Abstract

Objectives

To determine the effect of alendronate (ALN) on inflammatory markers and osteoprotegerin (OPG)/receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL), and to explore the associations of baseline systemic inflammation and vitamin D status on the bone mineral density (BMD) response to ALN.

Methods

82 HIV+ patients with lumbar spine T-score ≤−1.5 were randomized to ALN 70 mg weekly or placebo for 48 weeks; all received calcium carbonate 500 mg/vitamin D3 200 IU twice daily. Serum C-telopeptide (CTx) and BMD were assessed at baseline and week 48. Stored plasma samples in 70 subjects were assayed for 25-hydroxyvitamin D level (25(OH)D), OPG, RANKL, IL-6, and soluble receptors for TNF-α 1 & 2 (sTNFR 1 & 2).

Results

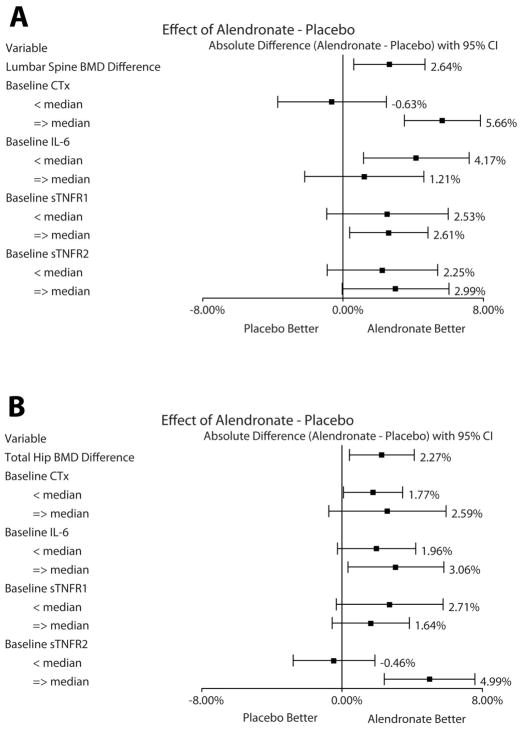

ALN increased BMD more than placebo at both the lumbar spine (difference ALN-placebo=2.64%; p=0.011) and the total hip (difference=2.27%; p=0.016). No within- or between-arm differences in OPG, RANKL, or inflammatory markers were observed over 48 weeks. High baseline CTx and sTNFR2 were associated with a more robust BMD response to ALN over 48 weeks at the lumbar spine (difference=5.66%; 95% CI 3.50, 7.82; p<0.0001) and total hip (difference=4.99%; 95% CI 2.40, 7.57; p=0.0002), respectively. Baseline 25(OH)D<32 ng/ml was associated with larger increases in total hip BMD over 48 weeks, independent of ALN treatment (p=0.014).

Conclusions

Among HIV+ patients, higher baseline bone resorption and TNF-α activity were associated with an increased BMD response to alendronate. The greater BMD response in those with lower vitamin D reinforces the importance of vitamin D supplementation with bisphosphonate treatment.

Keywords: low bone mineral density, alendronate, bone turnover marker, inflammation, vitamin D

INTRODUCTION

Low bone mineral density (BMD) is common in HIV-infected patients with the estimated prevalence of osteoporosis, defined as a T-score ≤−2.5, more than 3-fold greater than HIV-seronegative controls (1), leading to a higher than expected risk of fractures in HIV-infected populations (2). As the HIV-infected population ages, fragility fractures are expected to increase in frequency, thereby contributing to morbidity and mortality.

In HIV-infected patients with low BMD, bisphosphonates have been shown to improve bone mineral density (4,5). Changes in bone density explain only a small part of the reduction in fracture risk with bisphosphonates. Bisphosphonates bind to bone, decrease osteoclast activity, and are considered primarily anti-resorptive agents; however, both bone resorption and bone formation are affected by bisphosphonate treatment and additional mechanisms may play a role. One such pathway may be the osteoprotegerin (OPG)/receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB (RANK)/RANK ligand (RANKL) system. Normally, osteoblasts express RANKL, which interacts with RANK, found on the cell surface of osteoclast precursors, thereby inducing osteoclast differentiation and proliferation. As a control mechanism, osteoblasts also secrete OPG, which binds to RANKL and prevents osteoclast activation. The ratio of OPG/RANKL has been used in clinical studies as a parameter to measure balance in the OPG/RANK/RANKL system, and its dysregulation is implicated in pathogenesis of low bone density in HIV-infected patients (7,8). In other populations, OPG concentrations have been shown to increase with bisphosphonate therapy and are correlated with changes in bone mineral density (9,10). These findings suggest that osteoblastic secretion of OPG may be stimulated by bisphosphonates, thus increasing the ratio of OPG/RANKL. Another potential mechanism of action of bisphosphonates is the effect on inflammation. Inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and TNF-α, are potent stimulators of osteoclast activity and have been implicated in the uncoupled bone resorption seen in some patients with osteoporosis (11,12). In HIV-infected patients, inflammation has been linked to reduced BMD and increased bone resorption (7,13). In postmenopausal women, bisphosphonate therapy has also been associated with reductions in inflammatory cytokines (14).

Bisphosphonate effects may be also influenced by other factors. In the general population, greater increases in BMD and larger decreases in fracture risk have been observed in those who have the most rapid bone turnover (15,16). Similarly, adequate vitamin D status is also important to augment the salutary effects of bisphosphonates (17). Whether suboptimal vitamin D status and heightened systemic inflammation, both highly prevalent in HIV infection, would modify the response to bisphosphonates is not known.

The study objectives were to use ACTG A5163: 1) to determine the effect of alendronate on OPG/RANKL and selected inflammatory markers, and 2) to explore the association of systemic inflammation, vitamin D status, and other baseline factors on the BMD response to alendronate.

METHODS

Study Population

ACTG A5163 was a 48-week, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded clinical trial designed to evaluate the effect of alendronate + calcium/vitamin D3 vs. placebo + calcium/vitamin D3 in HIV-infected persons with low BMD (6). The eligibility criteria have been previously reported (6). Briefly, HIV-infected men and women, 25 years or older with a lumbar spine T-score ≤−1.5 were eligible for recruitment. Subjects were required to be receiving stable antiretroviral therapy (ART) for at least 12 weeks and have a plasma HIV-1-RNA level of 5000 copies/ml or less and a CD4 cell count of 100 cells/ml or greater. Persons with an untreated cause of secondary osteoporosis were excluded (hypogonadism, hyperthyroidism, vitamin D deficiency (25(OH)D <15 ng/ml), hyperparathyroidism (defined as a parathyroid hormone level >80 pg/ml), renal disease (defined as a creatinine clearance <50 ml/min), chronic use of systemic corticosteroid therapy, recent use of anabolic steroids, history of cancer requiring systemic chemotherapy, or Paget’s disease). Persons with a history of treatment for osteoporosis, recent fracture, hepatitis C virus infection, severe alcohol-related liver disease, history of severe esophageal reflux, or esophagitis or any condition predisposing to esophageal inflammation were also excluded.

Of the 82 randomized subjects, 76 were included in the primary analysis (of the excluded subjects, 4 prematurely discontinued the study, one missed the 48 week visit, and one had unevaluable DXA data). Of these 76 subjects, 70 had stored plasma available at baseline and week 48, and 69 subjects had stored plasma at week 24. The institutional review board of each site approved the study protocol and each subject provided written informed consent, including the use of stored samples for future testing.

Treatment

Subjects were randomly assigned in a double-blinded manner in a 1:1 ratio to receive 70 mg alendronate (ALN) or matching placebo weekly. Randomization was stratified by CD4 cell count at screening (100–200 cells/ml or >200 cells/ml). All subjects received calcium and vitamin D in co-formulated tablets (as calcium carbonate 500 mg/vitamin D3 200 IU tablet) twice a day.

Study Evaluations

At baseline, subjects completed standardized questionnaires on ART use, and current smoking and alcohol use, and, for women, gynecological history. Laboratory analysis included 25(OH)D. BMD measurements of the lumbar spine and left hip were obtained at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in the anteroposterior view (using Hologic or Lunar scanners) using standardized procedures. Scans were read centrally (Body Composition Analysis Center, Tufts University, Boston, MA) by personnel blinded to treatment assignment.

Laboratory Methods

The bone resorption marker, C-telopeptide (CTx), was measured on serum collected from subjects in the fasting state at baseline and at weeks 24 and 48. Serum samples were stored at −70°C for batched testing at the end of the study. Serum CTx ([beta]-CrossLaps; Roche Diagnostic Systems, Inc., Branchburg, New Jersey, USA) was determined by sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay at Quest Diagnostics laboratories. The within-assay coefficient of variation for serum CTx was 0.5–2.2% and the between-assay coefficient of variation was 2.9–4.2%.

OPG, RANKL, sTNFR1, sTNFR2, and IL-6 at baseline, 24 weeks, and 48 weeks were measured using a commercially available multiplex enzyme-labeled immunosorbent sandwich assay system (Aushon Biosystems, Billerica, MA). Tests were done in duplicate and averaged. The median intra-assay coefficients of variation for OPG, RANKL, sTNFR1, sTNFR2, and IL-6 were 5.6%, 6.0%, 8.6%, 11.7%, and 6.9%, respectively. The median inter-assay coefficients of variation for each assay were 8.2%, 12.6%, 6.0%, 10.4%, and 4.5%, respectively.

Statistical Methods

The primary endpoints were the treatment differences in percentage change in OPG, RANKL, and inflammatory markers. Assuming 70 stored specimens, 10% lost specimens, and a conservative Pitman efficiency of 0.864 in the event the marker data had a skewed distribution, there was an effective sample size of 28 per arm. Using a standard two-sided 0.05-level t-test approximation with an assumed SD of 3% and 80% power, we had the ability to detect at least a 2.3% difference in the change in a single marker between the two treatment arms.

The primary analysis was conducted using two-sample Wilcoxon tests to assess whether the percentage changes in OPG, RANKL, and inflammatory markers over 24 and 48 weeks were different between treatment arms. Simple linear regression was used to find factors that were associated with BMD response to ALN over 48 weeks. The response variable was the percentage change from baseline to week 48 in BMD (lumbar spine and total hip separately). The baseline covariates considered were treatment arm (ALN vs. placebo), age (years), race (white vs. non-white; black vs. non-black), sex, body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), HIV-RNA viral load (>400 vs. ≤400 copies/ml), CD4 cell count (cells/ml), 25(OH) D (<32 vs. ≥32 ng/ml), and OPG, RANKL, and inflammatory markers. The baseline covariates found to be associated (p≤0.15) with BMD in univariable analysis were placed in multivariable linear regression models. The final multivariable models contained covariates associated (p<0.10) with BMD after adjusting for age, race, sex, and BMI.

One-sample Wilcoxon tests assessed percentage changes from baseline within treatment arms. Subgroup analyses investigated whether baseline levels of CTx and inflammatory markers were associated with BMD response to ALN over 48 weeks. After dichotomizing baseline CTx and inflammatory markers at their respective medians, the mean difference (ALN-placebo) in percentage change in BMD was calculated. Forest plots were used to summarize the mean differences with 95% confidence intervals for each subgroup, using Wald tests to assess differences. Linear regression models of percentage change from baseline to week 48 in BMD (lumbar spine and total hip separately) were used to formally examine the subgroup analyses by evaluating the interactions between ALN and the dichotomized baseline CTx and inflammatory markers. The analysis was based on the intention-to-treat principle, conducted using SAS version 9.1, and all statistical tests were two-sided.

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The baseline characteristics of the 70 subjects (36 randomized to ALN and 34 to placebo) included in this analysis did not differ from the 12 randomized subjects from whom complete data were not available, except for alcohol use (9/70 (13%) with ≥5 drinks/week vs. 5/12 (42%); Wilcoxon p=0.01) and tenofovir use (30/70 (43%); vs. 1/12 (8%); Fisher’s exact p=0.03). The subjects were 69% male and 67% white, with a median (Q1–Q3) age of 48 (41–54) years at study entry. Baseline demographic characteristics, HIV disease and treatment-related variables, and smoking and alcohol use were similar between treatment groups. The median (Q1–Q3) screening lumbar spine T-scores was −2.1 (−2.5-(−1.8)), with 19 (27%) ≤−2.5. The median (Q1–Q3) baseline lumbar spine and total hip BMD was 0.88 g/cm2 (0.83–0.97) and 0.84 g/cm2 (0.77–0.93), respectively. Baseline BMD and serum concentrations of CTx, OPG, RANKL, and inflammatory markers were similar between treatment groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Arm

| Characteristic | Total (N=70) | Placebo (N=34) | Alendronate (N=36) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 48 (41, 54) | 47 (40, 55) | 48 (44, 54) |

| Race/Ethnicity | White Non-Hispanic | 47 (67%) | 24 (71%) | 23 (64%) |

| Black Non-Hispanic | 12 (17%) | 5 (15%) | 7 (19%) | |

| Hispanic (Regardless of Race) | 6 (9%) | 5 (15%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Sex | Male | 48 (69%) | 23 (68%) | 25 (69%) |

| Menopausal Status | N | 22 | 11 | 11 |

| Post-menopausal | 12 (17%) | 6 (18%) | 6 (17%) | |

| Smoking Status | Ever | 43 (61%) | 21 (62%) | 22 (61%) |

| Alcohol (drinks/week) | None | 24 (34%) | 15 (44%) | 9 (25%) |

| Infrequent (i.e., < 2/month) | 10 (14%) | 3 (9%) | 7 (19%) | |

| 0.5–4 | 27 (39%) | 10 (29%) | 17 (47%) | |

| 5–30 | 9 (13%) | 6 (18%) | 3 (8%) | |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | N | 69 | 33 | 36 |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 24 (22, 26) | 24 (23, 27) | 24 (22, 26) | |

| Screening CD4+ Count (cells/mm3) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 463 (324, 679) | 441 (356, 638) | 479 (311, 683) |

| > 200 | 67 (96%) | 33 (97%) | 34 (94%) | |

| HIV-1 RNA (copies/ml) | ≤ 400 | 64 (91%) | 31 (91%) | 33 (92%) |

| Antiretroviral Drug Class | NRTI | 70 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 36 (100%) |

| NNRTI | 22 (31%) | 16 (47%) | 6 (17%) | |

| PI | 46 (66%) | 21 (62%) | 25 (69%) | |

| Fusion Inhibitor | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | |

| Tenofovir Use | Any | 30 (43%) | 14 (41%) | 16 (44%) |

| 25 OH D (ng/ml) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 33 (22, 42) | 35.00 (26.50, 43.00) | 32 (21, 41) |

| < 32 | 33 (47%) | 15 (44%) | 18 (50%) | |

| Screening Lumbar Spine T-Score | Median (Q1, Q3) | −2.10 (−2.50, −1.80) | −2.00 (−2.30, −1.70) | −2.15 (−2.55, −1.80) |

| ≤ −2.5 | 19 (27%) | 8 (24%) | 11 (31%) | |

| Lumbar Spine BMD (g/cm2) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.88 (0.83, 0.97) | 0.90 (0.83, 0.98) | 0.88 (0.82, 0.95) |

| Total Hip BMD (g/cm2) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.84 (0.77, 0.93) | 0.83 (0.78, 0.95) | 0.84 (0.76, 0.91) |

| CTx (pg/ml) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 408 (263, 583) | 402 (263, 603) | 416 (267, 526) |

| OPG (pg/ml) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 4.26 (3.30, 5.44) | 4.53 (3.45, 5.55) | 4.08 (2.91, 5.34) |

| RANKL (pg/ml) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.00 (0.46, 1.81) | 1.00 (0.43, 2.79) | 0.86 (0.47, 1.44) |

| OPG/RANKL | Median (Q1, Q3) | 4.37 (1.93, 10.59) | 5.18 (1.33, 10.59) | 4.20 (2.13, 11.10) |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.49 (1.86, 4.21) | 2.95 (2.25, 7.42) | 2.16 (1.58, 3.68) |

| sTNFR1 (pg/ml) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 1,019 (804, 1,290) | 1,036 (785, 1,313) | 989 (817, 1,221) |

| sTNFR2 (pg/ml) | Median (Q1, Q3) | 742 (519, 1,150) | 649 (519, 887) | 893 (526, 1,308) |

Effect of Alendronate on OPG, RANKL, and Inflammatory Cytokines

The percentage changes in OPG, RANKL, and inflammatory cytokines from baseline to week 24 and to week 48 are summarized in Table 2. The percentage changes over time in OPG, RANKL, IL-6, sTNFR1 and sTNFR2 were not different than zero within treatment arms (Wilcoxon p>0.05) and there were no differences between arms (Wilcoxon p>0.05). For OPG/RANKL, the percentage change over 24 weeks was significantly greater than zero within the placebo arm (Wilcoxon p<0.05), but there were no differences between treatment arms at both time points (Wilcoxon p>0.05).

Table 2.

Percentage change from baseline by treatment arm

| Total (n = 70) | Placebo (n = 34) | Alendronate (n = 36) | Total (n = 70) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar spine BMD | n* | 68 (70) | 33 (34) | 35 (36) | 68 (70) | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 24 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.38 (−0.43, 5.71) | 1.29 (−0.50, 4.63)† | 4.11 (0.50, 6.22)† | 0.482§ | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 48 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 3.09 (−0.71, 6.17) | 1.55 (−1.01, 3.54)† | 4.59 (0.27, 7.49)† | 0.013§ | |

| Total hip BMD | n* | 68 (70) | 33 (34) | 35 (36) | ||

| Percentage change from baseline to week 24 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.64 (0.06, 2.97) | 1.39 (−0.24, 2.42)† | 2.12 (0.17, 4.03)† | 0.067§ | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 48 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.54 (0.25, 4.05) | 1.38 (−0.21, 3.37)† | 3.34 (0.81, 6.24)† | 0.018§ | |

| CTx | n* | 67 (68) | 33 (33) | 34 (35) | ||

| Percentage change from baseline to week 24 | Median (Q1, Q3) | −54.50 (−80.30, −25.60) | −29.80 (−43.70, −17.40)╪ | −79.90 (−87.00, −60.40)╪ | <.001¶ | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 48 | Median (Q1, Q3) | −60.75 (−78.95, −20.70) | −21.80 (−49.00, 5.40) | −76.00 (−82.70, −65.80)╪ | <.001¶ | |

| OPG | n* | 69 (70) | 34 (34) | 35 (36) | ||

| Percentage change from baseline to week 24 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 5.89 (−12.61, 40.36) | 8.21 (−8.74, 35.00) | 5.88 (−14.27, 47.56) | 0.976¶ | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 48 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.07 (−19.91, 35.74) | 2.01 (−16.21, 39.64) | −3.90 (−23.82, 23.86) | 0.617¶ | |

| RANKL | n* | 69 (70) | 34 (34) | 35 (36) | ||

| Percentage change from baseline to week 24 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.00 (−32.94, 41.41) | −6.63 (−41.44, 47.08) | 5.75 (−29.24, 41.41) | 0.316¶ | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 48 | Median (Q1, Q3) | −0.19 (−48.44, 44.55) | −2.78 (−52.82, 75.74) | 0.00 (−22.89, 41.08) | 0.810¶ | |

| OPG/RANKL | n* | 69 (70) | 34 (34) | 35 (36) | ||

| Percentage change from baseline to week 24 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 9.33 (−32.30, 83.68) | 18.01 (−27.13, 104.53)╪ | 2.68 (−34.66, 46.78) | 0.277¶ | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 48 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 10.64 (−38.21, 72.52) | 22.42 (−41.84, 91.29) | 6.31 (−37.91, 40.03) | 0.738¶ | |

| IL-6 | n* | 69 (70) | 34 (34) | 35 (36) | ||

| Percentage change from baseline to week 24 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 4.69 (−24.34, 42.26) | −5.64 (−49.51, 43.03) | 6.21 (−14.37, 42.26) | 0.081¶ | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 48 | Median (Q1, Q3) | −5.56 (−32.52, 41.80) | −18.68 (−40.84, 58.12) | 7.75 (−16.61, 36.70) | 0.111¶ | |

| sTNFR1 | n* | 69 (70) | 34 (34) | 35 (36) | ||

| Percentage change from baseline to week 24 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 5.25 (−12.91, 21.70) | 3.85 (−19.12, 23.37) | 8.46 (−7.92, 21.16) | 0.529¶ | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 48 | Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.77 (−16.36, 30.02) | −3.63 (−16.36, 33.53) | 6.20 (−14.57, 28.05) | 0.828¶ | |

| sTNFR2 | n* | 69 (70) | 34 (34) | 35 (36) | ||

| Percentage change from baseline to week 24 | Median (Q1, Q3) | −1.32 (−23.57, 40.41) | 4.51 (−14.91, 44.68) | −7.10 (−26.97, 28.38) | 0.219¶ | |

| Percentage change from baseline to week 48 | Median (Q1, Q3) | −11.68 (−26.97, 40.53) | −12.73 (−31.86, 40.53) | −5.37 (−24.96, 42.01) | 0.747¶ |

n is for the percentage change from baseline to week 24 and (n) is for the percentage change from baseline to week 48.

Within-arm changes were statistically different from zero (t-test: P<0.05).

Within-arm changes were statistically different from zero (Wilcoxon test: P<0.05).

t-test.

Wilcoxon test.

BMD, bone mineral density; CTx, C-telopeptide; IL-6, interleukin-6; OPG, osteoprotegerin; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand; sTNFR, soluble receptor for tumour necrosis factor.

Baseline CTx and Inflammatory Cytokines and the Bone Mineral Density Response to Alendronate

Subgroup analyses investigated whether baseline levels of CTx and inflammatory cytokines influenced the response to ALN on percentage changes in lumbar spine and total hip BMD from baseline to week 48. As shown in Figure 1A, the overall mean difference (ALN - placebo) in percentage changes in lumbar spine BMD between the arms was 2.64% (95% CI 0.61, 4.67; p=0.011). We found that those who had the highest baseline CTx levels (top 50%) had the most robust response to ALN on percentage change in lumbar spine BMD, with a difference of 5.66% (95% CI 3.50, 7.82; p<0.0001). In a regression analysis, there was an interaction between ALN and CTx; having a baseline CTx level above median (i.e., 408 pg/ml in this study) and taking ALN was associated with a greater increase in lumbar spine BMD over 48 weeks (estimate=6.29%; 95% CI 2.58, 10.00; interaction p=0.001). Associations between baseline levels of IL-6, sTNFR1, or sTNFR2 and lumbar spine BMD response to ALN were not detected.

Figure 1.

The overall mean difference in total hip BMD between the ALN and placebo arms was 2.27% (95% CI 0.42, 4.12; p=0.016; Figure 1B. Those who had the highest baseline sTNFR2 levels experienced the most robust effect of ALN on total hip BMD, with a mean difference of 4.99% (95% CI 2.40, 7.57; p=0.0002). In a regression analysis, there was an interaction between ALN and sTNFR2; having a baseline sTNFR2 level above median (i.e., 742 pg/ml in this study) and taking ALN was associated with a greater increase in total hip BMD over 48 weeks (estimate=5.45%; 95% CI 1.88, 9.02; interaction p=0.003).

Sensitivity analyses evaluated the above significant findings with further subgroup analyses within those with osteoporosis at screening (n=19/70) and within those with osteopenia (n=51/70) (defined as lumbar spine T-score ≤−2.5 and >−2.5, respectively). The direction and magnitude of the changes yielded similar results.

Factors Associated with the Change in Bone Mineral Density over 48 Weeks

Univariable linear regression was utilized to explore factors associated with the percentage change in lumbar spine and total hip BMD from baseline to week 48, with ALN, 25(OH) D, and black race associated with lumbar spine and with ALN, 25(OH) D, black race, and baseline sTNFR2 associated with total hip (Table 3). The multivariable linear regression models are also summarized in Table 3. After adjusting for baseline age, black race, sex, and baseline BMI, only ALN was associated with percent change in lumbar spine BMD over 48 weeks (2.80% increase; 90% CI 1.11, 4.48; p=0.007). When examining total hip BMD and adjusting for baseline age, black race, sex, and baseline BMI, ALN use (2.23% increase; 90% CI 0.77, 3.69; p=0.013) and 25(OH) D <32 ng/ml (2.35% increase; 90% CI 0.71, 3.98; p=0.020) were associated with percent change in total hip BMD over 48 weeks.

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Percentage Change from Baseline to Week 48 in BMD

| Covariate | Unadjusted Univariable Models* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar Spine BMD | Total Hip BMD | |||||

| β | 90% CI | P-Value | β | 90% CI | P-Value | |

| Alendronate vs. Placebo | 2.64% | (0.92%, 4.36%) | 0.013 | 2.27% | (0.71%, 3.83%) | 0.018 |

| 25-OH D (<32 vs. ≥32 ng/ml) | −1.71% | (−3.48%, 0.06%) | 0.112 | 2.51% | (0.97%, 4.06%) | 0.008 |

| Age (per 10 years) | −0.56% | (−1.60%, 0.49%) | 0.38 | −0.07% | (−1.02%, 0.87%) | 0.896 |

| Black Race vs. Non-Black | −3.09% | (−5.40%, −0.79%) | 0.028 | 3.04% | (0.97%, 5.10%) | 0.017 |

| Male Sex vs. Female | 0.48% | (−1.46%, 2.41%) | 0.683 | −2.75% | (−4.41%, −1.09%) | 0.007 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | −0.20% | (−0.42%, 0.03%) | 0.147 | 0.18% | (−0.02%, 0.39%) | 0.146 |

| Covariate | Adjusted Multivariable Models** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar Spine BMD | Total Hip BMD | |||||

| β | 90% CI | P-Value | β | 90% CI | P-Value | |

| Alendronate vs. Placebo | 2.80% | (1.11%, 4.48%) | 0.007 | 2.23% | (0.77%, 3.69%) | 0.013 |

| 25-OH D (<32 vs. ≥32 ng/ml) | (−) | (−) | (−) | 2.35% | (0.71%, 3.98%) | 0.020 |

Univariable models reported only for those covariates with p≤0.15 or included in the multivariable models.

Multivariable linear regression models were adjusted for baseline age, race, sex, and baseline BMI.

Sensitivity analyses evaluated the final lumbar spine and total hip BMD multivariable models after restricting the study population to (1) those with baseline HIV RNA ≤400 copies/ml (n=64/70) and (2) those with baseline HIV RNA ≤400 copies/ml and baseline CD4 count >200 cells/mm3 (n=61/70). In the HIV RNA and CD4 restricted population, 25(OH) D was no longer associated with percent change in total hip BMD over 48 weeks. In addition, there was no evidence of an effect of 25(OH) D <32 ng/ml on changes in OPG, RANKL, and inflammatory cytokines from baseline to week 48.

DISCUSSION

In this secondary analysis of a multicenter, randomized placebo-controlled trial of alendronate in HIV-infected persons with low BMD, we found that alendronate use was not associated with changes in OPG, RANKL, or inflammatory markers although it is possible that our sample size was too small to detect differences between the arm given the higher than expected standard deviations in the change of these analytes over the study interval. We did find, however, similar to the non-HIV+ population, that those subjects with higher baseline bone resorption had a more robust BMD response to alendronate at the spine and those with higher baseline sTNFR2 had a more robust BMD response to alendronate at the hip. Furthermore, low vitamin D levels at baseline were independently associated with increases in hip BMD over 48 weeks. Our findings may have implications for the treatment of HIV-infected persons with low BMD initiating treatment with bisphosphonates.

Bisphosphonates reduce fracture by 40–60% in the general population and are first-line options for the treatment of osteoporosis in the HIV-infected patients (4–6). These medications are thought to have their effect by decreasing the osteoclast function, thereby slowing bone resorption. Other mechanisms may also contribute to their fracture reduction effect. In a randomized trial in post-menopausal women, bisphosphonate treatment over 12 months was associated with a 9% increase in OPG, which correlated with increases in BMD, but RANKL concentrations remained unchanged (9). These results suggest that in addition to their effect on osteoclasts, bisphosphonates may result in increased OPG production, thus possibly stimulating bone formation. Bisphosphonates may also reduce fracture risk by decreasing systemic inflammation. Higher concentrations of inflammatory markers have been associated with bone loss and fracture in the general population (18,19). In a cohort of patients with chronic idiopathic neutropenia, a condition associated with increased TNF-α concentrations and bone loss, bisphosphonate treatment was associated with marked decreases in TNF-α and IL-1β, which correlated with decreases in bone resorption markers and increased in BMD (20).

Contrary to these observations, however, we did not find evidence that alendronate treatment altered concentrations of OPG, RANKL, or any of the inflammatory markers investigated. The OPG/RANKL system appears to be altered in HIV-infected patients and concentrations of both of these analytes decrease with antiretroviral initiation (8,21). These findings suggest that the source of OPG and RANKL in HIV infection may not be limited to osteoblasts or osteocytes, but may also derive from immune cells, such as B cells, which also express these cytokines. It is possible that the source of OPG and RANKL may be important in the determination of alendronate’s effect on these markers or that systemic concentrations of these markers may not reflect concentrations in the bone microenvironment. Other possible explanations include decreasing inflammation with ART treatment may decrease production of OPG and RANKL by the osteoblast or osteocytes; decreases in these variables following initiation of antiretroviral therapy may be an indirect effect. Similarly, although most evidence suggests that markers of systemic inflammation are higher than expected in HIV-infected persons, our lack of association between alendronate treatment and systemic inflammation may be due to differences in the sources and regulation of these markers in HIV infection, compared to chronic idiopathic neutropenia.

We did, however, find that markers of bone resorption at baseline were associated with a greater BMD response to alendronate. Those with the highest concentration of CTx had the greatest increases in lumbar spine BMD with alendronate. This effect has also been observed in bisphosphonate trials in the general population (22,23). Potentially, bone turnover markers could be utilized to identify a subset of patients who might particularly benefit from bisphosphonate treatment (15,24,25). This may be particularly true in HIV-infected persons, in whom antiretroviral therapy increases markers of bone turnover (26), which are generally elevated compared to HIV-uninfected controls (27,28). The clinical use of these markers, however, has been limited by measurement variability making their application to an individual patient difficult (24,25).

Our results show that high baseline sTNFR2 was associated with a greater increase in hip BMD with alendronate treatment. TNF-α is potent stimulator of osteoclast activity and has been implicated in the uncoupled bone resorption seen in some patients with osteoporosis (11,12). The TNF- family has diverse effects on the pathogenesis of HIV. The activation of NF-kB by TNF-α can enhance viral replication. Moreover, the pro-inflammatory effect of TNF-α can contribute to generalized immune activation that is pathogenic in HIV (29). Therefore, the subjects with higher baseline TNFR2 might have had greater immune activation and higher bone turnover.

Low vitamin D has been associated with low BMD and replacement of vitamin D has been shown to improve BMD (30). Our results showed that baseline 25(OH) vitamin D <32 ng/mL was associated with larger increases in total hip BMD over 48 weeks, which were independent of ALN treatment, although this association was not present when we excluded subjects with HIV RNA >400 copies/ml or baseline CD4 count <200 cells/mm3. One possible explanation is that our initial results were driven by those few patients with uncontrolled HIV replication or more severe immune-deficiency. Nevertheless, our finding support the importance of vitamin D supplementation, especially in patients with very low levels of vitamin D and uncontrolled or more advanced HIV disease, for prevention and treatment of low bone density.

The strength of this study is that it was double-blinded with longitudinal follow-up for 48 weeks. The present study had several limitations. First, the sample size might have limited our ability to detect changes in OPG/RANKL and inflammatory markers with alendronate given the large SDs we observed. SDs for OPG/RANKL and inflammatory markers were much higher than those assumed for our sample size calculation (SD=3%), which was estimated based on prior study (9). Therefore, it is possible that some of these associations might have been significant if we had a larger samples size. Second, differences in the immune activation status of the HIV-infected subjects may also reflect variability in the circulating RANKL-OPG levels and that tissue levels may be a better markers. HIV-infected subjects with detectable viral load may have significant residual inflammation and low-grade viremia, which may confound the results. Therefore, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis restricting the study population with baseline HIV RNA <400 copies/ml with and without CD4 >200 cells/mm3. Lastly, differences in antiretroviral regimen may also have differential effects on bone turnover and inflammatory markers. Percent of NNRTI use was 47% in ALN vs. 17% in placebo groups, although overall ART use differences was not significant and numbers were small. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and elucidate the mechanism. Based on our findings, HIV-infected patients with low BMD and higher levels of bone resorption or inflammation may particularly benefit from anti-resorptive treatment.

In conclusion, higher baseline bone resorption and TNF-α activity were associated with an increased response to alendronate at the lumbar spine and total hip, respectively, in HIV-infected patients. The association between low vitamin D levels and BMD response, independent of alendronate, reinforces the importance of concomitant vitamin D and calcium supplementation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; UO1 AI38558 and UO1 AI068636 and AI069501) and the Statistical and Data Management Center of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group funded by the NIAID (U01 AI38855 and U01 AI068634). The project described was supported by Award Number U01AI068636 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. This study was also funded by research grants from Merck. J.N. has received grant support from NIH Training Grant T32 (5T32EB006351-07). GAM has served as a scientific advisor and speaker for Merck. TTB has served as a consultant to Gilead, Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Abbvie, EMD-Serono, and Theratechnologies.

This study was previously presented to Endocrine Society Annual Meeting 2011, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.Brown TT, Qaqish RB. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS. 2006 Nov 14;20(17):2165–2174. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801022eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Triant VA, Brown TT, Lee H, Grinspoon SK. Fracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected versus non-HIV-infected patients in a large U.S. healthcare system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Sep;93(9):3499–3504. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaiamnuay S, Saag KG. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. What have we learned since the introduction of bisphosphonates? Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006 Jun;7(1–2):101–112. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9008-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mondy K, Powderly WG, Claxton SA, Yarasheski KH, Royal M, Stoneman JS, et al. Alendronate, vitamin D, and calcium for the treatment of osteopenia/osteoporosis associated with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Apr 1;38(4):426–431. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000145352.04440.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolland MJ, Grey AB, Horne AM, Briggs SE, Thomas MG, Ellis-Pegler RB, et al. Annual zoledronate increases bone density in highly active antiretroviral therapy-treated human immunodeficiency virus-infected men: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Apr;92(4):1283–1288. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McComsey GA, Kendall MA, Tebas P, Swindells S, Hogg E, Alston-Smith B, et al. Alendronate with calcium and vitamin D supplementation is safe and effective for the treatment of decreased bone mineral density in HIV. AIDS. 2007 Nov 30;21(18):2473–2482. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ef961d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fakruddin JM, Laurence J. HIV-1 Vpr enhances production of receptor of activated NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) via potentiation of glucocorticoid receptor activity. Arch Virol. 2005 Jan;150(1):67–78. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown TT, Ross AC, Storer N, Labbato D, McComsey GA. Bone turnover, osteoprotegerin/RANKL and inflammation with antiretroviral initiation: tenofovir versus non-tenofovir regimens. Antivir Ther. 2011;16(7):1063–1072. doi: 10.3851/IMP1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobnig H, Hofbauer LC, Viereck V, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Fahrleitner-Pammer A. Changes in the RANK ligand/osteoprotegerin system are correlated to changes in bone mineral density in bisphosphonate-treated osteoporotic patients. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(5):693–703. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perifanis V, Vyzantiadis T, Tziomalos K, Vakalopoulou S, Garipidou V, Athanassiou-Metaxa M, et al. Effect of zoledronic acid on markers of bone turnover and mineral density in osteoporotic patients with beta-thalassaemia. Ann Hematol. 2007 Jan;86(1):23–30. doi: 10.1007/s00277-006-0180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwan Tat S, Padrines M, Theoleyre S, Heymann D, Fortun Y. IL-6, RANKL, TNF-alpha/IL-1: interrelations in bone resorption pathophysiology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004 Feb;15(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siggelkow H, Eidner T, Lehmann G, Viereck V, Raddatz D, Munzel U, et al. Cytokines, osteoprotegerin, and RANKL in vitro and histomorphometric indices of bone turnover in patients with different bone diseases. J Bone Miner Res. 2003 Mar;18(3):529–538. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aukrust P, Haug CJ, Ueland T, Lien E, Muller F, Espevik T, et al. Decreased bone formative and enhanced resorptive markers in human immunodeficiency virus infection: indication of normalization of the bone-remodeling process during highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999 Jan;84(1):145–150. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gur A, Denli A, Cevik R, Nas K, Karakoc M, Sarac AJ. The effects of alendronate and calcitonin on cytokines in postmenopausal osteoporosis: a 6-month randomized and controlled study. Yonsei Med J. 2003 Feb;44(1):99–109. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2003.44.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer DC, Black DM, Garnero P, Hochberg M, Ott S, Orloff J, et al. Change in bone turnover and hip, non-spine, and vertebral fracture in alendronate-treated women: the fracture intervention trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2004 Aug;19(8):1250–1258. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eastell R, Hannon RA, Garnero P, Campbell MJ, Delmas PD. Relationship of early changes in bone resorption to the reduction in fracture risk with risedronate: review of statistical analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2007 Nov;22(11):1656–1660. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.07090b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ralston SH, Binkley N, Boonen S, Kiel DP, Reginster JY, Roux C, et al. Randomized trial of alendronate plus vitamin D3 versus standard care in osteoporotic postmenopausal women with vitamin D insufficiency. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011 Jun;88(6):485–494. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cauley JA, Danielson ME, Boudreau RM, Forrest KY, Zmuda JM, Pahor M, et al. Inflammatory markers and incident fracture risk in older men and women: the Health Aging and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007 Jul;22(7):1088–1095. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding C, Parameswaran V, Udayan R, Burgess J, Jones G. Circulating levels of inflammatory markers predict change in bone mineral density and resorption in older adults: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 May;93(5):1952–1958. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papadaki HA, Tsatsanis C, Christoforidou A, Malliaraki N, Psyllaki M, Pontikoglou C, et al. Alendronate reduces serum TNFalpha and IL-1beta, increases neutrophil counts, and improves bone mineral density and bone metabolism indices in patients with chronic idiopathic neutropenia (CIN)-associated osteopenia/osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22(6):577–587. doi: 10.1007/s00774-004-0526-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelesidis T, Kendall MA, Yang OO, Hodis H, Currier JS. Perturbations of circulating levels of RANKL-osteoprotegerin axis in relation to lipids and progression of atherosclerosis in HIV-infected and -uninfected adults: ACTG NWCS 332/A5078 Study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013 Jun;29(6):938–948. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonnelli S, Cepollaro C, Pondrelli C, Martini S, Montagnani A, Monaco R, et al. Bone turnover and the response to alendronate treatment in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999 Nov;65(5):359–364. doi: 10.1007/s002239900713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravn P, Thompson DE, Ross PD, Christiansen C. Biochemical markers for prediction of 4-year response in bone mass during bisphosphonate treatment for prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone. 2003 Jul;33(1):150–158. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer DC, Sklarin PM, Stone KL, Black DM, Nevitt MC, Ensrud KE, et al. Biochemical markers of bone turnover and prediction of hip bone loss in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 1999 Aug;14(8):1404–1410. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.8.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schousboe JT, Bauer DC, Nyman JA, Kane RL, Melton LJ, Ensrud KE. Potential for bone turnover markers to cost-effectively identify and select post-menopausal osteopenic women at high risk of fracture for bisphosphonate therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2007 Feb;18(2):201–210. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stellbrink HJ, Orkin C, Arribas JR, Compston J, Gerstoft J, Van Wijngaerden E, et al. Comparison of changes in bone density and turnover with abacavir-lamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine in HIV-infected adults: 48-week results from the ASSERT study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Oct 15;51(8):963–972. doi: 10.1086/656417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolan SE, Kanter JR, Grinspoon S. Longitudinal analysis of bone density in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Aug;91(8):2938–2945. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin MT, McMahon DJ, Ferris DC, Zhang CA, Shu A, Staron R, et al. Low bone mass and high bone turnover in postmenopausal human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Feb;95(2):620–629. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C, Watts TH. Maintaining the balance: costimulatory TNFRs and control of HIV. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2012 Aug-Oct;23(4–5):245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ooms ME, Roos JC, Bezemer PD, van der Vijgh WJ, Bouter LM, Lips P. Prevention of bone loss by vitamin D supplementation in elderly women: a randomized double-blind trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995 Apr;80(4):1052–1058. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.4.7714065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]