Abstract

We demonstrated a novel process to reconstitute a decellularized extracellular matrix (Recon-ECM) of heart and liver tissue using a combination of mechanical homogenization and enzymatic digestion. Such Recon-ECM was used as a biomaterial to produce flat or micro-patterned 2D films after crosslinking using replica molding. The mechanical properties of the resulting films were tuned by changing the type of crosslinking reagents. We also demonstrated the fabrication of mechanically robust 3D scaffolds by freeze-drying of the Recon-ECM solution. The porosity of the 3D scaffold was controlled by changing the concentration of the Recon-ECM. HepG2 cells were used to investigate the potential substrate of these engineered 2D patterned and 3D porous structures. The cell attachment, proliferation, and urea synthesis were evaluated, and the results indicate that the scaffold generated from Recon-ECM provides a biologically friendly environment for cells to grow. This method provides a new way to use decellularized ECM as source of biomaterial to produce novel scaffold with better controlled micro- and nano-scale structures, tunable physicochemical properties with desired biological functions.

Keywords: Decellularized ECM, Reconstitution, 3D tissue scaffold, Micropattening, Lyophilization

INTRODUCTION

Scaffolds made of biomaterials are essential for tissue engineering, as they not only provide a three-dimensional (3D) space for cells to attach and subsequently develop into tissue, but they also encourage vital cellular functions, such as gene expression and matrix production.1, 2 Naturally derived scaffolds made from extracellular matrices (ECM) provide an instructive environment for host cells because of a combination of factors, including tissue-specific structural and functional proteins and growth factors.3 Various decellularized tissues have been shown to generate functional tissues in vitro and in vivo when organ-specific cells are cultured inside them.4–13 Animal studies have shown that ECM is transplantable and improves the tissue functions of several tissues including the liver and heart.6, 7 However, perfusion is required to seed cells in decellularized whole tissue scaffolds. In addition, it is difficult to regenerate a complex, hierarchical organ structure, in which many types of cells are organized into specialized tissues, from a whole decellularized organ because the cells are seeded through the veins.5

Processing of decellularized tissue ECM has previously been explored. Lin et al. decellularized thick liver tissue slices for tissue engineering applications as an alternative to conventional 3D double gel culture.8 Several groups have demonstrated that decellularized tissue ECM can be solubilized and used to coat tissue culture plates.9, 10 Other groups produced injectable gels derived from myocardial, urinary bladder, and liver ECM.11–13 However, in previous studies the decellularized ECM had not been manipulated into micropatterned films and porous scaffolds, which could be used for many biomedical applications. Here, we present a method to create 2D films and 3D scaffolds with controlled properties using reconstituted decellularized ECM (Recon-ECM).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Recon-ECM

We used a previously published procedure to produce a decellularized ECM.10 Briefly, bovine liver or heart tissues (from a local butcher shop) were cut into small pieces of < 1 cm3 in volume using a razor blade, and then thoroughly rinsed in deionized (DI) water for 30 min to remove any blood and cellular debris. The pieces were transferred into a phosphate buffer saline (PBS, Boston BioProducts, Ashland, MA) solution containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 1% penicillin streptomycin (Pen Strep, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) to remove the cellular components for 3–5 days for their complete decellularization. The decellularization solution was changed daily. The decellularized tissues were then rinsed in DI water overnight to remove SDS. The pieces were then mechanically broken down into fine ECM fibers with a blender (Black & Decker, New Britain, CT) and a homogenizer (IKA, Staufen, Germany). The resulting samples can either be lyophilized and stored at −20°C for future use, or further broken down into a gel-like material using enzyme digestion for 2 days. The enzyme solution used for digestion contains 2 mg/mL pepsin (≥ 2500 unit/mg, Sigma-Aldrich) solution (pH = 1) containing 0.1 M hydrochloric acid (VWR, Radnor, PA).

Fabrication of 2D films from Recon-ECM

In order to fabricate flat films, we cast the Recon-ECM premixed with crosslinker into a paraffin mold on a flat glass substrate and the samples air-dried overnight. The paraffin mold (Fig. 2A) was created as follows: Glass microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) were covered with molten paraffin (Fisher Scientific), and then the paraffin was solidified by cooling at room temperature. Paraffin was removed to form a mold by using a razor blade. Different crosslinkers including: transglutaminase (TG) (Activa TI, Ajinomoto Food Ingredients, Vernon Hills, IL), 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Co. Ltd., Portland, OR), or glutaraldehyde (GA) (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) were used. The concentration of the Recon-ECM solution was 2% (w/v) and the concentration of the crosslinkers was 1%. Micropatterned 2D films were created by covering the cross-linked ECM solution with a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) micromold and letting it dry overnight. PDMS micromolds were prepared using standard soft lithography.14

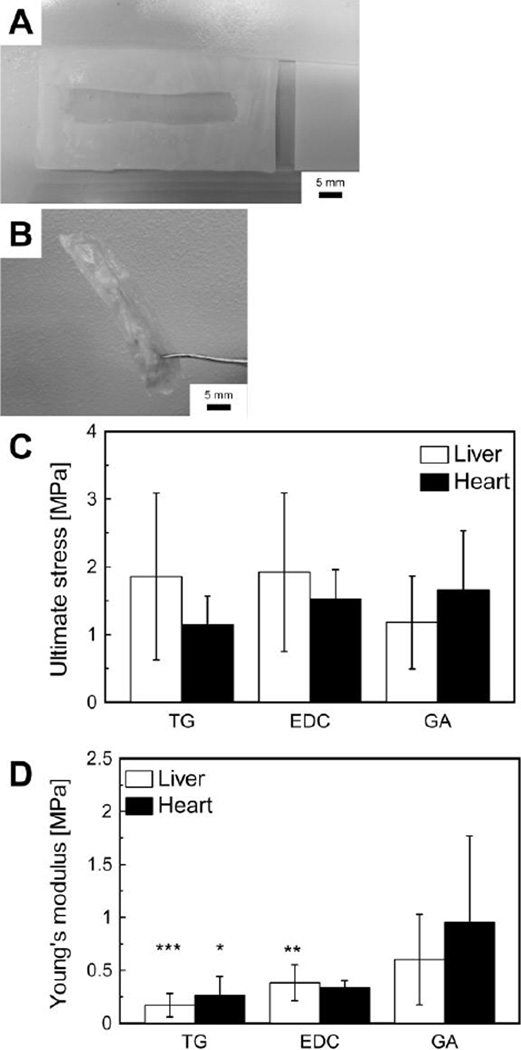

Fig. 2.

Mechanical properties of Recon-ECM films with different crosslinking agents. (A) Paraffin mold used to create Recon-ECM films. (B) Photo of a resulting Recon-ECM film. (C) Ultimate stress of liver and heart Recon-ECM film samples. (C) Young’s modulus of liver and heart Recon-ECM films. Three crosslinkers were tested: TG, transglutaminase; EDC, 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride; GA, glutaraldehyde. *: p > 0.05, **: p > 0.01, ***: p > 0.001, comparing with GA. Sample size n = 7 or 8. All error bars represent standard deviation.

Mechanical testing

Mechanical testing of the samples was conducted in a tensile setup using a mechanical testing machine (Instron, Norwood, MA) with a 250 N load cell. The Recon-ECM film samples of a rectangular shape were used in a dry state. Testing was conducted at a strain rate of 0.3%/s until failure. The Young’s modulus was defined as the slope of a linear fit to the stress–strain curve.

Fabrication of 3D porous scaffolds

Lyophilization was used to create 3D porous Recon-ECM scaffolds. The pepsin-digested Recon-ECM solution was mixed with various crosslinkers (ECM concentration: 0.5%, 1%, and 2% w/v) and poured into molds. The ratio of the crosslinker to ECM was 1:2 (crosslinker: ECM in weight). After 1 h of crosslinking, the ECM was frozen at −80°C overnight, and then the water component was removed using a lyophilizer (Labconco, Kansas City, MO). The removal of the water components creates porous 3D scaffolds.

3D scaffolds with microchannels were created using a linear wire array (diameter of wires, 250 µm). The linear wire array was prepared as described previously by Wray et al.15 Recon-ECM solution premixed with TG was poured into a mold containing a linear wire array, frozen, and then lyophilized. After drying, the wire array template was removed from the scaffold.

PLGA control scaffolds were prepared by salt leaching.16, 17 Briefly, 2 g of 75:25 poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 2 mL of dichloromethane (Avantor Performance Materials, Center Valley, PA). Two grams of sodium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) was then added to the PLGA solution and the mixture left to dry for 2 days. Once dry the resulting scaffolds were immersed in DI water for 2 days to leach out the sodium chloride. The salt-free scaffolds were then air-dried for 24 h.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The surface structures of Recon-ECM films and scaffolds were observed with SEM (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Film samples were dehydrated by immersing them serially in 50% ethanol (Electron Microscopy Sciences), 70% ethanol, 95% ethanol, and 100% ethanol twice for 2 min each. The samples were then completely dried by incubation in hexamethyldisilazane (Sigma-Aldrich). Lyophilized 3D samples used for SEM had the surfaces of the samples trimmed in order to observe the porous structure inside the scaffolds. The samples were coated with a thin layer of gold using a sputter coater (Quorum Technologies Ltd., West Sussex, UK).

Cell culture

HepG2 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 100 units /mL Pen Strep at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. HepG2 cells were removed from a culture flask (Fisher Scientific) by adding 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) to the culture medium and were seeded on the samples.

HepG2 cells were seeded on a micropatterned Recon-ECM film (5 × 104 cells/sample). A PDMS weight, which has a hole (6 mm in diameter), was placed to prevent the Recon-ECM film from floating in the medium. Soon after seeding, the cells were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 2 min so that the cells could attach to the bottom of the micropatterns. After 24 h of culture, the HepG2 cells were fixed with 10% buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific) for 5 min, and phase contrast images of the cells were taken under a microscope (Leica, Solms, Germany).

Before seeding HepG2 cells on the 3D Recon-ECM scaffolds, the surfaces of the scaffolds were trimmed. The samples were cut into disc shape (6 mm in diameter and 2 mm in height). All samples were sterilized with UV light and 70% ethanol. The scaffolds were extensively washed with PBS and then immersed in DMEM. HepG2 cells were seeded in the scaffolds with the seeding density of 2 × 105 cells per scaffold. The cells were cultured in scaffolds at 37°C for 3, 5, and 7 days.

Cell staining and imaging

The cell growth in the 3D scaffolds was observed using a confocal microscope after 7 days of culture following a modified protocol of Gantenbein-Ritter et al.18 Briefly, the samples were immersed in 2 µM calcein AM (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) in PBS and incubated for 90 min at 37°C. The stained sample was then observed using a DM IRE2 (Leica).

Cell viability assay

The number of cells in the scaffolds was analyzed using MTT assay. At each time point (3, 5, and 7 days after seeding), 0.5 mg/mL thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich) in DMEM was added to each sample and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. After that, the MTT solution was removed and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to dissolve the converted dye. The absorbance at 560 nm was quantified with a plate reader (Molecular Devices, CA).

Urea synthesis

Urea synthesis was measured by the diacetyl monoxime (DAM) method, following the protocol of Wybenga et al.19 Briefly, media samples were collected daily and stored at 4°C before use. Each sample (40 µL) was added to 5 mL of urea nitrogen reagent, which contains 0.825 M sulfuric acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 1.08 M phosphoric acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.549 mM thiosemicarbazide (Sigma-Aldrich), and 6.31 mM cadmium sulfate hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich). Then, 500 µL of 2% 2,3-butanedione monoxime (Sigma-Aldrich) solution was added to the sample, and the sample was mixed by inversion. The samples were placed in a 100°C heating block to commence the reaction. The absorbance at 540 nm was read using a plate reader.

Statistic analysis

Statistical differences in the mechanical properties and cell viability were assessed using one-way analysis of valiance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post-hoc test. All statistical tests were two-tailed analyses, with significance set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

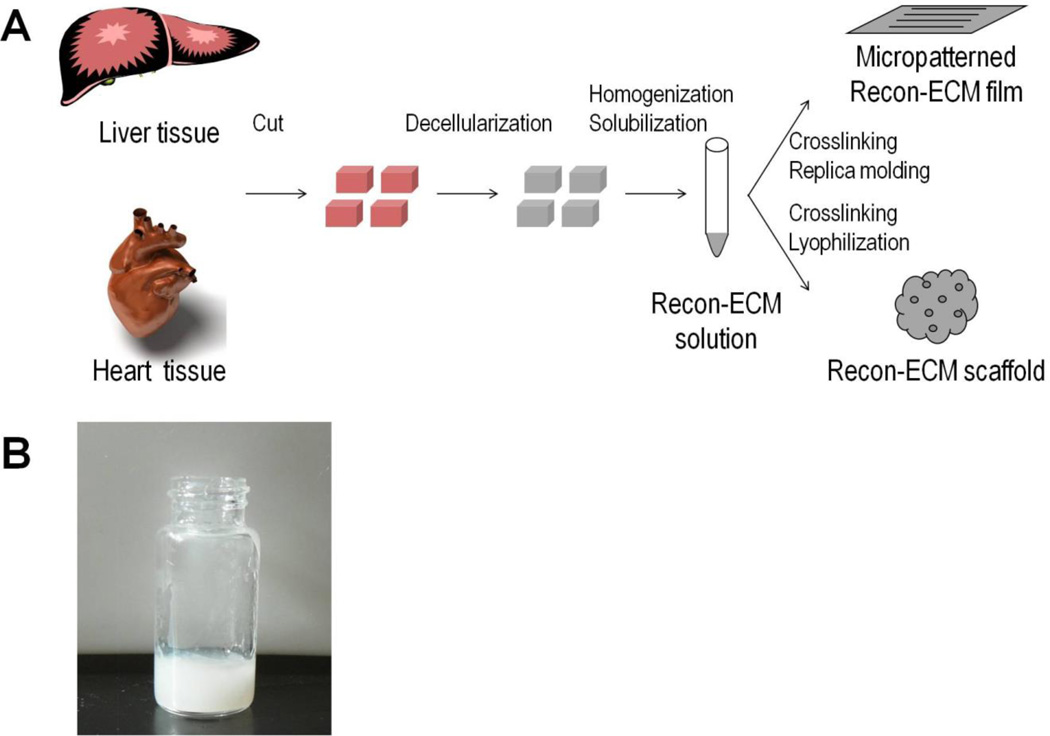

Figure 1A shows the process to generate Recon-ECM from biological tissues and the fabrication of 2D and 3D constructs from Recon-ECM. Liver and heart tissues were decellularized and then mechanically broken down into fine ECM fibers that could be further broken into gels by pepsin digestion (Fig. 1B). Such Recon-ECM gels could be used as a source of biomaterials, similar to commonly used biomaterials like collagen or silk fibroin gel, to generate 2D films and 3D scaffolds.

Fig. 1.

(A) Scheme of processing tissues into Recon-ECM films and scaffolds. (B) Recon-ECM gel after mechanical and enzymatic digestion.

We generated thin films by casting the Recon-ECM gel into a paraffin mold on a flat glass substrate. However, these films easily fell apart when soaked in aqueous solution. The integrity of the resulting films was retained in aqueous solution by premixing the Recon-ECM solution with various crosslinkers (Fig. 2B). We used three types of crosslinkers: transglutaminase (TG), 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), and glutaraldehyde (GA). Figure 2 shows the mechanical properties of the 2D films generated from liver and heart Recon-ECM after crosslinking. There was no significant difference in ultimate stress (Fig. 2C). The Young’s modulus of Recon-ECM films cross-linked with GA was significantly higher than that of the samples crosslinked with either TG or EDC (Fig. 2D). The Young’s moduli of Recon-ECM films were higher than those of EDC-crosslinked collagen gels and decellularized whole liver tissues (0.1 MPa),20, 21 while the values were lower than those of collagen film (2.32 ± 1.24 MPa).22 The mechanical properties of the Recon-ECM generated from liver and heart were in a similar range. These results might be attributed to the process of breaking down the ECM components by either mechanical break down or the pepsin digestion.

Transglutaminase (TG) is an enzyme-based crosslinker for proteins and peptides. TG is biocompatible and has been studied for several tissue engineering applications,23, 24 while GA and EDC could affect cell growth or cause cell death.20 In the following study, we only used TG as a crosslinker for creating scaffolds.

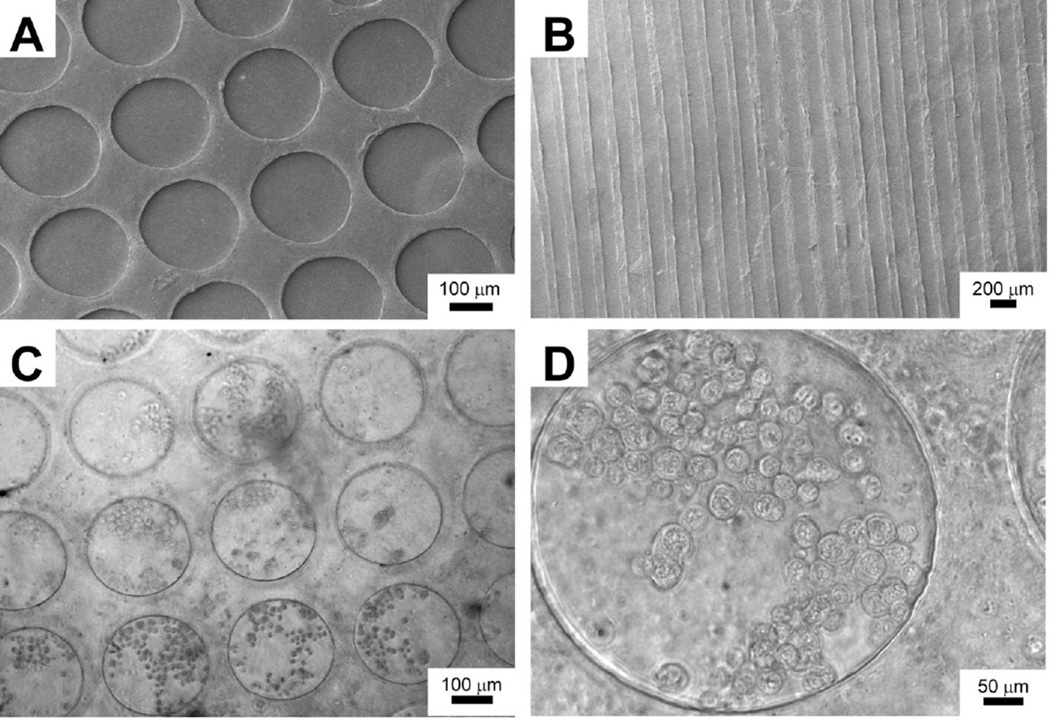

We created Recon-ECM films with micropatterns by casting the Recon-ECM mixed with TG against a patterned PDMS substrate. After air-drying over night, the Recon-ECM films were mechanically robust and could be peeled off from PDMS templates using a pair of forceps. Figures 3A and B show SEM images of the micropatterned surfaces from liver Recon-ECM. In order to evaluate whether the Recon-ECM is a suitable substrate for cell growth, we studied cell attachment on the liver Recon-ECM substrate within microwells. HepG2 cells easily attached to the surface of the Recon-ECM films, as shown in Figs. 3C and D. The patterned microstructures of the liver Recon-ECM films were stable during the cell culture. No obvious cytotoxicity caused by the crosslinked Recon-ECM was observed. Topographic features on biomaterials have been shown to affect cell behavior, such as morphology, orientation, and migration.25, 26 These microwells could be used to promote spheroid formation of hepatic cells and to coculture liver cells with fibroblasts to enhance hepatic function.27–29 The Recon-ECM enables us to produce the substrate with pre-designed patterns, which may provide physiologically relevant cell-culture conditions.

Fig. 3.

(A, B) SEM images of liver Recon-ECM films with micropatterns. (C, D) Phase contrast images of HepG2 cells seeded on liver Recon-ECM films with micropatterns (24 h after seeding).

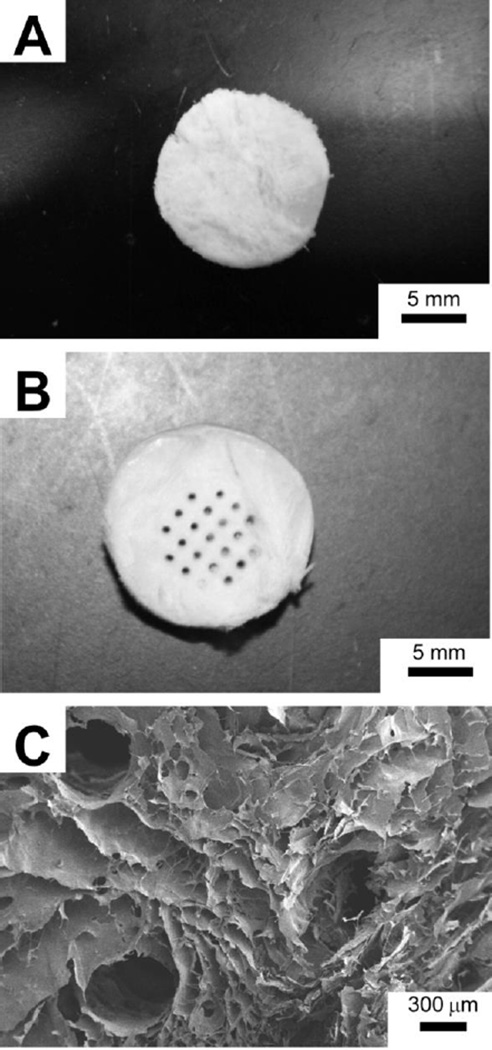

In addition to 2D films, we also demonstrated the application of Recon-ECM to generate 3D porous scaffold by freeze-drying. Figure 4A is a photograph of the resulting 3D scaffold from liver Recon-ECM. Incorporation of macroscale channels into the porous scaffold could facilitate nutrient and waste exchange to provide a better environment for cell growth. Using a technique recently developed by Wray et al.,15 we produced a porous 3D scaffold containing an array of hollow channels. Figure 4B shows the photograph of the resulting 3D scaffold. The large hollow channels (diameter: 300–500 µm) in the porous scaffold were visualized using SEM (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

(A) 3D porous liver Recon-ECM scaffold after lyophilization. (B) Heart Recon-ECM scaffolds with micro-scale channels created with a linear wire array and (C) its SEM image.

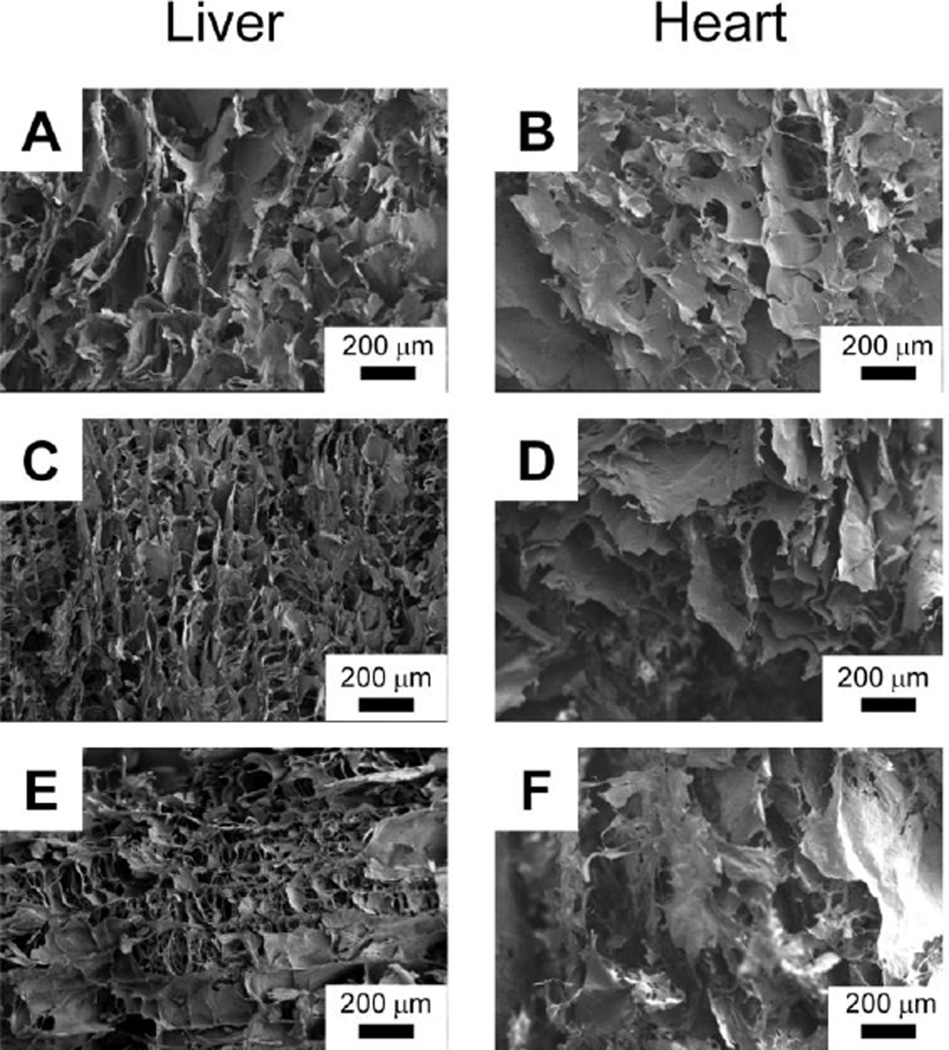

The porosity of the 3D scaffold from Recon-ECM could be easily controlled by varying the concentration of the Recon-ECM solution. Figure 5 shows the morphology of the cross-section of scaffolds made from liver and heart Recon-ECM with different concentrations. Larger pores in the resulting scaffolds were observed at higher concentrations of Recon-ECM. During the freeze-drying process, the Recon-ECM generally formed flake-like microstructures, while the fibrous structure was also observed at low concentrations of Recon-ECM (Fig. 5E). The flake-like structure was more apparent in heart Recon-ECM scaffolds than in liver Recon-ECM scaffolds. Although the difference in appearance might be attributed to the different composition of the native ECM between liver and heart, the exact reason remains to be studied.

Fig. 5.

SEM images of liver and heart Recon-ECM scaffolds with different ECM concentration (A and B, 2%; C and D, 1%; E and F, 0.5%). All samples were crosslinked with transglutaminase (TG).

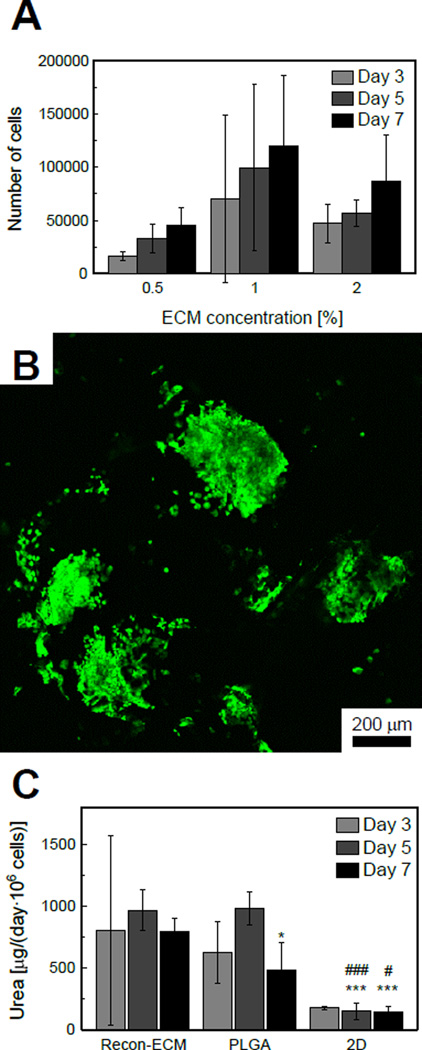

To test whether the 3D Recon-ECM scaffolds are useful for cell growth, HepG2 cells were cultured in 3D liver Recon-ECM scaffolds for up to 7 days. The cell proliferation in the scaffold was quantified with MTT assay (Fig. 6A). HepG2 cells tended to proliferate with time in liver Recon-ECM scaffolds with all ECM concentrations, although the increase was not statistically significant. The number of cells in 1% ECM samples tended to be higher than those in 0.5% and 2% samples, although the difference was not statistically significant. In order to check whether the cells penetrate into the inner surface of the scaffold, we labeled live cells with calcein AM and imaged using confocal microscopy. As we can see from Fig. 6B, after 7 days of culture, the cells attached to inner surface of the scaffold and retained the ability to proliferate. In order to characterize the liver-specific function of HepG2 cells in Recon-ECM scaffolds, urea synthesis, a marker of nitrogen metabolism, was quantified. The cells were cultured in Recon-ECM (ECM concentration, 1%) and PLGA scaffolds and tissue culture plates. The amount of urea on day 7 standardized by the number of cells was significantly higher in Recon-ECM than in PLGA scaffolds and 2D culture (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

(A) Proliferation of HepG2 cells in Recon-ECM scaffolds with different ECM concentration, quantified by MTT assay. Sample size n = 3. (B) A confocal image of HepG2 cells in a liver Recon-ECM scaffold (ECM concentration, 1%) after 7 days of culture. (C) Amount of urea secreted in a day, standardized by the number of cells. *: p > 0.05, ***: p > 0.001, comparing with Recon-ECM. #: p > 0.05, ###: p > 0.001, comparing with PLGA. Sample size n = 4. All error bars represent standard deviation.

Porous structures have been known to help tissue regeneration and the transport of nutrients and metabolic wastes.1, 30 The lower the ECM concentration was, the smaller pores in the resulting scaffolds we observed. Tierney et al. pointed out that the higher collagen concentration facilitates the nucleation of ice crystals, which then increases the pore size of collagen-GAG scaffolds created with lyophilization.31 The number of HepG2 cells in the scaffolds, characterized by MTT assay, was higher in 1% and 2% liver Recon-ECM scaffolds than in 0.5% Recon-ECM scaffolds at all time points. This result may be attributed to the higher permeability of the 1% and 2% ECM scaffolds, which is proportional to the square of the diameter of pores, permitting more cells to penetrate into and attach to the scaffolds.31, 32 A scaffold generated from 1% liver Recon-ECM showed better cell growth than that generated from the 2% one. This result may be attributed to the larger surface area per volume (specific surface area) of 1% Recon-ECM scaffolds, which is inversely proportional to the pore diameter, producing a higher ligand density for cells to attach to.33 The urea synthesis in Recon-ECM scaffolds was better than in PLGA. The functional proteins in the Recon-ECM scaffolds could promote the tissue growth and upregulate the cell functions. It has been reported that the porous structure created by lyophilization can be designed by changing parameters such as ECM concentration, crosslinking conditions, freezing temperature, and annealing.31, 34 Optimization of these parameters could provide better porosity of Recon-ECM scaffolds to further promote initial cell attachment and subsequent tissue formation.

CONCLUSION

In this study we have demonstrated the process of generating reconstituted ECM (Recon-ECM) from decellularized biological tissues, such as heart and liver. Recon-ECM can be considered a new type of biological material, similar to reconstituted collagen, which is widely used for many biomedical applications. We have created 2D films by replica molding and 3D scaffolds using freeze-drying and evaluated their structural integrity following crosslinking through various methods. Additionally we showed that cells could easily attach to and proliferate on the 2D and 3D constructs generated from Recon-ECM. The adult biological tissues used in this method, such as swine or bovine liver and heart, are readily available, making this an inexpensive but valuable source of biomaterials, considering the decellularized ECM comprises various tissue-specific proteins and growth factors.13, 35 Recon-ECM can be an alternative to widely used biomaterials in tissue engineering (e.g. PLGA, polystyrene, collagen, and silk).

Acknowledgements

QX acknowledges the support from NIH (R03 EB 017402) and Pew Scholar for Biomedical Sciences program from Pew Charitable Trusts. The authors thank Tahmid Lahman for helping prepare the ECM films and Nicholas Bayhi and Kyle A. Alberti for proofreading the manuscript. The authors also would like to thank Lindsay S. Wray and Dr. Jelena Rnjak-Kovacina for kindly providing the linear wire array.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hutmacher DW. Scaffold design and fabrication technologies for engineering tissues--state of the art and future perspectives. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2001;12:107–124. doi: 10.1163/156856201744489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owen SC, Shoichet MS. Design of three-dimensional biomimetic scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;94:1321–1331. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badylak SF. The extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s1084952102000940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert TW, Sellaro TL, Badylak SF. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3675–3683. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirakigawa N, Ijima H, Takei T. Decellularized liver as a practical scaffold with a vascular network template for liver tissue engineering. J Biosci Bioeng. 2012;114:546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uygun BE, Soto-Gutierrez A, Yagi H, Izamis ML, Guzzardi MA, Shulman C, Milwid J, Kobayashi N, Tilles A, Berthiaume F, Hertl M, Nahmias Y, Yarmush ML, Uygun K. Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularized liver graft using decellularized liver matrix. Nat Med. 2010;16:814–820. doi: 10.1038/nm.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh SK, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, Taylor DA. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:213–221. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin P, Chan WCW, Badylak SF, Bhatia SN. Assessing porcine liver-derived biomatrix for hepatic tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1046–1053. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, He Y, Bharadwaj S, Hammam N, Carnagey K, Myers R, Atala A, Van Dyke M. Tissue-specific extracellular matrix coatings for the promotion of cell proliferation and maintenance of cell phenotype. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4021–4028. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeQuach JA, Mezzano V, Miglani A, Lange S, Keller GM, Sheikh F, Christman KL. Simple and high yielding method for preparing tissue specific extracellular matrix coatings for cell culture. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freytes DO, Martin J, Velankar SS, Lee AS, Badylak SF. Preparation and rheological characterization of a gel form of the porcine urinary bladder matrix. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1630–1637. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singelyn JM, DeQuach JA, Seif-Naraghi SB, Littlefield RB, Schup-Magoffin PJ, Christman KL. Naturally derived myocardial matrix as an injectable scaffold for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5409–5416. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sellaro TL, Ranade A, Faulk DM, McCabe GP, Dorko K, Badylak SF, Strom SC. Maintenance of human hepatocyte function in vitro by liver-derived extracellular matrix gels. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1075–1082. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khademhosseini A, Langer R, Borenstein J, Vacanti JP. Microscale technologies for tissue engineering and biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2480–2487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507681102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wray LS, Rnjak-Kovacina J, Mandal BB, Schmidt DF, Gil ES, Kaplan DL. A silk-based scaffold platform with tunable architecture for engineering critically-sized tissue constructs. Biomaterials. 2012;33:9214–9224. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon JJ, Kim JH, Park TG. Dexamethasone-releasing biodegradable polymer scaffolds fabricated by a gas-foaming/salt-leaching method. Biomaterials. 2003;24:2323–2329. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikos AG, Sarakinos G, Leite SM, Vacanti JP, Langer R. Laminated three-dimensional biodegradable foams for use in tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 1993;14:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(93)90049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gantenbein-Ritter B, Sprecher CM, Chan S, Illien-Junger S, Grad S. Confocal imaging protocols for live/dead staining in three-dimensional carriers. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;740:127–140. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-108-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wybenga DR, Di Giorgio J, Pileggi VJ. Manual and automated methods for urea nitrogen measurement in whole serum. Clin Chem. 1971;17:891–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duan X, Sheardown H. Dendrimer crosslinked collagen as a corneal tissue engineering scaffold: mechanical properties and corneal epithelial cell interactions. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4608–4617. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kajbafzadeh AM, Javan-Farazmand N, Monajemzadeh M, Baghayee A. Determining the Optimal Decellularization and Sterilization Protocol for Preparing a Tissue Scaffold of a Human-Sized Liver Tissue. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2013 doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2012.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pins GD, Christiansen DL, Patel R, Silver FH. Self-assembly of collagen fibers. Influence of fibrillar alignment and decorin on mechanical properties. Biophys J. 1997;73:2164–2172. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78247-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorand L, Graham RM. Transglutaminases: crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrm1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orban JM, Wilson LB, Kofroth JA, El-Kurdi MS, Maul TM, Vorp DA. Crosslinking of collagen gels by transglutaminase. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2004;68A:756–762. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis A, Wilkinson C. Topographical control of cells. Biomaterials. 1997;18:1573–1583. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai X, Xu Q. Nanostructured substrate fabricated by sectioning tendon using a microtome for tissue engineering. Nanotechnology. 2011;22:494008. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/49/494008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tagaya M, Yamazaki T, Tsuya D, Sugimoto Y, Hanagata N, Ikoma T. Nano/microstructural effect of hydroxyapatite nanocrystals on hepatocyte cell aggregation and adhesion. Macromol Biosci. 2011;11:1586–1593. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201100182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura T, Sakai Y, Nakazawa K. Two-dimensional microarray of HepG2 spheroids using collagen/polyethylene glycol micropatterned chip. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19:2071–2077. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khetani SR, Bhatia SN. Microscale culture of human liver cells for drug development. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:120–126. doi: 10.1038/nbt1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen GP, Ushida T, Tateishi T. Scaffold design for tissue engineering. Macromol Biosci. 2002;2:67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tierney CM, Haugh MG, Liedl J, Mulcahy F, Hayes B, O'Brien FJ. The effects of collagen concentration and crosslink density on the biological, structural and mechanical properties of collagen-GAG scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2009;2:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Brien FJ, Harley BA, Waller MA, Yannas IV, Gibson LJ, Prendergast PJ. The effect of pore size on permeability and cell attachment in collagen scaffolds for tissue engineering. Technol Health Care. 2007;15:3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Brien FJ, Harley BA, Yannas IV, Gibson LJ. The effect of pore size on cell adhesion in collagen-GAG scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2005;26:433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haugh MG, Murphy CM, O'Brien FJ. Novel freeze-drying methods to produce a range of collagen-glycosaminoglycan scaffolds with tailored mean pore sizes. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:887–894. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voytik-Harbin SL, Brightman AO, Kraine MR, Waisner B, Badylak SF. Identification of extractable growth factors from small intestinal submucosa. J Cell Biochem. 1997;67:478–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]