Abstract

Objectives

Measuring the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and design effect (DE) may help to modify the public health interventions for body mass index (BMI), physical activity and diet according to geographic targeting of interventions in different countries. The purpose of this study was to quantify the level of clustering and DE in BMI, physical activity and diet in 56 low-income, middle-income and high-income countries.

Design

Cross-sectional study design.

Setting

Multicountry national survey data.

Methods

The World Health Survey (WHS), 2003, data were used to examine clustering in BMI, physical activity in metabolic equivalent of task (MET) and diet in fruits and vegetables intake (FVI) from low-income, middle-income and high-income countries. Multistage sampling in the WHS used geographical clusters as primary sampling units (PSU). These PSUs were used as a clustering or grouping variable in this analysis. Multilevel intercept only regression models were used to calculate the ICC and DE for each country.

Results

The median ICC (0.039) and median DE (1.82) for BMI were low; however, FVI had a higher median ICC (0.189) and median DE (4.16). For MET, the median ICC was 0.141 and median DE was 4.59. In some countries, however, the ICC and DE for BMI were large. For instance, South Africa had the highest ICC (0.39) and DE (11.9) for BMI, whereas Uruguay had the highest ICC (0.434) for MET and Ethiopia had the highest ICC (0.471) for FVI.

Conclusions

This study shows that across a wide range of countries, there was low area level clustering for BMI, whereas MET and FVI showed high area level clustering. These results suggested that the country level clustering effect should be considered in developing preventive approaches for BMI, as well as improving physical activity and healthy diets for each country.

Keywords: Body Mass Index (BMI), Physical activity (METs), Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Obesity is a global public health problem emerging almost in all countries, but the geographical distribution of obesity in different countries is not well established. This study provides an important investigation of obesity and associated factors distribution using clustering to develop effective public health policies adapted to each country according to the clustering effect within the country.

This study includes a large sample size from 56 low-income, middle-income and high-income countries.

Neighbourhood and household level data were not available in the World Health Survey; therefore, the neighbourhood and household level ICC and design effect were not analysed in this study.

Introduction

Public health interventions to control obesity for a population can be divided into two broad strategies.1 First, the whole population approach that targets everyone in the population. If everyone in the population is not at risk, this can be expensive and inefficient. Second, a high-risk approach, narrowly targets high-risk groups. The approach can deliver substantial resources to many of those at risk, but may fail to reach everyone at risk.2 3 The challenge of where to target interventions may be exacerbated by uniform policies that are developed at national or supranational levels, without giving due consideration to the actual distribution of need within countries at the state or district level.4

If a health outcome or risk factor is distributed (geographically) uniformly in a population, then policies that target resources may narrowly miss many of those in need.1 Conversely, if a health outcome or risk factor is geographically clustered, then a policy that distributes resources uniformly will see some resources delivered to areas at the greatest risk, but will see as many resources distributed to areas at the smallest risk.4 5 Achieving the most cost-effective distribution of resources is a perennial problem for governments that require an understanding of how risk factors and health outcomes are actually geographically clustered. One of the few studies that looked at the geographical clustering of a health outcome across countries considered stunting and wasting in 46 low-income countries covered by the Demographic and Health Survey.2 That study found that stunting and wasting were (on average) not highly clustered, and geographically targeted interventions were likely to lead to a substantial undercoverage. Another multicountry study examining clustering of diarrhoea in four low-income countries found a substantial country variation in the design effect (DE) from as low as 2 to as high as 7.6

These kinds of analyses, however, have not been extended to other health outcomes and risk factors; nor have they been extended to higher income countries. Surprisingly, little is actually known about the geographical concentration of obesity, for instance, and associated risk factors such as physical activity and healthy food consumption across countries. This is an important gap, given the significance of obesity as a major contributor to the global burden of disease,7 and the effect that geographical clustering may have on the targeting of interventions. In this study, we examine the extent to which obesity and risk factors for obesity are geographically clustered in 56 low-income, middle-income and high-income countries.

Methods

Study population

The data from the World Health Survey (WHS), 2003, provide an important opportunity to examine the geographical clustering of obesity (body mass index, BMI) and associated risk factors (physical activity and diet). The WHS was conducted in 70 countries across five continents (Europe, Australia, South America, Asia and Africa) to provide valid, reliable, representative and comparable population data on the health status of adults aged 18 years and older. All samples were probabilistically selected with every individual being assigned a known non-zero probability of being selected. Data from six countries were excluded from this study because the samples were not nationally represented (China, Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, India and the Russian Federation).

In 60 of the remaining WHS countries, a staged process in which primary sampling units (PSUs) were selected at random and then within selected PSUs, further stages of sampling occurred. A further four countries were excluded because of anomalies in the sampling strategy or missing information (Israel, Luxembourg, Norway and Zambia). Data from the remaining 56 countries were used to analyse the clustering of BMI. However, a further eight countries were excluded from the physical activity and diet analyses because of missing data (see below).

Post-stratification corrections were made to sampling weights to adjust for the population distribution represented by the UN Statistics Division8 and non-response.7 9 More detailed information on the sampling approach can be found elsewhere.10

Variables

BMI was estimated from self-reported height and weight responses, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height squared in metres. Physical activity was measured in terms of metabolic equivalent task (MET). MET is defined as the energy spent sitting quietly (equivalent to (4.184 kJ)/kg/h).11 In the WHS, to assess physical activity respondents were asked to report the number of days and the duration of the vigorous, moderate and walking activities they undertook during the past week. Taking the different intensities of the activity components into account, reported weekly minutes spent were multiplied by 8 MET for vigorous activities, by 4 MET for moderate activities and by 3.3 MET for walking. Energy expenditure per individual was obtained by adding the MET-min of the three activity components.3 Diet was operationalised as the number of serves of fruit and vegetable (FVI) in a typical day, using two questions on average FVI per day.12 Data on MET were missing for Australia, Finland, France, Ireland, Latvia, Portugal and Sweden. Data on FVI were missing for Australia, Finland, France, Ireland, Mexico, Portugal and Sweden.

Grouping or clustering variable

Multistage sampling in the WHS used statistical enumeration areas as the PSUs. These were highlighted in the WHO sampling documentation as naturally occurring groupings with clear, non-overlapping boundaries.7 13 The PSUs were used as clustering or grouping variables in this analysis.

Data analysis

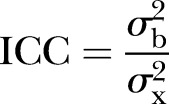

The standard measure of the extent to which observations are correlated by cluster (area or sampling unit) is the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC):

|

1 |

where  is the between-cluster variance,

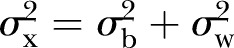

is the between-cluster variance,  is the total variance (

is the total variance ( ), and

), and  is the within-cluster variance in the outcome variable.

is the within-cluster variance in the outcome variable.

Intercept-only multilevel regression models were used to produce estimates of the ICC.2

14 These intercept-only models do not contain any explanatory variable. It only decomposes the variance of Y into two independent components:  , which is the variance of the lowest level errors eij, and

, which is the variance of the lowest level errors eij, and  , which is the variance of the highest level errors u0j. Using this model, the ICC was calculated using equation 1. The DE for each country was also calculated using the formula mentioned in the introduction section in equation 2.

, which is the variance of the highest level errors u0j. Using this model, the ICC was calculated using equation 1. The DE for each country was also calculated using the formula mentioned in the introduction section in equation 2.

A better-known measure related to the ICC is the ‘design effect’ due to clustering, defined as ‘the loss of effectiveness (resulting from) use of cluster sampling, instead of simple random sampling’. The relationship between design effect, cluster size and ICC is represented in the following equation:

| 2 |

where DE is the design effect and m is the average number of respondents per cluster, or average cluster size.2 14 The ICC is a portable parameter that can be compared across the countries since it does not depend on the cluster size or on the numbers of clusters (although it may be imprecisely estimated due to sampling variability). The design effect, however, is affected by the sample design, and is strongly dependent on cluster size.6 The statistical analysis was done using the package R-project.15

Results

A total of 56 countries for BMI and 48 countries for MET and FVI variables were used in this analysis, and descriptive statistics for the countries can be found in table 1. The total sample size was smallest for Latvia (n=856) and greatest for Mexico (n=38 746). There was a wide variation in the within PSU sample size, ranging from n=1 to n=375 across the countries. The median within the PSU sample size varied across countries from 1 to 133. Interestingly, 21 (42%) countries had a minimum PSU sample size of 1, but according to the WHS sampling guidelines all PSUs should have a sample size between 20 and 30.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of sample size, PSU characteristics and ICC and DE for BMI, MET and FVI

| Country | Sample size | Number of PSUs | Mean PSU size | BMI |

MET |

FVI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||||

| Australia | 1845 | 125 | 14.8 | 26.5 (5.9) | 25.7 (6.4) | – | – | – | – |

| Bangladesh | 5552 | 186 | 29.8 | 21.7 (3.8) | 21.3 (4.8) | 9278 (9968) | 5665 (12 417) | 5.2 (2.7) | 5.0 (3.0) |

| Bosnia | 1028 | 112 | 9.2 | 25.0 (3.7) | 24.4 (4.3) | 7750 (8975) | 4314 (8687) | 3.3 (1.5) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Brazil | 5000 | 250 | 20.0 | 24.6 (4.5) | 24.0 (5.5) | 6265 (8639) | 2772 (7320) | 1.8 (2.5) | 1.0 (3.0) |

| Burkina Faso | 4822 | 148 | 32.6 | 22.8 (3.4) | 22.6 (3.3) | 11 218 (11 396) | 7518 (13 272) | 3.2 (3.7) | 2.0 (3.0) |

| Chad | 4652 | 103 | 45.2 | 25.1 (7.6) | 23.5 (5.6) | 9284 (11 933) | 4135 (13 117) | 3.8 (5.5) | 2.0 (5.0) |

| China | 3993 | 30 | 133.1 | 22.0 (3.2) | 21.6 (3.8) | 7391 (8313) | 4452 (9288) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.0) |

| Comoros | 1752 | 49 | 35.8 | 23.0 (3.7) | 22.7 (4.3) | 11 488 (8975) | 9492 (11 681) | 3.7 (2.0) | 3.0 (3.0) |

| Congo | 2490 | 109 | 22.8 | 23.3 (4.4) | 22.9 (4.2) | 3577 (6530) | 1188 (4397) | 3.2 (3.1) | 3.0 (3.0) |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 3178 | 172 | 18.5 | 23.3 (4.4) | 22.9 (4.2) | 9794 (11 512) | 5544 (13 622) | 3.7 (4.2) | 2.0 (3.0) |

| Croatia | 990 | 184 | 5.4 | 26.0 (4.4) | 25.5 (5.8) | 8574 (9857) | 4746 (10 067) | 2.6 (1.8) | 2.0 (1.0) |

| Czech Republic | 935 | 192 | 4.9 | 26.0 (4.6) | 25.5 (6.1) | 7854 (8090) | 5118 (9083) | 3.1 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.0) |

| Dominican Republic | 4534 | 256 | 17.7 | 24.7 (5.0) | 23.9 (6.0) | 3933 (7114) | 990 (4010) | 3.1 (2.9) | 3.0 (3.0) |

| Ecuador | 4627 | 220 | 21.0 | 26.0 (7.9) | 24.2 (5.7) | 2879 (6127) | 2031 (2772) | 2.0 (2.3) | 2.0 (3.0) |

| Estonia | 1012 | 49 | 20.7 | 25.8 (4.7) | 25.0 (6.1) | 13 006 (12 489) | 9171 (15 479) | 3.4 (2.5) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Ethiopia | 4938 | 99 | 49.9 | 21.4 (3.0) | 20.9 (3.3) | 11 503 (10 245) | 9231 (14 812) | 1.9 (2.7) | 0.0 (3.0) |

| Finland | 1013 | 169 | 6.0 | 26.0 (4.4) | 25.4 (5.5) | – | – | – | – |

| France | 1008 | 116 | 8.7 | 23.6 (4.0) | 23.0 (5.1) | – | – | – | – |

| Georgia | 2752 | 68 | 40.5 | 25.1 (4.2) | 24.7 (5.1) | 7959 (8169) | 533 (9377) | 3.4 (2.2) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Ghana | 3932 | 290 | 13.6 | 22.7 (4.9) | 22.0 (4.6) | 8471 (9842) | 4700 (11 066) | 6.4 (5.0) | 5.0 (4.0) |

| Hungary | 1419 | 194 | 7.3 | 26.2 (5.0) | 25.9 (6.5) | 10 279 (10 376) | 6735 (12 960) | 3.2 (2.1) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| India | 9985 | 379 | 26.3 | 20.4 (3.9) | 19.8 (4.4) | 10 937 (11 004) | 7599 (14 364) | 4.4 (7.9) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Ireland | 1014 | 100 | 10.1 | 25.3 (4.5) | 24.7 (5.4) | – | – | – | – |

| Kazakhstan | 4496 | 66 | 68.1 | 25.2 (4.6) | 24.4 (5.2) | 6199 (6062) | 4518 (6863) | 2.6 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.0) |

| Kenya | 4416 | 275 | 16.1 | 22.5 (4.3) | 21.8 (4.9) | 11 204 (9356) | 9633 (14 342) | 2.8 (1.7) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Laos | 4889 | 250 | 19.6 | 23.4 (4.4) | 22.9 (4.2) | 9021 (9076) | 6132 (10 027) | 3.3 (1.9) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Latvia | 856 | 134 | 6.4 | 26.3 (4.8) | 25.6 (6.1) | – | – | 3.4 (2.1) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Malawi | 5300 | 71 | 74.6 | 23.8 (5.2) | 23.1 (5.1) | 8922 (8319) | 6693 (11 154) | 6.3 (4.7) | 5.0 (3.0) |

| Malaysia | 6040 | 399 | 15.1 | 24.0 (5.9) | 23.1 (5.9) | 6557 (9102) | 2701 (7784) | 3.1 (1.6) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Mali | 4271 | 284 | 15.0 | 28.2 (24.0) | 21.8 (19.1) | 10 232 (13 803) | 2880 (17 013) | 2.7 (5.0) | 0.0 (3.0) |

| Mauritania | 3776 | 158 | 23.9 | 24.6 (6.9) | 23.4 (5.8) | 2435 (6127) | 99 (1525) | 1.3 (3.1) | 1.0 (2.0) |

| Mauritius | 3888 | 100 | 38.9 | 23.6 (5.1) | 23.0 (5.4) | 5365 (6389) | 3192 (6160) | 2.9 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.0) |

| Mexico | 38 746 | 797 | 48.6 | 25.9 (4.6) | 25.4 (5.4) | 7338 (8398) | 4605 (9011) | – | – |

| Morocco | 4716 | 250 | 18.9 | 24.2 (4.5) | 23.6 (5.4) | 1731 (1587) | 1299 (2076) | 2.9 (2.5) | 2.0 (3.0) |

| Myanmar | 5886 | 110 | 53.5 | 21.1 (2.9) | 20.8 (3.4) | 7569 (8064) | 4320 (10 080) | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Namibia | 4248 | 229 | 18.6 | 23.9 (6.2) | 22.8 (6.1) | 4230 (6942) | 1394 (4940) | 2.1 (2.6) | 2.0 (3.0) |

| Nepal | 8688 | 292 | 29.8 | 21.1 (3.6) | 20.6 (4.0) | 11 599 (10 044) | 9168 (13 614) | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.0 (0.0) |

| Pakistan | 6379 | 355 | 18.0 | 23.9 (7.2) | 22.6 (5.5) | 7062 (8960) | 3586 (9120) | 1.9 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.0) |

| Paraguay | 5143 | 498 | 10.3 | 24.9 (5.8) | 24.1 (5.3) | 5727 (5984) | 3672 (7601) | 4.1 (2.9) | 4.0 (3.0) |

| Philippines | 10 078 | 240 | 42.0 | 21.9 (4.0) | 21.3 (4.4) | 10 677 (9588) | 7886 (12 158) | 3.6 (2.2) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Portugal | 1020 | 100 | 10.2 | 26.0 (4.4) | 25.4 (5.6) | – | – | – | – |

| Russia | 4421 | 123 | 35.9 | 25.8 (4.5) | 25.3 (5.4) | 9393 (10 151) | 6426 (10 610) | 3.0 (2.1) | 2.0 (2.0) |

| Senegal | 3219 | 259 | 12.4 | 22.9 (5.5) | 22.2 (5.4) | 5860 (9702) | 1765 (7552) | 2.3 (3.4) | 2.0 (3.0) |

| Slovakia | 2514 | 312 | 8.1 | 24.7 (4.6) | 24.2 (5.8) | 4436 (6253) | 2346 (6132) | 2.1 (2.4) | 2.0 (3.0) |

| South Africa | 2324 | 183 | 12.7 | 29.1 (10.8) | 26.4 (9.5) | 3570 (6524) | 1172 (3786) | 3.8 (2.8) | 3.0 (3.0) |

| Spain | 6364 | 997 | 6.4 | 26.0 (4.2) | 25.6 (5.3) | 3064 (4776) | 1386 (3014) | 3.5 (1.8) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Sri Lanka | 6732 | 145 | 46.4 | 21.4 (4.8) | 20.7 (5.1) | 10 176 (9975) | 7017 (13 611) | 3.7 (2.4) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Swaziland | 3070 | 96 | 32.0 | 28.5 (8.6) | 26.7 (7.4) | 2870 (6259) | 213 (2784) | 2.6 (2.9) | 2.0 (4.0) |

| Sweden | 1000 | 53 | 18.9 | 24.8 (4.0) | 24.4 (4.9) | – | – | – | – |

| Tunisia | 5065 | 265 | 19.1 | 24.3 (4.3) | 23.9 (5.0) | 6714 (8598) | 3459 (8712) | 2.6 (1.4) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Turkey | 11 218 | 472 | 23.8 | 25.4 (5.0) | 24.7 (5.7) | 3183 (5726) | 1040 (3412) | 3.1 (1.9) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| UAE | 1180 | 60 | 19.7 | 26.5 (5.5) | 25.8 (5.3) | 1745 (3967) | 693 (1716) | 3.6 (1.9) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Ukraine | 2802 | 113 | 24.8 | 25.9 (4.8) | 25.4 (5.7) | 11 773 (12 071) | 8316 (13 947) | 5.2 (4.8) | 4.0 (4.0) |

| Uruguay | 2978 | 61 | 48.8 | 25.5 (4.6) | 24.8 (5.2) | 4550 (6650) | 1927 (5009) | 3.6 (2.3) | 3.0 (3.0) |

| Vietnam | 3492 | 137 | 25.5 | 20.1 (2.3) | 19.9 (2.8) | 11 229 (11 560) | 8079 (10 019) | 3.5 (1.7) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Zimbabwe | 4072 | 130 | 31.3 | 26.4 (10.8) | 23.9 (5.4) | 8062 (8324) | 5678 (9768) | 3.0 (2.5) | 3.0 (2.0) |

BMI, body mass index; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; DE, design effect; FVI, fruits and vegetable intake; IQR, interquartile range; MET, metabolic equivalent of task; PSU, primary sampling units; SD, standard deviation.

Results for the ICC and DE for each country are given in tables 2 and 3. Table 4 shows the overall descriptive analysis of the ICC and DE for BMI, MET and FVI across all 56 countries. BMI had the smallest median ICC and DE, whereas FVI had the largest median ICC and DE. The median DE for BMI was <2. In some countries, however, the ICC and DE for BMI were large; in South Africa, for instance, the BMI ICC was 0.399 and in China the DE was 12.0 (tables 2 and 3). For BMI, MET and FVI, the minimum ICC and DE were very small. Online supplementary appendix A shows correlation among the ICC for BMI, ICC for MET and ICC for FVI in all 48 countries.

Table 2.

ICC with CI for BMI, MET and FVI

| Country | BMI |

MET |

FVI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | CI | ICC | CI | ICC | CI | |

| Australia | 0.001 | 0.000 to 0.023 | – | – | – | – |

| Bangladesh | 0.001 | 0.000 to 0.091 | 0.082 | 0.061 to 0.103 | 0.211 | 0.171 to 0.250 |

| Bosnia | 0.056 | 0.023 to 0.103 | 0.263 | 0.192 to 0.330 | 0.333 | 0.248 to 0.401 |

| Brazil | 0.023 | 0.014 to 0.044 | 0.119 | 0.092 to 0.145 | 0.128 | 0.101 to 0.152 |

| Burkina Faso | 0.072 | 0.047 to 0.106 | 0.131 | 0.099 to 0.162 | 0.258 | 0.207 to 0.302 |

| Chad | 0.134 | 0.095 to 9.172 | 0.386 | 0.316 to 0.447 | 0.338 | 0.255 to 0.383 |

| China | 0.083 | 0.040 to 0.124 | 0.358 | 0.226 to 0.472 | 0.329 | 0.197 to 0.432 |

| Comoros | 0.037 | 0.015 to 0.061 | 0.102 | 0.059 to 0.145 | 0.085 | 0.045 to 0.125 |

| Congo | 0.065 | 0.034 to 0.097 | 0.082 | 0.048 to 0.116 | 0.292 | 0.218 to 0.354 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 0.017 | 0.002 to 0.033 | 0.219 | 0.176 to 0.261 | 0.200 | 0.158 to 0.239 |

| Croatia | 0.001 | 0.000 to 0.048 | 0.171 | 0.103 to 0.229 | 0.190 | 0.126 to 0.254 |

| Czech Republic | 0.037 | 0.001 to 0.089 | 0.112 | 0.050 to 0.171 | 0.103 | 0.044 to 0.158 |

| Dominican Republic | 0.014 | 0.001 to 0.030 | 0.034 | 0.019 to 0.050 | 0.117 | 0.091 to 0.146 |

| Ecuador | 0.032 | 0.017 to 0.050 | 0.121 | 0.092 to 0.150 | 0.091 | 0.067 to 0.114 |

| Estonia | 0.001 | 0.000 to 0.019 | 0.087 | 0.029 to 0.140 | 0.097 | 0.033 to 0.160 |

| Ethiopia | 0.038 | 0.001 to 0.077 | 0.218 | 0.163 to 0.269 | 0.471 | 0.393 to 0.540 |

| Finland | 0.001 | 0.000 to 0.080 | – | – | – | – |

| France | 0.073 | 0.026 to 0.121 | – | – | – | – |

| Georgia | 0.028 | 0.012 to 0.047 | 0.237 | 0.167 to 0.304 | 0.356 | 0.262 to 0.423 |

| Ghana | 0.132 | 0.103 to 0.170 | 0.141 | 0.112 to 0.172 | 0.093 | 0.068 to 0.117 |

| Hungary | 0.032 | 0.001 to 0.065 | 0.126 | 0.075 to 0.171 | 0.016 | 0.090 to 0.187 |

| India | 0.076 | 0.061 to 0.093 | 0.121 | 0.102 to 0.142 | 0.470 | 0.430 to 0.505 |

| Ireland | 0.092 | 0.043 to 0.144 | – | – | – | – |

| Kazakhstan | 0.033 | 0.017 to 0.051 | 0.238 | 0.170 to 0.301 | 0.252 | 0.184 to 0.321 |

| Kenya | 0.102 | 0.077 to 0.127 | 0.124 | 0.097 to 0.152 | 0.177 | 0.142 to 0.207 |

| Laos | 0.081 | 0.058 to 0.103 | 0.257 | 0.219 to 0.297 | 0.135 | 0.110 to 0.163 |

| Latvia | 0.001 | 0.000 to 0.040 | – | – | 0.286 | 0.206 to 0.357 |

| Malawi | 0.039 | 0.022 to 0.055 | 0.171 | 0.119 to 0.221 | 0.274 | 0.200 to 0.336 |

| Malaysia | 0.021 | 0.007 to 0.035 | 0.121 | 0.099 to 0.144 | 0.090 | 0.071 to 0.111 |

| Mali | 0.384 | 0.310 to 0.450 | 0.172 | 0.139 to 0.201 | 0.231 | 0.195 to 0.268 |

| Mauritania | 0.128 | 0.090 to 0.160 | 0.267 | 0.212 to 0.315 | 0.170 | 0.130 to 0.207 |

| Mauritius | 0.061 | 0.038 to 0.089 | 0.131 | 0.091 to 0.163 | 0.237 | 0.181 to 0.296 |

| Mexico | 0.033 | 0.026 to 0.040 | 0.075 | 0.066 to 0.083 | – | – |

| Morocco | 0.026 | 0.001 to 0.052 | 0.063 | 0.044 to 0.083 | 0.176 | 0.141 to 0.204 |

| Myanmar | 0.076 | 0.540 to 0.983 | 0.283 | 0.223 to 0.337 | 0.463 | 0.393 to 0.523 |

| Namibia | 0.093 | 0.067 to 0.120 | 0.098 | 0.072 to 0.124 | 0.171 | 0.138 to 0.205 |

| Nepal | 0.068 | 0.043 to 0.093 | 0.155 | 0.129 to 0.178 | 0.055 | 0.041 to 0.068 |

| Pakistan | 0.124 | 0.097 to 0.157 | 0.216 | 0.184 to 0.245 | 0.156 | 0.130 to 0.182 |

| Paraguay | 0.054 | 0.037 to 0.074 | 0.109 | 0.086 to 0.130 | 0.097 | 0.075 to 0.118 |

| Philippines | 0.030 | 0.018 to 0.040 | 0.134 | 0.106 to 0.160 | 0.176 | 0.145 to 0.206 |

| Portugal | 0.067 | 0.020 to 0.012 | – | – | – | – |

| Russia | 0.034 | 0.015 to 0.052 | 0.200 | 0.146 to 0.248 | 0.217 | 0.160 to 0.271 |

| Senegal | 0.088 | 0.049 to 0.126 | 0.067 | 0.044 to 0.092 | 0.050 | 0.028 to 0.073 |

| Slovakia | 0.062 | 0.022 to 0.107 | 0.291 | 0.219 to 0.353 | 0.090 | 0.049 to 0.136 |

| South Africa | 0.399 | 0.331 to 0.463 | 0.324 | 0.265 to 0.374 | 0.341 | 0.281 to 0.395 |

| Spain | 0.041 | 0.023 to 0.057 | 0.234 | 0.207 to 0.261 | 0.079 | 0.060 to 0.099 |

| Sri Lanka | 0.172 | 0.133 to 0.204 | 0.200 | 0.158 to 0.241 | 0.309 | 0.254 to 0.354 |

| Swaziland | 0.018 | 0.000 to 0.042 | 0.128 | 0.088 to 0.167 | 0.212 | 0.154 to 0.263 |

| Sweden | 0.016 | 0.000 to 0.043 | – | – | – | – |

| Tunisia | 0.041 | 0.025 to 0.059 | 0.213 | 0.178 to 0.241 | 0.255 | 0.219 to 0.290 |

| Turkey | 0.022 | 0012 to 0.032 | 0.053 | 0.021 to 0.087 | 0.091 | 0.076 to 0.108 |

| UAE | 0.004 | 0.001 to 0.024 | 0.054 | 0.021 to 0.087 | 0.201 | 0.133 to 0.267 |

| Ukraine | 0.033 | 0.006 to 0.059 | 0.336 | 0.264 to 0.392 | 0.298 | 0.230 to 0.359 |

| Uruguay | 0.035 | 0.013 to 0.057 | 0.434 | 0.327 to 0.521 | 0.112 | 0.066 to 0.158 |

| Vietnam | 0.108 | 0.077 to 0.141 | 0.351 | 0.283 to 0.404 | 0.444 | 0.374 to 0.501 |

| Zimbabwe | 0.232 | 0.171 to 0.290 | 0.070 | 0.044 to 0.092 | 0.128 | 0.044 to 0.092 |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; FVI, fruits and vegetable intake; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; MET, metabolic equivalent of task.

Table 3.

DE and CI for BMI, MET and FVI

| Country | BMI |

MET |

FVI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | CI | DE | CI | DE | CI | |

| Australia | 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.3 | – | – | – | – |

| Bangladesh | 1.0 | 1.0 to 3.6 | 3.4 | 2.7 to 4.0 | 7.1 | 5.9 to 8.1 |

| Bosnia | 1.5 | 1.1 to 1.8 | 3.2 | 2.4 to 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.1 to 4.2 |

| Brazil | 1.4 | 1.1 to 1.6 | 3.3 | 2.7 to 3.7 | 3.4 | 2.9 to 3.9 |

| Burkina Faso | 3.3 | 2.1 to 4.3 | 5.1 | 4.1 to 6.1 | 9.2 | 7.5 to 10.5 |

| Chad | 6.9 | 5.2 to 8.5 | 18.1 | 14.8 to 20.9 | 15.9 | 12.3 to 17.6 |

| China | 12.0 | 6.7 to 16.9 | 48.3 | 31.1 to 61.6 | 44.5 | 28.8 to 59.1 |

| Comoros | 2.3 | 1.4 to 3.1 | 4.5 | 2.9 to 6.0 | 4.0 | 2.5 to 5.3 |

| Congo | 2.4 | 1.7 to 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.1 to 3.5 | 7.4 | 5.7 to 8.7 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 1.3 | 1.0 to 1.5 | 4.8 | 4.0 to 5.5 | 4.5 | 3.7 to 5.1 |

| Croatia | 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.4 to 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.5 to 2.0 |

| Czech Republic | 1.1 | 1.0 to 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 to 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.1 to 1.6 |

| Dominican Republic | 1.2 | 1.0 to 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.3 to 1.8 | 3.0 | 2.5 to 3.3 |

| Ecuador | 1.6 | 1.3 to 1.9 | 3.4 | 2.8 to 3.9 | 2.8 | 2.3 to 3.2 |

| Estonia | 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.3 | 2.7 | 1.6 to 3.8 | 2.9 | 1.6 to 4.0 |

| Ethiopia | 2.9 | 1.1 to 4.8 | 11.7 | 8.9 to 14.1 | 24.0 | 20.3 to 27.1 |

| Finland | 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.4 | – | – | – | – |

| France | 1.6 | 1.1 to 1.9 | – | – | – | – |

| Georgia | 2.1 | 1.4 to 2.8 | 10.4 | 7.6 to 12.8 | 15.1 | 11.4 to 17.6 |

| Ghana | 2.7 | 2.3 to 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.3 to 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.8 to 2.4 |

| Hungary | 1.2 | 1.0 to 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.4 to 2.0 | 1.1 | 1.5 to 2.1 |

| India | 2.9 | 2.5 to 3.3 | 4.1 | 3.5 to 4.5 | 12.9 | 11.8 to 13.7 |

| Ireland | 1.8 | 4.9 to 5.6 | – | – | – | – |

| Kazakhstan | 3.2 | 2.1 to 4.4 | 17.0 | 12.3 to 21.1 | 17.9 | 13.0 to 22.2 |

| Kenya | 2.5 | 2.1 to 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.4 to 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.1 to 4.1 |

| Laos | 2.5 | 2.1 to 2.9 | 5.8 | 5.0 to 6.4 | 3.5 | 2.9 to 4.0 |

| Latvia | 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.2 | – | – | 2.5 | 2.1 to 2.9 |

| Malawi | 3.9 | 2.6 to 5.1 | 13.6 | 9.8 to 17.1 | 21.2 | 15.8 to 25.8 |

| Malaysia | 1.3 | 1.1 to 1.4 | 2.7 | 2.4 to 3.0 | 2.3 | 1.9 to 2.5 |

| Mali | 6.4 | 5.3 to 7.3 | 3.4 | 2.9 to 3.8 | 4.2 | 3.7 to 4.7 |

| Mauritania | 3.9 | 3.1 to 4.6 | 7.1 | 5.8 to 8.1 | 4.9 | 3.9 to 5.6 |

| Mauritius | 3.3 | 2.4 to 4.3 | 6.0 | 4.4 to 7.3 | 10.0 | 8.0 to 12.0 |

| Mexico | 2.6 | 2.2 to 2.8 | 4.6 | 4.2 to 4.9 | – | – |

| Morocco | 1.5 | 1.0 to 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.7 to 2.4 | 4.2 | 3.5 to 4.7 |

| Myanmar | 5.0 | 3.7 to 6.1 | 15.9 | 12.7 to 18.6 | 25.3 | 21.5 to 28.5 |

| Namibia | 2.6 | 2.1 to 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.2 to 3.1 | 4.0 | 3.3 to 4.5 |

| Nepal | 3.0 | 2.2 to 3.6 | 5.5 | 4.7 to 6.1 | 2.6 | 2.1 to 2.9 |

| Pakistan | 3.1 | 2.5 to 3.6 | 4.7 | 4.1 to 5.2 | 3.7 | 3.2 to 4.0 |

| Paraguay | 1.5 | 1.3 to 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.7 to 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.6 to 2.0 |

| Philippines | 2.2 | 1.7 to 2.6 | 6.5 | 5.4 to 7.4 | 8.2 | 7.0 to 9.4 |

| Portugal | 1.6 | 1.2 to 2.0 | – | – | – | – |

| Russia | 2.2 | 1.6 to 3.0 | 8.0 | 6.7 to 10.6 | 8.6 | 7.3 to 11.4 |

| Senegal | 2.0 | 1.5 to 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.4 to 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 to 1.8 |

| Slovakia | 1.4 | 1.1 to 1.7 | 3.1 | 2.5 to 3.5 | 1.6 | 1.3 to 1.9 |

| South Africa | 5.7 | 4.8 to 6.4 | 4.8 | 4.0 to 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.3 to 5.6 |

| Spain | 1.2 | 1.1 to 1.3 | 2.3 | 2.1 to 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 to 1.5 |

| Sri Lanka | 8.8 | 6.9 to 10.5 | 10.1 | 8.1 to 11.8 | 15.0 | 12.5 to 17.2 |

| Swaziland | 1.6 | 1.0 to 2.2 | 5.0 | 3.7 to 6.2 | 7.6 | 5.7 to 9.2 |

| Sweden | 1.3 | 1.0 to 1.7 | – | – | – | – |

| Tunisia | 1.7 | 1.4 to 2.0 | 4.9 | 4.2 to 5.4 | 5.6 | 4.9 to 6.3 |

| Turkey | 1.5 | 1.2 to 1.7 | 2.2 | 1.9 to 2.4 | 3.1 | 2.7 to 3.4 |

| UAE | 1.1 | 1.0 to 1.4 | 2.0 | 1.4 to 2.6 | 4.8 | 3.4 to 5.9 |

| Ukraine | 1.8 | 1.1 to 2.4 | 9.0 | 7.2 to 10.4 | 8.1 | 6.5 to 9.4 |

| Uruguay | 2.7 | 1.6 to 3.7 | 21.7 | 16.7 to 25.8 | 6.4 | 4.1 to 8.7 |

| Vietnam | 3.6 | 2.8 to 4.4 | 9.6 | 8.04 to 10.9 | 11.9 | 10.1 to 13.3 |

| Zimbabwe | 8.0 | 6.2 to 9.7 | 3.1 | 2.3 to 3.8 | 4.9 | 3.8 to 5.9 |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; DE, design effect; FVI, fruits and vegetable intake; MET, metabolic equivalent of task.

Table 4.

Descriptive analysis of ICC and DE of BMI, MET and FVI in 56 countries

| BMI |

MET |

FVI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | DE | ICC | DE | ICC | DE | |

| Minimum | 0.001 | 1.0 | 0.034 | 1.4 | 0.016 | 1.1 |

| Maximum | 0.399 | 12.0 | 0.434 | 48.3 | 0.471 | 44.5 |

| Median | 0.039 | 1.82 | 0.141 | 4.59 | 0.189 | 4.16 |

| IQR | 0.056 | 1.61 | 0.127 | 4.16 | 0.182 | 5.43 |

BMI, body mass index; DE, design effect; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; FVI, fruits and vegetable intake; MET, metabolic equivalent of task.

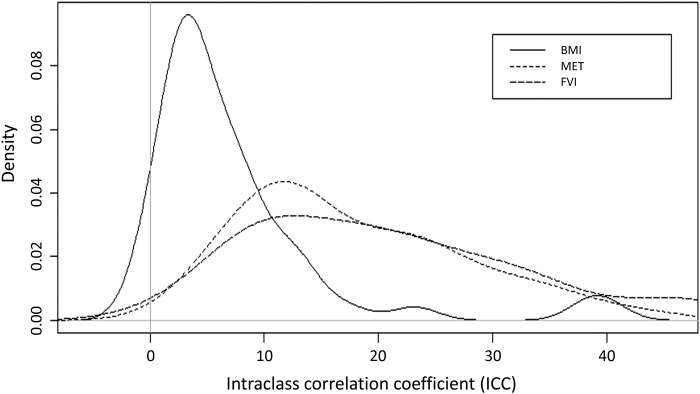

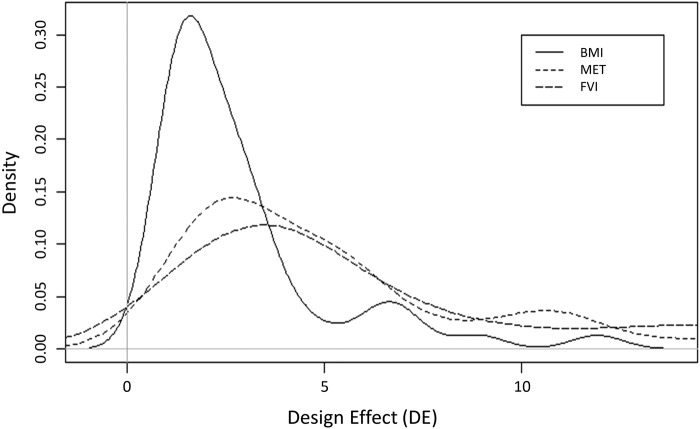

Figures 1 and 2 show the kernel-smoothed distribution of the ICC and DE for BMI, MET and FVI. The distribution of DE is somewhat similar for the three variables, showing a unimodal peak with a DE considerably <10. The picture for the distribution of the ICC is somewhat different. The kernel-smoothed distribution of the ICC for BMI median below 0.05, both MET and FVI showed great clustering with medians around three times and five times greater, respectively.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the values of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for body mass index (BMI), metabolic equivalent of task (MET) and fruits and vegetable intake (FVI) in 48 countries.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the values of the design effect (DE) for body mass index (BMI), metabolic equivalent of task (MET) and fruits and vegetable intake (FVI) in 56 countries.

Discussion

This study explored the area level variation (ICC) in BMI, MET and FVI for 56 countries from the WHS data. This study shows that across a wide range of countries, there was low area level clustering for BMI, whereas MET and FVI showed high area level clustering. These results suggested that, in most of the countries, variation in BMI is determined at levels other than the area level, perhaps at the household or even the individual level.16 These results also suggest whole population approaches (eg, legislation to reduce sugar consumption) might be more appropriate, compared to a targeted population approach.1

However, the ICC for BMI for individual countries varied substantially from a minimum of 0.001 in Croatia and the UAE to a maximum of 0.399 for South Africa. These results indicate that universal strategies to control obesity might not show consistently effective results in all the countries.16 Where some strategies might be effective in the Dominican Republic (ICC=0.014) and Finland (ICC=0.001), they might not be equally effective in Sri Lanka (ICC=0.172) and Zimbabwe (ICC=0.232). Therefore, each nation should modify the WHO or other international strategies according to the country's need in terms of clustering in areas (ICC). Countries with a low ICC (countries towards the left side of the graph in figure 1) should consider giving more emphasis to whole population approaches. The approach of countries such as Denmark, Austria, Iceland and Switzerland, which have banned the use of trans fatty acids in food processing completely, comes to mind.11 Countries with a high ICC (countries towards the right side of the graph in figure 1) should consider the addition of targeted population approaches together with whole population approach. Here, the example of Mexico's Oportunidades programme, which aimed to assist households on low incomes identified as eligible through strict targeting, comes to mind. Around 6.5 million households were enrolled in the programme, most of them in rural and semi-urban areas.17

However, the ICC for MET and FVI was high with more than 81% of countries with an ICC>0.10. The results suggest the potential for implementing public health interventions to increase physical activity targeting those clusters with low MET.4 18 Similarly, to improve FVI, a targeted population approach should be implemented, for example, controls on advertising, meals and the marketing of fast foods in at-risk areas. Most European countries have controls on advertising directed at children, as does the province of Quebec in Canada.19 Some other examples are Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme to encourage healthy diets in the USA.19

The ICC for MET was moderately correlated with the ICC for FVI. This suggests that the countries that implement a targeted population approach to improve MET should consider simultaneous strategies to improve FVI in those same areas.4

On the face of it, this finding may seem incompatible with what is widely known about the marked differences in the prevalence of obesity (BMI), for example, differences in the BMI in two different countries (South Africa and Vietnam).20 However, it is quite possible to have a rather large average difference in BMI status between two countries and still show a low ICC if the within-area variance of BMI status is sufficiently large. This is precisely the situation revealed by this study, repeated in country after country. It underlines the importance of the issue of within-area heterogeneity of obesity.

Although some of the countries have a low ICC and DE, the general conclusions which can be drawn from this study are that the ICC and DEs are often appreciable, informative and should not be ignored. It is also clear, however, that the DEs may vary substantially among different types of variables and across different countries.21 This requires that public health systems understand how risk factors are distributed within their own populations. The ICC is generally considered to be more generalisable than the design effect, because the latter is dependent on the cluster size. However, an inverse relation between cluster size and the degree of between-cluster variation has been well described.22 Our data, which included a wide range of variables, confirm that the ICCs tend to be larger for smaller clusters. However, the DE will be influenced by the number sampled per cluster, and substantial DEs will result when the number per cluster is large, even if the ICC is small.

The strengths and limitations of cross-sectional analyses of the WHS data have been described a number of times.23 24 The response rate was one limitation; however, it was >60% in all the included countries, except Bangladesh and Ethiopia. This is generally considered low but adequate. The lack of information on non-respondents and exclusion of these non-respondents for weight or height is a limitation of this study. Achieving high response rates in national surveys is always challenging, especially for low-income and middle-income countries.25 Second, in this study, self-reported data on height and weight of the individuals were used. These self-reported measures of BMI in this study might have underestimated the BMI values.26 However, questionnaires and interviews are the standard methods for large-scale data collection, especially in nationally representative surveys for obesity research.26 This study also carries some limitations of secondary data analysis. The WHS questionnaires and the WHS project were not designed specifically for this study. Therefore, data were not available for some important variables of interest. Data for MET and FVI was not available for high-income countries; therefore, the clustering effect for these two variables can only be analysed for low-income and middle-income countries. Data for MET and FVI were not normally distributed. However, with large samples, maximum likelihood estimates are usually robust against mild violations of these assumptions 27; therefore, this approach was used here and the ICC estimates are expected to be valid and reliable.

Conclusion

This study shows that across a wide range of countries, there was low area level clustering for BMI, whereas MET and FVI showed high area level clustering. These results suggested that country level clustering effect should be considered in developing preventive approaches for BMI, improving physical activity and healthy diets for each country.

Footnotes

Contributors: MM contributed to the conceptual framework, data analysis and manuscript writing and DDR contributed to the conceptual framework and write-up.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee granted ethics approval for this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Gulliford MC, Ukoumunne OC, Chinn S. Components of variance and intraclass correlations for the design of community-based surveys and intervention studies: data from the Health Survey for England 1994. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:876–83. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fenn B, Morris SS, Frost C. Do childhood growth indicators in developing countries cluster? Implications for intervention strategies. Public Health Nutr 2004;7:829–34. 10.1079/PHN2004632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guthold R, Ono T, Strong KL et al. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:486–94. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simen-Kapeu A, Kuhle S, Veugelers PJ. Geographic differences in childhood overweight, physical activity, nutrition and neighbourhood facilities: implications for prevention. Can J Public Health 2010;101:128–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masood M, Masood Y, Newton T. Impact of national income and inequality on sugar and caries relationship. Caries Res 2012;46:581–8. 10.1159/000342170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz J, Carey VJ, Zeger SL et al. Estimation of design effects and diarrhea clustering within households and villages. Am J Epidemiol 1993;138:994–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007;370:851–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UN. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/default.htm, 2013.

- 9.Masood M, Reidpath DD. Multi-country health surveys: are the analyses misleading? Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:857–63. 10.1185/03007995.2013.875466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. World Health Survey Reports 2003. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whsresults/en/index.html

- 11.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–504. 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall JN, Moore S, Harper SB et al. Global variability in fruit and vegetable consumption. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:402–9.e5. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan C, Jones K, Moon G. Context, composition and heterogeneity: using multilevel models in health research. Soc Sci Med 1998;46:97–117. 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00148-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser R, Woodruff BA, Bilukha O et al. Using design effects from previous cluster surveys to guide sample size calculation in emergency settings. Disasters 2006;30:199–211. 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2006.00315.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.R-Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In: Computing RFfS, ed. Vienna, Austria, 2012.

- 16.Bartle NC. Is social clustering of obesity due to social contagion or genetic transmission? Am J Public Health 2012;102:7; author reply -8 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barber SL, Gertler PJ. The impact of Mexico's conditional cash transfer programme, Oportunidades, on birthweight. Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:1405–14. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02157.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patnode CD, Lytle LA, Erickson DJ et al. The relative influence of demographic, individual, social, and environmental factors on physical activity among boys and girls. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:79 10.1186/1479-5868-7-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brownell KD, Ludwig DS. The supplemental nutrition assistance program, soda, and USDA policy: who benefits? JAMA 2011;306:1370–1. 10.1001/jama.2011.1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hearst MO, Patnode CD, Sirard JR et al. Multilevel predictors of adolescent physical activity: a longitudinal analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:8 10.1186/1479-5868-9-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day PL, Pearce J. Obesity-promoting food environments and the spatial clustering of food outlets around schools. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:113–21. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corsi DJ, Chow CK, Lear SA et al. Smoking in context: a multilevel analysis of 49,088 communities in Canada. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:601–10. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosseinpoor AR, Stewart Williams JA, Gautam J et al. Socioeconomic inequality in disability among adults: a multicountry study using the World Health Survey. Am J Public Health 2013;103:1278–86. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masood M, Sheiham A, Bernabe E. Household expenditure for dental care in low and middle income countries. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0123075 10.1371/journal.pone.0123075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos Silva ID. Cancer epidemiology : principles and methods. 2nd edn Lyon: I.A.R.C., 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAdams MA, Van Dam RM, Hu FB. Comparison of self-reported and measured BMI as correlates of disease markers in US adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:188–96. 10.1038/oby.2007.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hox JJ. Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. 2nd edn London: Routledge, 2010. [Google Scholar]