Abstract

Background

Although obesity is associated with risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD) and improved survival, less is known about the associations of obesity with risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) and post-AKI mortality.

Methods

In a single-center inception cohort of almost 15,000 critically ill patients, we evaluated the association of obesity with AKI and AKI severity, as well as in-hospital and one-year survival. AKI was defined using the Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative criteria.

Results

The AKI incidence rates for normal, overweight, Class I, II, and III Obesity were 18.6, 20.6, 22.5, 24.3 and 24.0 percent respectively, and the adjusted odds ratios of AKI were 1.18 [95% CI 1.06–1.31], 1.35 [1.19–1.53], 1.47 [1.25–1.73], 1.59 [1.31–1.87], compared to normal weight, respectively. Each 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index (BMI) was associated with a 10% risk [95% CI 1.06–1.24; p<0.001] of more severe AKI. Within-hospital and one-year survival rates associated with the AKI episodes were similar across BMI categories. In conclusion, obesity is a risk factor for AKI injury, which is associated with increased short- and long-term mortality.

Keywords: obesity, body mass index, acute renal failure, acute kidney injury, survival

Introduction

As obesity grows as an epidemic, knowledge of its pathophysiologic complications is important. Many of the hallmark systemic abnormalities of obesity, including insulin resistance, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, are known contributors to renal disease, and more recently, renal-specific pathways, including increased autophagy and fibrosis, have been described (1). In addition, the emerging importance of renal vein congestion as a determinant of renal function (2) raises questions whether the hemodynamic complications of obesity, including obesity hypoventilation, pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale, may contribute to renal dysfunction.

Although obesity has been associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (3–6), it is not widely accepted as a risk factor for acute kidney injury (AKI) (7, 8). The incidence of AKI in obesity has been described in bariatric surgery (9, 10), cardiac surgery (11–14), and in the acute respiratory distress syndrome (15), and a more recent study focused on severe AKI requiring dialysis (16). However, to our knowledge, the association of BMI with AKI and AKI severity has not been well described in a large representative critically ill population. In addition, no study has described the long term outcomes of AKI in critically ill obese patients. In CKD, obesity is paradoxically associated with an improved prognosis (17, 18). Thus, whereas an episode of AKI is typically associated with worse survival (19, 20), whether this association is also true for critically ill obese patients is unknown.

To address the simultaneous associations of obesity with incidence and prognosis of AKI, we evaluated a large cohort of patients hospitalized in the intensive-care units (ICU) of a single large medical center.

Methods

Study Population

We used the MIMIC-III (Multiparameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care) database, a joint venture managed by the Laboratory for Computational Physiology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the Department of Medicine at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) (21). MIMIC-III contains data from 37,305 unique adult critical care admissions between 2001 and 2012 at BIDMC, a 700-bed urban academic medical center with 77 adult ICU beds. The database contains high-temporal-resolution data from clinical systems, including lab results, electronic documentation, and bedside monitor trends and waveforms. Use of the MIMIC II database has been approved by the Institutional Review Boards of BIDMC and MIT.

A total of 22,073 individuals had a documented height within the BIDMC electronic medical record. Of these, 18,938 had a documented weight upon ICU admission, allowing calculation of body mass index (BMI). After exclusion of 743 ESRD patients, 17,140 had documentation of renal function. To identify comorbidities and medication exposure, we included the 15,470 patients with an admission history and physical examination with admission medication lists. Of these, 484 were missing documentation of admission ICU vitals, leaving a primary complete case analysis of 14,986.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was acute kidney injury during ICU admission, as defined by either a ≥0.3 mg/dL increase within 48 hours or a ≥50 percent increase within 7 days of ICU admission, or acute dialysis, in keeping with the Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines (22). We also explored the association of BMI with severity of AKI. Stage I AKI was defined as 50 to 100% increase in admission serum creatinine within 7 days, Stage II as greater than 100% to 200% increase, and Stage III as greater than 200% increase, or the initiation of acute dialysis. Following best practice guidelines, we used the admission creatinine to define “baseline”. (23)

To evaluate risk of death during hospitalization and within one year from hospital discharge, we linked medical records to the Social Security Death Index.

Exposure

BMI was the primary exposure, categorized in standard World Health Organization groupings: <18.5 (underweight), ≥18.5 to <25 (normal), ≥25 to <30 (overweight), ≥30 to <35 (Class I obesity), ≥35 to <40 (Class II obesity), and BMI≥40 (Class III obesity), and as a continuous variable per 5 units of BMI.

Because weight at the time of critical illness might not reflect usual body weight, we performed a validation study among 150 randomly selected subjects within the dataset to determine body weights measurements obtained during noncritical illness. A total of 86 individuals had documented weights during noncritical illness in the electronic medical record. The Spearman correlation coefficient between ICU and non-ICU body weights measurements was 0.93 (p<0.001), with a median difference of −0.03 kg (interquartile range −2.8 to 2.9).

Covariates

Demographic information included age, sex, and race, coded as white, African-American, Asian, Hispanic, other, or unknown. We identified heart failure patients through Natural Language Processing (NLP) searching of the Past Medical History section of the admission examination or Elixhauser discharge coding (24). We also used oral diabetes medication or insulin usage, along with Elixhauser discharge coding, to identify diabetic patients. All additional Elixhauser discharge coding comorbidities except for “acute renal failure” and “obesity” were included as separate variables (24). ICU types included cardiac, surgical, cardiothoracic, and medical units. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores were used to indicate severity of illness. Because of the effect of hemodynamics on renal function, we also included systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and temperature as independent variables. Admission creatinine, defined as the first available creatinine 24 hours prior to, or six hours after, ICU admission, was used as a determinant of “baseline” kidney function. Admission hemoglobin was also included. Because obesity is likely associated with increased diuretic, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I), angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB), and statin usage, we used NLP searches of pre-hospital medication lists to identify these exposures. All admission values, except for creatinine, were taken from the first available laboratory data within twenty four hours of ICU admission.

Statistical Analysis

We present descriptive baseline characteristics stratified by BMI. We used logistic regression to examine the association between BMI, defined categorically and continuously, and odds of AKI, based on serum creatinine changes. We adjusted for age, gender, race, ICU type, SOFA score, history of diabetes, congestive heart failure, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease and 22 additional Elixhauser comorbidities, admission systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, creatinine and hemoglobin, and pre-illness diuretic, ACE-I, ARB, or statin use.

We describe the incidence of AKI stages I to III per BMI classification. We used ordinal logistic regression to describe the adjusted risk of a one-step increase of AKI severity with an increase of BMI. In separate logistic regressions, we then examined the risk of having either Stage II or III AKI compared to either no AKI or Stage I AKI, and the risk Stage III AKI, compared to no AKI, Stage I, or Stage II AKI.

To contextualize the clinical significance of an episode of AKI in obesity, we used logistic regression to define the adjusted risk of an episode of AKI on within-hospital mortality within each BMI category. We also describe the effect of AKI on long term survival according to BMI in hospital survivors. We used Cox regression analyses, censoring those who survived 365 days or more, and adjusting for the same variables as above, within each BMI category.

In sensitivity analyses, to further explore potential mechanisms for the observed strong association of increasing BMI with risk of AKI, we performed sequential logistic regressions examining how the addition of admission proteinuria, defined as trace or greater on urinary dipstick measurement, and admission central venous pressure, obtained within the first six hours of admission, changed the association of BMI with AKI. In addition, we used creatinine measurements obtained prior to seven days from ICU admission as “baseline” in 7000 patients with available measurements.

For all analyses, normal weight was considered the reference category. All analyses were performed using JMP Pro (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of 14986 critically ill patients admitted to a medical or surgical intensive care unit with available data, 431 (3%) were underweight, 4271 (28%) were normal weight, 5047 (34%) were overweight, 2908 (19%) had class I obesity, 1292 (9%) had class II obesity, and 1037 (7%) had class III obesity. Obesity was associated with a higher prevalence of heart failure, hypertension and diabetes than those with normal BMIs, and greater exposure to diuretics, ACE-Is, ARBs, and statins prior to admission (Table I). Admission blood pressure tended to be similar across BMI categories. Admission creatinines tended to be higher in obese patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by BMI categories

| <18.5 | ≥18.5 to <25 | 25 ≥ to <30 | 30 ≥ to <35 | 35 ≥ to <40 | >40 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 431 | n = 4271 | n = 5047 | n = 2908 | n = 1292 | n=1037 | ||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, mean (SD), yrs | 66.42 (17.4) | 66.0 (17.8) | 65.2 (15.9) | 63.9 (14.5) | 62.3 (13.6) | 58.1 (13.9) | <0.001 |

| Female, no. (%) | 273 (63.3) | 1972 (46.2) | 1783 (35.3) | 1091 (37.5) | 582 (5.1) | 578 (55.7) | <0.001 |

| Race, no. (%) | |||||||

| White | 308(71.38) | 3078 (72.1) | 3693 (73.7) | 2080 (71.5) | 952(73.7) | 724 (69.8) | <0.001 |

| Black | 8 (8.8) | 308 (7.2) | 336 (6.7) | 239 (8.2) | 117(9.1) | 123 (11.9) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (1.6) | 108 (2.5) | 177 (3.5) | 116 (4.0) | 49 (3.8) | 49 (3.8) | |

| Asian | 28 (6.5) | 183(4.3) | 107 (2.1) | 24 (0.8) | 7 (0.5) | 7 (0.5) | |

| Other | 12 (2.8) | 121 (2.8) | 129 (2.6) | 90 (3.1) | 37 (2.9) | 26 (2.5) | |

| Unknown | 38 (8.8) | 473 (11.1) | 605 (120.) | 359 (12.4) | 130 (10.1) | 123 (11.9) | |

| Cardiac Care Unit | 67 (15.5) | 808 (18.9) | 945 (19.1) | 555 (19.1) | 261 (20.2) | 184 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| Medical Care Unit | 187 (43.4) | 1416 (33.2) | 1464 (29.0) | 842 (29.0) | 402 (31.1) | 378 (36.5) | <0.001 |

| Surgical Care Unit | 177 (41.1) | 2047 (48.0) | 2638 (52.2) | 1511 (52.0) | 629(48.6) | 475 (45.8) | <0.001 |

| Past Medical History, no. (%) | |||||||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 46(10.7) | 407 (9.5) | 460 (9.1) | 256 (8.8) | 155 (12.0) | 142 (13.7) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 48(11.1) | 445(10.4) | 524 (10.4) | 256 (8.8) | 130 (10.1) | 90 (7.7) | 0.24 |

| Hypertension | 133 (30.9) | 1461(34.2) | 1983(39.2) | 1240 (42.6) | 579 (44.8) | 442 (42.6) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 111 (25.8) | 785 (18.4) | 765 (15.2) | 512 (17.6) | 287(22.2) | 282 (27.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 64 (14.9) | 921 (21.6) | 1381 (27.4) | 1071 (36.8) | 591(45.7) | 467 (45.3) | <0.001 |

| Diuretic Use | 97 (22.5) | 1183 (27.7) | 1484 (29.4) | 1011 (34.8) | 511 (39.6) | 460 (44.4) | <0.001 |

| Ang. Conv. Inhibitor Use | 93 (21.6) | 1049 (24.6) | 1444 (28.7) | 919 (31.7) | 401 (31.1) | 336 (32.4) | <0.001 |

| Ang. Receptor Blocker Use | 23 (5.3) | 269 (6.3) | 438 (8.7) | 299 (10.3) | 152 (11.8) | 108 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| Admission Vitals, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 123.7 (26.9) | 123.2 (24.8) | 123.1 (24.2) | 12336 (14.5) | 124.0 (24.4) | 124.4(24.6) | 0.55 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 64.6 (17.9) | 63.1 (15.6) | 63.8 (15.7) | 64.1 (15.8) | 64.6 (15.4) | 64.8 (17.0) | 0.002 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 89.8 (19.9) | 88.3 (19.2) | 87.1 (18.8) | 87.3(18.7) | 88.8 (19.1) | 91.0 (19.4) | <0.001 |

| Temperature, degrees °C | 36.3 (1.2) | 36.4 (1.0) | 36.5 (0.9 | 36.5 (0.9) | 36.6 (1.0) | 36.7 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Admission Values, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Hemaglobin, % | 11.2 (2.1) | 11.7 (2.1) | 12.0 (2.2) | 12.2 (2.2) | 12.0 (2.2) | 11.8 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.3) | <0.001 |

Mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and number (within column percentages) for categorical variables provided. P values across groups provided.

BMI and incidence and severity of AKI

During the course of critical illness, 3122 (21.1%) individuals developed AKI. As seen in Table II, the incidence and adjusted risk of AKI progressively increased with higher BMI. Each 5 kg/m2 increment in admission BMI was associated with a 10% [95%CI 1.06–1.24; p<0.001] higher adjusted risk of AKI in a model that accounted for demographics, comorbidities, severity of critical illness, medication exposure, and admission creatinine. As a frame of reference, diabetes was associated with a 1.26 [95% CI 1.15–1.38; p<0.001] higher risk of AKI.

Table II.

Adjusted risk of AKI according to BMI

| BMI Categories | Per five kg/m2 positive |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI <18.5 | 18.5≥BMI<25 | 25≥ BMI<30 | 30 ≥BMI<35 | 30 ≥BMI<35 | BMI ≥ 45 | - | |

| N(%) | 69(16.0) | 796(18.6) | 1041(20.6) | 653(22.5) | 314(24.3) | 249(24.0) | |

| OR 95%CI p value |

0.81 (0.60–1.06) p=0.13 |

Ref. | 1.18 (1.06–1.31) p=0.003 |

1.35 (1.19–1.53) p<0.001 |

1.47 (1.25–1.73) p<0.001 |

1.59 (1.31–1.87) p<0.001 |

1.10 (1.06–1.24) p<0.001 |

Number of AKI episodes per BMI category, within column percentages, and odds ratio provided. Adjusted for age, gender, race, ICU type, SOFA, history of diabetes, congestive heart failure, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease and 22 additional Elixhauser comorbidities, admission vitals (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, temperature) admission labs (hemoglobin, creatinine) and pre-illness medication usage (ACE-I, ARB, statin and diuretics).

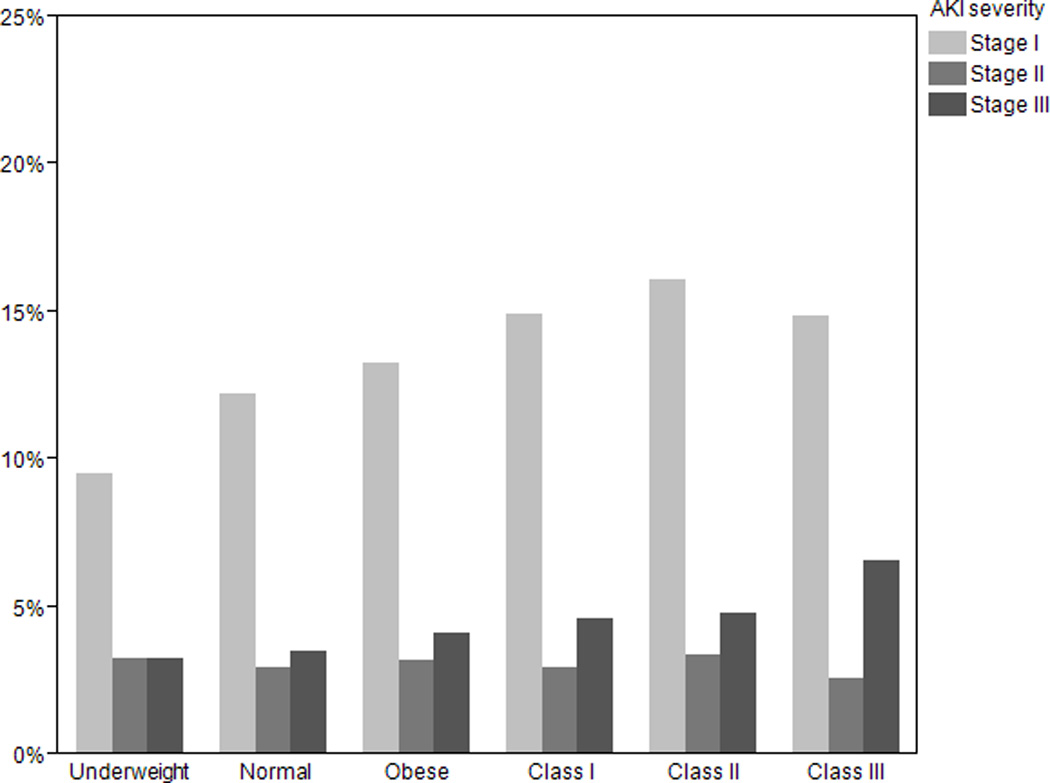

The incidence of AKI severity according to BMI is illustrated in Figure 1. In adjusted analysis, a 5 kg/m2 increment was associated with a 9% higher risk [95% CI 1.06–1.22; p<0.001] of having a higher stage of AKI. As seen in table III, the risk of having Stage II or III AKI, compared to either no AKI or stage I AKI, or Stage III AKI, compared to no AKI, stage I, or stage II AKI, increased progressively with higher BMI relative to normal weight patients.

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients stratified by BMI who develop Stage I, II, and III AKI within seven days of ICU admission.

Table III.

Adjusted association of BMI with AKI severity

| BMI Categories | Per five kg/m2 positive |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <18.5 | ≥18.5 to 25 Ref. |

≥25 to 30 | ≥30 to 35 | ≥30 to 35 | ≥ 40 | - | |

| AKI as defined by KDOQI Stage II or Stage III (n=1092) | |||||||

| OR 95%CI p value |

0.94 (0.66–1.41) p=0.78 |

Ref. | 1.23 (1.04–1.47) p=0.01 |

1.26 (1.04–1.54) p=0.02 |

1.22 (0.94–1.55) p=0.12 |

1.38 (1.06–1.80) p=0.02 |

1.06 (1.02–1.10) p=0.006 |

| AKI as defined by KDOQI Stage III (n=636) | |||||||

| OR 95%CI p value |

0.91 (0.48–1.60) p=0.77 |

Ref. | 1.29 (1.03–1.62) p=0.03 |

1.44 (1.11–1.87) p=0.005 |

1.23 (0.87–1.75) p=0.22 |

1.75 (1.25–2.42) p<0.001 |

1.08 (1.04–1.14) p=0.007 |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, ICU type, SOFA, history of diabetes, congestive heart failure, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease and 22 additional Elixhauser comorbidities, admission vitals (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, temperature) admission labs (hemoglobin, creatinine) and pre-illness medication usage (ACE-I, ARB, statin and diuretics). KDOQI (Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative).

AKI and survival

There were 1513 (10%) deaths during the critical illness hospitalization. The association of AKI with in-hospital mortality was modified by BMI (multiplicative interaction term p<0.01). When stratified by BMI category, AKI was consistently associated with a significantly higher risk of death (Table IV). When stratified by AKI, a protective effect of obesity on hospital survival was observed in those without AKI, as has previously been reported. A 5 kg/m2 BMI increase was associated with a 0.89 [95% CI 0.85–0.94; p<0.001] odds ratio of within-hospital death in those without AKI. However, in those with AKI, each 5 kg/m2 BMI increase was associated with a 0.98 [95% CI 0.96–1.09; p=0.59] risk of within-hospital death.

Table IV.

Association of AKI episode with short and long term mortality according to BMI status

| BMI Categories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <18.5 | ≥18.5 to 25 | ≥25 to 30 | ≥30 to 35 | ≥30 to 35 | ≥ 40 | |

| Within hospital mortality | ||||||

| OR 95%CI p value |

1.31 (0.55–2.98) p=0.53 |

2.09 (1.66–2.62) p<0.001 |

2.13 (1.69–2.86) p<0.001 |

2.85 (2.08–3.92) p<0.001 |

4.26 (2.65–6.89) p<0.001 |

2.04 (1.21–3.42) p=0.008 |

| One year mortality in hospital survivors | ||||||

| OR 95%CI p value |

0.51 (−0.73–0.03) p=0.07 |

1.29 (1.05–1.59) p=0.02 |

1.16 (0.92–1.45) p=0.19 |

2.85 (2.08–3.92) p<0.001 |

1.37 (0.76–2.42) p=0.28 |

2.51 (1.18–5.76) p=0.02 |

Odds ratio (95%CI) are provided for effect of AKI episode on outcome per BMI category. Reference is those without AKI within each category. Adjusted for age, gender, race, ICU type, SOFA, history of diabetes, congestive heart failure, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease and 22 additional Elixhauser comorbidities, admission vitals (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, temperature) admission labs (hemoglobin, creatinine) and pre-illness medication usage (ACE-I, ARB, statin and diuretics) and BMI.

Amongst 13,473 hospital survivors, 1568 (12%) died within one year of hospital discharge. The association of AKI with subsequent one-year mortality was not modified by BMI (multiplicative interaction term= 0.43). Similarly, an episode of AKI during critical illness was associated an increased risk of dying within the following one year across BMI categories (Table IV).

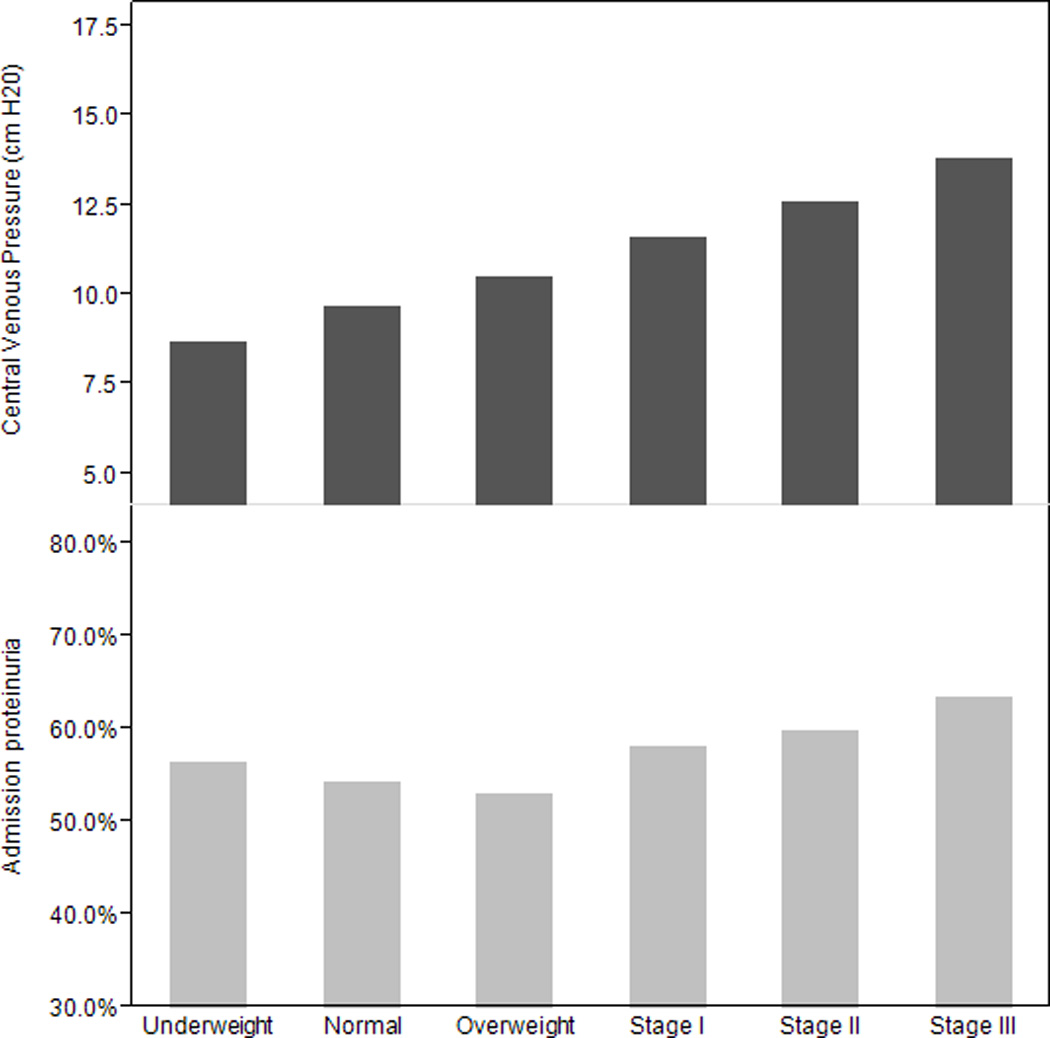

Sensitivity analyses

Among patients with available data, CVP (n=4017) and prevalence of admission proteinuria (n=5753) increased progressively with higher BMI (Figure 2). Addition of CVP into the multivariate adjusted model reduced the odds ratio minimally (OR1.08, 95%CI 1.02–1.14; p=0.003], per 5 kg/m2 BMI increase), and in 2116 participant with both measurements, each 5 kg/m2 increment was associated with a 1.08 [95% CI 1.01–1.16; p=0.03] increased risk of AKI. Defining baseline renal function by a serum creatinine obtained more than seven days prior to critical illness, rather than by the admission creatinine, did not meaningfully change the association between BMI and AKI. In 7891 patients with available pre-illness serum creatinine measurements, the correlation between pre-illness and admission serum creatinine measurements was 0.68 (p<0.001). Each 5 kg/m2 increment remained associated with a 1.08 [95% CI 1.01–1.16; p=0.02] increased risk of AKI.

Figure 2.

Mean admission central venous pressure and percentage of patients with admission proteinuria stratified by BMI.

Discussion

Our findings highlight obesity as a risk factor for AKI during critical illness. In models that adjusted for comorbidities, acuity of illness, pre-illness ACE, ARB, and diuretic use, each 5 kg/m2 was associated with a ten percent increased risk of AKI. Furthermore, these episodes of AKI were associated with worse short and long term survival.

Our findings supplement a growing awareness of the susceptibility to AKI in obesity. In a recent study of almost 500 critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress, each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI was associated with a 20% increased risk of AKI (15). In a large Austrian study, severely obese patients had a greater than 2 fold increased risk of severe AKI than normal weighted patients (16). Long term survival was not available in either study. More recent studies, however, have not identified obesity as a significant risk factor for AKI (7).

Our observed association between obesity and AKI raise questions about potential pathophysiologic mechanisms (25). The hemodynamic perturbations associated with obesity could explain an increased susceptibility (26). Cor pulmonale, a result of hypoventilation, sleep apnea, and pulmonary hypertension, occurs frequently in obesity (27, 28), and leads to sodium avidity and peripheral venous congestion. Obese patients have higher right sided filling pressures (29) and greater diuretic requirements (30) than those with normal weight. The role of venous congestion as a determinant of renal function has been known for over 80 years, with early physiology experiments highlighting that increased renal venous pressures decreased urine formation (31, 32). More recent clinical data has focused on peripheral venous congestion in heart failure (33), where CVPs, but not cardiac output or pulmonary capillary wedge pressures, are associated with renal dysfunction, highlighting the importance of the trans-renal pressure gradient, a balance between renal arterial perfusion and venous drainage, as a determinant of renal function. Similarly, increasing CVP has been associated with AKI in sepsis (34).

In our analysis, increasing BMI was associated with higher CVPs obtained within six hours to the ICU. However, inclusion of CVP measures did not significantly attenuate nor modify the association between BMI and AKI, suggesting additional factors may exist.

Recent data has highlighted organ-specific abnormalities in obesity, with changes seen both within the kidney and the heart. Obesity leads to renal glomerular hypertrophy and hyperfiltration (35) which potentially contribute to renal susceptibility. More recently, an “adipose-renal” hormonal axis has emerged. Adiponectin, an insulin sensitizing hormone that regulates glucose and lipid metabolism, and which is markedly decreased in visceral obesity, is protective in some models of renal ischemia reperfusion injury, although considered pathogenic in others (36). Leptin, an adipocyte derived cytokine that is metabolized in the kidney and controls energy metabolism and appetite, modulates susceptibility to endotoxin-mediated renal failure and stimulates proliferation and fibrosis (37, 38). Autophagy, an important internal degradation system whereby cells can removed damaged proteins and organelles, is impaired in obesity (1). Cardiac changes associated with obesity also might affect renal perfusion. In addition to increased left ventricular hypertrophy, direct infiltration of the myocardium has been reported, termed “cardiomyopathy of obesity” (39–41). Thus, whether kidney or cardiac specific changes associated with obesity contribute to the incidence of AKI is plausible.

In addition to establishing obesity as a risk for AKI, our data highlights the associated short- and long-term outcomes associated with AKI. In our analysis, even though obese patients were more likely to develop AKI, these AKI episodes were not less significant. Rather, across BMI categories, AKI was associated with increased within-hospital mortality and one-year mortality. In addition, whereas obesity has paradoxically been associated with an improved prognosis in critical illness, this protective association is absent in patients with AKI. Whether renal protective strategies, including minimizing radiographic contrast and potentially nephrotoxic medications, careful use of diuretics, and careful blood pressure management to minimize hypotension, might improve outcomes, remains speculative.

Limitations

Although our study had a number of strengths, including an extremely large dataset with ample power and systematic assessment of mortality, the observational nature of our analysis limits any conclusions of causality. Furthermore, although the large number of patients and the multiple covariates allow for adjustment, it is plausible that confounding remains. Given the unaccounted effect of critical illness on weight, and the lack of information about weight changes prior to admission, confounding due to malnutrition, cachexia, and fluid retention likely remains, although we would not expect non-adipose contributors to BMI such as fluid retention to be associated with improved one-year mortality. In addition, our manual review of randomly selected charts suggests a strong correlation between critical and non-critical illness BMI values. In addition, we used admission serum creatinines to account for baseline function, which likely leads to misclassification. However, in a subset of patients with available creatinine measurements prior to critical illness, admission and baseline creatinines were highly correlated, and the association of BMI with AKI remained robust. Furthermore, because the baseline serum creatinine may be increased in obesity, our outcome of a relative change in creatinine should be conservative and hence this would bias our findings towards the null.

Conclusions

Obese patients are more likely to develop AKI, which is associated with increased short and long term mortality. Whether renal protective strategies during critical illness might improve outcomes will require further investigation.

Acknowledgements

Funding:

Dr. Celi’s work in the Laboratory for Computational Physiology at MIT is funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering under NIBIB Grant 2R01 EB001659. Dr. Danziger is supported by a Normon S. Coplon Extramural Grant from Satellite Healthcare. Dr. Feng is supported by Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) Graduate Scholarship. This work is supported by NIH grant R01 EB001659.

Dr. Feng received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and disclosed work for hire. Dr. Mark received support for article research from the NIH. His institution received funding from the NIH. Dr. Celi received support for article research from the NIH. Dr. Mukamal received support for article research from the NIH.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- ACE I

angiotensin converter enzyme inhibitor

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- SOFA

sequential organ failure assessment

- KDOQI

Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The contributing authors declare that there was no conflict of interest.

Copyright form disclosures: The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest

Study concept and design: Danziger

Acquisition of data: Chen, Lee, Feng, Celi, Mark,

Analysis and interpretation of data: Danziger, Mukamal

Drafting of the manuscript: Danziger, Mukamal

Study supervision: Danziger, Mukamal

Overall study responsibility: Danziger, Mukamal

No author acknowledges any conflict of interest with the content of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Yamahara K, Kume S, Koya D, Tanaka Y, Morita Y, Chin-Kanasaki M, et al. Obesity-Mediated Autophagy Insufficiency Exacerbates Proteinuria-induced Tubulointerstitial Lesions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damman K, van Deursen VM, Navis G, Voors AA, van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL. Increased central venous pressure is associated with impaired renal function and mortality in a broad spectrum of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(7):582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ting SM, Nair H, Ching I, Taheri S, Dasgupta I. Overweight, obesity and chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;112(3):c121–c127. doi: 10.1159/000214206. discussion c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ix JH, Sharma K. Mechanisms linking obesity, chronic kidney disease, and fatty liver disease: the roles of fetuin-A, adiponectin, and AMPK. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(3):406–412. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009080820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Othman M, Kawar B, El Nahas AM. Influence of obesity on progression of non-diabetic chronic kidney disease: a retrospective cohort study. Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;113(1):c16–c23. doi: 10.1159/000228071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Iribarren C, Darbinian J, Go AS. Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(1):21–28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane-Gill SL, Sileanu FE, Murugan R, Trietley GS, Handler SM, Kellum JA. Risk factors for acute kidney injury in older adults with critical illness: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(6):860–869. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sileanu FE, Murugan R, Lucko N, Clermont G, Kane-Gill SL, Handler SM, et al. AKI in low-risk versus high-risk patients in intensive care. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):187–196. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03200314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCullough PA, Gallagher MJ, Dejong AT, Sandberg KR, Trivax JE, Alexander D, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and short-term complications after bariatric surgery. Chest. 2006;130(2):517–525. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma SK, McCauley J, Cottam D, Mattar SG, Holover S, Dallal R, et al. Acute changes in renal function after laparoscopic gastric surgery for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2(3):389–392. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar AB, Bridget Zimmerman M, Suneja M. Obesity and Post-Cardiopulmonary Bypass-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013 doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wigfield CH, Lindsey JD, Munoz A, Chopra PS, Edwards NM, Love RB. Is extreme obesity a risk factor for cardiac surgery? An analysis of patients with a BMI > or = 40. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29(4):434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yap CH, Mohajeri M, Yii M. Obesity and early complications after cardiac surgery. Med J Aust. 2007;186(7):350–354. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billings FTt, Pretorius M, Schildcrout JS, Mercaldo ND, Byrne JG, Ikizler TA, et al. Obesity and oxidative stress predict AKI after cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(7):1221–1228. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011090940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soto GJ, Frank AJ, Christiani DC, Gong MN. Body mass index and acute kidney injury in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(9):2601–2608. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182591ed9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Druml W, Metnitz B, Schaden E, Bauer P, Metnitz PG. Impact of body mass on incidence and prognosis of acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(7):1221–1228. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Abbott KC, Salahudeen AK, Kilpatrick RD, Horwich TB. Survival advantages of obesity in dialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(3):543–554. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Anker SD, Coats AJ, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Obesity paradox as a component of reverse epidemiology in heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(15):1797. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1797-a. author reply -8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoste EA, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury: epidemiology and diagnostic criteria. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12(6):531–537. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3280102af7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, Venkataraman R, Angus DC, De Bacquer D, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R73. doi: 10.1186/cc4915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeed M, Villarroel M, Reisner AT, Clifford G, Lehman LW, Moody G, et al. Multiparameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care II: a public-access intensive care unit database. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(5):952–960. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a92c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palevsky PM, Liu KD, Brophy PD, Chawla LS, Parikh CR, Thakar CV, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(5):649–672. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.02.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ad-hoc working group of E. Fliser D, Laville M, Covic A, Fouque D, Vanholder R, et al. A European Renal Best Practice (ERBP) position statement on the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guidelines on acute kidney injury: part 1: definitions, conservative management and contrast-induced nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(12):4263–4272. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wickman C, Kramer H. Obesity and kidney disease: potential mechanisms. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33(1):14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chagnac A, Weinstein T, Korzets A, Ramadan E, Hirsch J, Gafter U. Glomerular hemodynamics in severe obesity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278(5):F817–F822. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.5.F817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marik PE, Desai H. The emergent malignant obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a new critical care syndrome. Author reply. J Intensive Care Med. 2013;28(3):200. doi: 10.1177/0885066612464343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marik PE, Desai H. Characteristics of patients with the "malignant obesity hypoventilation syndrome" admitted to an ICU. J Intensive Care Med. 2013;28(2):124–130. doi: 10.1177/0885066612444261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishman AP, Maxwell MH, Crowder CH, Morales P. Kidney function in cor pulmonale; particular consideration of changes in renal hemodynamics and sodium excretion during variation in level of oxygenation. Circulation. 1951;3(5):703–721. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.3.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Louw EJ, Sun PO, Lee J, Feng M, Mark RG, Celi LA, et al. Increased incidence of diuretic use in critically ill obese patients. J Crit Care. 2015;30(3):619–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winton FR. The influence of venous pressure on the isolated mammalian kidney. J Physiol. 1931;72(1):49–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1931.sp002761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winton FR. The influence of increase of ureter pressure on the isolated mammalian kidney. J Physiol. 1931;71(4):381–390. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1931.sp002743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, Sokos G, Taylor DO, Starling RC, et al. Importance of venous congestion for worsening of renal function in advanced decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(7):589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Legrand M, Dupuis C, Simon C, Gayat E, Mateo J, Lukaszewicz AC, et al. Association between systemic hemodynamics and septic acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a retrospective observational study. Crit Care. 2013;17(6):R278. doi: 10.1186/cc13133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chagnac A, Weinstein T, Herman M, Hirsh J, Gafter U, Ori Y. The effects of weight loss on renal function in patients with severe obesity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(6):1480–1486. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000068462.38661.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng CF, Lian WS, Chen SH, Lai PF, Li HF, Lan YF, et al. Protective effects of adiponectin against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury via prostacyclin-PPARalpha-heme oxygenase-1 signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227(1):239–249. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han DC, Isono M, Chen S, Casaretto A, Hong SW, Wolf G, et al. Leptin stimulates type I collagen production in db/db mesangial cells: glucose uptake and TGF-beta type II receptor expression. Kidney Int. 2001;59(4):1315–1323. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590041315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolf G, Hamann A, Han DC, Helmchen U, Thaiss F, Ziyadeh FN, et al. Leptin stimulates proliferation and TGF-beta expression in renal glomerular endothelial cells: potential role in glomerulosclerosis [seecomments] Kidney Int. 1999;56(3):860–872. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexander JK. The cardiomyopathy of obesity. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;27(5):325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(85)80002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasper EK, Hruban RH, Baughman KL. Cardiomyopathy of obesity: a clinicopathologic evaluation of 43 obese patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(9):921–924. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90739-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGavock JM, Victor RG, Unger RH, Szczepaniak LS American College of P, the American Physiological S. Adiposity of the heart, revisited. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(7):517–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]