Baht per month, as compared to 30,000–40,000 Baht per month in the USA, a 15- to 16-fold difference.

This external brain drain has no relation to international trade agreements. Without international trade agreements or commitment to GATS, developed countries can open or close their health professional labour market according to their internal demand.

The external brain drain of medical doctors from African countries is another good example. In Ghana, 65% of new medical graduates emigrated within 10 years [24]. While South African doctors migrated to western countries, in 1996 the government imported 300 Cuban doctors to work in the rural health centres [25]. In England, the first NHS plan targets the employment of 20,000 more nurses and midwives in 2004 than in 2000, while the second plan targets 35,000 additional nurses by 2005 compared to 2001 [26]. Nurses from English-speaking African countries, such as South Africa and Zimbabwe, as well as some Asian countries, such as India and the Philippines, poured into the UK. Very few Thai nurses joined in this migration. Opportunities for continuing education and private practice within the country and inadequate proficiency in foreign languages prevent Thai health professionals from working abroad.

Although health personnel may send remittances back to their home country, which are a substantial source of foreign exchange in some countries, such as the Philippines and India, the public sector itself is not directly compensated. If this type of movement increases without an appropriate regulatory framework, the equity, quality and efficiency of the domestic health system will suffer. Due to massive migration of nurses from African countries, an ethical recruitment code for midwives and nurses was developed by the International Confederation of Midwives and International Council of Nurses [27-29].

Countries in the European Community started free movement of all professionals including those in health in 1998. The effects of this agreement on the flow of health professionals need to be followed closely, and can be a good lesson for other regional trade blocs.

Mechanisms of Thailand to deal with the international services trade and GATS

Thailand has set up a national structure and mechanisms in preparation for negotiations with WTO. All stakeholders, including related ministries, civil societies, researchers and the business sector, are involved. In the Ministry of Public Health itself, a policy-level committee was set up in 2000. Three subcommittees were also set up: one on TRIPS, one on GATS and the other on SPS and TBT.

In mid-2000, the committee agreed that commitment on health services should be unbound in all modes of trade except consumption abroad. There were at least two reasons to support this decision. First, before further commitment to GATS, there is a need to strengthen the supporting mechanisms to establish and implement adequate policies and measures. This is to ensure that international health service trade is not at the expense of national priorities and the interests of the poor. Furthermore, there is a need to strike a public-private balance in the wake of increased commercialization of health services.

In 2002, a meeting among all stakeholders agreed that the Thai trade negotiators, the Ministry of Commerce, should try their best to convince developing countries to allow for portability of their public health insurance. If successful, this would bring in more foreign patients and might have serious implications for the Thai health care system. With the new government policy to support more inflow of foreign patients, a Centre to Promote Trade in Health Services was set up in the MoPH.

Expert interviews and brainstorming sessions

Inadequate knowledge and skill among local experts

It was found that not many health experts understood and knew about international trade and WTO in detail. Those who understand WTO agreements have little knowledge of the health care system, particularly of HRH. More than 40 experts, who were identified as potential resource persons, were approached, but only 20 agreed to be interviewed. Most of those who declined to be interviewed explained that they did not have enough understanding and knowledge of either WTO or HRH. After the interview and the brainstorming session, many experts admitted that this research project was a very good learning process for them.

Outcome of interview and brainstorming session

In summary, interviewees and participants reflected their views that the implications of international service trade on HRH components include the following:

HRH planning

• International service trade will create more difficulties for HRH planning because of the high level of complexity and dynamics of demand. However, as the size of the international service trade is still quite small, the HRH plan still depends more on the size of the internal health market.

• Foreign health professionals may not enter to any great extent, due to the Thai-language licensing examination and cultural barriers.

• Strengthening of the HRH planning and management capacity is very important for successful response to the complexity and the dynamics from international service trade.

Education and training

• Language and culture will be the barriers for foreign investment in education and training of HRH.

• Investment in quality educational institutions, which is very capital-intensive, may be a losing proposition in low-income countries.

• If investment in foreign-owned training institutions occurs, they may be more popular than domestic ones due to the greater opportunities for graduates to work domestically and internationally.

Management of HRH

• Internal migration of the health workforce is a bigger problem than external migration. Language proficiency and different culture are barriers to both external migration and the influx of foreign professionals.

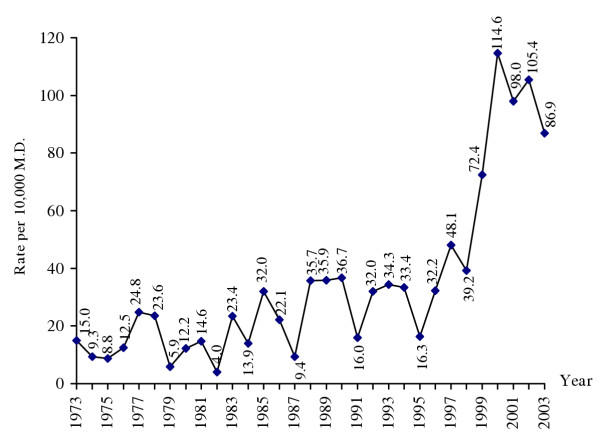

• With more international trade in health services, professional ethics may erode. More malpractice lawsuits can be envisaged if professional councils are not strong enough. The rate of malpractice litigation to the Thai Medical Council has increased sevenfold since 1980, particularly after the 1997 economic crisis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Rate of medical malpractice cases filed with the Thai Medical Council, 1973–2003 Source: Thai Medical Council)

• The regulatory capacity of professional councils and professional associations should be strengthened. Civil society should be involved in controlling, monitoring and accrediting health professionals.

Other suggestions

• A strong and efficient governance mechanism for the national health care system is required to cope with the increasing complexity and dynamics.

Discussion and recommendations

It is clear from the results of this study that international service trade can have significant negative implications on health care systems, particularly HRH. The main implications include internal and external migration of HRH; inequitable tiered health care systems and erosion of professional ethics, with a wider gap between patients and health professionals. Some countries, such as Canada, for example, campaigned for application of Article 1.3 in GATS to exclude health services from GATS negotiation. Article 1.3 (b) states that "services" under GATS includes any service in any sector except services supplied in the exercise of the government. These countries faced enormous pressure from their trade partners, however [30-32]. Some positive implications include influx of foreign currencies and capital, better opportunity for professional training, improving quality of care and access to high technology equipment. For a developing country like Thailand to benefit optimally and be protected from the negative implications of international service trade, the following recommendations should be seriously considered:

Capacity building and research study

• There is a need for a research package on health system and manpower development, and international trade and health systems. Economists, public health experts, legal experts and social scientists should be encouraged to work together in conducting this research. Important research questions that should be urgently studied are:

○ The current situation of trade in health services and its future projection, as well as analysis of the areas of comparative advantage;

○ Implications of international trade in health services on the health care sector, including on HRH;

○ Policy recommendations to enhance positive implications and alleviate negative implications;

○ Foreign investment in health services;

○ Capacity of Thailand in investment in health services.

• National capacity of HRH management and research must be rapidly strengthened.

• Academic institutions should develop training courses covering international trade issues, especially trade agreements under the WTO and their impact on health systems.

• Countries, WHO and international donors should support fellowships for manpower development in this area.

Strengthening national mechanisms for trade negotiation

• The national intersectoral mechanisms for the development of national positions for trade negotiation are a crucial component. The mechanisms should be continuously strengthened and used.

• The Ministry of Public Health should have a permanent body responsible for international trade policy and health systems, with high-calibre technical officers trained in these areas.

Prevention of future negative impacts

A clear national health system reform policy is essential to protect the system from negative implications. Health system reform should be implemented vigorously, especially in the areas of development of capacity to supervise and regulate private facilities, to manage an equitable and efficient health insurance system, in health care system planning and management, and in HRH development. A commission on HRH development should be established with strong secretariat support, preferably under the National Health Systems Reform Committee. The commission would provide continuous wisdom for strategic management of HRH.

In principle, further commitments should be considered only when there are requests from WTO members. Positive and negative impacts should be seriously considered in detail before expanding the commitment to GATS, especially if the commitments are beyond the current national legislative framework. All stakeholders or affected agencies should also be consulted.

Encouraging the health service system to benefit from free trade in services

• Both the public and private sectors should collaboratively prepare a clear proposal focused on expansion of international services trade in member countries based on health wisdom such as traditional massage and traditional medicine. This proposal can be used to negotiate with other member countries.

• Encouraging public health facilities, particularly those in rural areas, to take part in providing health services for foreigners in order to allow more financial incentives and reduce repeated internal brain drain.

Conclusion

It is clear that international trade is growing rapidly. Trade in services is growing faster than trade in goods. International trade in health services is also growing fast, despite that few countries commit seriously to health services trade under GATS. The growing international trade in health services has created several negative implications for health care systems. It promotes commercialization of health care and enhances the existing tiered health care systems. It stimulates external and internal migration of health workforces, both of which result in increasing inequity of health care access. It also enhances the erosion of ethics among health professionals, resulting in an increase in malpractice litigation. In this increasingly complex and dynamic situation, developing countries require strong national mechanisms with adequate capacity to effectively govern their health care systems. This is to ensure that the poor will not be deprived of access to essential health services.

Competing interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This paper is adapted from research sponsored by the World Health Organization Thailand Country Office.

Contributor Information

Suwit Wibulpolprasert, Email: suwit@health.moph.go.th.

Cha-aim Pachanee, Email: chaaim@health.moph.go.th.

Siriwan Pitayarangsarit, Email: siriwan@hsri.or.th.

Pintusorn Hempisut, Email: yolk@health.moph.go.th.

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Statistics Brief, Paris. 2001.

- National Income Account of Thailand 1995–2002 http://www.nesdb.go.th/econSocial/macro/NAD.htm#ni

- Chanda R. Trade in Health Services Working Paper NoWG4. Geneva: World Health Organization, Commission on Macroeconomics and Health; http://www.cmhealth.org/docs/wg4_paper5.pdf 5 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization Statistics on Globalization Geneva. 2001.

- Woodward D, Drager N, Beaglehole R, Lipson D. Globalization, global public goods, and health. In: Vieira C, Drager N, editor. In Trade in Health Services: Global, Regional and Country Perspectives. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2002. pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and World Trade Organization WTO Agreements and Public Health Geneva. 2002.

- Usha V. The GATS and International Trade in Health Services in the South East Asia Region. Delhi: WHO/SEARO. 1999.

- Wibulpolprasert S, Jindawatthana A, Hempisut P. General agreements on trade in services and its possible implications on the development of human resources for health. A paper presented in the Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association (APHA) Boston. 2000.

- Wibulpolprasert S, Pitayarangsarit S. Implications of GATS and medical practices in Thailand. Nonthaburi: Thai Medical Council; 1999. mimeograph in Thai. [Google Scholar]

- Adlung R, Carzaniga A. Health services under the General Agreement on Trade in Services. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2001;79:352–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Multilateral Trade Negotiations, Department of Business Economics WTO's free trade in health services. In Round Table Seminar on Free Trade in Health Services Le Meridian Hotel Bangkok. 1999.

- Chooprapawan C. Evaluation of the Tele-medicine System of the Thai Ministry of Public Health. Bangkok: Ministry of Public Health; 1999. mimeograph in Thai. [Google Scholar]

- New York Times Who's reading your x-ray? http://www.nytimes.com/2003/11/16/business/yourmoney/16hosp.html?ex=1070723077&ei=1&en=55c1c86b5adc9c79 16 November 2003.

- Janjaroen WS, Supakankunti S. International trade in health services in the millennium: the case of Thailand. In: Vieira C, Drager N, editor. In Trade in Health Services: Global, Regional, and Country Perspectives. Vol. 87. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2002. p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health . Thailand Health Profile 1999–2000. Bangkok: the Veterans Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wibulpolprasert S, Sirikanokwilai N. Situation and Solutions for the Shortage and Maldistribution of Doctors in Thailand A Research Report. Nonthaburi: Thai Medical Council; 1997. in Thai. [Google Scholar]

- Wibulpolprasert S, Pengpaiboon P. Integrated strategies to tackle inequitable distribution of doctors in Thailand: four decades of experience. Human Resources for Health. 2003;1:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Export Promotion, Ministry of Commerce Questionnaire Survey of Foreign Patients. 2002. mimeograph.

- National Health System Reform Office, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand Proposal for Sustainable Human Resources for Health Development. 2003. mimeograph in Thai.

- Pollock AM, Price D. The public health implications of world trade negotiations on the general agreement on trade in services and public services. Lancet. 2003;362:1072–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachanee C, Wibulpolprasert S. Trade in health services and GATS: A case of Thailand. Paper presented at the Workshop on Trade in Health Services: Building Capacity in Developing Countries, at Ottawa University, Ottawa, Canada. 9–11 July 2003.

- Thai Medical Council . The Medical Profession Act, 1982. Bangkok: Thai Medical Council; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wibulpolprasert S. Inequitable distribution of doctors: Can it be solved? Human Resources for Health Development Journal (HRDJ) 1999;1:2–39. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovlo D, Nyonator F. Migration by graduates of the University of Ghana Medical School: A preliminary rapid appraisal. Human Resources for Health Development Journal (HRDJ) 1999;1:40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Health Systems Trust and the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation . South African Health Re-view. Durban: Fishwick Printers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Buchan J, Seccombe I. More Nurses, Working Differently? A Review of the UK Nursing Labour Market 2002–2003. London: Royal College of Nursing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Secretariat Commonwealth Code of Practice for International Recruitment of Health Workers Geneva: Commonwealth Secretariat. 2002.

- The International Confederation of Midwives Ethical Recruitment of Midwives. http://www.internationalmidwives.org/Statements/Ethical%20recruitment%20of%20midwives.pdf

- The International Council of Nurses Position Statement-Ethical Nurse Recruitment. http://www.icn.ch/psrecruit01.htm

- Schwartz B. NAFTA reservations in the areas of health care. Health Law Journal. 1997;5:99–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S. GATS: How the World Trade Organization's New "Services" Negotiations Threaten Democracy. Ottawa: Canada Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sanger M. Reckless Abandon: Canada, the GATS and the Future of Health Care. Ottawa: Canada Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2001. [Google Scholar]