Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to understand the influences and decisions of households with children with asthma regarding keeping warm and well at home in winter.

Setting

Community settings in Rotherham and Doncaster, South Yorkshire, UK.

Participants

Individuals from 35 families and 25 health, education and social care staff underwent interview. 5 group interviews were held, 1 with parents (n=20) and 4 with staff (n=25).

Outcome measures

This qualitative study incorporated in-depth, semistructured individual and group interviews, framework analysis and social marketing segmentation techniques.

Results

The research identifies a range of psychological and contextual influences on parents that may inadvertently place a child with asthma at risk of cold, damp and worsening health in a home. Parents have to balance a range of factors to manage fluctuating temperatures, damp conditions and mould. Participants were constantly assessing their family's needs against the resources available to them. Influences, barriers and needs interacted in ways that meant they made ‘trade-offs’ that drove their behaviour regarding the temperature and humidity of the home, including partial self-disconnection from their energy supply. Evidence was also seen of parents lacking knowledge and understanding while working their way through conflicting and confusing information or advice from a range of professionals including health, social care and housing. Pressure on parents was increased when they had to provide help and support for extended family and friends.

Conclusions

The findings illustrate how and why a child with asthma may be at risk of a cold home. A ‘trade-off model’ has been developed as an output of the research to explain the competing demands on families. Messages emerge about the importance of tailored advice and information to families vulnerable to cold-related harm.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides novel insight into the range of psychological and contextual influences that conspire against a low-income household with a child with asthma in keeping warm and well at home.

A ‘trade-off’ conceptual model has been developed to help explain that complexity and how parents balance a range of demands and influences.

The research indicates how health professionals can help a household with a child with asthma, at risk of unsafe winter temperatures and humidity by, for example, referring for interventions in line with the new National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance, raising awareness of the importance of safe home temperatures, and resolving conflicting messages.

As a qualitative study, caution is required regarding transferability of the findings. However, findings were strengthened by the following strategies: recruiting a range of households that offered depth and breadth, conducting the study on two sites, and testing interview findings in group interviews with a range of participants.

Background

Cold, damp housing can have a profound impact on health, as outlined in recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance.1 Attention regarding excess winter deaths and illness has previously focused on older people. However, cold homes are linked to health problems, excess winter deaths and impaired quality of life in other vulnerable households, including those with young children.2–5 Specifically, children living in cold homes are at increased risk of asthma, respiratory infections, mental health problems, low self-esteem, confidence, educational attainment, nutrition, injuries and reduced infant weight gain.2–5

The mental and social impacts of cold homes on children are considerable. School attainment, truancy and bullying are all negatively affected by being in a cold home.6 Overcrowding can occur within a cold home due to ‘special shrink’, the clustering of families in rooms due to limited heating.7 8

Exposure to indoor cold suppresses the immune system and aggravates respiratory conditions.5 Asthma in particular is made worse by cold, damp, poorly heated homes. Asthma is responsible for 1 in 250 deaths worldwide and was the 25th leading cause of disability adjusted life years.9 In addition, asthma accounts for more emergency bed days and emergency admissions to hospital for children and young people than any other paediatric long-term condition.10 The UK has among the highest incidence of paediatric asthma when compared with other countries globally.11 General practitioner (GP) visits for respiratory conditions are estimated to rise by 19% for every 1% drop below 5°C in mean temperature.12 A cold, energy inefficient, poorly ventilated property is more susceptible to the buildup of mould, which is also likely to have negative health impacts on inhabitants, especially respiratory conditions in the young and old.13 14

The negative health impact of being in a cold home is a major public health concern, prompting the launch of the Public Health England Cold Weather Plan and development of NICE guidance.1 13 In this guidance, there is an ongoing call for health professionals to be more engaged in the assessment, identification and referral of those at risk of and vulnerable to cold homes and the associated health impacts.14 However, lack of time, awareness and services to refer into have all been cited as barriers to such engagement.5 14–16

Many people who are in a cold home live in fuel poverty.3 Until 2014, the UK definition for fuel poverty was when households have to spend more than 10% of their income to attain WHO minimum temperature standards (21°C in the living room and 18° in the bedroom). A new fuel poverty definition, ‘Low Income, High Cost’ (LIHC indicator) was adopted in England in line with the 2012 Hills Review.17 This new definition considers a household as fuel poor if fuel costs are above the median level and residual income after subtracting those fuel costs takes the household below the official poverty line. One justification for this change is that the old definition did not capture all those most vulnerable to the impacts of cold homes and fuel poverty and underestimated the problem of fuel poverty for families with children. Using the LIHC measure two-fifths of households classed as fuel poor contain children and one-fifth a child under 5.17 18

Three factors are known to contribute to fuel poverty. These are household income, fuel costs and the energy efficiency of the home. Fuel poverty interventions have traditionally focused on addressing these three dimensions, for example, through benefits and debt advice, social tariffs, and energy efficiency schemes such as Warm Front and the Energy Company Obligation (ECO) component of Green Deal in the 2011 Energy Act for England, Scotland and Wales.19 Some energy efficiency interventions have demonstrated improvements to the health of children with respiratory problems, especially if they include ventilation to prevent mould.20–22

However, research with older people has highlighted that, even if interventions address income, fuel prices and energy efficiency of homes, people may still be at risk of living in a cold home.20 23 The KWILLT study revealed the myriad of factors influencing behaviour regarding keeping warm including attitudes, values and barriers.23 Such knowledge and insight helps us to understand how to identify the vulnerable, what messages about behaviour they will respond to and how to increase uptake of and access to the help they need.

Little is known about the factors influencing behaviour of other groups at risk of being in fuel poverty, in a cold home, and/or vulnerable to negative health impacts. Given the prevalence of paediatric asthma in the UK,11 and the evidence base linking cold damp homes to the exacerbation of respiratory conditions,5 13 14 households with children with asthma are a priority group. The Warm Well Families study is a research project conducted by the authors and funded by Consumer Futures and Doncaster and Rotherham Metropolitan Councils, which aims to address this gap in the evidence by examining the influences and decisions of households with children with asthma regarding keeping warm and well at home in winter. This paper presents findings from the study to enhance health professionals understanding of these influences and reflects on the implications for practice.

Methods

Aim

The Warm Well Families research project aimed to answer the following question: how do parents of children with asthma manage to keep a warm, dry and mould-free home? Qualitative methods were used to capture the views and experiences of adults living in households with children with a diagnosis of asthma and also professionals working with families. The study aimed to generate an accurate understanding of factors that influence keeping warm in the home.

Study approach

We conducted a qualitative study in two stages incorporating first, in-depth, semistructured individual interviews, and second, group interviews. This use of different data collection techniques in each stage allowed us to triangulate findings, expand and verify the data and thus increase the rigour and transferability of the findings. Qualitative methods, using a naturalistic approach, meant the study could generate in-depth understanding of how households made heating decisions in the context of their home environment, acknowledging the influence of wider social determinants on health.24 25 The study was conducted on two sites, Rotherham and Doncaster in South Yorkshire. The areas were chosen as both experience high levels of childhood respiratory illness and related hospital admissions, and fuel poverty6 19 Selecting two areas strengthened the study as it enabled us to include recruitment from a wider population. In addition, Public Health departments in both areas expressed a wish to acquire a better understanding of the links between childhood asthma and a cold home. Both study areas also have substantial quantities of housing stock that are non-traditional, old and energy inefficient. University research ethics and Local Authority approvals were obtained.

Sample and recruitment

Stage 1

In the initial stage, we recruited 35 households with children with asthma and 25 health, education, social care and voluntary sector staff. Our focus was on households vulnerable to cold homes. The intention was not to select households purely on household income level but aimed to encompass wider vulnerabilities. For that reason, we used routine local public health data to identify and focus recruitment in areas with the highest levels of fuel poverty, deprivation, prevalence of childhood asthma and rates of childhood winter respiratory hospital admissions. Households were identified via children's centres, voluntary sector organisations, education welfare officers and parent support advisors. Staff in the recruiting services were asked to identify households with at least one child with a diagnosis of asthma, that is, they had a diagnosis of asthma from their GP and a prescribed inhaler. Households were approached about the study by a service provider known to them. Those who agreed were telephoned by the researcher to arrange the interview. The households who participated in individual interviews included a range in terms of age and number of children, severity of asthma, ethnicity and gender (table 1) and type and tenure of housing (table 1). For each household, one parent was interviewed. Most participants were from low-income households, including those who could not give an accurate estimated income. All households were allocated to one of four income bands based on the benefit eligibility criteria at the time of the study and on the basis of their self-reporting of income (table 1). All participants were at risk of fuel poverty. Sampling, and data collection, continued until no new themes or information emerged from the analysis, that is, data saturation was reached.24 26

Table 1.

Household characteristics

| Participant | Ethnicity/gender of person interviewed | Age | Employment of person interviewed | Employment of partner | Children | Income weekly—less than | Tenure | Type | Insulation | Reported damp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | White British/female | 46 | No | No | 1 | £577 | Privately rented | Semi | Cavity and loft | No |

| 2 | White British/female | 30 | Yes | No | 4 | £379 | Privately owned | Terrace | Cavity and loft | Yes |

| 3 | White British/female | 37 | No | No | 3 | £259 | Rented council | Terrace | Cavity and loft | Yes |

| 4 | White British/female | 29 | Yes | Yes | 2 | £577 | Rented council | Semi | Loft | Yes |

| 5 | White British/female | 29 | No | No | 1 | £259 | Privately rented | Terrace | Loft | No |

| 6 | White British/female | 21 | No | Single parent | 1 | £259 | Rented Private | Terrace | Cavity and loft | No |

| 7 | Pakistani/female | 42 | No | Single parent | 5 | £259 | Privately rented | Terrace | Don't know | yes |

| 8 | Black British/female+male | 42 | Yes | Yes | 2 | £259 | Rented council | Flat | None | Yes |

| 9 | White British/female | 32 | No | Yes | 4 | £379 | Privately owned | Terrace | No | No |

| 10 | Egyptian British/female | ? | No | No | 4 | Doesn't know | Privately owned | Terrace | Loft | Yes |

| 11 | Black British/female | 41 | No | No | 3 | £259 | Privately owned | Terrace | Loft | Yes |

| 12 | White British/female | 36 | No | Single parent | 2 | £259 | Privately owned | Terrace | Loft | Yes |

| 13 | White British/female | 33 | No | Single parent | 2 | £259 | Rented council | Semi | Loft | |

| 14 | White British/female | 46 | Yes | Yes | 2 | £577 | Privately rented | Semi | Loft | Yes |

| 15 | White British/female | 34 | Yes | Yes | 3 | £259 | Privately owned | Terrace | Cavity and loft | No |

| 16 | White British/female | 31 | No | Yes | 2 | £379 | Privately owned | Semi | Loft | Yes |

| 17 | White British/female | 23 | No | Yes | 3 | £259 | Privately rented | Semi | Loft | No |

| 18 | White British/female | 28 | No | No | 2 | £259 | Rented council | Semi | Loft | Yes |

| 19 | White British/female | 28 | No | Single parent | 2 | £535 | Rented council | Flat | Doesn't know and no loft insulation | Yes |

| 20 | White British/female | 42 | No | Single parent | 7 | £774 | Living with relatives | Semi | Cavity and loft | No |

| 21 | White British/female | 27 | Yes | Yes | 2 | £487 | Rented council | Semi | Cavity and loft | Yes |

| 22 | White British/female | 33 | Yes | Yes | 2 | Didn't know | Privately rented | Semi | None | No |

| 23 | White British/female | 29 | Yes | Yes | 3 | £769 | Privately owned | Mid-townhouse | Cavity and loft | No |

| 24 | White British/female | 30 | Yes | Yes | 4 | £600 | Privately rented | Semi | None | Yes |

| 25 | White British/female | 44 | Yes | Single parent | 3 | £280 | Rented council | Terrace | Cavity and doesn't know | Yes |

| 26 | South Asian/female | 38 | Yes | Yes | 3 | £325 | Privately owned | Detached Victorian | Cavity and loft | No |

| 27 | Saudi Arabian/female | 27 | Yes | Yes | 2 | £577 | Privately owned | Semi | Cavity and loft | No |

| 28 | White British/female | 40 | Yes | Yes | 1 | £325 | Rented council | End terrace | Cavity and loft | Yes |

| 29 | White British/female | 27 | Yes | Yes | 1 | £625 | Privately owned | Semi | Cavity and loft | No |

| 30 | White British/female | 33 | Yes | Yes | 1 | £575 | Privately owned | Semi | Cavity and loft | Yes |

| 31 | White British/female | 18 | No | Single parent | 1 | £220+housing and council tax benefit | Privately rented | Semi | Doesn't know and Loft | Yes |

| 32 | White British/female | 44 | No | Single parent | 2 | £200 | Rented housing association | Semi | Doesn't know and Loft | No |

| 33 | White British/female | 38 | Yes | Yes | 2 | £1604 | Privately owned | Semi | Cavity and part Loft | Yes |

| 34 | White British/female | 32 | Yes | Yes | 2 | £600 | Privately owned | End terrace | Cavity and Loft | No |

| 35 | White British/female | 27 | No | Yes | 3 | £200+council tax benefit | Privately rented | Mid-terrace | Doesn't know | Yes |

As a gesture of gratitude, participating households were given a ‘Warm Pack’ with a few simple items such as a fleece blanket, hand warmers, room thermometers, etc, alongside a £15 high street voucher. Where required, after the interview, parents were also signposted to organisations for help and advice regarding, for example, energy advice, smoking cessation and housing advice.

Health, education and social care professionals were recruited from National Health Service (NHS), Local Authority and the community and voluntary sector organisations. They were contacted via email or phone through their employing organisations. The recruitment criterion was that they were involved at a strategic or practice level in the delivery of care, education or support for children and/or parents.

Staff (n=25) who participated in individual interviews represented a range of roles from health professionals (3), police and emergency services (3), Local Authority Children and Young People's Services (8), Local Authority other (3) and Voluntary and Community Sector (8).

Stage 2

Following initial analysis of the stage 1 interviews, group interviews were used to challenge, verify and expand on these findings. Five group interviews were held in total. Four groups with staff (n=25) including people from a range of organisations, police and emergency services (2); Local Authority Children and Young People's Services (5); Local Authority other (14); Voluntary and Community Sector (1) and other organisations (3). Participants of the staff group interviews were not the same as those who participated in the individual interviews.

One group was held with parents from a children's centre (n=20). Recruitment for parents was conducted via the children's centre. Staff were contacted by email. Box 1 gives a summary of the professional interview and professional focus group participant characteristics.

Box 1. Staff participants—interviews and focus groups.

Staff role and organisation

Staff individual interviews (n=25)

Health professionals

▸ Asthma Nurse

▸ Health Visitor×2

Police and Emergency services

▸ South Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Service—Community Liaison Officer

▸ Police Support Officer×2

Local Authority—Children and Young Peoples Services

▸ Parent Support Advisor×2

▸ Children Centre Manager

▸ Children Support Worker×2

▸ Healthy Schools Coordinator

▸ Education Welfare Officer

▸ Head Teacher

Local Authority—other

▸ Gypsy and Traveller Worker

▸ Safer Neighbourhood Officer

▸ Elected Member

Voluntary and Community Sector

▸ Citizens Advice Bureau Worker×3

▸ Finance worker ×3

▸ Home Improvement Agency Support Worker

▸ Home Improvement Agency Manager

Staff group interviews (n=25)

Police and Emergency services

▸ Vulnerable Persons Advocate ×2

Local Authority—Children and Young Peoples Services

▸ Education Welfare×2

▸ Child Protection Officer

▸ Children Centre Manager

▸ Children Centre Support Officer

Local Authority—other

▸ Financial Inclusion manager

▸ Private Sector Housing Officer

▸ Contracts Manager

▸ Environmental Health Officer

▸ Senior Energy Advisor

▸ Council Housing Officer

▸ Well Being Officer

▸ Wider Determinants Manager

▸ Health and Wellbeing team worker

▸ Community Safety Officer

▸ Community Support Officer

▸ Health and Social Care Team member

▸ Area Team representative,

▸ Active Doncaster Support Officer

Other

▸ Council Maintenance manager

▸ Pensions Officer

▸ ‘Business Doncaster’ representative

Voluntary sector

▸ Fuel poverty project worker

Data collection

All data were collected between December 2012 and June 2013. Individual interviews took place with the parents of the recruited households, in their home. Where required, an interpreter was present. Consent was obtained prior to the interview which was digitally recorded. Interviews were semistructured and lasted between 20 and 60 min. Interviews were guided by an interview schedule. The schedule was informed by the related literature and policy, and prior experience of the KWILLT project.20 Questions fell into the following broad areas: knowledge regarding temperature and health, values and beliefs regarding safe and healthy temperatures, affordability of heating and fuel payments, and sources of help and advice.

Groups took place in work venues for staff and the children's centre for parents. Study information was given to potential participants by those recruiting in both verbal and written format. Prior to the group interview and consent being obtained, further information was provided by the researcher and a discussion held regarding participation. A topic guide was used to guide the discussion. The topic guide covered the same areas as the individual interviews and findings emerging from the interviews. Two members of the research team attended each focus group, one to facilitate and one to scribe. They were also digitally recorded. Individual and group interview data were transcribed in full and any identifying data removed. Transcripts and field notes were entered onto NVivo V.10 software.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using a framework analysis approach.24 27 NVivo V.10 was used to facilitate this. All the interviews were initially analysed by one of four researchers (ACdC, VP-H, CH and PN). One of the other researchers from the team then independently analysed transcripts to verify interpretation (AMT and AS). Following the initial individual interviews, a provisional thematic framework was developed after the core researchers (ACdC, VP-H, CH and PN) had familiarised themselves with the data and discussed them with the wider team. Analysis then involved the following stages and techniques: indexing transcripts by applying codes to data, then generating coding charts, memos and reports, to aide mapping and interpretation. Following each stage of the study, the new data were included for analysis to challenge and expand on the existing thematic framework. Regular team discussions were held where consensus on the thematic framework was generated through negotiation. The final thematic framework outlined the contextual, social, psychological and attitudinal factors influencing parent’s heating decisions.

As with the earlier KWILLT study,20 in the second stage of analysis, the themes and data on factors influencing behaviour were reviewed to identify how the factors combine to create risk for different groups of people. From this, a ‘segmentation model’ was developed that described four ‘subgroups’ of households with children with asthma at risk of the negative health impact of cold weather because of contextual and psychosocial factors. This segmentation model was used to develop pen portraits and a ‘trade-off’ model.

Segmentation is a way of looking at the population of concern and identifying distinct subgroups or segments with similar characteristics, situations, needs, attitudes or behaviour.28 29 This helps us to understand why certain groups may behave in a particular way and increase their risk of ill health or harm. Segmentation techniques developed from marketing theory. Previously segmentation approaches have been criticised as overly relying on descriptive factors of consumers and not being an efficient predictor of future behaviour.30 For example, segmentation based on demographic data alone ignores beliefs and attitudes which influence behaviour. We used segmentation within a ‘social marketing’ approach.28 29 Social marketing aims to develop activities and interventions to change, maintain and encourage behaviour within both individuals and society, in this case behaviour related to keeping warm and well at home. As such, attitudinal and psychological factors combined with contextual and social factors are used to define segments of the population at risk of being cold at home. There is reasonable evidence that interventions in health and social care based on segmentation and using social marketing principles can be effective.31

For this stage, a series of research team meetings were held to review the thematic framework and underpinning data. Diagrams, charts and matrices were developed to aid interpretation. Factors and items that influenced behaviour were clustered together and mapped out to identify key drivers and influences of behaviour and then compared back to the original data for verification. Key findings that informed the development of the pen portraits, segmentation and ‘trade-off’ models are presented in the following section.

Findings

The different data revealed a range of influences which explain the complex world within which families operate and the barriers they encounter in relation to keeping warm. They indicate that households have to carefully balance and manage the various pressures, demands and barriers they encounter in trying to control home temperature and humidity for the health of their child. The findings are presented here using the following headings of households, staff and finally, the segmentation and ‘trade-off’ models.

Illustrative quotes from the data are provided from the households (boxes 2 and 3) and staff (box 3) data in order to elucidate the findings reported here.

Box 2. Illustrative quotes from household interviews.

Cold, damp and mould

“He wakes up and he'll come and wake me up and mummy I'm cold, I'm cold, and you can hear it on his chest. So the warmer he is, the better he is”. (P13)

“When it gets too hot, have to turn the radiator off because the air dries out and they start coughing”. (P5)

“The bathroom's covered in it, I've got damp all along that back wall behind you, all along that wall. Get black mould up in my daughter's bedroom, it's everywhere.” (P4)

Knowledge and awareness

“‘It was a lot worse, and his eczema flared up as well, so he had the eczema and asthma at the same time, and it was like, it scared him because I mean seeing his eczema flared and they also, because he was wheezy all the time, he couldn't contemplate, and then as soon as we got rid of the damp, it just went down straight away”. (P13)

“No. I don't have his window open in summer because of the pollen…Yeah because it clings to his bedding and that I've been told to keep his window shut. So it does get a bit stuffy in his bedroom and if I know he's sleeping out I'll open his window until it ventilates and then wash his bedding, you know, so there's nothing clung to it. But I mean everybody else's windows they're open, you know, I just don't open his.” (P21)

Competing priorities

“I wouldn't put it above my mortgage. The reason why is because I feel like if you can't pay for your mortgage your not going to be having gas anyway or electricity.” (P23)

Fear and control

“It's got to be my electric and gas. That's the first thing that comes out of my money on a Tuesday morning…You know that you've got that amount of money to last you a week and you've got a massive chunk that's coming out, that's going on gas and electric, and then you've got your food on top of that…it is hard, really hard.” (p3)

“It's too expensive to run that. I think I put it on last winter while it was snowing and I only put it on for an hour each night and my bill went up like £150 that month.” (P5)

“Yeah it's on the boiler and I just, you push it up or down…I've got to traipse upstairs every time I want it on or hot water.” (P6)

“No it's not on in the morning. It's freezing in the morning but it's not worth you know like having it on for the 10, 15 minutes they're up.” (P19)

Self-disconnection

“We've got to literally manage everything. Everything has to be written down what we're spending, how much is going here, how much is going there.” (P3)

“We don't go in there in the winter because it's freezing; it's too cold…even with the central heating on…” (P3)

“I put the heating on for her but sometimes I have to tell her to wrap up…It's because I cannot always afford it, that meter eats my money up like crazy.” (P18)

Family and friends

“Sometimes we go to my mums, she makes our tea for us too ‘cos she knows I can't always afford to go to the supermarket…and my daughter has a bath.” (P18)

“So what we do sometimes is I'll, when I've got the money I'll lend her it, so then when I'm skint she can give it me back. So that helps quite all right as well.” (P5)

“I wouldn't ask any of my friends. There'd only really be my mum I'd ask but like I say she'd lend it to me but she wouldn't have any money herself so I wouldn't ask her, I'd just try and sort it myself to be honest. I wouldn't ask anybody.” (P21)

Box 3. Staff, segmentation and “trade-off” illustrative quotes.

Staff

Cold, damp and mould

“Well generally I've been in houses that have been very cold, sometimes quite damp…Recently I had a family that had a wooden cot for their new baby but before the baby was born they had to throw the cot out because it was so damp and had mildew on it.” Health visitor

Knowledge and awareness

“If you open all the windows in summer you can let in all the allergens that cause hay fever and can make asthma worse.” Asthma nurse

Fear and control

“I think that's probably the hardest group to access, the ones who are in need but are hiding it. And the children will be probably going to school regularly, and they'll do everything not to draw attention to themselves and just look like everything is OK on the surface.” School and family support worker

Competing priorities

“And I have parents who choose between putting £10 on the gas meter or sending their children to school, and they choose to heat the house, so they don't send the children to school. They're not able to use the cooker either with no gas, so they'll put the gas on rather than send the children to school with the bus fares and dinner monies.” School and family support worker

Responsibility

“I think it comes down to when they prioritise what they spend the money on. Obviously people do want to heat the house, but from my experience of having visited and when they've got say £70 a week and they've got to pay the rent and they've got to feed themselves and they may have children, they do tend to put heating as a lower priority.” Financial Inclusion Officer

“But out of the bulk of the calls, 80%, 90% of them are condensation and as such it's trying to educate the tenant that they do need to keep the heating on as background heat and they don't need to put clothes on the radiators, they do need ventilation.” Local Authority Officer

Family and friends

“I think it often depends on what support they have, thinking of family and friends, because at the moment even this week we went to see a lady, she was out but because she's just moved into this house and she has no heating, no beds, no fridge, no cooker, and it didn't surprise me that she wasn't in., because if she's got some support somewhere else then families tend to go out when they can.” Health visitor

Segmentation: context factors

“Then winter comes again and it all happens again isn't it? I mean in winter all wall in my bedroom will be black mouldy again, wall in passage will all be black mouldy again (daughter's) will be black mouldy again, but all you get off them is its condensation. So you can't win.” (P28)

Segmentation: psychological factors

“I know it can work out cheaper if you do it by direct debit, but I just think to myself if there ever comes a time when I didn't have the money or haven't got the money, I couldn't cope with getting these few hundred pound bills coming through and having to pay it, I just couldn't do it, I couldn't pay it, I know I couldn't. I like to know what I've put on is what I've got.” (P30)

Households

Cold, damp and mould

The data from parents indicated that cold, damp and mould were seen as significant problems by household members. Damp and mould were prevalent in the homes of participants that were cold, poorly heated and poorly ventilated. Participants reported experience that cold temperatures impacted on the health and well-being of both children with asthma and others in the home. However, a smaller number of families identified excessive heat as a trigger.

Knowledge and awareness

Households varied in their knowledge and behaviours of heating and health, including impact on asthma. Most had little knowledge about safe temperatures and avoiding asthma triggers. There were a small number of examples where knowledge had prompted action and a health benefit, most noticeably in relation to the control of damp.

Further, a small number reported awareness that air quality and mould were triggers of asthma. In addition, a few respondents were able to identify that keeping the house at an even temperature was important. However, most lacked knowledge about asthma and temperature. The range of support and sources of information varied across participants but there were examples where information had been obtained from the GP surgery or asthma nurse. However, sometimes this conflicted with information given by other professionals. Households explained how they had to navigate through these conflicting messages. A key example regarding cold and mould related to ventilation. Housing advice was to open windows and ventilate property to maintain air quality and avoid mould. However, this sat alongside advice from health professionals advising people to close windows to avoid exposure to allergens that would trigger asthma. In addition, police advice was to keep windows closed for personal safety.

Competing priorities

Fuel and thermal comfort were prioritised in household expenditure. However, due to competing priorities difficult decisions were made by participants. So while heating was one of the most important household priorities, the most important was keeping a roof over the families head.

Participants explained that the rent or mortgage were priorities first. Fuel came next, alongside other priorities such as food, transport to school and work, and clothing. These competing priorities meant heating was rationed. While a few left their heating on for most of the day, most participants limited their fuel use and prioritised times when the children were home. “If we are going out at 9 I don't put it on it’s not worth it.”

Fear and control

All of the interviewees were on a low income, whether unemployed or in low paid employment. For all there appeared a pervasive fear of debt, of ‘not managing’, and of ‘getting behind’. Participants described how high bills were to be avoided at all costs. This fear of debt and of wanting to be in control led to some families choosing to pay for fuel on a prepayment meter, even though they knew that method was more expensive. However, the meter allowed them to control their fuel usage and avoid large bills.

Participants did not often feel in control of their heating or how much it cost. There was therefore an inter-relation between fear and control of heating systems, equipment and patterns of heating use. Where there was no thermostatic control or timer, it seemed easier and cheaper not to use the heating at all or to engage in energy inefficient stop/start patterns of heating. The latter resulted in peaks and troughs of home temperature. For example, many did not put the heating on in the morning before leaving for work or school.

Thus, fear and lack of control contributed to a practise of self-disconnection in an attempt to manage limited household budgets.

Self-disconnection

Disconnection by an energy company was seen by households as something that must be avoided but self-disconnection was reported as a regular feature of life. Use of heating was therefore balanced and managed in the complex interplay between low income, high fuel bills, household priorities and child health and well-being.

Different degrees of self-disconnection were evident from participant's experiences, for example, not heating particular rooms at all, not heating particular rooms at specific times (eg, in the mornings before school) and not heating the house at all. Other strategies were employed alongside self-disconnection in an attempt to balance heating with other priorities. The most common strategy was wearing more clothes in the home.

Despite a lack of knowledge about cold, mould and health, many parents managed the best they could with the limited household income. They displayed remarkable budgetary skills and made difficult judgements regarding household priorities.

Family and friends

Families were seen, not only to manage their own household resources, but to also provide help and support for extended family and friends. In return, they also turned to peers and family for support and advice. Three patterns of behaviour were identified from the data. First, if a household could not afford to heat their home, they would call round, or spend time with relatives or friends who were in a slightly better financial position. Second, money was sometimes loaned and moved around family members or between friends, according to who was better off that day or week. Third where a household was isolated from friends and family, whether geographically or socially, or they did not want to ask individuals who were seen to be in a similar financial position to themselves, support was harder to access. They would do without rather than ask for help because of the burden a request would place on others.

Staff

The findings from the staff interviews and focus groups resonated with those from households. However, there were differences in how household behaviours were understood and explained. The majority of professionals emphasised the importance of individual responsibility (box 3). They saw the householder and parent as solely responsible for their behaviour and the consequences in terms of property condition and child health. Professionals did not always acknowledge or were not aware of the challenging balancing act households conducted in managing low income, high fuel bills and other household priorities. Staff who emphasised individual responsibility thought the best way to help households was to provide advice on household capability and budgeting. However, the household interviews demonstrated participants were managing their budget well considering the financial limitations. A smaller number of staff blamed the wider structural constraints experienced by households and referred to recent government policy, rising fuel costs, complex payment methods and tarrifs, and competing household priorities as more important influences.

Segmentation and ‘trade-off’ models

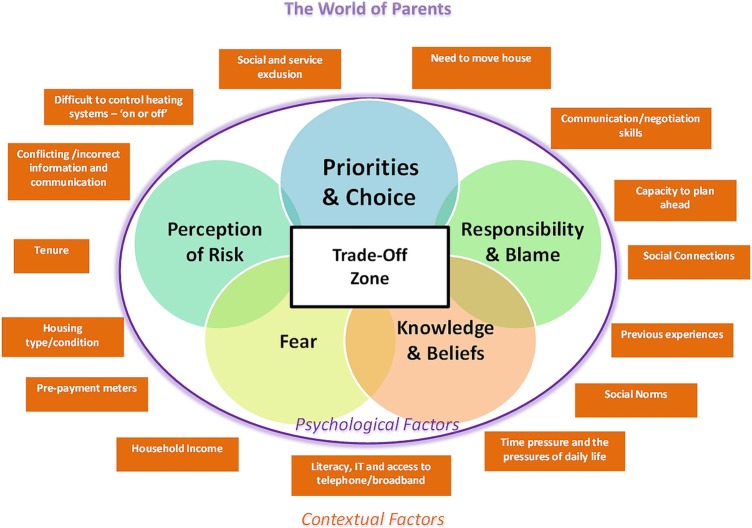

The findings indicate that a range of contextual factors can lead to cold and damp homes. For example, the type of home, tenure, the condition and energy efficiency of a home, the type of heating and household income (table 1). These are joined by social factors such as the nature and quality of social contact and support from friends and family, alongside social and health services (boxes 2 and 3).

Interacting with the contextual factors were psychological factors which can lead to damp and cold in the home. For example, the behaviours and coping strategies families employ to keep warm and manage household budgets based on knowledge and awareness of cold household temperatures, heating systems, getting help and trusted sources of information. They were also influenced by attitudes and beliefs, including fear of debt, priorities and beliefs regarding asthma, cold and health. The contextual factors interacted with the psychological factors as families ‘juggle’ or manage priorities against resources in an attempt to keep warm and well at home.

This ‘juggling’ of priorities against resources often meant the parents were making ‘trade-offs’ (figure 1 and box 3). For example, as explained above, a high percentage of the families interviewed paid for their electric and gas through prepayment meters. The parents knew this was an expensive way to pay for their fuel. However, a fear of debt, large bills and of not managing was expressed by many of the participants. In this instance, the trade-off was higher fuel prices versus fear of debt and the ability to control large bills coming in through controlling their fuel usage and if required self-disconnection. The trade-off is therefore driven by fear of debt.

Figure 1.

The trade-off zone. The model represents some of the contextual and psychological factors found in the research and aims to help professionals understand how similar challenges may lead to different behaviour outcomes within different families.

To demonstrate the complex interactions of psychosocial and contextual influences on the parents, a segmentation model (table 2) and ‘trade-off’ model (figure 1) were developed. These form the basis of a series of four pen portraits that illustrate how the different factors can come together to drive behaviour and inadvertently place a child at risk of a cold home or exacerbation of their asthma. A précis of one pen portrait is provided in box 4.

Table 2.

The segmentation model

| Pen Portrait | The segment | Emotional and psychosocial factors | Contextual factors | What this means to behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paula and Steve | Seeing the issue and overcoming barriers | Pride, family values. Social norms of making ends meet and saving a little | Housing and tenure, family and social support, ability to access services and technology | Able to take action and address problems/overcome barriers |

| Michelle and Ryan | Constantly juggling | Anxiety and reluctance to contact landlord, fear of losing home | House needs repairs, shift work and need for child care | Try to juggle life and manage everything themselves |

| Clare | Just living day to day | Social norms—behaviour influenced by these around them as they see things such as coping day-to-day as the ‘norm’ | Household income | Exclusion from services, does not access help |

| Adam and Steph | On the edge of crisis | Fear, shame, blame and responsibility | Household income, housing conditions and tenure, service exclusion | Self-disconnection, no quality time as a family, becoming withdrawn and depressed |

Box 4. Pen Portrait Adam and Steph—segment, on the edge of crisis.

1. About Adam, Steph and their children

Adam and Steph own their own home and are not in regular contact with services. They are really struggling with normal day-to-day life, worried how much longer they can cope and are afraid of what might happen to their family. At the moment they are both out of work and are managing on unemployment benefits.

They are unable to ensure their home is in good repair and cannot heat the house properly which means that it is often cold and damp in most of the rooms. This is affecting the family's health. Both their boys have had bad chests and their oldest son has been ill a lot. The doctor has now said that he has developed asthma and has been to A&E department twice because of this. Their son regularly coughs all night, waking frequently and making it difficult for the family to sleep. His asthma is worse in the winter and they worry as the colder weather draws in.

Since leaving their parents homes, they are not known to any support services and to those outside the family; they appear to be ‘managing’.

They need to ‘juggle’ or manage priorities against resources which often means they are pushed into what we have called a ‘trade-off’ zone. These ‘trade-offs’ drive behaviour and, in conjunction with Adam and Steph's ability to take action when faced with a specific set of circumstances or challenges, will ultimately govern the level of vulnerability for their children.

Adam and Steph are overwhelmed with the struggle of daily living. At the moment it is unlikely that they will be able to take any proactive changes without help. They do not know how to get out of the current cycle and are pinning all their hopes on Adam being able to find another job. Steph has lost all confidence and as much as she wants Adam to get a job, she is also afraid of being on her own with the children all day. The family's health is deteriorating and Adam and Steph cannot see a way out.

| Housing | Heating | Method of payment | Ethnicity | Age | Employment | Children | Income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privately owned semi detached | Gas CH Electric fire |

Prepayment meter | White British | Early 20s | None | 2 children 3 years 5 months |

Unemployment benefit only |

2. Factors that drive Adam and Steph into the trade-off zone and influence their decisions and behaviour

Primary drivers of behaviour

Household income

Housing conditions and tenure

Fear and shame

Additional drivers of behaviour

Lack of social connections and family support

Service exclusion

Responsibility and blame

3. What are the best ways to identify people like Adam and Steph?

| The segment | Contextual factors | Emotional and psychological factors | What this means to behaviour | How this impacts on their children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On the edge of crisis | Household income–unemployment benefit Service exclusion–only see general practitioner (GP) and nursery staff Housing conditions and tenure–own home but in very poor state of repair |

Fear—that they will lose their children if they cannot care for them properly Responsibility and blame—they want to provide a good family home but feel to blame for how they are living now Embarrassment and shame—worried how others will see them, that they will be judged by authority/services Lack of social connections and family support—no one to turn to or offer help |

They are not seeking help from services They are making trade-offs that are affecting their health and well-being They are becoming ‘trapped’ in this cycle of struggle They are becoming more isolated |

Health and well-being is beginning to be detrimentally affected |

4. How can we help Adam and Steph

| Adam and Steph | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| What might the interventions be? | Where/how do we talk with them? | What are the barriers? | What are the key messages for professionals? |

| A trusted contact to offer support and sign-posting. They must be able to relate to these people—none authoritarian and threatening. Possible peer support. Reliable and simple information accessible through appropriate channels of communication Means to access channels of communication Back to work advice and courses A mechanism to reduce isolation and gain a support network |

Many young couples/mums will get help and advice from friends and family. They will often use social media as a means of communication. Adam and Steph are restricted in their ability to utilise these channels and therefore feel alone and have poor knowledge of their entitlements In order to begin engagement and support we could consider—the GP and the nursery staff. Mother and toddler groups where there might be people in similar situations as Steph Peer support through informal groups—advertised through GP, nursery or local free papers/radio. Messages MUST contain information on HOW to access the help and WHERE to get support |

Feeling of failure Mistrust of services Fear of losing family/independence |

Cold has a serious impact on health. Not just physically but it can also lead to depression and isolation for adults Living in a cold home has a detrimental impact on child development and school readiness Don't assume people are coping Multiple factors can drive behaviour—not just lack of money or knowledge There is help out there—get to know your local referral schemes Don't underestimate the power of the psychological factors such as fear, blame and shame |

Discussion

This is the first in-depth study to understand the complex environment within which parents make decisions about household temperature, focusing on a population at risk of cold-related harm; households with children with asthma. The findings of this study resonate with other research that focuses on the impact and experience of fuel poverty for children. As with previous research, households in this study described how cold and damp impacted on their physical and mental well-being.2–4 This study builds on existing evidence2–3 and establishes that struggling to heat the home can have a profound impact on health, in this case respiratory health. It adds to existing evidence by revealing how limited finance and challenging home environments can negatively impact on mood, and psychological health. Lack of control and fear emerged as key factors for Warm Well Families participants in influencing their psychological well-being.

The competing financial priorities within households is highlighted in these findings, as in other studies.32–34 However, the Warm Well Families study reveals a situation more complex than ‘heat or eat’ and exposes the multiplicity of trade-offs families have to make. The sample in this study included a mix of households who were unemployed and on low incomes. The study reflects the findings of Liddell2 in that, for low-income households, employment offered little protection against the threat of a cold home and the reality of struggling to keep a family warm.

The findings reveal how parents were constantly assessing their family's needs against the resources available to them. Many of the parents interviewed displayed high levels of ability and skills in the way they controlled, managed and allocated limited budgets and planned ahead for expenditure. Evidence was seen of parents working their way through conflicting and confusing information or advice, negotiating with professionals and taking different approaches when faced with barriers in the way of what they wanted to achieve. Parents were also seen, not only to manage their own time and resources, but also provide help and support for extended family and friends. In return, they also turned to peers and family for support and advice. Where a household was isolated from family and friends, support was lacking.

The majority of previous fuel poverty and health studies have focused on multigenerations or older people and not specifically on children and families.3 20 While there are some universal themes coming from these studies they do not give us enough information to know what health risks children and families are facing, how fuel poverty is played out in families or what interventions might be most effective in protecting families from cold homes. Some clear differences between older people and families have emerged from this study and which match those of previous research.32–35 Examples include the fact that young families tend to be more transient in housing, face different challenges with income, have more people in the house with conflicting levels of thermal comfort, and have different behavioural influences because of differences in experience and beliefs between generations.2 22

This study added new insight, primarily in understanding the many and varied influences and the manner of the trade-offs people have to make on a limited income. It did appear that heating was a valued priority, but second to keeping a roof over their heads. This meant heating vied against equally urgent household demands.

The findings indicate that it is important for professionals not to make assumptions about why people make the decisions they do make. The key example here is that some health professionals assumed people were lacking budgetary management skills and thought interventions should be directed in this area. In this study, the participants were excellent budgetary managers. It was the lack of monetary resources, combined with their underlying attitudes and values that drove behaviour. This means financial interventions that focus on budgetary management may be misplaced. However, financial interventions aimed at increasing household income by supporting return to work or unlocking unclaimed benefits may be very helpful. This study supports recent claims that often those inappropriately judged as financially incapable are in fact poor. Being able to make ends meet in poverty requires environmental and social change, not just budget advice.36

It did appear that more could be done to increase awareness of the importance of heating and how to avoid damp and mould. Increasing the amount of targeted, accessible, easy to understand and accurate information to different segments of people at risk may help. The findings indicated that parents of children with asthma were working on conflicting knowledge, gained from a range of sources, but ultimately difficult decisions were made to try and act in the perceived best interests of the family. Consequently, it is important for health and social care professionals to understand the trade-offs families make. Examples include trading-off adequate ventilation and the consequent damp and mould against conserving heat and saving money, or a family trading-off an open window against household security. For health professionals caring for children with asthma, it emerged as particularly important to reduce the amount of conflicting information to parents delivered across professional groups, for example, health, housing and police. In our study, parents were left confused by this conflicting advice. Improved communication may also help make heating a higher priority for households with children with asthma.

The NICE guidance highlights the importance of a health professional contribution to identifying people at risk and providing information, advice and appropriate referral.1 The guidance to GPs on cold homes is not without challenge in the context of increased bureaucracy and a blurring of boundaries between health and social care roles. Furthermore, it may not be obvious who is at risk of cold-related harm because people are good managers and the trade-offs made can make vulnerability invisible. How professionals understand and explain family behaviour influences both the type and manner of the support they offer. The indication here is that the values and belief systems of health and social care professionals about poverty and individual responsibility can be as important and influential as knowledge about cold homes and can impact on health in how messages are conveyed and services provided. Interprofessional training may resolve conflicting messages regarding cold homes, but the delivery and access to such training has practical barriers when training requirements for professionals are so demanding. However, further research could evaluate the impact of accessible training solutions, such as e-learning packages.

The limitations of the study are that, as with many fuel poverty studies, it was hard to find families actually exposed to cold homes because trade-offs were made in other areas of family life to be able to provide heating. However, these trade-offs are an important part of understanding how fuel poverty can impact on health on a wider scale than just exposure to cold. The study also focused only on families with a child with asthma, while there are multiple conditions affected by cold and damp homes. This focus on a subgroup of a wider at risk population makes any broad generalisation from the findings difficult. In addition, the sample was recruited through social care settings with the potential that those vulnerable but not in contact with services were omitted. Similarly, the participants in this study were primarily white British. The sample did match the demographic of the study centres but the lack of ethnic diversity would inhibit wider transferability. More evidence and insight is required to understand the differences and similarities effecting different ethnic populations with regard to fuel poverty, cold homes and health. Further research is also required to examine the impact of fuel poverty, energy price rises and welfare reform on the health of different segments of the population.

Conclusion

This project has generated findings to help people working in public health, policy and practice understand the complex network of factors that influence how households make decisions regarding keeping warm at home. The findings illustrate how and why a child with asthma may be at risk of a cold home. It identifies that parents are often trying to follow conflicting advice or balancing impossible financial demands.

The segmentation and ‘trade-off’ models that have been developed explain the competing demands on families, the decisions they make and why certain groups may behave in a particular way which unintentionally increases their risk of ill health or harm. Messages emerge from the research about the importance of tailored advice and information to families vulnerable to cold-related harm which the trade-off model and pen portraits based on the segmentation analysis seek to inform.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank the following for funding elements of the study: Consumer Focus, Doncaster Primary Care Trust, Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council Rotherham Primary Care Trust, and Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council. They are also grateful to the following organisations for their help in the study, especially for recruitment of participants: Doncaster Children Centres, Green Gables, Grow, Rotherham Education Welfare and Parent Support Advisers. They would like to thank especially the participants of the study. They are very grateful to all the participants for their willingness to share their experiences and views.

Footnotes

Contributors: The article is based on a project designed by AMT, PN, CH and AS. Data was collected mainly by ACdC, VP-H, CH and PN, supported by AMT and AS. All authors contributed to the analysis but was led by ACdC, VP-H, CH and PN. AS led the development of the segmentation and ‘trade-off’ models. AMT and PN produced the final draft of the paper but all authors commented and contributed to the earlier drafts.

Funding: Consumer Focus, Doncaster Primary Care Trust, Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council, Rotherham Primary Care Trust, and Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from Sheffield Hallam University Research Ethics Committee (Faculty of Health and Wellbeing).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Anonymised data will be made available on request to the corresponding author at angela.tod@manchester.ac.uk.

Research reporting checklist: The COREQ (Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research) was used to check the quality of the paper prior to submission.

References

- 1.NICE Guidelines. Excess winter deaths and morbidity and the health risks associated with cold homes 2015. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng6 (accessed May 2015).

- 2.Liddell C. ‘Policy briefing—the impact of fuel poverty on children’. Belfast: Ulster University & Save the Children, 2008. http://tinyurl.com/STC-Policy-Briefing-FP (accessed May 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot Review Team. The health impacts of cold homes and fuel poverty. London: Friends of the Earth, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Children's Bureau. Fuel poverty and child health and wellbeing 2012. http://www.ncb.org.uk/media/757610/ebr_fuel_poverty_briefing_20june.pdf (accessed May 2015).

- 5.Public Health England. Cold weather plan for Engla nd. Making the case: why long-term strategic planning for cold weather is essential to health and wellbeing London: Public Health England, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes M, Butt S, Tomaszewski W. The dynamics of bad housing: the impact of bad housing on the living standards of children. London: National Centre for Social Research, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrell C, McAvoy H, Wilde J. Tackling health inequalities: an all-Ireland approach to social determinants. Dublin: Combat Poverty Agency, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawlor DA, Maxwell R, Wheeler BW. Rurality, deprivation, and excess winter mortality: an ecological study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:373–4. 10.1136/jech.56.5.373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S et al. For the Global Initiative for Asthma (2004) Global Burden of Asthma. http://www.ginasthma.org/pdf/GINABurdenReport.pdf (accessed May 2015).

- 10.Yorkshire and Humber Public Health Observatory. Asthma Primary Care Trust Summary: Regional Summary http://www.yhpho.org.uk/default.aspx?RID=136388 (accessed May 2015).

- 11.Global Asthma Network. Global Asthma Report 2014. http://www.globalasthmanetwork.org/publications/Global_Asthma_Report_2014.pdf (accessed May 2015).

- 12.Hajat S, Kovats RS, Lachowycz K. Heat-related and cold-related deaths in England and Wales: who is at risk? Occup Environ Med 2007;64:93–100. 10.1136/oem.2006.029017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kmietowicz Z. Public Health England. Cold weather plan for England. London: Public Health England, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kmietowicz Z. GPs should identify and visit people at risk from cold homes, says NICE. BMJ 2015;350:h1183 10.1136/bmj.h1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCartney M. Margaret McCartney: Can doctors fix cold homes? BMJ 2015;350:h1595 10.1136/bmj.h1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UK Health Forum. Putting health at the heart of fuel poverty strategies: Event Report 2013. http://nhfshare.heartforum.org.uk/RMAssets/UKHF_Events/2014/Event%20report%20-%20health%20and%20fuel%20poverty%20evidence%20summit%2020%20Nov%202013.pdf (accessed May 2015).

- 17.Hills J. Getting the measure of fuel poverty. London: The Department of Energy and Climate Change, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Save The Children Rising energy costs: the impact on low income families. London: Save The Children, 2012. http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/sites/default/files/docs/Rising%20energy%20costs%20briefing.pdf (accessed May 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 19.UK National Archives. The Energy Act 2011. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2011/16/contents/enacted (accessed May 2015).

- 20.Howden-Chapman P, Matheson A, Crane J. et al. Effects of insulating existing houses on health inequality: cluster randomised study in the community BMJ 2007;334:460 10.1136/bmj.39070.573032.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards RT, Neal RD, Linck P et al. Enhancing ventilation in homes of children with asthma: cost-effectiveness study alongside randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e733–41. 10.3399/bjgp11X606645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Somerville M, Mackenzie I, Owen P et al. Housing and health: does installing heating in their homes improve the health of children with asthma? Public Health 2000;114:434–9. 10.1038/sj.ph.1900687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tod AM, Lusambili A, Homer C. et al. Understanding factors influencing vulnerable older people keeping warm and well in winter: a qualitative study using social marketing techniques. BMJ Open 2012;2:pii: e000922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritchie J. Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. Sage, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lincoln YS. Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tod AM. Interviewing In: Gerrish K, Lacey EA, eds. Research process in nursing. 6th edn Oxford: Backwells, 2010:345–57. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, eds. Analysing qualitative data. London: Routledge, 1994:172–94. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The National Social Marketing Centre. A Starter for Ten: Definitions. http://www.thensmc.com/sites/default/files/Students-1d-definitions_optimised.pdf (accessed Jun 2015).

- 29.National Social Marketing Centre. Big Pocket Guide: Social Marketing. http://www.snh.org.uk/pdfs/sgp/A328463.pdf (accessed Jun 2015).

- 30.Goyat S. The basis of market segmentation: a critical review of literature. Eur J Bus Manag 2011;3:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stead M, Gordon R, Angus K et al. A systematic review of social marketing effectiveness. Health Educ 2007;107:126–91. 10.1108/09654280710731548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warm Well Families. The Warm Well Families Information Sheet. http://www.shu.ac.uk/research/hsc/sites/shu.ac.uk/files/4567_1415RMBC%20BR%20About.pdf (accessed Jun 2015).

- 33.Guertler P, Royston S. For Energy Bill Revolution and Association for the Conservation of Energy Fact file: families and fuel poverty. 2013. http://e3g.org/docs/ACE-and-EBR-fact-file-2013–02-Families-and-fuel-poverty-final.pdf (accessed Jun 2015).

- 34.Frank DA, Neault NB, Skalicky A et al. Heat or eat: the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program and nutritional and health risks among children less than 3 years of age. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1293–302. 10.1542/peds.2005-2943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnardo's (2012) Priced Out: The Plight of Low Income Families and Young People Living in Fuel Poverty London: Barnardo's; http://www.barnardos.org.uk/pricedoutreport.pdf (accessed Jun 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allmark P, Machaczek K. Financial capability, health and disability. BMC Public Health 2015;15:243 10.1186/s12889-015-1589-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]