Abstract

Objective

To study temporal trends of mortality in HIV-infected adults who attended an HIV clinic in Kampala, Uganda, between 2002 and 2012.

Design

Descriptive retrospective study.

Methods

Two doctors independently reviewed the clinic database that contained information derived from the clinic files and assigned one or more causes of death to each patient >18 years of age with a known date of death. Four cause-of-death categories were defined: ‘communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies’, ‘chronic non-communicable conditions’, ‘other non-communicable conditions’ and ‘unknown’. Trends in cause-of-death categories over time were evaluated using multinomial logistic regression with year of death as an independent continuous variable.

Results

1028 deaths were included; 38% of these individuals were on antiretroviral therapy (ART). The estimated mortality rate dropped from 21.86 deaths/100 person years of follow-up (PYFU) in 2002 to 1.75/100 PYFU in 2012. There was a significant change in causes of death over time (p<0.01). Between 2002 and 2012, the proportion of deaths due to ‘communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies’ decreased from 84% (95% CI 74% to 90%) to 64% (95% CI 53% to 74%) and the proportion of deaths due to ‘chronic non-communicable conditions’, ‘other non-communicable conditions’ and a combination of ‘communicable and non-communicable conditions’ increased. Tuberculosis (TB) was the main cause of death (34%). Death from TB decreased over time, from 43% (95% CI 32% to 53%) in 2002 to a steady proportion of approximately 25% from 2006 onwards (p<0.01).

Conclusions

Mortality rate decreased over time. The proportion of deaths from communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies decreased and from non-communicable diseases, both chronic and non-chronic, increased. Nevertheless, communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies continued to cause the majority of deaths, with TB as the main cause. Ongoing monitoring of cause of death is warranted and strategies to decrease mortality from TB and other common opportunistic infections are essential.

Keywords: INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is one of the few studies reporting on temporal trends in causes of death of HIV-infected adults in sub-Saharan Africa and reporting causes of death in individuals on antiretroviral treatment for longer than 1 year.

The study clinic has an elaborate network of care provision that involves community healthcare workers who frequently make home visits and make notes in the clinic file. Therefore, despite the retrospective nature of the study, the occurrence of a death and a probable cause of death could be assessed in most cases.

The lack of data on the whole clinic population forced us to estimate the mortality rate and prevented us from relating the changes observed in our cohort of deaths to changes in the clinic population.

Chart review is known to have a relatively poor accuracy in HIV-infected individuals when compared with the gold standard of complete histological autopsy. This is a common problem of all studies that use chart review to establish the cause of death. Since autopsies are not widely available, innovative and accurate alternatives are needed.

Background

Over the past decade, the landscape of HIV care and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has changed tremendously. Testing and counselling services have been scaled up, antiretroviral therapy (ART) has become more widely available and guidelines suggesting initiating ART at higher CD4 counts have been issued.1 2 In Uganda, the number of HIV-infected people on ART between 2001 and 2012 increased from scarcely any to almost 440 000.2 Moreover, improved diagnostic tests for common opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis (TB) are being implemented.3 4 All of these measures have resulted in a decline in mortality among HIV-infected individuals throughout SSA.2 5–7

In reports to date, the majority of deaths among HIV-infected adults in SSA have been secondary to HIV-related infections and malignancies.8 9 These studies included mainly untreated HIV-infected patients or patients recently started on ART. Studies including patients on ART for more than 1 year have been scarce. With the longer survival of HIV-infected individuals, one may expect a transition in causes of morbidity and mortality.10 Changes in socioeconomic development, lifestyle and dietary intake impact the causes of death in the population as a whole, and also that of HIV-infected individuals.11 ART-related toxicity and (low-level) chronic inflammation are additional factors that may influence the cause of death of HIV-infected patients. All of these factors can induce a shift towards causes of death that are not directly related to the immunodeficiency caused by HIV. In countries where ART has been available for a longer time, such a shift is already seen and hepatic diseases, cardiovascular diseases and non-AIDS malignancies have become common causes of death.12–14 Awareness of such a changing pattern in the African setting is of importance for patient care and resource allocation. Current HIV care in SSA is largely focused on management of opportunistic co-infections. If non-infectious chronic medical conditions become increasingly responsible for death among HIV-infected individuals, a shift in focus would be needed.15

We evaluated all-cause mortality in HIV-infected adults who attended an urban HIV treatment facility in Kampala, Uganda. We retrospectively studied the antemortem characteristics, the clinical course of the deceased and the causes of death since the start of the clinic in 2001 until 2012 to see if any temporal trends in causes of death could be observed. Moreover, we report the causes of death of patients on ART for more than 1 year.

Methods

Study setting and population

We conducted a retrospective study at the Reach Out Mbuya Parish HIV/AIDS Initiative (ROM) in Kampala. ROM's HIV treatment programme has been described in detail previously.16 17 In brief, ROM has provided free individual support services and community programmes to HIV-infected patients living in the urban slums that surround the parish since May 2001. Free ART first became available in June 2003 through research-based clinics and individual sponsorships. In March 2004, ROM was the first programme to initiate ART through the United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. However, the demand was greater than the supply and ART initiation was based on the principle to serve those with the lowest CD4 cell count first. ART eligibility was based on the WHO guidelines adopted for use through the Uganda National ART guidelines and subsequently followed the evolving recommendations to initiate ART at a higher CD4 cell count.

CD4 count measurement has been available since 2004, but viral load measurement was never routinely available. Nurse clinicians provide most of the clinic care. They are trained to work according to the national guidelines and can request for additional testing when indicated. They consult or refer to the medical officer when needed. Patients visit the clinic at intervals from every 2 weeks to once per 3 months depending on their treatment status. Moreover, community healthcare workers (CHWs), trained peers who support each patient and maintain a close relation with the patient, conduct home visits at intervals from daily to once per 3 months based on the needs of the specific patient. Bedridden or hospitalised patients are visited weekly by CHWs. Any relevant medical information obtained during their visits is noted in the clinic file.

Registration and tracing of patients

In the clinic registration system, patients are classified as ‘active’, ‘dead’, ‘lost to follow-up (LTFU)’ or ‘transferred out’. In case a patient misses the appointment, the CHW makes a home visit to ascertain the reason for the missed appointment. Until October 2008, missed appointments were identified using a handwritten register and it could take up to 1 month after the missed appointment that a CHW visit was made. Since then, an electronic medical record system has been installed that identifies missed appointments the same day and allows for home visits by the CHW within 24 h. A patient is classified as ‘dead’ if the clinic or CHW is informed about the patient’s death. If a patient misses clinic appointments for >90 days, the CHW is unable to gather additional information, he/she is classified as ‘LTFU’. Owing to the efficient community network and the frequent home visits, the clinic is generally well informed about the health status of its patients and reliable information about the circumstances of a death can be collected.

Mortality audit

In March 2013, ROM established a database including all patients who had died since the start of the clinic in May 2001. A trained administrative assistant extracted the following information from the clinic file of each patient known to have died: date of HIV diagnosis; date of registration; CD4 count at registration, at its lowest value, and the latest CD4 prior to death; if the patient was started on ART, the date ART was started and the regimen; the date of death; and the last weight and the height recorded prior to death. Two experienced medical doctors (LE and DK) then reviewed the clinic file and summarised the clinically relevant events preceding the death. In case of any inconsistency in the database, these doctors would review the patients’ clinic file and adjust the information accordingly.

Assigning the cause of death

Two study team doctors (DK and JAC) independently reviewed the database. A cause of death was assigned to each adult patient based on a listing of predefined causes of death, which was derived from the global burden of disease listing.18 Patients below 18 years of age or with an unknown death date were excluded. When no specific cause of death could be assigned, but the cause of death was considered to be related to a communicable disease, for example, because of the presence of fever, the category ‘communicable disease unspecified’ was assigned, and the organ system involved (respiratory, central nervous system, gastrointestinal, other or unclear) indicated. This was the same for ‘non-communicable diseases unspecified’. HIV as a cause of death was assigned only to patients with a CD4 count below 100 cells/mm3 in the 6 months preceding death without the start of ART and no apparent other cause of death. Two causes of death could be assigned to one patient if two diseases were thought to have contributed equally to a patient's death (eg, pulmonary TB and diabetic ketoacidosis). In cases where no distinction could be made between a communicable or non-communicable cause of death, the category ‘unknown’ was assigned. The cause-of-death listings of both doctors were compared, and in case of a discrepancy, it was discussed with a third doctor (RC) to assign a final consensus cause of death.

Outcomes and statistical methods

Causes of death were divided into four categories: (1) communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies, (2) chronic non-communicable conditions, (3) other non-communicable conditions which included pregnancy-related death, external causes (accidents, suicide, assault) and postoperative death and (4) unknown.

Proportions are reported with a Wilson 95% CI and medians with an IQR. When reporting CD4 counts, unless otherwise indicated, only results that were obtained within 6 months of the outcome of interest were included. For comparison of non-normally distributed variables, two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed. A p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Person years of follow-up (PYFU) for the whole clinic population were not available, but were estimated as follows: each patient in care on 31 December of the previous year was calculated as 1 PYFU, all new registrations during the year were calculated as 0.5 PYFU and all deaths during the year were calculated as 0.5 PYFU. For example, for 2003 we calculated 525 PYFU+0.5(860−525)+0.5×126=756 PYFU in total. We evaluated trends in the proportion of cause-of-death categories over time by using multinomial logistic regression with year of death as a continuous independent variable. We evaluated trends in individual diseases over time by using logistic regression with year of death as a continuous independent variable. Each individual disease was tested separately against the total of all other categories.

Results

On 1 May 2001, ROM started with 10 HIV-infected patients. By 31 December 2012, 4784 patients were in active care, of whom 92% were ≥18 years. In total, 1249 patients were classified ‘dead’ over the years, and of these, 1128 (90%) clinic files were retrieved and entered into the database. None of the files from the 20 deaths that occurred in 2001 were retrievable. Therefore, our study period covers 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2012.

After reviewing the database, the study team excluded 100 deaths from further analysis because they were aged <18 years (n=43) or their date of death was unknown (n=57). Hence, we analysed the data of 1028 deaths. At least one CD4 count was available for 68% of patients who died after 2004.

Characteristics of the deceased study participants

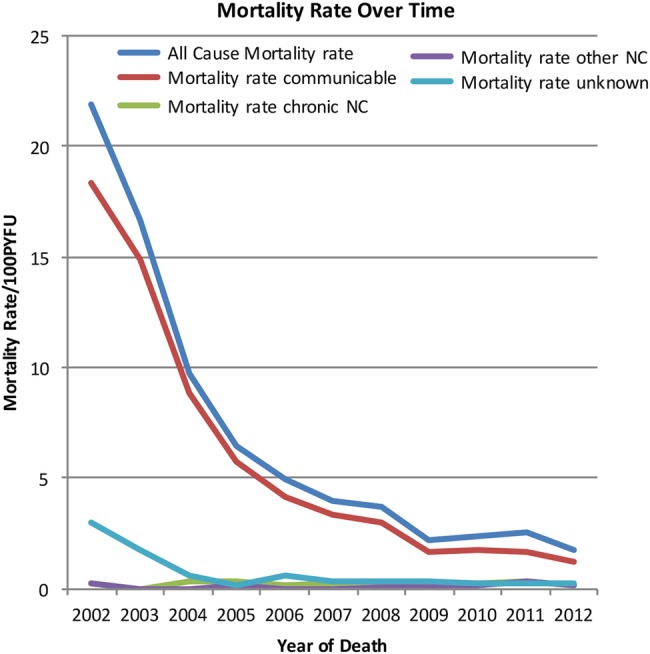

Over time, the estimated mortality rate dropped from 21.86 deaths/100 PYFU in 2002 to 1.75/100 PYFU in 2012. The mortality rate dropped mainly in the category ‘communicable condition and/or AIDS-defining malignancy’, from 18.3/100 PYFU in 2002 to 1.18/100 PYFU in 2012 (table 1 and figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the deceased patients per death year

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults in active care* | 525 | 860 | 1452 | 1892 | 2178 | 2724† | 2590 | 3250† | 3403 | 3557 | 4353 | – |

| Included deaths | 80 | 126 | 118 | 111 | 103 | 95 | 97 | 62 | 76 | 90 | 70 | 1028 |

| Estimated PYFU | 366 | 756 | 1215 | 1728 | 2087 | 2409 | 2616 | 2807 | 3221 | 3525 | 3990 | – |

| Mortality rate/100 PYFU | 21.86 | 16.67 | 9.71 | 6.42 | 4.94 | 3.94 | 3.71 | 2.21 | 2.36 | 2.55 | 1.75 | – |

| Median age (IQR) | 32 (28–37) | 35 (30–40) | 34 (29–42) | 36 (30–44) | 36 (29–42) | 38 (32–45) | 36 (30–41) | 36 (30–41) | 36 (28–45) | 39 (30–45) | 39 (31–45) | 36 (30–42) |

| Females n (%) | 53 (66) | 82 (65) | 69 (58) | 72 (65) | 64 (62) | 53 (56) | 51 (53) | 40 (65) | 38 (50) | 41 (46) | 34 (49) | 597 (58) |

| Median weight in kg (IQR) | 50 (42–56) | 50 (44–57) | 49 (43–55) | 49 (43–55) | 50 (44–56) | 50 (42–55) | 52 (45–60) | 49 (44–55) | 50 (44–56) | 54 (45–62) | 52 (45–60) | 51 (44–57) |

| Median BMI (IQR) | – | – | – | – | –‡ | 18.0 (16.1–20.1) | 18.8 (16.9–22.0) | 19.0 (17.6–21.6) | 18.5 (16.6–21) | 19.7 (17.6–21.8) | 18.8 (17.1–21.0) | 18.9 (17–21.6) |

| Median duration from registration to death (IQR)§ | 90 (53–203) | 162 (89–307) | 155 (80–291) | 170 (62–448) | 144 (58–393) | 128 (41–430) | 167 (67–789) | 271 (68–1193) | 170 (53–712) | 176 (59–1758) | 186 (61–774) | 158 (61–420) |

| Median CD4 at registration (IQR) | –‡ | –‡ | 49 (12–129) n=87 | 90 (25–232) n=98 | 127 (22–253) n=85 | 144 (34–304) n=73 | 119 (33–335) n=79 | 171 (60–390) n=54 | 100 (18–290) n=69 | 124 (35–268) n=83 | 81 (26–285) n=67 | 105 (25–265) n=70 |

| Median CD4 in 6 months prior to death (IQR) | –‡ | –‡ | 49 (12–121) n=73 | 74 (16–202) n=80 | 56 (22–207) n=61 | 93 (17–191) n=54 | 130 (36–275) n=64 | 132 (47–351) n=45 | 93 (13–245) n=53 | 180 (35–290) n=71 | 105 (27–290) n=55 | 90 (22–237) n=563 |

| On ART n (%) | – | 9 (7) | 48 (41) | 45 (41) | 45 (44) | 37 (39) | 44 (45) | 31 (50) | 38 (50) | 55 (61) | 43 (61) | 395 (38) |

| Median duration start ART—death (IQR)§ | – | 31 (18–33) | 61 (37–119) | 86 (42–312) | 142 (43–279) | 93 (43–392) | 144 (49–843) | 212 (39–1077) | 201 (44–1109) | 722 (77–1501) | 474 (104–1118) | 142 (47–555) |

| Start ART <3 month n (%) | – | 8 (89) | 34 (71) | 24 (53) | 17 (38) | 18 (49) | 17 (39) | 11 (35) | 11 (29) | 16 (29) | 8 (19) | 164 (42) |

| Start ART <6 month n (%) | – | 9 (100) | 42 (88) | 26 (58) | 29 (64) | 24 (65) | 23 (52) | 13 (42) | 19 (50) | 20 (36) | 15 (35) | 220 (56) |

| Start ART>12 month n (%) | – | – | – | 7 (16) | 10 (22) | 10 (27) | 16 (36) | 14 (45) | 14 (37) | 33 (60) | 23 (53) | 127 (32) |

*On 31 December of each year.

†Including children.

‡<7 Observations.

§Duration in days.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; BMI, body mass index; n, absolute number; PYFU, person years of follow-up.

Figure 1.

Estimated mortality rates per category per death year PYFU (NC, non-communicable condition; PYFU, person years of follow-up).

The median age at registration of all deceased was 36 years (IQR 30–42), 58% were female, the median duration between registration and death was 158 days (IQR 61–420), and 35% of all deaths occurred within 3 months after registration and 54% within 6 months (table 1). The median CD4 count prior to death was 90 cells/mm3 (IQR 22–237). Thirty-eight per cent (n=395) of deceased were on ART, and of these 42% died within the first 3 months of ART, 56% in the first 6 months and 68% within the first year. The median CD4 count in the 6 months prior to death stratified by year of death increased from 49 cells/mm3 in 2004 to 132 cells/mm3 in 2009. After 2010, it varied between 93 and 180 cells/mm3 (table 1). The proportion of deceased patients on ART steadily increased from 41% in 2004 to 61% in 2012. The median duration between the start of ART and death was 61 days (IQR 37–119) in 2004, then increased to a maximum of 722 days (IQR 77–1501) in 2011 and decreased again to 474 days (IQR 104–1118) in 2012.

Causes of death over time

Of the 1028 deceased, 784 (76%, 95% CI 74% to 79%) died of a ‘communicable condition or AIDS-defining malignancy’, 48 (5%, 95% CI 4% to 7%) of a ‘chronic non-communicable condition’ and 29 (3%, 95% CI 2% to 4%) of an ‘other non-communicable condition’. The remaining patients died of two ‘communicable conditions and/or AIDS-defining malignancies’ (n=47; 5%, 95% CI 3% to 6%) or a combination including at least one ‘communicable condition or AIDS-defining malignancy’ and one ‘chronic non-communicable condition’ (n=17; 2%, 95% CI 1% to 3%). For 103 patients (11%, 95% CI 9% to 13%), no cause of death could be determined.

Over time, the causes of death changed significantly (p<0.01). The proportion of deaths from communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies decreased, from 84% (95% CI 74% to 90%) in 2002 to 64% (95% CI 53% to 74%) in 2012. All other categories increased over time: death from chronic non-communicable conditions increased from 1% (95% CI 0% to 7%) in 2002 to 7% (95% CI 3% to 16%) in 2012, death from other non-communicable conditions from 1% (95% CI 0% to 7%) in 2002 to 7% (95% CI 3% to 16%) in 2012, death from a combination of communicable and non-communicable conditions from 0% in 2002 to 6% (95% CI 2% to 14%) in 2012 and death from an unknown cause from 1% (95% CI 0% to 7%) in 2002 to 6% (95% CI 2% to 14%) (table 2 and figure 2).

Table 2.

Causes of death per death year

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Communicable | ||||||||||||

| HIV | – | – | 6 (5) | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 5 (8) | 3 (4) | 4 (4) | 4 (6) | 35 (3) |

| Tuberculosis | 34 (43) | 68 (54) | 46 (39) | 37 (33) | 26 (25) | 26 (27) | 33 (34) | 15 (24) | 19 (25) | 24 (27) | 19 (27) | 347 (34) |

| Diarrhoeal disease | 2 (3) | 4 (3) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | – | 24 (2) |

| Respiratory tract infection | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 7 (1) |

| Meningitis | – | 6 (5) | 8 (7) | 6 (5) | 9 (9) | 8 (8) | 5 (5) | 4 (6) | 2 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 52 (5)* |

| Malaria | 1 (1) | – | – | – | – | 2 (2) | – | – | 3 (4) | 3 (3) | – | 9 (1) |

| Kaposi's sarcoma | 3 (4) | 8 (6) | 9 (8) | 10 (9) | 3 (3) | 10 (11) | 9 (9) | 3 (5) | 2 (3) | 5 (6) | – | 62 (6) |

| Other AIDS malignancy | – | – | – | – | 1 (1) | – | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | – | – | 1 (1) | 4 (<0.5) |

| Infection n.s. | 14 (18) | 12 (10) | 23 (19) | 19 (17) | 18 (17) | 19 (10) | 18 (19) | 9 (15) | 12 (16) | 12 (13) | 13 (19) | 169 (16) |

| Infection with respiratory symptoms | 7 (9) | 10 (8) | 13 (11) | 15 (14) | 10 (10) | 12 (13) | 9 (9) | 5 (8) | 6 (8) | 5 (6) | 3 (4) | 95 (9) |

| Infection with CNS symptoms | 4 (5) | 11 (9) | 8 (7) | 5 (5) | 8 (8) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (5) | 4 (5) | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | 53 (5) |

| Infection with GI symptoms | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | – | 2 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | 24 (2) |

| Other communicable specified | 1 (1) | – | – | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 15 (1) |

| Chronic NC | ||||||||||||

| Non-AIDS-defining malignancy | – | – | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 6 (7) | 1 (1) | 17 (2)† |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1 (1) | – | – | 1 (1) | – | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 12 (1) |

| Cerebrovascular event | – | – | – | 2 (2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (1) | 3 (<0.5) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | – | – | – | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 (<0.5) |

| GI and hepatic disease | – | – | – | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 4 (5) | 1 (1) | – | 11 (1)‡ |

| Neurological or psychiatric disorder | – | – | 1 (1) | – | – | – | 1 (1) | – | – | – | 1 (1) | 3 (<0.5) |

| Diabetes | – | – | 1 (1) | – | – | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | – | 3 (4) | 8 (1) |

| Chronic renal disease | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 4 (<0.5) |

| Chronic alcohol abuse | – | – | 1 (1) | – | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | – | – | – | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 5 (<0.5) |

| Other NC | ||||||||||||

| Pregnancy-related condition | – | – | – | 1 (1) | – | – | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | – | – | 1 (1) | 4 (<0.5) |

| Accidents, suicide, assault | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (1) | – | 3 (4) | 10 (11) | 2 (3) | 16 (2) |

| Postoperative death | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 (2) | – | 2 (<0.5) |

| Pulmonary embolus | 1 (1) | – | – | 1 (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 (<0.5) |

| Other condition n.s. | – | – | – | 1 (1) | – | – | – | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | – | 2 (3) | 5 (<0.5) |

*Confirmed cryptococcal meningitis caused death in 2% (n=24). †Consisting of malignancies of the oesophagus (n=5), breast (n=4), liver (n=1), larynx (n=1), sarcoma (n=1), brain (n=1), unknown primary origin (n=3). ‡Consisting of liver failure (n=8), upper GI bleed (n=2), cholangitis (n=1), pancreatitis (n=1).

CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; NC, non-communicable condition; n.s., non-specified.

Figure 2.

Cause of death per category per death year. *Patients who died from a combination of ‘communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies’ and ‘chronic non-communicable conditions’.

Overall, the main cause of death was TB, which was identified in 34% (95% CI 31% to 37%) of the 1028 deceased (table 2). There was a significant decrease in TB as cause of death over time from 43% (95% CI 32% to 53%) in 2002 to a steady proportion of approximately 25% from 2006 onwards (p<0.01). In total, 70% (95% CI 64% to 74%) of the TB cases were on anti-TB treatment. None of the other ‘communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies’ showed a significant trend in time.

Chronic medical conditions were identified in 6% (95% CI 5% to 8%) of deaths overall. The main chronic non-communicable cause of death was non-AIDS-defining malignancy, which showed a prevalence ranging from 1% to 7% over the years. Oesophageal and breast cancer were the most frequent occurring non-AIDS-related malignancies. Accidents, suicide and assault were the main ‘other non-communicable condition’ and caused death in 2% (95% CI 1% to 3%).

Cause of death in patients on ART

In total, 395 patients died while on ART: 268 (68%) within 1 year of starting ART and 127 (32%) while on ART for longer than 1 year. The median CD4 count before death was 56 cells/mm3 (IQR 14–134) in those dying within 1 year of ART compared with 229 cells/mm3 (IQR 145–359) in those dying while on ART for longer than 1 year (p<0.01).

Of the 268 patients who died within 1 year of ART initiation, 208 (78%, 95% CI 72% to 82%) died of a ‘communicable condition or AIDS-defining malignancy’, 8 (3%, 95% CI 2% to 6%) of a ‘chronic non-communicable condition’, 3 (1%, 95% CI 0% to 3%) of an ‘other non-communicable condition’, 29 (11%, 95% CI 8% to 15%) of two ‘communicable conditions and/or AIDS-defining malignancies’ and 3 (1%, 95% CI 0% to 3%) of a combination of a ‘communicable condition or AIDS-defining malignancy’ and a ‘chronic non-communicable condition’. In 17 deceased patients (6%, 95% CI 4% to 10%), no cause of death was identified. The main causes of death were TB (32%, 95% CI 26% to 38%), unspecified infection (19%, 95% CI 15% to 24%), infection with respiratory symptoms (12%, 95% CI 9% to 16%) and Kaposi sarcoma (11%, 95% CI 8% to 15%) (table 3).

Table 3.

Causes of death in deceased on ART

| On ART<1 year (n=268) N (%, 95% CI) | On ART>1 year (n=127) N (%, 95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unknown | 17 (6, 4 to 10) | 22 (17, 12 to 25) |

| Communicable | ||

| HIV | 7 (3, 1 to 5) | 1 (1, 0 to 4) |

| Tuberculosis | 85 (32, 26 to 38) | 18 (14, 9 to 21) |

| Diarrhoeal disease | 7 (3, 1 to 5) | – |

| Respiratory tract infection | 2 (1, 0 to 3) | 1 (1, 0 to 5) |

| Meningitis | 20 (7, 5 to 11) | 8 (8, 4 to 14) |

| Malaria | 5 (2, 1 to 4) | 3 (3, 1 to 8) |

| Kaposi's sarcoma | 29 (11, 8 to 15) | 4 (4, 1 to 9) |

| Other AIDS-defining malignancy | – | 3 (3, 1 to 8) |

| Infection n.s. | 51 (19, 15 to 24) | 19 (18, 12 to 27) |

| Infection with respiratory symptoms | 32 (12, 9 to 16) | 7 (7, 3 to 13) |

| Infection with CNS symptoms | 16 (6, 4 to 9) | 7 (7, 3 to 13) |

| Infection with GI symptoms | 9 (3, 2 to 6) | 2 (2, 1 to 7) |

| Other communicable specified | 5 (2, 1 to 4) | 3 (3, 1 to 8) |

| Chronic NC | ||

| Non-AIDS-defining malignancy | 1 (0, 0 to 2) | 9 (9, 5 to 15) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4 (1, 1 to 4) | 5 (5, 2 to 11) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 1 (0, 0 to 2) | – |

| Cerebrovascular event | – | 1 (1, 0 to 5) |

| GI and hepatic disease | 2 (1, 0 to 3) | 1 (1, 0 to 5) |

| Neurological or psychiatric disorder | 1 (0, 0 to 2) | 1 (1, 0 to 5) |

| Diabetes | 2 (1, 0 to 3) | 5 (5, 2 to 11) |

| Chronic renal disease | – | 3 (3, 1 to 8) |

| Other NC | ||

| Pregnancy-related condition | 3 (1, 0 to 3) | 1 (1, 0 to 5) |

| Accidents, suicide, assault | – | 10 (10, 5 to 17) |

| Postoperative death | – | 1 (1, 0 to 5) |

| Other condition n.s. | – | 3 (3, 1 to 8) |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; NC, non-communicable condition; n.s., non-specified.

Of the 127 patients who died while on ART for >1 year, 62 (49%, 95% CI 40% to 57%) died of a ‘communicable condition or AIDS-defining malignancy’, 18 (14%, 95% CI 9% to 21%) of a ‘chronic non-communicable condition’, 15 (12%, 95% CI 7% to 19%) of an ‘other non-communicable condition’, 3 (2%, 95% CI 0% to 7%) of two ‘communicable conditions and/or AIDS-defining malignancies’ and 7 (6%, 95% CI 3% to 11%) of a combination of a ‘communicable condition or AIDS-defining malignancy’ and a ‘chronic non-communicable condition’. In 22 deceased patients (17%, 95% CI 12% to 25%), no cause of death was identified. The main causes of death were unspecified infection (18%, 95% CI 12% to 27%), TB (14%, 95% CI 9% to 21%), accident, suicide and assault (10%, 95% CI 5% to 17%), malignancies (9%, 95% CI 5% to 15%) and meningitis (8%, 95% CI 4% to 14%) (table 3).

Discussion

In this urban HIV treatment clinic, we observed a steep decline in mortality rate over time, which was caused mainly by a decline in mortality secondary to communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies. A decreasing proportion of patients died of communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies and an increasing proportion died from non-communicable diseases, chronic or non-chronic, or a combination of communicable and non-communicable diseases. Nevertheless, communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies continued to be responsible for the vast majority of deaths, with TB as the main cause of death.

Mortality in HIV-infected individuals has decreased since access to ART has improved. Several other changes in the care and treatment of HIV-infected individuals have occurred over time and have impacted mortality rates. These include joint TB and HIV interventions, earlier initiation of ART and the use of prophylactic treatment for common opportunistic infections among others.2

On a population level, a decreased mortality from HIV-related causes and a relative increase in non-communicable causes of death have been reported from several SSA settings.19 20 Until now, studies from SSA looking in more detail at the causes of death of HIV-infected individuals have focused on mortality in untreated patients or patients who recently started ART. In these patients, the vast majority of deaths are HIV related.8 21 Information on causes of death in patients on ART beyond 1 year is scarce. Our findings among patients on ART for more than 1 year suggest that within this group increasing mortality from non-communicable conditions is evident. Non-AIDS malignancies, mainly breast and oesophageal cancer, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, were the most frequent non-communicable conditions. A study that included 37 hospitalised HIV-infected patients who died while on ART for more than 12 months reported non-communicable conditions as the cause of death in 30%.22 So far, HIV care and treatment efforts have focused mainly on (semi)acute services. With an increasing number of HIV-infected individuals on long-term ART, the incidence of chronic non-communicable conditions will increase.23 This requires a reassessment of the traditional HIV services.

In our study, a high proportion of deaths continued to be due to communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies, even in the recent years. When analysing the characteristics of the patients who died over time, the median CD4 count in the 6 months prior to death was below 200 cells/mm3 in each of the studied years and approximately half of all patients died within 6 months after registration at the clinic. This indicates that many patients who died, even in the recent years, presented to our clinic at a late stage with low CD4 counts and advanced HIV infection. Such patients have a high mortality risk and die almost exclusively of communicable HIV-related conditions.24–27 Recommendations on how to treat this specific group have changed between 2002 and now. The most important change has been to start ART as soon as possible, except in case of cryptococcal or TB meningitis.28 29 This strategy has been shown to decrease mortality.30 31 However, other strategies to prevent late presentation with advanced immunosuppression also need implementation. These include timely detection of HIV infections and adequate linkage to HIV care.

TB caused death in 35% of patients and was clearly the main cause of death. This is in line with the findings of others, who have shown the major contribution of TB to death in the African HIV population.9 21 We found 70% of patients with TB to be on anti-TB treatment. However, this number needs to be interpreted with caution, because being on anti-TB treatment was used as a criterion to assign TB as a cause of death. The category ‘unspecified infection with respiratory complaints’ did not include patients on TB treatment but will most likely contain a high proportion of clinically undiagnosed TB cases. Large changes are taking place in SSA in the field of TB diagnostics. The Xpert MTB/RIF is increasingly being implemented and has shown relatively high sensitivity in HIV-infected patients and the urinary lipoarabinomannan lateral flow assay shows promising results in severely immunosuppressed HIV-infected patients.4 32–35 If and how these novel diagnostic modalities will affect TB-related mortality remains to be fully determined.36

Our study has several shortcomings. Causes of death based on chart review are known to have a relatively poor accuracy in HIV-infected individuals when compared with the gold standard of complete histological autopsy.9 37 38 This is a common problem of all studies that use chart review or verbal autopsy procedures. Moreover, we did not have information on the clinic population as a whole, which forced us to estimate the number of PYFU and prevented us from relating the changes observed in our cohort of deaths to changes in the clinic population. We based the cause of death on information derived from the clinic file. Under-reporting of non-communicable conditions due to lack of awareness or diagnostic modalities may have occurred. Since no information can be ascertained for patients LTFU, deaths occurring in this group were not taken into account. Death causes in those LTFU might differ from the death causes of the patients we included. Lastly, viral loads were not routinely assessed and we could not establish what proportion of death was attributable to virologic failure.

In conclusion, over a time period of 11 years, we observed a decrease in the proportion of deaths from communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies and an increase in the proportion of deaths due to non-communicable conditions. With a growing population on ART, one may assume that changes will continue in this direction. However, increased patient loads within clinics may lead to loss of quality of adherence counselling and support. Also, limited access to treatment monitoring tools such as HIV viral load and increasing first-line ART resistance could act against this trend and result in a continuing high proportion of HIV-related mortality.39–41 Therefore, ongoing monitoring of cause of death is warranted. Innovative and accurate methods to assess this on a population level are needed, since complete autopsies are not widely available. Moreover, despite the decrease, communicable conditions and AIDS-defining malignancies, particularly TB, continue to be responsible for the majority of deaths. This confirms a critical need for better screening strategies, accurate diagnostics and effective prevention strategies for TB and other common opportunistic infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Evelyn Omala and Albert Twinomugisha from Reach Out Mbuya for their logistical support and all volunteers at Reach Out Mbuya, in particular Solomon Wakabi.

Footnotes

Contributors: JAC, RC and SA contributed to the conception and design of the study. JAC, DK, LE and SA were responsible for the acquisition of data. JAC, DK, LE, GM, RC and SA were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. JAC, DK, LE, GM, RC and SA participated in the writing and revising of the manuscript. All the authors have approved the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics: The study protocol received exemption from ethical review from the Higher Degrees Research and Ethics Committee from the School of Public Health of Makerere University, because it involved only archived data that were stripped of identifiers. The study received approval and was registered by the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (registration number SS3132).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data set is available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Baggaley R, Hensen B, Ajose O et al. From caution to urgency: the evolution of HIV testing and counselling in Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:652–8B. 10.2471/BLT.11.100818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact and opportunities. Geneva, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation. Global tuberculosis report 2013 Geneva, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation. WHO monitoring of Xpert MTB/RIF roll-out 2014. http://who.int/tb/laboratory/mtbrifrollout/en/

- 5.World Health Organisation. Estimated adult and child death from AIDS 2011. Geneva, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2012. 2012. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_with_annexes_en_1.pdf (accessed 14 May 2015).

- 7.Kasamba I, Baisley K, Mayanja BN et al. The impact of antiretroviral treatment on mortality trends of HIV-positive adults in rural Uganda: a longitudinal population-based study, 1999–2009. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:e66–73. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02841.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X et al. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2008;22:1897–908. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox JA, Lukande RL, Lucas S et al. Autopsy causes of death in HIV-positive individuals in sub-Saharan Africa and correlation with clinical diagnoses. AIDS Rev 2010;12:183–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayosi BM, Flisher AJ, Lalloo UG et al. The burden of non-communicable diseases in South Africa. Lancet 2009;374:934–47. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61087-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krentz HB, Kliewer G, Gill M. Changing mortality rates and causes of death for HIV-infected individuals living in Southern Alberta, Canada from 1984 to 2003. HIV Med 2005;6:99–106. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palella FJ Jr., Baker RK, Moorman AC et al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;43:27–34. 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada N, Jacobson LP, Cohen M et al. Cause-specific life expectancies after 35 years of age for human immunodeficiency syndrome-infected and human immunodeficiency syndrome-negative individuals followed simultaneously in long-term cohort studies, 1984–2008. Am J Epidemiol 2013;177:116–25. 10.1093/aje/kws321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigatu T. Integration of HIV and noncommunicable diseases in health care delivery in low- and middle-income countries. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:E93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang LW, Alamo S, Guma S et al. Two-year virologic outcomes of an alternative AIDS care model: evaluation of a peer health worker and nurse-staffed community-based program in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;50:276–82. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181988375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amanyire G, Wanyenze R, Alamo S et al. Client and provider perspectives of the efficiency and quality of care in the context of rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010;24:719–27. 10.1089/apc.2010.0108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;380:2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbst AJ, Mafojane T, Newell ML. Verbal autopsy-based cause-specific mortality trends in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2000–2009. Popul Health Metr 2011;9:47 10.1186/1478-7954-9-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chihana M, Floyd S, Molesworth A et al. Adult mortality and probable cause of death in rural northern Malawi in the era of HIV treatment. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:e74–83. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02929.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta A, Nadkarni G, Yang WT et al. Early mortality in adults initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e28691 10.1371/journal.pone.0028691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karstaedt AS. Profile of cause of death assigned to adults on antiretroviral therapy in Soweto. S Afr Med J 2012;102:680–2. 10.7196/samj.5369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narayan KM, Miotti PG, Anand NP et al. HIV and noncommunicable disease comorbidities in the era of antiretroviral therapy: a vital agenda for research in low- and middle-income country settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;67(Suppl 1):S2–7. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montlahuc C, Guiguet M, Abgrall S et al. Impact of late presentation on the risk of death among HIV-infected people in France (2003–2009). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64:197–203. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829cfbfa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingle SM, May M, Uebel K et al. Outcomes in patients waiting for antiretroviral treatment in the Free State Province, South Africa: prospective linkage study. AIDS 2010;24:2717–25. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833fb71f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fairall LR, Bachmann MO, Louwagie GM et al. Effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in a South African program: a cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:86–93. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawn SD, Myer L, Orrell C et al. Early mortality among adults accessing a community-based antiretroviral service in South Africa: implications for programme design. AIDS 2005;19:2141–8. 10.1097/01.aids.0000194802.89540.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Battegay M, Fehr J, Flückiger U et al. Antiretroviral therapy of late presenters with advanced HIV disease. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;62:41–4. 10.1093/jac/dkn169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bahr N, Boulware DR, Marais S et al. Central nervous system immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2013;15:583–93. 10.1007/s11908-013-0378-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanc FX, Sok T, Laureillard D et al. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1471–81. 10.1056/NEJMoa1013911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Severe P, Juste MA, Ambroise A et al. Early versus standard antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected adults in Haiti. N Engl J Med 2010;363:257–65. 10.1056/NEJMoa0910370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theron G, Peter J, van Zyl-Smit R et al. Evaluation of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in a high HIV prevalence setting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:132–40. 10.1164/rccm.201101-0056OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boehme CC, Nicol MP, Nabeta P et al. Feasibility, diagnostic accuracy, and effectiveness of decentralised use of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for diagnosis of tuberculosis and multidrug resistance: a multicentre implementation study. Lancet 2011;377:1495–505. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60438-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peter JG, Theron G, van Zyl-Smit R et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a urine lipoarabinomannan strip-test for TB detection in HIV-infected hospitalised patients. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1211–20. 10.1183/09031936.00201711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawn SD, Kerkhoff AD, Vogt M et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a low-cost, urine antigen, point-of-care screening assay for HIV-associated pulmonary tuberculosis before antiretroviral therapy: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:201–9. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70251-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Churchyard G, McCarthy K, Fielding KL, Stevens W et al. Effect of Xpert MTB/RIF on early mortality in adults with suspected TB: a pragmatic randomized trial. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rana FS, Hawken MP, Mwachari C et al. Autopsy study of HIV-1-positive and HIV-1-negative adult medical patients in Nairobi, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2000;24:23–9. 10.1097/00126334-200005010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinson NA, Karstaedt A, Venter WD et al. Causes of death in hospitalized adults with a premortem diagnosis of tuberculosis: an autopsy study. AIDS 2007;21:2043–50. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282eea47f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wandeler G, Keiser O, Pfeiffer K et al. Outcomes of antiretroviral treatment programs in rural Southern Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;59:e9–16. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823edb6a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keiser O, Tweya H, Braitstein P et al. Mortality after failure of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:251–8. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02445.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nglazi MD, Lawn SD, Kaplan R et al. Changes in programmatic outcomes during 7 years of scale-up at a community-based antiretroviral treatment service in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;56:e1–8. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ff0bdc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]