Abstract

Patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) tend to show signs of a relatively increased inflammatory state suggesting that activation of the immune system may contribute to the development of PTSD. In the present study, we tested whether activation of the innate immune system can disrupt acquisition or recall of auditory fear extinction using an animal model of PTSD. Male adolescent rats received auditory fear conditioning in context A. The next day, an intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 100 μg/kg) prior to auditory fear extinction in context B impaired acquisition and recall of extinction. LPS (100 μg/kg) given after extinction training did not impair extinction recall suggesting that LPS did not affect consolidation of extinction. In contrast to cued fear extinction, contextual fear extinction was not affected by prior injection of LPS (100 μg/kg). Although LPS also reduced locomotion, we could dissociate the effects of LPS on extinction and locomotion by using a lower dose of LPS (50 μg/kg) which impaired locomotion without affecting extinction. In addition, 15 hrs after an injection of 250 μg/kg LPS in adult rats, extinction learning and recall were impaired without affecting locomotion. A sub-chronic treatment with candesartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, prevented the LPS-induced impairment of extinction in adult rats. Our results demonstrate that activation of the innate immune system can disrupt auditory fear extinction in adolescent and adult animals. These findings also provide direction for clinical studies of novel treatments that modulate the innate immune system for stress-related disorders like PTSD.

Keywords: amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, angiotensin, extinction, lipopolysaccharide

INTRODUCTION

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a severe stress disorder that can develop after experiencing significant physical and/or psychological trauma (Jakovljević et al., 2012). Current treatments for PTSD produce inconsistent results (Asnis et al., 2004; Cohen et al., 2011; Rosen et al., 2013). Therefore, the search for novel and effective pharmacological treatment is of major interest. Patients with PTSD show lower levels of peripheral cortisol (Bierer et al., 2006), increased glucocorticoid sensitivity (Rohleder et al., 2004), and altered diurnal rhythms of cortisol levels (de Kloet et al., 2006; Yehuda et al., 2005) leading to a clinical pattern of low HPA axis activity.

By activating glucocorticoid receptors in immune cells, cortisol modulates gene transcription to decrease inflammation (Adcock et al., 2004). Since cortisol has anti-inflammatory effects, the reduced cortisol levels in PTSD could lead to a relatively increased inflammatory state in these patients. Consistent with this possibility, previous studies found that patients with PTSD also have increased expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Gill et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2012; Lindqvist et al., 2014; Rohleder et al., 2004; Sánchez-Lemus et al., 2009; van Zuiden et al., 2012). It has been hypothesized that increased inflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of PTSD symptoms such as re-experiencing the traumatic event (Jones and Thomsen, 2013). In support of this hypothesis, the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α positively correlate with the severity of PTSD symptoms (Gola et al., 2013). However, it is not clear whether an inflammatory state leads to PTSD or whether PTSD causes an inflammatory state.

One possibility is that the inflammatory state contributes to the impaired fear extinction seen in patients with PTSD (Milad et al., 2009; Schelling et al., 2006). In this paper, we directly tested whether activating the innate immune response with the endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) affects acquisition or recall of auditory or contextual fear extinction in rats. LPS induces macrophages to produce inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Dantzer et al., 2008; Fujihara et al., 2003). After peripheral injection of LPS, increases in these inflammatory cytokines occur in fear-related brain structures such as the amygdala (Prager et al., 2013), the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Yang et al., 2013), and the hippocampus (Kranjac et al., 2012).

The renin-angiotensin pathway promotes inflammation (Phillips and Kagiyama, 2002) through angiotensin II stimulation of the angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor (Nishimura et al., 2000; Savoia and Schiffrin, 2007). A recent study showed that the AT1 receptor blocker (ARB) candesartan reduced the acute brain inflammation induced by LPS (Benicky et al., 2011). In the present study, we examined whether activation of the innate immune system with LPS affects fear extinction and whether candesartan could reverse the effects. We found that intraperitoneal injection of LPS impairs auditory fear extinction in adolescent and adult male rats and that sub-chronic treatment with candesartan prevents the LPS-induced impairment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Ponce Health Sciences University in compliance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (28–30 days or 60–70 days postnatal) were transported from the Ponce Health Sciences University colony to a satellite facility nearby where they were housed in transparent polyethylene cages inside a negative-pressure Biobubble (Colorado Clean Room, Ft. Collins, CO). Rats were maintained on a 12/12 hr light/dark schedule with free access to food (standard laboratory rat chow) and water.

Behavioral apparatus

Rats were fear conditioned in a chamber of 25 × 29 × 28 cm (Context A) with aluminum and Plexiglas walls (Coulbourn Inst., Allentown, PA). The floor consisted of stainless steel bars that could be electrified to deliver a mild shock and illumination was provided by a single overhead light. Rats were extinguished and tested in a hexagonal chamber (Context B). A citric scent filled the chamber and the illumination color was changed to accentuate a different context. The chambers had speakers mounted on the outside wall and were situated inside a sound-attenuating box (Med Associates, Burlington, VT) with a ventilating fan, which produced an ambient noise level of 60 dB. The conditioned stimulus (CS) was a 4 kHz tone with duration of 10 seconds and an intensity of 80 dB. The unconditioned stimulus (US) was a 0.44 mA scrambled footshock, 0.5 sec in duration, which co-terminated with the tone during the conditioning phase. Between sessions, floor trays and shock bars were cleaned with soapy water and the chamber walls were wiped with a damp cloth. Behavior was recorded with digital video cameras (Micro Video Products, Ontario, Canada).

Fear conditioning and extinction and drugs

A Pavlovian fear conditioning paradigm was used to model PTSD behavior in rats. For auditory fear conditioning, 30 day-old adolescent rats received 3 tone-shock pairings in context A (Conditioning phase) on day 1. After matching for equivalent levels of freezing, conditioned rats were divided into a saline group and a LPS group. On day 2, rats received an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of LPS (Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5; Sigma- Aldrich, St Louis, MO; 50 or 100 μg/kg) or saline 1.5 or 3 hours prior to fear extinction. Fear extinction training consisted of 30 tone-alone trials of 10 seconds each in a novel chamber designated as context B. Twenty-four hours later, all rats were tested for fear expression with a 2 minute tone-alone presentation in context B.

To test the effect of LPS on contextual fear extinction, adolescent rats received 3 tone-shock pairings (conditioning phase) on day 1. The following day they received an i.p. injection of LPS (100 μg/kg) or saline 3 hours prior to fear extinction. During fear extinction training rats were exposed to the original conditioning chamber for 5 min without tones. On day 3 all rats were exposed to the same context again for 5 min to measure recall of fear extinction.

To avoid the locomotor effects of the LPS injections from interfering with quantification of fear, the above protocols were modified in the experiments done with young adult P60 rats. On day 1, the P60 rats received auditory-cue fear conditioning as described above. On day 2, the P60 rats received an i.p. injection of LPS (250 μg/kg) or saline. This dose has been previously shown to impair memory in adult rodents even when tested 24 hrs later (Haba et al., 2012). The P60 rats underwent extinction training as described above 15 hrs after the LPS or saline injection and were tested for fear expression 24 hrs later.

Two different groups of rats received the same fear conditioning on day 1. On day 2, rats received an i.p. injection of LPS (250 μg/kg) or saline. On day 3, 15 hrs after the LPS/Saline injection, rats were exposed to the same conditioning context for 5 min to induce contextual fear extinction. On day 4, rats were re-exposed to the same context again for 5 min to test for extinction memory.

To evaluate whether an ARB could modulate the effects of LPS on extinction memory, adult rats were randomly assigned to either the candesartan or vehicle groups. On day 1, the rats received the designated daily i.p. injection of vehicle or the AT1 receptor antagonist candesartan (Tocris, Bristol, UK) at a dose of 1 mg/kg in 99.9% dimethyl sulfoxide and saline. On day 2, rats received auditory fear conditioning 2 hours after their daily injection of candesartan or vehicle. On day 3, rats were treated with candesartan or vehicle and given an i.p. injection of LPS 250 ug/kg two hours later. 15 hours later on day 4, rats underwent extinction training in context B two hours after receiving their daily injection of vehicle or candesartan. Extinction memory recall was tested on the fifth day in context B. To evaluate whether candesartan could modulate extinction in the absence of inflammation, the protocol was repeated and the rats received an injection of saline instead of LPS on day 3.

Open field

Ten minutes before rats began extinction training, they were put in an open field test for 5 min to evaluate LPS effects on locomotion (velocity) and anxiety (time in center). Movement was measured by photosensors and analyzed using a computerized video tracking system (Ethovision XT 8.5, Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands).

Statistical analysis

The percent of time spent freezing (Blanchard and Blanchard, 1972) was used as a measure of conditioned fear. Freezing is the cessation of all movements except respiration. The total time spent freezing during the 10 sec tone was analyzed using commercial software (FreezeScan; Clever Systems). Student’s t-test and repeated measures ANOVA (STATISTICA, Statsoft, Tulsa, OK) were used to analyze the behavioral data. Following a significant main effect, post-hoc tests were performed with Tukey tests. Values are reported as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.).

RESULTS

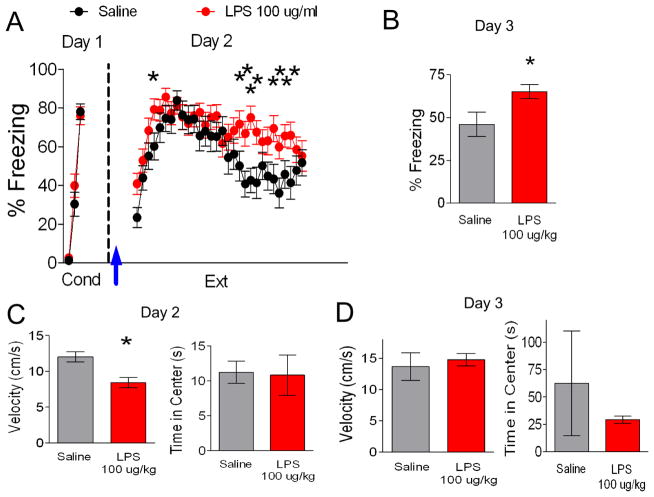

To begin to understand the effects of inflammation on fear extinction, we first determined whether activation of the innate immune response by peripheral administration of LPS affects auditory fear extinction. Since fear extinction memory in adolescent rats is less robust than in adult rats (McCallum et al., 2010; Pattwell et al., 2012), extinction during adolescence could be particularly sensitive to the effects of inflammation. Therefore, the first sets of experiments were performed with adolescent rats. On day 1, rats received 3 tone-shock pairings and were separated into two groups matched for similar freezing to the third conditioning tone (LPS 76% freezing, Saline 78% freezing, t(48) = 0.34, p = 0.74). The following day, rats received an i.p. injection of saline or LPS (100 μg/kg) 1.5 or 3 hours prior extinction training (30 tones), since increases in inflammatory cytokines are first seen in the amygdala two hours after i.p. injection of LPS (Engler et al., 2011). LPS-injected rats showed impaired acquisition of fear extinction (Figure 1A). A repeated-measures ANOVA (Trial × Drug) across the extinction phase on day 2 revealed a main effect of drug (F(1,48) = 4.34, p = 0.04) and a significant Trial × Drug interaction (F(29,1392) = 1.79, p = 0.01). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that LPS-injected rats froze significantly more than saline-injected rats during trial 4 (p = 0.04), trials 19 to 22 (p < 0.02), and from trials 25 to 28 (p < 0.04) of extinction suggesting that LPS impaired acquisition of extinction. As shown in Figure 1B, the LPS-injected group also showed more freezing behavior during the recall of extinction on day 3 (t(48) = −2.43, p = 0.02) suggesting that LPS impaired extinction memory.

Figure 1. An injection of LPS (100 ug/kg) before fear extinction disrupts extinction recall.

A. On day 1, rats (P30) were fear conditioned with three tone-shock pairings in context A and separated in two different groups (saline, n = 24; LPS, n = 20). On day 2, rats were given extinction training in a novel context B. Arrow indicates injection of LPS or saline 1.5 or 3 hrs before extinction. B. Freezing response to a test tone in context B on day 3. C. An open field test given just before extinction showed that LPS reduced locomotion but did not affect anxiety. D. An open field test performed 24 h after extinction training showed no significant effects on locomotion or anxiety (saline, n = 12; LPS, n = 12). Data represent means ± SEM. *p < 0.05

LPS can induce sickness behavior including reduced locomotion (Cunningham and Sanderson, 2008) which could confound our analysis of fear. Therefore, we also assessed the effects of LPS on locomotion and anxiety-like behavior in an open field test 10 mins before extinction training on day 2. As indicated in Figure 1C, the LPS-injected group moved slower than their saline-injected counterparts (Saline 12 ± 0.7, LPS 8 ± 0.7, t(41) = 3.57, p = 0.001) indicating that the increase in freezing during extinction in the LPS-injected rats could be due to reduced locomotion rather than fear of the tone. In contrast, both groups spent an equal amount of time exploring the center of the open field (t(41) = 0.11, p = 0.91) indicating that LPS did not affect the anxiety levels (Figure 1C). Since we also saw more freezing in the LPS-injected animals during extinction recall, we tested whether LPS affects locomotion or anxiety 24 hrs later. As shown in Figure 1D, 100 ug/kg LPS did not affect locomotion (t(10) = −0.45, p = 0.66) or time spent in the center of the open field (t(10) = 0.69, p = 0.50) 24 hrs later. Thus the increased freezing of the LPS-injected animals during extinction recall was not due to lingering effects on locomotion.

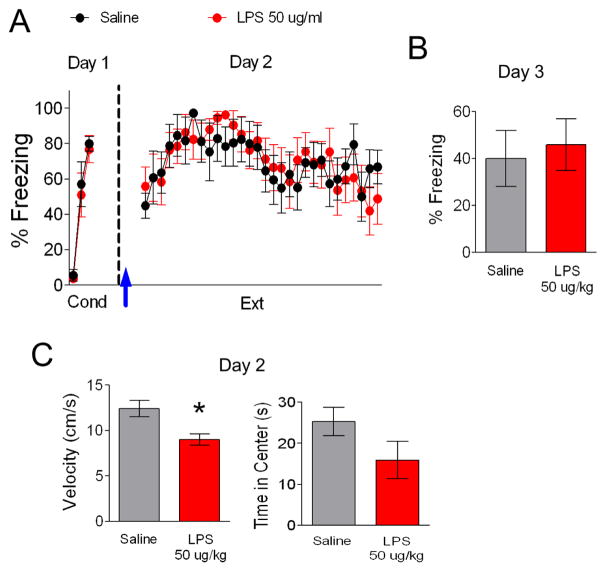

To further assess whether the effects on locomotion and extinction could be dissociated, we used a lower dose of LPS (Figure 2). As in the previous experiment, on day 1, rats received 3 tone-shock pairings and were separated into two groups matched for similar freezing to the third conditioning tone (Figure 2A; LPS 77% freezing, Saline 80% freezing, t(13) = 0.34, p = 0.74). The following day, rats were injected with saline or LPS (50 μg/kg) 3 hours prior extinction training. A repeated-measures ANOVA across the extinction phase on day 2 discerned no main effect between groups (F(1,15) =.01, p = 0.93) and no interaction between trial and drug (F(29,435) = 0.89, p = 0.64). Also, both groups showed similar freezing during extinction recall on day 3 (Figure 2B; t(13) = −0.68, p = 0.51). In addition, we examined the effect of this dose of LPS on locomotion 10 mins prior to extinction training on day 2 (Figure 2C). Although 50 ug/kg LPS did not affect fear extinction, this dose did reduce locomotion (Saline 12.4 ± 0.9, LPS 9.0 ± 0.6, t(12) = 3.07, p = 0.01) indicating that the effects of LPS on fear extinction and locomotion are dissociable. Furthermore, the 50 and 100 ug/kg doses of LPS produced similar effects on locomotion (LPS 50, 9.0 cm/s; LPS 100, 8.4 cm/s; t(25) = 0.45, p = 0.66) indicating that the 100 ug/kg dose did not further impair locomotion. As with the 100 ug/kg dose, 50 ug/kg LPS did not affect anxiety-like behavior (Figure 2C, t(12) = 1.64, p = 0.13).

Figure 2. LPS (50 ug/kg) injected before fear extinction does not disrupt extinction recall.

A. Lower dose of LPS (50 ug/kg) did not significantly affect acquisition or (B) recall of fear extinction. Arrow indicates injection of LPS or saline 3 hrs before extinction. C. This dose of LPS reduced locomotion but did not affect anxiety. Data represent means ± SEM (saline, n = 18; LPS, n = 18). *p < 0.05

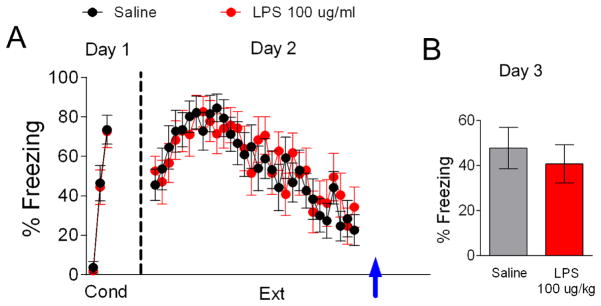

To test whether LPS impairs consolidation of auditory fear extinction memory, rats were injected with either LPS 100 μg/kg or saline immediately after extinction training on day 2 (Figure 3). On the first day rats received fear conditioning and were separated into two groups matched for similar freezing to the third conditioning tone. Rats showed no significant difference in fear acquisition between groups (Figure 3A; LPS 73% freezing, Saline 74% freezing, t(22) = 0.08, p = 0.94). On day 2 rats underwent extinction training and were immediately injected with LPS 100 μg/kg or saline at the end of the training session. A repeated-measures ANOVA across the extinction phase on day 2 revealed no significant main effect of group (F(1,22) = 0.04, p = 0.85) and no interaction between trial and group (F(29,638) = 0.84, p = 0.71) showing that both groups acquired fear extinction. As shown in Figure 3B, both groups showed similar recall of extinction on day 3 suggesting that LPS does not disrupt consolidation of fear extinction (t(22) = 0.27, p = 0.79).

Figure 3. LPS (100 ug/kg) injected after extinction does not affect extinction recall.

A. Behavior of groups before injecting LPS after extinction training on day 2 (arrow). B. Post-extinction injection did not affect extinction recall on day 3. Data represent means ± SEM (saline, n = 12; LPS, n = 12).

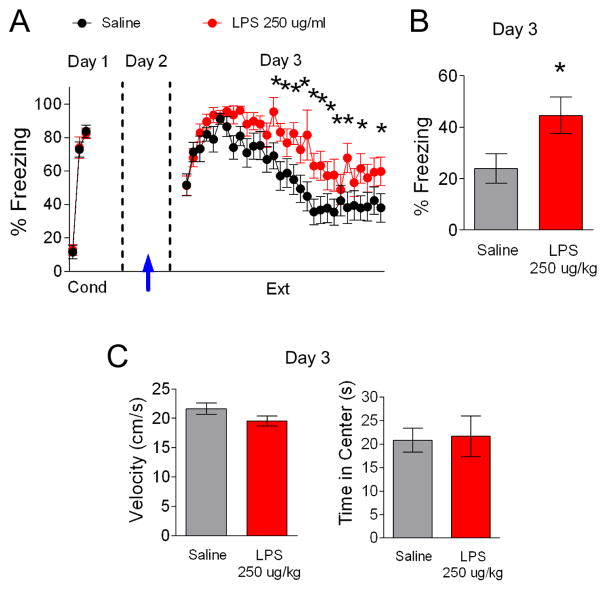

Since our experiments up to this point were done with adolescent rats and adolescent rats show less robust fear extinction (Kim et al., 2011), we next tested whether LPS also disrupts fear extinction in adult rats. To enhance the dissociation between LPS effects on locomotion and extinction, a different behavioral protocol was employed with a higher dose of LPS. We chose this protocol based on data showing that 250 ug/kg LPS produces behavioral effects without affecting locomotion between 10 and 24 hrs after LPS injection in mice (Haba et al., 2012). On the first day adult rats received cued fear conditioning and were separated into two groups matched for similar freezing to the third conditioning tone (Figure 4A; LPS 82% freezing, Saline 84% freezing, t(32) = 0.42, p = 0.68). The following day, rats were injected with saline or LPS (250 μg/kg) 15 hours prior to extinction training. As shown in Figure 4A, LPS-injected rats showed impaired acquisition of fear extinction. A repeated-measures ANOVA (Trial × Drug) across the extinction phase on day 3 revealed a main group difference (F(1,34) = 6.63, p = 0.01). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that LPS-injected rats froze significantly more than saline-injected rats during trials 14–15, 17–21, 23, 25, 27 and 30 (p < 0.04) suggesting that LPS impaired acquisition of extinction. As shown in Figure 4B, the LPS-injected group also showed more freezing behavior during the recall of extinction on day 4 (t(32) = −2.57, p = 0.02) indicating that extinction memory was impaired. This dose of LPS did not affect locomotion (t(32) = 1.13, p = 0.27) or time spent in the center of the open field (t(32) = −0.31, p = 0.76) measured 10 min prior to extinction training on day 3 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. An injection of LPS (250 ug/kg) 15 hrs prior extinction disrupts fear extinction recall.

A. On day 1, rats (P60) were fear conditioned with three tone-shock pairings in context A and separated in two different groups (saline, n = 18; LPS, n = 18). On day 2, rats received an LPS injection (arrow). 15 hrs later on day 3, rats were given extinction training in a novel context B. B. On day 4, the LPS-injected group froze more in response to a test tone in context B. C. Open field test performed before extinction training on day 3 showed no effect of LPS on locomotion or anxiety. Data represent means ± SEM. *p < 0.05

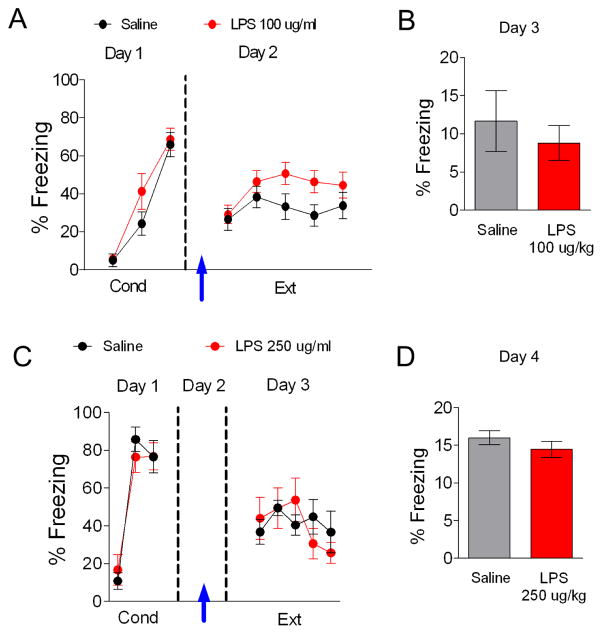

Taken together our results suggest that LPS disrupts acquisition of cued fear extinction. Next we tested whether peripheral administration of LPS also disrupts hippocampal-based contextual fear extinction in adolescent rats. On day 1 adolescent rats received fear conditioning with 3 tone-shock pairings and were separated into two groups matched for similar freezing to the third conditioning tone (Figure 5A; LPS 69% freezing, Saline 64% freezing, t(34) = −0.32, p = 0.76). On day 2, the groups received an i.p. injection of 100 μg/kg LPS or saline and were placed in the original conditioning context for 5 minutes for contextual fear extinction. A repeated measures ANOVA across the extinction phase revealed no significant main effect of drug (F(1,34) = 2.48, p = 0.13). The next day, both groups showed similar recall of contextual fear extinction (Figure 5B; t(34) = 0.62, p = 0.54).

Figure 5. LPS does not disrupt contextual fear extinction.

A. LPS (100 ug/kg) injection 3 hrs prior to contextual fear extinction on day 2 (arrow) did not affect recall of contextual fear extinction in adolescent rats (B) (saline, n = 18; LPS, n = 18). C. LPS (250 ug/kg) injection 15 hrs prior contextual fear extinction on day 2 (arrow) did not affect recall in adult rats (D). Data represent means ± SEM (saline, n = 6; LPS, n = 6).

To test whether LPS affects contextual fear extinction in adult rats, P60 rats received fear conditioning with 3 tone-shock pairings and were separated into two groups matched for similar freezing to the third conditioning tone (Figure 5C; LPS 57% freezing, Saline 58% freezing, t(10) = −0.02, p = 0.49). The following day, rats were injected with saline or LPS (250 μg/kg). On day 3, 15 hours later, rats were exposed to the original conditioning context for 5 minutes to induce contextual fear extinction. A repeated measures ANOVA across the extinction phase revealed no main effect of drug (F(29,986) = 1.1806, p = 0.24). The next day, both groups also showed similar recall of contextual fear extinction (Figure 5D; t(10) = 1.76, p = 0.11).

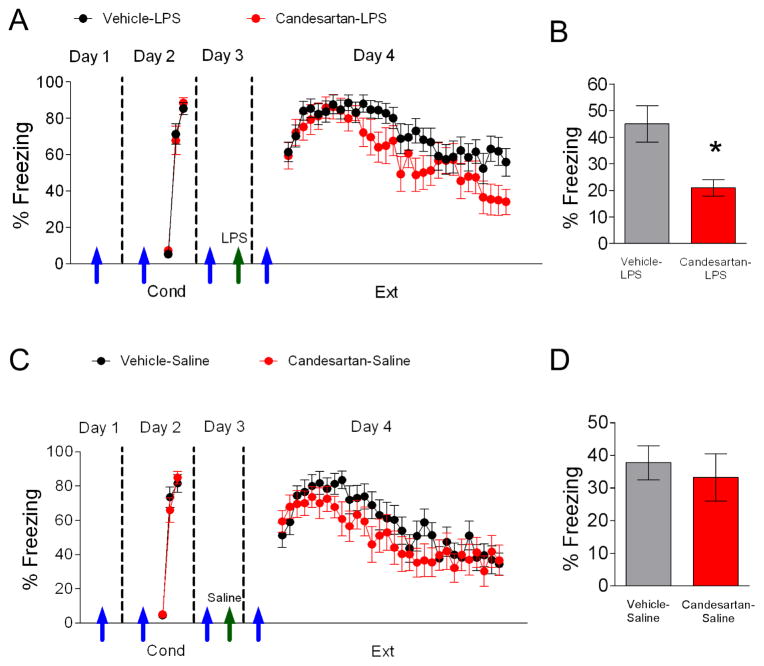

Since the ARB candesartan reduces LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in various brain structures (Benicky et al., 2011), we tested whether sub-chronic treatment with candesartan (4 daily i.p. injections; 1 mg/kg in 50% dimethyl sulfoxide and saline) would prevent the observed impairment on extinction learning and memory. On the first day, rats received candesartan (1 mg/kg) treatment or vehicle (Figure 6A). On day 2 rats received auditory fear conditioning 2 hours after treatment with candesartan or vehicle (Figure 6A; vehicle-LPS 85% freezing, candesartan-LPS 88% freezing, t(35) = −0.62, p = 0.54). The following day, rats received an injection of candesartan or vehicle and 2 hours later were injected with saline or LPS (250 μg/kg). 15 hours later on day 4, rats underwent extinction training in context B two hours after receiving their daily injection of vehicle or candesartan. Extinction memory recall was tested on the fifth day in context B. As shown in Figure 6A, rats in the Vehicle-LPS group showed impaired acquisition of fear extinction. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that rats in the Vehicle-LPS group froze significantly more than rats treated with candesartan during trials 28–30 (p < 0.05) suggesting that candesartan prevents the LPS-induced impaired acquisition of extinction. The candesartan-LPS group also showed less freezing behavior during extinction recall on day 5 (t(35) = 2.64, p = 0.01) compared to rats in the vehicle-LPS group (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Candesartan prevents LPS-induced impairment of fear extinction.

A. Pretreatment of adult rats with candesartan (blue arrows) prevented the impairment in acquisition of extinction caused by injection of LPS (green arrow; 250 ug/kg). B. Candesartan also enhanced recall of fear extinction (vehicle-LPS, n= 23; candesartan-LPS, n = 14). C–D. Candesartan by itself did not enhance extinction training nor recall of extinction (vehicle-saline, n = 19; candesartan-saline, n = 16). Data represent means ± SEM. *p < 0.05

Next we tested whether candesartan could enhance extinction training and recall in the absence of inflammation. On day 1, rats received candesartan treatment or vehicle (Figure 6C). The following day rats received cued conditioning 2 hours after treatment with candesartan and were then separated into two groups matched for similar freezing to the third conditioning tone (Figure 6C; vehicle-saline 81% freezing, candesartan-saline 84% freezing, t(33) = −0.51, p > 0.05). On day 3, rats received candesartan treatment or vehicle and 2 hours later were injected with saline 15 hours prior to extinction training. No significant differences were found between groups during acquisition of fear extinction on day 4 (Figure 9C, F(1,29) = 1.47, p > 0.05). Also, no differences were found between both groups during the recall of extinction on day 5 (Figure 6D, t(33) = 0.52, p = 0.61).

DISCUSSION

Accumulating evidence suggests that inflammation plays a role in PTSD (Lindqvist et al. 2014; Pace and Heim, 2011; Pace et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2011; von Känel et al., 2007; Zieker et al., 2007). In the present study, we found that activating peripheral inflammation with LPS impairs acquisition and recall of auditory fear extinction in adolescent and adult rats. The lack of effect of LPS given post-extinction suggests that LPS disrupts acquisition rather than consolidation of the auditory fear extinction memory. LPS did not affect contextual extinction, suggesting the observed impairment in auditory fear extinction was not related to disruption of hippocampal function. Of clinical interest, a four day treatment with candesartan was able to prevent LPS from impairing fear extinction learning and memory.

Previous studies found that LPS disrupts fear memory consolidation (Gonzalez et al., 2013; Kranjac et al., 2012; Pugh et al., 1998). Our findings suggest that activation of the immune system impairs acquisition of fear extinction rather than consolidation of extinction memory. Our results showed that LPS-treated rats froze significantly more across several extinction training trials and showed impaired recall of extinction. Additionally, post-extinction training administration of LPS did not affect consolidation of extinction memory. This is consistent with a previous study showing that LPS impaired training and probe sessions in the Morris water maze task (Choi et al., 2012).

Although LPS induced sickness behavior which reduced locomotor activity, LPS impaired fear extinction independent of its effects on locomotion. First, locomotor activity was reduced by a dose of LPS that did not disrupt fear extinction training or recall indicating that the effects on locomotion and fear extinction can be dissociated. In addition, extinction learning was impaired 15 hours after administration of LPS when locomotion was not affected. Furthermore, LPS impaired extinction recall 24 hours later when LPS’ effect on locomotion had dissipated.

Although LPS disrupts consolidation of hippocampal-dependent memory tasks such as the water maze, inhibitory avoidance, and contextual fear conditioning (Pugh et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2007; Yin et al., 2013), our findings suggest that innate immune activation impairs acquisition of auditory fear extinction through a mechanism that does not involve disruption of the hippocampus. PTSD has been associated with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in the blood (Andrews and Neises, 2012). Injection of LPS increases TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in critically relevant fear-related structures such as the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (Benicky et al., 2011). It is possible that TNF-α and IL-1β impair extinction learning by increasing activation of the central amygdala, since this structure increases conditioned fear (LeDoux et al., 1988; McNally et al., 2011) and shows heightened activity 24 hours after LPS injection (Haba et al., 2012).

Another potential mechanism mediating the impaired extinction induced by LPS is reduced activity in the infralimbic (IL) portion of the mPFC, which has been implicated in extinction learning and recall (Godsil et al., 2013; Quirk and Mueller, 2008; Sierra-Mercado et al., 2011). IL inhibits conditioned fear responses through projections onto inhibitory neurons in the amygdala which leads to reduced activity in the central amygdala and less fear expression (Amano et al., 2010; Milad and Quirk, 2012; Orsini and Maren, 2012). Therefore, increased cytokine expression could disrupt fear extinction by increasing activity in the amygdala or decreasing activity in IL.

One of the most important findings in our study was that treatment with the AT1 receptor antagonist candesartan prevented the LPS-induced impairment of acquisition and recall of extinction memory. Since ARBs modulate LPS-induced inflammation by blocking AT1 receptors and inhibiting NF-κB activity (Miyoshi et al., 2008), candesartan could be enhancing acquisition of extinction through reduced cytokine-induced NF-κB activity in fear extinction related structures. Since ARBs also exhibit partial peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) agonistic effects and cognitive enhancement beyond blockade of AT1 receptors (Kurtz and Klein, 2009; Min et al., 2012; Schupp et al., 2004; Tsukuda et al., 2009), candesartan could also enhance fear extinction through activation of the PPAR-γ pathway. Regardless of the mechanism, ARBs appear to be particularly useful for enhancing extinction of aversive memories and may explain why trauma-exposed patients taking ARBs had lower risk of PTSD symptoms (Khoury et al., 2012).

A previous study showed that chronic treatment with the ARB losartan enhanced extinction training and consolidation of extinction memory (Marvar et al., 2014). In the present study, extinction training and recall were not enhanced by treatment with candesartan alone. We used 1 mg/kg of candesartan because this dose reduces brain inflammation induced by LPS (Benicky et al., 2011); however, it is possible that a larger dose could facilitate extinction. Further experimentation is required to determine whether the dose of candesartan or other experimental differences account for the discrepancy.

In this study we did not directly measure cytokine levels or NF-κB activity; however, the same dose of candesartan was previously shown to reduce LPS-induced cytokine expression in numerous brain structure (Benicky et al., 2011). Never-the-less, it remains unclear whether pro-inflammatory cytokines, NF-κB activity, or other mechanisms are responsible for the impaired fear extinction induced by LPS.

Although freezing behavior in rats is not a perfect model of PTSD, our study raises the possibility that a pro-inflammatory state after a traumatic event could contribute to the impaired fear extinction observed in patients with PTSD (Milad et al., 2009). Future studies should elucidate the molecular mechanisms through which inflammatory changes affect extinction learning and memory. Our results suggest that the inflammatory status of the patient may affect the efficacy of integrative treatments that include behavioral interventions such as exposure therapy. These results provide direction for clinical studies of novel treatments that modulate the immune system for stress-related disorders, such as PTSD.

We examined the effects of innate immune activation with lipopolysaccharide on fear extinction.

Activation of the innate immune system impaired auditory fear extinction in adolescent and adult animals.

A sub-chronic treatment with candesartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, prevented the LPS-induced impairment of extinction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMHHD G12MD007579-27 and R15 MH101700 to JTP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adcock IM, Ito K, Barnes PJ. Glucocorticoids: effects on gene transcription. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:247–54. doi: 10.1513/pats.200402-001MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Unal CT, Paré D. Synaptic correlates of fear extinction in the amygdala. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:489–94. doi: 10.1038/nn.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews Ja, Neises KD. Cells, biomarkers, and post-traumatic stress disorder: evidence for peripheral involvement in a central disease. J Neurochem. 2012;120:26–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnis GM, Kohn SR, Henderson M, Brown NL. SSRIs versus non-SSRIs in post-traumatic stress disorder: an update with recommendations. Drugs. 2004;64:383–404. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benicky J, Sánchez-Lemus E, Honda M, Pang T, Orecna M, Wang J, Leng Y, Chuang DM, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade ameliorates brain inflammation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:857–70. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierer LM, Tischler L, Labinsky E, Cahill S, Foa E, Yehuda R. Clinical correlates of 24-h cortisol and norepinephrine excretion among subjects seeking treatment following the world trade center attacks on 9/11. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:514–20. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DY, Lee JW, Lin G, Lee YK, Lee YH, Choi IS, Han SB, Jung JK, Kim YH, Kim KH, Oh KW, Hong JT, Lee MS. Obovatol attenuates LPS-induced memory impairments in mice via inhibition of NF-κB signaling pathway. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H, Kozlovsky N, Matar MA, Zohar J, Kaplan Z. The characteristic long-term upregulation of hippocampal NF-κB complex in PTSD-like behavioral stress response is normalized by high-dose corticosterone and pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate administered immediately after exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2286–302. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C, Sanderson DJ. Malaise in the water maze: untangling the effects of LPS and IL-1beta on learning and memory. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:1117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet CS, Vermetten E, Geuze E, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ, Westenberg HGM. Assessment of HPA-axis function in posttraumatic stress disorder: pharmacological and non-pharmacological challenge tests, a review. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:550–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujihara M, Muroi M, Tanamoto K, Suzuki T, Azuma H, Ikeda H. Molecular mechanisms of macrophage activation and deactivation by lipopolysaccharide: roles of the receptor complex. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;100:171–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill J, Vythilingam M, Page GG. Low cortisol, high DHEA, and high levels of stimulated TNF-alpha, and IL-6 in women with PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:530–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.20372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godsil BP, Kiss JP, Spedding M, Jay TM. The hippocampal-prefrontal pathway: the weak link in psychiatric disorders? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1165–81. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gola H, Engler H, Sommershof A, Adenauer H, Kolassa S, Schedlowski M, Groettrup M, Elbert T, Kolassa IT. Posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with an enhanced spontaneous production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez P, Machado I, Vilcaes A, Caruso C, Roth GA, Schiöth H, Lasaga M, Scimonelli T. Molecular mechanisms involved in interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β)-induced memory impairment. Modulation by alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) Brain Behav Immun. 2013;34:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Liu T, Guo JC, Jiang XL, Chen F, Gao YS. Study on serum cytokine levels in posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5:323–5. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haba R, Shintani N, Onaka Y, Wang H, Takenaga R, Hayata A, Baba A, Hashimoto H. Lipopolysaccharide affects exploratory behaviors toward novel objects by impairing cognition and/or motivation in mice: Possible role of activation of the central amygdala. Behav Brain Res. 2012;228:423–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovljević M, Brajković L, Lončar M, Cima A. Posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD) between fallacy and facts: what we know and what we don’t know? Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24:241–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KA, Thomsen C. The role of the innate immune system in psychiatric disorders. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2013;53:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury NM, Marvar PJ, Gillespie CF, Wingo A, Schwartz A, Bradley B, Kramer M, Ressler KJ. The renin-angiotensin pathway in posttraumatic stress disorder: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are associated with fewer traumatic stress symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:849–55. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranjac D, McLinden KA, Deodati LE, Papini MR, Chumley MJ, Boehm GW. Peripheral bacterial endotoxin administration triggers both memory consolidation and reconsolidation deficits in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:109–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz TW, Klein U. Next generation multifunctional angiotensin receptor blockers. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:826–34. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE, Iwata J, Cicchetti P, Reis DJ. Different projections of the central amygdaloid nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2517–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02517.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist D, Wolkowitz OM, Mellon S, Yehuda R, Flory JD, Henn-Haase C, Bierer LM, Abu-Amara D, Coy M, Neylan TC, Makotkine I, Reus VI, Yan X, Taylor NM, Marmar CR, Dhabhar FS. Proinflammatory milieu in combat-related PTSD is independent of depression and early life stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;42:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvar PJ, Goodman J, Fuchs S, Choi DC, Banerjee S, Ressler KJ. Angiotensin type 1 receptor inhibition enhances the extinction of fear memory. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:864–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum J, Kim JH, Richardson R. Impaired extinction retention in adolescent rats: effects of D-cycloserine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2134–42. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally GP, Johansen JP, Blair HT. Placing prediction into the fear circuit. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:283–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Pitman RK, Ellis CB, Gold AL, Shin LM, Lasko NB, Zeidan MA, Handwerger K, Orr SP, Rauch SL. Neurobiological basis of failure to recall extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:1075–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Fear extinction as a model for translational neuroscience: ten years of progress. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:129–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min LJ, Mogi M, Shudou M, Jing F, Tsukuda K, Ohshima K, Iwanami J, Horiuchi M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation with angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade is pivotal for the prevention of blood-brain barrier impairment and cognitive decline in type 2 diabetic mice. Hypertension. 2012;59:1079–88. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.192401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi M, Miyano K, Moriyama N, Taniguchi M, Watanabe T. Angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonist inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced stimulation of rat microglial cells by suppressing nuclear factor kappaB and activator protein-1 activation. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:343–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.06014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y, Ito T, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II AT(1) blockade normalizes cerebrovascular autoregulation and reduces cerebral ischemia in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke. 2000;31:2478–86. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini CA, Maren S. Neural and cellular mechanisms of fear and extinction memory formation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1773–802. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattwell SS, Duhoux S, Hartley CA, Johnson DC, Jing D, Elliott MD, Ruberry EJ, Powers A, Mehta N, Yang RR. Altered fear learning across development in both mouse and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:16318–16323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206834109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MI, Kagiyama S. Angiotensin II as a pro-inflammatory mediator. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:569–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prager G, Hadamitzky M, Engler A, Doenlen R, Wirth T, Pacheco-López G, Krügel U, Schedlowski M, Engler H. Amygdaloid signature of peripheral immune activation by bacterial lipopolysaccharide or staphylococcal enterotoxin B. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:42–50. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh CR, Kumagawa K, Fleshner M, Watkins LR, Maier SF, Rudy JW. Selective effects of peripheral lipopolysaccharide administration on contextual and auditory-cue fear conditioning. Brain Behav Immun. 1998;12:212–29. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Mueller D. Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:56–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohleder N, Joksimovic L, Wolf JM, Kirschbaum C. Hypocortisolism and increased glucocorticoid sensitivity of pro-Inflammatory cytokine production in Bosnian war refugees with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:745–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CS, Greenbaum MA, Schnurr PP, Holmes TH, Brennan PL, Friedman MJ. Do benzodiazepines reduce the effectiveness of exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:1241–8. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Lemus E, Benicky J, Pavel J, Saavedra JM. In vivo Angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade selectively inhibits LPS-induced innate immune response and ACTH release in rat pituitary gland. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:945–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoia C, Schiffrin EL. Vascular inflammation in hypertension and diabetes: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112:375–84. doi: 10.1042/CS20060247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelling G, Roozendaal B, Krauseneck T, Schmoelz M, DE Quervain D, Briegel J. Efficacy of hydrocortisone in preventing posttraumatic stress disorder following critical illness and major surgery. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:46–53. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp M, Janke J, Clasen R, Unger T, Kintscher U. Angiotensin type 1 receptor blockers induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activity. Circulation. 2004;109:2054–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127955.36250.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Mercado D, Padilla-Coreano N, Quirk GJ. Dissociable roles of prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, ventral hippocampus, and basolateral amygdala in the expression and extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:529–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukuda K, Mogi M, Iwanami J, Min LJ, Sakata A, Jing F, Iwai M, Horiuchi M. Cognitive deficit in amyloid-beta-injected mice was improved by pretreatment with a low dose of telmisartan partly because of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation. Hypertension. 2009;54:782–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.136879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zuiden M, Geuze E, Willemen HLDM, Vermetten E, Maas M, Amarouchi K, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ. Glucocorticoid receptor pathway components predict posttraumatic stress disorder symptom development: a prospective study. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CW, Chen YC, Yu L, Chen H, Jen CJ, Huang AM, Tsai HJ, Chang YT, Kuo YM. Treadmill exercise counteracts the suppressive effects of peripheral lipopolysaccharide on hippocampal neurogenesis and learning and memory. J Neurochem. 2007;103:2471–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Hong T, Shen J, Ding J, Dai XW, Zhou ZQ, Yang JJ. Ketamine exerts antidepressant effects and reduces IL-1β and IL-6 levels in rat prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Exp Ther Med. 2013;5:1093–1096. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Golier JA, Kaufman S. Circadian rhythm of salivary cortisol in Holocaust survivors with and without PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:998–1000. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P, Li Z, Wang YY, Qiao NN, Huang SY, Sun RP, Wang JW. Neonatal immune challenge exacerbates seizure-induced hippocampus-dependent memory impairment in adult rats. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]