Abstract

The efficacy and consequential validity of an ecological approach to behavioral intervention with families of children with developmental disabilities was examined. The approach aimed to transform coercive into constructive parent-child interaction in family routines. Ten families participated, including 10 mothers and fathers and 10 children 3–8 years old with developmental disabilities. Thirty-six family routines were selected (2 to 4 per family). Dependent measures included child problem behavior, routine steps completed, and coercive and constructive parent-child interaction. For each family, a single case, multiple baseline design was employed with three phases: baseline, intervention, and follow-up. Visual analysis evaluated the functional relation between intervention and improvements in child behavior and routine participation. Nonparametric tests across families evaluated the statistical significance of these improvements. Sequential analyses within families and univariate analyses across families examined changes from baseline to intervention in the percentage and odds ratio of coercive and constructive parent-child interaction. Multiple baseline results documented functional or basic effects for 8 of 10 families. Nonparametric tests showed these changes to be significant. Follow-up showed durability at 11 to 24 months postintervention. Sequential analyses documented the transformation of coercive into constructive processes for 9 of 10 families. Univariate analyses across families showed significant improvements in 2- and 4-step coercive and constructive processes but not in odds ratio. Results offer evidence of the efficacy of the approach and consequential validity of the ecological unit of analysis, parent-child interaction in family routines. Future studies should improve efficiency, and outcomes for families experiencing family systems challenges.

Keywords: Positive behavior support, applied behavior analysis, family centered service delivery, behavioral family intervention, parent-child interaction, sequential analysis

Introduction

Problem behaviors are a major source of stress for families raising children with developmental disabilities (Baker, Blacher, Crnic & Edelbrock, 2003), and are associated with significant social costs, including parent health problems, maternal depression, marital strain, and out-of-home placement (Bromley & Blacher, 1991). Consequently, many families of children with developmental disabilities have a significant need for behavior support services. Although models of service delivery have improved (Roberts, Mazzucchelli, Studman, & Sanders, 2006), families continue to report difficulty in obtaining acceptable and effective behavior support services. Families and practitioners report the need for: (a) assessments that are strength-based and help families understand problem behavior; (b) behavior support services that address all of the family contexts in which problem behaviors occur; (c) behavior support procedures that are positive, practical, and culturally-sensitive; and (d) outcomes that are sustainable within the natural contexts of family life (Carr, 2007; Turnbull & Ruef, 1996).

Behavioral scientists (Baer, 1986) speak directly to these consumer needs when they argue that the ultimate criterion for the value of behavioral interventions is their “survivability” in natural settings. For families of children with disabilities, “survivable” interventions are those that remain acceptable, effective, durable, and sustainable across a long period of time, best measured in years after formal behavior support services have been terminated.

Three gaps exist in the literature on intervention with families of children with disabilities. First, there are very few studies of parent-child interaction in family contexts. Consequently, our understanding of the etiology of problem behavior in family life is not well developed. Second, only a small number of empirical analyses have documented the effectiveness of positive behavior interventions used by parents of children with disabilities in family contexts (Buschbacher, Fox, & Clarke, 2004; Dunlap & Fox, 1999; Feldman, Condillac, Tough, Hunt, & Griffiths, 2002; Lucyshyn, Albin, & Nixon, 1997; Lucyshyn et al., 2007). Third, few studies have documented the long-term maintenance of outcomes in family settings.

To promote the design of survivable interventions when implemented by parents in family contexts, Lucyshyn et al. (2009) developed an ecological approach to behavioral intervention with families of children with developmental disabilities and severe problem behavior. The approach, ecological, family centered positive behavior support, is based on an expanded ecological unit of analysis—coercive processes in family routines—that integrates three theories related to child behavior and development in the home: (a) behavioral theory, with its focus on the environmental determinants and functions of child problem and adaptive behavior (Repp & Horner, 1999); (b) coercive family process theory, with its expanded focus on micro-interactional processes of parent-child interaction (Patterson, 1982); and (c) ecocultural theory, with its attention to the activity setting (routine) as an ecological context for child development in the family (Gallimore, 2005). Single case research has offered preliminary evidence of the effectiveness, acceptability, and durability of the approach for improving child behavior and participation in family routines (Buschbacher et al., 2004; Lucyshyn et al., 2007).

Parallel to research on the effectiveness and acceptability of the approach, Lucyshyn et al. (2004) initiated a line of sequential analysis research to develop the construct validity of coercive processes in family routines as an ecological unit of analysis. Following Messick's model of construct validation (Messick, 1988), Lucyshyn et al. conducted an observational study to investigate the construct's evidential validity; that is, the extent to which the construct can be shown to exist. Ten families of children with developmental disabilities and problem behavior participated in videotaped observations in problematic home routines. Sequential analysis results confirmed the presence of two stable coercive processes. In routines in which parents were busy and unable to fully attend to their child (e.g., doing household chores, preparing dinner), four-step attention-driven coercive processes were documented (i.e., parent busy → child problem behavior → parent positive or negative attention → child reduce or terminate problem behavior). In routines in which parent demands were common (e.g., dinner, homework), a variation of the four-step escape-driven coercive process identified by Patterson (1982) was evidenced (e.g., parent demand → child problem behavior → parent reduce demand → child reduce or terminate problem behavior).

This study had two purposes. The first purpose was to strengthen the internal, external, and social validity of the ecological, family centered PBS approach. The key question asked was, “does the approach promote acceptable, durable, and sustainable improvements in child behavior and routine participation?” A second purpose was to investigate the consequential validity of the construct of coercive processes in family routines; that is, the extent to which the ecological unit of analysis promotes survivable interventions in family contexts (Messick, 1988). The key question asked was, “does the ecological unit of analysis promote the transformation of coercive into constructive processes of parent-child interaction in family routines?”

Method

Participants

Twelve families of children with developmental disabilities and severe problem behavior were initially enrolled in the study. Families were recruited through referrals from private agencies, non-profit organizations, and public agencies that provided special education, family support, or advocacy services to families. A telephone-screening interview was conducted with parents, followed by a formal screening process involving brief functional assessment and routine assessment, and direct observations. Children and families who met the following criteria were invited to participate in the study: (a) the child had a diagnosis of a developmental disability (e.g., autism, intellectual disability); (b) the child engaged in severe problem behavior in two or more family routines (i.e., screaming, tantrums, physical aggression, and/or destructive behavior); and (c) both mother and father were willing to serve as interventionists with the child within a longitudinal study.

Participating children (8 boys, 4 girls) were between 4 and 8 years old at the start of the study in 2004 (M = 6.2 years), and between 9 and 16 years old (M = 12.4) at its conclusion in 2008 for two families, 2010 for seven families, and 2012 for one family. Diagnosed developmental disabilities were autism (7 children, with 2 low functioning and 5 high functioning), Asperger Syndrome (1 child), mild intellectual disability and autism (1 child), moderate intellectual disability (1 child), severe developmental delay (1 child), and CHARGE syndrome and moderate intellectual disability (1 child). Eleven of 12 families included both parents living together in the family home; one family included a mother living in Canada while father lived in China. At the start of the study, mothers’ average age was 42.3 years and fathers’ average age was 41.6 years. Ten of 12 families had between one and three typically developing siblings, while one family had an older son with autism and another family had no siblings. Children's problem behavior included non-compliance, leaving assigned area, defiance, food refusal, tantrums, physical aggression, and destructive behavior. The study included six families of European heritage, four families of Asian heritage (Chinese, Taiwanese, and Japanese), one African-American family, and one family of middle-eastern heritage (Iranian). Four families were of lower income, seven families were of middle income, and one family was of upper income. Across 4 to 6 years of assessment and intervention, the retention rate was 83% (10 of 12 families), with two families withdrawing from the study in the second year.

The study was conducted across two sites, with nine families at the main research site in British Columbia (BC) and three families at a consortium site in New Jersey (NJ). Two to four valued but problematic activity settings (i.e., routines) were defined in collaboration with each family (Gallimore, 2005). Across the 10 families who maintained enrolment, a total of 36 routines were selected, including 28 home routines (e.g., getting ready for school, dinner, bedtime) and 8 community routines (e.g., grocery shopping, eating at restaurant).

Procedure

Research and intervention procedures were implemented and coordinated by the PI and Co-I at their respective sites. Two doctoral student interventionists and one master's level interventionist at the BC site implemented the PBS approach with 2 to 3 families each, with the PI serving as co-interventionist with 5 families and providing weekly or bi-weekly supervision. The Co-I and doctoral student interventionist at the NJ site shared responsibility for implementing the approach with two families, with the Co-I providing weekly supervision. A counseling or clinical psychologist at each site provided two hours of clinical supervision, focused on family systems and treatment adherence, on a monthly basis to the intervention teams at their respective sites. The counseling psychologist in BC also provided, across 4 years, 70 hours of counseling support or treatment (i.e., cognitive behavior therapy) for three families.

Preliminary assessment

Preliminary assessment activities were conducted to define problem behavior, identify target routines, and establish a structured baseline across routines.

Design of break procedure

Before initiating the baseline phase with each family, a break procedure was developed in order to reduce parent reactivity. As observed by Lucyshyn et al. (2004) in their study of coercive processes, parents tended to persist with routine related demands while being videotaped and to terminate demands only after the observer ended the observation session. To correct this reactivity, a break procedure was designed to ensure that naturally occurring escape-driven coercive processes would be observed in family routines.

Baseline

During the baseline phase, all dependent variables were measured. Videotaped observations occurred in two to four target routines for each family. Initial baseline measurement continued until a stable or increasing trend in child problem behavior was documented.

Intervention

During the intervention phase, the components of the ecological, family centered PBS approach were implemented. These are described below.

Comprehensive assessment

A functional assessment was completed for each focus child. Interventionists used the Functional Assessment Interview (FAI) form (O'Neill et al., 1997). Functional assessment observations and functional analyses were then conducted to verify hypotheses about the functions of problem behavior. Second, a family ecology assessment was completed. Interventionists used a semi-structured interview to ask parents about child and family goals, family strengths, resources and social supports, and sources of stress.

Positive behavior support plan design

In collaboration with each family, interventionists developed a PBS plan for the child in target routines. PBS plans were designed to be technically sound and contextually appropriate. A competing behaviors analysis framework (O'Neill et al., 1997) was used to select setting event, antecedent, teaching, and consequence strategies that would render problem behavior ineffective at achieving its function. Contextual fit logic (Albin, Lucyshyn, Horner, & Flannery, 1996) guided the design of a plan that was contextually appropriate. Adjunctive family centered supports were offered and provided to address barriers to change that were present within the family system (e.g., mindfulness training for parent with difficulty regulating attention; CBT for parent with anxiety disorder, marital counseling for family experiencing marital conflict). An example of a PBS plan for one family (Family 5) is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Multicomponent Positive Behavior Support Plan for Family 5 for Morning Routine, Homework Routine, Dinner Routine, and Restaurant Routine

| Setting Event Strategies |

| 1. Ensure that HJ goes to bed on time and gets sufficient sleep. |

| 2. In morning, before starting morning routine, engage in gentle interactions with HJ that help wake him. |

| 3. Use visual schedules to increase predictability about routine steps, expectations, length, and rewards. |

| 4. Embed preferred items and activities in routines (e.g., favorite breakfast food, preferred homework topic). |

| 5. Ensure that HJ spends quality time with father. |

| 6. If negative event occurs at school, to neutralize negative effects, when he arrives home talk with HJ, prompt deep breathing, and/or give treat. |

| 7. If HJ is tired, provide brief rest and/or snack. |

| 8. I f HJ is ill, reduce demands and increase choice. |

| Preventive Strategies |

| 1. Provide advanced warning (5 min, 1 min) before starting a routine or transitioning to non-preferred activity. |

| 2. Offer choices to encourage cooperation (e.g., breakfast or dinner foods, homework topic, rewards). |

| 3. Review visual schedule and agreed upon reward prior to starting a routine. |

| 4. Use positive contingencies to motivate cooperation (e.g., “Eat dinner and then you can have dessert”). |

| 5. Use stimulus fading to increase food acceptance (i.e., small amount gradually increased to typical amount). |

| 6. Pre-correct (i.e., remind, prompt and/or briefly rehearse) desired behavior and alternative replacement behavior. |

| 7. Provide non-contingent attention every 2-3 minutes. |

| Teaching Strategies |

| 1. Teach routine specific skills (e.g., writing skills, table manners, asking appropriate questions) using: (a) self-monitoring checklists; and (b) direct instruction methods (i.e., model, lead, test). |

| 2. Review social stories to provide information about routine expectations and parents’ perspective. |

| 3. Teach HJ to use appropriate language to achieve his wants and needs (e.g., asking for a break or help; asking for less food; asking to leave dinner table). |

| Consequence Strategies |

| 1. Provide praise, positive attention, and/or preferred item or activity contingent on routine related desired behavior. |

| 2. Provide break, help, less work, or less food contingent on HJ asking. |

| 3. Actively ignore and redirect minor problem behavior, or use a safety signal (e.g., “Eat one more bite, then you can have a break”). |

| 4. Withhold reinforcement for major problem behavior: (a) calmly and succinctly give one warning of loss of reward if behavior continues; (b) for escape-motivated problem behavior, maintain task demand; (c) for attention motivated problem behavior, do not discuss or scold; and (d) if behavior continues, withhold access to previously agreed upon reward (e.g., preferred food or activity). |

Implementation plan

An implementation plan was developed in collaboration with families. The implementation plan defined: (a) training materials and support activities that would be used to teach family members to implement behavior support strategies (e.g., written PBS plan, implementation checklist, in vivo coaching); (b) roles and responsibilities; and (c) a timeline for completing initial training in target routines.

Implementation support

Parents were taught to implement the PBS plan for each routine across two subphases: (a) initial training; and (b) maintenance support.

Initial training

Training and support was provided in one routine at a time. During initial training, interventionists provided direct in vivo support to parents by modeling and coaching the use of behavior support strategies, and indirect support during meetings in which plan strategies were discussed and role-played, and solutions for ongoing problems were generated. For three families in which coercive processes in target routines were entrenched, intensive 1:1 intervention with the focus child began with or was later initiated by the interventionist(s) in the first and/or second target routines. Initial training sessions per family averaged 1.2 per week, with a total average across families of 102.7 hours and 76.6 sessions across 107.4 weeks.

Maintenance support

Maintenance support was sequentially introduced to target routines for each family after initial training probes evidenced substantial improvement in problem behavior and steps completed (i.e., less than 10% of intervals of problem behavior; at or near 80% steps completed). At the start of maintenance support for each routine, the interventionist collaborated with the child's parents to develop a relapse prevention plan. During maintenance support, interventionists provided parents with brief coaching before a routine began, coaching during the routine as needed, and feedback after a routine was completed. During problem solving meetings parents were encouraged to solve problems on their own. Interventionists also taught and encouraged parents to generalize the use of support plan strategies to non-trained settings. Maintenance support per family averaged one session per 5.8 weeks, with a total average across families of 32.4 hours and 39.3 sessions across 113.3 weeks.

Follow-up

The follow-up phase was conducted with 8 of 10 families. With seven families, follow-up observations were conducted from October 2008 to December 2010. For these families, follow-up measurement began at 3 months postintervention and concluded at 11 months postintervention for Family 4; 12 months post-intervention for Families 1, 7, and 8; 18 months postintervention for Families 3 and 5; and 24 months post-intervention for Family 2. For Family 6, follow-up measurement was conducted at 17 months postintervention. Sixty-one probes were conducted, with an average of 7.6 observations per family (range 1 - 13). Follow-up support was provided if a probe showed regression in child behavior.

The study was approved by and conducted in compliance with the institutional review boards of the primary and consortium universities. A Data Safety and Monitoring Plan (DSMP) review was conducted yearly by the PI and Co-I with the assistance of an external examiner and parent consultant. The review evaluated the quality of videotaped observations, interobserver agreement, data based decision-making, behavior support plans, implementation support, and the social validity of research procedures. A yearly summary with recommendations informed improvements in research and intervention procedures.

Measures

Trained observers at both sites conducted observation sessions in family routines using mini-DV video cameras. Before an observation session, the observer read an operational definition of the routine to the child's parents. Parents were informed that they could take a break during the observation session and that they could terminate the observation session at any time. An observation session continued until: (a) the parent had attempted to do the routine for 10 to 15 minutes; (b) the child engaged in dangerous behavior that required immediate termination of the observation session; or (c) the routine was successfully completed. A total of 607 direct observation sessions were completed, with 238 during baseline, 156 during initial training, 152 during maintenance support, and 61 during follow-up. Across the course of the study, families participated in an average of 60.7 observation sessions (range 35–81), with an average of 9.8 observation sessions per year (range 7.2–12.2).

Following a videotaped observation, the observation was downloaded onto a computer in a lab in preparation for coding. To code child problem behavior and routine steps completed, coders used a paper-and-pencil data recording system while observing the video file on a computer monitor using Windows Media Player. To code parent-child interaction, coders observed the video file on the computer monitor using the Observer 5.0 software program (Noldus, Trienes, Hendriksen, Jansen, & Jansen, 2000) in concert with the Parent and Child Coding System (Lucyshyn et al., 2004). For 9 of 10 families, a random sample of 10 baseline and 10 intervention observations were selected, and for each observation session a 10-minute time sample was coded. For one family (Family 10) because intervention occurred in primarily one routine, 5 baseline and 5 intervention observations were selected and for each observation session an approximately 15-minute time sample was coded.

Dependent variables

Five dependent variables were measured and are defined below.

Problem behavior

Two categories of child problem behavior were defined: Minor and major. Minor included child non-compliance and child out of assigned area but engaged in acceptable behavior. Major included all externalizing problem behavior (e.g., screaming, physical aggression, destructive behavior). We defined total problem behavior as the percentage of 10-second intervals coded for one or more instances of either minor or major problem behavior (partial-interval or one-zero sampling; see Bakeman & Quera, 2011).

Routine steps completed

For each of the 36 routines in the study, routine steps and criteria for successful completion were defined in collaboration with families. We defined routine steps completed as the percentage of total steps in the routine that were coded as successfully completed. A routine was considered successful if problem behavior was less than 10% of intervals and trivial, and steps completed were at or near 80% steps completed.

Coercive and constructive processes of parent-child interaction

Two coercive patterns of parent-child interaction were defined, consistent with Patterson's (1982) coercive family process theory. In routines where parental requests and demands are common, a 4-step escape-driven coercive process was defined. In routines where a parent is busy and cannot readily attend to the child, a 4-step attention-driven coercive process was defined. Constructive patterns of parent-child interaction were defined based on logical inference. A 4-step constructive process was defined for routines in which parent requests and demands are common, and an alternative 4-step constructive process was defined for routines in which a parent is busy and cannot readily attend to the child.

Parent and Child Coding System

We used the Parent and Child Coding System (PACCS; Lucyshyn, Laverty et al., 2007) to measure coercive and constructive processes. PACCS is an observational coding system that is based on guidelines for the sequential analysis of dyadic interaction (Bakeman & Gottman, 1997). It is a “macro” coding system consisting of 10 parent behavior categories (e.g., Negative Attention, Request/Demand, Physical Assistance) and 10 child behavior categories (e.g., Problem Behavior, Non-comply, Comply). Mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories are organized in hierarchical order for both members of the dyad.

Data entry

For each of the 10 baseline and 10 intervention video files for each family, a trained coder used a jog and shuttle keyboard to enter parent and child codes, in the sequence of their occurrence, into Observer 5.0 (Noldus et al., 2000). These data were then merged for each family into: (a) 10 aggregate baseline files consisting of a random sample of observation sessions across family routines during baseline; and (b) 10 aggregate intervention files consisting of a random sample of observation sessions across family routines during intervention. Aggregate files represented routines in which an escape-driven or an attention-driven coercive process was hypothesized to exist during baseline, and a constructive process was hypothesized to emerge during intervention.

Following the merging of files within baseline and intervention phases for each family, we used the Cycles software program (Bakeman, 2000) to convert sequences of parent-child interaction codes into a series of parent-child behavior cycles. Each cycle consisted of one or more parent codes followed by one or more child codes, with the next parent code after a child code initiating the next cycle. This resulted in a multicode event data file. Each event or cycle contained at least one parent and at least one child code.

Sequential analysis

Following the creation of these files, we used the General Sequential Querier software program (GSEQ; Bakeman & Quera, 1995) to construct 2 × 2 tables from which we derived measures to test our hypotheses. Pairs of cycles were tallied, separately for each family at baseline and intervention. A tally was added to row 1 if the cycle contained hypothesized parent-child interaction (i.e., first two steps in four-step process) and to row 2 if not. Similarly, a tally was added to column 1 if a cycle at a specified lag contained other hypothesized parent-child interaction (i.e., last two steps in four-step process) and to column 2 if not. Based on previous sequential analyses with families, we hypothesized that escape driven coercive processes could occur between lags 1 and 4, and attention driven coercive or constructive processes could occur between lags 1 and 2 (e.g., Given a parent request/demand followed by child problem behavior, the parent will withdraw or reduce the request/demand and the child will terminate or reduce problem behavior, between lags 1 and 4). Based on the tallies in the 2 × 2 tables, we generated four measures for each family at baseline and at intervention. These are defined below.

1. Total number of pairs of parent-child interactions

This was measured as the sum of all parent-child cycles tallied across the four cells of the 2 × 2 table.

2. Percentage of 2-step processes

For hypothesized escape-driven coercive processes, this was the percentage of cycles containing a parent request/demand followed in the same cycle (i.e., a non-lagged cycle) by child problem behavior (%PRD-CPB). For attention-driven coercive processes, this was the percentage of cycles containing parent busy with other tasks followed in the same cycle by child problem behavior (%PBO-CPB). For hypothesized constructive processes in routines in which parent requests/demands were common, this was the percentage of cycles containing a parent request/demand followed in the same cycle by child compliance (%PRD-CCO). For constructive processes in routine in which parents were busy with other tasks, this was the percentage of cycles containing parent busy with other tasks followed in the same cycle by child appropriate behavior (%PBO-CAB).

3. Percentage of 4-step processes

For hypothesized escape driven coercive processes, this was the percentage of tallies containing parent demand and child problem behavior (PRD-CPB) in row 1, followed by parent withdraws or reduces demand and child terminates or reduces problem behavior (PWR-CTR) in column 1 (%PRD-CPB-PWR-CTR). For attention driven coercive processes, this was the percentage of tallies containing parent busy/occupied and child problem behavior (PBO-CPB) in row 1, followed by parent gives attention and child terminates or reduces problem behavior (PAT-CTR) in column 1 (%PBO-CPB-PAT-CTR). For hypothesized constructive processes in routines in which parent requests/demands were common, this was the percentage of tallies containing parent demand and child compliance (PRD-CCO) in row 1, followed by parent positive attention and child appropriate behavior (PPA-CAB) in column 1 (%PRD-CCO-PPA-CAB). For constructive processes in routines in which parents were busy, this was the percentage of tallies containing parent busy/occupied and child appropriate behavior (PBO-CAB) in row 1, followed by parent positive attention and child appropriate behavior (PPA-CAB) in column 1 (%PBO-CAB-PPA-CAB).

4. Odds ratio

For 4-step escape-driven coercive processes, the odds ratio indicated whether PWR-CTR was more likely when the previous non-lagged cycles contained PRD-CPB than when not. For 4-step attention driven coercive processes, the odds ratio indicated whether PAT-CTR was more likely when the previous non-lagged cycle contained PBO-CPB than when not. For 4-step constructive processes in routines in which requests/demands were common, the odds ratio indicated whether PPA-CAB was more likely when the previous non-lagged cycle contained PRD-CCO than when not. For 4–step constructive processes in routines in which the parent was busy, the odds ratio indicated whether PPA-CAB was more likely when the previous non-lagged cycle contained PBO-CAB than when not.

Social validity of PBS approach

Parents evaluated the social validity of the family centered PBS approach (Schwartz & Baer, 1991). A 10-item instrument with a 5-point Likert-scale (1 = disagree; 5 = agree) was used. Ten families completed social validity evaluations during intervention while seven families did so during follow-up. The social validity questionnaire was administered to parents 2–6 times during intervention and 1–2 times during follow-up. Average ratings across items were calculated for each family and served as summative ratings of social validity.

Interobserver agreement

For problem behavior and routine steps completed data, three interventionists at the BC site served as interobserver agreement (IOA) coders for eight families, while one doctoral student interventionist at the NJ site served as IOA coder for two families. For parent-child interaction data, the Project Coordinator and three research assistants at the BC site served as IOA coders for all 10 families. For problem behavior and steps completed data, IOA sessions were held for 40% and 39% of observation sessions, respectively, balanced across families and routines. Average percentage agreement for major problem behavior was 95%. Average percentage agreement for minor problem behavior was 96%. Average agreement for routine steps completed was 94%. For parent-child interaction data, IOA sessions were held for 20% of the observation sessions randomly sampled across baseline and intervention phases, stratified across families and routines. Using the reliability program of Observer 5.0, a Kappa statistic (Cohen, 1960) and percentage agreement score were calculated for parent and child behavior categories (Lucyshyn et al., 2004; Noldus et al., 2000). Kappa was .73 and .69, and average percentage agreement scores were 79% and 75% across parent and child behavior categories, respectively. Interpretation of Kappa depends on the number of categories; for 20 codes whose frequencies are moderately variable, Kappa scores of .62 result when observers are 80% accurate and of .71 when 85% accurate (see Bakeman & Quera, 2011). In dyadic interaction research, interobserver agreement scores of 70% or above are considered acceptable (see Apsland & Gardner, 2003).

Data Analyses

Research designs

Multiple methods assessed the internal, external, and social validity of the approach, and the consequential validity of coercive processes in family routines as an ecological construct. Single case multiple baseline designs across routines for each family were used to evaluate the effects of the approach on child behavior and routine participation. Quasi-experimental group designs across the 10 families were employed to examine the statistical significance of changes from baseline to intervention in problem behavior and steps completed, and in coercive and constructive processes. For this purpose, a nonparametric statistic for repeated measures was used.

Single case design and analysis

Assessment and intervention with families was conducted in the context of a single case experimental or quasi-experimental research design (Barlow, Nock, & Hersen, 2009). For each family, a multiple baseline design across two to four settings (i.e., routines) was employed, using a multiple probe measurement technique. The design had three phases: Baseline, intervention (consisting of initial training and maintenance support), and follow-up. Following baseline measurement in target routines with each family, intervention was introduced in lagged fashion across routines. Single case visual analysis was used to evaluate the functional relation between the ecological, family-centered PBS approach and improvements in child problem behavior and routine steps completed. Visual analysis was supplemented with a repeated measures analysis to evaluate the statistical significance of changes across the 10 families in problem behavior and steps completed from baseline to initial training, and from initial training to maintenance support. For this purpose, we used the Wilcoxon signed rank test, a nonparametric test for two repeated measures.

Univariate analysis of coercive and constructive processes

A within subjects, repeated measures, quasi-experimental group design evaluated the effects of the approach for transforming coercive processes into constructive processes in family routines across the 10 families. Dependent measures were the number of cycles, the percentage of 2-step and 4-step parent-child cycles of interaction (e.g., %PRD-CPB; %PRD-CPB-PWR-CTR), and the odds ratio at baseline and intervention for coercive and constructive processes. We used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to evaluate the statistical significance of changes from baseline to intervention in coercive and constructive processes of parent-child interaction.

Results

Results for multiple dependent variables were used to evaluate: (a) the functional relation between implementation of the PBS approach and improvements in child behavior and routine participation; (b) the statistical significance of improvements in child behavior and steps completed across baseline and intervention; (c) the transformation of coercive into constructive processes in family routines; and (d) the social validity of the approach.

Problem Behavior and Routine Steps Completed

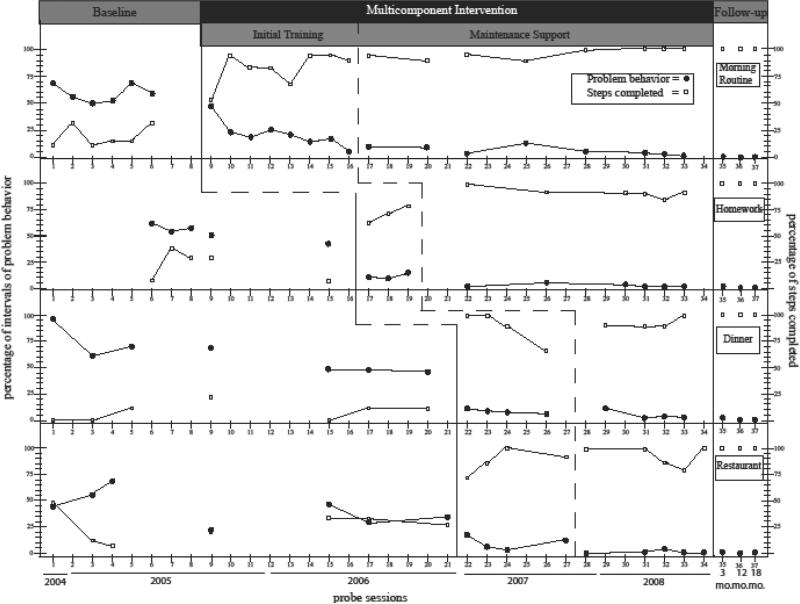

Table 2 summarizes results of implementation of the ecological, family centered PBS approach across baseline, intervention, and follow-up phases within the multiple baseline design across routines for each of the 10 families. A representative example of results from the multiple baseline design for one family (Family 5) is presented in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Results for Single Case Multiple Baseline Designs across Routines with 10 Families: Percentage (%) of Intervals of Child Problem Behavior and Percentage (%) of Routine Steps Completed.

| % of Intervals of Problem Behavior | % of Routine Steps Completed | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | # Routines | BL | IT | MS | F | # Basic Effects | BL | IT | MS | F | # Basic Effects | Evidence of Causal Effect | Limitations |

| 1 | 4 | 69.8 | 9.4 | 5.4 | 7.6 | 3 of 4 | 19.6 | 82.6 | 91.0 | 90.3 | 3 of 4 | Moderate | Drift in baseline in 4th routine for both dependent variables |

| 2 | 4 | 70.3 | 10.1 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 3 of 4 | 27.0 | 88.8 | 92.2 | 89.6 | 4 of 4 | Moderate | Drift in baseline in 4th routine for 1 dependent variable. |

| 3 | 3 | 53.8 | 13.8 | 7.0 | 1.8 | 3 of 3 | 34.3 | 87.2 | 93.5 | 97.9 | 3 of 3 | Strong | |

| 4 | 4 | 46.5 | 8.1 | 1.6 | 4.3 | 3 of 4 | 34.3 | 70.4 | 85.8 | 82.4 | 3 of 4 | Moderate | Drift in baseline in 4th routine for both dependent variables |

| 5a | 4 | 54.9 | 15.5 | 4.1 | 0.4 | 4 of 4 | 18.3 | 83.8 | 93.7 | 100.0 | 4 of 4 | Strong | |

| 6 | 4 | 61.0 | 14.2 | 7.1 | 1.8b | 3 of 4 | 25.5 | 77.4 | 84.6 | 90.9b | 3 of 4 | Weak | Overlapping data across baseline and intervention in 3rd routine; delayed intervention in 2 routines |

| 7 | 3 | 51.2 | 10.0 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 2 of 3 | 23.7 | 78.1 | 90.9 | 91.6 | 3 of 3 | Moderate | Drift in baseline in 3rd routine for 1 dependent variable |

| 8 | 2 | 46.6 | 7.5 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 2 of 2 | 37.5 | 89.1 | 92.0 | 96.8 | 2 of 2 | Not sufficient | Two strong basic effects, but only two baselines (routines) |

| 9 | 3 | 31.2 | 21.2 | 8.6 | — c | 1 of 3 | 49.4 | 73.9 | 95.8 | — c | 1 of 3 | None | Drift in baseline in 1st routine; overlapping data - baseline and intervention in 1st and 3rd routines |

| 10 | 2 | 26.6 | 14.9 | 10.9 | — c | 1 of 2 | 38.3 | 72.6 | 66.7 | — c | 1 of 2 | None | Insufficient data in 2nd routine |

| Total/M SD |

33 | 51.2 14.4 |

12.5 4.2 |

5.5 3.2 |

3.0 2.6 |

25 of 33 | 30.8 9.7 |

80.4 6.9 |

88.6 8.4 |

92.4 5.6 |

27 of 33 | 7 of 10 | |

Note. BL = Baseline; IT = Initial Training; MS = Maintenance Support; F = Follow-Up; M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation.

See Figure 1.

Follow-up data gathered in only one of four routines.

Follow-up data not gathered due to termination of study at consortium site due to end of funding cycle prior to follow-up phase.

Figure 1.

Percentage of intervals of problem behavior and percentage of steps completed for Family 5 across four routines. Results document a functional relation between implementation of the ecological, family centered PBS approach and improvements in child problem behavior and routine steps completed. Results across the four routines maintained at 3 to 18 months postintervention.

Overall, these data document substantial improvements in child problem behavior and routine steps completed from baseline to intervention for 9 of 10 families, and the maintenance of outcomes during follow-up 3 to 24 months postintervention for 8 of 10 families. Across the 10 families, problem behavior averaged 51.2% of intervals (range, 26.6% - 70.3%) during the baseline phase. During intervention, problem behavior decreased to an average of 12.5% of intervals (range, 7.5% - 21.2%) in the initial training subphase, and further decreased to an average of 5.5% of intervals (range, 1.4% - 10.9%) in the maintenance support subphase. The Wilcoxon signed rank test showed a statistically significant decrease in problem behavior across the 10 families from baseline to initial training, and from initial training to maintenance support (T = 0, Z = −2.80, p = .005 for both comparisons). During follow-up with 8 of 10 families, problem behavior further decreased to an average of 3.0% of intervals (range, 0.1% - 7.6%).

Routine steps successfully completed evidenced a reciprocal pattern of improvement across phases. During baseline, routine steps completed averaged 30.8% (range, 18.3 - 49.4%). During intervention, steps completed increased to an average of 80.4% (range, 70.4 - 89.1%) in the initial training subphase, and further increased to 88.6% (range, 66.7 - 95.8%) in the maintenance support subphase. The Wilcoxon signed rank test showed a statistically significant increase in routine steps completed across the 10 families from baseline to initial training (T= 0, Z = −2.80, p = .005), and from initial training to maintenance support (T = 2, Z = −2.48, p = .009). During follow-up with 8 of 10 families, improvements maintained at an average of 92.4% of steps completed (range, 82.4 - 100%). At the end of follow-up measurement with 8 families, 23 of 24 routines observed showed continued success, with modest regression in one routine for Family 5 at 6 months postintervention.

To evaluate the presence of a functional effect, rules of evidence for single case research were employed (i.e., demonstration of 3 basic effects at three different points in time, effects at or near point of intervention; minimal overlapping data across baseline and intervention phases; Barlow et al., 2009). Adhering to these rules, a strong causal effect was documented for two families (Families 3 and 5), a moderate causal effect was documented for four families (Families 1, 2, 4, and 7), and a weak causal effect was evidenced for one family (Family 6). No causal effect was demonstrated for three families (Family 8, 9 and 10). Absence of a causal effect for Family 8 was due to the presence of only two routines in the multiple baseline design. However, immediate, robust and durable basic effects were observed in both routines. Absence of a causal effect for Families 9 and 10 was due to drift in baseline data in one routine and overlapping data across baseline and intervention phases in two routines. Weak or nominal outcomes were associated with parent treatment nonadherence, family systems challenges (e.g., marital conflict), and/or shortcomings in PBS plan design and/or implementation support. Weak or nominal outcomes did not appear to be associated with children's level of adaptive functioning. Families of children who were low functioning (i.e., largely non-verbal with few adaptive behaviors) at the start of the study were equally distributed across children who experienced robust (Families 2, 3, and 4) or nominal (Families 9 and 10) outcomes by the conclusion of the study. Taken together, results provide documentation of the efficacy of the intervention approach but with reservation, recognizing that there are conditions in which the approach may not be sufficient for every family, or that plan design and/or implementation support may need to be improved.

Individual Family-Level Analyses of Coercive Processes

Results of the sequential analysis of escape-driven and attention-driven coercive processes for each of the 10 families across baseline and intervention conditions are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Percentage of Two-Step and Four-Step Coercive Processes, Odds Ratio for Four-Step Coercive Processes, and 95% Confidence Intervals during Baseline and Intervention Phases for Ten Families

| 4-Step Escape-Driven Coercive

Process | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

Intervention |

|||||||||

| Family | N | % PRD-CPB | %PRD-CPB-PWR-CTR | Odds Ratio | [95% CI] | N | % PRD-CBP | %PRD-CPB-PWR-CTR | Odds Ratio | [95% CI] |

| 1 | 648 | 33 | 6.0 | 1.93 | [1.21, 3.06] | 522 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | — |

| 2 | 712 | 39 | 11 | 1.47 | [1.03, 2.10] | 732 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 2.45 | [0.52, 11.59] |

| 3 | 935 | 10 | 3.2 | 1.95 | [1.22, 3.12] | 504 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 0.65 | [0.20, 2.08] |

| 5 | 843 | 15 | 5.0 | 1.78 | [1.18, 2.68] | 664 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 4.45 | [1.80, 11.02] |

| 6 | 787 | 26 | 4.2 | 1.78 | [1.12, 2.83] | 668 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | — |

| 7 | 742 | 20 | 6.1 | 1.70 | [1.14, 2.54] | 394 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 2.01 | [0.39, 10.19] |

| 4-Step Attention-Driven

Coercive Processes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

Intervention |

|||||||||

| Family | N | %PBO-CPB | %PBO-CPB-PAT-CTR | Odds Ratio | [95% CI] | N | %PBO-CPB | %PBO-CPB-PAT-CTR | Odds Ratio | [95% CI] |

| 4 | 559 | 10 | 5.2 | 2.61 | [1.49, 4.58] | 261 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 0.81 | [0.15, 4.26] |

| 8 | 597 | 11 | 3.2 | 1.75 | [0.99, 3.10] | 539 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | — |

| 9 | 581 | 21 | 12 | 2.48 | [1.65, 3.74] | 602 | 11 | 6.8 | 2.53 | [1.49, 4.28] |

| 10 | 309 | 11 | 7.1 | 2.80 | [1.31, 6.00] | 293 | 8.9 | 4.4 | 0.64 | [0.28, 1.43] |

Note. N is the number of cycles; %PRD-CPB is the percentage of cycles that contained a parent request or demand (PRD) followed by a child problem behavior (CPB) in that cycle. %PRD-CPB-PWR-CTR is the percentage of pairs of cycles that contained PRD-CPB in one cycle followed by parent withdraws or reduces demand and child terminates or reduces problem behavior (PWR-CTR) in the next 1 to 4 cycles. The odds ratio indicates whether PWR-CTR was more (>1) or less (<1) likely in the next 1 to 4 cycles if the preceding cycle contained PRD-CPB. Sequential analyses were at lag 1 except for two families. %PBO-CPB-PAT-CTR is the percentage of pairs of cycles that contained PBO-CPB in one cycle followed by parent delivering attention and child terminating or reducing problem behavior (PPA-CTR) in the next 1 to 2 cycles. The odds ratio indicates whether PAT-CTR was more (>1) or less (<1) likely in the next 1 to 2 cycles if the preceding cycle contained PBO-CPB. Analyses were at lag 1 except for one family. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that do not contain 1 are significant at the .05 level.

Escape driven coercive processes

The percentage of cycles that contained a parent request or demand followed by a child problem behavior (PRD-CPB) in that cycle declined from baseline to intervention for 6 of 6 families (Families 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7). The percentage of pairs of cycles that contained a PRD-CPB in one cycle followed by parent withdraws or reduces demand and child terminates or reduces problem behavior in the next cycle (PWR-CTR) likewise declined from baseline to intervention for 6 of 6 families. At baseline, for 6 of 6 families the odds that PWR-CTR would occur in a cycle were significantly greater when the previous cycle contained PRD-CPB (i.e., the CI for the odds ratio did not include 1). At intervention, only one odds ratio was significant. Taken together, the odds ratio results indicate that the 4-step escape-driven coercive process was operating at baseline but was disrupted at intervention.

Attention driven coercive processes

The percentage of cycles that contained parent busy with other tasks followed by a child problem behavior (PBO-CPB) in that cycle declined from baseline to intervention for 4 of 4 families (Families 4, 8, 9, and 10). The percentage of pairs of cycles that contained PBO-CPB in one cycle followed by parent gives attention and child terminates or reduces problem behavior in the next cycle (PAT-CTR) likewise declined from baseline to intervention for 4 of 4 families. At baseline for 3 of 4 families, the odds that PAT-CTR would occur in a cycle were significantly greater when the previous cycle contained PBO-CPB (i.e., the CI for the odds ratio did not include 1, and the CI for the one that did extended only to 0.99). At intervention, only one odds ratio was significant. Taken together, the odds ratio results indicate that the 4-step attention-driven coercive process was operating at baseline but was disrupted at intervention for 3 of 4 families.

Individual Family-Level Analyses of Constructive Processes

Results of the sequential analysis of constructive processes for each of the 10 families across baseline and intervention conditions are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Percentage of Two-Step and Four-Step Constructive Processes, Odds Ratio for Four-Step Constructive Processes, and 95% Confidence Intervals during Baseline and Intervention Phases for Ten Families

| 4-Step Constructive Process in

Routines in which Parent Requests/Demands are Common | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

Intervention |

|||||||||

| Family | N | % PRD-CCO | %PRD-CCO-PPA-CAB | Odds Ratio | [95% CI] | N | % PRD-CCO | %PRD-CCO-PPA-CAB | Odds Ratio | [95% CI] |

| 1 | 741 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0 | — | 522 | 13 | 5.2 | 2.70 | [1.57, 4.63] |

| 2 | 734 | 5.9 | 0.4 | 4.24 | [1.15, 15.65] | 733 | 37 | 8.7 | 2.71 | [1.80, 4.09] |

| 3 | 935 | 17 | 0.0 | 0 | — | 945 | 40 | 5.7 | 0.85 | [0.59, 1.22] |

| 5 | 843 | 7.9 | 0.6 | 2.24 | [0.83, 6.01] | 664 | 13 | 3.9 | 3.35 | [1.98, 5.68] |

| 6 | 787 | 10 | 0.8 | 2.77 | [1.08, 7.10] | 668 | 19 | 5.8 | 2.05 | [1.33, 3.18] |

| 7 | 729 | 9.3 | 0.3 | 0.74 | [0.17, 3.19] | 384 | 14 | 3.4 | 2.44 | [1.20, 4.95] |

| 4-Step Constructive Process in

Routines in which Parent is Busy | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

Intervention |

|||||||||

| Family | N | %PBO-CAB | %PBO-CAB-PPA-CAB | Odds Ratio | [95% CI] | N | %PBO-CAB | %PBO-CAB-PPA-CAB | Odds Ratio | [95% CI] |

| 4 | 570 | 31 | 6.7 | 0.80 | [0.53, 1.23] | 271 | 48 | 32 | 1.95 | [1.19, 3.20] |

| 8 | 597 | 9.4 | 2.2 | 1.18 | [0.62, 2.28] | 539 | 17 | 11 | 1.87 | [1.17, 2.99] |

| 9 | 581 | 30 | 6.7 | 1.37 | [0.89, 2.13] | 602 | 31 | 10 | 1.62 | [110, 2.39] |

| 10 | 309 | 31 | 17 | 1.12 | [0.69, 1.81] | 293 | 22 | 11 | 2.13 | [1.21, 3.75] |

Note. N is the number of cycles; %PRD-CCO is the percentage of cycles that contained a parent request or demand (PRD) followed by child compliance (CCO) in that cycle. %PRD-CCO-PPA-CAB is the percentage of pairs of cycles that contained PRD-CCO in one cycle followed by parent positive attention and child appropriate behavior (PPA-CAB) in the next 1 or 2 cycles. The odds ratio indicates whether PPA-CAB was more (>1) or less (<1) likely in the next 1 or 2 cycles if the preceding cycle contained PRD-CCO. Sequential analyses were at lag 1 except for one family. %PBO-CAB is the percentage of cycles that contained parent busy with other tasks followed by child appropriate behavior (PBO-CAB) in that cycle; %PBO-CAB-PPA-CAB is the percentage of pairs of cycles that contained PBO-CAB in one cycle followed by parent positive attention and child appropriate (PPA-CAB) in the next cycle (lag 1). The odds ratio indicates whether PPA-CAB was more (>1) or less (<1) likely in the next cycle if the preceding cycle contained PBO-CAB. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that do not contain the number 1 are significant at the .05 level.

Constructive processes in routines in which parent requests/demands are common

The percentage of cycles that contained a parent request/demand followed by child problem compliance (PRD-CCO) in that cycle increased from baseline to intervention for 6 of 6 families. The percentage of pairs of cycles that contained a PRD-CCO in one cycle followed by parent positive attention and child appropriate behavior (PRD-CCO-PPA-CAB) in the next cycle likewise increased from baseline to intervention for 6 of 6 families. At intervention, for 5 of 6 families, the odds that PPA-CAB would occur in a cycle were significantly greater when the previous cycle contained PRD-CCO. At baseline, only two odds ratios were significant. Taken together, the odds ratio results suggest that the 4-step constructive process in routines in which parent requests/demands were common was operating at intervention but not at baseline.

Constructive processes in routines in which parent is busy with other tasks

The percentage of cycles that contained parent busy with other tasks and child appropriate behavior (PBO-CAB) in that cycle increased from baseline to intervention for 3 of 4 families. The percentage of pairs of cycles that contained PBO-CAB in one cycle followed by parent positive attention and child appropriate behavior (PBO-CAB-PPA-CAB) in the next cycle likewise increased from baseline to intervention for 3 of 4 families. At intervention, for 4 of 4 families, the odds that PPA-CAB would occur in a cycle were significantly greater when the previous cycle contained PBO-CAB. At baseline, no odds ratios were significant. Taken together, odds ratio results suggest that the 4-step constructive process in routines where parents were busy with other tasks was operating at intervention but not at baseline.

Univariate Analysis of Coercive and Constructive Processes

Results of the univariate analysis of change across the 10 families in coercive and constructive processes from baseline to intervention are presented in Table 5. The Wilcoxon signed rank test evaluated changes from baseline to intervention in total number of cycles of parent-child interaction, percentage of coercive processes, and percentage of constructive processes. For both coercive and constructive processes, the total number of cycles of parent-child interaction evidenced a statistically significant decrease from baseline to intervention (p = .047 and .028, respectively). The percentage of 2- and 4-step coercive processes showed statistically significant decreases from baseline to intervention (p = .005 for both). In contrast, the percentage of 2- and 4-step constructive processes evidenced statistically significant increases from baseline to intervention (p = .022 and .037, respectively). In terms of magnitude of change, results represent a 4.2 fold decrease in the percentage of 4-step coercive processes from baseline to intervention, and a 2.8 fold increase in the percentage of 4-step constructive processes from baseline to intervention. However, across the 10 families changes in odds ratios from baseline to intervention were not statistically significant (p = .24 and .093 respectively)

Table 5.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Wilcoxon Signed Rank Tests of Effects of Ecological, Family Centered PBS on Changes in Coercive and Constructive Processes from Baseline to Intervention Phases

| Baseline | Intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | Wilcoxon T | Z | p | n changed |

| Coercive processes | ||||||||

| Number of cycles | 671 | (175.5) | 518 | (159.6) | 5 | –2.29 | .022 | 8 |

| 2-step processes (%) | 19.4 | (10.3) | 3.40 | (3.60) | 0 | –2.80 | .005 | 10 |

| 4-step processes (%) | 6.30 | (3.00) | 1.50 | (2.39) | 0 | –2.80 | .005 | 10 |

| Odds ratio | 2.02 | (0.44) | 1.35 | (1.47) | 16 | –1.17 | .24 | 6 |

| Constructive processes | ||||||||

| Number of Cycles | 683 | (176) | 562 | (208 | 6 | –2.19 | .028 | 8 |

| 2-step processes (%) | 15.2 | (11.3) | 25.4 | (12.7) | 5 | –2.24 | .025 | 9 |

| 4-step processes (%) | 3.40 | (5.30) | 9.60 | (8.50) | 7 | –2.14 | .032 | 9 |

| Odds Ratio | 1.45 | (1.31) | 2.17 | (0.69) | 11 | –1.68 | .093 | 8 |

Note. N = 10. T is the sum of the negative or positive ranks, whichever is smaller, for the Wilcoxon signed-rank test; n is the number of families whose individual mean changed in the direction of the group mean change during intervention. For definitions of 2- and 4-step coercive and constructive processes, see section “Coercive and Constructive Processes of Parent-Child Interaction”.

Social Validity

During the intervention phase, across 10 families and 69 social validity evaluations (M = 6.9 evaluations per family, range 2–11), parents’ average social validity rating (1 = disagree; 5 = agree) was 4.6 (average range 3.7-5.0). During the follow-up phase, across 7 families and 16 social validity evaluations (M = 2.3 evaluations per family, range 2-4) parents’ average social validity rating rose slightly to 4.7 (average range 3.6-5.0). Overall, parents found the goals, procedures, and outcomes of the family centered PBS approach to be acceptable and important.

Discussion

Results across multiple methods and measures provide evidence for the internal, external, and social validity of the ecological, family centered PBS approach. Single case design results documented causal effects for seven of ten families and strong basic effects for one family. Overall, these data showed an 89.5% reduction in problem behavior from baseline to intervention, and a 65.2% increase in routine steps completed. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test showed these improvements to be statistically significant. Follow-up results 3 to 24 months postintervention with 8 families offer evidence of durability and sustainability. Across 61 follow-up observations in 24 routines, 93% of observations (57 of 61) evidenced maintenance or further improvement. Preliminary evidence of external validity may be seen in the largely positive outcomes achieved by children with different types and levels of developmental disability (i.e., low and high functioning autism, Asperger Syndrome, moderate intellectual disability) by families of diverse cultural backgrounds (i.e., Chinese, Japanese, Iranian), and by families experiencing family systems challenges (i.e., anxiety disorder, marital conflict). Social validity results indicated that goals, procedures, and outcomes were acceptable to families. This evidence, however, is tempered by nominal to modest outcomes for Families 9 and 10, modest to moderate regression in two of four routines for Family 6 during maintenance support and in one of three routines for Family 4 during follow-up, and lack of or minimal follow-up data for Families 6, 9, and 10.

Sequential and univariate analysis results strengthen the evidential validity of the construct of parent-child interaction in family routines, and offer preliminary empirical evidence of the consequential validity of the construct. The use of the ecological construct to guide behavior support plan design was associated with the transformation of four-step coercive processes into four-step constructive processes in 9 of 10 families. These results offer preliminary empirical support for an ecological unit of analysis for behavioral intervention with families of children with developmental disabilities that includes the function of child problem behavior, coercive and constructive patterns of parent-child interaction, and the activity settings of family life.

Nine of 10 families reported positive outcomes that went beyond target routines. Collateral effects included: (a) generalization of positive child behavior to non-trained settings (e.g., grocery shopping); (b) increases in complexity of child behavior (e.g., showing a sense of humor); (c) parents adapting strategies in novel settings (e.g., creating visual supports during summer vacation); (d) improvements in child relationship with sibling and/or father; (e) families taking summer vacations; and (f) parents finding employment or enrolling in post-secondary education program. A few parents also reported negative side effects: (a) siblings feeling upset due to receiving less parental attention; (b) a father feeling uncomfortable with the number of people in the home on a weekly basis; and (c) parents losing interest in a target routine but feeling obligated to continue doing the routine. When a family reported side effects, interventionists worked with the family to ameliorate these effects.

The study strengthens the empirical literature in four ways. First, it adds to a modest body of empirical evidence for the efficacy, acceptability, and durability of family centered PBS with families of children with developmental disabilities and severe problem behavior (Buschbacher et al., 2004; Lucyshyn et al., 2007). Second, the study extends the generalizability of the approach by showing that it can be effective, acceptable, and durable with families of diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, and with families experiencing significant family systems challenges. Third, the study provides additional empirical support for the family activity setting as a unit of analysis that contributes to the empowerment of families to effectively support their child with a disability within the natural contexts of family life. Finally, the study further extends the work of Patterson et al. (1992) on the presence of coercive processes in families of young boys who engage in aggressive behavior to families of boys and girls with developmental disabilities and problem behavior.

The study makes three unique contributions. First, results based on hundreds of observations contribute to theory about the etiology of child problem behavior in family contexts. Young children with developmental disabilities may experience common stimuli, simple tasks and activities, and normative parental expectations as aversive. When parents attempt to introduce their child to normative expectations in typical routines (e.g., complying to requests, waiting for attention), the child may respond with problem behavior. If parents maintain the expectation, the child may escalate. Parents may then respond in ways that terminate problem behavior (i.e., by withdrawing the demand or delivering attention). Following these parent responses, children typically terminate or reduce problem behavior, which serves as negative reinforcement for the parent. Doing so also may have a qualitative dimension in that parents may experience submitting and thus terminating problem behavior as showing care for the child (Traustadottir, 1991). Finally, when coercive processes take hold across family routines, they affect the architecture of family life. Family activity patterns are corroded such that daily and weekly routines become: (a) typical in structure but chronically problematic; (b) distorted in structure in a way that avoids problem behavior; and/or (c) absent to avoid problem behavior altogether. In summary, coercive processes in families of children with disabilities appear to develop within the prosaic activities of everyday family life as caring parents attempt to include the child in the routines of daily life, but face persistent challenges when doing so.

Second, the study provides the first empirical demonstration of the transformation of 4-step coercive processes into 4-step constructive processes in family routines. In addition, while 9 of 10 families evidenced a transformation of parent-child interaction from coercive to constructive within target routines, multiple methods suggest that 5 of 10 families experienced broader transformational change (Families 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8), defined by Overton (2006) as durable change in the form and structure of a system, including an increase in novelty and complexity. For these families, empirical results paired with parent reports of collateral effects suggest that the form and structure of parent-child interaction within the family system evidenced durable improvements with an increase in the novelty and complexity of family activity patterns.

Third, the study provides the first empirical documentation of 4-step constructive processes of parent-child interaction in family routines. An aim of researchers in the field of positive psychology has been to measure human processes that are associated with mental health (Snyder, Lopez, & Pedrotti, 2011). This suggests that coercion theory may be further advanced by the development of a theory of constructive processes in which micro-interactional family processes reciprocally reinforce adaptive child behavior and effective parenting practices.

The study offers five implications for assessment and intervention with families of children with disabilities and problem behavior. First, assessment of coercive family processes should be included as part of a functional assessment. Second, to ameliorate coercive processes, establishing a strong therapeutic alliance with the family is of critical importance. Third, the family activity setting appears to be a potent unit of analysis for understanding family contexts and for designing survivable interventions. Fourth, a broad assessment of family ecology may contribute to the development of PBS plans that are survivable in family contexts. Fifth, interventionists will benefit from receiving clinical supervision from a clinical or counseling psychologist or social worker with expertise in evidence-based practices for families experiencing family systems challenges such as an anxiety disorder or marital conflict.

Four limitations require acknowledgement. First, the absence of a functional effect for 3 of 10 families moderates single case design evidence of internal and external validity. Second, the absence of follow-up data with Families 9 and 10, the weak functional effect and minimal follow-up data with Family 6, and regression in one of three routines during follow-up for Family 4 restrains the claim that the approach is associated with durable and sustainable outcomes. A third limitation is the absence of a sequential analysis of coercive and constructive processes during follow-up. Finally, although the approach was effective in improving child behavior, parent-child interaction, and participation in target routines for 7 of 10 families, and was associated with strong basic effects for one additional family, it was not efficient in terms of time and sessions required. This may be attributed to three factors: (a) the use of a multiple baseline design that constrained the pace at which change could be promoted; (b) the tenacity of coercive processes; and (c) family systems challenges.

Future research may consider five areas. First, studies that examine the effectiveness of the approach should use research designs that do not detract from efficiency, such as a randomized control trial. Second, to further enhance efficiency a technology of generalization promotion should be employed when conducting assessments and designing PBS plans. Third, implementation support to families should use new communication technologies such as web-based training modules and Skype®. Fourth, research should continue to extend the generalizability of family centered PBS to families of diverse cultural backgrounds, and to families experiencing family systems challenges. Finally, research should extend sequential analysis to a follow-up phase to directly evaluate the durability of improvements in parent-child interaction.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to the families who participated in the study for their abiding trust, collaboration, and effort. We thank Robert Horner and Michael Stoolmiller for their contributions as formal consultants to the project. We thank Lauren Elkinson and Laura Green for their contributions as family interventionists. We thank Bruno Zumbo and Michael Knox for their contributions as Data Safety and Monitoring Plan Evaluators. We thank Clair Shuman and Kathy Roberson for their contributions as parent consultants. We also thank the following individuals for their contributions: Paul Yovanoff, Gerald Patterson, Edward Carr, Glen Dunlap, George Singer, Deborah Pugh, Pat Mirenda, Ann Turnbull, and Rud Turnbull. We also wish to thank the many research assistants and volunteers who contributed to the conduct of the study. The research project was supported by grant 5R01HD041671 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the University of British Columbia (UBC). The project was additionally supported through a consortium agreement with Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Contributor Information

Joseph M. Lucyshyn, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology and Special Education, Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. V6T1Z4

Brenda Fossett, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology and Special Education, Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. V6T1Z4.

Roger Bakeman, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA.

Christy Cheremshynski, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology and Special Education, Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. V6T1Z4.

Lynn Miller, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology and Special Education, Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. V6T1Z4.

Sharon Lohrmann, The Boggs Center, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ.

Lauren Binnendyk, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology and Special Education, Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. V6T1Z4.

Sophia Khan, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology and Special Education, Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. V6T1Z4.

Stephen Chinn, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology and Special Education, Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. V6T1Z4.

Samantha Kwon, Department of Educational and Counseling Psychology and Special Education, Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. V6T1Z4.

Larry K. Irvin, College of Education, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR

References

- Albin RW, Lucyshyn JM, Horner RH, Flannery KB. Contextual fit for behavior support plans: A model for “goodness of fit. In: Kern Koegel L, Koegel R, editors. Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community. Paul H. Brookes; Baltimore: 1996. pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Aspland H, Gardner F. Observational measures of parent-child interaction: An introductory review. Child and Adolescent Health. 2003;8:136–153. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM. “Exemplary services to what outcome?” Review of education of learners with severe handicaps: Exemplary service strategies. In: Horner RH, Meyer LH, Fredericks BD, editors. The Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. Vol. 11. Paul H. Brookes; Baltimore: 1986. 1986. pp. 145–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R. Cycles. Unpublished computer software. Georgia State University. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Gottman J. Observing interaction: An introduction to sequential analysis. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Quera V. Analyzing interaction: Sequential analysis with SDIS and GSEQ. New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Quera V. Sequential analysis and observational methods for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edelbrock C. Behavior problems and parenting stress in families of three-year old children with and without developmental disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2003;107:433–444. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2002)107<0433:BPAPSI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow D, Nock M, Hersen M. Single-case experimental designs: Strategies for studying behavior change. 3rd ed. Pearson Education Inc.; Boston: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley BE, Blacher J. Parental reasons for out-of-home placement of children with severe handicaps. Mental Retardation. 1991;29:275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschbacher P, Fox L, Clarke S. Capturing desired family routines: A parent-professional behavioral collaboration. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2004;29:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Carr EG. The expanding vision of positive behavior support: Research perspectives on happiness, helpfulness, and hopefulness. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2007;9:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, Fox L. A demonstration of behavioral support for young children with autism. Journal of Positive Behavioral Intervention. 1999;1:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman MA, Condillac RA, Tough S, Hunt S, Griffiths D. Effectiveness of community positive behavioral intervention for persons with developmental disabilities and severe problem behavior disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33:377–398. [Google Scholar]

- Gallimore R. Behavior change in the natural environment: Everyday activity settings as a workshop of change. In: O'Donnell CR, Yamauchi LA, editors. Culture and context in human behavior change: Theory, research, and applications. Peter Lang; New York: 2005. pp. 207–231. [Google Scholar]

- Lucyshyn JM, Albin RW, Horner R, Mann J, Mann J, Wadsworth G. Family implementation of positive behavior support with a child with autism: A longitudinal, single case experimental and descriptive replication and extension. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2007;9:131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Lucyshyn JM, Albin RW, Nixon CD. Embedding comprehensive behavioral support in family ecology: An experimental, single-case analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:241–251. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucyshyn JM, Binnendyk L, Fossett B, Cheremshynski C, Lohrmann S, Elkinson L, Miller L. Toward an ecological unit of analysis in behavioral assessment and intervention with families of children with developmental disabilities. In: Sailor W, Dunlap G, Sugai G, Horner R, editors. Handbook of positive behavior support. Series: Issues in Child Clinical Psychology. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 73–109. [Google Scholar]

- Lucyshyn JM, Irvin LK, Blumberg ER, Laverty R, Horner RH, Sprague JR. Validating the construct of coercion in family routines: Expanding the unit of analysis in behavioral assessment with families of children with developmental disabilities. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 2004;29:104–121. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.29.2.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucyshyn J, Laverty R, Khan S, Boonstra J, Irvin LK, Blumberg ER, Sprague J, Horner R. Parent and child coding manual [Version 5.0] 2007 Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Messick S. The once and future issues of validity: Assessing the meaning and consequences of measurement. In: Wainer H, Braun HI, editors. Test validity. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Noldus LPJJ, Trienes RJH, Hendriksen AHM, Jansen H, Jansen RG. The Observer Video Pro: New software for the collection, management, and presentation of time-structured data from videotapes and digital media files. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2000;32:197–206. doi: 10.3758/bf03200802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill RE, Horner RH, Albin RW, Sprague JR, Storey K, Newton JS. Functional assessment and program development for problem behavior: A practical handbook. Brooks/Cole Publishing; Pacific Grove, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Overton WF. Developmental psychology: Philosophy, concepts, and methodology. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of development. 6th Ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 18–88. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family processes. Castalia Publishing Co.; Eugene, OR: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Repp A, Horner RH. Functional analysis of problem behavior: From effective assessment to effective support. Wadsworth Publishing; Belmont, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Mazzucchelli T, Studman L, Sanders MR. Behavioral family intervention for children with developmental disabilities and behavioral problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:180–193. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz IS, Baer DM. Social validity assessments: Is current practice state of the art? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:189–204. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Lopez JT, Pedrotti JT. Positive psychology: The scientific and practical exploration of human strengths. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Traustadottir R. Mothers who care: Gender, disability, and family life. Journal of Family Issues. 1991;12:211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull AP, Ruef MB. Family perspectives on problem behavior. Mental Retardation. 1996;34:280–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]