Abstract

Introduction

Catheter-related infection (CRI) is a difficult clinical problem in renal medicine, with blood stream infections occurring in up to 40% of patients with haemodialysis (HD) catheters, conferring significant rates of morbidity and mortality. Several approaches have been assessed as a means to prevent CRI. Currently, an intervention that is the source of much discussion is the use of antimicrobial lock solutions (ALS). A number of past conventional meta-analyses have compared different ALS with heparin. However, there is no consensus recommendation regarding which type of ALS is best. The purpose of our study is to carry out a network meta-analysis comparing the efficacy of different ALS for prevention of CRI in patients with HD and ranking these ALS for practical consideration.

Methods and analysis

We will search six electronic databases, earlier relevant meta-analyses and reference lists of included studies for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared ALS for preventing episodes of CRI in patients with HD either head-to-head or against control interventions using non-ALS. Study selection and data collection will be performed by two reviewers independently. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool will be used to assess the quality of included studies. The primary outcome of efficacy will be catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI). We will perform a Bayesian network meta-analysis to compare the relative efficacy of different ALS by WinBUGS (V.1.4.3) and STATA (V.13.0). The quality of evidence will be assessed by GRADE.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required given that this study includes no confidential personal data and no data on interventions on patients. The results of this study will be submitted to a peer-review journal for publication.

Trial registration number

CRD42015027010.

Keywords: antimicrobial lock solution, haemodialysis, catheter-related infection, central venous catheters, network meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first comprehensive review comparing the efficacy of different antimicrobial lock solutions through network meta-analysis.

This Bayesian network meta-analysis can integrate direct evidence with indirect evidence from multiple treatment comparisons to estimate the interrelations across all treatments.

We will use the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to evaluate the quality of evidence.

This study will provide evidence for clinical decision makers to formulate better prevention of catheter-related infection.

This study is inherently retrospective and based on published randomised controlled trials only.

Introduction

Central venous catheters (CVCs) remain a common form of vascular access for patients with chronic haemodialysis (HD) despite recommendations by several national and international guidelines to minimise their usage as much as possible.1 2 It has been estimated that almost 30–40% of patients with chronic HD are dependent on CVCs for their vascular access.1–3 Widespread application of CVCs exposes patients to an enhanced risk for catheter-related infection (CRI), which includes catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) and exit-site infection. The incidence of CRI varies per dialysis unit, site of insertion, type of catheter inserted and adequacy of catheter care. Generally, the incidence of episodes of CRBSI ranges between 2.5 and 5.5 cases/1000 catheter days for tunnelled catheters, and between 3.8 and 12.8 cases/1000 catheter days for non-tunnelled catheters.4 5 Episodes of exit site infection vary from 0.35 to 8.3 cases/1000 catheter days and 8.2 to 16.75 cases/1000 catheter days for tunnelled and non-tunnelled catheters, respectively.6–8

CRI is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. According to the US Renal Data System, infection is the second leading cause of death in patients with end-stage renal disease,9 and the leading cause of catheter removal and morbidity in dialysis patients.10 11 Data from non-tunnelled catheters used in intensive care units indicate an average 3% per annum mortality rate.12 Besides, the costs to the healthcare system are also substantial. It has been estimated that the cost per infection is an estimated $34 508–$56 000,13 14 and the annual cost of caring for patients with CVC-associated BSIs ranges from $296 million to $2.3 billion. Therefore, it is a clinical challenge to prevent CRI.

CRI results from migration of skin organisms along the catheter into the bloodstream or contamination and colonisation of catheter lumens. Prevention strategies are directed at decreasing growth and/or adherence of pathogens to the catheter hub and surface. Currently, several modalities including intraluminal and extraluminal approaches have been assessed as a means to prevent CRI, which suggested confusion regarding best practice in this area. A recent promising technique has been used to instil an antimicrobial solution into the lumen(s) of the catheter between HD sessions in order to address intraluminal sources of infection. It is known from in vitro studies that solutions containing antimicrobials can prevent biofilm formation.15 Biofilm constitutes a permanent source of bacteraemia as well as being a key factor favouring bacterial resistance.16 At the same time, there have been concerns about the real efficacy and toxicity of antimicrobial lock solution (ALS) in case of overfills, especially at high concentrations.

Over recent years, the growing number of clinical research projects investigating this approach attests to the benefits of ALS in preventing CRI. Efforts to evaluate and compare the efficacy of ALS for the prevention of CRI have also been performed in almost 10 meta-analyses that used conventional methodologies. Jaffer et al17 meta-analysed seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with HD, revealing that antibiotic lock solutions reduced the frequency of CRI without producing significant side effects. Another meta-analysis of the use of ALS for patients with HD concluded that antibiotic lock solutions reduced CRBSI.18 Similarly, six other meta-analyses confirmed the positive impact of ALS in reducing CRI.19–23 These available antibiotic lock solutions include gentamicin, vancomycin, cefotaxime and cefazolin. In addition, Liu et al's24 meta-analysis results found that taurolidine-citrate catheter lock solutions reduced the risk of CRI, and another meta-analysis showed that participants using ethanol locks had a lower CRBSI-rate per 1000 catheter days in comparison to those using heparin locks.25 In a word, results from this relevant literature indicated that ALS had a positive effect on the reduction of CRI.

However, because different head-to-head ALS trials are scarce, these systematic reviews and meta-analyses have not focused on any head-to-head comparisons of different ALS. Besides, the main drawback of the current state of the art is that meta-analysis focuses on comparing only two alternatives, while decision-makers need to know the relative ranking of a set of alternative options and not only whether option A is better than B. That is, there is no consensus recommendation regarding which ALS is best.

Thus, the evidence for the efficacy of these ALS in prevention of CRI has never been assessed in the comprehensive setting of a systematic review and meta-analysis. For these reasons, a better-designed approach utilising Bayesian network meta-analysis is urgently needed in this area, integrating direct evidence (from studies directly comparing interventions) with indirect evidence (information about two interventions derived via a common comparator) from multiple intervention comparisons, to estimate the interrelations across all interventions.26 27

The purpose of our study is to carry out a network meta-analysis comparing the efficacy of different ALS for prevention of CRI for patients with HD, based on existing RCT, and ranking these ALS for practical consideration. This study is expected to begin in September 2015 and conclude in February 2016.

Objective

The objective of this study is to explore the efficacy of ALS to prevent CRI for patients undergoing HD, using a network meta-analysis.

Methods

Design

Bayesian network meta-analysis will be used in this study. This protocol of network meta-analysis will be conducted and reported mainly according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P),28 and the PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analysis.29

Inclusion criteria

Type of study

All relevant RCTs will be included. Quasi-randomised trials will be excluded.

Participants

The participants must be adults, aged at least 18 years, who had started or were about to start either short-term or maintenance HD using tunnelled or non-tunnelled CVC as vascular access, regardless of the type of kidney failure (acute or chronic), whatever the cause and duration of use of the catheter.

Type of interventions

RCTs of ALS used to prevent CRI in patients with HD will be included, regardless of whether the antimicrobials were tested between themselves (head-to-head) or against placebo/control intervention such as heparin. For antimicrobials, antibiotic, citrate, taurolidine and alcohol will be included regardless of their concentration. All ALS could be given with anticoagulants (eg, heparin, citrate or EDTA).

Outcomes of interest

The primary outcome will be CRBSI. The Centers for Disease Control definitions for CRBSI will be used.30 Only RCTs that used this definition, or RCTs where the results were detailed enough to be re-adjudicated according to the aforementioned definition, will be included. In cases where a study separately reported definite, probable and possible CRBSI, we will choose not to include ‘possible’ blood stream infection (defined as the absence of laboratory confirmation of blood stream infection).

The secondary outcomes will be exit site infection (defined as the development of a purulent exudate or redness around the site not resulting from residual stitches), all-cause mortality and adverse events as reported by the study author.

Other criteria

Other inclusion criteria: The RCTs must report sufficient data for calculating the risks of CRBSI in the intervention and control group. Other exclusion criteria are (1) duplicate or redundant studies, (2) combined interventions with multiple antimicrobial solutions and (3) studies dealing with the treatment of CRI rather than with prophylaxis.

Data sources and search

We will systematically perform an electronic search of PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE (via Embase.com platform), Sciences Citation Index (via Web of Knowledge platform), CINAHL (via EBSCO platform) and Chinese Biomedical Literature Database from their inception to September 2015, with no language restrictions. In addition, we will search unpublished theses and dissertations via Conference Proceedings Citation Index, China Proceeding of Conference Full-text Database, China Doctoral Dissertation Full-text Database, China Master's Theses Full-text Database and the System for Information on Gray Literature database in Europe (SIGLE). We will also search the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (http://www.who.int/trialsearch/) for ongoing trial registers. Relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses from these databases will be identified and bibliographies will be scrutinised for further relevant trials, as well as those of RCTs included in the review. The search strategy will be developed by Zhang Jun and Tian JinHui (with more than 10 years of experience as an information specialists). The search method will include relevant text and medical subject headings related to HD, infection, CVC and RCT. The exact search strategy used in the PubMed database is provided as an example in online supplementary file S1.

Selection of literature

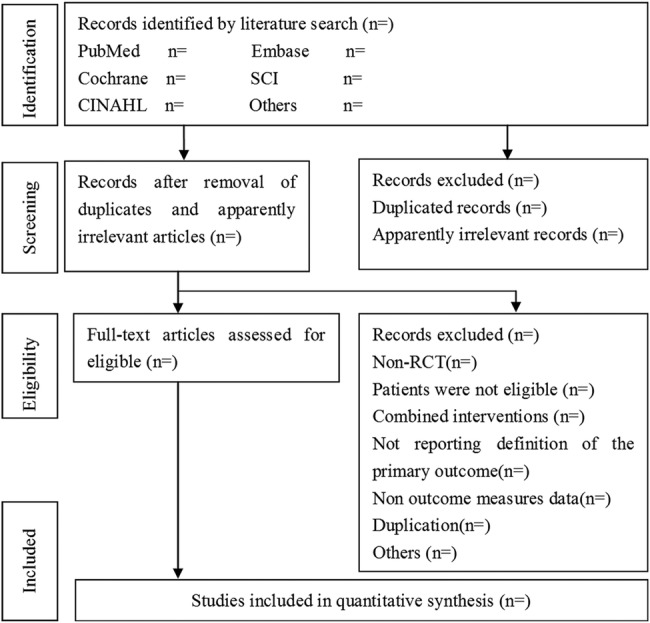

Literature search results will be imported into EndNote X6 literature management software. Two authors (R-KL and K-XC) will independently review the literature searches from the title, abstract or descriptors and will exclude studies that clearly do not meet the inclusion criteria. After excluding the duplicated and apparently irrelevant studies, the remaining studies will be reviewed in full text to assess eligibility for inclusion. Any disagreements will be resolved by discussion or by seeking an independent third opinion (J-HT). Excluded trials and the reason for their exclusion will be listed and examined by a third reviewer (J-HT). Selection process of relevant studies retrieved from databases will be shown in a PRISMA-compliant flow chart (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection (RCT, randomised controlled trial).

Data extraction

Two authors (JZ and LG) will independently extract the data from each study, using a standardised data extraction checklist, which will include study characteristics (eg, first author's name, publication year, journal, country where the study was conducted), characteristics of study subjects (eg, number of participants, age, gender distribution), characteristics of catheter (eg, type of catheters, number of catheters), intervention details (eg, type and concentration of lock solutions, patient involvement, duration of HD, number of catheter days), outcome variables (eg, number of episodes) and any additional prophylactic measures used that may have affected outcomes (eg, catheter care). Outcomes will be extracted preferentially by intention to treat (ITT) at the end of interventions. Quantitative data will be extracted to calculate effect sizes. Data on effect size that could not be obtained directly will be recalculated, when possible. Any discrepancy will be resolved by consensus. If necessary, we will try to contact the corresponding authors for more information.

Methodological quality assessment

Two authors (JZ and LG) will independently evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies for major potential sources of bias by using the Cochrane Collaboration's risk of bias tool,31 which includes method of random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (detection bias), selective reporting (detection bias) and other sources of bias. We will evaluate the methodological quality of each study on each criterion as low, high or unclear risk of bias. Any disagreements will be resolved through discussion, if need be, with another reviewer (J-HT).

Statistical analysis

We will perform a Bayesian network meta-analysis to assess the relative outcomes of different ALS and control conditions with each other from all direct and indirect comparisons. Dichotomous outcomes will be analysed on an ITT basis.

Network meta-analysis

Bayesian network meta-analysis will be performed using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method in WinBUGS 1.4.3 (http://www.mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk/bugs/winbugs/contents.shtml). The other analyses will be performed and presented through STATA V.13.0 using the mvmeta command. The results of dichotomous outcomes will be reported as posterior medians of odds ratio (OR) with 95% credible intervals (CrIs). The fixed and random effects models with vague priors for multi-arm trials will be used. The choices between fixed and random-effects models will be made by comparing the deviance information criteria (DIC) for each model. The model with the lowest DIC will be preferred (differences >3 are considered meaningful).32 Three Markov chains will be run simultaneously with different arbitrarily chosen initial values. To ensure convergence, trace plots and Brooks-Gelman-Rubin plots will be assessed.33 Convergence will be found to be adequate after running 20 000 samples for three chains. These samples will then be discarded as ‘burn-in’, and posterior summaries will be based on 100 000 subsequent simulations. When a loop connects three treatments, it will be possible to evaluate the inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence. The node splitting method will be used to calculate the inconsistency of the model; this separates evidence on a particular comparison into direct and indirect evidence.34

We will estimate the ranking probabilities, for all treatments, of being at each possible rank for each intervention. Then, we will obtain the treatment hierarchy using the probability of being the best treatment, by using the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA). The larger the SUCRA value, the better the rank of the treatment with a SUCRA of 1.0 if an intervention always ranks first and 0.0 if it always ranks last.35

Investigation and treatment of heterogeneity

We will assess clinical and methodological heterogeneity by carefully examining the characteristics and design of included trials. Statistical heterogeneity among the studies and in the entire network will be assessed on the bias of the magnitude of heterogeneity variance parameter (I2 or τ2) estimated from network meta-analysis models using R V.3.2.2 software (https://cran.r-project.org/src/base/R-3/). Network meta-regression or subgroup analysis will be used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity. Network meta-regression will be conducted using random effects network meta-regression models to examine potential effect moderators such as age of participants, site of catheter insertion, type of catheter, duration of HD, sample size and study quality. Where possible, we will perform the subgroup analysis according to the concentration of ALS.

If we include enough trials per comparison, a sensitivity analysis will be conducted. We will conduct a sensitivity analysis by excluding trials where the criterion of CRBSI diagnosis does not meet the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines. We will also conduct another sensitivity analysis excluding trials with a total sample size of <50 randomised patients.

Funnel plot analysis

Publication bias will be examined with the Begg’s36 and Egge’s37 funnel plot method. A contour-enhanced funnel plot will be used as an aid to distinguish asymmetry due to publication bias from that due to other factors.

Quality of evidence

The quality of evidence will be assessed by the GRADE four-step approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis38: (1) Present direct and indirect treatment estimates for each comparison of the evidence network. (2) Rate the quality of each direct and indirect effect estimate. (3) Present the network meta-analysis estimate for each comparison of the evidence network. (4) Rate the quality of each network meta-analysis effect estimate. The quality of evidence will be classified by the GRADE group into four levels: high quality, moderate quality, low quality and very low quality. The quality rating of RCT may be rated down by −1 (serious concern) or −2 (very serious concern) for the following reasons: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias. This process will be performed using GRADE pro 3.6 software (http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical issues

As no primary data collection will be undertaken, no additional formal ethical assessment and no informed consent are required.

Publication plan

This network meta-analysis will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal. It will be disseminated electronically and in print.

Footnotes

Contributors: JZ and J-HT participated in the conception and design of the study, including search strategy development. JZ and K-XC tested the feasibility of the study. All the authors drafted and critically reviewed this manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Rayner HC, Besarab A, Brown WW et al. Vascular access results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): performance against Kidney Diseases Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) Clinical Practice Guidelines. Am J Kidney Dis 2004;44:22–6. 10.1016/S0272-6386(04)01101-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendelssohn DC, Ethier J, Elder SJ et al. Haemodialysis vascular access problems in Canada: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS II). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21:721–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfi281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisoni RL, Young EW, Dykstra DM et al. Vascular access use in Europe and the United States: results from the DOPPS. Kidney Int 2002;61:305–16. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00117.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kairaitis LK, Gottlieb T. Outcome and complications of temporary haemodialysis catheters. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999;14:1710–14. 10.1093/ndt/14.7.1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver MJ, Callery SM, Thorpe KE et al. Risk of bacteremia from temporary hemodialysis catheters by site of insertion and duration of use: a prospective study. Kidney Int 2000;58:2543–5. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00439.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Develter W, De Cubber A, Van Biesen W et al. Survival and complications of indwelling venous catheters for permanent use in hemodialysis patients. Artif Organs 2005;29:399–405. 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2005.29067.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson KB, Adcox MJ, Mallea MC et al. Standardized surveillance of hemodialysis vascular access infections: 18-month experience at an outpatient, multifacility hemodialysis center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2000;21:200–3. 10.1086/501744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weijmere MC, Vervloet MG, ter Wee PM. Compared to tunnelled cuffed haemodialysis catheters, temporary untunnelled catheters are associated with more complications already within 2 weeks of use. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:670–7. 10.1093/ndt/gfg581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabindranath KS, Bansal T, Adams J et al. Systematic review of antimicrobials for the prevention of haemodialysis catheter-related infections. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:3763–74. 10.1093/ndt/gfp327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marr KA, Sexton DJ, Conlon PJ et al. Catheter-related bacteremia and outcome of attempted catheter salvage in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:275–80. 10.7326/0003-4819-127-4-199708150-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butterly DW, Schwab SJ. Dialysis access infections. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2000;9:631–5. 10.1097/00041552-200011000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mermel LA. Prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:391–402. 10.7326/0003-4819-132-5-200003070-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rello J, Ochagavia A, Sabanes E et al. Evaluation of outcome of intravenous catheter-related infections in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1027–30. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9911093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimick JB, Pelz RK, Consunji R et al. Increased resource use associated with catheter-related bloodstream infection in the surgical intensive care unit. Arch Surg 2001;136:229–34. 10.1001/archsurg.136.2.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 1999;284:1318–22. 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donlan RM. Biofilm formation: a clinically relevant microbiologic process. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:1387–92. 10.1086/322972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffer Y, Selby NM, Taal MW et al. A meta-analysis of hemodialysis catheter locking solutions in the prevention of catheter-related infection. Am J Kidney Dis 2008;51:233–41. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yahav D, Rozen-Zvi B, Gafter-Gvili A et al. Antimicrobial lock solutions for the prevention of infections associated with intravascular catheters in patients undergoing hemodialysis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:83–93. 10.1086/588667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labriola L, Crott R, Jadoul M. Preventing haemodialysis catheter-related bacteraemia with an antimicrobial lock solution: a meta-analysis of prospective randomized trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:1666–72. 10.1093/ndt/gfm847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snaterse M, Rüger W, Scholte Op Reimer WJ et al. Antibiotic-based catheter lock solutions for prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infection: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J Hosp Infect 2010;75:1–11. 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Horo JC, Silva GL, Safdar N. Anti-infective locks for treatment of central line-associated bloodstream infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol 2011;34:415–22. 10.1159/000331262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang AY, Ivany JN, Perkovic V et al. Anticoagulant therapies for the prevention of intravascular catheters malfunction in patients undergoing haemodialysis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:2875–88. 10.1093/ndt/gft406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Arvanitis M et al. Antimicrobial lock solutions as a method to prevent central line-associated bloodstream infections: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:1741–9. 10.1093/cid/ciu671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Liu H, Deng J et al. Preventing catheter-related bacteremia with taurolidine-citrate catheter locks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Purif 2014;37:179–87. 10.1159/000360271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliveira C, Nasr A, Brindle M et al. Ethanol locks to prevent catheter-related bloodstream infections in parenteral nutrition: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2012;129:318–29. 10.1542/peds.2011-1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jansen JP, Crawford B, Bergman G et al. Bayesian meta-analysis of multiple treatment comparisons: an introduction to mixed treatment comparisons. Value Health 2008;11:956–64. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE et al. Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Stat Methods Med Res 2008;17:279–301. 10.1177/0962280207080643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP et al. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J Royal Statistical Soc (B) 2002;64:583–639. 10.1111/1467-9868.00353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brooks SP, Gelman A. General methods for monitoring convergence of iterative simulations. J Comput Graph Stat 1998;7:434–45. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2004;23:3105–24. 10.1002/sim.1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:163–71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egger M, Davery Smith G, Schneider M et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puhan MA, Schünemann HJ, Murad MH et al. A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;349:g5630 10.1136/bmj.g5630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]