Abstract

Objective

Type I and II diabetes are associated with a greater relative risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in women than in men. Sex differences in adiposity storage may explain these findings.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 480 813 participants from the UK Biobank without history of CVD was conducted to assess whether the difference in body size in people with and without diabetes was greater in women than in men. Age-adjusted linear regression analyses were used to obtain the mean difference in women minus men in the difference in body size measures, separately for type I and II diabetes.

Results

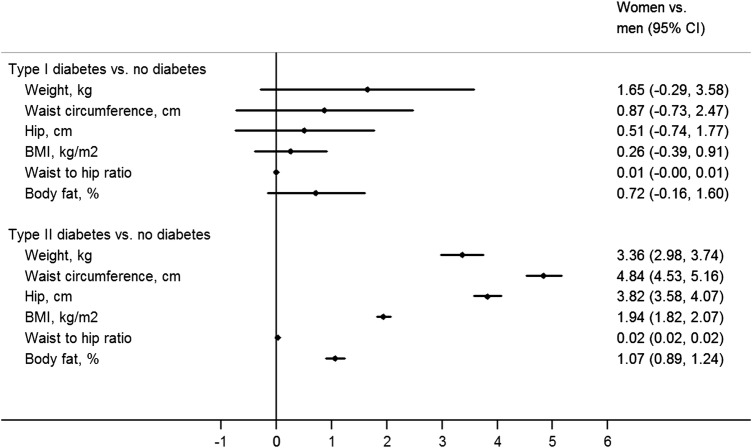

Body size was higher in individuals with diabetes than in individuals without diabetes, particularly in type II diabetes. Differences in body size between individuals with and without type II diabetes were more extreme in women than in men; compared to those without type II diabetes, body mass index and waist circumference were 1.94 (95% CI 1.82 to 2.07) and 4.84 (4.53 to 5.16) higher in women than in men, respectively. In type I diabetes, body size differed to a similar extent between those with and without diabetes in women as in men. This pattern was observed across all prespecified subgroups.

Conclusions

Differences in body size associated with diabetes were significantly greater in women than in men in type II diabetes but not in type I diabetes. Prospective studies can determine whether sex differences in body size associated with diabetes underpin some of the excess risk for CVD in women with type II diabetes.

Keywords: DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The large size and study detail of the UK Biobank enabled us to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of sex differences in the differences in body size associated with diabetes, separately for type I and II diabetes, and across clinically meaningful subgroups.

The identification of individuals with diabetes, and the classification into type I or II diabetes, was based on self-reported data, and misclassification of diabetes status will have occurred. However, any misclassification will have been similar in women and men, and thus, the between-sex comparisons remain valid.

Blood samples, while drawn in all UK Biobank participants, are not yet available for analysis. We were therefore unable to examine sex differences in body size associated with diabetes at different stages of the glucose tolerance spectrum, before the clinical diagnosis of diabetes.

Body size was only measured at study baseline, which for some participants (particularly those with type I diabetes) was already several decades after the diagnosis of diabetes. We were therefore unable to determine whether the greater differences in body size in diabetes in women than in men are the result of diabetes itself, or whether they occurred in the transition from normoglycaemia to the manifestation of overt diabetes.

The cross-sectional nature of the analyses did not enable us to make causal inferences about the role of sex differences in body size on the association between diabetes and chronic disease outcomes. In the future, these can be explored in the UK Biobank once sufficient numbers of events have accrued.

Introduction

Diabetes is a global health problem. An estimated 387 million individuals worldwide have diabetes, and its prevalence is expected to rise to 438 million individuals by 2035.1 2 The vast majority (90%) of individuals with diabetes have type II diabetes while the remaining 10% are individuals with the autoimmune condition of type I diabetes. Aside from population growth and ageing, increasing rates of overweight and obesity worldwide, are considered to be responsible, in large part, for the inexorable rise in the incidence of diabetes.

Diabetes, in either form, greatly increases an individual’s risk of a wide range of conditions, with cardiovascular disease (CVD) being the most common adverse outcome. People with diabetes have about twice the risk of CVD compared with those without diabetes, and it is estimated that CVD accounts for 44% of all fatalities in people with type I diabetes, and for 52% of all fatalities in type II diabetes.3 These estimates, however, assume that diabetes confers the same level of excess risk in women as in men, which is unlikely to be correct. Recent meta-analyses have demonstrated reliably that women with diabetes have a significantly, and clinically important, higher excess risk of both coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke as compared with similarly affected men.4 5 While these meta-analyses predominantly included individuals with type II diabetes, we also observed a greater excess risk of all-cause mortality and vascular events in women with type I diabetes, as compared with men.6

The mechanisms underlying these sex differences in the relationship between diabetes and CVD outcomes are not fully understood. However, accruing evidence suggests that real biological differences between men and women underpin the excess risk of diabetes-related cardiovascular risk in women. A sex differential in patterns of adiposity storage may be of particular importance.7 Previous studies have shown that levels of waist circumference and body mass index (BMI) differed more between women with and without diabetes than between men with and without diabetes.4 8 Moreover, analyses of the UK general practice research database indicated that men develop diabetes at a lower level of BMI compared with women, with levels of BMI being almost 2 units higher in women than in men at the time of diagnosis with type II diabetes.9 The role of body size in type I diabetes is less well established, yet there is increasing evidence that it may play a role in both the development of the condition itself, as in the transition to insulin resistance, the key feature of type II diabetes.10 11

We used data on 480 000 individuals from the UK Biobank without history of CVD to characterise the sex-specific differences in body anthropometry associated with type I and II diabetes. We then examined whether body size differs more between women with and without diabetes than between men with and without diabetes, separately for type I and II diabetes.

Methods

Study population

Baseline data were used from the UK Biobank, a large, prospective, population-based cohort study established to examine the lifestyle, environmental and genetic determinants of a range of diseases of adulthood.12 Between 2006 and 2010, 502 712 men and women aged 40–69 years at baseline attended 1 of the 22 centres across the UK for detailed baseline assessment that involved collection of extensive questionnaire data, physical measurements and biological samples. In order to determine whether a sex difference in body composition associated with diabetes could explain the findings from previous meta-analyses,4 5 analyses were restricted to individuals without a self-reported medical history of stroke or CHD. Participants with missing data on history of diabetes were excluded.

Definitions and measurements

The presence of diabetes was based on a self-reported medical diagnosis. Age at first diagnosis of diabetes, and the use of medications for cholesterol, blood pressure or diabetes regulation were self-reported at study baseline. Type I diabetes was defined as the presence of the combination of a self-reported medical diagnosis of diabetes, an age at first diagnosis before 30 years, and the use of an insulin product. All other participants with a self-reported medical diagnosis of diabetes were considered to have type II diabetes. Smoking status was self-reported. Socioeconomic status was measured using the Townsend Deprivation Score, an area of residence-based index of material deprivation. Baseline physical measurements were obtained by trained staff using standardised procedures and regularly calibrated equipment. Blood pressure was measured using the Omron HEM-7015IT digital blood pressure monitor. Standing height was measured using a Seca 202 height measure. Waist and hip circumference were measured using a Wessex non-stretchable sprung tape measure. Weight and body fat percentage were measured using the Tanita BC-418 MA body composition analyser. BMI was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by the square of the standing height (m2). Waist-to-hip ratio was derived by dividing the waist circumference by the hip circumference.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics are presented as means (SD) for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables, separately by sex and diabetes status. Linear regression analyses were used to estimate the diabetes minus no diabetes differences in mean levels of cardiovascular risk factors, separately by sex and diabetes subtype. Linear regression analyses were also used to estimate the women minus men differences in the differences in mean risk factor levels conferred by type I or II diabetes. All models were adjusted for age. Secondary analyses were stratified by age at study baseline, socioeconomic status, ethnic background, time since diagnosis of diabetes and age at diagnosis of diabetes. In the sensitivity analyses, we also included individuals with pre-existing CVD, and defined type I diabetes as (1) an age at diagnosis <35 years and the exclusive report of insulin (and no other diabetes treatment) and (2) an age at diagnosis <35 years and having started insulin within 1 year of diagnosis of diabetes. R V.2.15.3 was used for all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the 480 813 study participants are shown in table 1. Of these, 55% were women, 827 (45% women) had type I diabetes and 22 626 (42% women) had type II diabetes. Mean age at study baseline was 56 (SD 8) years, with individuals with type I diabetes being slightly younger, and individuals with type II diabetes being slightly older than their counterparts without diabetes. Individuals with type I diabetes were, on average, diagnosed with the condition when 18 years of age (SD 7), and individuals with type II diabetes had a mean age of 52 (SD 11) years at time of diagnosis (see eFigure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants by sex and diabetes type

| Women |

Men |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No diabetes | Type I | Type II | No diabetes | Type I | Type II | |

| N | 480 813 | 256 757 (96.3) | 369 (0.1) | 9396 (3.5) | 200 603 (93.6) | 458 (0.2) | 13 230 (6.2) |

| Age (years) | 480 813 | 56.2 (8.0) | 53.7 (7.8) | 58.8 (7.4) | 56.2 (8.2) | 55.4 (8.1) | 59.8 (7.0) |

| Ethnic background | 479 369 | ||||||

| White | 94.8 | 93.8 | 84.9 | 94.7 | 93.9 | 87.5 | |

| Mixed or non-white | 5.0 | 5.7 | 14.7 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 12.0 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 448 985 | 135.0 (19.3) | 137.3 (17.5) | 139.5 (17.9) | 140.9 (17.4) | 141.0 (16.0) | 142.6 (16.9) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 448 990 | 80.7 (10.0) | 74.6 (9.0) | 80.9 (9.8) | 84.4 (10.0) | 77.3 (9.6) | 82.5 (9.5) |

| Height (m) | 475 486 | 162.6 (6.3) | 163.1 (6.5) | 160.9 (6.5) | 175.9 (6.8) | 175.1 (7.3) | 174.4 (6.8) |

| Weight (kg) | 475 288 | 70.9 (13.7) | 73.9 (15.2) | 83.2 (18.3) | 85.3 (13.8) | 86.4 (16.5) | 94.1 (17.8) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 475 805 | 84.1 (12.1) | 86.8 (14.3) | 98.1 (14.9) | 96.1 (10.8) | 98.2 (13.8) | 105.5 (13.4) |

| Hip (cm) | 475 755 | 103.0 (10.1) | 104.8 (10.9) | 111.0 (13.9) | 103.1 (7.3) | 104.4 (9.3) | 107.3 (10.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 475 002 | 26.9 (5.0) | 27.7 (5.2) | 32.1 (6.7) | 27.5 (4.0) | 28.2 (4.7) | 30.9 (5.3) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 475 712 | 0.81 (0.07) | 0.83 (0.09) | 0.88 (0.08) | 0.93 (0.06) | 0.94 (0.08) | 0.98 (0.07) |

| Body fat (%) | 468 631 | 36.4 (6.8) | 36.1 (7.1) | 41.4 (6.7) | 24.9 (5.7) | 24.1 (6.9) | 28.9 (5.9) |

| Smoking status (%) | 480 809 | ||||||

| Never | 59.7 | 59.1 | 58.5 | 50.5 | 52.6 | 40.0 | |

| Previous | 31.2 | 33.3 | 32.2 | 36.8 | 36.5 | 47.3 | |

| Current | 8.8 | 7.3 | 8.7 | 12.3 | 10.3 | 12.0 | |

| Socioeconomic status | 480 211 | ||||||

| Lower | 18.4 | 23.0 | 29.8 | 19.0 | 27.3 | 28.2 | |

| Middle | 29.9 | 33.6 | 30.9 | 29.1 | 27.3 | 29.3 | |

| Higher | 51.5 | 43.4 | 39.1 | 51.7 | 45.4 | 42.4 | |

| Antidiabetic medications (%) | 480 813 | ||||||

| Insulin product | 100.0 | 14.0 | 100.0 | 13.3 | |||

| Any oral antidiabetic drugs | 16.8 | 53.3 | 19.2 | 58.1 | |||

| Lipid-lowering medication (%) | 480 813 | 7.7 | 65.9 | 61.8 | 12.6 | 75.1 | 68.9 |

| Antihypertensive medications (%) | 480 813 | 11.6 | 55.0 | 52.7 | 14.7 | 66.8 | 59.0 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 18 381 | 17.8 (7.4) | 52.6 (10.5) | 18.4 (7.2) | 51.9 (11.3) | ||

Type I diabetes was defined as an age at diagnosis <30 years, and using insulin. All other participants with a self-reported history of diabetes were classified as type II diabetes.

BMI, body mass index.

Medication use

In individuals without diabetes, 8% of women and 13% of men used some form of lipid-level modifying therapy, mostly statins, and 12% of women and 15% of men were on blood pressure-lowering medications. In individuals with type I diabetes, 66% of women and 75% of men were on lipid-level modifying therapies, and 55% of women and 67% of men used blood pressure-lowering therapies. In type II diabetes, 62% of women and 69% of men were on lipid level-lowering therapy, and 53% of women and 59% of men used blood pressure-lowering medications. In individuals with type I diabetes, 17% of women and 19% of men used oral glucose-lowering therapies in addition to insulin. In type II diabetes, 59% of women and 63% of men were on some form of glucose level lowering medications, mostly metformin.

Differences in body size in men and women with type I diabetes

Body size was generally slightly less favourable in individuals with type I diabetes than in individuals without diabetes (table 2). For example, waist circumference was 3 cm greater in women with type I diabetes, and 2 cm greater in men with type I diabetes as compared to their non-affected counterparts. BMI was also somewhat higher in women and men with type I diabetes. The women-to-men differences in the sex-specific differences indicated that differences in levels of body size in women were similar to those observed in men (figure 1). Differences between women and men in waist circumference and BMI were generally similar across a range of subgroup analyses (table 3). Defining type I diabetes as those individuals aged <35 years at diagnosis who reported using insulin but no other diabetes treatment, or as an age at diagnosis <35 years and having started insulin within 1 year of diagnosis of diabetes, did not alter the findings materially (see eTables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Age-adjusted differences (95% CIs) in baseline characteristics between individuals with and without diabetes, by sex and diabetes type

| Women |

Men |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔType I diabetes | ΔType II diabetes | ΔType I diabetes | ΔType II diabetes | |

| Weight (kg) | 2.84 (1.41 to 4.27) | 12.40 (12.11 to 12.69) | 1.05 (−0.25 to 2.35) | 9.33 (9.08 to 9.58) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 3.11 (1.86 to 4.36) | 13.63 (13.38 to 13.88) | 2.17 (1.16 to 3.18) | 8.92 (8.73 to 9.12) |

| Hip (cm) | 1.84 (0.79 to 2.89) | 7.92 (7.71 to 8.14) | 1.25 (0.57 to 1.94) | 4.24 (4.11 to 4.38) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.93 (0.41 to 1.45) | 5.17 (5.07 to 5.28) | 0.62 (0.24 to 1.00) | 3.34 (3.26 to 3.41) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.014 (0.007 to 0.021) | 0.065 (0.064 to 0.067) | 0.009 (0.003 to 0.014) | 0.046 (0.045 to 0.047) |

| Body fat (%) | 0.04 (−0.66 to 0.74) | 4.68 (4.54 to 4.82) | −0.70 (−1.23 to −0.17) | 3.65 (3.55 to 3.75) |

Type I diabetes was defined as an age at diagnosis <30 years, and using insulin. All other participants with a self-reported history of diabetes were classified as type II diabetes.

BMI, body mass index.

Figure 1.

Women minus men difference in age-adjusted differences (95% CIs) in body size measures associated with type I and II diabetes. Type I diabetes was defined as an age at diagnosis <30 years, and using insulin. All other participants with a self-reported history of diabetes were classified as type II diabetes (BMJ, body mass index).

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses of women minus men difference in age-adjusted differences (95% CIs) in waist circumference and BMI associated with type I diabetes

| Type I diabetes |

||

|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline (years) | <55 | ≥55 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 2.56 (0.24 to 4.88) | 1.10 (−1.14 to 3.34) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.91 (−0.05 to 1.87) | 0.40 (−0.48 to 1.29) |

| Socioeconomic status | Higher SES | Lower SES |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.47 (−1.81 to 2.75) | 0.95 (−1.31 to 3.20) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.35 (−0.55 to 1.25) | 0.11 (−0.82 to 1.04) |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | <30 | ≥30 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 1.74 (−1.39 to 4.87) | 0.60 (−1.24 to 2.44) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.78 (−0.47 to 2.04) | 0.09 (−0.65 to 0.83) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | <18 | ≥18 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.98 (−1.38 to 3.33) | 0.84 (−1.30 to 2.99) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.21 (0.73 to 1.16) | 0.31 (−0.55 to 1.18) |

| Ethnic background | White | Mixed or non-white |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.92 (−0.73 to 2.58) | 0.77 (−6.02 to 7.55) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.27 (−0.39 to 0.94) | 0.89 (−2.01 to 3.79) |

Type I diabetes was defined as an age at diagnosis <30 years, and using insulin.

BMI, body mass index.

Differences in body size in men and women with type II diabetes

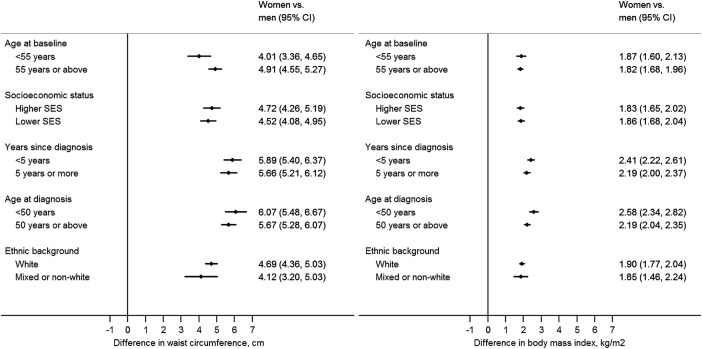

Irrespective of the measure, body size was significantly larger in individuals with type II diabetes than in those without diabetes (table 2). Women with type II diabetes had a waist circumference that was about 14 cm greater, and a BMI that was 5 kg/m2 higher than women without diabetes. Waist circumference was 9 cm greater, and BMI was 3 kg/m2 higher in men with type II diabetes as compared with men without diabetes. Consequently, sex differences (women minus men) in measures of body size between those with and without diabetes were greater in women than in men: for BMI, the sex difference was 2 kg/m2 and 5 cm for waist circumference. These sex differences were consistently observed across subgroup analyses based on age at study baseline, socioeconomic status, time since diagnosis of diabetes, and age at diagnosis (figure 2). Results were virtually identical in the sensitivity analyses among all individuals, including those with pre-existing CVD (see eTable 3).

Figure 2.

Subgroup analyses of women minus men difference in age-adjusted differences (95% CIs) in waist circumference and BMI associated with type II diabetes. Type I diabetes was defined as an age at diagnosis <30 years, and using insulin. All other participants with a self-reported history of diabetes were classified as type II diabetes (SES, socioeconomic status).

Discussion

Multiple studies have shown that the excess risk of CVD associated with both type I and II diabetes is considerably greater in women than in men.4–6 Several explanations have been propounded to explain the excess vascular hazard conferred by diabetes in women compared with men including sex differences in behaviour, treatment and physiology, but the evidence for any of these remains largely speculative.13 Given the strong causative role that body size has on risk of diabetes (in particular, type II diabetes) and subsequent vascular disease, we explored whether sex differences in measures of body size in individuals with and without diabetes exist using data from the large contemporary middle-aged population of the UK Biobank. Overall, we observed body size to be substantially greater in individuals with diabetes than in those without diabetes, especially for type II diabetes. Moreover, the difference in mean body size between those with and without type II diabetes was significantly larger in women than in men (but not for type I diabetes) suggesting that greater body size may underpin some of the excess vascular risk in women with type II diabetes relative to men.

Sex differences in measures of body size among individuals with type II diabetes are in line with previous reports of a greater metabolic deterioration in the transition to diabetes in women than in men.8 9 14–17 We have previously hypothesised that it may not be sex differences in the effects of diabetes itself, but rather the more detrimental metabolic changes for women before the onset and treatment of overt diabetes that explains the excess risk of CVD associated with diabetes.13 This hypothesis is supported by data from the British Regional Heart Study, and the British Women's Health and Heart Study, which showed that women with diabetes had greater relative differences in many cardiovascular risk factors than men with diabetes, which were potentially mediated by greater differences in central adiposity and insulin resistance in women.8 Moreover, the UK Prospective Diabetes Study demonstrated that women with newly diagnosed type II diabetes were considerably more obese than their male counterparts, being 141% vs 120% of ideal body weight, respectively.18 Similar results were found in diabetes registries in England and Scotland; mean level of BMI was nearly 2 kg/m2 higher in women than men when first diagnosed with diabetes.9 16 Both studies demonstrated that the difference in BMI at the time of diagnosis of diabetes was most marked at younger ages and narrowed with advancing age. The Scottish data showed that the difference in BMI at diagnosis with diabetes was unrelated to the levels of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels within 1 year of diagnoses.16 These data indicate that men and women were diagnosed at a similar stage of disease, despite the higher consultation rates in women in the general population.19 The greater difference in body size associated with diabetes type II in women as compared to men might be explained by differences between men and women in adiposity storage capacities. Women generally have more subcutaneous fat storage capacities than men, and therefore need to gain more weight before the less hazardous subcutaneous storage becomes exhausted and excess adipose tissue is placed into the more visceral and ectopic tissues linked to insulin resistance and diabetes. Hence, this sex difference in the preferential location of fat storage, and the associated greater metabolic deterioration in women than in men, may explain some of the greater excess risk for CVD observed in women with type II diabetes, compared with their male counterparts.

Although overweight and obesity are widely understood to be linked to insulin resistance and type II diabetes, its contribution to the onset and progression of type I diabetes is not fully understood. However, the rise in incident type I diabetes runs contemporaneous with the obesity epidemic, implying a possible aetiological role of obesity in type I diabetes.20 21 A recent nationwide cohort study among 1.2 million Swedish children born between 1992 and 2004 examined the association between maternal body size and the risk of type I diabetes in offspring.22 Children of parents without diabetes had a significant 10% and 33% increased risk of type I diabetes when the mother was overweight or obese (compared with having a mother of normal weight), respectively. No increases in risk were found among children of parents with diabetes. A large-scale analysis pooling data from 29 studies including 12 807 cases of type I diabetes showed that every 500 g additional birth weight was associated with a 4% increased risk of type I diabetes,23 independent of possible confounding factors such as gestational age, maternal age, breastfeeding, Caesarean section delivery and maternal diabetes. Likewise, a meta-analysis of nine studies comprising a total of 2700 cases of type I diabetes showed that childhood obesity,24 and a 1 SD higher BMI increased the risk of type I diabetes, with pooled ORs of 2.03 and 1.25 for childhood obesity and childhood BMI, respectively. While these findings support the role of obesity in the occurrence of type I diabetes, none of these studies specifically examined whether the impact of obesity in the development and progression of type I diabetes, and its effects on vascular-related disease, is equivalent between the sexes.

In conclusion, differences in body size associated with diabetes were significantly greater in women than in men in type II diabetes but not in type I diabetes. A greater difference in body anthropometry associated with diabetes in women compared with men might be responsible for the greater excess risk for CVD in women with type II diabetes as compared to men. Sex differences in the effect of type I diabetes and vascular events, however, are likely to be driven by mechanisms other than body anthropometry. These hypotheses can be explored in the UK Biobank once sufficient numbers of events have accrued. In either case, adequate weight control remains crucial for the prevention or delay of diabetes, and for the onset of its major vascular complications.

Footnotes

Contributors: SP contributed to the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. RRH and MW made important revisions to the draft manuscript. All authors conceived the study, participated in data interpretation, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: UK Biobank has obtained Research Tissue Bank approval from its governing Research Ethics Committee, as recommended by the National Research Ethics Service. No separate ethics approval was required. Permission to use the UK Biobank Resource was approved by the Access Sub-Committee of the UK Biobank Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 6th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2.7 million participants. Lancet 2011;378:31–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrish NJ, Wang SL, Stevens LK et al. Mortality and causes of death in the WHO multinational study of vascular disease in diabetes. Diabetologia 2001;44(Suppl 2):S14–21. 10.1007/PL00002934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as a risk factor for stroke in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts, including 775,385 individuals and 12,539 strokes. Lancet 2014;383:1973–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60040-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts including 858,507 individuals and 28,203 coronary events. Diabetologia 2014;57:1542–51. 10.1007/s00125-014-3260-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huxley RR, Peters SA, Mishra GD et al. Risk of all-cause mortality and vascular events in women versus men with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:198–206. 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70248-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sattar N. Gender aspects in type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiometabolic risk. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;27:501–7. 10.1016/j.beem.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wannamethee SG, Papacosta O, Lawlor DA et al. Do women exhibit greater differences in established and novel risk factors between diabetes and non-diabetes than men? The British Regional Heart Study and British Women's Heart Health Study . Diabetologia 2012;55:80–7. 10.1007/s00125-011-2284-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul S, Thomas G, Majeed A et al. Women develop type 2 diabetes at a higher body mass index than men. Diabetologia 2012;55:1556–7. 10.1007/s00125-012-2496-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Islam ST, Srinivasan S, Craig ME. Environmental determinants of type 1 diabetes: a role for overweight and insulin resistance. J Paediatr Child Health 2014;50:874–9. 10.1111/jpc.12616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Versini M, Jeandel PY, Rosenthal E et al. Obesity in autoimmune diseases: not a passive bystander. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:981–1000. 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001779 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters SA, Huxley RR, Sattar N et al. Sex differences in the excess risk of cardiovascular diseases associated with type 2 diabetes: potential explanations and clinical implications. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2015;9:36 10.1007/s12170-015-0462-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donahue RP, Rejman K, Rafalson LB et al. Sex differences in endothelial function markers before conversion to pre-diabetes: does the clock start ticking earlier among women? The Western New York Study. Diabetes Care 2007;30:354–9. 10.2337/dc06-1772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haffner SM, Miettinen H, Stern MP. Relatively more atherogenic coronary heart disease risk factors in prediabetic women than in prediabetic men. Diabetologia 1997;40:711–17. 10.1007/s001250050738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logue J, Walker JJ, Colhoun HM et al. Do men develop type 2 diabetes at lower body mass indices than women? Diabetologia 2011;54:3003–6. 10.1007/s00125-011-2313-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansfield MW, Heywood DM, Grant PJ. Sex differences in coagulation and fibrinolysis in white subjects with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996;16:160–4. 10.1161/01.ATV.16.1.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.[No authors listed]. UK Prospective Diabetes Study. IV. Characteristics of newly presenting type 2 diabetic patients: male preponderance and obesity at different ages. Multi-center study. Diabet Med 1988;5:154–9. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1988.tb00963.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Hunt K, Nazareth I et al. Do men consult less than women? An analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003320 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS, Michels AW. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2014;383:69–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60591-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyürüs E et al. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet 2009;373:2027–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hussen HI, Persson M, Moradi T. Maternal overweight and obesity are associated with increased risk of type 1 diabetes in offspring of parents without diabetes regardless of ethnicity. Diabetologia 2015;58:1464–73. 10.1007/s00125-015-3580-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardwell CR, Stene LC, Joner G et al. Birthweight and the risk of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis of observational studies using individual patient data. Diabetologia 2010;53:641–51. 10.1007/s00125-009-1648-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verbeeten KC, Elks CE, Daneman D et al. Association between childhood obesity and subsequent type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2011;28:10–18. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]