Abstract

The objectives of this report are to determine the association between performance-based measures of physical function with caregiver reports of physical function in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and to examine whether those associations vary by the level of patients’ cognitive functioning.

Subjects included 180 patient-caregiver dyads who are enrolled in a clinical trial testing the impact of an occupational therapy intervention plus guideline-level care to delay functional decline among older adults with Alzheimer’s disease. The primary caregiver-reported measure is the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group Activities of Daily Living Inventory (ADCS-ADL). Performance-based measures include the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) and the Short Portable Sarcopenia Measure (SPSM).

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models were used to determine the associations of each physical performance measure with ADCS-ADL, adjusting for cognition function and other covariates.

We found significant correlations between caregiver-reports and observed performance-based measures across all levels of cognitive function, with patients in the lowest cognitive group showing the highest correlation. These findings support the use of proxy reports to assess physical function among older adults with AD.

Keywords: Alzheimers disease, dementia, physical function, self-reports

Introduction

The number of worldwide cases of Alzheimer disease (AD) and related dementias is growing as the population ages; an estimated 22% of the world’s population will have dementia by the year 2050.1 There is currently no cure for AD and over a period of 5–10 years, the condition typically results in severe functional and cognitive disability. Previous studies specifically targeting physical decline have provided evidence that physical function can be improved among older adults with dementia.2,3 In a prior clinical trial, we previously reported that a collaborative care program for older adults with AD could improve behavioral symptoms, but this program did not slow the progression of physical decline.4

Previous studies have compared self-report as compared to performance-based measures of physical function in older adults, but not in the context of persons with AD and their caregivers.5–8 We are currently conducting the Alzheimer’s Disease Multiple Intervention Trial (ADMIT) which seeks to delay functional decline in AD patients.9 This study is unique in that the outcomes include two different performance-based measures of physical function, the Short Performance Physical Battery (SPPB) and Short Portable Sarcopenia Measure (SPSM) as well as a caregiver reported measure of function. The objective of this report is to determine the association of these performance-based measures with caregiver assessments of patients’ physical function and to examine whether those associations vary by the level of the patients’ cognitive functioning in a cohort of older adults with AD.

Methods

Data for this report were collected from baseline assessments of all subjects in the ADMIT trial.9 A complete description of the ADMIT protocol has been previously published.9 Briefly, ADMIT is a randomized single blind controlled clinical trial with a parallel design and a 1:1 allocation ratio comparing the effectiveness of a two-year home-based occupational therapy intervention to enhanced usual care in preventing physical decline among older adults with AD.9 Subjects were enrolled from the Healthy Aging Brain Center and its related clinical programs at Eskenazi Health in Indianapolis, Indiana.10–14 Patients were eligible if they met diagnostic criteria for possible or probable Alzheimer’s disease as determined by the physicians in this memory care practice. All patients in this practice complete formal neuropsychological testing and clinical assessments adapted from the CERAD battery of tests.9 Other inclusion criteria included community-dwelling, English-speaking patients who were aged 45 years and older who had an eligible caregiver willing to participate in the study. The caregiver was eligible if he or she was 18 years old, English speaking, and had regular access to a telephone. Following informed consent of both patients and their caregivers, a team of professional research assistants completed an in-home baseline assessment (described below). Following the baseline in-home assessment, dyads were randomized to the control or intervention group. Prior to enrollment, study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of Indiana University/ Purdue University Indianapolis.

Instruments

The primary caregiver-reported measure is the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group Activities of Daily Living Inventory (ADCS-ADL).15 This is a 23-item inventory developed by the ADCS Group that is administered to the patient’s caregiver by trained research staff. The caregiver is asked to focus on the patient’s performance over the past month. Notably, the caregiver reports on what the patient actually did rather than an assessment of what the patient might be able to do. The inventory assesses the traditional activities of daily living (e.g., bathing) as well as variations on instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., using the telephone). 15 Scores vary from 0 to 78 with higher scores indicating greater levels of function.

Patient’s cognitive function was measured by the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE), a 30 point scale, with lower scores indicating increased cognitive impairment.16 We use the MMSE is this study for three reasons. First, scores on the MMSE allow other researchers to compare our study sample with previously reported study samples with dementia on this commonly used measure of cognitive function. Second, we sought to examine whether subjects with poorer cognitive function as measured by the MMSE would be able to understand the examiner instructions to properly complete performance-based measures. Third, we use the MMSE score to determine if the correlations between proxy-reported and performance-based measures deteriorate as cognitive function worsens.

Physical performance measures include the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) and the Short Portable Sarcopenia Measure (SPSM). The SPPB is a standardized measure of lower extremity physical performance that includes walking, balance, and power tasks. It has been used in a broad range of epidemiological studies of aging.17–20 This scale has proven reliable and valid for predicting disability, nursing home placement, hospital admission, and mortality.8,20–23 The SPPB score is based on timed measures of standing balance, walking speed, and repeated chair rises, each of which is scored 0 to 4 based on standardized criteria. Total scores vary from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating better function. The SPSM was conceptualized as a measure of sarcopenia that combines muscle quantity and function.24 The SPSM can be used to follow change in muscle status over time with each person as his or her own control. The scale is based on timed chair rises, body mass index, and grip strength. Scores vary from 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating less sarcopenia. Patients only received total scores on the SPPB and SPSM if they received a score for each item within the scale. Performance tasks that were refused were not scorable. Patients who were unable or unsafe to stand on a scale did not receive a score for SPSM.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, and range for continuous variables and frequency and percent in each category for categorical variables were calculated. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) models and chi-square tests were used to compare baseline characteristics across the MMSE quartiles. Pearson correlation coefficients and their p-values were calculated for the associations of the two performance-based measured with the ADCS-ADL. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to identify baseline characteristics significantly associated with the ADCS-ADL. These baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 but only significant variables are shown in Table 2. The two physical performance measures were each regressed against ADCS-ADL in analyses adjusting for these same covariates. Stepwise and backwards selection methods were used to identify final separate parsimonious models for the ADCS-ADL scores including covariates significant at the alpha=0.05 level. Standardized regression coefficients were shown from the models where one standard deviation increase on the independent variable indicates the change in standard deviations of the dependent variable. Interactions between the covariates with SPSM or SPPB were investigated and included if significant at the alpha=0.05 level. If the final model included significant interactions, partial correlation coefficients were also calculated after stratifying by that covariate.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients and their Caregivers (n=180)

| MMSE Quartiles | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Overall | 1st (0–15) (n=41) |

2nd (16–20) (n=38) |

3rd (21–24) (n=42) |

4th (25–29) (n=47) |

p-value | |

| Patient | |||||||

| Female gender, n (%) | 168 | 116 (69.0) | 27 (65.9) | 24 (63.2) | 33 (78.6) | 32 (68.1) | 0.4548 |

| White race, n (%) | 168 | 70 (41.7) | 17 (41.5) | 14 (36.8) | 18 (42.9) | 21 (44.7) | 0.9044 |

| Age, mean ± SD | 168 | 78.5 ± 8.7 | 77.7 ± 9.1 | 80.3 ± 8.0 | 78.0 ± 7.5 | 78.1 ± 9.9 | 0.5391 |

| What is the highest grade or year of school you completed, n (%) | 166 | 0.2823 | |||||

| Grades 1 through 8 (Elementary) | 34 (20.5) | 8 (20.0) | 6 (16.2) | 11 (26.2) | 9 (19.1) | ||

| Grades 9 through 11 (Some high school) | 43 (25.9) | 6 (15.0) | 10 (27.0) | 12 (28.6) | 15 (31.9) | ||

| Grade 12 or GED (High school graduate) | 49 (29.5) | 15 (37.5) | 15 (40.5) | 12 (28.6) | 7 (14.9) | ||

| College 1 year to 3 years (Some college or technical school) | 19 (11.4) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (10.8) | 3 (7.1) | 7 (14.9) | ||

| College 4 years or more (College graduate) | 21 (12.7) | 6 (15.0) | 2 (5.4) | 4 (9.5) | 9 (19.1) | ||

| ADCS-ADL, mean ± SD | 168 | 48.9 ± 16.7 | 33.8 ± 15.3 | 49.2 ± 14.6 | 51.7 ± 13.1 | 59.3 ± 12.7 | <0.0001 |

| MMSE, mean ± SD | 168 | 19.3 ± 7.2 | 8.7 ± 5.2 | 18.7 ± 1.4 | 22.5 ± 1.1 | 26.3 ± 1.2 | <0.0001 |

| SPPB, mean ± SD | 168 | 4.2 ± 3.0 | 2.9 ± 2.2 | 4.0 ± 2.8 | 4.6 ± 3.0 | 5.2 ± 3.3 | 0.0018 |

| SPSM, mean ± SD | 136 | 3.9 ± 3.6 | 3.3 ± 3.2 | 3.0 ± 2.9 | 4.6 ± 3.4 | 4.6 ± 4.4 | 0.1437 |

| Caregiver (n=164)* | |||||||

| Caregiver is Spouse of Subject, n (%) | 164 | 46 (28.0) | 12 (30.8) | 8 (21.1) | 12 (30.0) | 14 (29.8) | 0.7505 |

| Age, mean ± SD | 160 | 57.4 ± 12.2 | 55.9 ± 13.1 | 57.5 ± 12.5 | 57.6 ± 12.0 | 58.3 ± 11.6 | 0.8365 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 164 | 118 (72.0) | 28 (71.8) | 26 (68.4) | 29 (72.5) | 35 (74.5) | 0.9426 |

| White race, n (%) | 164 | 68 (41.5) | 15 (38.5) | 15 (39.5) | 17 (42.5) | 21 (44.7) | 0.935 |

4 caregivers cared for 2 subjects each

Table 2.

Results of analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models on ADCS-ADL scores by SPPB or SPSM after adjusting for MMSE Quartiles, Caregiver Relationship to Patient, and Significant Interactions

| ADCS-ADL | ||

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficient |

P-value | |

| SPPB | 0.28 | 0.0043 |

| MMSE quartiles | <0.0001 | |

| 1st | −0.78 | <0.0001 |

| 2nd | −0.30 | 0.0128 |

| 3rd | −0.17 | 0.1626 |

| 4th | Ref | Ref |

| Caregiver is Spouse | −0.15 | 0.0089 |

| Interaction between SPPB and MMSE quartiles | 0.0241 | |

| 1st | 0.29 | 0.0043 |

| 2nd | 0.11 | 0.3374 |

| 3rd | 0.0005 | 0.9969 |

| 4th | Ref | Ref |

| SPSM | 0.29 | 0.389 |

| MMSE quartiles | <0.0001 | |

| 1st | −0.55 | <0.0001 |

| 2nd | −0.26 | 0.0027 |

| 3rd | −0.15 | 0.0716 |

| 4th | Ref | Ref |

| Caregiver is Spouse | −0.15 | 0.0468 |

| Age≥80 | 0.19 | 0.0811 |

| Interaction between SPSM and Age≥80 | −0.28 | 0.0108 |

Results

One-hundred eighty patient-caregiver dyads were enrolled in the study between March 2011 and October 2013; 91 (50.6%) were randomized to receive the occupational therapy intervention. Of the total enrolled patients, 175 had ADCS-ADL scores, 174 patients had SPPB scores, 144 had SPSM scores, and 179 had MMSE scores. The final study sample was composed of the 168 patients with completed ADCS-ADL, SPPB and MMSE scores.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients and caregivers both overall and stratified by quartiles based upon MMSE scores. Among all patients, 69% were women and 42% were white. The mean (SD) age was 78 (9) years with a range from 53–102 and a median of 79. Only 24% had attained education beyond high school. Mean ADCS-ADL and MMSE scores are consistent with other clinical trials reported in the literature among older adults with AD.25,26 There were 164 caregivers for the 168 patients; 160 caregivers cared for one patient and 4 cared for 2 patients each. There were no differences in patient or caregiver demographic characteristics or SPSM scores across the MMSE quartiles (p>0.05 for all). However, ADCS-ADL and SPPB scores differed significantly according to MMSE levels. In particular, those in the highest MMSE quartile had significantly better ADCS-ADL scores than those in all other quartiles (p<0.05) and higher SPPB scores than those in the lowest two quartiles (p<0.05).

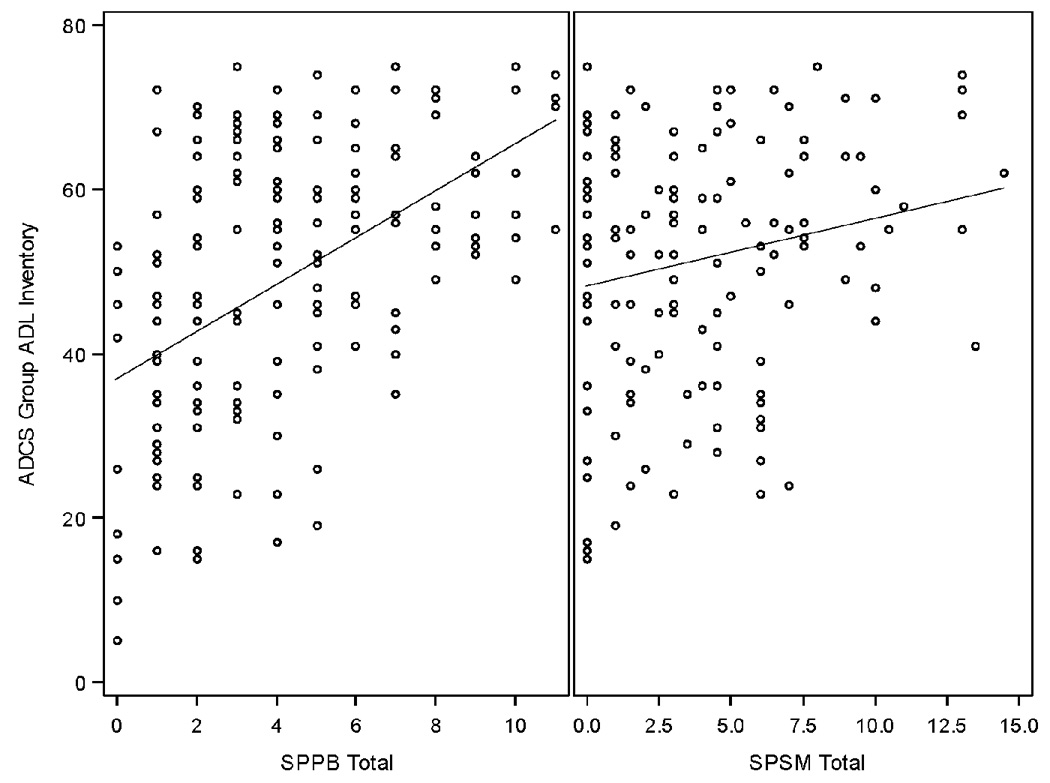

Figure 1 shows scatter plots and regression lines between each of the performance-based physical function measures with the ADCS-ADL total. SPPB was highly correlated with the ADCS-ADL (r=0.52, p<0.0001). SPSM was modestly but significantly correlated with the ADCS-ADL (r=0.20, p=0.0202).

Figure 1.

Scatter plots and univariate linear regression lines of the association of the performance-based physical function measures with the ADCS-ADL score

The standardized Cronbach coefficient alpha was 0.77 for the SPPB and 0.42 for the SPSM. Results on the SPPB were comparable to established internal consistency of 0.76.8. There are no published results on the internal consistency of SPSM. However, given that there are only three items in the SPSM, it is possible that Cronbach alpha underestimates its internal consistency. We were encouraged that we did not find floor or ceiling effects with the SPPB in this patient population although there may be a slight floor effect for the SPSM. The range for the SPSM is 0–14.5 with a mean of 3.9 and a standard deviation of 3.6. The range for the SPPB was 0–11 with a mean of 4.2 and a standard deviation of 3.0. There were 28 patients (20.6%) who scored a 0 on the SPSM and 10 (6.0%) who scored 0 on the SPPB. The correlation between the SPSM and SPPB was 0.35 (p<0.0001; n=136).

Table 2 shows the results from the ANCOVA models on the association between the reported measure (ADCS-ADL) and performance-based measures (SPPB and SPSM) including significant interactions. We found a significant interaction between SPPB and the MMSE quartiles (p=0.0241) in the model on ADCS-ADL, indicating significant differences in the correlations between SPPB and ADCS-ADL across MMSE quartiles. In fact, the partial correlation coefficient was significantly higher for patients in the lowest MMSE quartile group (ρ=0.65, p=0.0043) when compared to patients in the highest MMSE quartile group (ρ=0.43). While spousal caregiver relationship was associated with lower ADCS-ADL scores, this relationship had no impact on the correlation between SPPB and ADCS-ADL.

Looking at the models using SPSM, a significant interaction between age group (dichotomized at the median) and SPSM was found in the model for ADCS-ADL (p=0.0108). Patients younger than 80 had a significantly higher partial correlation coefficient (ρ=0.33) between the SPSM score and ADCS-ADL than older subjects (ρ= −0.09). Similar to SPPB, spousal caregiver relationship had no impact on correlations between SPSM and ADCS-ADL.

Discussion

Obtaining reliable physical function assessments from cognitively impaired study subjects poses challenges in terms of subject’s ability to provide self-reports and the subject’s understanding and ability to perform physical tasks correctly.27 While there is no gold standard measure of physical function among older adults with AD, in the study section review of our ongoing clinical trial9 reviewers recommended that performance-based measures be collected rather than relying on proxy reports of physical function. Previous studies have used SPPB23,28–30 and SPSM24 as performance based measures in older adults, but not necessarily focused on older adults with dementia. The ADCS-ADL is a standardized measure and has been widely used in prior AD clinical trials but it relies on self-reports of caregivers rather than performance-based assessments.9,31–33 This study examines whether proxy reports are correlated with performance-based measures. We found significant correlations between caregiver-reports using the ADCS-ADL when compared to observed performance-based measures across all levels of cognitive function, with patients in the lowest cognitive group showing the highest correlation. These results also indicate that the SPPB and SPSM appear not to be significantly affected by impaired cognition and thus are reasonable performance-based physical function measures to include in trials targeting older adults with dementia. We also found that proxy reports are correlated with performance-based measures and thus could offer a lower cost, more practical measure of physical function in the context of clinical trials for AD.

A pilot study by Fox et al. examined the psychometric properties of certain functional and anthropometry measures including SPPB and grip strength among dementia patients living in residential aged care. While they found grip strength and anthropometric measures to be reliable in this population, other functional measures like the SPPB were found to have low levels of absolute reliability and high variance at the individual level. Data on MMSE scores or level of dementia was not reported in that study.27 Bruce-Keller et al. demonstrated the complex interaction between cognitive function and physical performance, finding changes in individual cognitive domains to be more correlated than global cognitive measures, specifically in early changes to gait and SPPB in mildly demented patients.34 Building on these findings, this study incorporated correlations across the cognitive spectrum, taking into account MMSE of patients as well as caregiver-reported function and professionally-observed patient performance. Notably, the SPPB had stronger correlations with ADCS-ADL than SPSM. This finding may suggest that mobility and standing balance are more closely associated with function than lean mass and strength in patients such as those enrolled in this study.

Performance-based measures might be argued as ideal for assessing function in persons with AD, but these measures have important practical limitations. The SPPB is a well-established measure of lower body physical functioning that was shown to identify persons at greater risk for functional decline.24 The SPPB, in conjunction with the SPSM which combines muscle quantity and function 24, could be considered a well-balanced performance-based physical assessment. However, these scales were not specifically designed for assessment of persons with AD. Each assessment was completed in the patient’s home. This factor creates differences in assessment administration because each home environment is unique. Standardization is a challenge for items like chair rises, which require the patient to have a hard-surfaced, average height chair, and open wall space to use. Gait speed was occasionally administered with limited space, and moving furniture was sometimes necessary. It was sometimes difficult to create a comfortable and safe environment for movement and positioning during balancing. Environmental distractions during the testing such as interruptions by family members, televisions, or other media were additional obstacles for research staff

Administration of the ADCS-ADL posed its own set of practical limitations in data collection in the ADMIT trial. Caregivers varied in their understanding of the ADCS-ADL questions and additional explanation was often needed. The multiple choice answer selections from the ADCS-ADL required clarification, and sometimes none of the options fit the caregivers’ explanation. In these circumstances the caregiver would be prompted to choose the “best option.” Furthermore, ADCS-ADL questions tended to be catalysts for conversation and stories that caregivers wanted to share. Research assistants at times found it difficult to keep the interview on track while respecting additional information caregivers were willing to share.

The ADMIT data collection was able to incorporate a home-based evaluation-setting for both the patient assessments and caregiver reports. An important consideration when choosing this method over clinic or phone interviews is additional time and travel expenses. In-home assessments were typically completed in 40–70 minutes. Each home visit required an average of 14 miles of driving distance which equated to $8 in mileage reimbursement. An hour was typically allotted for each in-home assessment with 30–60 minutes of travel time in between those visits.

Overall, our findings indicate that (a) caregiver-reports provide a reliable portrayal of how patients will perform on performance-based measures of physical function and cognition and (b) in this trial cohort, our two performance-based measures (SPPB and SPSM) appeared to be valid and not affected by the patient’s degree of cognitive impairment. In fact, the strongest correlation was shown in the lowest cognitive group. Going forward, these three outcome metrics (SPPB, SPSM, and ADCS-ADL) show to be acceptable measures for use in AD patients and the ADMIT trial.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIA grant R01 AG034946

References

- 1.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2013 Jan;9(1):63–75.e62. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graff MJ, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Thijssen M, Dekker J, Hoefnagels WH, Rikkert MG. Community based occupational therapy for patients with dementia and their care givers: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2006 Dec 9;333(7580):1196. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39001.688843.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLaren AN, Lamantia MA, Callahan CM. Systematic review of non-pharmacologic interventions to delay functional decline in community-dwelling patients with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2013 Aug;17(6):655–666. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.781121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austrom M, Hartwell C, Moore PS, et al. An integrated model of comprehensive care for people with Alzheimer's disease and their caregivers in a primary care setting. Dementia. 2006;5:339–3352. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shumway-Cook A, Patla A, Stewart AL, Ferrucci L, Ciol MA, Guralnik JM. Assessing Environmentally Determined Mobility Disability: Self-Report Versus Observed Community Mobility. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(4):700–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latham NK, Mehta V, Nguyen AM, et al. Performance-based or self-report measures of physical function: which should be used in clinical trials of hip fracture patients? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008 Nov;89(11):2146–2155. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoeymans N, Feskens EJ, van den Bos GA, Kromhout D. Measuring functional status: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between performance and self-report (Zutphen Elderly Study 1990–1993) Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1996 Oct;49(10):1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994 Mar;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Schmid AA, et al. Alzheimer's disease multiple intervention trial (ADMIT): study protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. Trials. 2012;13:92. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callahan CM, Weiner M, Counsell SR. Defining the Domain of Geriatric Medicine in an Urban Public Health System Affiliated with an Academic Medical Center. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1802–1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boustani MA, Sachs GA, Alder CA, et al. Implementing innovative models of dementia care: The Healthy Aging Brain Center. Aging & Mental Health. 2011;15(1):13–22. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.496445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.French DD, Lamantia MA, Livin LR, Herceg D, Alder CA, Boustani MA. Healthy aging brain center improved care coordination and produced net savings. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2014 Apr;33(4):613–618. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Weiner M, et al. Implementing dementia care models in primary care settings: The Aging Brain Care Medical Home. Aging Ment Health. 2011 Jan;15(1):5–12. doi: 10.1080/13607861003801052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callahan CM, Sachs GA, Lamantia MA, Unroe KT, Arling G, Boustani MA. Redesigning systems of care for older adults with Alzheimer's disease. Health affairs. 2014 Apr;33(4):626–632. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, et al. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;(11 Suppl 2):S33–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, et al. The ankle brachial index independently predicts walking velocity and walking endurance in peripheral arterial disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998 Nov;46(11):1355–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDermott MM, Green D, Greenland P, et al. Relation of levels of hemostatic factors and inflammatory markers to the ankle brachial index. Am J Cardiol. 2003 Jul 15;92(2):194–199. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00537-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDermott MM, Liu K, Greenland P, et al. Functional decline in peripheral arterial disease: associations with the ankle brachial index and leg symptoms. Jama. 2004 Jul 28;292(4):453–461. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penninx BW, Ferrucci L, Leveille SG, Rantanen T, Pahor M, Guralnik JM. Lower extremity performance in nondisabled older persons as a predictor of subsequent hospitalization. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2000 Nov;55(11):M691–M697. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.11.m691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995 Mar 2;332(9):556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2000 Apr;55(4):M221–M231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller DK, Wolinsky FD, Andresen EM, Malmstrom TK, Miller JP. Adverse outcomes and correlates of change in the Short Physical Performance Battery over 36 months in the African American health project. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2008 May;63(5):487–494. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.5.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller DK, Malmstrom TK, Andresen EM, et al. Development and validation of a short portable sarcopenia measure in the African American health project. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2009 Mar;64(3):388–394. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006 May 10;295(18):2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Annals of internal medicine. 2008 Mar 4;148(5):379–397. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox B, Henwood T, Neville C, Keogh J. Relative and absolute reliability of functional performance measures for adults with dementia living in residential aged care. International psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2014 Jul 3;:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214001124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Legrand D, Vaes B, Mathei C, Adriaensen W, Van Pottelbergh G, Degryse JM. Muscle strength and physical performance as predictors of mortality, hospitalization, and disability in the oldest old. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014 Jun;62(6):1030–1038. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mijnarends DM, Meijers JM, Halfens RJ, et al. Validity and reliability of tools to measure muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013 Mar;14(3):170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eggermont LH, Leveille SG, Shi L, et al. Pain characteristics associated with the onset of disability in older adults: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the Elderly Boston Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014 Jun;62(6):1007–1016. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu-Seifert H, Siemers E, Sundell K, et al. Cognitive and Functional Decline and Their Relationship in Patients with Mild Alzheimer's Dementia. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2014 Aug 13; doi: 10.3233/JAD-140792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castilla-Rilo J, Lopez-Arrieta J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Ruiz M, Sanchez-Sanchez F, Trincado R. Instrumental activities of daily living in the screening of dementia in population studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2007 Sep;22(9):829–836. doi: 10.1002/gps.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blankevoort CG, van Heuvelen MJ, Boersma F, Luning H, de Jong J, Scherder EJ. Review of effects of physical activity on strength, balance, mobility and ADL performance in elderly subjects with dementia. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders. 2010;30(5):392–402. doi: 10.1159/000321357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruce-Keller AJ, Brouillette RM, Tudor-Locke C, et al. Relationship between cognitive domains, physical performance, and gait in elderly and demented subjects. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2012;30(4):899–908. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]