Abstract

Endothelial dysfunction is considered one of the etiological factors of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). An inflammatory process leads to functional and structural changes in the vascular endothelium. An increase of leukocyte adhesiveness and leukocyte diapedesis, as well as an increased vascular smooth muscle tone and procoagulant activity is observed. Structural changes of the vascular endothelium comprise as well capillary and venule remodeling and proliferation of endothelial cells. Hypoxia in the inflammatory area stimulates angiogenesis by up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast growth factor and tumor necrosis factor-α. Inflammatory mediators also alter the lymphatic vessel function and impair lymph flow, exacerbating tissue edema and accumulation of dead cells and bacteria. The endothelial dysfunction might be diagnosed by the use of two main methods: physical and biochemical. Physical methods are based on the assessment of large arteries vasodilatation in response to an increased flow and receptors stimulation. Flow-mediated vasodilatation (FMD) is the method that is the most widely used; however, it is less sensitive in detecting early changes of the endothelium function. Most of the studies demonstrated a decrease of FMD in IBD patients but no changes in the carotic intima-media thickness. Biochemical methods of detecting the endothelial dysfunction are based on the assessment of the synthesis of compounds produced both by the normal and damaged endothelium. The endothelial dysfunction is considered an initial step in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in the general population. In IBD patients, the risk of cardiovascular diseases is controversial. Large, prospective studies are needed to establish the role of particular medications or dietary elements in the endothelial dysfunction as well to determine the real risk of cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Cytokines, Diagnosis, Endothelial dysfunction, Inflammatory bowel diseases, Inflammation, Microvasculature

Core tip: Endothelial dysfunction seems to play an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Inflammatory process leads to functional and structural changes in the vascular endothelium and in consequence its activation. It may contribute to cardiovascular complications, however, in IBD patients, the risk of cardiovascular disease is still controversial. Some of immunomodulatory medications used in IBD treatment may decrease the risk of endothelial dysfunction. In this review article, we present the role of the endothelium in the inflammatory process, diagnostic methods of its dysfunction and current knowledge of the cardiovascular disease risk in IBD.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has a multifactorial etiology that has not been fully elucidated. Patients with IBD are genetically predisposed to pathological interactions between intestinal microflora and the immunological system[1]. Changes in the balance between regulatory and inflammatory cytokines lead to maintenance of the inflammatory process[2]. Dysfunction of the endothelium has also been considered an etiological factor.

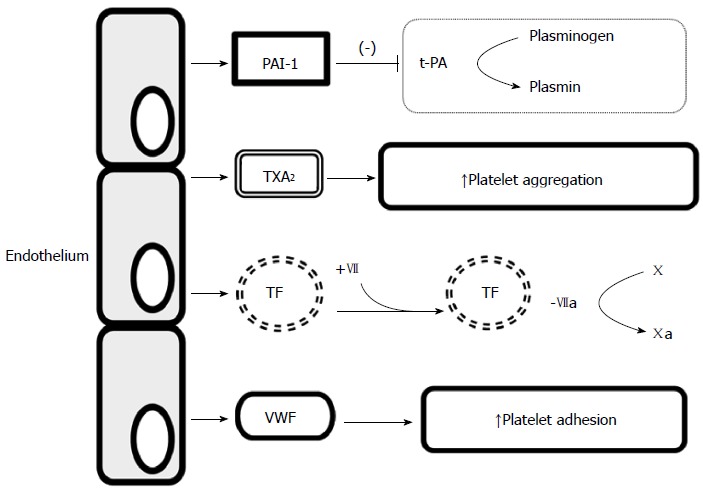

The endothelium is a highly specialized, single-layered epithelium that lines internal surfaces of blood and lymph vessels and cardiac valves[3,4]. It plays a significant role in tissue flow, blood coagulation, regulation of substance transport across vascular walls, and regulation of the number and type of leukocytes migrating across vascular walls[3,5]. Endothelial cells are characterized by high metabolic activity, basement membrane-producing elements, intercellular components, and numerous substances that regulate blood vessel function, such as nitric oxide (NO), endothelin 1, prostacyclin 2, von Willebrand factor (vWF), and cellular adhesion molecules (CAMs)[3,6] (Table 1). Under physiological conditions, the endothelium has dilating effect on vessels, prevents their excessive permeability, and prevents adhesion and aggregation of blood platelets and leukocytes. It also regulates fibrinolysis and the coagulation pathway[4,7] (Figures 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Factors released by endothelium

| Factors regulating vascular tension | Factors regulating angiogenesis and cells proliferation | Factors regulating coagulation and fibrinolysis | Factors regulating inflammatory process | ||||

|

Vasodilating effect |

Vasoconstricting effect |

Inhibition of proliferation |

Stimulation of proliferation |

Anticoagulant effect |

Prothrombotic effect |

Anti-inflammatory effect |

Proinflammatory effect |

| Adrenomedullin (ADM) | Angiotensin II (AT II) | Extracellular proteases inhibitors | Adenosine (Ado) | Antithrombin III (AT III) | ET-1 | NO | Adhesion molecules |

| Bradykinin (BK) | Endothelin-1 (ET-1) | NO | AT II | Heparan sulfate | PAF | PGI2 | Chemokines |

| C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) | Platelet-activating factor (PAF) | PGI2 | ET-1 | NO | Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) | Cytokines | |

| Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) | Prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) | Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) | Heparan sulfate | PGI2 | ROS | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) | |

| Nitric oxide (NO) | Thromboxane A2 (TXA2) | Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) | Protein C (PC) | Tissue factor (TF) | |||

| Prostacyclin (PGI2) | Reactive oxygen species (ROS) | Interleukins (Il) | Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) | TXA2 | |||

| ROS | Tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) | Von Willebrand factor (VWF) | |||||

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) | Urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) | ||||||

Figure 1.

Anticoagulant activity of endothelium. NO: Nitric oxide; PGI2: Prostacyclin; PC: Protein C; APC: Activated protein C; V, VIII: Coagulation factors; TFPI: Tissue factor pathway inhibitor; t-PA: Tissue-type plasminogen activator.

Figure 2.

Procoagulant activity of endothelium. PAI-1: Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1; t-PA: Tissue-type plasminogen activator; TXA2: Thromboxane A2; TF: Tissue factor; VWF: von Willebrand factor.

NO is a key mediator secreted by the endothelium and is produced from L-arginine by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)[8]. It is released from the endothelium in response to shearing forces applied to the vascular wall[9]. It acts by increasing the concentration of cyclic guanosine monophosphate, which has a vasodilatory effect, and also inhibits the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and leukocyte adhesion substances, inhibits blood platelet adhesion and aggregation, and limits the proliferation of smooth muscle cells in the vascular wall[6,9]. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor also has a vasodilatory effect, whereas a vasoconstrictive effect is exhibited by endothelin 1 and endothelium-derived contracting factor.

PATHOGENESIS

Vascular endothelium

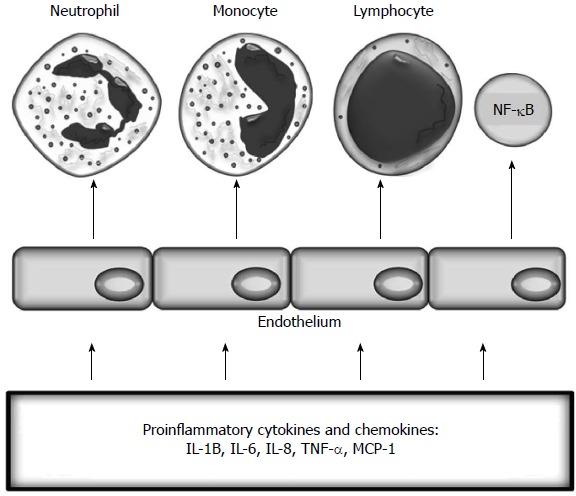

Endothelial dysfunction is “an imbalance between vasodilatating and vasoconstricting substances produced by (or acting on) endothelial cells”[10]. Inflammation leads to functional and structural changes in vascular endothelium and its activation (Figure 3). These changes initially include increased leukocyte adhesiveness, leukocyte diapedesis, and vascular smooth muscle tone and procoagulant activity[5,11]. Activation of endothelial cells is promoted by the interactions between integrins and chemokine receptors with endothelial and mucosal ligands, the CAM superfamily, and chemokines[12,13]. Activated endothelium expresses CAMs and chemokines, which promote the recruitment of leukocytes[14,15]. Adhesion is the most important process determining which leukocytes migrate to tissues[16]. The three main classes of CAMs are selectins, integrins, and the immunoglobulin CAM superfamily, including intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), ICAM-2, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1))[17]. This process is mainly mediated by leukocyte CD11a/CD18 binding to ICAM-1 in the gut or by α4-β1 or α4-β7 binding to VCAM-1 and mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1)[12].

Figure 3.

Inflammatory activation of endothelium. TNF: Tumour necrosis factor; IL: Interleukin.

Cultures of human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells (HIMECs) have revealed unique leukocyte adhesion and growth patterns[18]. Significant changes, particularly an enhanced capacity to adhere to leukocytes, occur in chronically inflamed microvessels of patients with IBD compared to vessels from healthy controls and patients without IBD[5]. Microvascular expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 is upregulated in patients with IBD[14,16]. Increased MAdCAM-1 expression is also observed, which increases recruitment of α4 integrin-expressing leukocytes[19]. Vowinkel et al[20] demonstrated a significant increase in endothelial expression of CD40, resulting in increased recruitment of leukocytes.

The risk for hyperhomocysteinemia is significantly higher in patients with IBD than in those without the disease[21,22]. HIMECs are activated by homocysteine alone or homocysteine combined with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), leading to enhanced VCAM-1 expression, increased production of monocyte chemotactic protein-1, and phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase[16,23].

Decreased NO production occurs in patients with IBD, which may be caused by increased arginase activity, an enzyme that competes with NOS, and a lack of inducible NOS mRNA expression[16,24,25]. Vascular endothelium is also a TNF-α target[11]. Binding of TNF-α to the TNF receptor leads to diminished eNOS protein expression and suppresses eNOS activity, which prevents degradation of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous eNOS inhibitor[11,26]. Reactive oxygen species are produced in the inflamed area, which generate oxidative stress in vWF molecules. This process inhibits cleavage of vWF molecules by disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motif-13 and contributes to the creation of ultra-large vWF multimers leading to microvascular thrombosis in patients with IBD[13,17,27].

Structural changes in vascular endothelium include capillary and venule remodeling and proliferation of endothelial cells[28]. Angiogenesis is a crucial process that sustains chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. Numerous inflammatory cell types, including macrophages, lymphocytes, mast cells, and fibroblasts, produce angiogenic factors and promote pathological angiogenesis in inflammatory tissues[16,29]. Hypoxia in the inflamed area stimulates angiogenesis by upregulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor, and TNF-α[29]. Rutella et al[30] suggested that inflamed HIMECs recruit platelets to produce higher levels of pro-angiogenic VEGF-A and CD40 ligand (CD40L) in patients with active ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD)[30].

The CD40-CD40L pathway has a dual role, directly stimulating mucosal angiogenesis and activating CD40L-expressing T cells, which in turn stimulates intestinal fibroblasts to release angiogenic cytokines[31]. CD40 is upregulated by several cell types in patients with IBD, including antigen-presenting cells, monocytes, and endothelial cells. CD40L is overexpressed by T cells and platelets, and plasma CD40L levels are particularly high in patients with active IBD[31,32]. The CD40-CD40L pathway promotes mucosal inflammation and triggers increased production of various cytokines and cell adhesion molecules[31]. CD40 binding stimulates the production of TNF-α, and TNF-α increases CD40 expression[32].

Intestinal endothelium is also involved in innate immunity by expressing toll-like receptors (TLRs), which increase the expression of proinflammatory genes and promote leukocyte chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and cytotoxicity as a second-line defense against bacterial entry[33]. Expression of TLRs on vascular endothelial cells is upregulated by vascular inflammation, as well as by lipopolysaccharide. Endothelial cells detect both extracellular and intracellular microbial invaders through TLRs and activate the nucleotide oligomerization domain family of proteins[34]. Activated TLRs upregulate endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecules, increasing leukocyte transmigration[35].

Tolstanova et al[36] demonstrated that damage to endothelium and increased vascular permeability lead to hypoxia in four UC animal models, which increases the levels of oxygen-derived toxic free radicals and induces epithelial cell injury followed by the development of erosions und ulcerations. Genetic predisposition, activation of the VEGF gene, and activation of TLR2 by oxidation stress are responsible for increased endothelial microvascular permeability in patients with UC[36].

Lymphatic endothelium

The lymphatic vessels are responsible for intestinal lymphatic transport and elimination of accumulated fluid, inflammatory cells, and mediators. However, inflammatory mediators released alter lymphatic vessel function and impair lymph flow in patients with IBD, which exacerbates tissue edema and the accumulation of dead cells and bacteria. Lymphangiogenesis is mediated by binding of the lymphatic vascular endothelial selective growth factors VEGF-C and VEGF-D/VEGF receptor-3[37].

Lymphatic obstruction, submucosal edema, and extended lymphangiogenesis are observed in patients with IBD[13,16]. Rahier et al[38] reported that lymphatic density increases significantly in patients with CD and UC in both inflamed and non-inflamed intestinal mucosa. Tonelli et al[39] demonstrated a correlation between parietal wall thickness and the severity of changes in lymphatic drainage in patients with IBD and stenosis, and reported that these abnormalities disappeared after strictureplasty. It remains unclear whether the impaired lymphatic function in patients with IBD is a consequence of inflammation or a preceding lymphangitis-like event[40].

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS OF DETECTING ENDOTHELIAL DYSFUNCTION

Endothelial dysfunction is diagnosed using physical and biochemical methods. Physical methods are based on assessing vasodilation in large arteries in response to increased flow and receptor stimulation, mainly acetylcholine[3,34]. The most popular non-invasive procedures are presented in Table 2. Among these methods, flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD) is the most widely used and the most sensitive[11,41]. However, these methods may not accurately reflect endothelial function in the microcirculation and are less sensitive for detecting early changes in endothelial function[11,42].

Table 2.

Methods of endothelium dysfunction assessment

| Proteins activated by normal and activated endothelium | Cell-based methods |

| Angiopoietin-1 | Circulating angiogenic cells |

| Angiopoietin-2 | Endothelial progenitor cells |

| Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) | Endothelial microparticles |

| Disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motif-13 (ADAMTS13) | |

| Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (CAM-1) | |

| Plasminogen-activator inhibitor (PAI-1) | |

| Selectins P and E | |

| Tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) | |

| Thrombomodulin | |

| Vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) | |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) | |

| von Willebrand factor (vWF) | |

| Non-invasive physical methods | |

| Carotis intima-media thickness (cIMT) | |

| Flow mediated dilatation (FMD) | |

| Pulse arterial tonometry (PAT) | |

| Pulse wave analysis (PWA) | |

| Pulse wave velocity (PWV) | |

| Reactive hyperaemia index (RHI) | |

The biochemical methods used to detect endothelial dysfunction are based on assessing the synthesis of compounds produced by normal and damaged endothelium. Numerous substances are released by abnormally activated endothelium (Table 2)[11,43].

Endothelial activity in patients with IBD has been evaluated by physical and biochemical methods. Kocaman et al[44] reported that both endothelial-dependent and endothelial-independent dilation are significantly worse in patients with severe or moderate UC than in controls, and that endothelial dysfunction is associated with activity-related extra-intestinal complications.

Roifman et al[42] assessed endothelial dysfunction and found that 48 patients with UC and CD had lower pulse arterial tonometry values and shear stress reactive hyperemia compared to controls, which indicates endothelial dysfunction. However, no association was detected between clinical features such as disease duration, underlying therapy, or disease activity. Theocharidou et al[45] reported that carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) increases significantly in patients with UC and CD but lacks an association with clinical disease activity. Similarly, Aloi et al[46] found an increase in cIMT and a decrease in FMD in pediatric patients. Zanoli et al[47] demonstrated that arterial stiffness increases in patients with IBD independently of conventional cardiovascular risk factors and that carotid-radial pulse wave velocity (PWV) is positively correlated with disease duration. Arterial stiffness decreases following immunomodulatory therapy (steroids and azathioprine or anti-TNF-α)[48]. Several studies have reported no differences in cIMT values in patients with IBD[49-52]. Ozturk et al[49] measured carotid femoral PWV, cIMT, and FMD in a group of patients with IBD without additional cardiovascular risks. They did not find any changes in cIMT, but they reported a significantly lower FMD and higher carotid femoral PWV. Similarly, a Korean study on 38 patients with IBD did not show an increase in cIMT compared to healthy controls. Disease severity was not correlated with cIMT but a positive correlation was detected with disease duration[50]. Kayahan et al[51] and Broide et al[52] reported no differences in cIMT, but the latter study reported a significantly impaired FMD in patients with IBD. Petr et al[53] evaluated the reactive hyperemia index (RHI) and E-selectin and ADMA levels in 21 patients with CD and reported a decrease in RHI but increases in E-selectin and ADMA levels.

A few studies have assessed the levels of endothelial dysfunction biomarkers in serum of patients with IBD and have provided controversial data. Some studies have reported an increase in VEGF level[54,55]. In another study, no difference in ICAM-1 or E-selectin expression was observed between patients with active UC and inactive CD[56]. In contrast, Adamska et al[57] reported a significant increase in E-selectin expression in patients with active CD compared to patients in remission. Similarly, Goggins et al[58] demonstrated an increase in levels of ICAM-1 and E-selectin in serum of patients with IBD but C-reactive protein (CRP) was a better indicator of disease activity. Another study found increased ICAM-1 levels in patients with IBD compared to healthy controls[55]. Magro et al[59] demonstrated that levels of P-selectin, E-selectin, VCAM, ICAM, VEGF, and angiogenin in serrum are significantly lower in patients with inactive CD than in controls, suggesting dysfunction in the angiogenic process and wound repair. Lower levels of VEGF and angiogenin have been demonstrated in patients with inactive IBD compared to those with active disease[60].

IMPLICATIONS

Risk of cardiovascular complications

Chronic systemic inflammatory diseases are associated with accelerated atherosclerosis, a higher rate of cardiovascular disease (CVD), and increased morbidity and mortality compared to the general population[11,61-63]. Inflammatory mediators, such as CRP, TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-18, and CD40L, are involved in the pathogenesis of inflammation and atherosclerosis[64,65]. Endothelial dysfunction is considered the initial step in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in the general population and may be a marker for future risk of cardiovascular events[66].

The risk for CVD in patients with IBD is controversial. Some studies have demonstrated an increased risk for CVD in these patients[66-68], whereas others have provided no evidence for an increased risk of mortality due to CVD[69-71]. Ruisi et al[72] found no increased risk for CVD in patients with IBD without traditional CVD risk factors after a 2-year follow-up. A meta-analysis performed by Fumery et al[73] and composed of 33 observational studies showed a higher risk for ischemic heart disease and arterial thromboembolism in patients with IBD but no increased risk for cardiovascular mortality. In addition, Singh et al[74] reported a 19% higher risk of CVD in patients with IBD and a modest increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity (from cerebrovascular accidents and ischemic heart disease), mostly in female patients[74]. Kristensen et al[75] performed a population-based study and demonstrated an increased risk for myocardial infarction in patients with IBD during flare-ups and during persistent disease activity, but not in patients in remission[76].

Coronary flow reserve is impaired in patients with IBD, suggesting dysfunction in coronary microcirculation[76].

Fan et al[77] concluded that traditional risk factors, such as age, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, diabetes, and triglycerides, rather than inflammatory markers, are major predictors of arterial stiffness in patients with an inflammatory disease. In contrast, Ozturk et al[49] suggested that patients with IBD without traditional cardiovascular risk factors have higher risks for endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis.

Some studies have suggested that patients with IBD, particularly those with CD, exhibit low levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)[78]. However, Sappati Biyyani et al[79] reported lower total cholesterol but higher LDL and lower high-density lipoprotein levels in patients with IBD in a large retrospective study. Changes in the lipid profile do not depend on disease activity[77]. Despite a lower incidence of traditional CVD risk factors in patients with IBD, these patients are diagnosed with coronary artery disease at a younger age[67,80]. It is important to emphasize that some patients with CD are tobacco smokers, which could also contribute to enhanced endothelial damage[81]. These findings indicate that large prospective studies are needed to determine the actual risks for CVD in patients with IBD.

Pharmacological interventions and endothelial function

Pharmacological agents directed against TNF-α-mediated inflammation may decrease the risk for endothelial dysfunction and CVD in patients with IBD. Some studies that have addressed rheumatoid arthritis have demonstrated decreased levels of endothelial dysfunction biomarkers in plasma after anti-TNF-α therapy[11]. Other studies have shown improved endothelium-dependent vasodilation in patients with inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, psoriasis, and IBD after initiating anti-TNF-α therapy[11,48,82]. However, whether this effect is permanent or transient remains controversial[11]. Arijs et al[83] demonstrated that inflammatory cells from the intestinal lamina propria disappear after an infliximab infusion and that previously upregulated cell adhesion molecules are restored. Some authors have suggested that anti-TNF-α antibodies inhibit angiogenesis in patients with IBD[84,85]. Danese et al[32] showed that anti-TNF-α downregulates the CD40/CD40L pathway.

The effects of TNF-α on the cardiovascular system could be both beneficial and harmful due to concentration-related differences in activation of different receptors[63,86].

Data regarding corticosteroids are controversial as well. However, a systematic review of studies that assessed steroid administration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis did not report any effects of steroid use on endothelial function[87].

At the same time, it is probable that methotrexate improves endothelial-dependent vasodilation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis[62]. A weekly low dose of methotrexate reduces disease-associated cardiovascular mortality. Thornton et al[88] suggested that methotrexate induces cytoprotective genes by activating adenosine monophosphate protein kinase-cyclic AMP response element binding protein signaling, which prevents CVD.

In vitro studies have indicated that cyclosporine induces increased activation of endothelial cells[89]. However, some evidence suggests that cyclosporine A inhibits angiogenesis targeting VEGF-A[84,90]. At the same time, azathioprine and its metabolite, 6-mercaptopurine, may play a protective role against the activation of endothelial cells[91].

New therapeutic options for patients with IBD include anti-adhesion molecules, such as vedolizumab, etrolizumab, and PF-00547659[92]. Vedolizumab targets α4-β7 integrins and blocks interactions between α4-β7 integrins and MAdCAM-1. Etrolizumab targets the β7 subunit, and PF-00547659 is a monoclonal antibody against MAdCAM-1[92]. Anti-chemokine receptor CCR 9 interferes with the activation of inflammatory cells in the intestine. Other medications, such as laquinimod and tofacitinib, reduce the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines[92].

As the lymphatic endothelium seems to play an adaptive role in the inflammation that occurs in patients with IBD, the inflammatory process may also be affected by stimulating lymphatic vessel functions, such as drainage and clearance of bacterial antigens, together with adaptive immunity[37]. D’Alessio et al[37] demonstrated that adenoviral induction of the prolymphangiogenic factor VEGF-C in two different animal models significantly prevents the development of acute and chronic colitis, which supports the potential use of lymphangiogenic growth factors as a novel therapeutic approach[37].

Improved endothelial function may also be achieved by increasing NO availability, as antioxidants affect the decrease in NO breakdown. Dietary components, such as vitamins C and E, have potential benefits on endothelial function and could prevent CVD[93]. Recent studies provide no evidence for a supportive role of vitamin D in endothelial function[94]. Ibrahim et al[95] showed that treatment with long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid decreases the expression of adhesion molecules in endothelial cells and has a potential anti-angiogenic role in animal models and in vitro.

CONCLUSION

Endothelial dysfunction plays a pivotal role in the development of IBD. Some immunomodulatory medications used to treat IBD affect endothelial function; however, large studies on the interactions between the gut microvasculature, cytokines, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules, inflammatory growth factors, and platelets are needed to create new therapeutic strategies for patients with IBD.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors do not declare any conflicts of interest.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: May 12, 2015

First decision: July 20, 2015

Article in press: November 30, 2015

P- Reviewer: Lakatos PL S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Jakubowski A, Zagórowicz E, Kraszewska E, Bartnik W. Rising hospitalization rates for inflammatory bowel disease in Poland. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2014;124:180–190. doi: 10.20452/pamw.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedersen J, Coskun M, Soendergaard C, Salem M, Nielsen OH. Inflammatory pathways of importance for management of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:64–77. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baszczuk A, Kopczyński Z, Thielemann A. [Endothelial dysfunction in patients with primary hypertension and hyperhomocysteinemia] Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2014;68:91–100. doi: 10.5604/17322693.1087521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marti CN, Gheorghiade M, Kalogeropoulos AP, Georgiopoulou VV, Quyyumi AA, Butler J. Endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1455–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deban L, Correale C, Vetrano S, Malesci A, Danese S. Multiple pathogenic roles of microvasculature in inflammatory bowel disease: a Jack of all trades. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1457–1466. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obonska K, Grabczewska Z, Fisz J. Ocena czynnosci srodblonka naczyniowego - gdzie jestesmy, dokad zmierzamy? Folia Cardiologica Excerpta. 2010;5:292–297. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Libby P, Aikawa M, Jain MK. Vascular endothelium and atherosclerosis. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006;(176 Pt 2):285–306. doi: 10.1007/3-540-36028-x_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radomski MW, Salas E. Nitric oxide--biological mediator, modulator and factor of injury: its role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1995;118 Suppl:S69–S80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadar S, Blann AD, Lip GY. Endothelial dysfunction: methods of assessment and application to hypertension. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:3591–3605. doi: 10.2174/1381612043382765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deanfield J, Donald A, Ferri C, Giannattasio C, Halcox J, Halligan S, Lerman A, Mancia G, Oliver JJ, Pessina AC, et al. Endothelial function and dysfunction. Part I: Methodological issues for assessment in the different vascular beds: a statement by the Working Group on Endothelin and Endothelial Factors of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2005;23:7–17. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steyers CM, Miller FJ. Endothelial dysfunction in chronic inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:11324–11349. doi: 10.3390/ijms150711324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charo IF, Ransohoff RM. The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:610–621. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Alessio S, Tacconi C, Fiocchi C, Danese S. Advances in therapeutic interventions targeting the vascular and lymphatic endothelium in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:608–613. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328365d37c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatoum OA, Miura H, Binion DG. The vascular contribution in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1791–H1796. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00552.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danese S, Semeraro S, Marini M, Roberto I, Armuzzi A, Papa A, Gasbarrini A. Adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease: therapeutic implications for gut inflammation. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danese S. Role of the vascular and lymphatic endothelium in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease: ‘brothers in arms’. Gut. 2011;60:998–1008. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.207480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scaldaferri F, Lancellotti S, Pizzoferrato M, De Cristofaro R. Haemostatic system in inflammatory bowel diseases: new players in gut inflammation. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:594–608. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i5.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binion DG, West GA, Ina K, Ziats NP, Emancipator SN, Fiocchi C. Enhanced leukocyte binding by intestinal microvascular endothelial cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1895–1907. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briskin M, Winsor-Hines D, Shyjan A, Cochran N, Bloom S, Wilson J, McEvoy LM, Butcher EC, Kassam N, Mackay CR, et al. Human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is preferentially expressed in intestinal tract and associated lymphoid tissue. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:97–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vowinkel T, Anthoni C, Wood KC, Stokes KY, Russell J, Gray L, Bharwani S, Senninger N, Alexander JS, Krieglstein CF, et al. CD40-CD40 ligand mediates the recruitment of leukocytes and platelets in the inflamed murine colon. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:955–965. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keshteli AH, Baracos VE, Madsen KL. Hyperhomocysteinemia as a potential contributor of colorectal cancer development in inflammatory bowel diseases: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1081–1090. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i4.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owczarek D, Cibor D, Sałapa K, Jurczyszyn A, Mach T. Homocysteine in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Przegl Lek. 2014;71:189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danese S, Sgambato A, Papa A, Scaldaferri F, Pola R, Sans M, Lovecchio M, Gasbarrini G, Cittadini A, Gasbarrini A. Homocysteine triggers mucosal microvascular activation in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:886–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horowitz S, Binion DG, Nelson VM, Kanaa Y, Javadi P, Lazarova Z, Andrekopoulos C, Kalyanaraman B, Otterson MF, Rafiee P. Increased arginase activity and endothelial dysfunction in human inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1323–G1336. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00499.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magro F, Soares JB, Fernandes D. Venous thrombosis and prothrombotic factors in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4857–4872. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owczarek D, Cibor D, Mach T. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA), arginine, and 8-iso-prostaglandin F2alpha (8-iso-PGF2alpha) level in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:52–57. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lancellotti S, De Filippis V, Pozzi N, Peyvandi F, Palla R, Rocca B, Rutella S, Pitocco D, Mannucci PM, De Cristofaro R. Formation of methionine sulfoxide by peroxynitrite at position 1606 of von Willebrand factor inhibits its cleavage by ADAMTS-13: A new prothrombotic mechanism in diseases associated with oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:389–395. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koutroubakis IE, Tsiolakidou G, Karmiris K, Kouroumalis EA. Role of angiogenesis in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:515–523. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutella S, Vetrano S, Correale C, Graziani C, Sturm A, Spinelli A, De Cristofaro R, Repici A, Malesci A, Danese S. Enhanced platelet adhesion induces angiogenesis in intestinal inflammation and inflammatory bowel disease microvasculature. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danese S, Scaldaferri F, Vetrano S, Stefanelli T, Graziani C, Repici A, Ricci R, Straface G, Sgambato A, Malesci A, et al. Critical role of the CD40 CD40-ligand pathway in regulating mucosal inflammation-driven angiogenesis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2007;56:1248–1256. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.111989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danese S, Sans M, Scaldaferri F, Sgambato A, Rutella S, Cittadini A, Piqué JM, Panes J, Katz JA, Gasbarrini A, et al. TNF-alpha blockade down-regulates the CD40/CD40L pathway in the mucosal microcirculation: a novel anti-inflammatory mechanism of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. J Immunol. 2006;176:2617–2624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidemann J, Domschke W, Kucharzik T, Maaser C. Intestinal microvascular endothelium and innate immunity in inflammatory bowel disease: a second line of defense? Infect Immun. 2006;74:5425–5432. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00248-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faure E, Thomas L, Xu H, Medvedev A, Equils O, Arditi M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide and IFN-gamma induce Toll-like receptor 2 and Toll-like receptor 4 expression in human endothelial cells: role of NF-kappa B activation. J Immunol. 2001;166:2018–2024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tolstanova G, Deng X, French SW, Lungo W, Paunovic B, Khomenko T, Ahluwalia A, Kaplan T, Dacosta-Iyer M, Tarnawski A, et al. Early endothelial damage and increased colonic vascular permeability in the development of experimental ulcerative colitis in rats and mice. Lab Invest. 2012;92:9–21. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Alessio S, Correale C, Tacconi C, Gandelli A, Pietrogrande G, Vetrano S, Genua M, Arena V, Spinelli A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. VEGF-C-dependent stimulation of lymphatic function ameliorates experimental inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3863–3878. doi: 10.1172/JCI72189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahier JF, De Beauce S, Dubuquoy L, Erdual E, Colombel JF, Jouret-Mourin A, Geboes K, Desreumaux P. Increased lymphatic vessel density and lymphangiogenesis in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:533–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonelli F, Giudici F, Liscia G. Is lymphatic status related to regression of inflammation in Crohn’s disease? World J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;4:228–233. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i10.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Becker F, Yi P, Al-Kofahi M, Ganta VC, Morris J, Alexander JS. Lymphatic dysregulation in intestinal inflammation: new insights into inflammatory bowel disease pathomechanisms. Lymphology. 2014;47:3–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilk G, Osmenda G, Matusik P, Nowakowski D, Jasiewicz-Honkisz B, Ignacak A, Cześnikiewicz-Guzik M, Guzik TJ. Endothelial function assessment in atherosclerosis: comparison of brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilation and peripheral arterial tonometry. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:443–452. doi: 10.20452/pamw.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roifman I, Sun YC, Fedwick JP, Panaccione R, Buret AG, Liu H, Rostom A, Anderson TJ, Beck PL. Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Page AV, Liles WC. Biomarkers of endothelial activation/dysfunction in infectious diseases. Virulence. 2013;4:507–516. doi: 10.4161/viru.24530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kocaman O, Sahin T, Aygun C, Senturk O, Hulagu S. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:166–171. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000217764.88980.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Theocharidou E, Gossios TD, Griva T, Giouleme O, Douma S, Athyros VG, Karagiannis A. Is there an association between inflammatory bowel diseases and carotid intima-media thickness? Preliminary data. Angiology. 2014;65:543–550. doi: 10.1177/0003319713489876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aloi M, Tromba L, Di Nardo G, Dilillo A, Del Giudice E, Marocchi E, Viola F, Civitelli F, Berni A, Cucchiara S. Premature subclinical atherosclerosis in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr. 2012;161:589–594.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zanoli L, Cannavò M, Rastelli S, Di Pino L, Monte I, Di Gangi M, Boutouyrie P, Inserra G, Laurent S, Castellino P. Arterial stiffness is increased in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1775–1781. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283568abd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zanoli L, Rastelli S, Inserra G, Lentini P, Valvo E, Calcagno E, Boutouyrie P, Laurent S, Castellino P. Increased arterial stiffness in inflammatory bowel diseases is dependent upon inflammation and reduced by immunomodulatory drugs. Atherosclerosis. 2014;234:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozturk K, Guler AK, Cakir M, Ozen A, Demirci H, Turker T, Demirbas S, Uygun A, Gulsen M, Bagci S. Pulse Wave Velocity, Intima Media Thickness, and Flow-mediated Dilatation in Patients with Normotensive Normoglycemic Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1314–1320. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim KO, Jang BI, Lee SH. Does carotid intima-media thickness increase in patients with inflammatory bowel disease? Intest Res. 2014;12:293–298. doi: 10.5217/ir.2014.12.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kayahan H, Sari I, Cullu N, Yuksel F, Demir S, Akarsu M, Goktay Y, Unsal B, Akpinar H. Evaluation of early atherosclerosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2137–2143. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Broide E, Schopan A, Zaretsky M, Kimchi NA, Shapiro M, Scapa E. Intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery is not significantly higher in Crohn’s disease patients compared to healthy population. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:197–202. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petr J, Michal H, Jan S, Ladislav T, Jiri K, Josef S. Reactive hyperaemia index as a marker of endothelial dysfunction in children with Crohn’s disease is significantly lower than healthy controls. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103:e55–e60. doi: 10.1111/apa.12467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Sabatino A, Ciccocioppo R, Armellini E, Morera R, Ricevuti L, Cazzola P, Fulle I, Corazza GR. Serum bFGF and VEGF correlate respectively with bowel wall thickness and intramural blood flow in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:573–577. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song WB, Lv YH, Zhang ZS, Li YN, Xiao LP, Yu XP, Wang YY, Ji HL, Ma L. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1, D-lactate and diamine oxidase in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3916–3919. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones SC, Banks RE, Haidar A, Gearing AJ, Hemingway IK, Ibbotson SH, Dixon MF, Axon AT. Adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1995;36:724–730. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adamska I, Czerwionka-Szaflarska M, Kulwas A, Mierzwa G, Bała G, Rość D. [Value of E-selectin and L-selectin determination in children and youth with inflammatory bowel disease] Med Wieku Rozwoj. 2007;11:413–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goggins MG, Goh J, O’Connell MA, Weir DG, Kelleher D, Mahmud N. Soluble adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Ir J Med Sci. 2001;170:107–111. doi: 10.1007/BF03168821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magro F, Araujo F, Pereira P, Meireles E, Diniz-Ribeiro M, Velosom FT. Soluble selectins, sICAM, sVCAM, and angiogenic proteins in different activity groups of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1265–1274. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000037822.55717.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Algaba A, Linares PM, Fernández-Contreras ME, Ordoñez A, Trápaga J, Guerra I, Chaparro M, de la Poza G, Gisbert JP, Bermejo F. Relationship between levels of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors and the endoscopic, histological and clinical activity, and acute-phase reactants in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e569–e579. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murdaca G, Colombo BM, Cagnati P, Gulli R, Spanò F, Puppo F. Endothelial dysfunction in rheumatic autoimmune diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2012;224:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prati C, Demougeot C, Guillot X, Godfrin-Valnet M, Wendling D. Endothelial dysfunction in joint disease. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Andersen NN, Jess T. Risk of cardiovascular disease in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5:359–365. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hatoum OA, Binion DG. The vasculature and inflammatory bowel disease: contribution to pathogenesis and clinical pathology. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:304–313. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000160772.78951.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaptoge S, Seshasai SR, Gao P, Freitag DF, Butterworth AS, Borglykke A, Di Angelantonio E, Gudnason V, Rumley A, Lowe GD, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and risk of coronary heart disease: new prospective study and updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:578–589. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109:III27–III32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131515.03336.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yarur AJ, Deshpande AR, Pechman DM, Tamariz L, Abreu MT, Sussman DA. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:741–747. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rungoe C, Basit S, Ranthe MF, Wohlfahrt J, Langholz E, Jess T. Risk of ischaemic heart disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Gut. 2013;62:689–694. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dorn SD, Sandler RS. Inflammatory bowel disease is not a risk factor for cardiovascular disease mortality: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:662–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jess T, Gamborg M, Munkholm P, Sørensen TI. Overall and cause-specific mortality in ulcerative colitis: meta-analysis of population-based inception cohort studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:609–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bewtra M, Kaiser LM, TenHave T, Lewis JD. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are associated with elevated standardized mortality ratios: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:599–613. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31827f27ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ruisi P, Makaryus JN, Ruisi M, Makaryus AN. Inflammatory bowel disease as a risk factor for premature coronary artery disease. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7:257–261. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2102w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fumery M, Xiaocang C, Dauchet L, Gower-Rousseau C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Thromboembolic events and cardiovascular mortality in inflammatory bowel diseases: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh S, Singh H, Loftus EV, Pardi DS. Risk of cerebrovascular accidents and ischemic heart disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:382–393.e1: quiz e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kristensen SL, Ahlehoff O, Lindhardsen J, Erichsen R, Jensen GV, Torp-Pedersen C, Nielsen OH, Gislason GH, Hansen PR. Disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease is associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death--a Danish nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Caliskan Z, Gokturk HS, Caliskan M, Gullu H, Ciftci O, Ozgur GT, Guven A, Selcuk H. Impaired coronary microvascular and left ventricular diastolic function in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Microvasc Res. 2015;97:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fan F, Galvin A, Fang L, White DA, Moore XL, Sparrow M, Cicuttini F, Dart AM. Comparison of inflammation, arterial stiffness and traditional cardiovascular risk factors between rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. J Inflamm (Lond) 2014;11:29. doi: 10.1186/s12950-014-0029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Agouridis AP, Elisaf M, Milionis HJ. An overview of lipid abnormalities in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2011;24:181–187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sappati Biyyani RS, Putka BS, Mullen KD. Dyslipidemia and lipoprotein profiles in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Lipidol. 2010;4:478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aggarwal A, Atreja A, Kapadia S, Lopez R, Achkar JP. Conventional risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease with confirmed coronary artery disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1593–1601. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Szpak D, Grochowalski A, Chrząszcz R, Florek E, Jawień W, Undas A. Tobacco smoke exposure and endothelial dysfunction in patients with advanced coronary artery disease. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:474–481. doi: 10.20452/pamw.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schinzari F, Armuzzi A, De Pascalis B, Mores N, Tesauro M, Melina D, Cardillo C. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonism improves endothelial dysfunction in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:70–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arijs I, De Hertogh G, Machiels K, Van Steen K, Lemaire K, Schraenen A, Van Lommel L, Quintens R, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, et al. Mucosal gene expression of cell adhesion molecules, chemokines, and chemokine receptors in patients with inflammatory bowel disease before and after infliximab treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:748–761. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cromer WE, Mathis JM, Granger DN, Chaitanya GV, Alexander JS. Role of the endothelium in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:578–593. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i5.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scaldaferri F, Vetrano S, Sans M, Arena V, Straface G, Stigliano E, Repici A, Sturm A, Malesci A, Panes J, et al. VEGF-A links angiogenesis and inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:585–595.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Padfield GJ, Din JN, Koushiappi E, Mills NL, Robinson SD, Cruden Nle M, Lucking AJ, Chia S, Harding SA, Newby DE. Cardiovascular effects of tumour necrosis factor α antagonism in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a first in human study. Heart. 2013;99:1330–1335. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ruyssen-Witrand A, Fautrel B, Saraux A, Le Loët X, Pham T. Cardiovascular risk induced by low-dose corticosteroids in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thornton CC, Al-Rashed F, Calay D, Birdsey GM, Bauer A, Mylroie H, Morley BJ, Randi AM, Haskard DO, Boyle JJ, et al. Methotrexate-mediated activation of an AMPK-CREB-dependent pathway: a novel mechanism for vascular protection in chronic systemic inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bombeli T, Müller M, Straub PW, Haeberli A. Cyclosporine-induced detachment of vascular endothelial cells initiates the intrinsic coagulation system in plasma and whole blood. J Lab Clin Med. 1996;127:621–634. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(96)90153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rafiee P, Heidemann J, Ogawa H, Johnson NA, Fisher PJ, Li MS, Otterson MF, Johnson CP, Binion DG. Cyclosporin A differentially inhibits multiple steps in VEGF induced angiogenesis in human microvascular endothelial cells through altered intracellular signaling. Cell Commun Signal. 2004;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marinković G, Kroon J, Hoogenboezem M, Hoeben KA, Ruiter MS, Kurakula K, Otermin Rubio I, Vos M, de Vries CJ, van Buul JD, et al. Inhibition of GTPase Rac1 in endothelium by 6-mercaptopurine results in immunosuppression in nonimmune cells: new target for an old drug. J Immunol. 2014;192:4370–4378. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Löwenberg M, D’Haens G. Next-Generation Therapeutics for IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:21. doi: 10.1007/s11894-015-0444-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bruyndonckx L, Hoymans VY, Van Craenenbroeck AH, Vissers DK, Vrints CJ, Ramet J, Conraads VM. Assessment of endothelial dysfunction in childhood obesity and clinical use. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:174782. doi: 10.1155/2013/174782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alyami A, Soares MJ, Sherriff JL, Mamo JC. Vitamin D & amp; endothelial function. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:483–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ibrahim A, Mbodji K, Hassan A, Aziz M, Boukhettala N, Coëffier M, Savoye G, Déchelotte P, Marion-Letellier R. Anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic effect of long chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in intestinal microvascular endothelium. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:678–687. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]