Abstract

This short-term longitudinal study examined whether the association between bullying perpetration and later physical dating violence perpetration and mediators of that association (via anger, depression, anxiety, and social status), varied depending on level of bullying victimization. Differences have been noted between those who bully but are not victims of bullying, and those who are both bullies and victims. These differences may influence dating violence risk and the explanations for why bullying leads to dating violence. Data were from dating adolescents in three rural counties who completed self-administered questionnaires in the fall semester of grades 8–10 and again in the spring semester. The sample (N =2,414) was 44.08% male and 61.31% white. Bullying perpetration in the fall semester predicted physical dating violence perpetration in the spring semester when there was no bullying victimization, but not when there was any bullying victimization. Bullying perpetration was positively associated with anger at all levels of bullying victimization and with social status when there was no or low amounts of victimization; it was negatively associated with social status at high levels of victimization. Bullying victimization was positively associated with anger, depression, and anxiety at all levels of bullying perpetration. Anger mediated the association between bullying perpetration and dating violence, regardless of level of victimization; depression, anxiety, and social status did not mediate the association at any level of bullying victimization. The findings have implications for dating violence prevention efforts and for future research on the link between bullying and dating violence.

Keywords: bullying involvement, dating abuse, dating violence, conditional indirect effects

INTRODUCTION

Evidence suggests that adolescents who bully their peers also may abuse their dating partners. In cross-sectional studies, bullying is positively correlated with adolescent dating violence perpetration (Connolly, Pepler, Craig, & Taradash, 2000; Miller et al., 2013; Pepler et al., 2006) and adult intimate partner violence perpetration (Falb et al., 2011). In longitudinal studies, bullying predicted physical dating violence perpetration by both boys and girls in middle school (Foshee et al., 2014) and later sexual harassment (Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012; Pellegrini, 2001). Adolescents who bully their peers can also be victims of bullying, and whether bullying perpetrators at greatest risk for dating violence perpetration are those who have or have not also been victims of bullying has not previously been examined. However, numerous studies (e.g., Georgiou & Stavrinides, 2008; Haynie et al., 2001; Stein, Dukes, & Warren, 2007) have found differences between those who bully but are not victims of bullying (i.e., bullies), and those who are both bullies and victims of bullying (i.e., bully victims). These differences provide different explanations for the link between bullying and dating violence perpetration. The current study used longitudinal data to determine whether the association between bullying perpetration and physical dating violence perpetration, and the explanations for the link between bullying perpetration and dating violence perpetration, varied depending on adolescents’ degree of bullying victimization.

Bully victims have been described as temperamental (Georgiou & Stavrinides, 2008), irritable, restless and hostile (Olweus, 1978), and as being highly emotional, with significant deficits in emotional control and self-regulation (De Bolle & Tackett, 2013; Haynie et al., 2001; Schwartz, 2000). They have been found to have higher levels of anxiety (Isolan, Salum, Osowski, Zottis, & Manfro, 2013; Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpelä, Rantanen & Rimpelä, 2000; Menesini, Modena, & Tani, 2009; Swearer, Song, Cary, Eagle, & Mickelson, 2001), and depression than bullies (Austin & Joseph, 1996; Menesini et al., 2009; Özdemir & Stattin, 2011), although there are exceptions (Swearer et al., 2001). They also have been found to have more anger and greater difficulty controlling their anger than bullies (Camodeca, Goossens, Schuengel, & Terwogt, 2003; Georgiou & Stavrinides, 2008). Perry, Perry and Kennedy (1992) described bully victims (or aggressive victims) as “ineffectual aggressors” that “become emotionally aroused, escalate the conflict into aggression, but, importantly, usually end up losing the battle amid exaggerated displays of frustration and distress” (p. 310). Thus, it has been suggested that bully victims’ aggression is motivated by emotional distress and reactivity (Pellegrini, 1998; Ragatz, Anderson, Fremouw, & Schwartz, 2011; Schwartz, Proctor, & Chien, 2001).

In contrast, bullies have been found to show no more emotional distress than those not involved in bullying (Menesini et al., 2009; Özer, Totan, & Atik, 2011) and they exhibit fewer behavioral and self-control problems than bully victims (Haynie et al., 2001). They have been described as “cool manipulators” (Wolke, Woods, Bloomfield, & Karstadt, 2000), such that their aggression is not emotion based, but rather planned, controlled, and goal oriented. The primary goal is to achieve gains in social status (Schwartz, 2000; Schwartz, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1997; Schwartz et al., 2001), and this appears to be effective since bullies enjoy greater peer acceptance than either victims only (victims) or bully victims (Perren & Hornung, 2005). Perry et al. (1992) described bullies as “effective aggressors” because their bullying is an “efficacious social strategy.” Thus, in contrast to bully victims who use aggression out of a failure to regulate their emotions, bullies use aggression instrumentally (Schwartz, 2000).

Thus, both types of bully perpetrators (bullies and bully victims) may be at greater risk of abusing dating partners than those who do not bully, but for different reasons. Bully victims may be at greater risk because of their emotional distress. Longitudinal studies have found that emotional distress and more specifically, anger, depression, and anxiety predict later dating violence perpetration (Foshee, Reyes, & Ennett, 2010; McCloskey & Lichter, 2003; Williams, Connolly, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2008; Wolfe, Wekerle, Scott, Straatman, & Grasley, 2004). Furthermore, lack of emotional self-regulation, which is characteristic of bully victims, predicts the use of aggression against partners (Finkel, DeWall, Slotter, Oaten, & Foshee, 2009). Thus, emotional distress may be the mechanism linking bullying perpetration to dating violence perpetration for those who are also victims of bullying.

In contrast, social status may be the mechanism linking bullying perpetration to dating violence perpetration for those who are not also victims of bullying. As noted above, bullying perpetrated by bullies is a means of gaining and maintaining social status; numerous studies have found that bullying can be effective in increasing social status among peers (Faris, 2012; Sijtsema, Veenstra, Lindenberg, & Salmivalli, 2009). High social status has been associated with dating violence perpetration by both boys and girls (Foshee et al., 2013). Several explanations have been given for this link (Foshee et al., 2014). Faris and Felmlee (2011) suggest that adolescents with high social status have greater control over information (e.g., rumors) and resources (e.g., social options on weekends) and thus are better positioned to manipulate social situations and exert control over dates. Moreover, high as compared to low status adolescents have more access to partners and thus may be less fearful of the negative consequences of violence on a dating relationship. At the same time, adolescents thrust into dating due to high status may not have developed the social skills needed for dating and this could increase their likelihood of responding poorly to conflict with dating partners (Connolly et al., 2000). As another explanation for the linkage between social status and dating violence, adolescent dating has the potential for producing embarrassing situations, such as those that arise from insensitive comments made by a date in front of others, which could threaten social status. One way of decreasing the likelihood of embarrassing situations is to exert control over dating partners. Although several researchers have suggested that high social status may explain the link between bullying perpetration and dating violence perpetration (Connolly et al., 2000; Espelage & Holt, 2001; Foshee et al., 2014), this mechanism has not been examined empirically.

THE CURRENT STUDY

In this study, we examined whether bullying perpetration by dating adolescents in the fall semester of grades 8–10 predicted physical dating violence perpetration in the spring semester of the same school year, and whether that association and mechanisms explaining the association varied depending on the degree of bullying victimization. We predicted that both bully victims and bullies would be at greater risk of perpetrating physical dating violence that those who do not bully, but that the mechanism, or mediators, responsible for the greater risk of physical dating violence would differ for bully victims and bullies. We expected bully victims to be at risk of perpetrating physical dating violence because of greater emotionality, specifically higher levels of anger, anxiety, and depression; and we expected bullies to be at greater risk of perpetrating physical dating violence because of the higher social status afforded to them.

To test these hypotheses we used the statistical interaction between the degree of bullying perpetration and degree of bullying victimization to characterize bullies and bully victims, rather than categorizing adolescents into bully involvement categories (bullies, bully victims, victims, non-involved). We did not assign adolescents to bully involvement categories because that requires identifying cut-off values for defining one as a bully and a victim and it is conceptually difficult to determine the most appropriate cut-off values. Indeed, the selection of cut-off values for defining a bully and a victim has been found to affect findings (Schwartz, 2000). Furthermore, using the categorizing approach can reduce sample size because of inability to classify some adolescents into the categories based on cut-off values (Schwartz, 2000). Archer, Ireland and Power (2007) suggested that examining the interaction between bullying perpetration and bullying victimization when predicting outcomes makes it possible to determine if there are, in fact, any qualitative differences in outcomes for bully victims beyond the additive effects of bullying and being victimized. Also, by examining the interaction between bullying perpetration and bullying victimization it is possible to test hypotheses in a “conditional indirect effects” or “moderated mediation model” framework, which matches our study expectations.

As noted by Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes (2007), conditional indirect effects or moderated mediation occurs when “the strength of an indirect effect depends on the level of some variable, or in other words, when mediation relations are contingent on the level of the moderator” (p. 193). In our case, we expected that the mediational process linking bullying perpetration in the fall semester to dating violence perpetration in the spring semester would be contingent on the degree of victimization from bullying experienced by those who perpetrated the bullying. A common approach to testing for mediation is to first examine the association between an independent variable and a mediator (typically referred to as the a path), and between the mediator and the outcome, controlling for the independent variable (typically referred to as the b path), and then assess the statistical significance of the indirect path (a*b; Hayes, 2013). Moderated mediation occurs when the association between an independent variable and a mediator variable (the a path) varies by a moderator, or the effect of a mediator variable on an outcome (b path) varies by a moderator, or both (Hayes, 2013; James & Brett, 1984).

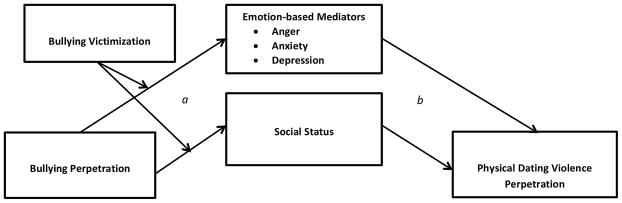

We expected that the association between bullying perpetration and the mediators examined (i.e., anger, depression, anxiety and social status: the a paths) would be conditional on the degree of bullying victimization, which would produce conditional indirect effects (see Fig. 1). More specifically, we expected bullying perpetration and bullying victimization to interact in predicting the mediators such that those who engaged in bullying perpetration and also experienced higher levels of bullying victimization (bully victim) would have higher levels of anger, anxiety, and depression than those reflecting other combinations of bullying perpetration and victimization. We expected that those who engaged in bullying perpetration but reported no bullying victimization (bullies) would have higher social status than in other combinations of bullying perpetration and victimization. As a result of these differences, we expected that the indirect effect of bullying perpetration on dating violence perpetration through emotional distress mediators (i.e., anger, anxiety, and depression) would be significant at higher degrees of bullying victimization, and we expected that the indirect effect of bullying perpetration on dating violence perpetration through social status would be significant when there was no bullying victimization.

Fig. 1.

The conceptual model guiding study hypotheses.

We tested our hypotheses using an innovative social network approach to measure bullying perpetration and victimization, described in detail later, and which has some strengths over typical approaches to measuring bully victimization and perpetration, such as self-reports (e.g., Atik & Güneri, 2013; Dukes, Stein, & Zane, 2009; Georgiou & Stavrinides, 2008) and teacher (e.g., Bowes et al., 2009; De Bolle & Tackett, 2013; Salmivalli & Nieminen, 2002) or peer (e.g., Bowers, Smith, & Binney, 1994; Schwartz, 2000; Veenstra et al., 2005) ratings of bullying behavior, each of which could underestimate reports of bullying behavior. In addition, reports of bullying perpetration and victimization were limited to those against or from peers of the same sex to decrease the likelihood that reports of bullying behavior could refer to dating partners, which would result in measurement redundancy between the bullying and dating violence measures and inflate associations.

Also, we tested our hypotheses controlling for potential confounders of the proposed associations, including demographic variables (sex, race, and grade in school of the adolescent, family structure, and parent education) and family aggression. The demographic characteristics have been associated with both bullying perpetration (Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Fredland, 2008) and dating violence (Foshee & Reyes, 2011; Vagi et al., 2013), and thus, if unaccounted for, could produce spurious relationships between bulling and dating violence. Tenets of both social learning theory (Bandura, 1973) and more specifically, the inter-generational transmission of violence (O’Leary, 1988) suggest that exposure to aggression among family members could influence adolescents to both bully their peers and use violence against dating partners. According to social learning theory, behavior is learned by observing the behavior of others, especially family members, and its functionally positive consequences, which produce positive outcome expectations for enacting the behavior (Bandura, 1973). The inter-generational transmission of violence theory (O’Leary, 1988) is an application of the principles of social learning theory to the transmission of aggression in the family of origin to offspring. Numerous empirical studies have found that children and adolescents exposed to aggression between family members are at increased risk of bullying peers (Baldry, 2003; Schwartz et al., 1997; Smokowski & Kopasz, 2005), using violence against dates (Capaldi, Dishion, Stoolmiller, & Yoerger, 2001; Foshee, Bauman, & Linder, 1999; O’Donnell et al., 2006; Reitzel-Jaffe & Wolfe, 2001; Tschann et al., 2009), and of having more emotional distress including anger, anxiety, and depression (Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003) than those not exposed to family aggression. Thus, unaccounted for, family aggression could produce spurious relationships when testing the hypothesized associations.

METHODS

Study Overview

Data were from the Context Study, a multi-wave longitudinal investigation of contextual influences on adolescent health risk behavior (Ennett et al., 2008a; Foshee et al., 2011). The study was conducted in three primarily rural North Carolina county school systems which included 8 middle schools, 2 K-8 schools, 3 alternative schools, and 6 high schools (19 schools total). Adolescents were eligible for participation if they were able to complete the survey in English and were not in special education programs or out of school due to long-term suspension. Adolescents completed self-administered questionnaires in the fall semester of the 8th (ages 13–14), 9th (ages 14–15), and 10th (15–16) grades (N =5,017; 79.10% of those eligible) and again in the spring semester (N =4,272; 85.2% of those who completed the fall assessment). Of the 4,272 adolescents who completed both assessments, 3,161 (74.0%) reported at the spring assessment that they had dated; the analysis for this study were conducted in the sample of dating adolescents. Trained data collectors administered the questionnaires in classrooms. Parents had the opportunity to refuse consent for their child’s participation by returning a written form or calling a toll-free number. Assent was obtained prior to survey administration from adolescents whose parents did not refuse their child’s participation. The Institutional Review Board for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill approved the study.

Measures

Bullying perpetration and bully victimization

At the fall assessment, data collectors provided each participant a student directory that listed alphabetically all enrolled students along with a unique four-digit peer identification number for each student. Adolescents were instructed to write the first names (or initials) and ID number of up to five schoolmates who, in the past 3 months, “picked on or were mean” to them and up to five schoolmates whom they “picked on or were mean to.” Students were instructed to disregard playful teasing and focus only on harmful actions. Social network analyses of these data were used to create bullying perpetration and bullying victimization variables. The bullying perpetration variable was based on self-reports of bullying from the respondent and also from the reports of their peers on whether the respondent had bullied them (range =0–7 peers bullied); thus a bullying tie from A to B was considered present if either A nominated B as a victim or B nominated A as a bully. The bullying victimization variable was the number of same sex peers who had bullied the respondent based on self-reports of victimization from the respondent and on the reports of peers on whether they had bullied the respondent (range =victimized by 0–15 peers); thus a victimization tie from A to B was considered present if either A nominated B as bullying them or B nominated A as someone they bullied. This social network approach decreases the likelihood of under-reporting of bullying involvement because if a bully (or victim) did not admit to bullying someone (or being victimized), they would still be identified as a bullying perpetrator (or victim) if another student in the school identified them as someone who bullied them (or that they had bullied).

Emotion-based mediators

Anger, anxiety, and depression were measured at the fall assessment. Anger was measured with three items from the multiple affect adjective checklist (Zuckerman & Lubin, 1985). Adolescents were asked “In the past 3 months, how often did you feel each of the following (mad, angry, furious) ?” Response options ranged from 0 for never to 4 for always; items were summed and averaged (mean =1.58; STD =0.93; range =0–4; α=.63). Anxiety was measured with seven items, for example, “I worried about what was going to happen,” from the revised childrens manifest anxiety scale (Reynolds & Richmond, 1979), again in reference to the prior 3 months, with response options ranging from 0 for strongly disagree to 4 for strongly agree; these items were also summed and averaged (mean =1.81; STD =1.12; range =0–4; α=.89). Depression was measured with three items from a depression scale developed by Angold, Costello, Messer, & Pickles (1995), for example “I hated myself,” again in reference to the past 3 months and with response options ranging from 0 for strongly disagree to 4 for strongly agree; items were summed and averaged (mean =1.17; STD=1.30; range =0–4; α=.92).

Social status mediator

The social status variable, betweenness centrality, was created using social network analysis of data from the fall assessment. Centrality is a social network indicator of social status that assesses prominence and prestige in the network based on pattern of friendship ties (Alexander, Piazza, Mekos, & Valente 2001; Ennett et al., 2006, 2008b; Espelage, Wasserman, & Fleisher, 2007; Faris & Felmlee, 2011). Although multiple measures of centrality are available, in all measures, central adolescents are those who are extensively or strategically connected with other adolescents in the network. We used betweenness centrality, which is a measure of the extent to which an adolescent indirectly links pairs of adolescents who are not directly linked as friends, as the social status measure. Conceptually, an adolescent with high betweenness centrality has high status because of being able to control flows of information or norms by serving as a gatekeeper between adolescents, as well by connecting adolescents from different parts of the network who are not directly connected to each other (Ennett et al., 2006). We chose this indicator of status based on Faris’s (2012) finding that betweenness centrality more strongly predicted high status, as reflected in high school yearbooks, than did other measures of centrality. Using the student directory, students were asked to identify up to five of their closest friends, starting with their best friend. Betweenness centrality was created by determining the shortest path (geodesic) between each pair of adolescents in the network and then determining the number of geodesics that include the focal adolescent. Paths are determined by friendship nominations that link adolescents together directly and indirectly. This variable was coded such that higher values reflected greater centrality, or social status (mean =1.00; STD =1.33; range =0–12.69).

Physical dating violence perpetration

Physical dating violence perpetration was assessed at both the fall and spring assessment. At the fall assessment, lifetime dating violence perpetration was assessed by asking the adolescents, “How many times have you ever used physical force against someone you were dating or on a date with (such as hitting, pushing, shoving, kicking, or assaulting them with a weapon) that was not in self-defense or play?” Response categories ranged from zero (0) to 10 times or more (4) (mean =0.13; STD =0.57; range =0–4). The percentage of dating adolescents who reported at the fall assessment having ever perpetrated physical dating violence was 6.8%. During the spring assessment, adolescents were administered a short version of the Safe Dates Physical Dating Abuse Perpetration Scale (Foshee, 1996). Adolescents were asked how often they had perpetrated six physically violent acts against someone they were dating or on a date with during the previous 3 months. They were asked to not count acts committed in self-defense or play. The six behavioral acts listed were: “pushed, grabbed, shoved, or kicked,” “slapped or scratched,” “physically twisted their arm,” “hit them with a fist or something else hard,” “beat them up,” and “assaulted them with a knife or gun.” Response categories ranged from zero (0) to 10 times or more (5). A follow-up dating violence perpetration score was created by summing and averaging the responses (mean =0.14; STD =0.60; range =0–4; Cronbach’s α=.97). The percentage of the dating adolescents who reported perpetrating any of the acts in the prior 3 months was 14.7%.

Control variables

All models controlled for sex and race of the adolescent, family structure, parent education, grade, and family aggression. Control variables were measured from the fall assessment. Sex of the adolescent was coded as 0 =girls and 1 =boys. Race was measured by two variables: one indicating black race and the other indicating a race other than white or black; white race served as the reference. Family structure was coded such that 1 =the adolescent lived with only one parent or caregiver and 0 =other family structures. Parent education was measured as the highest level of education attained by either parent, from less than high school (0) to graduate school or more (5). Adolescent grade was coded as 8th, 9th, or 10th. Family aggression was assessed by three items from Bloom’s (1985) measure of family functioning and family conflict (we fight a lot in our family, family members sometimes get so angry they throw things, and family members sometimes hit each other). Higher scores indicated higher levels of family aggression (α=.86). Analyses also controlled for the lifetime dating violence perpetration variable described above from the fall assessment to control for the temporality of relationships.

Analysis Strategy

Study hypotheses were tested using the SAS PROCESS computational macro which estimates conditional process models using a path analytic regression framework (Hayes, 2013). PROCESS allows for testing of conditional indirect effects using bootstrapping, a non-parametric method of estimating standard errors and confidence intervals for indirect effects that provides greater power for detecting the indirect effects than other methods (Hayes, 2013; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). We first examined whether baseline bullying perpetration and bullying victimization interacted to predict physical dating violence perpetration at follow-up, adjusting for all of the control variables, including the fall assessment of lifetime dating violence perpetration. Although bullying victimization and bullying perpetration were discrete variables, we modeled them as continuous variables to retain the ordinal nature of the data and modeling them as categorical (i.e., as discrete counts) would have been computationally intractable. Although prior research found that bullying was correlated with (Pepler et al., 2006) and predicted (Foshee et al., 2014) physical dating violence perpetration by both boys and girls, because Connolly et al. (2000) found that bullying perpetration was more strongly associated with dating violence perpetration for boys than girls, this model initially included interactions between bullying perpetration, bullying victimization and sex of the adolescent. None of the interactions with adolescent sex were significant and, therefore, they were dropped from the model and sex differences were not examined further.

Next, we conducted the series of models needed for testing the conditional indirect effects hypotheses. In these analyses, significant interactions between bullying perpetration and bullying victimization were probed by examining the associations between bullying perpetration and outcomes when there was no bullying victimization, when bullying victimization was at the mean (a value of 0.58), and when bullying victimization was 1 standard deviation above the mean (a value of 1.73). As recommended by Preacher et al. (2007), we also probed the interactions utilizing the Johnson-Neyman technique to identify significant regions of the moderator (bullying victimization) where the effect of bullying perpetration on the various outcomes became significant or non-significant (Johnson & Fay, 1950). The indirect effects of bullying perpetration on dating violence perpetration through the mediators were calculated at the three levels of bullying victimization (no victimization, the mean level of victimization, and at 1 standard deviation above the mean on victimization). Bias-corrected confidence intervals for the conditional indirect effects were constructed based on 5,000 bootstrap samples.

PROCESS addresses missing data through listwise deletion and the sample size for the various models therefore differed depending on the variables included in the models. We conducted analyses to determine whether there were any significant differences between (1) the sample of dating adolescents who completed the fall and spring assessments (full sample N =3,161) and (2) those who completed both of these assessments, without any missing data (complete sample N =2,414). In the complete versus the full sample of daters, there were fewer boys (complete sample—44.08%; full sample—46.98%; P =.03), more white youth (complete sample—61.31%; full sample—55.90%; P <.001), fewer black youth (complete sample—26.80%; full sample—30.97%; P <.001), and fewer single parent households (complete sample—3.40%; full sample—5.39%; P <.001). However, there were no differences in the two samples in the percentages of adolescents of race/ethnicities other than white or black, parent education, family aggression, bullying perpetration, bullying victimization, the four mediators, and baseline and follow-up dating violence.

RESULTS

Descriptive Results

Table I presents a correlation matrix of the key study variables. Bullying perpetration was significantly positively associated with all four proposed mediators and with follow-up dating violence perpetration. Bullying victimization was significantly positively associated with anger, depression, and anxiety, but was not significantly associated with betweenness centrality or follow-up dating violence perpetration. Anger, depression, and anxiety were significantly associated with follow-up dating violence, but betweenness centrality was not.

TABLE I.

Correlation Matrix of Key Study Variables (N = 2,581)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Follow-up dating violence perpetration | |||||||

| (2) Bullying perpetration | .04 | ||||||

| (3) Bullying victimization | <.01 | .37 | |||||

| (4) Anger | .14 | .11 | .09 | ||||

| (5) Depression | .11 | .09 | .08 | .61 | |||

| (6) Anxiety | .10 | .08 | .11 | .83 | .67 | ||

| (7) Betweenness centrality | −.03 | .11 | .01 | −.01 | .02 | −.01 |

Note: Bold text denotes P <0.05.

Assessment of Bullying Perpetration, Bullying Victimization, and Their Interacting effects on Physical Dating Violence Perpetration

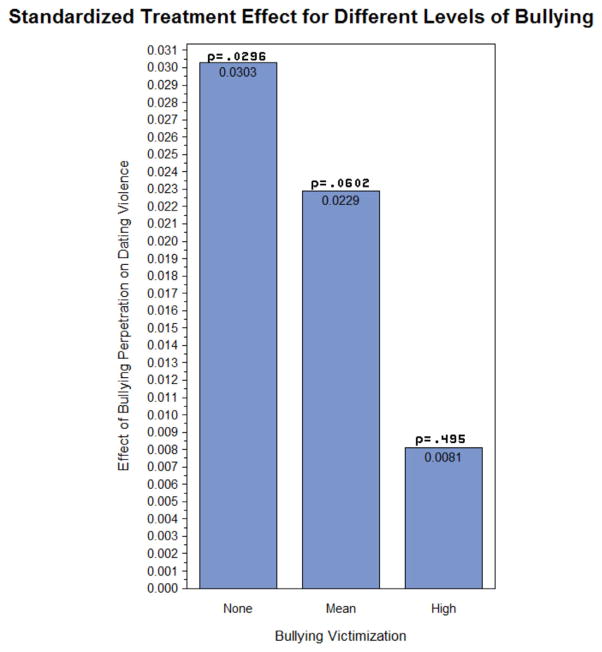

We expected that the interaction between bullying perpetration and bullying victimization would not be significant, but there would be a significant main effect of bullying perpetration on dating violence perpetration. Counter to expectations, the interaction between bullying perpetration and bullying victimization when adjusting for the control variables was statistically significant (b =−0.013; P =.0453). Bullying perpetration predicted dating violence perpetration when there was no bullying victimization (b =0.0303; P =.0296) but the association was only marginal when bullying victimization was at the mean (b =0.0229; P =.0602), and there was no significant association when bullying victimization was high (b =0.0081; P =.4950) (see Fig. 2). The Johnson-Neyman technique indicated that when the adolescent had been victimized by one or more peers, bullying perpetration did not predict physical dating violence.

Fig. 2.

Model based effect of bullying perpetration on physical dating violence perpetration at three levels of bullying victimization.

Assessment of Conditional Indirect Effects

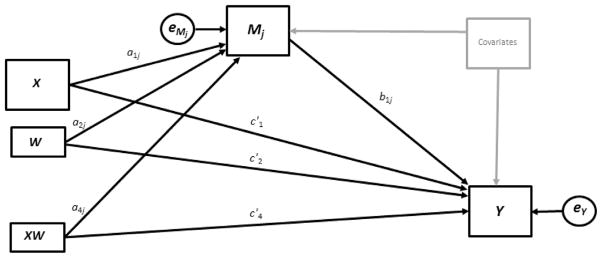

Conditional indirect effects were tested using a model that accommodated our expectations that the associations between bullying perpetration and the mediators would be moderated by bullying victimization, and our finding that the association between bullying perpetration and dating violence was moderated by bullying victimization. These specifications matched Model 8 of the SAS PROCESS macro. This statistical model is presented in Figure 3. We first tested this model with the three emotion-based mediators entered into the model simultaneously. Then, we tested the model considering betweenness centrality as the mediator.

Fig. 3.

The statistical model tested (from Hayes, 2013; p. 369). Note: X denotes the independent variable (bullying perpetration); W denotes the moderating variable (bullying victimization); XW denotes the interaction between the independent variable (bullying perpetration) and the moderator (bullying victimization); Mj denotes each mediating variable (anger, anxiety, depression, and social status); and Y denotes the outcome (follow-up dating violence perpetration). Covariates include sex and race of the adolescent (black race and other race with the reference being white), family structure, parent education, grade in school, family aggression, and baseline lifetime dating violence perpetration.

Assessment of the emotion-based mediators, conditional on bullying victimization

Table II presents parameter estimates for the effect of bullying perpetration on each of the emotion-based mediators (path a) conditional on bullying victimization. Our expectation was that bullying perpetration and bullying victimization would interact to predict emotional distress such that bullying perpetration would be associated with anger, anxiety, and depression at higher levels of bullying victimization. Table III presents parameter estimates for the unique association between each emotion-based mediator and follow-up dating violence perpetration (b paths), controlling for the other mediators in the model, baseline bullying perpetration and victimization, and the control variables. We expected that each emotion-based mediator would uniquely predict dating violence perpetration at follow-up.

TABLE II.

Association Between Bullying Perpetration, Bullying Victimization, and Their Interaction and the Proposed Emotion-Based Mediators (N =2,414)

| Anger

|

Anxiety

|

Depression

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | P | B | SE | P | B | SE | P | |

| Intercept | 1.45 | 0.13 | .0000 | 1.76 | 0.16 | .0000 | 1.29 | 0.19 | .0000 |

| Bullying perpetration (BP) | 0.04 | 0.02 | .0156 | 0.004 | 0.02 | .8721 | 0.05 | 0.03 | .0691 |

| Bullying victimization (BV) | 0.04 | 0.017 | .0248 | 0.09 | 0.02 | .0000 | 0.06 | 0.02 | .0089 |

| BP X BV | −0.01 | 0.01 | .3026 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .3609 | −0.02 | 0.01 | .0748 |

Note: Models were conducted in a multi-mediator framework and therefore each model adjusted for the other mediators. Each model also controls for sex and race of the adolescent (black race and other race, with the reference for both being white), family structure, parent education, grade in school, family aggression, and baseline assessment of lifetime dating violence perpetration.

Bold text denotes statistically significant relationships at P<.05 or lower.

TABLE III.

Association Between the Emotion-based Mediators and Follow-Up Dating Violence Perpetration, Controlling for Bullying Perpetration, Bullying Victimization and Their Interaction, and Control Variables (N =2,414)

| B | SE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.01 | 0.09 | .9434 |

| Bullying perpetration (BP) | 0.01 | 0.01 | .2850 |

| Bullying victimization (BV) | 0.00 | 0.01 | .8744 |

| BP × BV | −0.01 | 0.01 | .0711 |

| Anger | 0.05 | 0.02 | .0189 |

| Depression | 0.01 | 0.01 | .4985 |

| Anxiety | −0.02 | 0.02 | .4511 |

| Lifetime dating violence | 0.26 | 0.02 | .0000 |

| Sex | 0.06 | 0.02 | .0093 |

| Black | 0.01 | 0.03 | .6794 |

| Other | 0.04 | 0.04 | .3214 |

| Parent education | 0.00 | 0.01 | .5826 |

| Grade | 0.01 | 0.01 | .3708 |

| Family aggression | 0.02 | 0.01 | .0365 |

| Family structure | −0.02 | 0.04 | .6048 |

Bold text denotes statistically significant relationships at P <.05 or lower.

Counter to our expectations, bullying perpetration and bullying victimization did not interact to predict anger, depression, or anxiety (see Table II). Instead, there were main effects of the bullying variables on these outcomes. Bullying perpetration was significantly associated with higher levels of anger (b =0.04; P =.0156), regardless of bullying victimization, but it was not associated with anxiety (b =0.004; P =.8721) or depression (b =0.05; P =.0691) at any level of bulling victimization. Bullying victimization was significantly associated with higher levels of anger (b =0.04; P =.0248), anxiety (b =0.09; P =.0000), and depression (b =0.06; P =.0089), regardless of bullying perpetration.

Consistent with expectations, anger significantly predicted physical dating violence perpetration (b =0.05; P =.0189); however, counter to expectations, depression and anxiety did not (see Table III). In this model, the baseline assessment of lifetime dating violence perpetration (b =0.26; P =.0000) and family aggression (b =0.02; P =.0365) were positively associated with follow-up dating violence perpetration. Also, boys reported perpetrating significantly more physical dating violence at follow-up than girls (b =0.06; P =.0093).

Bootstrapped confidence intervals for the conditional indirect effects of bullying perpetration on physical dating violence perpetration through emotion-based mediators indicate that indirect effect through anger was not conditional on bullying victimization. Anger was a significant mediator of the association between bullying perpetration and dating violence perpetration when there was no bullying victimization (indirect effect =0.003; CI =0.0002–0.0080), when victimization was at the mean (indirect effect =0.002; CI =0.0003–0.0060), and when victimization was high (indirect effect =0.002; CI =0.0000–0.0057). Indirect effects of bullying perpetration on physical dating violence perpetration through depression and anxiety were not significant at any level of bullying victimization. In summary, anger mediated the effect of bullying perpetration on physical dating violence at all levels of bullying victimization, and anxiety and depression did not mediate this effect at any level of bullying victimization.

Assessment of the social status mediator, conditional on bullying victimization

Table IV presents the parameter estimates for the effect of bullying perpetration on social status (betweenness centrality; path a) conditional on bullying victimization. Our expectation was that bullying perpetration and bullying victimization would interact to predict betweenness centrality such that bullying perpetration would be associated with betweenness centrality when there was no bullying victimization. Table V presents parameter estimates for the unique association between betweenness centrality and follow-up dating violence (b path), controlling for baseline bullying perpetration and bullying victimization and the control variables. We expected that betweenness centrality would predict dating violence perpetration at follow-up.

TABLE IV.

Association Between Bullying Perpetration, Bullying Victimization, and Their Interaction on Betweenness Centrality (N =2,581)

| Betweenness Centrality

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | P | |

| Intercept | 1.61 | 0.14 | .0000 |

| Bullying perpetration (BP) | 0.14 | 0.03 | .0000 |

| Bullying victimization (BV) | −0.04 | 0.02 | .0966 |

| BP × BV | −0.04 | 0.01 | .0061 |

Note: Model controls for sex and and race of the adolescent (black race and other race, with the reference for both being white), family structure, parent education, grade in school, family aggression, and baseline assessment of lifetime dating violence perpetration.

Bold text denotes statistically significant relationships at P <.05 or lower.

TABLE V.

Association Between Betweenness Centrality and Physical Dating Violence Perpetration Controlling for Bullying Perpetration, Bullying Victimization, and Their Interaction, and the Control Variables (N =2,581)

| B | SE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.11 | 0.07 | .0898 |

| Bullying perpetration (BP) | 0.02 | 0.01 | .0452 |

| Bullying victimization (BV) | −0.00 | 0.01 | .9477 |

| BP × BV | −0.01 | 0.01 | .0386 |

| Betweenness centrality | −0.01 | 0.01 | .2008 |

| Lifetime dating violence | 0.27 | 0.02 | .0000 |

| Sex | 0.05 | 0.02 | .0367 |

| Black | 0.01 | 0.03 | .7779 |

| Other | 0.05 | 0.04 | .1932 |

| Parent education | 0.00 | 0.01 | .7458 |

| Grade | 0.01 | 0.01 | .4276 |

| Family aggression | 0.03 | 0.01 | .0016 |

| Family structure | −0.04 | 0.03 | .222 |

Bold text denotes statistically significant relationships at P <.05 or lower.

As expected, bullying perpetration and bullying victimization interacted to predict betweenness centrality (b =−0.04; P =.0061; see Table IV). However, when probing the interaction at the three levels of bullying victimization, we found that bullying perpetration was significantly positively associated with betweenness centrality when there was no bullying victimization (b =0.1658; P <.0001), when bullying victimization was at the mean (b =0.1435; P <.0001), and when bullying victimization was high (b =0.0988; P =.0002). Using the Johnson-Neyman technique we were able to determine that the association remained positive and significant up to when the adolescent had been victimized by approximately three peers, after which the association became non-significant until victimization reached approximately 12 peers (b =−0.3083; P =.05), whereupon the association switched directions and again became significant. Thus, counter to expectations, bullying perpetration was associated with higher social status even if there was also some victimization. Consistent with expectations, bullying perpetration was most strongly related to high social status when there was no victimization, and it became less strongly associated with high social status as victimization increased to a point of very high victimization (victimized by approximately 12 peers). At that point, the relationship actually reversed such that bullying perpetration was significantly associated with lower social status.

Counter to our expectations, betweenness centrality did not predict physical dating violence perpetration (b =−.01; P =.2008; see Table V). Also, the indirect effect of bullying perpetration on physical dating violence perpetration through betweenness centrality was not statistically significant at any level of bullying victimization. As noted in Table V, the interaction between bullying perpetration and bullying victimization and the main effect of bullying perpetration remained statistically significant when betweenness centrality was in the model, further suggesting that betweenness centrality does not explaining those associations. Additionally, in this model the baseline assessment of lifetime dating violence perpetration (b =0.27; P =.0000), sex of the adolescent (b =0.05; P =.0367), and family aggression (b =0.03; P =.0016) predicted follow-up physical dating violence perpetration as they did in the model that included the emotion-based variables.

In summary, although the association between bullying perpetration and betweenness centrality was conditioned by bullying victimization, counter to expectations, the indirect effect of bullying perpetration on dating violence through betweenness centrality was not conditioned by bullying victimization and was not significant at any level of bullying victimization.

DISCUSSION

We expected that bullying perpetration would predict later dating violence perpetration regardless of the level of bullying victimization. Although others have found that bullying perpetration is associated with (Connolly et al., 2000; Miller et al., 2013; Pepler et al., 2006) and predicts (Foshee et al., 2014) dating violence perpetration, no study prior to this one examined whether this effect is conditional on bullying victimization. Contrary to our expectations, we found that the bullying perpetrators at greatest risk of later dating violence perpetration were those who experienced no victimization: those who perpetrated the most dating violence were those perpetrating the greatest amount of bullying, but experiencing no bullying victimization. This was the case for both boys and girls.

We predicted that the explanations for the link between bullying perpetration and physical dating violence perpetration would be conditional on levels of bullying victimization. We expected that emotional distress (anger, anxiety, and depression) would mediate the relationship between bullying perpetration and dating violence perpetration at higher levels of bullying victimization, but that social status would mediate that relationship when there was no bullying victimization. None of these expectations were supported in the data. Instead, we found that anger mediated the association between bullying perpetration and dating violence perpetration at all levels of bullying victimization and that depression, anxiety, and social status did not mediate the association between bullying and physical dating violence perpetration at any level of bullying victimization.

No prior study has examined explanations for the link between bullying perpetration and dating violence perpetration. Our findings have implications for practice by identifying a particularly high-risk group to target in dating violence prevention efforts—adolescents who are bullying others but not experiencing bullying victimization themselves—and suggesting content on which to focus those efforts. Specifically, addressing anger among these high-risk adolescents with anger management programs may prevent the progression from bullying to dating violence. However, it may be difficult to target this specific group with dating violence prevention efforts. An alternative approach to the primary prevention of dating violence indicated by our findings is through enactment of bullying prevention programs that address anger issues. This approach also seems warranted because anger mediated the association between bullying perpetration and physical dating violence perpetration, regardless of the level of bullying victimization. Because schools are cautious about issues concerning intimate relationships, they may be more willing to implement bullying than dating violence prevention programs, since these may be viewed as less controversial (Basile, Espelage, Rivers, McMahon, & Simon, 2009).

Another important finding is that the association between bullying perpetration and social status was conditional on bullying victimization. Bullying perpetration was associated with higher social status when there was no or low amounts of bulling victimization, whereas bullying perpetration was associated with lower social status when bullying victimization was at very high levels; however, it is important to note that very few adolescents in the study reached this very high level of victimization. These findings are in line with our expectations based on prior research findings that social status is higher among bullies than other bullying involvement groups (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; Espelage & Holt, 2001; Juvonen, Graham, & Schuster, 2003; Nansel et al., 2001), and that, compared to other bullying involvement categories, bully victims are the most strongly disliked and rejected by their peers and the most socially isolated (Crick & Grotpeter 1995; Haynie et al., 2001; Pellegrini, 1998; Perren & Hornung, 2005; Schwartz, 2000; Schwartz et al., 2001; Veenstra et al., 2005). Our findings suggest that the detrimental effects on social status for those who are both perpetrators and victims of bullying occurred only when the level of victimization was very high. This finding would have been missed if we had used bullying involvement categories rather than tested interactions between continuous levels of bulling victimization and bullying perpetration. However, because of the small number of adolescents in the study at the very high levels of victimization where bullying was associated with lower social status, additional studies are needed to assess the stability of this finding.

We had expected that the association between bullying perpetration and the emotion-based mediators would vary by the level of victimization, but this was not the case. Bullying perpetration was significantly associated with anger and marginally associated with depression at all levels of bullying victimization. Thus, although bullying perpetration may be used for social gains, it clearly carries an emotional cost that is not due to co-occurring victimization. Perhaps the guilt associated with bullying or the damaged relationships that may result from the bullying produce emotional distress for the bully despite gains in status. However, our findings suggest that being a victim of bullying caries emotional costs that cross a broader spectrum of outcomes since bullying victimization was significantly positively associated with anger, depression, and anxiety, regardless of bullying perpetration. Bullying prevention programs and clinicians working with children and adolescents should incorporate consideration of the emotional toll accrued from any involvement in bullying.

Of the three emotional-distress mediators examined, only anger predicted later dating violence. Although other longitudinal studies that controlled for baseline levels of dating violence, as we did, have found that depression (Foshee et al., 2010; McCloskey & Lichter, 2003) and anxiety (Foshee et al., 2010) predict later dating violence perpetration, most studies examining associations between these indicators of emotional distress and dating violence have been cross sectional; thus the associations found in those studies could have been due to depression being a consequence or a predictor of dating violence, or both. More longitudinal studies are needed to distinguish emotional distress as a predictor from a consequence of dating violence, given the implications of that distinction for guiding primary prevention programs. The fourth potential mediator examined, social status, also did not predict physical dating violence. As described earlier, we proposed several mechanisms for why those with higher social status may be more likely to perpetrate dating violence than those with lower social status (i.e., having power to manipulate social situations; having greater access to dating partners and thus less fear of negative consequences from using violence; being thrust into dating situations when social skills are still lacking; and using abuse to tamp down potentially embarrassing dating situations). Perhaps social status does not actually lead to these conditions that could promote dating violence.

Associations between several of the control variables and physical dating violence perpetration were statistically significant. We found that lifetime dating violence, sex of the adolescent and family aggression predicted physical dating violence perpetration at follow-up in both the model that included the emotion-based indicators and in the model that included social status. That lifetime reports of dating violence perpetration at baseline predicted past 3-month dating violence perpetration at the follow-up is not surprising; autocorrelation, or the correlation between the same behavior at different time points, is often statistically significant, indicating some stability in behavior over time. We found that boys reported perpetrating significantly more dating violence than girls at the follow-up. Findings from previous research examining sex differences in the perpetration of physical dating violence have been inconsistent, with many studies reporting more perpetration by girls, some finding more perpetration by boys, and others finding no sex differences (see Foshee & Matthew, 2007 for a review). Inconsistent findings may be due to differences across studies in the measurement of dating violence, including the severity and whether perpetration in self-defense was ruled out, sample characteristics, including age and geographic location, and variation in the covariates in models. As expected, based on tenets of social learning theory (Bandura, 1973), the theory of the intergenerational transmission of violence (O’Leary, 1988), and numerous empirical findings (see Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012 for a review), family aggression predicted later dating violence perpetration. This finding provides additional evidence that interventions aimed at decreasing family aggression and conflict are warranted for the prevention of adolescent dating violence.

Although our study expectations were based on predominant findings in research on bullying involvement, there are inconsistencies in findings across that body of research. For example although, as described above, many studies have found that bully victims are more strongly disliked and rejected by their peers than are bullies, a few studies have found that there are no differences in dislike and rejection by peers between bullies and bully victims (Batsche & Knoff, 1994; Schwartz, 2000; Veenstra et al., 2005). Also, although the preponderance of research has reported more emotional distress among bully victims than bullies, others found similar levels of emotional distress among bully victims and bullies (Gini, 2008; Swearer et al., 2001). Perhaps the use of bullying involvement categories rather than the testing of interactions is responsible for some of these inconsistencies. By testing interactions between continuous measures of bullying perpetration and bullying victimization, we learned that it is the degree of bullying victimization that is paired with bullying perpetration that makes a difference in outcomes and processes, rather than whether there was any victimization or not paired with bullying. This is an important consideration for future studies interested in investigating differences in characteristics and behavior among those with varying types of involvement in bullying.

The study has several weaknesses that should be considered when interpreting the findings. The primary weakness is that although the temporality of the associations between the bullying variables and dating violence perpetration, and between the mediators and dating violence perpetration could be determined because baseline lifetime dating violence perpetration was controlled, the temporality of the associations between the bullying variables and the mediators (the a path associations) could not be determined because each of these variables were measured at the same time (the fall assessment). Thus, it is possible that emotional distress and high social status preceded rather than followed involvement in bullying. Thus, the significant indirect effect of anger may result from anger being a shared risk factor that effects both bullying and dating violence, rather from anger being on the causal path from bullying to dating violence perpetration. However, even with this interpretation of the finding, the practical implications of the finding described earlier are still relevant; addressing anger management should be a key component of bullying and dating violence primary prevention programs. Similarly, our findings that bullying perpetration was associated with higher social status (at lower levels of victimization) could also be due either to increases in social status as a result of the bullying or due to adolescents of high status being more likely to become bullies.

Although we controlled for a number of shared risk factors that could confound the association between bullying and dating violence, we did not have measures for other variables that could confound the association such as lack of empathy, need for power and control, narcissism, lack of social competence and problem solving skills, and exposure to poor parenting. Factors at outer levels of the social ecology such as going to schools that tolerate violence and living in neighborhoods that provide models of aggressive behavior should also be considered as potential confounders because each has been associated with both bullying and dating violence (Basile et al., 2009; Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim, & Sadek, 2010).

Our measures of bullying perpetration and victimization did not distinguish direct (e.g., physical violence or intimidation and verbal bullying like name calling and teasing) from indirect (e.g., behavior that is intended to harm others through spreading rumors that result in social exclusion or manipulation of relationships) forms of bullying (Faris, 2012; Faris & Felmlee, 2011). Distinguishing the types of bullying could be important given that other longitudinal studies found that direct (Foshee et al., 2014), but not indirect (Chiodo et al., 2012; Foshee et al., 2014) bullying perpetration predicted later dating violence perpetration. Another nuanced distinction to make in future bullying and dating abuse studies that we were unable to make is whether the bullying perpetration or the victimization came first for those who both bullied and were victims. The developmental processes by which victims become bullies or bullies become victims could have implications for later risk for dating violence perpetration. For example, if victims begin perpetrating out of retaliation against their tormentors, and bullies become victims because of being retaliated against by their peers (Barker, Arseneault, Brendgen, Fontaine, & Maughan, 2008; Haltigan & Vaillancourt, 2014), then, given these motivations, those who were victims first may be at less risk for perpetrating dating violence than those who were bullies first. The few studies that have examined this ordering found more evidence for victimization preceding bullying than for bullying preceding victimization (Barker et al.; Haltigan & Vaillancourt, 2014). If this is the case in our data, then that may explain why those who were both bullies and victims were not at increased risk for dating violence. As another measurement issue, given the complexity of the analyses, we focused on physical dating violence as the outcome, and did not include consideration of other forms of dating violence such as psychological or sexual dating violence. However, doing so would be worthwhile in future studies. Connolly et al. (2000) found that bullying perpetration was more strongly related to psychological than physical dating violence, and Espelage et al. (2012) found that bullying perpetration predicted sexual harassment, suggesting that bullying may also predict sexual dating violence. Finally, the study was conducted in a primarily rural county, limiting our ability to generalize the findings to more urban areas; however, it is important to note that a substantial number of adolescents live in rural areas in the United States (Gesler & Ricketts, 1992), and that both bullying (Nansel et al., 2001; Smokowski et al., 2013) and dating violence (Foshee, 1996) are prevelent among rural adolescents.

The study also had many strengths including its longitudinal design, a large sample size as required for testing interactions, a high response rate, and a general population rather than clinical sample. By using a social network approach rather than self-reports or parent/teacher/peer ratings to measure bullying, the likelihood of obtaining underestimated reports of bullying behavior was reduced. Also, not relying on self-reports of bullying behavior decreased the likelihood of producing inflated associations between the bullying variables and dating violence due to common method variance (Williams & Brown, 1994). Additionally, the likelihood of producing inflated associations between bullying and dating violence due to the targets of the bullying being dating partners was reduced by limiting reports of bullying toward and by peers of the same sex. However, the possibility of measurement redundancy between bullying and dating violence remains if adolescents were dating same sex peers, but the prevalence of same sex dating at these grades is extremely low (Mustanski et al., 2014). Additionally, the measure of physical dating violence ruled out acts perpetrated in “play” which decreases the likelihood of overestimating dating violence because “pushing and poking” courtship, which is common among adolescents (Pellegrini, 2001), is not captured. Finally, the analyses controlled for a number of shared risk factors that could produce spurious relationships between the predicted relationships.

In summary, the study extends extant research in a number of important ways. It is the first study to examine whether the effect of bullying perpetration on physical dating violence perpetration is conditional on levels of bullying victimization, and it is the first to examine explanations for the link between bullying perpetration and dating violence perpetration. Understanding which combination of bullying perpetration and bullying victimization puts adolescents at greatest risk for abusing dates, and why that combination puts adolescents at greater risk are important for informing dating violence prevention activities. Our finding that adolescents who bully but are rarely victimized by bullying are at greatest risk of later dating violence perpetration suggests that both boys and girls who are identified as bullies should be specifically targeted with dating violence prevention efforts. Our finding that anger explained why bullying perpetration was associated with later dating violence perpetration suggests that reducing anger and improving anger management skills should be key components of those prevention efforts.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute on Drug Abuse; contract grant number: R01 DA13459; contract grant sponsor: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; contract grant numbers: R49 CCV423114, 13IPA1303570, 13IPA130569.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA13459), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R49 CCV423114), and an inter-personnel agency agreement (IPA) between Dr. Foshee and the CDC (13IPA1303570) and between Dr. McNaughton Reyes and the CDC (13IPA130569). All persons who contributed to the preparation of this manuscript are included as authors.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- Alexander C, Piazza M, Mekos D, Valente T. Peers, school, and adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29:22–30. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1995;5:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J, Ireland JL, Power CL. Differences between bullies and victims, and men and women, on aggression-related variables among prisoners. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2007;46:299–322. doi: 10.1348/014466606X114083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atik G, Güneri OY. Bullying and victimization: Predictive role of individual, parental, and academic factors. School Psychology International. 2013;34:658–673. doi: 10.1177/0143034313479699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin S, Joseph S. Assessment of bully/victim problems in 8 to 11 year-olds. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 1996;66:447–456. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1996.tb01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldry AC. Bullying in schools and exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:713–732. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Aggression: A social learning analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Barker ED, Arseneault L, Brendgen M, Fontaine N, Maughan B. Joint development of bullying and victimization in adolescence: Relations to delinquency and self-harm. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(9):1030–1038. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eec98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Espelage DL, Rivers I, McMahon PM, Simon TR. The theoretical and empirical links between bullying behavior and male sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14(5):336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batsche GM, Knoff HM. Bullies and their victims: Understanding a pervasive problem in the schools. School Psychology Review. 1994;23:165–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom BL. A factor analysis of self-report measures of family functioning. Family Process. 1985;24:225–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers L, Smith PK, Binney V. Perceived family relationships of bullies, victims and bully/victims in middle childhood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1994;11:215–232. doi: 10.1177/0265407594112004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes L, Arseneault L, Maughan B, Taylor A, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children’s bullying involvement: A nationally representative longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:545–553. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819cb017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camodeca M, Goossens FA, Schuengel C, Terwogt MM. Links between social information processing in middle childhood and involvement in bullying. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29:116–127. doi: 10.1002/ab.10043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Dishion TJ, Stoolmiller M, Yoerger K. Aggression toward female partners by at-risk young men: The contribution of male adolescent friendships. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:61–73. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3(2):231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo D, Crooks CV, Wolfe DA, McIsaac C, Hughes R, Jaffe PG. Longitudinal prediction and concurrent functioning of adolescent girls demonstrating various profiles of dating violence and victimization. Prevention Science. 2012;13(4):350–359. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AH, Mayeux L. From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development. 2004;75(1):147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W, Taradash A. Dating experiences of bullies in early adolescence. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:299–310. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CR, Williams KR, Guerra NG, Kim TE, Sadek S. Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly. 2010;25(2):65. doi: 10.1037/a0020149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child development. 1995;66(3):710–722. doi: 10.2307/1131945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bolle M, Tackett JL. Anchoring bullying and victimization in children within a five-factor model-based person-centred framework. European Journal of Personality. 2013;27:280–289. doi: 10.1002/per.1901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dukes RL, Stein JA, Zane JI. Effect of relational bullying on attitudes, behavior and injury among adolescent bullies, victims and bully-victims. The Social Science Journal. 2009;46:671–688. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2009.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Faris R, Foshee VA, Cai L, DuRant RH. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:159–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00127.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Cai L, Reyes HLM, DuRant R. The social ecology of adolescent alcohol misuse. Child Development. 2008a;79:1777–1791. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Faris R, Hipp J, Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Cai L. Peer smoking, other peer attributes, and adolescent cigarette smoking: A social network analysis. Prevention Science. 2008b;9:88–98. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0087-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Holt MK. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2001;2(2–3):123–142. doi: 10.1300/J135v02n02_08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Swearer SM. Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review. 2003;32:365–383. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Wasserman S, Fleisher MS. Social networks and violent behavior. In: Flannery DJ, Vazsonyi AT, Waldman ID, editors. The Cambridge handbook of violent and aggressive behavior. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 450–454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Basile KC, Hamburger ME. Bullying perpetration and subsequent sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falb KL, McCauley HL, Decker MR, Gupta J, Raj A, Silverman JG. School bullying perpetration and other childhood risk factors as predictors of adult intimate partner violence perpetration. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2011;16:890–894. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris R, Felmlee D. Status struggles: Network centrality and gender segregation in same- and cross-gender aggression. American Sociological Review. 2011;76:48–73. doi: 10.1177/0003122410396196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faris R. Aggression, exclusivity, and status attainment in interpersonal networks. Social Forces. 2012;90:1207–1235. doi: 10.1093/sf/sos074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, DeWall CN, Slotter EB, Oaten M, Foshee VA. Self-regulatory failure and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:483–499. doi: 10.1037/a0015433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee V. Gender differences in adolescent dating abuse prevalence, types, and injuries. Health Education Research. 1996;11:275–286. doi: 10.1093/her/11.3.275-a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Matthew RA. Adolescent dating abuse perpetration: A review of findings, methodological limitations and suggestions for future research. In: Flannery D, Vazonsyi A, Waldman I, editors. The cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 431–449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Reyes HLM. Dating Abuse: prevalence, consequences, and predictors. In: Levesque JRR, editor. Encyclopedia of adolescence. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 602–615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee V, Bauman K, Linder F. Family violence and the perpetration of adolescent dating violence: Examining social learning and social control processes. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:331–342. doi: 10.2307/353752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Reyes HLM, Ennett ST. Examination of sex and race differences in longitudinal predictors of the initiation of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma. 2010;19:492–516. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2010.495032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, Ennett ST, Suchindran C, Mathias JP, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Benefield TS. Risk and protective factors distinguishing profiles of adolescent peer and dating violence perpetration. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Benefield TS, Reyes HLM, Ennett ST, Faris R, Chang LY, Suchindran CM. The peer context and the development of the perpetration of adolescent dating violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:471–486. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9915-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Basile KC, Chang L, Faris R, Ennett ST. Bullying as a longitudinal predictor of adolescent dating violence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredland NM. Sexual bullying: Addressing the gap between bullying and dating violence. Advances in Nursing Science. 2008;3(2):95–105. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000319560.76384.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou SN, Stavrinides P. Bullies, victims and bully-victims psychosocial profiles and attribution styles. School Psychology International. 2008;29:574–589. doi: 10.1177/0143034308099202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gesler W, Ricketts T. Health in rural America: The geography of health care services and delivery. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gini G. Associations between bullying behaviour, psychosomatic complaints, emotional and behavioural problems. Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health. 2008;44:492–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltigan JD, Vaillancourt T. Joint trajectories of bullying and peer victimization across elementary and middle school and associations with symptoms of psychopathology. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(11):2426–2436. doi: 10.1037/a0038030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Nansel T, Eitel P, Crump AD, Saylor K, Yu K, Simons-Morton B. Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at-risk youth. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:29–49. doi: 10.1177/0272431601021001002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isolan L, Salum GA, Osowski AT, Zottis GH, Manfro GG. Victims and bully-victims but not bullies are groups associated with anxiety symptomatology among Brazilian children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;22:641–648. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0412-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LR, Brett JM. Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1984;69:307. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, Fay LC. The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika. 1950;15:349–367. doi: 10.1007/BF02288864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Graham S, Schuster MA. Bullying among young adolescents: The strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6):1231–1237. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpelä M, Rantanen P, Rimpelä A. Bullying at school—An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23(6):661–674. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witness to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(2):339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Lichter EL. The contribution of marital violence to adolescent aggression across different relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:390–412. doi: 10.1177/0886260503251179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menesini E, Modena M, Tani F. Bullying and victimization in adolescence: Concurrent and stable roles and psychological health symptoms. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2009;170:115–134. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.170.2.115-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Williams J, Cutbush S, Gibbs D, Clinton-Sherrod M, Jones S. Dating violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: Longitudinal profiles and transitions over time. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:607–618. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9914-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Birkett M, Greene GJ, Rosario M, Bostwick W, Everett BG. The association between sexual orientation identity and behavior across race/ethnicity, sex, and age in a probability sample of high-school students. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:237–244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Myint-U A, Duran R, Agronick G, Wilson-Simmons R. Middle school aggression and subsequent intimate partner physical violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(5):693–703. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9086-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Physical aggression between spouses: A social learning theory perspective. In: Van Hasselt VB, Morrison RL, editors. Handbook of Family Violence. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing; 1988. pp. 31–55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Aggression in the schools: Bullies and whipping boys. Oxford, England: Hemisphere; 1978. [Google Scholar]